Handloom skills in an industrial age

Tyabji, Laila

September, 2023

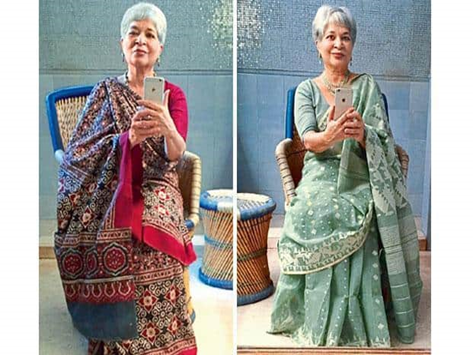

Every day for 30 days in June, Laila Tyabji took a selfie wearing a handloom sari before heading for work—she posted this series of images on Facebook.

Despite public perception, the Union textiles ministry, recently handed to Smriti Irani’s care, is hardly a comedown. It’s true that human resource development (HRD), her earlier portfolio, dictates India’s future, but textiles are a major part of our present. They encompass the lives of the largest number of people after agriculture, including some of the most marginalized and exploited: handloom weavers of course, but also mill and power-loom workers, and the labour in our garment sweatshops—often daily wagers, therefore totally unprotected by either unions or social security.

Sadly, handloom, power-loom and the big textile mills are not harmonious bedfellows. They cater to the same clientele, but have few common interests. For handlooms, power-looms are an ever-looming threat, making cloth cheaper and faster, and eating into their rural and small-town markets. For the big mills, power-loom is also the gadfly, as low production costs enable it to effectively undercut them. Nevertheless, it’s the big mills that tend to have the money and connections, and therefore the government’s ear.

In the textiles ministry, these three sectors vie with one another for concessions and attention. It’s a tussle in which handloom, very much the poor country cousin, is generally the loser. A frie...

Every day for 30 days in June, Laila Tyabji took a selfie wearing a handloom sari before heading for work—she posted this series of images on Facebook.

Despite public perception, the Union textiles ministry, recently handed to Smriti Irani’s care, is hardly a comedown. It’s true that human resource development (HRD), her earlier portfolio, dictates India’s future, but textiles are a major part of our present. They encompass the lives of the largest number of people after agriculture, including some of the most marginalized and exploited: handloom weavers of course, but also mill and power-loom workers, and the labour in our garment sweatshops—often daily wagers, therefore totally unprotected by either unions or social security.

Sadly, handloom, power-loom and the big textile mills are not harmonious bedfellows. They cater to the same clientele, but have few common interests. For handlooms, power-looms are an ever-looming threat, making cloth cheaper and faster, and eating into their rural and small-town markets. For the big mills, power-loom is also the gadfly, as low production costs enable it to effectively undercut them. Nevertheless, it’s the big mills that tend to have the money and connections, and therefore the government’s ear.

In the textiles ministry, these three sectors vie with one another for concessions and attention. It’s a tussle in which handloom, very much the poor country cousin, is generally the loser. A frie...

This is a preview. To access all the essays on the Global InCH Journal a modest subscription cost is being levied to cover costs of hosting, editing, peer reviewing etc. To subscribe, Click Here.

ALSO SEE

Chatterjee, Ashoke