Paatra, the lightweight bowls, are produced for the monks of the Shwetambar Jain and Vaishnav sect. Items such as large wooden plates, utensils for Jain and Vaishnav monks, bowls, boxes, rolling platform and pin, wooden pegs for walls, handles for tools are produced under this craft-form. Tools such as lathe, hand drill, chisels and files are employed for crafting purposes.

Products ranging from Paabu, Kir-paabu, Thigma-paabu, boots worn by monks during ritual dances etc are made under this craft. Tools needed for the process are needle.

The marble tomb of Shaikh Salim Chisti in Fatehpur Sikri was built in 1572 by Emperor Akbar. It is the precursor to an age known as the 'Reign of Marble' for, with the accession of Emperor Jahangir, sand stone gave way to marble, the crafting of which peaked during the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan with the building of the Taj Mahal in Agra. Marble was used not only in building but also in other ways. Craftspersons used it in mosaic patterns combined with red sand stone and other colours of marble and embedded it in cement. They used marble to make intricate jaalis (perforate relief) that filtered light and they used it most exquisitely for inlay work or pietra dura. Here precious and semi-precious stones, jasper, cornelian, topaz, mother of pearl, turquoise, lapis lazuli, coral, jade, agate, and porphyry were shaped and set in shallow chases carved in the marble. The most frequently used decorative motif was the arabesque, the ornamentation being in a stylised floral form with geometric interlocking. Since the time of Shah Jahan, Agra in Uttar Pradesh has remained a thriving centre for marble work, including inlay. The marble is obtained from Makrana and the semi-precious stones come from all over the world. The artisans of today fashion vases, coasters, table tops, boxes, plates, and trays, models of the Taj Mahal, lamp bases, flooring, fountains, chairs, water basins, chess sets, and hookah stands. The process followed in pietra dura is complex. Here the semi-precious stones are first sliced finely with a bow of tensed steel wire --- the process in slow as it can take up to an hour to cut through an inch of stone. The stone is then washed and cut into smaller pieces to facilitate the intricate and minute shaping required. The shaping of the stone is done against a rotating disc. The artisan works the disc with his right hand and holds the stone in his left hand. When each minutely shaped piece is ready it is placed in its designated position on the marble surface. The outline of the pattern is then defined with a sharply pointed instrument. The stone is then pressed into place and fixed with a burning charcoal. If the whole process has been executed finely there should be no line of cement visible between the inlaid stone and the marble. The final polishing is done with zinc power.

Of the painted variety of pottery, the most popular are colourful containers called shokher hari, used for weddings and other festive occasions. Decorated with birds, fish or floral motifs drawn in bold sweeping lines, these pitchers are painted in brilliant hues of red, blue, green and yellow. They have a symbolic significance for Hindus and are also known as mangal ghat. The ritual sara, the painted convex earthenware plate is unique. Normally used to cover wide mouthed pottery vessels, the village artisan uses this simple article as an inexpensive alternative to the larger images which are worshiped during Hindu festivals and later immersed in the rivers. The circular convex shape lends itself beautifully to an illusion of wider dimension. The convex shape of plate is said to represent the delta of Bangladesh which rose from the waters, with the rimmed edge signifying the embankment. Sectionalised to incorporate the ancillary subjects drawn from related myths, the principal god or goddess occupies the central panel. The figures are drawn in bold clear lines reminiscent of the drawings of pat paintings and coloured in the same vivid shades as the shokher hari. Often referred to as Lakshmi sara, these charming plates may depict Lakshmi, the goddess of fortune, standing on a mayurpankhi (peacock shaped) vessel on the Lotus Lake, or on the sacred owl. Images of Durga and her lion, destroying the buffalo demon, or Radha and Krishna, are also depicted on these ritual pot covers. In painted pottery, the red colour used is red lead, yellow is arsenic, green is a mixture of yellow arsenic and indigo, black is produced with lamp black made from charred rice seeds. These colours are mixed with a mucilage prepared from tamarind seeds or the gum of the bael (aegle marmelos) before application.

