Gabbas are the colourful rugs crafted out of old woollen blankets and lois. The old blanket pieces are dyed in colours and attached together with a cotton backing. These joined pieces are then embroidered with vividly coloured geometric and floral patterns. Gabba is fashioned in various shapes and sizes unlike the regular rugs monotonously shaped in rectangular shape with a medallion or motif in the centre. An inexpensive and brightly coloured rug can be seen in every house in Kashmir. It is an effective floor covering and sometimes used as a mattress in cold areas of the state. The popular production clusters are Anantnag and Srinagar district in Kashmir. The craft crossed the state boundary when the carpet weavers were once invited to Punjab to prepare shamianas, qanat and gabbas. With simple tools like ari- hooked needle and scissors the rugs converted to Gabba give an accented touch to the floors. The gabbas can be either appliquéd or embroidered. There are no limits to inspiration for the embroiderer since Kashmir is a paradise on earth with nature playing abundantly. All the motifs are derived from the nature and the scenic environment around the state.

Gadwal in Andhra Pradesh is known for weaving saris in cotton weft, with richly brocaded gold borders and pallus with elaborate designs. These saris were originally woven for the royalty and the nobility. The borders and body of the sari are traditionally in dramatic colours.

According to Lynton, 'it is believed that the brocading ability of many of the weavers in the Gadwal originate from Banras, where a local maharaja sent their ancestors to learn brocade-weaving skills'. However, the designs 'do not show any Banaras influence' but are instead 'strongly south-east Indian in structure and aesthetic quality' (Lynton: p. 104).

The Gadwal saris show links with the Konrad saris of south India.

The Konrad

|

Gadwals are traditionally woven in the interlocked-weft technique (kupadam/tippadamu).

The field is usually often of unbleached cotton. Some coloured cotton or silk checks can be found in the field. However, a completely silk version, usually in bold contrasting colours is also made.

The silk borders used either tasar silk or mulberry silk. The Gadwals have the kumbham (triangular motif in sari borders; also auspicious) in the borders and are thus also known as kumbham or kupadam saris.

The end-piece of the Gadwal sari is distinct. They usually carry an inverse temple motif known as reku in the end-piece.

Knotted, woollen pile carpets have probably been produced in the most northern areas of Nepal for centuries. It is believed that the tradition was introduced from Tibet where it was an ancient craft - under the King Song-tsen Gompa (AD 620-49) It is believed that if the Tibetans were producing such carpets at that time, it is conceivable that the practice was taken up in areas that are now part of Nepal although this proposition remains speculative. A saddle-carpet appearing in a Nepalese mandala painting of 1564 demonstrates that they were certainly known in Nepal over 400 years ago. The people of northern Nepal today use the carpets mainly as seat-pads, beds, and saddle-blankets. They may occasionally also be used as door curtains and pillar wraps. Much more substantial production of carpets has occurred since. The equipment needed to establish such an enterprise was relatively cheap to make and operate, and this also enabled many individual home weavers, Tibetan immigrants, and Nepalis of various ethnic groups, to start working for a contractor or a small family business.

-

One or more metal gauge rods - depending on how many weavers are working on the carpet as the pile length (average = 1.25 cm) is determined by the diameter of the rod

- A cutting tool or knife to cut the loops on the gauge rod

- A comb beater (panja) to beat down the weft

- A mallet (twaga) to beat down the rod with the weft

- A shuttle for the warp yarn

- A pair of scissors for trimming

- Wooden wedges, which can be pushed between the pegs and the warp beam if the tension needs adjusting

Once a flourishing craft the knotted wool carpets of Amritsar are faced by a declining trend with few craftspeople left plying their trade. Competition from machine made carpets and other wool carpet centers has resulted in a slow but steady decline in this craft. Weavers can be found in Konke Village, Tapiyala village, Chugawan village, Lopoke village, Raja Sansi and KotKhalsa around Amritsar. Originating in the early 19th century, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh the erstwhile King who brought Kashmir under his rule had many Kashmiri carpet and shawl weavers migrate to Amritsar under his patronage. This patronage combined with the availability of fine quality wool from the neighbouring hill states ensured the creation of exceptionally fine hand-knotted wool carpets. Uusing the Persian knot technique the carpet weavers would wind the wool around the individual threads of the cotton warp. Inspired by Persian and Bokhara techniques the weavers used a color coded naksha pattern drawn on a graph, while weaving new designs. With the decline in the craft there are no naksha pattern makers left in the villages around Amritsar. Today the clientele is mainly export houses who provide the naksha patterns. The business is handled by middlemen and the weavers' earnings are paltry.

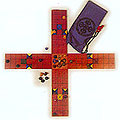

The pachisa game is a combination of Ludo and Shatranj, the Indian chess game played as long ago as the time of the great Hindu epic Mahabharata. The pachisa game played on a five piece painted wooden board with four sides and a center. This game has received a boost with its popularity among the tourists and is now crafted and sold in many gift stores in Katmandu Valley.

Nepal's national board game is bagh chal, literally 'move the tigers' (bagh = tiger; chal = move). This is a fascinating and engrossing game requiring concentration and skill. The game is played on a lined board with 25 intersecting points and requires two players. One player has four tigers, the other has 20 goats - the aim is for the 'tiger player' to 'eat' five goats by jumping over them before the 'goat player' can encircle a single tiger and prevent it moving.

