The word kundan means highly refined gold. This technique of jewellery production uses purest form of gold to set the precious and semi precious stones like rubies, diamonds, emeralds and sapphires. Jadia Kundan is an Indian gemstone jewellery, elaborate ornaments were made in the royal state of Rajasthan to be used by rajput families. This type of jewellery is supposed to be introduced in India during Mughal era. Jadau kundan is one of the oldest forms of jewellery that exists in India even today. Kundan Jewelry is created by setting carefully shaped, cut and polished multicolored gemstones into exquisitely designed pure gold base. Gold is self-weldable even while cold, through compressions; no soldering is required to create a solid wedge. The wedge thus formed keeps the stone at it place. The elaborate process, begins with first skeletal framework called Ghaat , thereafter the Paadh procedure takes place, during which lac or the wax is poured onto the framework and moulded according to the design. In the following Khudai process, fitting of stones or the uncut gems is done into the framework, followed by Meenakari , which involves enamelling to define the design details. Finally the gems are polished using Chillai process. A silver or gold colored foil is kept below the stone to enable reflection of light through the stone. The foil brings out the brilliance in the light reflected and therefore the stones color looks improved. The Jadia Kundan is again finding its place in the Indian market. The patronage has vanished but the kundan work is imitated on silver for commercial purposes. The cheaper versions of the traditional jewelry are popularly used. The expensive gold and precious stone kundan jewelry still finds the place in Indian brides trousseau.