The painted terracotta of Gujarat is unique for the dramatic impact made by the deep, rich terracotta base colour combined with the minimalistic pattern painted on it in stark black and white. Less than a handful of artisans practise this craft that is unique to Gujarat. The pots are shaped by the men on the wheel; other shapes, mainly toys are also hand-moulded by the men. The painting is done by the women of the family, while the pots rotate on an improvised pivot. Resembling embroidery, these lines and motifs create rich and intricately designed pottery. Only a handful number of artists practice this age-old craft of hand painted terracotta in Kutch and Surendranagar. Wares are made using locally available clay on the wheel and the ornamentation is carried out by the womenfolk. Base coat is created using a dark terracotta colored slip of watered down geru, red clay and then patterns are created in black and white using bamboo stick brushes. Wares such as water pots called maatlo, money boxes called gallo and pots etc are created.

This craft is practised only by a few artisans from the Kutch and Surendranagar regions of Gujarat including Hasam Umar Kumbhar and his wife Amina Hasam Kumbhar who are both National Award winners and whose creations include pots, toys, diyas, mobiles, plates and bowls. This technique of decorating pots is not practised at any other location in India.

This craft is practised only by a few artisans from the Kutch and Surendranagar regions of Gujarat including Hasam Umar Kumbhar and his wife Amina Hasam Kumbhar who are both National Award winners and whose creations include pots, toys, diyas, mobiles, plates and bowls. This technique of decorating pots is not practised at any other location in India. products are dried once again in the sun. The painting on the pots and toys is done only by the women. A dramatic combination of black and white - also obtained clay - is used,. The clay is mixed with water to achieve the required consistency and the designs are painted on the pots with the help of a twig. These brushes of bamboo sticks are sharpened at one end and beaten to form a brush-like end. The article to be painted is rotated either on a pivot or manually on another pot. The skill shown by Aminaben as she manipulates the pot with one hand and the ease with which a blemishless design is transferred on the pot with the other hand is fascinating.

products are dried once again in the sun. The painting on the pots and toys is done only by the women. A dramatic combination of black and white - also obtained clay - is used,. The clay is mixed with water to achieve the required consistency and the designs are painted on the pots with the help of a twig. These brushes of bamboo sticks are sharpened at one end and beaten to form a brush-like end. The article to be painted is rotated either on a pivot or manually on another pot. The skill shown by Aminaben as she manipulates the pot with one hand and the ease with which a blemishless design is transferred on the pot with the other hand is fascinating. The designs are mainly geometric patterns of dots, lines that are vertical, horizontal and diagonal, squares, and loops, along with figurative motifs of humans, birds, animals, plants scorpion, fish, flower and herringbone. These are drawn by hand between the bands. As the pot is rotated by hand and the point of the twig dipped in colours is held against it, the designs appear as if by magic as the pot moves. Once the designs are complete, the articles are fired. The shape of the vessel and the community for whom the pot is intended determine the designs painted on. The pot is divided by horizontal bands between which the design is laid. The artisans are careful about this process, at this has to happen at the right degree to give the desired appearance.

The designs are mainly geometric patterns of dots, lines that are vertical, horizontal and diagonal, squares, and loops, along with figurative motifs of humans, birds, animals, plants scorpion, fish, flower and herringbone. These are drawn by hand between the bands. As the pot is rotated by hand and the point of the twig dipped in colours is held against it, the designs appear as if by magic as the pot moves. Once the designs are complete, the articles are fired. The shape of the vessel and the community for whom the pot is intended determine the designs painted on. The pot is divided by horizontal bands between which the design is laid. The artisans are careful about this process, at this has to happen at the right degree to give the desired appearance.The rich colors of painted woodwork provide a relief from the desolate landscape of Ladakh. Production clusters center around Leh. Items such as folding tables called choktse, window frames, furniture panels,architectural panels,giant drums and prayer wheels are painted using multitudes of shades and colors using paintbrushes.

Painting in Bhutan encompasses:

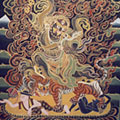

- Religious paintings: In the form of murals, thangkhas and manuscript illustrations. These are done by artists who follow a certain uniform style in creating what are not works of art but of faith - which they make as beautiful as possible, while scrupulously following the precise and symbolic iconometric and iconographic rules codified in ancient treatises. The act of commissioning and creating a religious painting is seen as a pious act that earns great merit and must be done with a pure mind.

