A Kachchh shawl is a traditional shawl woven in the Kutch region of the Gujarat, India. These are largely woven with Kachchhi motifs in Bhujodi village of Kutch. Traditionally Kachchhi weavers belong to Marwada and Maheswari communities. Kachchhi shawls have received geographical indication tag under the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999.

Kalamkari hand painting is done by only one family in Sickinaikenpet in the Thanjavur district. It is done with a stick which is wound with thread that has been dipped in dye. A hereditary profession, the family belongs to a long line of Kalamkari artists who move to Tamil Nadu from Andhra Pradesh. Kalamkari paintings form temple hangings, panels, doorframes and tubular hangings (thombais) with scenes from the Puraanas and other great epics. The temple hangings are called vasamalai. The technique used to paint them is similar to that at Sri Kalahasti but the characterisation is religious rather than folk. Vegetable dyes are used and the colours are very bright and dramatic. Geometrical and floral patterns are found in the borders and backgrounds. One of the items made here is the Kuralam which is a decorative cloth to hang on either side of the chariot during the procession. Elaborate woolen cut work is done as ornamentation; this is usually given by devotees as votive offerings. Saris, linen and furnishing material are also hand painted here in dramatic geometric patterns.

Kalamkari hand-painting on fabric is a technique used to embellish temple cloth and hangings. Painted hangings are used for religious instruction, in temples, and for draping behind the idol in temple cars during processions. The process followed here is even more painstaking than the kalamkari done at Masulipatnam as the entire design is drawn bv hand using a kalam or pen made from wood (tamarind twigs charred to charcoal sticks) and fibre. All the processes are nearly the same as at Masulipatnam except for the absence of blocks. This craft grew mainly around places of pilgrimage and one of the leading centre is Sri Kalahasti in Andhra Pradesh. The temple hangings and tapestries from Kalahasti are famous worldwide. Madder and indigo processes are used here and alum is the mordant used to fix the colours. Vegetable dyes in deep rich shades red and blue are used, while green is obtained as a combination of yellow and blue. The washing of the cloth to remove starch and the washing between dyeing and bleaching is done from flowing water in a stream or river. The lines of the design are drawn with a mixture of iron-filings and molasses. The colour schemes used are traditional ones, with women figures in yellow, gods in blue, and demons in red and green. The background colours are usually red with motifs of lotus and other flowers. The aesthetic quality of fine kalamkaris derives from the superb conceptual and technical skill involved in the work. Religious themes dominate, with temples, epics, and mythological figures being depicted frequently. The stories illustrated on these panels are from Puranic legends and from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Paintings are usually done in cloth panels which narrate entire stories, with the smaller ones depicting important religious events like Sita's marriage. As all the panels are done by hand, and each one is unique; no two panels will look the same. A panel may include a story-theme written in verse under it to explain it.

These are miniature folk paintings; there is a great proficiency in line drawings shown here. The drawings are made on flat, hand-made coarse paper, a little larger than a foolscap sheet. The first outlines are very clearly made in single, bold strokes with a brush. The themes are caricatures and satirical sketches dealing with everyday events and/or happenings at the law courts, bazaars, and the like. Popular sayings and proverbs are also well illustrated. The painters or illustrators are called 'patuas'. The paintings are a symbol of revolt against the oppressive socio-economic system. They, thus, reflect radical realism and profound truthfulness. Street-scenes, popular announcements, festivals, family reunions, joys and sorrows are depicted in the paintings along with biting satires on the vices of a decaying social order. Drunkenness, prostitution, domestic quarrels, and the like are shown with playful satire leading to a macabre climax. The paintings have well-sustained rhythms of spatial relations and bold colouring. The popularity of these paintings were taken advantage of and German lithograph imitations on glazed paper, at cheap prices, flooded the market. This resulted in the demise of this art form --- the last representatives of the Kalighat tradition are no more.

