Traditionally created for the purpose of accounting, Bhai are handbound books with yellow and white pages with hand-quilted cover. Production clusters center around Chauda Rasta in Jaipur and Udaipur. Tools such as cardboard, fabric, cotton twine, large eyed needle and sewing machine are used for the crafting process.

Balaposh or perfumed quilt is an example of exquisite artistry. It was rightfully made for the luxurious taste of Nawabs of Bengal. Today it is an endangered craft. A think layer of scented cotton is sandwiched between two layers of silk. It is an example of fine craftsmanship of Bengal crafstmen.

Balaramapuram is a small town 15 km away from Thiruvanthapuram in Kerala. These traditional products are woven with kora white cotton yarn (grey or unbleached or non-dyed yarn) of finer counts like 80's, 100's etc. The saree’s specialty lies in the preparation of the warp threads which are sized (starched) with the help of a brush. The threads become almost round in shape after sizing, giving the saree a very clear surface without any superfluous or extra fibres protruding from it.

About two hundred years ago the weaving technique practiced in a small village called Baluchar in Murshidabad district came to be known as the Baluchari. In 18th century the then Nawab of Bengal, Murshid Kuli Khan shifted his capital from Dhaka to Murshidabad. It was his patronage of the weaving tradition that led to the development of the Baluchari as a luxury textile that was favored by the elite. The magnificence of the Baluchari weave was in demand in the Mughal courts and from other royal families of the country. In the middle of the 19th century the elite in Bengal draped the Baluchari. Rabindranath Tagore's brother Abanindranath wrote that their mother wore a Baluchari on the occasion of "Maghotsava" festivities. The last known weaver of Baluchari was Dubraj Das who died in 1903 and unusually in the weaving trade several saris have been found with his signature - a sign of the high prestige associated with his skill and an exceptional example of ownership of a product among the weaving community. After his death Baluchari weaving languished and the village from which it derived its name, Baluchar, actually was submersed in water because of a deadly flooding of the Ganges. In the first half of 20th century the famous artist Subho Thakur, who was the then director of Regional Design Centre worked to revive the tradition. He invited a master weaver Akshay Kumar Das from Bishnupur, a well known centre for silk weaving, to learn the technique of jacquard weaving. Bishnupur is 110 kilometers from Kolkata and situated in Bankura district. The town is well connected with cities like Kolkata, Durgapur, Burdawan by train and bus. Akshay Kumar wove the Baluchari with the financial and moral support of Bhagwan das Sarda from the Silk Khadi Mandal. This process continued with trial and error. He was joined by Gora Chand and Khudubala a weaver couple from Bishnupur who wove the first Baluchari in Bishnupur using Akshay Kumar's design.

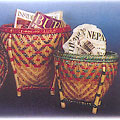

Bamboo and cane, or rattan, are considered as non-timber forest products. Products made from bamboo and rattan are popular the world over; these products have enormous earning potential and bamboo products, along with rattan-ware and reed-ware are a source of income for poor artisans who have been engaged in this craft for centuries. The stems of the giant varieties of bamboo are used for making decorative craft items. The bata or reed, a smaller variety that grows in the southern and western regions, is used for making a variety of baskets. Bamboo and bata are plant varieties whereas rattan is a creeper. Craft areas are located close to the source of the raw materials. Bamboo craft is found mainly in the south-western and central parts of the country, whereas rattan-ware is distributed all over the island-country. It is mostly women who practise these crafts, though entire families are sometimes engaged in this craft as a means of procuring a livelihood. Most of the products are made for the local market.

- Thudarena Wel: mainly found in the southern and western parts of the country

- Thambotu Wel: mainly found in the southern and western parts of the country

- Heen Wewal: mainly found in the southern and western parts of the country

- Kukulu Wewal: mainly found in the southern and western parts of the country

- Ma Wewal: mainly found in the Dry Zone

- Kaha Wewal: mainly found in the Dry Zone

- Polonnaru Wewal: mainly found in the Dry Zone

- Randing: This is one of the simplest techniques used to make a basket. The sides of the basket are shaped and filled by the use of single rattan or bamboo stakes (stiff longitudinal pieces).

- Slewing: This is similar to 'randing'. Two or three strands of the cane or bamboo stakes are used to shape and fill in the sides of the baskets.