- Decorations on furniture and window-frames: Nearly every house and building is colourfully painted with symbols such as a lotus, a dragon or the Tashi-Tagye as are furniture, tables and many objects that are a part of the daily lives of the people.

- Murals

- Thangkhas

- Manuscript illustrations

- Murals in Dzongs and Monasteries The dzongs, monasteries and temples contain incredibly beautiful works of art. Within their massive stone walls and measured wooden beams are found paintings representing important religious figures and mandalas, and narrative paintings portraying events in the life of a saint or other life stories. Many intricate and colourful illustrations serve as allegories, dramatising the continuing struggle between good and evil.

- Thangkhas Thangkhas are painted scrolls found in monasteries, using tantric symbols and natural phenomena such as water, fire and animal life. Since Bhutanese art is to serve primarily as a visual aid for understanding the tenets of Buddhist philosophy, a shrine could have one or more thangkhas. The themes of a thangkhas could be the Buddha; Guru Rimpoche; Tara; Wajra Kila-Phurpa; Sidpa Khorlo or the six realms of existence (God, demi-god, human life, animal life, hell and hungry ghost); Zambala, the God of health; Amitause, the God of Long life; Avlokisteshwara, or the God of Compassion.

- Manuscripts - Calligraphy In the past calligraphy has been practised as a fine art in Bhutan. Beautifully written manuscripts on separate sheets of centuries old handmade paper can still be seen in a surprisingly well-preserved state. Depending upon the nature of the text, the manuscripts also contain miniature paintings.The great importance given to books is reflected in the care that goes into writing and making them. Certain texts are written in calligraphy with ink made from gold dust and illuminated like medieval manuscripts in Europe. When the printing or calligraphy of a whole text is completed, the pages are bound between two wooden boards. The upper board may be a work of art in itself because it is often carved with religious subjects and perhaps covered with a sheet of wrought, gilded copper.

- The Buddha in many forms

- Guru Rimpoche or the eight manifestations of Guru Padmasambhava - the great saint, who arrived in Bhutan in the year 800 AD.

- The 21 Taras

- Wajra Kila-Phurpa

- Sidpa Khorlo or the six realms of existence - God, demi-god, human life, animal life, hell and hungry ghost. The Wheel of Existence shows the six spheres of existence within which the sorrowful lives of non-enlightened beings take place. It is found hanging in temples as a meditational picture.

- The Wheel of Existence whose six different sections illustrate the world's unreality to which every living being in this world is inextricably bound. The cycle of births and death, caused by human ignorance, is enacted here in all its sorrows and pains until finally it points to a path of salvation.

- Zambala, the God of health; Amitause, the God of Long life; and Avlokisteshwara, the God of Compassion

- The Tashi Tagye or the eight auspicious signs which are intimately associated with the life and teachings of the Buddha (refer article on Symbolism in Bhutanese Art).

- A mandala or khyilkhor - a sacred, cosmic diagram representing the universe. The mandala is basically a mystical pattern used for purposes of initiations and meditations. It was introduced in Bhutan together with all the teachings and methods of the Buddhist tradition, and its complex geometrical patterns are to be seen all over the country in a multiplicity of arrangements.

|

|

|

|

- Canvas

- Wooden frame for the stretched canvas (The sides of the canvas are folded and stretched with cords to make it stronger and properly stretched.)

- Brushes of animal hair

- Paints: Made from carefully selected mineral sources - mineral pigments have to mixed with the size binder and the pigments themselves to produce another colour. (Size is actually a glue made out of skin of animals / leather boiled and dissolved. It is turned into gelatin. The size or binder is added to the pigments until it becomes a thick homogeneous liquid - the ideal consistency being like buttermilk. Traditional pigments are widely used but are more expensive than chemical paints. The colours used in Bhutan seem to be both organic and inorganic: cochineal for red, lapis lazuli for blue, arsenic for yellow and a mixture of arsenic with lapis lazuli in different proportions to produce greens in a variety of shades.

- Mild for the bodhisatvas;

- Slightly stronger for tutelary images and other creatures; and

- Bold dark colours like black and blue for the terrifying deities.

- Buddha

- Peaceful boddhisatvas

- Goddesses

- Tall wrathful figures

- Short wrathful figures

- Humans

- Usage of pigments of bad quality.

