The pottery in Rajasthan has several distinct characteristics. Since water is such a precious commodity here, water pots have small mouths to prevent spilling. The shoulders of the pots are painted with black and white patterns. Alwar is noted for its paper thin pottery, known as kagzi pottery. This has extremely thin walls and is very light-weight. The double-walled surface is cut into different attractive patterns to help circulate the air and keep the water cool. The pottery in Pokhran has geometrical etchings. The painted pottery of Bikaner has lac colours to which gold has been added. The Nohar centre of Bikaner is famous for terracotta products. Beautiful terracotta horses for religious offerings are made in Jallore and Ahora districts while terracotta toys of Nagaur and Merta are popular articles sold in local fairs. The main pottery centres in Rajasthan are Jaipur, Ajmer, Bharatpur, Sikar, and Sawaimadhopur. The craft of terracotta is practiced widely in Sawai Madhopur of Rajasthan. Products such as decorative figurines of animals, decorative plaques, votive plaques, idols, toys, and pots are produced under this craft-form. Tools such as potter's wheel called chak, finishing tool called bhal and tools for engraving decorative patterns are required for the crafting process. In Rajasthan the craftspersons from Pokaran (Pokharan) produce an unusual pottery that is light pink to an almost white colour and has a fine textured feel. These properties are unusual and unlike the red terracotta pottery as the process and techniques followed here are detailed and complex. It is a laborious and time taking procedure that involves beating and grinding the clay by the craftspersons that results in its particular texture and fineness. As the raw clay from this area of the Thar Desert is salty, hard, stony and has rocky ridges the process of refinement requires great skill since it is quite arduous to manipulate the clay in order to craft the items. To achieve the smooth texture and remove uneven particles, the clay needs to be filtered multiple times through a sieve. Once the clay is molded into the desired shape, it is fired. The Pokaran products are reputed to be durable, tough and are known to be long lasting. At every stage of making the master's expertise and careful judgment plays a part in producing the final product. Craftsmen of the caste of Kumbhakars prepare hand crafted products. These include the well known floating clay lamps and lamps in the shape of tortoise and fish bowl for curds, girdle, to make bread. They also shape animals of variety more than 100, including snail, elephant, giraffe, horse, camel, pig, bull, cat, dog, rabbit, camel cart, owl, duck, crocodile, peacock, birds, cock, cow, Nandi, fish, frog, etc.; wall hangings with different animal head shapes, pots with figures of men and women. Besides creating terracotta pots and vessels, local potters also produce a variety of clay toys and idols in Rajasthan. Idols of Ganesha and Ramdeo, toys such as camels, lions, peacocks, elephants, horse, rats and rabbits and other animal figurines are created under this craft-form. Tools such as potter's wheel, moulds and carving tools are used for the crafting process.

Maddalam is considered to be a divine instrument or “deva vadys” because of its inclusion as a major accompaniment in the dance of Shiva. It dates back to the 13th century. It is basically a percussion instrument used in Kerala as an accompaniment to temple art forms like Kathakali, Panchavadyam, Keli, etc. The Maddalam is cylindrical in shape and is still chiselled out of a single piece of jackfruit wood. The hollow ends of this elongated drum are tightly strapped with a combination of cow and buffalo leather to create the required percussion sounds. There are two varieties of Maddalam: Suddha Maddalam and Toppi Maddalam. The former is tied around the waist of the drummer with a cloth while the latter is suspended from the neck.

In warm, humid climates, the mat is the most popular floor covering to sit or to sleep on. Variations in local climate, materials, ways of life and traditions in different region and among different ethnic groups have lent a rich variety of shapes, forms and textures to both mats and basketry and a great diversity in the manner of their use in Bangladesh. One of the most popular of the mats produced is the madur. The madur mat production is an organized industry by weavers of the Mahishya caste and is mainly woven in the Midnapur district. Here the madur grass is steeped in water for a minimum of twenty-four hours and then sliced to the required thickness after which it is dyed red. The mat is woven on a simple bamboo frame loom, the warp is cotton thread and the weft a soft thin reef, madur kathi. Three types of madur mats are woven ekhrokha, dorokha and masland. The Masland mat is a very fine textured and made of carefully selected reeds with beautiful geometric design woven on it.