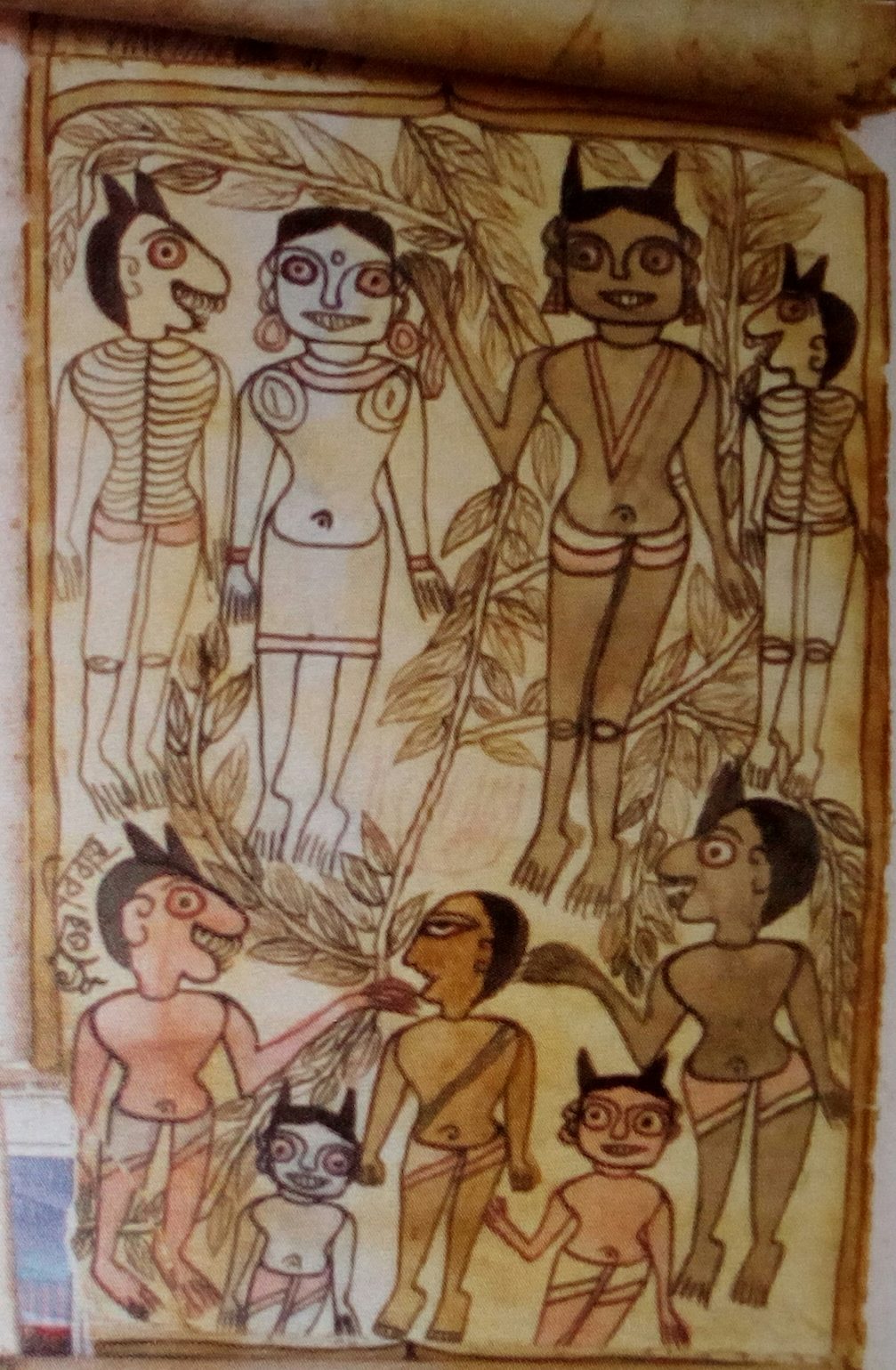

With over four million people, the Santhal tribe is among the third largest in India, largely inhabiting the tribal tracts across West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Assam, Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand and Chattisgarh. The Santhals have been identified as belonging to pre-Dravidian ancestry even as history recorded their existence only since late 18th century, having an ancient lineage with a rich diverse cultural identity. Originating from the Austro-Asiatic linguistic group sometimes referred to as the 'Mundari' group of languages, the Santhals area also ethnically related to other tribes of that area such as the Hos, Kharias and the Mundas. The story of their origin and the legends of the Santhals define their history. Their myths of origin trace back to the mythical lands of Hihiri Pipiri, Khoj Kaman, Harata Mountain to Champa and ultimately into modern history at Chota Nagpur. The beliefs of the Santhals are based upon the sprits that lie behind all their natural power. The Santhals refers to these spirits which are behind all benevolent and malevolent natural power both as Bongas, their themes are usually based on birth of Santhals, Santhal revolution, social aspects, myths, chaksudana etc. There are around 70 Patuas in the Majramura village in Kashipore block of Purulia of which some make and sing the Santhal stories. Santhals are famed as Jadupatuas, or the magic painters. The primary reason for this title is for the Chakshudana genre paintings they paint for the Santhal families of the recently deceased. The art historian, Mildred Archer, identified seven distinct themes of Jadupatua painting other than the Chakshudana pata are Death's kingdom, Baha Porob, Santhal story of creation, Thakur Jiu, Satya Pir, Jatra scrolls.

Varanasi/Banaras is a high-quality weaving centre known for its wide variety of techniques and styles and its famous silks, with zari. The figured silk brocades of Banaras have densely patterned motifs in gold thread (zari) or in silk, which creates a three-dimensional impression. Banaras fabrics, according to Lynton's The Sari, find mention in 'several early first millennium Buddhist texts', leading to the conclusion that 'Varanasi seems to have been a centre of fine textile weaving for at least two millennia, although it is unclear as to whether these textiles were of silk or cotton.'

-

ZARI BROCADES: In which the patterning is in zari or gold/silver thread.

The kincab/kinkhwab is a heavy gilt brocade, in which more zari work than underlying silk visible. The zari comprises more than 50 per cent of the surface. Often used as yardage in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these are popular wedding saris nowadays. The bafta/ pot-than / baft-hana are lighter in gilt brocades than the kincab, and more of the underlying silk is visible. The zari comprises less than 50 per cent of the surface. -

AMRU BROCADES: In these brocades, the supplementary weft patterning is in silk and not in zari. A traditional Amru brocade is the tanchoi. The tanchoi 'is a …densely patterned, heavy fabric…with no floats on the reverse - the "unused" threads are woven into the "foundation" at the back. Traditionally, the face of the fabric has a satin weave ground (warp threads) with small patterns made by the weft threads repeated over the entire surface' (Lynton: p. 56). It is believed that in the last half of the nineteenth century, three Parsi brothers by the name of Chhoi learnt the technique of weaving these brocades in China and introduced it in Surat (Gujarat in western India). A descendant of the brothers continued to makes tanchhois in Bombay till the 1950s but was forced out of business by the less expensive versions of the Varanasi weavers. [tan = three; tan Chhoi = three Chhois]

-

ABRAWANS: Muslin Silk/Organza Base: In the third variety, the ground material is a transparent muslin silk or organza, with a zari and/or silk thread patterning. So this can be a zari brocade or an amru. The amount of zari visible can also vary, and can cover more or less than 50 per cent of the base material. A sub-category is the 'cut-work brocade' in which the 'transparent silk fabric has supplementary-weft patterning woven in heavier, thicker fibres than the ground. Each motif is not separately woven in by hand as a discontinuous weft; instead the 'threads extend the entire width of the fabric, leaving floats at the back that are cut away by hand after weaving' (Lynton: p. 56). Another sub-category is the tarbana (woven water) in which the weft threads of the ground are zari, not silk, thus creating a metallic sheen. 'Several other weights and shades of supplementary-weft zari are used to create the patterning,' creating an extremely rich textile.