Gamthi is a style of block printing that takes us back to the medieval ages of India. 'Gaam' means village and 'Gamthi' refers to the act of origination of this art from the villages of Gujarat and Rajasthan. Long before western dyes were available to the indigenous villagers, parts of plants and rocks and metals would be used to create over 27 different types of colours. This type of Block Printing was originally used for the purpose of decoration of accessories. Dupattas and chunaris and turbans would be adorned with these prints and be known as Saudagari prints. These prints would usually have a repetitive motif that is used throughout the fabric.

The double-coloured Ganga-Jamuna saris are traditional Maharashtrian saris. The main characteristic of this sari is the plain weaving with solid colours on either side --- both sides of the sari can thus be worn. This sari is woven on double cloth principle with two shades of colour in the warp and weft.

Originally made by kneading the ashes from Holika fire and mud, Gangaur idol making venerates the Goddess Gangaur. However, these composition of these idols has been replaced by wood and clay modeled to resemble the worshipper by artists of the Matheran and Usta communities. Production clusters are centered around Bikaner. Tools such as chisels and carving tools are used for the carving process.

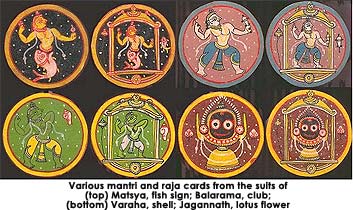

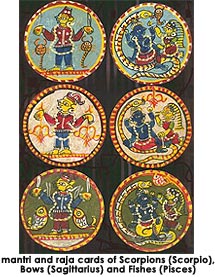

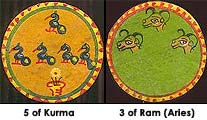

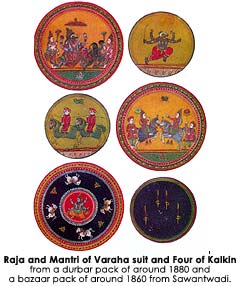

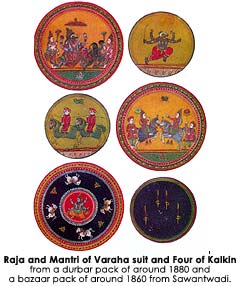

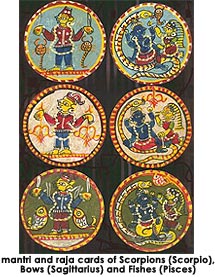

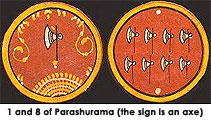

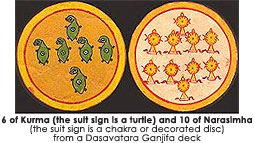

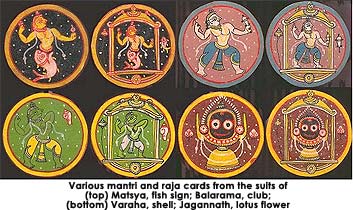

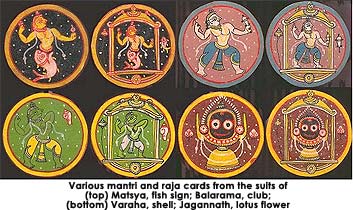

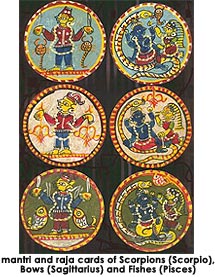

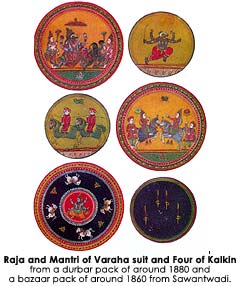

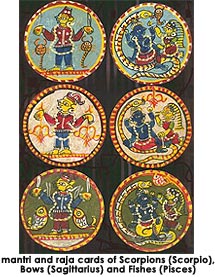

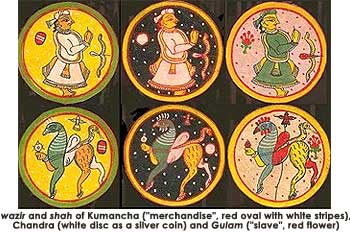

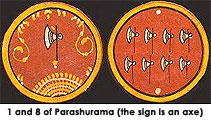

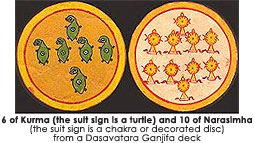

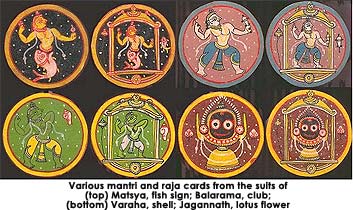

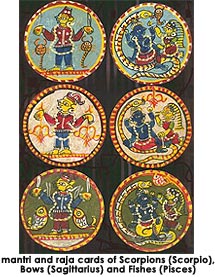

Games are a common passion, a common pastime which cross all sections of the community. Playing or watching games form a highly significant aspect of culture, both because of their importance in peoples lives and their capacity to bring families and communities together and because of the degree of creativity and skill that go into devising them. No indoor games match the passion with which cards are played in India. One such card game, now facing extinction is Ganjifa The leading theory is that the Ganjifa pattern was created in Persia, most likely under the influence of playing cards from the East (probably money-suited decks), and introduced in India by the Mughals. The origin of the term Ganjifa is obscure. Ganj is a Persian term meaning 'treasure, treasury or hoard'. The first mention of the game is made in the Babarnama, the memoir of Babar. The founder of the Mughal dynasty, Emperor Babur, who ruled from 1526 to 1530, reports in his annals, "This evening... Mir Ali Korchi was dispatched to Tatta [in Sindh] to Shah Hussain. He is fond of the game with cards and had requested some which I have duly sent him." The Ganjifa are made in Bishnupur, Bankura district of West Bengal. These are very similar to the Ganjappa cards of Orissa. The cards have, painted on them, images and symbols representing the ten incarnations of Lord Vishnu, the Dashavatar. Apart from this, the ten rupas or forms of the Mother Goddess, Sati; or Dasa Mahavidya may also be illustrated on these cards. However today these cards are primarily made on specific orders, hence the illustrations may change to meet the demand. Under the royal patronage of the Malla dynasty of Bishnupur, this game had become famous. It is believed that the designs of the cards have not changed in the slightest in the last one thousand years. Dashavatar taas are made in packs of eight or twelve suits. What was once a popular game is now archaic and valued more as an antique. The Dashavatara taas generally consists of 120 cards instead of 96 of the Mughal set, and in Bishnupur unlike the other States it is played by five players. The names of the suits of this Dasavatara ganjifa are Matsya (fish), Kurma (turtle), Baraha (boar), Nrisingha (a combination of man and lion), Baman (Brahmin dwarf), Parasuram (the sixth incarnation with axe), Sri Ram (the hero of Ramayana), Balaram (brother of lord Sri Krishna), Lord Buddha (the ninth incarnation with absolute peace) and Kalki (the 'abatar' yet to come Every suit of a Dasavatara pack consists of 12 cards each with a Raja as a king or an upper court card and a Mantri as a minister or a lower court card along with ten general numeral cards. These suits can be identified by their symbols. The Matsya suit symbolized by a fish, Kurma by a turtle, Baraha by a shell, Nrisingha by a chakra or disc, Baman by a water pot, Parasuram with an axe, Sri Ram with an arrow or a bow and arrow or a monkey, Balaram with a plough or club or cow, Lord Buddha with a lotus and Kalki with sword or horse or a parasol. The rules of play of Dashavatara ganjifa is essentially the same as the Mughal ganjifa except that the Dashavatara ganjifa has eight suits while the Mughal ganjifa has ten suits. Besides the Dashabatar pack Bishnupur is also known for its Naqsh Taas popular with its stylized patterns and shapes. The Naqsh taas pack consist of 48 cards with 4 equal suits of 12 cards each. These cards are generally produced in two different sets-one large and the other a miniature deck of 2? of diameter. These miniatures are created with detailed and minute attention and precision. Additionally the box containg the cards is equally detailed and elaborate in design and patterning. The Naqsh Taas is a gamblers game and was played at Janmastami and during the auspicious time between Dussera and Diwali and at Kali Puja The process of making the cards is laborious and involves almost all the members of a family to make a a single set. The Bishnupur Dashabatar Taas are made from old cloth pieces pasted one on top the other tamarind glue which are layered and pasted. After pasting layers after layers the stiffened piece of cloth is stretched, dried and cut into cloth roundels, which are 4-5 inches in diameter. Once they are dry, the designs are painted on white backgrounds with the artist painting on the details of figure cards and the numeral cards. . The back is left plain and unpainted. Due to the increase in the price of natural colours, the cfatspersons now prefer to use water colours With the introduction of European printed cards in 19th century the play with the Dashabatar Taas declined. Now the cards are created not for players but for tourists and art-lovers. With the decreasing demand and the lack of interest and awareness the Dashabatar Taas their art and the play is in need of urgent safe guarding with only the Fouzdar family of Bishnupur still engaged in creating the traditional Dashabatar ganjifa and Naqsh taas

Games are a common passion, a common pastime which cross all sections of the community. Playing or watching games form a highly significant aspect of culture, both because of their importance in peoples lives and their capacity to bring families and communities together and because of the degree of creativity and skill that go into devising them. No indoor games match the passion with which cards are played in India. One such card game, now facing extinction is Ganjifa.

The next, more detailed, reference is found in the Ain-I-Akbari, a book written by Abul Fazl Allami towards the end of the 16th century during the reign of the great Mughal emperor Akbar (1542-1605). Abul Fazl devotes a short chapter to the games - chess and ganjifa - played by Akbar.

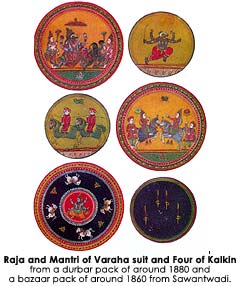

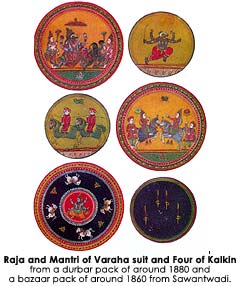

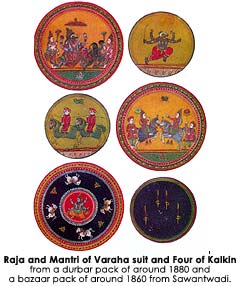

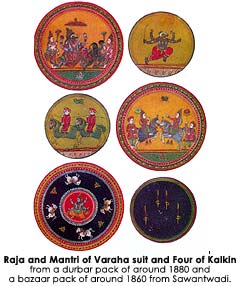

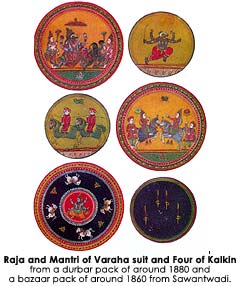

Card playing became very popular and widespread in the 17th and 18th century at the innumerable Indian courts, especially within the zenanas (women's quarters) where Ganjifa was the recourse from institutional boredom. With rising popularity it became the subject of much writing and beautiful decks were created for the nobility made of ivory or tortoise shell inlaid with precious stones (called darbar kalam). But the game was so popular it spread among the common people, who used cheaper sets made from wood, palm leaf, pasteboard, and various other inexpensive materials (called bazaar kalam).