- Lack of details in the background and on robes of deities.

- Disregard for proportion in the basic drawing.

- Inappropriate colours, tones and subject matter.

- The over use of shading in faces of deities.

- Improper stitching of the brocade frame.

-

Style of Painting: The main difference between a quality thangkha and a commercial one is in terms of proportion. In a quality thangkha the dimensions are perfect and correspond accurately to instructions given in the sutras (Buddhist texts)

Quality paintings in most cases are shaded in 'Kamdang' style (dry shading), while commercial thangkhas are shaded in 'Lemdang' style (wet shading). 'Kamdang' can be clearly identified as small horizontal strokes of paint in the sky and on the hills, and as small soft dots of colour on clouds and flowers. It is a long procedure where a square inch of area could take perhaps a day to be filled. Lemdang can be identified as a smooth gradation of colour and is quickly accomplished. The outline of the eyes, face, fingers, and feet in quality thangkhas are detailed, accurate and perfect. The commercial paintings will not have such details. The halo of the deities for quality thangkha painting will have a perfect circle whereas some irregularities can often be found in commercial paintings. The gold decoration on the painted surface of a quality thangkha will shine when tilted against light whereas the artificial gold on a commercial thangkha will not. - Duration: An average quality painting could take many months or even years of continuous daily labour, whereas the same subject matter in a commercial thangkha could be completed in 2 to 14 days.

- Brocades Frames: On a quality thangkha the back of the canvas will be exposed and a mantra written on it. The plain cloth covering on the sides of the back part of the brocade will be stitched manually on to the edges of the thangkha itself. The outer silk cover will have another colour of silk at the sides that are slightly overlapped. There will be a pair of carved rings hooked against the top bar to hold it upright. The top ends need to be stitched with leather protection squares on the back. The 'toke' or the knobs at the bottom ends will be carved silver with gold gilding. The silk cloth will be of the highest quality possible and sewn with accurate straight stitches following the rules of proportion. The corners of the brocades must have a perfect angle and the painting must hang straight.A commercial thangkha painting will probably be covered by a single yellow piece of cloth. The backside of the painting could be covered entirely by plain cotton without mantras. The painting could be decorated with artificial gold designs. The top will probably be plain with no hooks or rings. The knobs could be of cheap metal only and most probably the stitching will be not straight.

- Rates: A commercial thangkha painting may cost Nu. 1,500 upwards. A quality thangkha can cost a minimum of Nu. 15,000.

Tangkha paintings are religious scroll paintings which depict Buddha and his preaching. These paintings are also an important tool to teach Buddhism primarily displayed in monasteries. The display of Tangkha signifies a great dedication towards the religion and self reliance to achieve salvation. The painting is prevalent in the Buddhist dominated regions of Tawang, West kameng, Upper Siang Districts of Arunachal Pradesh. The Tangkha is Kuthang in local terminology of the Monpas of Arunachal Pradesh. It is regarded as an object of worshipping which is primarily been displayed in the monasteries, Gompas (Buddhist temples) and Lhagang i.e. family chapels. The meditation and worships in front of the Tangkha and the sculptures indicates right way for self purification and get protection from all evil motifs. Besides, the display of these holistic materials compensates peace and tranquilities amongst all living beings. The belief amongst the Buddhists is to pay heed, to preserve and display Tangkha and sculptures in the holy-shrines for offering worships and prayers. Thus, the importance of Tangkha and sculpture amongst the Buddhists of Tibetan Mahayana sect are narrated in the literature.

The tradition of paintings in Assam can be traced back several centuries. The gifts presented to the Chinese traveller, Hiuen Tsang, and to Harshavardhana by Kumar Bhaskara, the king of Kamrupa, included a number of paintings and painted objects, some of which were done on exclusive Assam Silk. Assamese literature of the medieval period contains references to chitrakars and patuas who were expert painters, They used various locally available materials like hengool and haital. A large number of manuscripts of that time have excellent paintings in them, some of the most famous being Hastividyarnava (A Treatise on Elephants), Chitra Bhagavata, and Gita Govinda. Assamese palaces and naam-ghara still display brightly coloured paintings depicting various stories and events from history and mythology. In fact, the motifs and designs contained in Chitra Bhagavata have been adopted as the traditional style for Assamese painting and are visible even today.