Madur is the most popular of the mats made in West Bengal. It is woven mainly by the weavers of the mahishya caste in the southern parts of the district of Midnapore which covers the whole coastal area of West Bengal west of the river Ganga. The madur mat is woven on a simple bamboo frame-loom. The warp is cotton thread and the weft is a thin soft reed called madur kathi, which is cultivated in the Sabong, Ramnagar, Kholaberia, Sadirhat, and Narayan Chak in Midnapore district.

Madurai Sungudi is a cotton fabric from Madurai in Tamil Nadu. This traditional textile is produced using the tie-and-dye technique. At one time sarees were the only products, but now the fabric is also used to make shirts, salwars, shawls, handbags, bed sheets and pillow- cases. The count of the yarns used in the warp and weft are 80's and 100's respectively.

Maheshwari weaving is commonly known for its silk and cotton saris. The sari is comprised of either pure cotton or of mixed silk and cotton thread. Silk warp with a fine count and cotton weft is used in the weaving. The pallus of the sarees are woven with silk weft. Being a lightweight fabric, Maheshwari textiles are also used to make dress materials and dupattas. The sari derives its name from the town of Maheshwar in West Nimad district of Madhya Pradesh, located on the banks of the Narmada river. Legend has it that it was set up by the Queen Ahilya Bai Holkar - the light, yet rich maheshwari was once the exclusive privilege of royalty. Ahilya Bai built a temple and a palace with beautiful carvings - it is estimated that these could well have provided the inspiration for the designs of the maheshwari sari.

-

Field: Usually there are no motifs in the main field. The buttis so common to the chanderi are definitely not in the maheshwari, though very fine checks or stripes can sometimes be found in the field.

-

Borders: Traditionally, these have narrow bands of supplementary-warp patterning in zari or coloured silk. (Today, maheshwari borders are often broader.)

-

End-piece: The pallu (end-piece) is quite distinct - with broad and narrow white bands (either the five-band Maharastrian style, or a series of bands of different widths) across the base colour of the sari.

The colours and textures are a play of weft colours, subtly different from the warp yarn. Soft and gentle colours are more common; occasionally a brighter colour can be found.

Janakpur, a city in Nepal's eastern terai, is a Hindu pilgrimage site with an ancient heritage. God Ram and goddess Sita are said to have been married there, and each year Janakpur celebrates Ramnawami (the birthday of Lord Ram) and Bibah Panchami (the marriage of Sita and Ram). People come to Janakpur from all over the world to see the Janaki Mandir, a temple dedicated to Sita. Janakpur was once the capital of a kingdom called Mithila (whose territory extended into the present day Indian state of Bihar) and it remains today the centre of Maithil culture in Nepal. Most Maithil people live in small villages, usually with no more than around 100 households. House walls are made from bamboo or thatch, plastered with a mixture of cow dung and mud. The roofs are thatched, sometimes tiled, with most houses having a fenced courtyard constructed with mud and cow dung.

The Malars of Chattisgarh are found mainly in Sarguja; some of them are also found in Raipur. The metal-casting techniques used by Malars are similar to those used by the Jhatur (also called Malars) of Raigarh. The wax used is an alternative to beeswax; known as Dhuvan or Dhup, the wax used is made from the gum of the Sarai tree or from Ral (resin). In contemporary times, some metal-casters of Raigarh use wax on the coating of Dhuvan. By and large, pure Dhuvan is used with no other material mixed with it.

