Sabai Grass (Botanical name: Eulaliopsis binata Family: Poaceae ( Grass Family) is a tufted perennial grass with basal sheaths woolly with whitish hairs. Locally the fibre or the grass is called Babui Ghash. The grass grows in abundance in the forest fringe areas of Purulia, Bankura and Paschim Medinipore. The Grass is collected by the women and after proper washing and drying the grass is twisted in bundles to form ropes. The Main livelihood is making of ropes and selling it at the local market. Sabai grass is also used in the paper industry. but many artists also make various Sabai based diversified product which has a market at local. Sabai grass is abundant in some pockets of Paschim Medinipur, Purulia and Bankura districts, Around 4000 artists are involved with Sabai Craft in the region.

Process: The grass is first cut and thrashed on the floor properly, to make it soft and easy to be twisted. the next step is to soak the grass in water and keep it for drying. After drying of the grass, they twist it in bundles to form ropes. The ropes are also made through a wheel twisting machine. One operates the machine and another one holds the rope from other side. the ropes formed have rough edges which is then removed after rubbing it on the branches of the trees to remove the extra edges and to make it smooth. Lastly they make the bundle of ropes of about 250 gm, 500 gm and 1 kg. For making Sabai based products the grass is twisted to actually give shape to a product and dead palm leaf is used to bind the same and also add a proper texture to the product. For many products frames are required to actually give shape to the product. the weave is done around the frame. such frames can be used for floor mats, bags, flower vase etc. The grass and the ropes are also dyed to give colours to different products.The Buddhist sacred paintings, the thangkas, that originated in Tibet, are renowned the world over; the Nepalese paubhas influenced by ancient Hindu sacred paintings and texts are relatively lesser known. Both thangkas and paubhas are valued not only as objects of meditation and worship but also as works of art. Painting has occupied a special position among the arts and crafts of Nepal and has served as a medium for expressing religious beliefs in worship. The art of painting grew along with metal iconography as an important form through which the highest ideals of Buddhism and Hinduism were brought alive and evoked. Sacred paintings, such as the paubha or thangka, were commissioned, worshipped, and cherished. These sacred paintings illuminating a deity or event, usually of a religious nature, are depicted on a scroll of cotton or silk cloth that is beautifully mounted on a brocade fabric. On completion of a sacred painting the ritual for merit dedication is followed, inspired by a desire to attain enlightenment. Prayers are made which place a final seal on the meritorious act, which accrued to the ultimate attainment of enlightenment. This, it is believed guarantees that the meritorious deed will bear the highest and most lasting fruit. The painting of thangkas in Nepal is an ancient tradition. The Tibetan exodus further led to their proliferation, with a number of shops in Katmandu Valley beginning to sell them. As sacred paintings they were not supposed to be sold; however, as there was a great demand for them they were painted for sale and were available in the market. The thangkas no longer need to be commissioned and can be bought off the shelf - however thangkas bought of the shelf have to be consecrated to a deity before they can be worshipped.

- Stretching the canvas on a wooden frame

- Preparing the painting surface

- Creating the design or composition by sketching or by what is called 'transfer' or tracing

- Laying down the initial coats of paint

- The principal application of paints

- Adding the finishing touches.

- Filling in the areas with different base colours; and

- The subsequent shading and outlining of these areas.

The sadu bharat stitch is recognised by long satin stitch and running stitch covering the entire fabric surface. It is done with staple bright colours. Like the ahir embroidery, this stitch comprises making use of mirrors to get a glimmering effect. The threads used for stitch contrast the base fabric. The 'bavaliyo' stitch, created by twinning the threads and filling it on the surface without piercing the needle on the reverse side of the fabric is extensively used in Sadu Bharat embroidery. A range of products including garments, interior decors, etc is produced using this stitch from Gujarat. [gallery ids="178014,178015,178016"]

The saree is a traditional garment all over India, and is worn in different styles depending on the region and occasion. The silk sarees of Salem are renowned for their intricate workmanship and the use of zari, which adds value to the product. Elampillai in Salem district is one of the largest manufacturers of silk sarees in Tamil Nadu. With the changing times, many artisans have started making cotton sarees as well. The major community involved with the weaving is the Vanniyar. Silk sarees are sent to the Tirupathi temple to be used as attires for the deities during different ceremonies.

The white silk dhoti of Salem in Tamil Nadu is a special variety of handloom products from this area. Pure mulberry silk, normally obtained from Karnataka (Bengaluru and Mysore), is used in the warp and weft. Pure zari or “half fine” (imitation zari) is used in the border, which is unique to this range. The silk dhoties are famous for their lustre, whiteness, technical excellence and novelty of the border designs. They are woven on pit looms/raised pit looms. The border design in extra warp is woven with the help of the lattice dobby.