Paithan (near Aurungabad) in Maharashtra is the home of the paithan sari, an extremely rich silk and zari sari. This traditional sari also represents a very old weaving tradition. An inscription in the Sun Temple at Mandsaur in Madhya Pradesh mentions paithani weavers. The Maratha Peshwas had a special love for this fabric. The paithani was extremely popular during Peshwa rule in Maharashtra, a time when it received sustained royal patronage. (At this time, the yardage was also used for stitched garments). There are records of a Peshwa king in the seventeenth century asking his Prime Minister Nana Phadnavis to send him paithani garments and, in the nineteenth century, of the Nizam of Hyderabad ordering it for his wife.

-

Field: The traditional paithani has a coloured silk (sometimes cotton) field; 'the field contains a fair amount of supplementary zari patterning'. The field is now commonly woven of pure silk; earlier, silk and metal (gold thread) end-panels (pallus) and borders were sometimes woven separately and attached to fabrics of pure cotton.

-

Borders: 'The borders are created using the interlocked-weft technique, either with coloured silks or zari'. 'A wide band of supplementary warp zari (in a mat pattern) is woven upon the coloured silk border. In borders woven with a zari ground, coloured silk patterns are added as a supplementary-weft "inlay" against the zari....'

-

Endpiece: The end-piece has 'fine silk warp threads...[and] the weft threads are only of zari, forming a "golden" ground upon which angular, brightly coloured silk designs are woven in the interlocked-weft technique, producing a tapestry effect.'

Universally as familiar in Nepal as the rari, the soft woven wool pakhi is indispensable in the colder regions. The Pakhi, softer than the rari in its construction, is woven in the northern part of Nepal. It is used as an outer covering as well as the base material for clothing items like the ghala, namja, panki, and kiri. The pakhi is worn and woven mainly in the Himalayan foot-hills. Its warmth protects the body from the biting cold and winds of the region. It is woven using primitive techniques. Though softer than the rari it does not compare with the woollen suiting imported from abroad, resulting in a decline in its usage.

Palm-leaf engraving and etching of Raghurajpur, Odisha, is an age-old hereditary craft that is practised by the chitrakar artist families. Stories from the great epics are etched on the taad or palm leaf. Raghurajpur, located close to the Jagannath temple in Puri is home to artists, painters, sculptors, wood-carvers, and toy-makers. It is believed that this craft originated during the building of the temple and continues even today.

Palm leaf work is practiced widely across several regions in Haryana. Products such as shallow circular tray called chakore, narrow necked basket with lid called sundhada, bread basket with lid called baiya, cylindrical basket with lid called koop, basket called khara, hand fan called bijna, mat and carry bags. Tools such as needle called gandoi is required in the crafting process.

A large range of products are made out of the different parts and varieties of the palm tree. Palmyra fibers and leaves are braided in various patterns to make baskets. Mats and baskets are also woven from the stem of the date palm. While crafted all over Kerala the well known areas include Anavoor, Manvil, Neyyatinkara, Nedumangad, Perumkadavila, Parassala and SreeKariyam in Thiruvananthapuram district. The tender palm leaves are separated from the strips and joined together by winding a running strip over them. This is then folded like a ribbon and fastened by a thin strip of leaf to connect the layers at intervals, thus yielding a uniform and rhythmic pattern with natural colours and a fine texture. The baskets are traditionally constructed with vertical and diagonal plaiting or through coiling, made with a square base and a circular rim. Often they are made of two layers - the inner, woven with a coarse, natural colored ola while the outer, which is woven with colorful finer strips. The mature leaf is used to make crude baskets of little structural strength, used for packaging fish, fruit and vegetables. Naar, inner section, of the leaf stem, on the other hand, is used to make storage and shopping baskets. Although extremely strong, these baskets have little market appeal due to their mottled coloring; consequently, the naar is now dyed to give it a bright and lacquer-like appearance Other products made include suitcases, patta / cup made by folding a section of the ola, leaf that is used to drink padneer, the fresh juice of the palmyra fruit, boxes, bags, baskets, screens, chiks, mats, glass holders, and vases. Basket-making is practiced by the women, sieves and winnows, hand fans and square mats, boxes of all varieties and baskets in a variety of colors; dehusking trays palm leaf garlands, etc Palm-leaf and -stem weaving is a thriving craft in southern Kerala also. Previously only mats for local consumption were being woven; nowadays bags, hats, and suitcases are made both for the Indian and foreign markets. The tools used are basic and include splicing machines , scissors, needles, nail frames

