Tortoise Shell Craft of Andhra Pradesh,

Vishakapatnam in Andhra Pradesh is the main centre for the crafting of tortoise shell, in combination with bone, into trinket boxes. The shell surface of the box is covered with intricate patterns of bone fretwork so that through this perforated lacy surface the orange glow of the shell can be seen. The designs used include fine geometrical patterns, epic figures, and animals fringed by floral patterns. Horns, bone and tortoise shells are also combined to make products at Vishakapatnam and Secunderabad. Bone is also combined with sandalwood, ebony, and tortoise shells to create intricate patterns of fretwork that are mounted or inlaid. The best known products are ornate octagonal jewel boxes with the bone net cover.

Vishakapatnam in Andhra Pradesh is the main centre for the crafting of tortoise shell, in combination with bone, into trinket boxes. The shell surface of the box is covered with intricate patterns of bone fretwork so that through this perforated lacy surface the orange glow of the shell can be seen. The designs used include fine geometrical patterns, epic figures, and animals fringed by floral patterns. Horns, bone and tortoise shells are also combined to make products at Vishakapatnam and Secunderabad. Bone is also combined with sandalwood, ebony, and tortoise shells to create intricate patterns of fretwork that are mounted or inlaid. The best known products are ornate octagonal jewel boxes with the bone net cover.

Tortoise Shell Craft of Goa,

Tortoise shells are crafted in combination with bone, into trinket boxes. The shell surface of the box is covered with intricate patterns of bone fretwork so that through this perforated lacy surface the orange glow of the shell can be seen. The designs used include fine geometric patterns, figures, and floral patterns.

Tortoise shells are crafted in combination with bone, into trinket boxes. The shell surface of the box is covered with intricate patterns of bone fretwork so that through this perforated lacy surface the orange glow of the shell can be seen. The designs used include fine geometric patterns, figures, and floral patterns.

Tortoise Shell Craft of Pondicherry,

Vishakapatnam in Andhra Pradesh is the main centre for the crafting of tortoise shell, in combination with bone, into trinket boxes. The shell surface of the box is covered with intricate patterns of bone fretwork so that through this perforated lacy surface the orange glow of the shell can be seen. The designs used include fine geometrical patterns, epic figures, and animals fringed by floral patterns. Horns, bone and tortoise shells are also combined to make products at Vishakapatnam and Secunderabad. Bone is also combined with sandalwood, ebony, and tortoise shells to create intricate patterns of fretwork that are mounted or inlaid. The best known products are ornate octagonal jewel boxes with the bone net cover.

Vishakapatnam in Andhra Pradesh is the main centre for the crafting of tortoise shell, in combination with bone, into trinket boxes. The shell surface of the box is covered with intricate patterns of bone fretwork so that through this perforated lacy surface the orange glow of the shell can be seen. The designs used include fine geometrical patterns, epic figures, and animals fringed by floral patterns. Horns, bone and tortoise shells are also combined to make products at Vishakapatnam and Secunderabad. Bone is also combined with sandalwood, ebony, and tortoise shells to create intricate patterns of fretwork that are mounted or inlaid. The best known products are ornate octagonal jewel boxes with the bone net cover.

Toys of Karnataka,

Intricate and mind-boggling puzzles, scaled down copies of cycles, rickshaws, and motorcycles, decorative items, and several other products are made with wire. Wire work is a hereditary craft which uses simple tools to create wire toys and puzzles that are sold in local fairs. Wire craftspersons can be found in many parts of India. The toys and puzzles made by them fascinate children and adults alike. The puzzles are normally made with a single wire that is looped and twisted in a complex manner to make a puzzle that is difficult to solve.

Intricate and mind-boggling puzzles, scaled down copies of cycles, rickshaws, and motorcycles, decorative items, and several other products are made with wire. Wire work is a hereditary craft which uses simple tools to create wire toys and puzzles that are sold in local fairs. Wire craftspersons can be found in many parts of India. The toys and puzzles made by them fascinate children and adults alike. The puzzles are normally made with a single wire that is looped and twisted in a complex manner to make a puzzle that is difficult to solve.