Jamakkalam handloom weaving has been recognized as a symbol of India's traditional cultural heritage with modern functionality across the globe. Originating from the Erode district in Tamil Nadu, this special type of weaving has been practiced since the colonial times in Bhavani town. It received the status as a Geographical Indication in 2006 and since has been an object of textile heritage. Although Bhavani Jamakkalam is typically weaved in the form of carpets and blankets, there is surging demand in new markets of production. The weaving has been recognized as authentic to the Bhavani town which is known for its enormous textile industry. Its second name is the "Carpet City" which then grants more fervor to the location and increases its cultural and economic value. The industry started to become independent and claim ownership since the colonial rule. During this time, in the 19th century, a group of weavers called the Jangamars started producing blankets using coarse cotton threads that were called as Jamakkalam (Neve 2005). Its popularity led to the replacement of traditional saris and clothes, making it a signifier of cultural strength and nationalism. Since then, the weaving is done in two ways, depending on the purpose of production. The first type of Jamakkalam is made using coarser cotton threads which are dyed into colors. Since the rough raw material is used, the designs are not too intricate and it results in the making of carpets with colorful bands. The second type results in detailed designing that is produced as bags and saris. The raw material used in this kind of weaving is artificial silk which is soft and can be woven in different designs. The Jamakkalam saris would have border designs and giving the traditional weaving a modernistic fashionable edge. The weaving is conducted using pit-looms which are made of wood. The arrangement of the loom is such that the threads are stretched horizontally from end to end. The weaver operates the loom through pedals with his legs and constructs the design by enabling the shuttles to move across and over the threads stretched. Traditionally, the Jamakkalam production would take place in the houses of the weavers independently. Since the 19th century, there has been an expansion in production and investment in technology that has led to the weaving being was carried out on handlooms in specialized centers of artistry supervised by the master weavers. The industry occupies most of the population in Bhavani, with women forming two-thirds of the workforce. Since inception, the industry has been supporting many livelihoods and hence, it requires immediate investment and transformation to match with today's healthy living standards. In addition, there is a high need to safeguard this industry from increasing competition and preserve the art as a part of India's heritage (Hussain 2019). However, with increasing taxes and high cost of production, there is a constant negotiation with the industry and the weavers. Hence, even after being featured in the stores of the leading Swedish housing company- IKEA and gaining exposure worldwide, there is a pit of empowerment that has to be filled for Jamakkalam as an art and the weavers.

Originally made in karpas cotton cultivated on the banks of Brahmaputra, Contemporary Jamdani is worked on cotton, mulberry silk and cotton-silk. The vibrant rich colours of Jamdani are made through a tapestry technique. Small shuttles of coloured silk or cotton yarns are passed through the weft. Each individual motif was woven separately. The thread of the shuttle was left hanging at the back of the sari after the motif was done. This technique is therefore known as discontinuous weft. Hand weaving of Jamdani is a labour intensive process.

Goldsmiths and jewellers constitute one of the largest communities of craftsmen in Pakistan. Every major town has one or more sarafa bazaar and lavishly stocked jewellery stores while small villages have at least one goldsmith each. The reason lies not only in the Pakistani women's passion for ornaments but also in history.

Though gold and silver work is a traditional craft on some islands, local work is not easily sourced. Most of the jewellery in shops comes from outside the country particularly from Sri Lanka, which is also a source of fine gem-stones. The bulk of local artisans are now working in local materials.

