With a Change of Garb, Smriti Irani Could Transform Handlooms: From Irrelevant to Dynamic

Tyabji, Laila

September, 2023

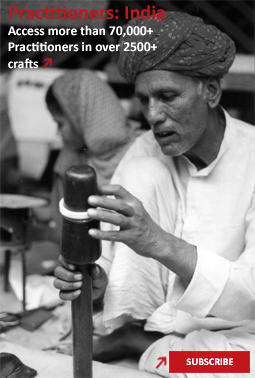

[caption id="attachment_198244" align="aligncenter" width="480"] Mohammad Ismail, a handloom weaver in Varanasi. Credit: Anandamoy/ Flickr[/caption]

Social media is full of jokes about how, in the best traditions of Indian patriarchy, Smriti Irani was found unsuited for higher education and told to go make clothes for her dolls. Other memes have her locking her textbooks in a cupboard and sitting down to weave lotus symbols on saris. The jokes reveal two deeply entrenched public perceptions: first, that managing textiles – despite being the largest employment sector after agriculture – is a demotion; second, and more surprisingly, that the textile ministry is all about handlooms and the traditional weavers that make them. This is gratifying, but ironic.

In actual fact, the handloom sector is a small embattled section of a ministry in which handlooms are totally overshadowed by the overpowering presence of the mill and powerloom sector. Their aggressive, organised and well-funded lobbies make sure that the voice and needs of the handloom weaver are completely ignored. Bureaucrats in charge of the sector change seats quite rapidly; it attracts neither eyeballs nor kickbacks. They seldom understand its complex nature. One senior bureaucrat called it a ‘sunset industry’, ignoring the fact that everywhere else in the world ‘hand-spun’, ‘hand-woven’ and ‘handmade’ have become desired designer labels. In New York,...

Mohammad Ismail, a handloom weaver in Varanasi. Credit: Anandamoy/ Flickr[/caption]

Social media is full of jokes about how, in the best traditions of Indian patriarchy, Smriti Irani was found unsuited for higher education and told to go make clothes for her dolls. Other memes have her locking her textbooks in a cupboard and sitting down to weave lotus symbols on saris. The jokes reveal two deeply entrenched public perceptions: first, that managing textiles – despite being the largest employment sector after agriculture – is a demotion; second, and more surprisingly, that the textile ministry is all about handlooms and the traditional weavers that make them. This is gratifying, but ironic.

In actual fact, the handloom sector is a small embattled section of a ministry in which handlooms are totally overshadowed by the overpowering presence of the mill and powerloom sector. Their aggressive, organised and well-funded lobbies make sure that the voice and needs of the handloom weaver are completely ignored. Bureaucrats in charge of the sector change seats quite rapidly; it attracts neither eyeballs nor kickbacks. They seldom understand its complex nature. One senior bureaucrat called it a ‘sunset industry’, ignoring the fact that everywhere else in the world ‘hand-spun’, ‘hand-woven’ and ‘handmade’ have become desired designer labels. In New York,...

Mohammad Ismail, a handloom weaver in Varanasi. Credit: Anandamoy/ Flickr[/caption]

Social media is full of jokes about how, in the best traditions of Indian patriarchy, Smriti Irani was found unsuited for higher education and told to go make clothes for her dolls. Other memes have her locking her textbooks in a cupboard and sitting down to weave lotus symbols on saris. The jokes reveal two deeply entrenched public perceptions: first, that managing textiles – despite being the largest employment sector after agriculture – is a demotion; second, and more surprisingly, that the textile ministry is all about handlooms and the traditional weavers that make them. This is gratifying, but ironic.

In actual fact, the handloom sector is a small embattled section of a ministry in which handlooms are totally overshadowed by the overpowering presence of the mill and powerloom sector. Their aggressive, organised and well-funded lobbies make sure that the voice and needs of the handloom weaver are completely ignored. Bureaucrats in charge of the sector change seats quite rapidly; it attracts neither eyeballs nor kickbacks. They seldom understand its complex nature. One senior bureaucrat called it a ‘sunset industry’, ignoring the fact that everywhere else in the world ‘hand-spun’, ‘hand-woven’ and ‘handmade’ have become desired designer labels. In New York,...

Mohammad Ismail, a handloom weaver in Varanasi. Credit: Anandamoy/ Flickr[/caption]

Social media is full of jokes about how, in the best traditions of Indian patriarchy, Smriti Irani was found unsuited for higher education and told to go make clothes for her dolls. Other memes have her locking her textbooks in a cupboard and sitting down to weave lotus symbols on saris. The jokes reveal two deeply entrenched public perceptions: first, that managing textiles – despite being the largest employment sector after agriculture – is a demotion; second, and more surprisingly, that the textile ministry is all about handlooms and the traditional weavers that make them. This is gratifying, but ironic.

In actual fact, the handloom sector is a small embattled section of a ministry in which handlooms are totally overshadowed by the overpowering presence of the mill and powerloom sector. Their aggressive, organised and well-funded lobbies make sure that the voice and needs of the handloom weaver are completely ignored. Bureaucrats in charge of the sector change seats quite rapidly; it attracts neither eyeballs nor kickbacks. They seldom understand its complex nature. One senior bureaucrat called it a ‘sunset industry’, ignoring the fact that everywhere else in the world ‘hand-spun’, ‘hand-woven’ and ‘handmade’ have become desired designer labels. In New York,...

This is a preview. To access all the essays on the Global InCH Journal a modest subscription cost is being levied to cover costs of hosting, editing, peer reviewing etc. To subscribe, Click Here.