- Pairing: This technique for weaving cane or bamboo baskets is used when a twist is given to the two softer strands which are interwoven between each pair of stakes of rattan or bamboo.

- Upsetting: This technique uses three softer strands at the start of weaving of the basket and this is continued to finish the basket.

- Waling: This term signifies the use of three softer strands for weaving which is carried out at parts of the cane or bamboo basket other than where the weaving commenced.

- Batticaloa district: Cane craft is found in the villages of Puthukudiyiruppu, Koduwamadu, Kathiraveli, Eruvil, and Panichankeny.

- Galle district (southern coast of the country): Cane work is found in the villages of Ratgama, Dodanduwa, Baddegama, Kapuwatta, Boossa, and Ahangama villages.

- Hambantota district (southernmost tip of Sri Lanka): Cane work is found in the village of Ranna.

- Kalutara district (south-western coast of the country) Bata work is found in the villages of Uduwara, Pathakada, Batugoda, Elupitiya, Polgampola, Kumbalwela, Lathpandura, Palapitiyagoda, Anguruwatota, Delgoda, Madampitiya, Badureliya, and Kaduruwela.

- Kandy district: Bata ware is found in Handessa village.

- Kurunegala district (about 130 kilometres from Colombo): Bamboo and bata work are found in the villages of Kuliyapitiya, Weeranbugedera, Pannala, and Ibagamuwa; cane work is found in the villages of Udagama and Kantholuwa in the same district.

- Matara district (southern tip of the island-country): Bata craft is found in the villages of Kitalagama, Tihagoda, Ududamana, Kohugoda, Kolatiyawela, Hakmana, Batadura, Kottegoda, and Ihala Kiyanduma; cane work is found in the villages of Elamaldeniya, Udapasgoda, Koudaowita, and Watukolakanda in the same district.

- Polonnaruwa district: Cane craft is found in the villages of Kaduruwela, Seelapura, and Raja-ela; bamboo and bata work are found in the villages of Panawala, Welhena, and Telkumuduwala in the same district.

- Puttalam district (on the western coast): Bamboo and bata artisans are found in the villages of Kalaoya and Mankulama.

- Ratnapura district (about 215 kilometres from Colombo): Bamboo and bata craftsare found in the village of Kuruvita; cane work is found in the villages of Wikiliya and Minipura in the same district.

The bamboo is a perennial grass with woody culms /stems arising from rhizomes - it has innumerable uses and a particular species may be more suited to one craft than another. Bamboo plays a significant and vital role in the life of the Nepalese and is an integral part of their life. For those of the Hindu faith it fulfils numerous ritual requirements from birth to death: rituals like the yangya performed at the sacred thread wearing ceremony and wedding ceremony cannot be accomplished without bamboo. Bamboo groves are found all over Nepal and a majority of rural households have the necessary indigenous knowledge and know-how on how to use the most suitable species of bamboo for specific purposes. The bamboo craft like many others in Nepal is faced with a declining trend due to the production and import of plastic products that are replacing a number of traditional bamboo products.

Bamboo flute is the simplest of musical instruments. Its legendary association with Lord Krishna makes it a popular Indian musical instrument. In Hindi, bamboo flute is known as bansuri which is made up of two words; baans meaning bamboo and suri that means a musical note. The Indian flute is melodious and a wide range of notes are possible by calibrating the air column in the bamboo. In Pilibhit district of Uttar Pradesh, the community of craftsmen produce bamboo flutes. It is a hereditary family enterprise. The bamboo is sourced from Silchar in Assam. The range of products includes large sized flutes for professional artists to small toy flutes. The professional flutes are made with seasoned bamboo which is carefully selected and stored. The Great musicians source their instruments from here. The large population of craftsmen produce inexpensive small flutes sold all across India. Only few master craftsmen know the secret of indexing musical notes precisely. The indexing is done through piercing the holes in to the bamboo for placement of fingers. Holes are created through red hot metal pokers and all markings are done with special scales and tools. Once the holes are pierced, there is no scope for correction. Careful calculation and precision is required while marking the holes. The craftsmen make small holes initially and then check the notes, then gradually increase the hole to required level. Indian flutes range in length from less than 12 inches (called muralis ) up to about 40 inches (shankha bansuris ). 20-inch flutes are common. Another common and similar Indian flute played in South India is the venu, which is shorter in length and has 8 finger holes (This type of Indian flute is played by the famous Carnatic Musician Shashank Subramanyam).