The game spread with the expansion of the Mughal Empire. The Deccan belt, with its intermingling of North and South, Hindu and Muslim cultures became fertile ground for the development of a variety of games and cards. The hinduization of Ganjifa cards contributed to their spread and popularity and was played in Rajasthan, Bengal, Nepal, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Karnataka.

The practice and the rules of the game, played for centuries in India - across palaces and hovels - is now almost wiped out replaced, we hope not irrevocably, by the western import of the 52 set game. These cards, now curiosity items for tourist, are still hand-made and hand-painted by skilled craftsmen (chitrakara). Therefore, each deck is a truly unique item.

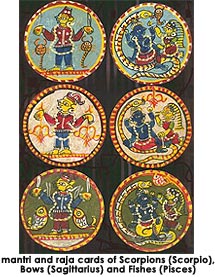

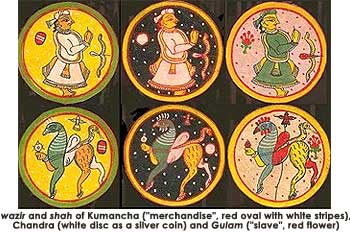

The pips are small suit signs, more or less stylized, arranged in patterns of various fashion, a free choice of the artist who painted the deck, though often influenced by the regional trend.

The illustrations depict human figures and incarnations of many Indian divinities, posing in different attitudes, that change in accordance with the pattern of the deck and with the regional custom. Ganjifa packs that come from the same area not only have similar illustrations but matching backgrounds too, differing from those of decks made elsewhere. The use of different background colors for identifying the suits of the deck was once found also in the other variety of traditional Persian cards, the As-Nas, now extinct. The geographic origin of a deck affects its background colors, one different for each suit, thus alternative names for Ganjifa decks, according to how many suits they have, are atharangi ("eight colours"), navarangi ("nine colours"), dasarangi ("ten colours"), baraharangi ("twelve colours"), and so on. In patterns with more than eight suits, some colors may appear similar, but in this case the rim, clearly different, provides an easy reference.

The geographic origin of a deck affects its background colors, one different for each suit, thus alternative names for Ganjifa decks, according to how many suits they have, are atharangi ("eight colours"), navarangi ("nine colours"), dasarangi ("ten colours"), baraharangi ("twelve colours"), and so on. In patterns with more than eight suits, some colors may appear similar, but in this case the rim, clearly different, provides an easy reference.

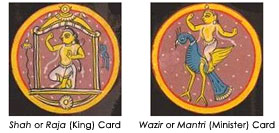

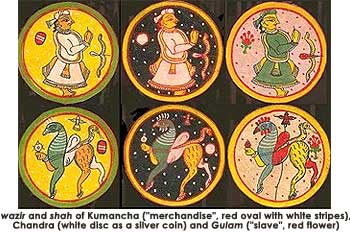

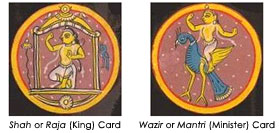

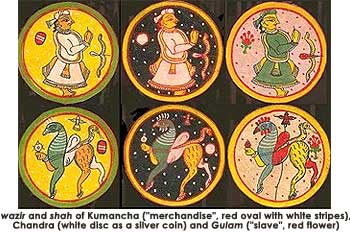

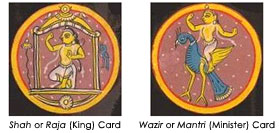

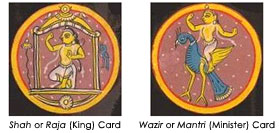

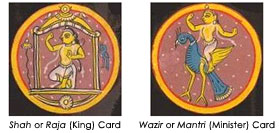

It has 96 cards divided into eight suits. The court cards are usually referred to with their old names: wazir (the minister), while the king is called shah (also padishah, or mir, probably short for amir).

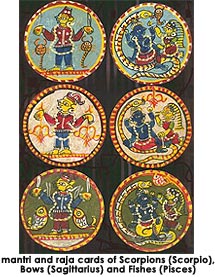

In most parts of India, the wazir and shah subjects feature human figures (the king either seated on a throne or under a canopy, the minister often mounted, with or without his retinue). But in decks made in Odisha they are replaced by characters of the local mythology and religion.

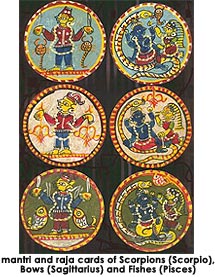

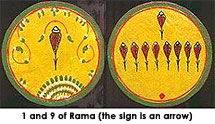

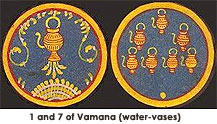

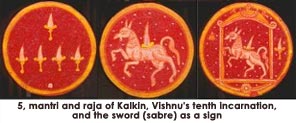

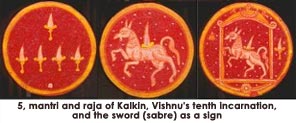

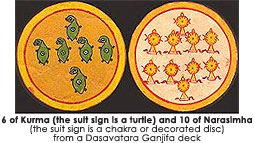

The main non-Mughal Ganjifa pattern is the Dasavatara. This word literally means "ten incarnations", referring to the human and animal appearances traditionally chosen by god Vishnu for revealing himself, in opposition to evil.