Toys of Tamil Nadu,

Toy-making is a widely practised craft and different materials are used in their production. Shell toys, are cheap and easy to make, consist of large individual shells or small ones stuck together to form an animal or a person. A popular variety of homemade toys is made of leaves, fruit skin like pomegranate skin and twigs. Some toys are made of paper, twigs and wire, crafted only at festival-times. Vahanas or vehicles made of wood on wheels are usually pull-along toys for the child. Madurai specialises in metal-creations mainly brass insects which are remarkably life-like because of careful attention to detail. In areas around Kumbakonam, toys are also made of pith, which is the hard core of a water reed found in the tanks, swamps and lakes. The ivory-coloured reed is soft, smooth, extremely pliable and is fashioned into playthings. In Mannapadu toy animals are made out of palm leaves, which are dipped into colour and interwoven into creative forms. Toys made of wood are lathe-turned and lacquered, especially cooking vessels and walkers known as kadasal. These are brightly coloured, inexpensive and very popular. Carved wooden toys like dolls and elephants which exhibit the range of skills of the artisans are also made.

Toy-making is a widely practised craft and different materials are used in their production. Shell toys, are cheap and easy to make, consist of large individual shells or small ones stuck together to form an animal or a person. A popular variety of homemade toys is made of leaves, fruit skin like pomegranate skin and twigs. Some toys are made of paper, twigs and wire, crafted only at festival-times. Vahanas or vehicles made of wood on wheels are usually pull-along toys for the child. Madurai specialises in metal-creations mainly brass insects which are remarkably life-like because of careful attention to detail. In areas around Kumbakonam, toys are also made of pith, which is the hard core of a water reed found in the tanks, swamps and lakes. The ivory-coloured reed is soft, smooth, extremely pliable and is fashioned into playthings. In Mannapadu toy animals are made out of palm leaves, which are dipped into colour and interwoven into creative forms. Toys made of wood are lathe-turned and lacquered, especially cooking vessels and walkers known as kadasal. These are brightly coloured, inexpensive and very popular. Carved wooden toys like dolls and elephants which exhibit the range of skills of the artisans are also made.

Traditional Board Games of Karnataka,

Annual summer vacations in my grandparents’ home, in Gobichettipalayam, a small town in Tamil Nadu, to which my paternal kannadiga ancestors had migrated was a world, completely apart, from our normal convent-school-centered childhood. Walking barefoot in the theruvus, streets, swimming in the vaykal, canal, making cow-dung cakes and playing traditional games, were new experiences. In contrast to hockey, basketball and seven tiles, the games we were accustomed to, we learnt the nuances of eidu kallinnna atta (five stones) kunte bille ( hopscotch) and board games like alugulimanne (also known as pallanguli in Tamil). My sister and I counted tamarind seeds in the seven pits of a double rowed, beautifully carved, folding wooden board. Substituting for the seeds, were sometimes, cowrie shells or orange colored annatto seeds. Visits to relatives in Nanjangud and Bangalore introduced us to other traditional board games, like huli kuriatta (tigers and goats) and chowkabara, a race game. These were and are, in the predominantly agrarian societies of India, leisure pastimes, played by young and old. World over, board games were as significant as trade and religion, for transmitting cultural forms and ideas. As objects of art, they were treasured possessions and status symbols, often finely crafted and elaborately decorated to reflect the aspirations of their owners.

Annual summer vacations in my grandparents’ home, in Gobichettipalayam, a small town in Tamil Nadu, to which my paternal kannadiga ancestors had migrated was a world, completely apart, from our normal convent-school-centered childhood. Walking barefoot in the theruvus, streets, swimming in the vaykal, canal, making cow-dung cakes and playing traditional games, were new experiences. In contrast to hockey, basketball and seven tiles, the games we were accustomed to, we learnt the nuances of eidu kallinnna atta (five stones) kunte bille ( hopscotch) and board games like alugulimanne (also known as pallanguli in Tamil). My sister and I counted tamarind seeds in the seven pits of a double rowed, beautifully carved, folding wooden board. Substituting for the seeds, were sometimes, cowrie shells or orange colored annatto seeds. Visits to relatives in Nanjangud and Bangalore introduced us to other traditional board games, like huli kuriatta (tigers and goats) and chowkabara, a race game. These were and are, in the predominantly agrarian societies of India, leisure pastimes, played by young and old. World over, board games were as significant as trade and religion, for transmitting cultural forms and ideas. As objects of art, they were treasured possessions and status symbols, often finely crafted and elaborately decorated to reflect the aspirations of their owners.