Bamboo mat weaving is carried out on a large scale in Kerala. This large range of painted and woven mats are in great demand all over India. The main centre for this craft is Irinjalakuda

Splits of cane and bamboo are woven to form products such as baskets, mats and musical instruments.

In Tripura, a number of handicraft items are fabricated out of bamboo mats where bamboo splits form the weft in a cotton or rayon warp. The raw material, found in abundance in the area, are the bamboo splits sold in bundles of a thousand, the length varying from 30cm to 60cm and the price depending on the width and the length of the splits. Bamboo internodes are used for preparing the splits and it is difficult to find bamboo culms with internodes longer than 60cm. It is the outer layer of the bamboo that is used for generating the splits as the inner layer is soft and fibrous. The fine bamboo splits are mainly from the Nalchar village where the craftspersons are very skilled. Fine strips are woven on hand-operated looms and joined with rayon threads in a patterned weave placed close together so that the entire screen takes on the texture and pliability of fabric. As a rule the bamboo mats are flexible only in the direction of the warp as the weft consists of the rigid bamboo splits. Coloured or textured warp is sometimes used for adding colour to the mat; the bamboo can also be dyed to enhance the mat. Several varieties of mats are used in house construction while others are used as floor coverings, for sleeping, as surfaces for drying and processing grains, as door and window screens, and as room partitions. Mats and mat articles like 'chatais' are very popular. Bamboo matting is sold by itself, the price depending on the fineness of the bamboo splits, the width of the mat, and the number of warp threads used. The products come in a variety of colours and designs and are used for interior decoration as well as for making wall hangings, flower sticks, table mats, and tray mats.

This craft is predominantly found in the Kanyakumari district. Apart from banana, other natural fibers used for weaving include sisal, aloe, screw pine and pineapple.

A common practice is to use the fruit and leaves of banana, however, in several regions of India where this natural fiber is abundantly grown, mechanisms have been developed to extract the fiber out of the banana stem which is generally said to be discarded. Minimal wastage, additional income and livelihood opportunities are thus some of the benefits achieved.

The making process starts with extraction of the banana stem, drying and converting initially into individual strands and later into ropes of varying thickness. Some of the common raw materials and tools used - Banana fiber ropes, textured rubber mat, polyester rope and water in addition to auxiliary tools - scissors, measuring tape and steel wire.

The making of the rope is extremely crucial and requires drying, peeling, soaking in water for softening of the stem before 2 to 3 strands are combined together to make one single sturdy fiber, this stage is flexible depending on the thickness of the rope required as per the design of the product. The rope can then be knitted, crocheted or woven to make products from basketry, coasters, bags, mats to textiles. Banana fiber was also once used to make pattu saris, however, the same is rarely being done now.

This craft is predominantly found in the Kanyakumari district. Apart from banana, other natural fibers used for weaving include sisal, aloe, screw pine and pineapple.

A common practice is to use the fruit and leaves of banana, however, in several regions of India where this natural fiber is abundantly grown, mechanisms have been developed to extract the fiber out of the banana stem which is generally said to be discarded. Minimal wastage, additional income and livelihood opportunities are thus some of the benefits achieved.

The making process starts with extraction of the banana stem, drying and converting initially into individual strands and later into ropes of varying thickness. Some of the common raw materials and tools used - Banana fiber ropes, textured rubber mat, polyester rope and water in addition to auxiliary tools - scissors, measuring tape and steel wire.

The making of the rope is extremely crucial and requires drying, peeling, soaking in water for softening of the stem before 2 to 3 strands are combined together to make one single sturdy fiber, this stage is flexible depending on the thickness of the rope required as per the design of the product. The rope can then be knitted, crocheted or woven to make products from basketry, coasters, bags, mats to textiles. Banana fiber was also once used to make pattu saris, however, the same is rarely being done now.

This craft is predominantly found in the Kanyakumari district. Apart from banana, other natural fibers used for weaving include sisal, aloe, screw pine and pineapple.

A common practice is to use the fruit and leaves of banana, however, in several regions of India where this natural fiber is abundantly grown, mechanisms have been developed to extract the fiber out of the banana stem which is generally said to be discarded. Minimal wastage, additional income and livelihood opportunities are thus some of the benefits achieved.