The papier mache products made include animals and birds like cocks, parrots, and pigeons. Papier mache folk products, especially the bowls of Banasthali, have a very attractive appearance. The making of decorative shelves and containers is also a highly evolved craft of western Rajasthan. The raw materials are waste paper and clay. The big containers or kothis are light and long-lasting and are decorated with pieces of glass, paint, and relief work. Papier mache is a commercial craft now used for marriages decorations and as props and backdrops for jhankis or festive occasions. Bharatpur and Ajmer are important centres. Palai in Tonk district is famous for furniture made out of papier mache. Jaipur is well-known for toy animals and birds made out of papier mache. These are highly imaginative, well modelled, and delicately coloured.

The Mangalagiri Saree is a fine count saree normally woven with 80’s combed cotton yarns for both the warp and weft, with extra warp designs in the border. The speciality of the extra warp design is the combination of twill, rib and diamond weaves; these are arranged side by side continuously without any gaps. Zari is used for the extra warp design in the borders.

Rajasthan is known as the land of marble. Makrana in Nagaur district is the main centre for marble. This marble is used mainly for making domestic wares. The white marble is called sange malmal because of its pure white look. The other colours of marble are rose, salmon pink, light green, gold, saffron, and lemon. The marble from this centre is said to be the marble with which the Taj Mahal has been built. Kishori is a village near Alwar which is engaged in the craft of making large size traditional deities in marble. The statues are highly ornamented. Jaipur is the main centre for making products from marble. The religious images made here are found in temples all over the country. Tea and dinner sets, bowls with glasses, and table ware all also crafted here. The marble items, especially the table ware, are further embellished with minakari or enamelling. Jaisalmer, Nagaur, Sirohi, Udaipur, and Nathdwara are also important centres for the craft.

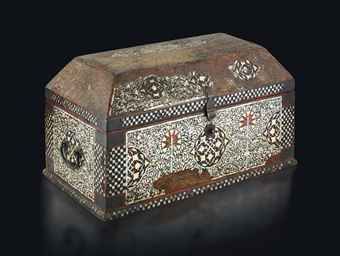

The craft of marquetry arrived from Iran to the land of Surat, Gujarat which is the hub of marquetry craft now. YThe patters fashioned by the craftsmen reveal the influence even today. It is locally recognised as 'sadeli'. The craft is used to decorate architectural structures, ritual objects of religious significance and other utility goods. Now today those craft is utilised in making small decorative goods that are often sold in handicraft or global markets, such as photo frames, side tables etc. The technique involves creating a patchwork of thin slices of wood veneer, inlaid with acrylic mosaic on the surface. The mosaics are constructed using basic geometric shapes. Originally ivory and rosewood were used for inlaying, but now acrylic is commonly used. [gallery ids="176673,176674,176675"]

The mashroo fabric has been woven in Kutch and Patan for many centuries. The word "mashroo" means "permitted" in Arabic and the craft has its origin in the prohibition By Islam on the use of silk. Mashroo is composed of a silk warp cotton weft. The ground material, which touches the skin is therefore cotton. The surface becomes smooth with the silk llater. Although mashroo was prevalent in other places, it survived as a craft only in Gujarat. Over the last couple of decades, silk has been changed to rayon because it's more easily procurable and cheaper than silk. The mashroo fabric is woven in a pit loom and with bright colours. The width of the fabric is narrow. Skirts, blouses, tunics for men and women are other garments made from the fabric of mashroo. Mashru fabric is a specialty of Gujarat. It exists in bright contrasting colors and is woven into many garments by the Kutchi community. which enlighten the sea of sand. The history of the textile revisits the traditional customs that were a part of the lifestyle of people living in Gujarat. It was originally worn by Muslim communities, who mixed the silk and cotton yarn to create this weaving style. This strategy was adopted as a solution to the aversion of wearing silk by the Muslim locals. Hence, weavers devised a solution where the lustre and softness of silk and transient comfort of cotton can be matched together for the locals in the Gujarat desert. The silk fabric appears to outside the garment while the cotton fabric is inside the garment. It makes mashru luxurious and imbues it with practical utility. The silk on the outer surface provides the gloss while the cotton in the back soak sweat and keep the wearer cool in the hot climate.