Mysore, under Mummadi Krishnaraj Wodeyar 111(1794-1868) was a hub, for creative expressions of arts and crafts and a centre for producing games, pawns and dice. Kautuka Nidhi, one of the nine chapters on “ Sports and Pastimes”, part of the encyclopedic work Sritatwanidhi ("Noble Treasury of Philosophy" ) compiled under the patronage of Mummadi, describes the various board and card games of the era. Krishnaraja was a man given to religious and astrological speculation and the walls of the Jaganmohan Palace of Mysore, are covered with paintings of astrological charts and tables and an endless series of board, dice and card games.

Kreeda Kaushalya is a laudable initiative by Mysuru based crafts foundation Ramsons Kala Pratishthana, to research and revive the traditional board games of Karnataka, using the living, crafts traditions of the State.

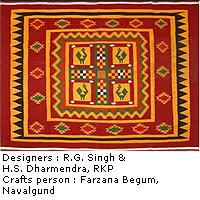

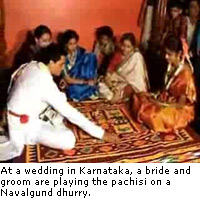

Navalgund Game Board Dhurry

Navalgund is a small town 40 kms from Hubballi (Hubli) in Dharwad district of Karnataka, once known for its navilu-gundas, or ‘peacock groves’. The exotic peacock is the inspiration for the design of the vibrant Navalgund cotton dhurry or ‘ jamakhana” woven in this town, in pit looms, traditionally by women weavers from the Muslim community.The designs are geometrical, embellished with floral and bird motifs. Till not very long ago a ‘char-mor’ jamakhana, with saada phool, geometrical floral forms and four stylized peacocks, with the pachisi or, pagade atta, woven in the centre, was part of the bridal trousseau and also pledged to secure loans.

The team of designers from Ramsons have revived this unique floor covering cum board game.

|

|

Algulimanne

This is a brass alguli manne or mancala board crafted using the 'cire purdue' or lost wax process. Along with regular double rows of seven pits, the board has two larger storage pits, bordered by a prabhavali, arch, topped by a keerthimukha, lion face. The two sides have been intricately crafted with the motif of the mythical double headed eagle, gandaberunda in the centre. The board stands on four legs moulded into lion motifs.

|

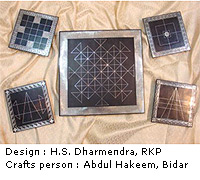

Game Boards in Bidri Craft

Bidricraft, originated in Bidar in Northern Karnataka is a craft of damascening or inlaying silver onto a dark metal plate made from an alloy of zinc, copper, tin and lead. Tarkashi is the art of inlaying silver wire whereas Tainishan is the craft of – inlaying silver sheets. The game board in the centre is the game ‘'Elephants and Men' ,with the border beautifully inlaid in the famous 'phuljari' design.

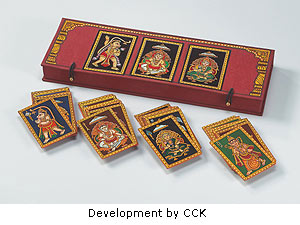

Several organisations like and The Crafts Council of Karnataka has also been independently working on traditional board games of Karnataka. CCK has replicated for the first time one of the 13 Mysore Chada or card games – the Navin Rama Chada with 36 cards.

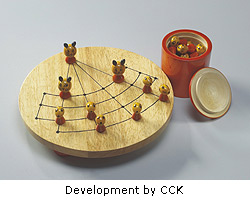

Ansuya Pavanje, Founder Secretary of CCK had a sample of a beautiful round shaped version of huli kuri atta, with pawns of tigers and sheep made in natural dyed, lacquered hale wood, made by her father, the eminent Karnataka artist Pavanje. This has been revived by CCK and beautifully executed by craftsperson

Kauser of Channapatna

Chauka Bara is a 'Race Game' where in two to four players race their respective coins on a board of 5x5 squares to reach the inner most square. The movement of coins is controlled by throw of four cowrie shells, hence it is a game of chance. Since each player has four coins, he can decide which coin to move, hence it also a game of strategy race game. CCk has developed a chaukabara board game in the craft of Chittara, the mural tradition of the Shivamogga region of Karnataka, executed by state award winner Radha Sullur.