The making process starts with extraction of the banana stem, drying and converting initially into individual strands and later into ropes of varying thickness. Some of the common raw materials and tools used - Banana fiber ropes, textured rubber mat, polyester rope and water in addition to auxiliary tools - scissors, measuring tape and steel wire.

The making of the rope is extremely crucial and requires drying, peeling, soaking in water for softening of the stem before 2 to 3 strands are combined together to make one single sturdy fiber, this stage is flexible depending on the thickness of the rope required as per the design of the product. The rope can then be knitted, crocheted or woven to make products from basketry, coasters, bags, mats to textiles. Banana fiber was also once used to make pattu saris, however, the same is rarely being done now.

This craft is predominantly found in the Kanyakumari district. Apart from banana, other natural fibers used for weaving include sisal, aloe, screw pine and pineapple.

A common practice is to use the fruit and leaves of banana, however, in several regions of India where this natural fiber is abundantly grown, mechanisms have been developed to extract the fiber out of the banana stem which is generally said to be discarded. Minimal wastage, additional income and livelihood opportunities are thus some of the benefits achieved.

The making process starts with extraction of the banana stem, drying and converting initially into individual strands and later into ropes of varying thickness. Some of the common raw materials and tools used - Banana fiber ropes, textured rubber mat, polyester rope and water in addition to auxiliary tools - scissors, measuring tape and steel wire.

The making of the rope is extremely crucial and requires drying, peeling, soaking in water for softening of the stem before 2 to 3 strands are combined together to make one single sturdy fiber, this stage is flexible depending on the thickness of the rope required as per the design of the product. The rope can then be knitted, crocheted or woven to make products from basketry, coasters, bags, mats to textiles. Banana fiber was also once used to make pattu saris, however, the same is rarely being done now.

This craft is predominantly found in the Kanyakumari district. Apart from banana, other natural fibers used for weaving include sisal, aloe, screw pine and pineapple.

A common practice is to use the fruit and leaves of banana, however, in several regions of India where this natural fiber is abundantly grown, mechanisms have been developed to extract the fiber out of the banana stem which is generally said to be discarded. Minimal wastage, additional income and livelihood opportunities are thus some of the benefits achieved.

The making process starts with extraction of the banana stem, drying and converting initially into individual strands and later into ropes of varying thickness. Some of the common raw materials and tools used - Banana fiber ropes, textured rubber mat, polyester rope and water in addition to auxiliary tools - scissors, measuring tape and steel wire.

The making of the rope is extremely crucial and requires drying, peeling, soaking in water for softening of the stem before 2 to 3 strands are combined together to make one single sturdy fiber, this stage is flexible depending on the thickness of the rope required as per the design of the product. The rope can then be knitted, crocheted or woven to make products from basketry, coasters, bags, mats to textiles. Banana fiber was also once used to make pattu saris, however, the same is rarely being done now.

This craft is predominantly found in the Kanyakumari district. Apart from banana, other natural fibers used for weaving include sisal, aloe, screw pine and pineapple.

A common practice is to use the fruit and leaves of banana, however, in several regions of India where this natural fiber is abundantly grown, mechanisms have been developed to extract the fiber out of the banana stem which is generally said to be discarded. Minimal wastage, additional income and livelihood opportunities are thus some of the benefits achieved.

The making process starts with extraction of the banana stem, drying and converting initially into individual strands and later into ropes of varying thickness. Some of the common raw materials and tools used - Banana fiber ropes, textured rubber mat, polyester rope and water in addition to auxiliary tools - scissors, measuring tape and steel wire.

The making of the rope is extremely crucial and requires drying, peeling, soaking in water for softening of the stem before 2 to 3 strands are combined together to make one single sturdy fiber, this stage is flexible depending on the thickness of the rope required as per the design of the product. The rope can then be knitted, crocheted or woven to make products from basketry, coasters, bags, mats to textiles. Banana fiber was also once used to make pattu saris, however, the same is rarely being done now.

Banaras Brocade Sarees are made of finely woven silk and decorated with intricate designs using zari; this ornamentation is what makes the sarees heavy. Their special characteristics are Mughal-inspired designs/elements such as intricate floral and foliate motifs, such as kalga and bel. Other features are gold work, compact weaving, figures with small details, metallic visual effects, “jali” (a net-like pattern) and “meena” work. These are woven on the conventional Banaras handloom jacquard, sometimes with “jala”, “pagia” and “naka” attachments for the creation of motifs.