While gold (followed by silver) has always been the most used metal for traditional jewellery, ornaments made of clay and lac bangles are also popularly used in Assam. In Barpeta and Goalpara, in Lower Assam, stones are set in the gold ornaments. Initially, gold was locally available, flowing down the Himalayan rivers, and the Sonowal Kacharis tribesmen were engaged in gold-washing along these rivers. A sonar could belong to any caste.. Jorhat in Upper Assam makes traditional Assamese jewellery, and people flock there to procure the exquisite Assamese jewellery. Assamese jewellery include the doog doogi, lokaparo, jethi poti, bana, thuriya, gaam kharu, gal pata, jon biri, dhol biri, and keru, all of which have also encouraged modern jewellers to begin producing similar designs mechanically. The jethi poti is a broad band of cloth on to which is placed a row of small medallions with a central pendant. The most interesting piece of Assamese jewellery is an ear ring that resembles an orchid known as kopo phool. It has the appearance of two small shoes hanging together and attached to a floral portion on top. This is connected to a chain that goes around the ear and is generally made in 24 carat gold. Lokaparo is another typical ear ring, which has two birds placed back to back in gold ruby and mina or enamel work. A broad bangle with a clasp called gaam kharu is made in silver with gold polish. Bana or jonberi is a crescent-shaped pendant filled with lac for a cushioned effect. The front is studded with rubies while the back always has enamelling.

Bihar has a rich tradition of jewellery-making. Tribals wear a variety of jewellery made from natural materials as also from bell-metal and brass, especially as anklets and bracelets. Delicate ear rings worked in filigree with various designs are worn by the Santhal women. Small bells or ghungroos are held together by delicate chains and worn by the women. Even today the tribals use wild grass twisted into necklaces as ornaments. Bright feathers are used, both by the men and the women, to decorate their hair and turbans. Munda girls wear necklaces of beads, silver, and brass. A lot of the tribal jewellery has designs of flowers, berries, and leaves. The jewellery worn by the peasants of Bihar takes its designs and motifs from nature and uses floral patterns. The paunchi, which is a bracelet made of hundreds of small silver or brass jasmine buds strung together, is a faithful replica of jasmine buds. Women also wear a kardhani, for the waist and chudha for the wrists. Tikuli is ornamental work on fine glass done with wafer-thin tabaque (gold or silver leaves) and worn by women on their foreheads. The jewellery worn by the Muslim women is quite different from that worn by the Hindu women. The silver jewellery imitates the kundan work made for the Muslim wearers and the hanging jhumkis are more fragile in appearance than those worn by the Hindu peasant women. The border areas have both an Indian and Nepalese influence. Some interesting jewellery forms are associated with the local superstitions and religious customs. Small amulet boxes are made to ward off the evil eye and are worn by the people of all communities.

The precious-jewellery craft of Delhi received great patronage from the royalty in the past with the result that it became well established in the city. The demand for fine jewellery still continues, and has sustained the craft. Apart from jewellery made with gold and precious stones, a vast quantity of silver and costume jewellery is also made in Delhi. Delhi is also an important crafts centre for minakari jewellery. Minakari or enamelling is an elaborate technique combining goldsmithy, gem-setting, painting, and engraving, as well as the use of various colours. Minakars are highly skilled jewellers, with their skill having been handed down through the centuries. Precious stones are set into gold etchings of birds, flowers, and fish. The vibrant enamel colours are filled in painstakingly as in a miniature painting. Heat is applied to enhance the richness of the colours. The end result is a wonderful interplay of brilliant colours and designs. Silver ware is also made in Dariba in Chandni Chowk. Household utensils in all forms and designs, plain as well as ornamental, are available here.

A wide range of jewelry is made in Goa using a variety of material and prices to suit all pockets, customs, communities and ethnic groups. Silver lac-combs, with the central flower designs set with a red gemstone, are extremely popular with the women of Goa. As is both silver, gold and other metals.

Agate, silver, and bead jewellery are among the many forms of jewellery made in Gujarat. Agate is processed and made into ear rings, nose rings, bangles, and necklaces. Silver jewellery is made from silver bars which are locally purchased. These bars are first converted into sheets and wires and then into bangles, nose pins, ear rings, and anklets. The concentrated zinc mixed in the silver bars give it a different appearance. Kutch is the main centre for the silver craft in Gujarat. The chief areas of silver work are Anjar, Bhuj, and Mundra in Kutch district. Porbandar, Jamnagar, Surendranagar, and Ahmedabad also have a tradition of crafting silver jewellery. Traditional communities, still use jewellery crafted in styles that have existed for centuries. Artisans use thread, zari, beads, and lac in the jewellery. These ornaments are worn by the tribal and rural women who have sustained this craft.