Several products are made out of the different parts of the palm tree. Palmyra fibres and leaves are braided in various patterns to make baskets. Mats and baskets are also woven from the stem of the date palm. he tender palm leaves are separated from the strips and joined together by winding a running strip over them. This is then folded like a ribbon and fastened by a thin strip of leaf to connect the layers at intervals, thus yielding a uniform and rhythmic pattern with soft colours and a fine texture. The products made include suitcases, boxes, bags, baskets, screens, chiks, mats, glass holders, and vases.

Several products are made out of the different parts of the palm tree. Palmyra fibres and leaves are braided in various patterns to make baskets. Mats and baskets are also woven from the stem of the date palm. he tender palm leaves are separated from the strips and joined together by winding a running strip over them. This is then folded like a ribbon and fastened by a thin strip of leaf to connect the layers at intervals, thus yielding a uniform and rhythmic pattern with soft colours and a fine texture. The products made include suitcases, boxes, bags, baskets, screens, chiks, mats, glass holders, and vases.

Several products are made out of the different parts of the palm tree. Palmyra fibres and leaves are braided in various patterns to make baskets. Mats and baskets are also woven from the stem of the date palm. These mats are of the coarse variety with counts ranging from 16 to 26 and are made in the districts of North and South Arcot, Salem, Thiruchirapalli, and Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu. Manapad, a sandy village in Tirunelveli district is famous for its palm-leaf products. Here the tender palm leaves are separated from the strips and joined together by winding a running strip over them. This is then folded like a ribbon and fastened by a thin strip of leaf to connect the layers at intervals, thus yielding a uniform and rhythmic pattern with soft colours and a fine texture. The products made include suitcases, boxes, bags, baskets, screens, chiks, mats, glass holders, and vases. Basket-making is practised by the women of the area. Chittarkottai in Ramanathapuram district specialises in hats and bags; here a leaf strip is used to fasten the erks as the erks are thought to make the article more durable. Ramanathapuram is also known for its beautiful sieves and winnows, while Daripatnam specialises in hand fans and square mats. Rameshwaram is known for its square boxes --- decorative, with raised patterns, and commonly used as trinket boxes. In the Ramanathapuram district, a community of women weave baskets in a variety of colours with abstract animals, birds, and geometric designs displayed on them. A colourfully dyed palm-leaf moram or dehusking tray is made at Tirunelveli. The palm-leaf baskets of Chettinad are famous for the square effect of their weave. Betel nut cases are made of a mixture of palm leaf and metal. The articles from palm leaf made at Nagore include bags, dinner cases, and ornamental folding fans. Here the tender palm leaves have their ribs removed and are then dried in the sun. The upper end is smoothly rounded off and the lower end has a flat edge. A 10 inch fan has 56 blades and an 8 inch fan has 37 blades. The blades are uniformly cut with an iron die. The handles are purple and made by splicing bamboo it into narrow strips. The blades are tied together by copper wire through holes on them and sewn together to spread out as a fan. The sewing has to be done in such a way so that the stitching is not visible. Floral motifs are painted on the blades, thus giving the fan an attractive appearance. Palm-leaf and -stem weaving is a thriving craft in southern Kerala also. Previously only mats for local consumption were being woven; nowadays bags, hats, and suitcases are made both for the Indian and foreign markets.

Several products are made out of the different parts of the palm tree. Palmyra fibres and leaves are braided in various patterns to make baskets. Mats and baskets are also woven from the stem of the date palm. he tender palm leaves are separated from the strips and joined together by winding a running strip over them. This is then folded like a ribbon and fastened by a thin strip of leaf to connect the layers at intervals, thus yielding a uniform and rhythmic pattern with soft colours and a fine texture. The products made include suitcases, boxes, bags, baskets, screens, chiks, mats, glass holders, and vases.