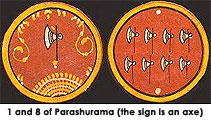

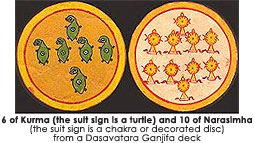

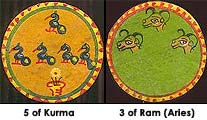

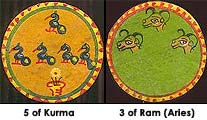

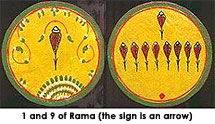

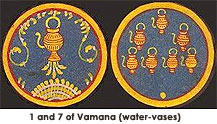

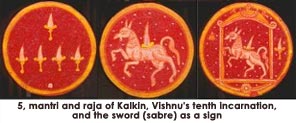

Such incarnations, usually ten but sometimes more, according to the local beliefs, are as follows: Matsya (fish), Kurma (tortoise) Varaha (boar), Narasimha (half man, half lion), Vamana (dwarf), Parashurama (Rama with an axe), Rama (hero of the Ramayana), Krishna, Buddha and Kalkin (the incarnation yet to come)

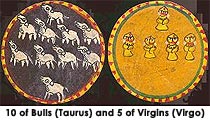

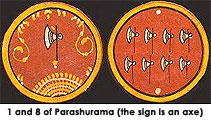

The number of suits in the Dasavatara Ganjifa are ten (five "strong" and five "weak"), and their signs reflect the features of the religious theme. Eight out of ten suits are standard, found in all decks, while two of them may vary from region to region, chosen among a number of optional ones (see the following table).

However, often Dasavatara Ganjifa decks have more than ten suits: two additional ones are common, but larger sets may count up to 20 or 24 suits (i.e. 240 to 288 cards, a rather unusual composition). Some names of the Dasavatara suits are those of the incarnations to whom they refer, while all the signs are symbols of their feats; besides the customary ones, some alternative signs are sometimes preferred.

Some names of the Dasavatara suits are those of the incarnations to whom they refer, while all the signs are symbols of their feats; besides the customary ones, some alternative signs are sometimes preferred.

| Suit Names (Incarnations) | Suit Signs (alternatives shown in square brackets) |

| Bishbar suits | |

|

Parashurama

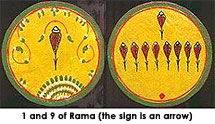

Rama

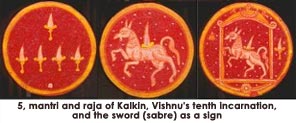

Kalkin

Balarama (optional)

Buddha (optional)

Jagannath (optional)

Krishna (optional) |

axe

monkey [ bow and arrow ] [ arrow ]

sword [ horse ] [ parasol ]

plough [ club ] [ cow ]

shell [ lotus flower ]

lotus flower

cow [ crowned bust ] [ blue child ] [ chakra ] |

| Kambar suits | |

|

Matsya

Kurma

Varaha

Narasimha

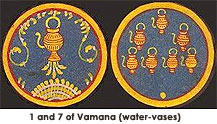

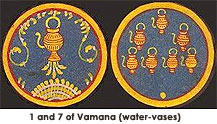

Vamana |

fish

turtle

shell

chakra (decorated disc)

jug / vase |

| additional suits (if any) | |

|

Ganesh

Kartikkeya

Brahma

Shiva

Indra

Yama

Hanuman

Garuda

Krishna

Narada |

rat

peacock

vedas (scriptures)

drum

thunderbolt

snake noose

club

small Garuda

flute

vina (Indian lute) |

The choice of using birds as suit signs is not terribly surprising, considering the many included in Hindu mythology, among which are the crow (vehicle of Shani), the peacock (vehicle of Kartikkeya), the parrot (vehicle of Kamadeva), the swan (vehicle of Saraswati and Brahma), plus a few mythical creatures such as Garuda (half man and half eagle, vehicle of Vishnu) and Arva (half horse and half bird).

The birds featured in Ganjifa cards (i.e. the pips) are small and rather stylized, but the suits can be told also by the colour of the background, and by the personages of the court cards, who sometimes hold the traditional sign (sword, shell, jug, etc.), or are recognizable by their particular shape.

-

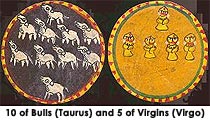

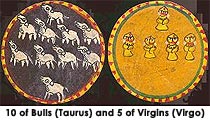

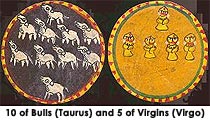

Rashi Ganjifa: Rashi (zodiac) Ganjifa is a twelve-suited pattern that features zodiac symbols as suit signs. The Indian or Vedic zodiac is similar to the Western one: it divides the year into twelve periods or "houses", each of which is identified by a symbol.