Odisha is well-known for crafting masks in wood, sholapith, and papier mache. These masks are used by the itinerant performers who stage plays based on the great epics. The wooden masks are usually made of light drift wood and then painted with bright colours. The craftspersons working with wood and papier mache are concentrated in and around Puri. Puppets with faces and limbs made of brightly painted wood and dressed in character are manipulated by string. They are popularly used in jatra, the folk theatre in Odisha.

With the tribal art and folk elements forming the base of Assamese culture, masks have found an important place in the cultural activities of the people. They have been widely used in folk theatres and bhaonas, with the materials ranging from terracotta and pith to metal, bamboo and wood.

In the bhaonas, masks are considered to be a must, especially for those playing the parts of mythological characters - Hanuman, Ravana, Garuda, and Jatayu, to name a few. Different materials are used in the make of these masks, varying from place to place. Similarly, among the tribal communities, the use of mask is varied and widespread, especially in their colourful dances, which again revolve chiefly around tribal myths and folklore. Such traditional masks have of late found their way to the modern-day urban drawing rooms as decorative items and wall-hangings, thus providing employment opportunities to the traditional makers.

Sri Lanka has abundant rush-ware and foliage plants, concentrated in the marshy lands of hinterland areas around villages on the southern coast of the country. Fibrous plants are found in the hilly regions. Mat-weaving is thus abundant. The craft is practised chiefly by women, often informally, while the men are away in the fields or in work-shops. Especially in rural areas, mat-weaving has been considered a skill that it is essential for girls to learn. Various varieties of rush-ware that are found include gatapan (Scirpus Erectus), pothukola (Scelria Oryzoides), galaha (Cyperus Corymbosus), tunhiriya, borupang (Eleocharis Plantaginea), hewan (Cyperus Dehiscens), and elupan. In Batticaloa and adjoining districts, a variety of rush known locally as kat-pan, probably the same as galaha, grows in abundance in the marshy areas and is widely used for mat-weaving. Galaha, used to make carpets, grows in Gampaha district in Ambalammulla. When mats were used only in the rural areas, the dyes were made of juices of leaves, fruits, and flowers from various trees. The red dye yielded by the patangi (Caesalpinia Sappan), is used prolifically and is the most important dye. To create black, the grasses are buried in the mud of rice-fields. The lower oxide of iron in the mud combines with tannin in the grass to form an inky black colour. Yellow dye is obtained from the young fruits of the kaha (Bixa Orellana) or from saffron, which is pounded in a mortar, and the extract boiled with water, for an hour, with the leaves to be dyed. Owing to an increase in the volume of mats being made, imported synthetic dyes are being used.

| PLANT | PART OF PLANT USED | |

| 1. | Pang | rushes/grasses |

| 2. | Galaha | rushes/grasses |

| 3. | Wetakeya | leaves of the foliage plant |

| 4. | Indikola | leaves of the palm |

| 5. | Palmyrah | pulp, sap, leaf, fibre, & timber of the palm |

| 6. | Talipot | leaves of the palm |

| 7. | Ekel | undried leaf fronds of the coconut tree |

| 8. | Savandara | roots of the plant |

| 9. | Hana | fibre |

| 10. | Navapatta | bark of the tree |

| 11. | Banana | fibre |

| 12. | Ornamental Coir | fibre obtained from the coconut husk |

- Ampara district: The pang craft is also found in the villages of Uhana, Adalachchena, Kalmunai, and Akkaraipattu.

- Anuradhapura district (about 270 kilometres from Colombo): Pang and galaha crafts are practised in all parts of the district.