Haryana is well-known for its jewellery, crafted in silver, bone, and lac. Folk jewellery follows traditional designs which have remained unaltered. Techniques of ornamentation like repoussè, chase, filigree, and enamelling are common, while beads are blown into beautiful shapes and sizes. Silver jewellery made in Haryana can be divided into two broad categorises: the heavy ornaments worn by the rural folk and silver jewellery worn by urban women. Silver belts are a popular and are usually stiff broad bands that are flattened and twisted. Repoussè work and filigree and enamelling techniques are employed.

There is an entire gamut, ranging from expensive to low-price ornaments. Gold and silver jewellery studded with precious stones and pearls and decorated with fine enamel work can be found here. Jewellery made of lead, copper, brass, ivory, beads, ornamental threads, wool, seeds, berries, and cowries is also made. Glass and lac bangles are worn by all communities. Benda is an ornament for the forehead, necklaces are known as hansuli and mangalsutras, and the nathuni is the nose ring. The jhanjars or anklets are made of clove-shaped beads of silver cast in one piece called lauang kasauthi. Rewa and Indore are famous for lac jewellery. The ornaments made include chokers, ear rings, rings, hair ornaments, and large octagonal bead chains made in traditional styles. Lac is placed over tin foil and melted, so that the foil is completely covered with lac. These ornaments have a golden sheen. Gwalior is an important centre for glass-bead ornaments such as necklaces, ear rings, rings, and belts. Artisans also combine glass beads with wood, shell, rudraksha, and copper and white metal to produce more attractive designs.

The appeal of Maharashtrian jewellery is in its solidity, volume, and elegance. So simple is it in concept that the jewellery can be made with chunks of gold or silver, with gold plating, or thin gold sheets filled with lacquer and yet retain its beauty and originality. Each traditional ornament made and worn in Maharashtra has a local name. Sari is a masterpiece of ingenious simplicity. It is a circular golden tube, or two wires twisted together with a spiral design at each end. The ends are joined with a hook in the front. It is stiff and worn quite tightly around the neck. Mohanmal is another simple creation, made of moulded beads of different designs. Gathla and putalimal are gold coins strung together to make a necklace. The coins in the smaller necklace, the gathla, are usually inscribed. The putalimal is much heavier. Chandrahars are circular rings linked to each other. Goph is literally a rope of gold, chitak is a strip that circles the neck quite tightly, and toda is a thick, ornamental bracelet that sits heavily on the wrist. Hupri, near Kolhapur, is foremost among the silver jewellery making centres in Maharashtra. The items produced are necklaces, ear rings, armlets, hair pins, waist chains, rings, and key chains, each of which bears the stamp of superb craftsmanship.

Gold is commonly used by the tribes to make jewellery. The khasis and jaintias are fond of jewellery, and the women are specially partial to gold and coral bead necklaces. A string of thick red coral beads worn by them during festive occasions is called the paila. The jewellery of the khasis and jaintias is alike and the pendant they wear, called kynjri ksiar, is made of 24-carat gold. Exquisitely crafted ornaments of gold and silver and gilt beads form part of Meghalaya's rich dancing costumes. The gold beads are not solid but the hollow sphere is filled with lac. Many of these ornaments as well as the head gear is decorated with diamond- like crystals of metal. Amulets, bracelets, necklaces, and anklets are manufactured locally. The Garo ladies wear a necklace called the Rigitok which consists of thin fluted stems of glass strung with fine thread.

Odisha is famous for its silver jewellery, specialising in the making of anklets. The painris ---or rua painris as these anklets are locally known --- are simple and elegant, tubular and oval in shape and curved slightly to the side to face the inner side of the ankle. It consists of various striped bands with circular lines and clusters of overlaid beads in conical shapes, with at least four on each painri. Two pairs of flower buds around a heap of small beads arranged in a circle are placed between bands. Paijam, another kind of anklet, is flexible with the interlacing of various chains joined together. The first row consists of small circular metal pieces is linked to another flower shaped piece below by two wires. These are, in turn, joined to the bigger flower shaped pieces set below on a thin plate, the latter forming the third row. Semi-circular wires link one flower piece to the other. From these wires hang small hollow balls, giving the look of a band of lace. On one end lies a coin-like metal piece with a swan, peacock or flower motif on it.

