Tablet weaving - the ancient method of weaving ornamental belts and apron bands - is assumed to have come to Nepal from Tibet. It is practised only in some northern areas and in Kathmandu, where a large number of Tibetan refugees have settled. Here tablet weaving has become more tourist-oriented: rather than adorning a traditional dress or apron a tablet-woven band might appear around a tourist's neck as a camera strap or as a tie-belt around jeans.

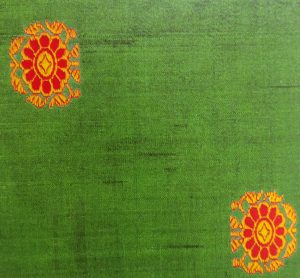

Tanchoi saris are worn as a traditional attire by Gujarati women. Believed to originate from China, this art was first introduced in India at Surat, Gujarat. The art is named after the three brothers who brought this art to India. The art then traveled to Banaras from where the experimentation of Tanchoi with satin weave and zari began. The new versions of Tanchoi gained popularity in Banaras and also in Gujarat and in worn by people across India. The Tanchoi weave is famous for the intricate and small weaving patterns over the fabric. Motifs include- birds and peacocks, flowers, etc. They often have spots all over the surface and are woven in the dual colour strap. The background fabric has a satin appearance giving it a unique effect. Some extra threads are added to give the saris an appearance of being embroidered. [gallery ids="176489,176490,176491,176492"]

Tangail saris made in the Burdhwan cluster of West Bengal originated in Tangail region of Bangladesh. During the partition, many weavers migrated from Tangail to Burdhwan and continued their craft. Initially, silk weft were used with the combination of cotton warps. Gradually, cotton became more popularised and was used in both warp and weft. Cotton yarns of 80s and 100s count are generally used with higher reed count. Tussar silk yarn, mercerized cotton yarn and dyed twisted cotton yarn are used in borders of the saree for extra warp. The body of the saree has repeated extra weft motifs and the pallu and border is sometimes weaved with zari and silver thread to give a subtle lustre. Both the body of the saree and pallu is weaved using jacquard loom. These sarees are also known as begum bahaar. These days, stoles, scarves, home furnishing materials are also created with this weaving.

A unique weaving technique known only to the Dangasia community, Tangaliya is identified by the tiny dots of extra weft that are twisted to give the effect of bead embroidery. The fabric, woven on a pit loom, is usually narrow in width and 20 feet long. It is then cut into half and the two sections are stitched together. The intricate method of twisting the extra weft while the weaving is going on creates beautiful linear patterns and forms.

Sitarmaker Street in Miraj is a living example of a wonder called Tanpura. A dried pumpkin, a stick with some strings attached is all needed to bring music to life in this small town of Maharashtra. The pumpkins are specially brought from Pandharpur and only those varieties are used which are inedible. The pumpkins are also used a floats while crossing river. The wood that is used should also be chosen with utmost care. The shape, thickness and seasoning all need to account for while making a good tanpura. Ustad Abdul Karim Khan saheb, the founder of Kirana gharana of Khayal finds close association with discovery of Tanpura. Abdul Karim Khan has a special association with the place. As much as Miraj is associated with the tanpura, it is also associated with Ustad. It was after listening to his record, playing in a shop, that Bhimsen Joshi decided at the age of 11 to run away from home to learn music. Music can become as obsessive as that. The town comes to life each year during the three-day music festival coinciding with the Urs of Hazrat Pir Khwaja Shamana Mirasaheb, a great sufi saint of the Chishti tradition. It was a tradition started by Ustad Abdul Karim, his descendants along with the instruments makers continue this tradition in his honour. Khan sahebs contribution in bringing Tanpura into popular music culture cannot be missed. Kirana Gharana's mainstay was in subtle nuances of tones which is brought into focus by the Tanpura itself. He would himself sit the makers to get the right tonal quality and resonance needed for his music.