Sandalwood-carving is done with a lot of precision and is considered to be an auspicious job given its scarcity and high value, its fragrance. Sandal wood carving involves intricate detailing as the pieces are not large of length and require assembling if made in large size with the articles invariably carved with extremely elaborate patterns consisting of interlacing of foliage and scroll work. The products include miniature and larger size models of the Taj Mahal, Qutab Minar and other monuments, ships, chariots, photo frames, mirror frames, key chains etc

Sandalwood carving is the craft that the ivory carvers of Delhi turned to with the ban on ivory in 1989. Sandalwood carried a special aura and was the choice of raw material that the carvers turned too using simple yet fine tools that include chisels/ Kattra, files/Reti, vice, hammers and aari/ saw

Only about five to seven craftsmen practicing this craft in Delhi and are located in Sitaram Gali and Sheesh Mahal Bazaar in Old Delhi.

Besides being one of the oldest fragrances known to man, sandal wood is of great religious significance and is a highly prized material for carving artefacts. As the sandal wood tree grows, the essential oil develops in the roots and heart wood, lubricating the tree's core with its softly exotic perfume. Karnataka has a huge forest-belt and sandal wood carvers are found in Bangalore, Mysore, Shimoga, Sorab in the foothills to Sirsi, and Honavar and Kumta on the coast. Sandal wood is of two types: srigandha which is close grained and yellowish-brown in colour and used for carving; and nagagandha which is darkish-brown in colour and from which oil is extracted. The sandal wood tree is never felled; it is, instead, uprooted during the rainy season when the roots are richer in oil. The wood is refined and used to make a plethora of products that range from idols of deities and finely wrought chariots to decorative pieces such as paper cutters, boxes, name cases, trays, photo frames, combs, walking-sticks, fans, cigarette cases, holders, and the ever popular elephant. Jali or fret work with patterns in high and low relief are also popular. The wood is refined, smoothened and cut into pieces of the desired shape. Then designs are carved out in it with chisels and the finished piece is polished with sandpaper.

Sandal wood is used extensively to make religious images, figures in traditional costumes, and animals (mainly the elephant) in the same centres where rose wood carving is done.

These are made from the sandalwood shavings, which are shaped and strung on string in particular patterns to form the garlands. These are made in Mysore, Sagar, Sirsi and Kumta districts of Karnataka. The shavings are left in their natural form with no painting or any other form of embellishment.

The garlands of Tamil Nadu are well known for their imaginative arrangement and juxtaposition of colours. This is a traditional craft. Arali buds and flowers are collected and woven into garlands for decorating deities in temples on festive and auspicious occasions. The craft requires patience, skill and imagination. In addition to the traditional garlands, the craft is also used to make unusual temple decorations. Sandalwood Garlands are made from the sandalwood shavings, which are shaped and strung on string in particular patterns to form the garlands. These are made in Mysore, Sagar, Sirsi and Kumta districts of Karnataka. The shavings are left in their natural form with no painting or any other form of embellishment.