There are several benefits of playing board games. Board games are played to improve memory, counting skills and honing strategy. For children weak in mathematics and lacking concentration, Aliguli Mane (Mancala) is a traditional antidote. Alignment games like Nava Kankari will help unclutter the mind. Hunt games like Adu Huli and Aney Kattu enable kids to develop a killer instinct to succeed. Race games like Pagade, Chauka Bara and >Panchi, improve the competitive spirit.

|

|

|

|

Traditional Dhaka-Cloth Weaving,

Dhaka cloth, beautifully patterned and coloured, is woven on a small loom that has a width smaller than those used for other woven textiles. Dhaka cloth - both the traditional black, white, red and orange and the new modern Dhaka textiles which use a wide range of colours and yarns - has become the best known of Nepalese textiles. Each of these pieces of weaving is a creation integrating new ideas with the old.

Dhaka cloth, beautifully patterned and coloured, is woven on a small loom that has a width smaller than those used for other woven textiles. Dhaka cloth - both the traditional black, white, red and orange and the new modern Dhaka textiles which use a wide range of colours and yarns - has become the best known of Nepalese textiles. Each of these pieces of weaving is a creation integrating new ideas with the old.

TRADITIONS

The cloth is mainly used in making men's caps (topi), the traditional blouse worn by women (chaubandi cholo) and shawls (labeda sulwal). The traditional colours of Dhaka cloth are black, white, red and orange, but no two topis or shawls are identical: each has its own individual pattern, reflecting the creativity and skill of the weaver. The Nepali cap is lightly worn and brim-less, with a top creased corner resembling a peak, it is one of the symbols of Nepal and all officials wear it in government offices. While the formal cap is black, the daka topi is in many colours and elaborate designs.

Although throughout Nepal factory-made cloth has replaced much of the traditional hand-woven material for clothing, the demand for the individually made Dhaka cloth has continued. Most men invest in a new topi for special occasions such as harvest festival or the new year (dasain). Often something unusual is sought, for example, a commission to design a topi (strips of 18 cm X 70 cm) with a new pattern to be worn at a wedding. Sometimes a bridegroom will wear full national dress made from Dhaka cloth.

The Dhaka shawl (90-100 X 200 cm) is usually worn round the shoulders with the ends crossed over one shoulder so that the whole upper part of the body is enveloped; sometimes it is draped over the head. Since the early 1980s an amazing upsurge of Dhaka-cloth production has taken place since a wide range of yarns and colours became available to the weavers.

Most weaving takes place during the dry session, October to March, when little fieldwork is possible. Weaving forms part of the domestic scene and many girls know how to weave by the time they are ten years old. Often friends and relations work in groups, for companionship and mutual encouragement, and sometimes sharing some of the supporting posts for the loom.

NOMENCLATURE & HISTORY

One story holds that the colourful topi, which has largely replaced the plain, often black, topi, was introduced by a minister who returned with the idea from Dhaka (Bangladesh); others believe that the name was given to the cloth simply because many items, such as cloth and thread, came to Nepal from or through Dhaka in Bangladesh or because Dhaka muslin resembled the fine Nepalese weaving. However, the method of pattern weaving practised around Dhaka, called Jamdani, differs considerably from that practised by Nepalese weavers. It is also possible that Hindu weavers, fleeing from Dhaka at the time of the Muslim invasions, settled in or near Nepal and influenced Nepalese weavers. It is curious, though, that the main centre of Dhaka weaving, Terhathum, is in an area in the mountains that was difficult to reach until quite recently; it is also not in a border area. Nevertheless, according to the elders of a Terhathum weaver, this type of weaving has been known for generations, although formerly the patterns were applied mainly to the ends of sashes and waistbands rather than topis.

PRACTITIONERS & LOCATION

The main centre of Dhaka weaving, Terhathum, is in an area of the middle mountains some eight hours, walk from a road-head that was difficult to reach until quite recently. Nevertheless, according to the elders of a Terhathum weaver, this type of weaving has been known for generations, although formerly the patterns were applied mainly to the ends of sashes and waistbands rather than topis. Today some of the finest Dhaka cloth is woven by Limbu women from eastern Nepal, though some Rai women are also involved. The majority of weavers are women: very few men weave Dhaka cloth. In Kathmandu, Dhaka weaving is generally done in some factory units, whereas, in the hilly areas of country like Palpa, Dhankuta, Tehrathum etc., this type of weaving is all home-based.