-

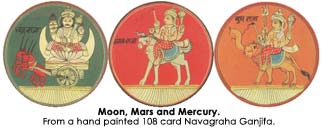

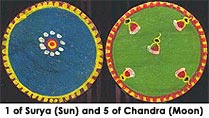

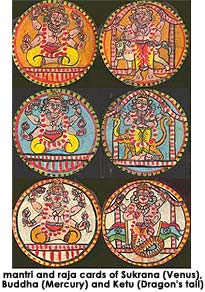

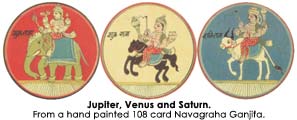

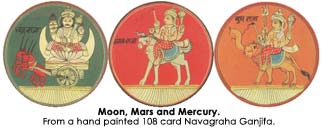

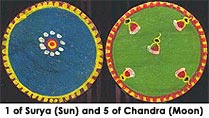

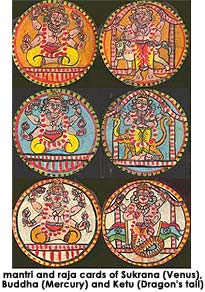

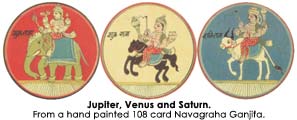

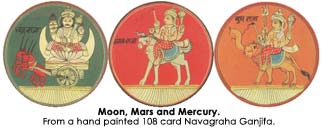

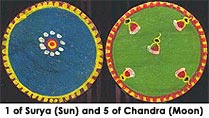

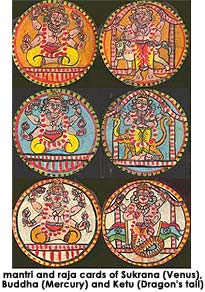

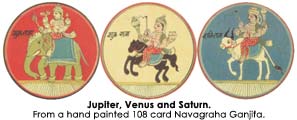

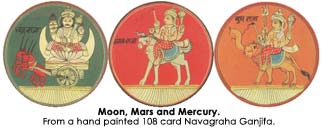

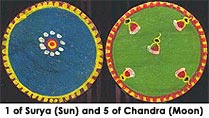

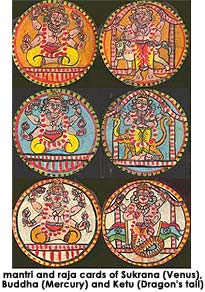

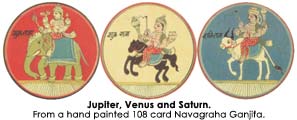

Navagraha Ganjifa: Navagraha means "nine planets". In Hindu culture, these planets are believed to bestow humans with special gifts, and are worshipped as gods (specific prayers are recited to each of them). In India this is an important cult; in fact, the Navagraha Ganjifa pattern was created at the beginning of the 20th century by Shankar Sakharama Hendre, whose project was to sell cards to raise enough money for building a temple dedicated to the Nine Planets, in Bombay. Although his goal was not achieved, the Navagraha Ganjifa survived. In this pattern each suit represents a planet; but the last two, Rahu and Ketu, are actually lunar nodes, namely the ascending node and descending node, respectively referred to as "dragon's head" and "dragon's tail", and often pictured as a bodyless head and a headless body. Each planet is a deity itself, to which a month, a zodiac sign, a color, a gem and a steed are matched.

The full series of planets (some have alternative names, according to the different parts of the country) are: Surya/ Ravi (Sun) on a 7 horse-drawn chariot, Chandra (Moon) on an antelope-drawn chariot, Mangala/ Kuja (Mars) on a buffalo or goat, Budhan/ Buddha (Mercury) on a lion with elephant's trunk, Guru/ Brihaspati (Jupiter) on an elephant or goose, Sukrana/ Sukra (Venus) on a horse, Sani/ Shani (Saturn) on an eagle or crow and Rahu (Dragon's head) and Ketu (Dragon's tail) who have no vehicles.

Besides the Ganjifa varities mentioned so far, some others exist: the Ramayana Ganjifa, a twelve-suited pattern inspired by the Sanskrit epic Ramayana, the Ashtamala Ganjifa, inspired by eight episodes of Krishna's life as a youth, and the Ashtadikpala Ganjifa which refers to the eight cardinal directions.

Ganjifa are traditionally round, measuring approximately from 20 mm to 34 mm to 120 mm in diameter.

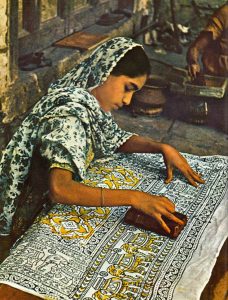

Today Ganjifa cards are made of layers of pressed paper, but in Odisha cloth is still used. At first, paper layers (normally six) are layered and glued together, primed with lime, dried, burnished, cut, painted and lacquered. The lacquer is made from Indian shellac (chapra) or other natural resins which give the cards the required stiffness, protection and smoothness in handling. Cloth cards are made from cotton waste rags, soaked and starched with glue made from tamarind seeds; when dry, by using a mold the starched cloth is cut into discs, two of which are glued together to make individual cards; a paste made from chalk is then applied to make the surface even, and the deck is finally painted. Paints were traditionally made from mineral or vegetable substances are today increasingly replaced by readily available synthetic colors.

The process of making cards is shared by the entire family of chitrakars. Much of the preparatory work is done by women. Pip cards are painted by junior artists, figure cards by senior ones. They begin on previously prepared colored backgrounds by first outlining the figure in white or lighter colors and then they successively paint the details in different colors finishing the figure with a thin outline in black. Each artist evolves a personal style in spite of his fidelity to traditional conventions.

The cards are painted plain red or orange on the back. Cards from Odisha have yellow, green, blue and black backs and increasingly in recent years, brown backs rendered in cheap paint made from lal mati (red mud). Occasionally one finds the backs decorated with a rim line or small central flower. Fully ornamented backs are rare as the artist has to take special care to make the backs identical so as not to create any tell-tale irregularities. Some decks are housed in a wooden box or case, often decorated with themes consistent with the pack's pattern. Each region has evolved its own distinctive type for instance, in Rajasthan boxes are short and oblong painted predominantly in green or crimson, in Sawantwadi they are cubic are commonly in red, in Andhra Pradesh they are long with bulging sides painted in green, in Mysore they are oblong or cubic, in Odisha cubic in black, brown and yellow and in Kashmir long boxes with floral patterns. The paintings vary from region to region, from floral motifs to elaborate processions. All boxes have a sliding lid.