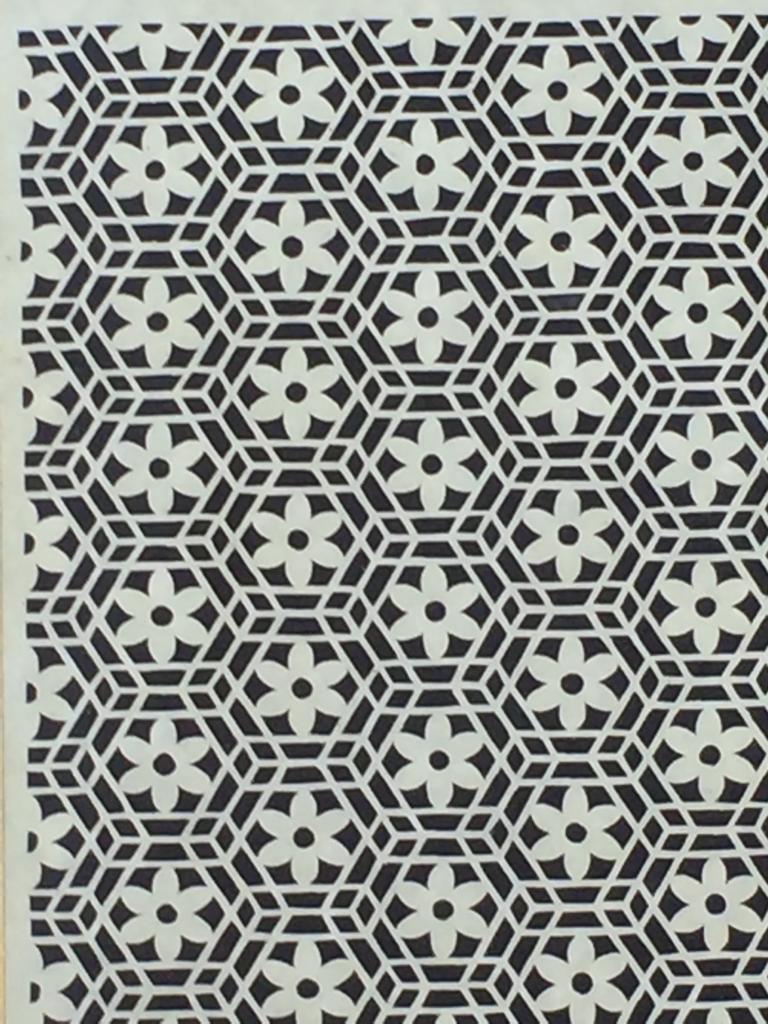

Sanjhi- the hand-cutting of paper for ritualistic and ceremonial rangolis - is commonly understood in its contemporary form as a ritualistic craft used in temples, and sometimes homes, for the worship of Lord Krishna. It is believed to have originated, according to the thesis forwarded by Asimakrishna Dasa, in his book Evening Blossoms: The Temple Tradition of Sanjhi in Vrindavana, as 'a ritual worship undertaken by unmarried girls all over northern India to obtain a suitable husband'. Thus, while the temple craft is practised only by male priests and their male apprentices, the folk aspect of the craft was, and is, practised chiefly by unmarried girls.

This craft, which involves the cutting of an intricate stencil depicting scenes from the life of Lord Krishna and the use of this paper stencil in creating a rangoli or floor decoration, became a temple tradition (according to Dasa) in the 17th century, 'when the devotional bhakti movement linked it to games played by Radha and the Hindu god, Krishna. While the ritual of sanjhi, in its devotional and decorative aspects, continues in villages and homes in north India, the temple tradition seems to have become confined to three important temples at Vrindavana and a single temple at Barsana, Radha's village.

It is important to remember that all sanjhis, whether a part of the folk tradition or of the temple tradition, are made to be worshipped. According to Dasa: "At the time of worship they are transformed from works of art fashioned by human beings into a divine being, Goddess Sanjhi... the transformation from design to goddess comes about naturally with the offering of food bhoga followed by ritual worship aarti performed with burning wick and an offering of water.'" This explains the fact that effacing each sanjhi the next day and painstakingly beginning to create another one is seen not as tedium but a labour of love, 'to please Lord Krsna'

Presently the art of using the sanjhi is practiced mainly in the temples and homes in Vrindavana in Uttar Pradesh and it is used to depict the different episodes in Lord Krishna's life; these episodes are linked to festivals in the Vraja calendar. The most important of these festivals is the vrajayatra, a period of 45 days in September and October when pilgrims from all over India visit the sites associated with the life of Lord Krishna. During this period sanjhis are used to decorate specific locations and places along the parikrama. The episodes in Lord Krishna's life that are depicted through sanjhis change every day, with appropriate themes adorning specific locations. For instance, at Govardhan the traditional sanjhi is one that will depict Lord Krishna lifting the mountain with his finger. At Barsana, the sanjhi depicts Lord Krishna playing Holi with Radha and the gopis. When the sanjhi is unveiled in time for the evening prayers it is worshipped to the accompaniment of songs narrating stories about Lord Krishna's life. The sanjhi is effaced in the morning and a new characterisation is then made. At the end of the pitr-paksha, a fortnight when Hindus perform rites for and offer prayers to deceased ancestors - when sanjhis are ceremonial - the materials used are then disposed off in the river Yamuna.

Originating in Mathura, Sanjhi or paper stencil craft is produced in the region of Alwar. The method involves cutting out intricate patterns drawn on various types of paper and then using the stencils to create designs with flowers or powdered colors. Tools such as knife and scissors are used for the crafting process.

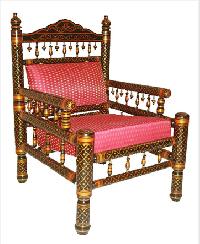

Sankheda furniture is a common sight in most of the traditional Gujarati households. This furniture made in the town of Sankheda has unique patterns and designs. They are made from teak wood and treated with lacquer. They are painted with traditional bright shades of maroon, yellow and gold. To compete with today's demand for different modern colours, Sankheda furniture is now also coloured in ivory, burgundy, blue, green,copper, etc. The hichako (swing) and the ghodiyun (child's cradle) are most popular furniture pieces of Gujarat.