The kamangars are a community of carpenters, designers, housebuilders and craftspeople who are responsible for crafting the magnificent wall paintings in Gujarat. The kamangari paintings have been flourishing since the rule of Lakhaji II. The kamanagars were commissioned to paint homes, places of worship and administrative buildings and adorn these buildings with their skill. The themes range from mythological to natural motifs and daily life. The kamanagari craft is practiced on adding ornamental and cultural value on wall murals and other interior elements. [gallery ids="177993,177994,177995"]

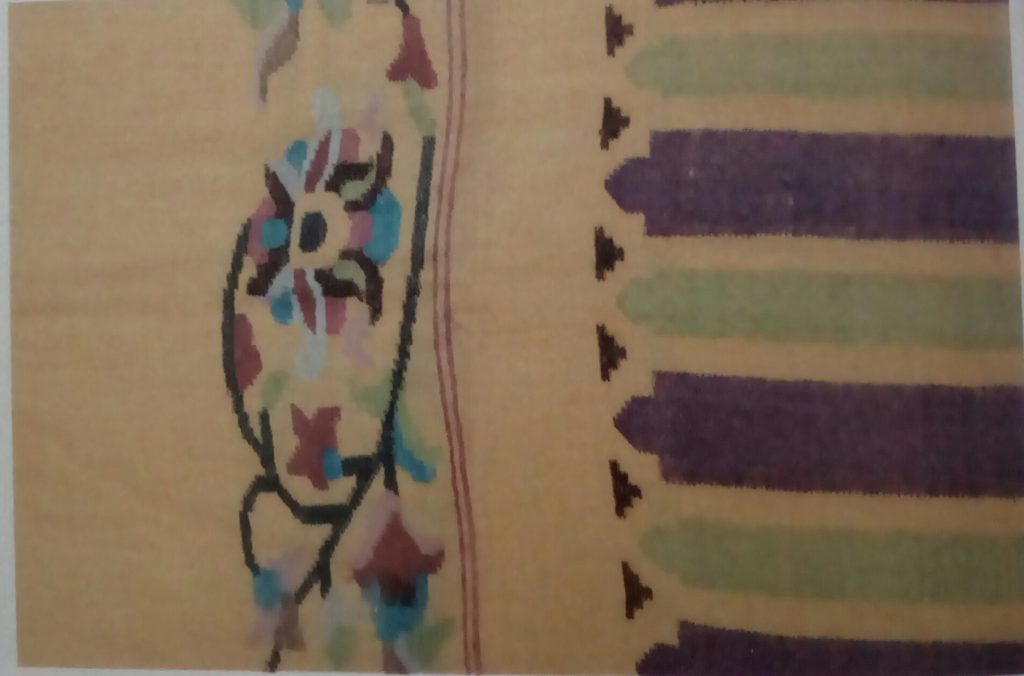

Kanchipuram is the famous weaving centre in Tamil Nadu. The weaving community in Kanchipuram is called Salgars (from the Sanskrit word, salika meaning weaver), and they claim descent from Sage Markanda, the weaver of the gods. Earlier the design-jacquards were made from round lamp-wicks but now mechanised hooks and jacquard boxes are used. The designs on the body of the sari are woven with gold thread and the motifs range from figures to temple gopuras (towers) along the border. One of the traditions of the Kanchipuram saris is the contrasting borders. Two weavers work on three shuttles to make the sari; the pallu is also done separately, especially if it is of another shade. The meeting of the body of the sari with the border is characterised by a zigzag design, the vanki design, which can also be found all over the body. Typical motifs used in these saris are the sun, moon, chariots, swans, peacocks, parrots, lions, coins, mangoes and leaves. Patterns are also formed by lines and squares and when the jasmine motif is found either inside a square or scattered all over, it is called mallinaggu. The Thandavalam motif has parallel-line motifs running all over the body of the sari. In the pattu motif, the pallu and the border alone have floral motifs independently woven on them. Other motifs used are creepers, peacocks and the rudraksh or red-dented seed pattern on the body and end-borders of the sari. These saris are usually made in brilliant reds, saffron, orange, emerald, henna green, maroon, peacock blue and ochre with bright contrasting borders. These days silver is being used in addition to gold. Weavers also make tissue saris, using only gold or silver metal threads. This tradition of silk sari weaving at Kanchipuram arose out of temple-traditions with the famous Kamakshi temple situated there. Upper-caste families wore only silk and weddings and festivals (Deepavali, Pongal, etc) were an occasion for the purchase of many silk saris.