Some decks are housed in a wooden box or case, often decorated with themes consistent with the pack's pattern. Each region has evolved its own distinctive type for instance, in Rajasthan boxes are short and oblong painted predominantly in green or crimson, in Sawantwadi they are cubic are commonly in red, in Andhra Pradesh they are long with bulging sides painted in green, in Mysore they are oblong or cubic, in Odisha cubic in black, brown and yellow and in Kashmir long boxes with floral patterns. The paintings vary from region to region, from floral motifs to elaborate processions. All boxes have a sliding lid.

The main centres of Ganjifa manufacture are Sawai Madhopur and Karauli in Rajasthan, Sheopur in Madhya Pradesh, Fatehpur District in Uttar Pradesh, Sawantwadi in Maharashtra, Balkonda, Nirmal, Bimgal, Kurnol, Nossam, Cuddapah and Kondapalle in Andhra Pradesh, Mysore in Karnataka, Puri, Sonepur, Parlakhemundi, Barapalli, Chikiti and Jayapur in Odisha, Bishnupur in Bengal and Bhaktapur, Bhadbaon and Patan in Nepal.

From this basic play, variations are derived. A univeral characteristic of Ganjifa games, whether played with eight, ten or twelve suits: the two court cards always rank highest in each suit, but in half the suits the numerical cards then rank in one order and the other half in the opposite order. The objective of the game is to win as many tricks as possible.

To a game in which the evocation of "your Rama did this" or "your Matsya lost and my Narasimhan won" was said to remit sins, Ganjifa today is a craft in crisis. In the coming years, unless the cards can make a transition from museum collections to the drawing rooms and card tables, it is an art which will become extinct.

Games are a common passion, a common pastime which cross all sections of the community. Playing or watching games form a highly significant aspect of culture, both because of their importance in peoples lives and their capacity to bring families and communities together and because of the degree of creativity and skill that go into devising them. No indoor games match the passion with which cards are played in India. One such card game, now facing extinction is Ganjifa.

‘Ganjifa’ is the name given to an ancient Indian card game. Quite aptly the name Ganjifa comes from the Persian word Ganjifeh which means playing cards. The specialty of these cards is that they are traditionally hand-painted. The cards are typically circular although some rectangular decks have been produced.

‘Ganjifa’ is the name given to an ancient Indian card game. Quite aptly the name Ganjifa comes from the Persian word Ganjifeh which means playing cards. The specialty of these cards is that they are traditionally hand-painted. The cards are typically circular although some rectangular decks have been produced.

.

.

The long and stable rule of the Chand Dynasty starting in the 13th Century, over the Kumaon region allowed the state to prosper and gave people time to nurture their creative side. This gave rise to the development of a new style of painting in the area referred to as the Pahari School of Painting. Around the middle of the 17th century C.E., Dara Shikoh's son, Sulaiman Shikoh escaped from his uncle Aurangzeb and sought asylum from King Prithvi Shah of Garhwal. He brought with him, as part of his entourage, two court painters, Shyamdas and his son Hardas. Though 19 months later the Mughal King was captured and taken away, the painters enchanted by the beauty of the region chose to stay back. The father and son were masters of the Mughal style of miniature painting. They were appointed as royal tasbirdar (picture-makers) in the court of the King of Garhwal and gave rise to a unique Garhwal style of miniature painting. Further, the matrimonial alliances between the Kingdoms of Garhwal and Kangra, prompted many artists from Kangra to come and settle in Garhwal. Their technique had a great influence over the Garhwal style of painting. With the conceptualization of ideal beauty, its synthesis of religion and romance, its unification of poetry and passion, the paintings of Garhwal are an embodiment of the Indian attitude towards love. The main subjects of the painting are Krishna Leela, Rukmini Mangal, Ramayan, Mahabharath, and Kama Sutra. The women are the focal point in the paintings. They are shown to be near perfect, extremely beautiful women with soft oval shape faces, with a delicate brow and a thin nose, full breasts and a tiny waist. Their ornaments and jewelry are depicted with intricate details. The clothes are often transparent. As compared to the styles of the paintings of other school of that time, the silhouette of women is slender. The trees are depicted as diminutive and round in shape. The glory and grandeur of the nature in the painters' immediate surroundings also reflects in the paintings. ?