The art of inlaying brass and copper wires in wood is called Tarkashi. Traditional craft articles such as khadaun (wooden slippers), book holders and screens are crafted by the artisans. Additionally contemporary items such as bottle racks, trolleys, and television cabinets as well as coasters are created. The tools used for the crafting process are cheni, pulki, tahaki, Chaurasi- types of chisel, punches, wooden mallets and hammer. The metal wire inlay work known as tarkashi was originally from Mainpuri in Uttar Pradesh. Here brass wire was used as an inlay on wood. It was predominantly used for khadaous (wooden sandals), a necessity for every household since leather was considered unclean. The tarkashi craft of Uttar Pradesh is known today for its fine inlay work with brass wire, brass strips, and motifs on dark sheesham with fine dots and designs with lines. This technique is being used extensively for furniture and boxes, particularly in Pilkhuwa.

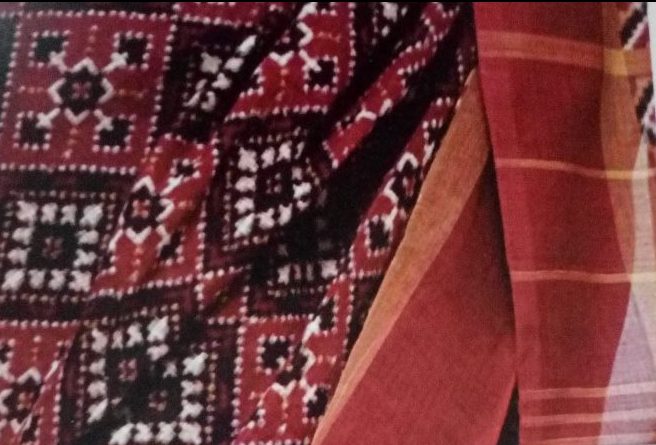

Tawlhlohpuan is an important Puan shawl in the textile heritage of Mizoram. Its distinct name means “to stand firm or not to move backward”. Named after a courageous Mizo soldier it symbolizes bravery and glory. Customarily the Tawlhlohpuan is draped like a warrior wears it. Its weaving is more time consuming and complex as compared to other puans. For the ground fabric the undyed cotton yarn is used for the warp and the indigo dyed black cotton is used as weft. The weft faced plain weave helps construct patterns over the solid black or blue base warp layer. The colors are chosen in sync with the background and foreground of the shawl, to ensure a visual and textural harmony. Combination of red with white and shades of blue with black are most commonly used for dyeing the Tawlhlohpuan. This long process enables the weaver to showcase their skill and effort.

The dance of kathakali has the most outstanding head-gears known as kiritams. These are designed as per the qualities of the dancers: pacha (green) is benevolent and noble; kathi (knife) symbolises evil and demon-like characters. Each of the head-gears have two types of coronets, of two superimposed domes ending in a bud-shaped finial, a large circular disc behind it, and a halo between the coronet and the disc. It is carved out of wood and from the hollow bottom up to the top of the first dome, every row is decorated with closely knit silver beads on a red scarlet base and beetles' wings set vertically in parallel rows. Glass pieces fixed on aluminium foils, large glass flower petals, and small silver beads are in the centre. Ornamental silver fringes are above the peacock shape made of green glass pieces, between the top of the second dome and the finial. The top of the dome has concentric circles with the rows of decoration repeated. The disc is like a perfect piece of jewellery, is picturesque on both sides, and has a circular row of vines of golden stems and leaves, green buds, grapes with peacock feather stems, and a golden circle of foils converging on a round piece of glass in the centre.The appearance of the convex shaped rising circle of vines is like a fully blossomed flower. The players who come in the next category have beards of three colours: red, white, and black. Red bearded characters are vicious and vile, white bearded characters are strong, gentle, devoted, and loyal (like Hanuman), and black bearded characters are the destroyers (like Kali), and include hunters and the like. The characters with the red and black beards have large head-gears with decorations more or less similar to the previous headgear. There are some differences: the edge of the disc is decorated with woollen tufts, their colour is same as that of the beard, the base of the peacock stem is rolled into oval shaped flowers, and in place of the vines, grapes are fixed on the disc. Hanuman's head-gear is like a Chinese hat with two domes, ending in a bud-like finial, adorned with tassels. The rest of the frame is in cane and the outer surface is covered by white flannel while the bottom with is covered in scarlet and has four lines of silver ornamental fringes suspended in concentric circles and a silver crescent. Long artificial locks also float down. The head-gear of sages or rishis consist of two domes, the lower being larger. The usual adornments are there along with twisted coils and, in addition, there is a rudrakshamala (rosary of several faceted seeds) encircling the dome. The hunter's head-gear resembles an expanding lotus, the cane frame rising from the bottom, covering almost half the height. This is covered with a dark cloth which is decorated with silver petals resembling the screw-pine blossoms. Krishna has a special head-gear of a conical hemispherical dome with a woollen garland of different colours encircling its tip. Over this are fixed the eyes of peacock feathers to create the form of an expanding lotus. There is has a margin of oval shaped flowers formed by peacock feathers. An oval piece of blue or black ornamented cloth hangs behind the coronet and forms a beautiful cover.