- Galle district (about 150 kilometres from Colombo): The pang craft is found in the villages of Induruwa and Kaikawala; the galaha craft is found in the villages of Kaikawala and Athuruwella.

- Hambantota district (southernmost tip of the island): The pang craft is found in the villages of Mahahella, Ambala, Ranna, Walgameliya, Nalagama, Getamanna, Wagegoda, and Palankada.

- Kalutara district (south-western coast): The pang and galaha crafts are found in the villages of Paiyagala, Molligoda, Ittapana, Malamulla, Kalapugama, Maggona, Ihala Wadugoda, Kalamulla, Pothupitiya, Pohaddaramulla, Talpitiya, Walana, Nidelpitiya, Pinidiyamulla, and also in the town of Kalutara.

- Kurunegala district (about 130 kilometres from Colombo): The pang craft is found in the villages of Wewsirigama, Maweela, Kalahugama, Humbuluwa, and Alawwa.

- Matara district (southern coast): The pang craft is found in Kekanadure, Karaputugala, Kottegoda, Hittetiya, Deyagaha, Mee-ella, Galboda, and Walana.

- Polonnaruwa district: The pang craft is found in the villages of Palugasdamana, B.O.P. 314 and all the new settlements.

- Puttalam district (on the western cost): The pang craft is practised in the villages of Anamaduwa, Kammala North, Karavita, Divulwewa, Thattewa, Lunuwila, Kirimetiyana. Mahakumbukkadawala, Gurugodella, and Nattandiya.

- Ratnapura district: The galaha craft is found in the village of Kuruvita.

- Galle district (on the southern coast): The craft is practised in the villages of Kaikawala, Koggala, Induruwa, Kataluwa, Tirinagama, Habaraduwa, Narigama, and Welhengoda.

- Gampaha district (adjoining Colombo): The craft is practised in the villages of Pepaliyawala, Utwan Bogahawatta, Dompe, Weke, Waturugama, Mirigama, Pasyala, Keenadeniya, Ambepussa, Delwala, Mottunna, and Walarambe.

- Kalutara district (on the western coast, quite close to Colombo): The craft is practised in the villages of Pariyagala, Molligoda, Ittapana, Malamulla, Kalapugama, Maggona, Ihala Wadugoda, Kalamulla, Pothupitiya, Pohaddaramulla, Talpitiya, Walana, Nidelpitiya, and Pinidiyamulla.

- Kegalle district (close to Colombo; along the Colombo-Kandy route): The craft is practised in the villages of Ragalkanda and Mangedera.

- Kurunegala district (130 kilometres from Colombo): The craft is widely practised in the in the villages of Kolombagama, Udawela, Ambahera, Pannare, Alawwa, Pilessa, Weerapokuna, Wettewa, Narangoda, Nabirittawewa, Thorana, Hammalawagama, Wewala, Nugawela, Ratnegama, Vijayaudagama, Udakekulawala, Galature, Hettipola, and Siyambalagastenna.

- Moneragala district: The craft is practised in the village of Hingurukaduwa.

- Puttalam district (on the western coast): The craft is practised in the village of Botalegama.

- Ratnapura district: The craft is practised in the village of Kuragahawatta.

- Galle district: in Habaraduwa, Tirnagama, Hapugoda, and Narigama.

- Hambantota district (adjoining Matara district): in Netolpitiya village.

- Kalutara district (on the western coast): in the villages of Welipenna, Ihala Wadugoda, Padagoda, Ambepitiya, Horawala, Paiyagala, Walatara, and Sarikkamulla.

- Matara district (southern tip of the country): in the villages of Kirinda-magin-pahala and Udupeellegoda.

- Puttalam district: Wadigamanagawa.

- Ampara district (southeastern coast): in the villages of Kalmunai, Tirukkovil, Adalachchena, and Akaraipattu.

- Batticaloa district (eastern coast): in the villages of Puthukudiyirrupu, Koduwamadu, Kathiraveli, Eruvil, and Panichankeny.