This ornate craft represents a magnificent combination of two craft forms: (1) the skill of making products - from saddles to water bottles known as kupi out of camel leather and (2) of ornamenting these products. Nakashi is an ornate lacquer work on an embossed surface, in which gold leaf and/or paint is used for decoration and designing, in adjunct with other colours and other kinds of decorative ornamentation akin to minakari are used. The art of nakashi is supposed to have been brought to India by Mughal emperors who brought Usta artists (those who do the delicate and meticulous nakashi work).The Junagarh Fort in Bikaner stands testimony to the enchanting artworks created by these artists: the Anup Mahal in the fort is resplendent with golden lacquer work, spun into delicate floral and bird and animal designs. The Chandra Mahal and the Karan Mahal also depict examples of nakashi work. Since the critical requirement for nakashi work is a clean and smooth surface as a base, walls, pillars and ceilings are decorated with these glowing golden motifs, often set against detailing in radiant colours. During the time of the British in India, nakashi work on camel leather became popular. Camel hide was light and unbreakable, and camel-hide saddles and bags (especially as containers for water, since they were easy to transport without breaking) became common bases for nakashi work in this desert kingdom and adjoining areas. These water bottles/containers called kupis - ornately decorated with nakashi work, much in the style of the tradition of ornately decorated camel-leather saddles - were popular in Rajasthan, particularly in Bikaner. Their utilitarian value, quite apart from the exquisite artistic tradition they represent, has meant that they continue to be made till today. Nakashi work can only be done on a smooth and clean surface. After a smooth surface has been prepared (in this case, the body of the kupi bottle), the design or pattern is made. The design-making process is known as akbara. The designs are first made on paper. The outlines of the patterns are punched on the paper with pins thrust along the tracery of the designs. The design is then traced on the paper using indigo or black coal power, which filters through the pin-holes on the paper and traces the outlines of the intended design on the leather. The manouat is done over the akbara, and creates an 'embossed effect' on the desired pattern. According to Kamladevi Chattopadhyaya, the portion to be ornamented is raised by repeatedly applying a special preparation of shell powder mixed with glue and a kind of wood apple. Alternatively, sand from a ground earthen pot is mixed with glue and jaggery to create the required paste. The embossed surface is then painted upon. Usually a colour called paveri is applied first. Then, a colour made from sindur and rogan is applied. Bat is then applied to the areas where gold is to be patched. At a particular consistency of bat, gold is patched over the surface having bat. Detailing follows - this is done by inking (sihayi) with a sable-hair brush. The remaining surface is filled with different colours. As a particular surface rises it is painted in gold and other colours while the base is coloured black or red to make the shapes at the top stand out. The motifs in nakashi work are linked closely with the Mughal origin of this craft in India. In depiction, they closely follow a style of Mughal miniature paintings - especially court paintings - whose hallmarks include acute detailing, intricate designing, a superbly deft use of colour and line in a small space, and a very ornate effect, shot through with gold work. The patterns created are also distinctly Mughal, and are closely allied with relief detailing in the ornate aspects of Mughal architecture.

- Cleaning the hide: This involves removing the hair from the raw hide, keeping the hide in a diluted lime-water (jevasi) solution, for upwards of two weeks, and then shaving and cleaning both sides of the hide using knives with curved handles.

- Treating the Hide: This involves

- keeping the cleaned hide in a mixture of salt, diluted acid and water in a pit for around 10 days; and

- keeping the hide in a solution containing an extract of the bark of the babul (Acacia arabica) tree, which is a tanning agent (the quantity of the tanning agent is increased slowly during the month);

- Stitching the hide back into shape with jute fibre and hanging it, filled with water, for four days (emptied eight or nine times); and

- repeating the process of filling the hide with water and emptying it eight to nine times, this times with the hide inverted.

- Tanning: Immersing the hide in a pit of salt water for two weeks, to a month, or longer, depending on the weather. The tanning methods in Rajasthan are fairly primitive, and continue to be seriously affected by rains and/or very high temperatures, both of which are not conducive to tanning.

- Drying the hide and softening it: This involves

- cutting open the stitching, flattening the hide and stretching it out to dry;

- oiling the dried hide;

- washing it in water several times to remove the salt; and

- softening it by rubbing it continually with the soles of the feet.

- Soft balu rait (sand);

- meetha chuna (lime), used for drying and hardening; and

- pilli mitti (clay) that acts as a base

- Golden lacquered nakashi, in which flowers and leaves are golden and the surface is filled with colours.

- Golden lacquered nakashi with mina, in which colour is applied to flowers and leaves also.

- Golden lacquered zangali, in which the work surface remains emerald green and the rest of the design is in different colours.

- Golden lacquered tantla, in which the surface is golden, the flowers and leaves are depicted in colour, and the details are done in white.

- Ranga Baijee, in which the work the surface remains white, the flowers and leaves are painted with transparent colour and are partly shaded, and miniature paintings are created within the designs.

- Turanj, in which, identical pattern(s) are transcribed at the base and the top, like along the upper and lower rims of a lampshade.

- Chande, in which a small and intricate design is repeated all over the decorated area.

- Bharat, in which the surface to be decorated is filled with motifs and patterns, with little visible surface space.

The gharchola is the traditional Hindu and Jain wedding sari. The numbers of squares in it is ritually important - the number of squares are multiples of nine, 12, or 52. It used to be made of cotton but now silk is predominantly used. The gharchola is essentially a bandhani sari. The technique of tie-dyeing cloth so that many small resist dyed spots produce elaborate patterns over the fabric is known as bandhini (bandhej) in the western Indian state of Gujarat.

Bandhanis are of various kinds:

|

According to Lynton: The 'ghar' is gharchola can be directly translated as 'house'; however, it also connotes 'birthplace' and/or 'family', suggesting perhaps that the sari is from the home or birthplace of the brde (Lynton: p. 191).

Ghazipur wall hangings are interior décor items that are handcrafted in the small city of Ghazipur in Uttar Pradesh. These traditional handloom products are woven by skilled craftspeople using a blend of different colors. They combine different yarns including jute and cotton to ensure not only strength but also an unusual unique texture. The use of differing textures also forms a part of the presentation of the patterning and design. These Ghazipur wall decorative hangings are woven on the handloom and their intricate patterning, colors and designs have a wide appeal. A large range of designs bears testimony to the skill of the weavers from representation of figures of Hindu gods and goddesses to intricate and detailed landscape arts with patterns of houses, lawns, forests, interiors, birds and animals.