In Tamil Nadu jewellery has been traditionally worn and it is a rare person who will be seen without some ornament. The jewellery making tradition, which dates back to the Sangam era about two millennia ago, had acquired a high degree of excellence and the pieces worn today are similar to the ones worn then. Gold in Tamil Nadu is considered an auspicious metal and good for health. Ornaments are made for every part of the body except the feet, where it is worn only by gods and kings. There is the elaborate thalaisaamaan, worn on the head and hair; this is the traditional bridal jewellery which is set with stones. This was worn by devadaasis/temple dancers who were considered wedded to the deity, and so came to be called temple jewellery. The pieces of the ornaments are shaped like the sun and moon to invoke their blessings, and are set with rubies interspersed with emeralds and uncut diamonds. The pieces are worn on the parting of the hair, along the forehead. Behind the hair decoration is the raakkodi or naagar which is a stone-encrusted piece shaped like a five-headed snake with a swan in the centre. Below this is the jadanaagam or hairpiece that covers or follows the shape of the plaited hair -- this set in stones (rubies and diamonds) and has an intertwined design. It starts with stone-set crescent moon and a piece shaped like a thaazhambu or a screwpine flower, after which the longitudinal piece actually starts. Jewellery for the ears is varied; older women in rural areas wear a heavy gold ornament called paambadam made of six earrings which enlarges the holes in the ear lobes. Ear studs can be kadukkan (single-stone), kammal (lotus-shaped with rubies or diamonds), jimikki (bell-shaped ear-drops) and lolaakku ( ear-drops of any design). Maattal is the ornament made of gold or pearls which is hooked to the earring and then attached to the hair above the ear. The other ear ornaments which are not commonly found nowadays are kathribaavali, kuruthubaavali, koppu and jilpaabaavali which are worn on the inner or outer ear or above the ear. Ornaments on the nose are mookkupottu (single stone), besari and muthu (made of eight diamonds), hamsa besari (shaped like a swan), nathu (made of stones) and bullaakku which is worn suspended from the central part of the nose. The others are worn on the right or left nostril according to tradition. The main neck ornament is the thaali the mangalsutra or marriage talisman, which was earlier worn on an auspicious thread and now is worn on a gold chain. The most important part of this is the pendant whose design indicates the community of the wearer; it could be shaped like a thulasi (holy basil plant), the conch and discus of Vishnu or it could be heavily stone-studded as worn by Chettinad women. The other varieties of neckwear are addigai (made of rubies and diamonds), kempaddigai (made of red stones), maangaamaalai (made of stone-studded gold mangoes strung together), pearl necklaces, kaasumaalai (gold-coin necklace), salangai (made of gold beads with black or coral beads), rathna kanti (ruby necklace) and asli haasli as it is known in northern India which is a stiff stone-set necklace which is supposed to protect the collar bone. An upper arm ornament called vanki is usually intertwined in shape and a stone-inlaid piece set in gold; the shape indicates snake or naaga worship. Naagavathu is an ornament for the same part giving the appearance of a coiled serpent and kadayam is an armlet worn by young girls. Bangles or valai for the arms are in plain gold with designs or set with stones. Gettikkaappu is a gold bracelet, thoda is a bracelet with a stone-set crest. An inverted v-shaped ring called nali to match the vanki is given to a bride by her maternal aunt. Oddiyaanam is a gold or silver belt worn tight around the waist; those with stone-encrusted centres are called asmogappus. Anklets are of various types: ganja golusu (heavy variety with bells that tinkle), thandai (stiff anklets with bells that tinkle) and kaal kaappu (worn mainly by children and believed to protect their ankles). On each second toe is worn the heavy silver metti, the siththu are two rows of heavy silver wires keeping the meti in place and peeli is designed like a crest and worn on the third toe. The concept of R'ta or cosmic order is found in the designs of the ornaments. There is perfect symmetry whereby the left side of a jewel-piece is a mirror image of the right side. Even nose-pins are matched for symmetry (nathu on one side of the nose and besari on the other). The jewellery in Tamil Nadu has close settings with stones deeply embedded in gold. Open-setting work is not done here. Wax is the base on which the design is fashioned in gold and the stones are encrusted, and the effect is heavy and three-dimensional. Tribes in Tamil Nadu like the Todas, Badagas, Kotas of the Nilgiri district have silver and other metal jewellery. The ornaments are huge, heavy and intricately carved. Toda jewel pieces are made of bent wires and shells. The Kadar tribe of Aanamalai hills have bead jewellery; these are bought and sold by Nari Kuravas or gypsies.