Kangra Paintings have no specific dimension. They are painted in small as well as in big sizes on walls, cloth or paper. Rectangular paintings, generally 12 x 16 inches in size, are very popular on fibre paper. A major theme of Kangra Paintings is love. The painters’ favourite text is the Rasikapriyaby the poet Keshav Das, which derives inspiration from the Krishna cult. The Nayak and Nayika in the Rasikapriya are Krishna and Radha, the ideal lovers symbolizing God and the Soul. All great art is inspired by religion. The paintings and sculpture of Ajanta and the great monuments of Borobudur in Java were inspired by Buddhism, while Christianity influenced the paintings in medieval Italy and Spain. Thus, Kangra art is the visual expression of a cultural movement which had its roots in a great spiritual upsurge. Kangra Painting is not a sudden development unrelated to the life of northern India, but is the culmination of the spiritual and literary revival of Hinduism.

Kanpur has been a very prominent hub since ages, for the production and manufacture of leather saddlery. The craft of taming vegetable tanned leather and making harnesses and saddlery gained popularity during the colonial rule in Kanpur and other neighbouring towns of Uttar Pradesh. The manufacture of horse-riding and driving equipment and products come under the banner of small industries. The saddlery is crafted with great skill to maintain the tensile strength of the leather, so that it is both flexible and durable. The top parts of the items are made with leather to provide comfort while riding. Today, Kanpur is the sole independent centre of production, supplying global markets as well. Besides Kanpur, materials are also procured from Phillaur, Jalandhar and Meerut.

Kans or kayen is the local name of an alloy of two metals - copper and tin - that is used in making dishes called dakayen. The kans metal alloys are used in making domestic utensils - such as bowls and cooking utensils - and utilitarian items such as lamp stands by the process of metal casting. Dishes hand-crafted by hammering and heating were traditionally an integral part of every household; there is reason to believe that the forging of these kans plates is a unique centuries-old technique. However, with the introduction of stainless steel tableware in recent times, these traditional kans metal dishes are gradually disappearing from most households.

Kantha embroidery was done by village women on soft, discarded dhotis and saris. Layers of old white dhotis or white or faded saris were held together and stitched with running stitches along the edges using thread drawn out of the faded borders of the saris. The borders were torn and kept aside especially for this purpose. If the kantha was a quilt then five to six layers of soft fine cloth were used. For other purposes three or four layers were used. The top and bottom layers of a kantha are always white or of a very light colour so that the embroidery is visible. The muted colours gave the kantha a soft pastel effect. Those used as quilts are called lepkanthas and those made as counterpanes are called as sujanikanthas. Kanthas are also made as covers for boxes and mirrors, as pillow cases, stoles for women, and shawls for men. The stitches are patterned running stitches which cover the entire surface of the piece. The layers are held by the stitches and the surface gets a delicate, rippled look. The designs are never repeated. Traditionally kanthas were never meant for sale --- they were either gifts or else made for personal use. Kantha patterns include geometrical or floral motifs and themes drawn from the living world with a central design which is usually floral. Traditional designs are copied to make kanthas in the form of saris, stoles, table linen, and furnishing fabrics. New cotton and silk are used for these and except for saris, the items are layered. Now kantha saris and dupattas have become fashion items with the fabrics used ranging from silks to cotton. Also see, 'The Lotus and the Kantha'.

Kantha embroidery was done by village women on soft, discarded dhotis and saris. Layers of old white dhotis or white or faded saris were held together and stitched with running stitches along the edges using thread drawn out of the faded borders of the saris. The borders were torn and kept aside especially for this purpose. If the kantha was a quilt then five to six layers of soft fine cloth were used. For other purposes three or four layers were used. The top and bottom layers of a kantha are always white or of a very light colour so that the embroidery is visible. The muted colours gave the kantha a soft pastel effect. Those used as quilts are called lepkanthas and those made as counterpanes are called as sujanikanthas. Kanthas are also made as covers for boxes and mirrors, as pillow cases, stoles for women, and shawls for men. The stitches are patterned running stitches which cover the entire surface of the piece. The layers are held by the stitches and the surface gets a delicate, rippled look. The designs are never repeated. Traditionally kanthas were never meant for sale --- they were either gifts or else made for personal use. Kantha patterns include geometrical or floral motifs and themes drawn from the living world with a central design which is usually floral. Traditional designs are copied to make kanthas in the form of saris, stoles, table linen, and furnishing fabrics. New cotton and silk are used for these and except for saris, the items are layered. Now kantha saris and dupattas have become fashion items with the fabrics used ranging from silks to cotton. Also see, 'The Lotus and the Kantha'.