- Hambantota district (southernmost tip of the island): in the villages of Labuhengoda and Chitragala.

- Jaffna district (northernmost tip of the island-country): in the villages of Thikkam, Puttur, Karaveddy, Chavakachcheri, Messalai, Kaithadi, Elavalai, Mandativu, Delft, Eluvativu, Velanai, Puloly West, and Alavai South.

- Kandy district (central part of the country): in the village of Madawala.

- Kegalle district (next to Colombo district): in the village of Mangadera.

- Kilinochchi district (in the northern part of the island): in the villages of Pooneriyan and Pallai.

- Mannar district (on the northwestern coast): in the villages of Erukkulampiddi, Pesalai, and Talaimannar.

- Mullaitivu district: in the villages of Puthukkudiyiruppu, Mathan, Thaniruttu, and Almit.

- Puttalam district (south of Mannar): in the villages of Kanaketiya, Illippadeniya, Wanathavillu, Serukele, Peramakkutuwa, Kirikattiya, and Sangattikulam.

- Gampaha district (next to Colombo): in the villages of Gampaha, Rideegala, Mirigama, and Kirindiwela,

- Kandy district (about 225 kilometres form Colombo): Ekel brooms are made in the villages of Kuragala and Kuragandeniya.

- Kegalle district (close to Colombo, on the route to Kandy): in the village of Galpatha.

- Kalutara district (south-western cost): in the villages of Pohaddaramulla, Waskaduwa, Talpitiya, Pothpitiya, and Kaluwamodara.

- Matara district (southern tip of the island): in the villages of Thamiliyaoula, Pelkiripitiya, Kotavila, Dandeniya, Muruthamure, Henegama, Palalla, and Alkgoda.

- Red is obtained by boiling the fibre with patangi (Caesalpinia Sappan) wood, korakaha (Memycylon Umbellatum) leaves, and gingelly oil and seeds.

- Yellow is obtained from a decoction of veni-vel (Coscinium Fenestratum).

- Black is obtained with the help of gall nuts, aralu, and bulu (Terminalia Chebula and T erminalia Beleria).

- Batticaloa district (on the eastern coast): in the villages of Kattankudi, Palamunai, Ollikulam, Kankeyan Oddai, Keechanpalam, and Paruthimunai.

- Kandy district (central part of the country): in the villages of Taldeniya and Udawala.

- Kegalle district (near Colombo, on the route to Kandy): in the villages of Badulupitiya and Devanagala.

- Kurunegala district (north of Colombo): in the villages of Kitalagama, Rambewa and Nikaweratiya.

- Matale district: in the village of Malhewa.

- Mullaitivu district (north of Vavuniya): in the villages of Vaddurakkal, Mulivakkal, Kanuvankum, and Kokuthoduvai.

- Nuwara eliya district (next to Kandy): in the village of Palle, Madanwala, Kotmale, Bowala, and Galauda.

- Puttalam district (on the western coast): in the village of Lunuwila.

- Ratnapura district (about 215 kilometres form Colombo): in the villages of Wikiliya and Belihuloya.

- Trincomalee district (on the north-eastern coast): in the village of Ralkuli.

- Vavuniya district (northern part of the country): in the villages of Annikulam, Madhukulam, Chalanpankulam, Nedukulam, and Kalmadhukulam.

- Colombo district: in the villages of Nawala and Kaduwala.

-

Kurunegala district: this craft is practised in the villages of Kitalagama, Rambewa, and Nikaweratiya.

- Kandy district: in the villages of Kuragala and Kuragandeniya.

- Galle district (southern part of the island-country): in the villages of Kalupe and Wataraka West.

- Gampaha district: Coir craft is also found in the villages of Eluwapitiya, Tarala, Getamaana, Uruwela, Batepola, Katunayake, Maduwegedera, Kitulawala, Attikehelgalla, and Galpotugoda.