In Andhra Pradesh, ikats and brocaded silks are woven under the supervision of master weavers in their homes. The richer the silks woven the better the wages; the weaver who makes plain silks does not earn much. Tie-and-dye weaving is concentrated in Pochampalli in Nalgonda district and Chirala in Guntur district. The craft involves a delicate and elaborate process in which the warp and the weft are tied and dyed according to a predetermined design. Both cotton and silk are used. A special item called telia rumal (literally 'oily handkerchief') is made at Pochampalli; the yarn is dipped into an oily solution before weaving. The patola or ikat saris of Pochampalli have a large variety of geometrical designs; the patterns are more pronounced at Chirala. A great variety of cotton lungis or cotton sarongs (draped around the waist ) for men are also woven in Andhra Pradesh, often with some ikat designs in the body or on the border. The exquisite saris and telia rumals of Pochampalli and the Asia rumals of Chirala were exported from India even in ancient times. Now the market for them has increased to a great extent and the craft flourishes to this day in these centres.

Shifting political dominance and boundaries within the South East Asian region have left multi-cultural imprints in a number of fields, including art and architecture. This immense diversity of art and architectural forms, corresponding to different periods of Lao history, and its influence can be seen, even today in the graceful Khmer temple complexes, elegant Buddhist wats (temples), heritage sites, colonial architecture and stilted rural dwellings. Buddhist religious structure such as pagodas, wats, stupas dot the landscape. Their interiors are painted or carved with Buddha images and other religious symbols. The principal construction material for these structures, until about the 19th century, was wood. This made them vulnerable to both to the ravages of war, fire and the tropical climate. Many palaces and temples have been partially or wholly destroyed and the original construction lost. In some cases, much of it has been rebuilt, using modern techniques and materials rather than old traditional methods and styles. However, from the earliest Hindu temples and shrines to the later magnificent Buddhist structures, temple architecture had a singular purpose - to teach, enlighten and inspire worshippers.

|

|

|

|

Vadaserry, a tiny village on the outskirts of Nagercoil, is dedicated to crafting temple jewellery. There are 58 units, with 224 traditional artisans, engaged in the manufacture of temple jewellery. The tradition goes back to at least as early as 14th Century AD. There is need to give a fillip to the traditional art which is a traditional profession for this group of craftsmen which is in danger of languishing. Even though a Geographical Indication tag had been given to this Kanyakumari temple jewellery craft. These traditional jewels are made of silver and 24 ct gold leaves (thin gold foil). The fabrication of the jewels is made of silver linings .The top visible layer has natural un-cut stones, while gold leaf is used to form the lining for the stones. This ensures that the jewels retain their sheen for years. The designs are based on traditional South Indian temple jewellery, which have adorned the deities in the temples. This traditional jewellery was also used by royalty, like the Rajas of Chettinad and Ramnad. This continues to be part of the jewellery used for classical dances like Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi. The traditional temple jewellery is made only in Vadasery.