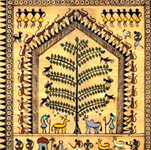

Saora folk painting is a type of mural painting native to tribal areas of Odisha. Their wall paintings are known as ‘italons’ or ‘ikons’. These ikons have variety of figures ranging from humans, horse, and elephant to aeroplane, cycle, sun, moon, etc. These paintings and figures are ritualistic in nature and have assoications with divinity and religion. These paintings are easy to make, but difficult to understand as all paintings convey a different message. Usually these paintings are made in a rectangular or square format or in the shape of a hut enclosed with decorative borders of geometrical shapes. The paintings are usually done with a red background. The materials required for the paintings are also simple and made from locally available material like red is extracted from red clay, white is extracted from chalk or lime. With the passage of time and commercialization, the medium for Saora painting also changed. They shifted their canvas of mud walls of their houses to wooden frames, paper and various other commercial mediums like textiles, crockery, etc. The art of the Sauras a tribe based in Orissa, draws inspiration and direction from their spiritual and religious beliefs. It functions as a means of worship and a medium of invocation. Over the centuries, the Sauras have developed an elaborate system of sacrifices and procedures involving magic, incantation, charm and sorcery intended to compliment and offer praise to the spirits thereby appeasing them. One such practices is that of painting on the walls of their homes as these spaces serve as temporal resting spaces in the living world for the spirits. Their arts create a consecrated space within domestic dwellings. This tightly knit world of people and spirits is the base of saura Art. The artist rendering the artwork is directed by the shaman or may get possessed himself when invoking the spirits to guide his hand. Using fresh red earth and water to provide a good background the painter uses a twig as a brush. The main colour - white is usually sourced from rice, ash, chalk or lime mixed with water, with lamp black, red ochre, indigo blue and yellow also used. The stylistic variation can be grouped in four categories. Each group is identified with the village that is centrally located in the area and the style is named after the village Puttasingh, Padampur (Koraput district) Seranga and Mohana (Ganjam district)

In addition to fine cloth, satranjis a floor rug, made from a mixture of jute and cotton yarn, is woven on a simple horizontal loom made from bamboo and jute string in Nisbetganj. A vertical loom is set up in a weaver's home for tapestry or rug making. The reed or shana is generally made from wood and wire or string whereas the maku or shuttle is made from wood. Other implements required for processing the yarn include a natai and charkha for winding the yarn, a nail or bobbin.

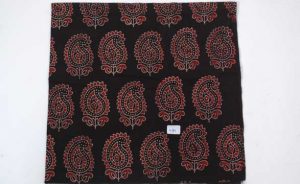

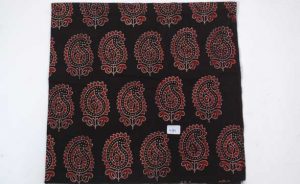

The saudagiri printed fabric is quilted with a running stitch. It is massively exported from the central location of production Ahemedabad, to markets in Southeast Asia. Multiple hand block techniques are used to create Saudagiri textiles. They are often characterised by repeated geometric prints, floral and faunal motifs. These motifs were usually inspired from the nature of Gujarat and the most sytlise dones were of the peacock, parrot and goose figures.

These are mainly made in Varigonda village in Nellore district and Vemulavada and Nupuram villages in East Godavari district. These toys feature traditional themes and historical figures from Hindu epics.

The products made with screw pine include table mats, floor mats, cushion covers, coasters, bags, box covers, beach hats, handbags and wall hangings. The mats are often embellished with fine hand embroidery. The two-ply screw pine mats, used for sleeping, consist of a fine upper layer and a coarse bottom one, with stitching at the edges. Superfine mats are made from very fine screw pine leaf splints placed 8 to 10 per inch. High quality mats of up to 22 splints per inch can also be made by experienced artisans. Cleaned leaves are split in half without disturbing their original length. The long and narrow leaves are boiled and then placed in fresh water overnight. The leaves are dried, and after a couple of days they become ivory in colour. Once dry, the leaf is straightened with a knife and kept rolled and bundled until the weaving begins. The weaving is done with one weft leaf going diagonally between two warp leaves.

Printed in earth colours, this is a traditional craft practised mainly at Cherial in Warangal district. The art form is believed to have come down from Vishwakarma, the divine architect of the artisans, and has stood the test of time over generations. The technique of painting is traditional and the themes are derived from Indian mythology. Cheriyal Paintings are beautiful works of art that are painted on khadi or cotton cloth. The richly coloured paintings depict the Hindu epics in a narrative format. Initially, these paintings were done only on scrolls running into many metres (about 10 to 30 metres) in length. Presently, they are done on small pieces of khadi or cotton cloth or even on cardboard. Various items such as masks, marriage gifts, jewellery boxes, brass paintings and greeting cards are also decorated with these paintings. This type of painting is a community based art; the Kaki Padagollu is the main community and they use the paintings as a visual aid to recite tales from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Cheriyal Paintings are typically characterized by their size, which can be many metres in length, and the background that is painted mainly in a red colour. They depict tales narrated by different communities.