- Kalutara district: in the villages of Pohaddaramulla, Waskaduwa, Narampitiyawa, Pothupitiya, and Panadura.

- Matara district (southernmost tip of the island): in the villages of Kamburugamuwa, Dikwella, Kolavenigama, Murutamure, Pahala Atureliya, Kottegoda, Waralla, Neelwella, Udupeellegoda, and Polwatumodera.

The thunga mats of Andhra Pradesh are made of thunga reeds woven artistically. They are made in and around Nellore and have geometric and floral patterns in attractive designs and colours. These mats are used in the home as floor coverings.

Mat-weaving is most commonly practised with kora grass in Karnataka. These mats have a cream surface and a bold border. The weaving process occurs in four steps: the splitting and drying of the fibre, its dyeing, the preparation of the warp, and finally the weaving and finishing.

The chitara community of Ahmedabad practices this craft. Kalamkari, locally known as matani pachhedi or devi-ka-parda, is made for the devotees of the goddess Durga. Kalamkari panels are first printed with wooden blocks and then painted wherever required. Maroon and black vegetable dyes are used against a background of white. The outline of the painting is in black and the main figure of Durga --- riding triumphantly in the centre ---- along with other epic scenes in done in maroon and white. Men usually outline of the paintings, while women fill in the elaborate details. Kalamkari products are used mainly as canopies over the images and are called chandaos.

Madur is the most popular of the mats made in West Bengal. It is woven mainly by the weavers of the mahishya caste in the southern parts of the district of Midnapore which covers the whole coastal area of West Bengal west of the river Ganga. The madur mat is woven on a simple bamboo frame-loom. The warp is cotton thread and the weft is a thin soft reed called madur kathi, which is cultivated in the Sabong, Ramnagar, Kholaberia, Sadirhat, and Narayan Chak in Midnapore district. The three types of madur mats of Midnapore are ek-rokha, do-rokha, and masland. Do-rukha has a double madur kathi weft, is thicker than the simple ek-rukha and is more comfortable to sit or lie on. Masland is a finely textured mat, which is made with carefully selected reeds. It has two borders of beautiful, geometrical designs, sometimes in a deep magenta but usually in self-colour, and the designs show up through the texture of the patterns. Muslim women of Ilamhaza in Birbhum district make palm-leaf mats with beautiful, geometrical designs in magenta, green, and blue. They use deft calculations and arrange the narrow strips to form parts of a broad design that fits in beautifully as the strips are joined together to form a whole mat. Large chatai mats are made from the fan-shaped leaves of the palmyra palm. These are woven with the flat strips of the leaves as both warp and weft. They are made and used extensively in Birbhum, Bankura, and Purulia districts. Shitalpati mats are made from mutra cane grown mainly in the Cooch Behar district. The baskets of West Bengal are chiefly made out of bamboo; the other materials used are certain varieties of grasses, straws, and palmyra leaves. Baskets are either plaited or coiled. In plaited basketry the warp and weft are made to interweave in various ways. When the warp and the weft pass over each other singly, a check weave is obtained. When each weft passes over two warps and goes under two, the weave gives a twill effect. From the basic weaves, hundreds of weaving patterns have evolved. Besides bamboo, coiled baskets are also made with a tall flowering grass called kash or keshe. Keshe and other straw baskets are made by rural Muslims. The tall keshe grass blades are spliced together to form a rope-like core material as thick as a pencil. The basket is built up of a continuous spiral of the core material from the base upwards, stitched together in different patterns with binder materials like the skin of some creeper or the strong rib of the date-palm leaves. The shape of the basket is determined by the way the spiral is let out from the foundation. Basketry in West Bengal is practised by members of the lowest caste or community known as doms, namasudras, and bagdis, along with poor Muslims and tribal people who live in the hills and forest areas and at the periphery of larger village communities. The crafts are pursued to meet the needs of the poor; basketry is a family craft and a community activity.