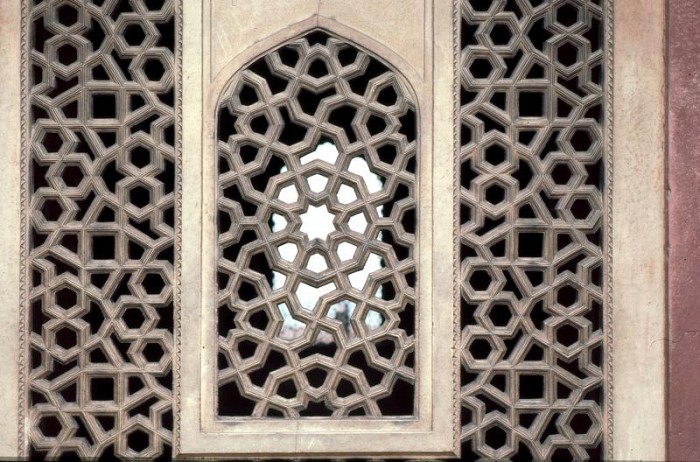

The Sompuras is one of the communities of stone temple carvers and monument builders. Employed in temple building across India the craft is considered a holy duty. The masons and stone carvers specialize in creating idols, motifs for religious structures. Religious structures are built regionally to show the use of local style Gujarat craftsperson are proficient in intricate stone carving such as the Jaali (fretwork). Other architectural fixtures and structural elements are Jhurukha, stone brackets and stone screens. Sculpted images and motifs are made from a variety of stones, especially marble. Iconography and aesthetic beauty of the temples also executed with the marble and stone which demonstrate the craftspersons skill and respect for the material of the craft. The ornaments that the idol is decorated with are often made from silver metallic sheets or agate stone which is also native to Gujarat. [gallery ids="176573,176574,176575,176576,176577,176578"]

The main centres for this craft are Mohali, Ropar, Ludhiana and Hoshiarpur. The products made include matkas, flower pots, diyas, miniature temple structures, and toys, adorned with colours, paints, gutas, mirrors and other forms of ornamentation. The designs are both traditional and contemporary. Ceramics are also made by the use of modern furnaces at the same centres. The main centre for ceramics is Mohali near Chandigarh.

As Chandigarh is a relatively new city devoid of a tradition of crafts, most of the craftsperson’s are from the urban community. Thus one can largely find studio potters and stained glass artisans, who are combining the traditional techniques with the contemporary or the East with the West to create pieces of art and utilitarian objects.

Terracotta and Clay work or Mitti da Kaam can be said to be one of the oldest and the most widespread handicrafts. Remains of the same have been found at the sites of the earliest civilisations. As a matter of fact archaeological digs in the Chandigarh area have yielded ancient Indus Valley Civilisation (c. 2500- 1700 BCE) artefacts, predominantly pottery.

For this craft the raw material is ordinary clay, derived from the local mud hills or the pahad. The clay is prepared and then wedged to remove impurities and air bubbles. It is then shaped either by hand, wheel or moulded into the desired shape. Then as per requirements, products are dried, fired and glazed. The clay or terracotta products are graded according to their colour, strength and water absorption capacity.

Urban kumhars can be found in colonies within the city, while communities of traditional kumhars can be found in villages around the city, for instance in Kishangarh, Saketri, Hallo Majra and Dadu Majra.

In terracotta jewellery, the raw material used is a fairly coarse, porous type of lean clay. This clay is usually sourced from the tank beds and is then dried in the sun, after which it is powdered and put in a tub containing water. This is stirred well and filtered through a sieve. This sieved clay is collected and allowed to settle. After a few days the excess water is decanted and the clay, in a slurry form, is dried in trays. The clay is made into coils or thin slabs and cut into the required sizes and shapes on the river bank before it is ready for marketing.