The Karvath Kati sarees a symbol of celebration and prosperity originates from the Vidharbha region of Maharashtra. Worn at auspicious rituals and at weddings they are also traditionally worn by the Vidharbha bride. This traditional saree is called Karvat Kati due to its unique saw-edged pattern on the border. The bodice of the sari also contains designs resembling the saw teeth pattern. The weavers have adapted these designs from the sculptures seen at the famous Ramtek temple in the region. Hence, besides its cultural significance, the motifs and patterns make the garment auspicious in itself. These sarees are handcrafted using tussar silk which is sourced from Vidharbha, Nagpur, Bhandara and Gondia regions. They are woven on pit looms using three fly shuttles of different colored yarns and are a testament of the mastery of weavers. Today, the weavers of the Karvat Kati pattern have expanded their repertoire beyond sarees to include shirting, dress materials and dupattas.

The Balaramapuram sari woven in Thiruvananthapuram district follows a tradition that is about 150 years old. The pit-loom is used for weaving and the yarn count is 100 for the warp and weft. Pure zari is used for border designs. Fine counts up to 120 are crafted. The plain white Karaikudi saris have a woven gold band on the borders and the pallu.

Bangladesh is well known for its differing styles of embroidery. Dhaka, in particular, was renowned for its kashida work, made with muga silk thread, chikan embroidery on muslin, and zardozi, a combination of silk and gold embroidery. An embroidered textile has a matchless splendour of its own. It merges the striking quality of jewellery with the vibrant elegance of many-coloured stitches. Although the earliest surviving embroideries date from the sixteenth century, the proficient practice of this art probably dates back several centuries, as is proven by the discovery of copper needles and figurines draped in embroidered garments at Mohenjo Daro. Unlike many other crafts it is essentially a feminine production, requiring skill and sensibility rather than physical strength. Inspiration for this art is drawn from the myriad sources of nature, history, legends and religious beliefs, which give it limitless flexibility and freedom of interpretation.

Kasuti embroidery is a special craft practised mainly in Uttara Kanara district or North Kanara district. Its secret lies in the fact that it can be done only by counting the threads of the weft and the warp. There is no possibility of tracing or implanting the design prematurely as outlines. With considerable dexterity, an ordinary sewing needle is used to create a variety of designs with coloured threads on the cloth. The embroidery is done only by women. The two kinds of stitching are gavanti (line or double running stitch) and murgi (zig-zag lines done with a darning stitch). The two sides are neat and identical. Negi is the ordinary running stitch used in large designs, creating a woven design effect. Menthi is a cross-stitch used for architectural patterns. This embroidery is done mainly on handloom irkal saris.The motifs here range from architectural designs to a cradle and from an elephant to a squirrel. The main motifs are religious and are found to be larger near the pall; as they move downwards in a sari the motifs get smaller and smaller. Vertical, horizontal, and diagonal stitches are used. The motifs have to be completed as the stitching line comes back to fill in the blank spaces. Coorg has its own embroidery which is like Kasuti. In this the cross-stitch and the line or double running stitches are combined. The motifs are religious or taken from everyday life.

Kathakali dance form of Kerala is a colourful dance drama and one of the seven classical dances of India. The word kathakali literally means story-play. This dance form is noted for the elaborate make up, detailed face gestures, attractive costumes and well defined body movements. In Tradition, Kathakali represents the narratives of the exploits of various deities and demons. The main center for production of the accessories is Payyanur in Kannur district:

The dance of Kathakali has the most outstanding head-gears known as kiritams, produced on a large scale to suggest the supernatural powers of the character. The inner portion of kiritam is made of cane to ensure a good fit, and the body is carved from a durable kumizhi wood. The wood is hard and does not chip easily. It also ensures long life of the headgear and allows intricate detailing thus making it ideal for making head gears. The kiritam and other wooden ornaments worn by the performers are intricately carved with glass, stones, gold and silver foils, bead and peacock feathers. These are designed as per the qualities of the dancers: pacha (green) is benevolent and noble; kathi (knife) symbolises evil and demon-like characters. Each of the head-gears have two types of coronets, of two superimposed domes ending in a bud-shaped finial, a large circular disc behind it, and a halo between the coronet and the disc. It is carved out of wood and from the hollow bottom up to the top of the first dome, every row is decorated with closely knit silver beads on a red scarlet base and beetles' wings set vertically in parallel rows. Glass pieces fixed on aluminium foils, large glass flower petals, and small silver beads are in the centre. Ornamental silver fringes are above the peacock shape made of green glass pieces, between the top of the second dome and the finial. The top of the dome has concentric circles with the rows of decoration repeated. The disc is like a perfect piece of jewellery, is picturesque on both sides, and has a circular row of vines of golden stems and leaves, green buds, grapes with peacock feather stems, and a golden circle of foils converging on a round piece of glass in the centre. The appearance of the convex shaped rising circle of vines is like a fully blossomed flower.

The players who come in the next category have beards of three colours: red, white, and black. Red bearded characters are vicious and vile, white bearded characters are strong, gentle, devoted, and loyal (like Hanuman), and black bearded characters are the destroyers (like Kali), and include hunters and the like. The characters with the red and black beards have large head-gears with decorations more or less similar to the previous headgear. There are some differences: the edge of the disc is decorated with woollen tufts, their colour is same as that of the beard, the base of the peacock stem is rolled into oval shaped flowers, and in place of the vines, grapes are fixed on the disc. Hanuman's head-gear is like a Chinese hat with two domes, ending in a bud-like finial, adorned with tassels. The rest of the frame is in cane and the outer surface is covered by white flannel while the bottom with is covered in scarlet and has four lines of silver ornamental fringes suspended in concentric circles and a silver crescent. Long artificial locks also float down.

The head-gear of sages or rishis consist of two domes, the lower being larger. The usual adornments are there along with twisted coils and, in addition, there is a rudrakshamala (rosary of several faceted seeds) encircling the dome. The hunter's head-gear resembles an expanding lotus, the cane frame rising from the bottom, covering almost half the height. This is covered with a dark cloth which is decorated with silver petals resembling the screw-pine blossoms.

Krishna has a special head-gear of a conical hemispherical dome with a woollen garland of different colours encircling its tip. Over this are fixed the eyes of peacock feathers to create the form of an expanding lotus. There is has a margin of oval shaped flowers formed by peacock feathers. An oval piece of blue or black ornamented cloth hangs behind the coronet and forms a beautiful cover.

The folk dance of Malabar, Theyyam literally means 'the dance of gods'. Rooted in the indigenous animistic religious beliefs, this performing art tradition relies on narratives that are elaborated through a combination of singing, chanting and dancing. Each character in the narrative is a representation of a deity; the costume and appearance of the character follow ritualistic prescriptions that have been followed for years. A three dimensional sculpture in motion, the entire costume shows the influence of the region's sculptural art forms. Lightweight materials such as the wood from the areca nut palm and bamboo are used in the construction of the frame of the most significant accessory, the mudi, headgear, as well as for the lower garments. Coconut tree wood and areca nut palm wood are used to make ornaments. Areca nut wood is also used for making marmula, breastplates, for female performers and the masks generally worn by those characters considered fierce. The Theyyammudi, headgear, is heavily ornamented, but lighter in weight, as it is made from the wood of areca nut palm and bamboo. Tools are uli/ chisels; vallamitti / flat chisels; arani / files; alavattu / marking tool; compass and bow drill

A unique craft of Manipur is the double-weave mat known as the kaunaphak reed mat. Known as phak in Meithei, a Manipuri tribal language, the reed used to weave the mat is called kauna. The mat is made by the local people for their own use, as well as for commercial purposes. Phak is yellow in colour and is the succulent stem of a plant that grows in water. Reeds are carefully chosen for the mats. The plant is cut only when it has reached maturity. Once cut, the stems are dried and become soft and pithy and quite brittle. A bunch of cut stems of the appropriate length are then woven with bamboo placed at suitable distances to give the mat its desired length. The border has an interesting pattern and is about an inch wide. The kauna reed mats are not meant to be washed for the reed spoils with moisture.