Dhaka cloth is made by the individual weaver in her own home at such times as she chooses or when her daily and seasonal tasks in the home and on the farm allow. Further the women weaver can decide part of her own economic destiny which should be a factor of importance in rural development.

TECHNIQUE & PROCESS

Dhaka-cloth looms are of no standard size. There are regional variations of warping and weaving methods, but the basic principle is the same. The bamboo and woodwork are usually prepared by men who are members of the weaver's family or friends. Among the permanent features is the upright bamboo post that support the loom.

Some weavers use just one post to support the warp, around which the length of the warp with the tension cord is folded. The weaver sits in front of the cloth beam to which one end of the warp is attached. As the cloth is woven and wound on to the cloth beam, the weaver loosens the tension cord and allows as much of the warp to move towards him/her as he/she requires before transfering to the heddles, so there is hardly any wastage.

There are various ways of preparing the yarn for warping: the hand-spun cotton yarn, which is the one traditionally used, is wound from the spindle on to a split bamboo cage spool to form a skein. Mercerised sewing cotton thread, manufactured in southern Nepal, is now used by many Dhaka weavers. As this is sold in rolls on cardboard cylinders, similar to bobbins, weavers can use them as they are, employing an even number at any given time in order to speed up the warping process.

SUPPLEMENTARY-WEFT INLAY (BROCADE)

The best-known method of Dhaka-cloth weaving is a plain ground weave with a supplementary weft of a different colour laid alongside the ground weft in the regular sheds in selected areas to create a pattern. For the white ground weft, weavers use one or more strands of single cotton or one strand of two-or-three-ply mercerised sewing cotton. For the supplementary weft they choose either several strands (six) single-cotton or mercerised cotton or two-ply embroidery cotton, two or three strands at a time. The main traditional colour are red, orange and black, with a little green and blue added sometimes. In the 1980s the locally manufactured acrylic yarn became popular: this brightly coloured yarn is preferred by many of the younger generation, especially for stiff taller topis.

TAPESTRY

Although most Dhaka cloth is woven with weft-inlay patterns, there are some weavers who employ various methods of tapestry. The coloured weft threads in this case are not supplementary but are woven back and forth in their own pattern areas to form the actual structure of the textile. The warp is less visible in this type of Dhaka, although not as hidden as in the textile generally referred to as tapestry, which is entirely weft-faced. One method of joining colour areas is that of dovetailing where two wefts go round a common warp end where the colours meet. But weavers also used inter-penetrated dovetailing where the wefts from the adjacent areas alternately pass into the other area the turn on an adjacent warp-end, rather than a common one, thus forming jagged outlines. Other weavers use double-interlocked tapestry methods where the different colour weft areas are joined by interlocking them in each shed: a ridge of interlocking loops will show at the colour joints on the working face - that is, the side facing the weaver - but is smooth on the other side.

Yet another method, where interlocking is combined with inter-penetrating, is used for some intricate topi patterns.

PATTERNS & MOTIFS

Many Nepalese weavers know about 100 basic patterns and invent new ones all the time. From bold geometric shapes to complex floral patterns some basic motifs - like the zig zag pattern - occur in endless varieties. Many patterns on the miniature (leaf 127 of the Nepalese palm manuscript "Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita", dated A.D. 1015) can be rediscovered in contemporary weaving patterns.

The variety of Dhaka patterns is almost infinite - from bold geometric shapes and temple outlines to complex floral patterns. Only some motifs are given specific names, such as the temple (mandir) and elephant trunk (hatti sunr). Others are interpreted by the individual weavers as diamonds, zigzags, butterflies or flowers, or are just referred to as butta. No two topi strips are identical, and within one length of warp the weaver usually changes the pattern every 70 cm (topi length). This not only makes it more interesting for the weaver but also means also that he/she can offer a passing customer or shopkeeper a choice of patterns. She will cut off the sections required, leaving at least 15 cm of woven cloth: this is dampened to ensure a good grip and then rolled around the cloth beam for the weaving to continue. Although some basic shapes are similar, colour and composition are decided upon by the individual weaver without any drawing or plan, thus making each piece of weaving a unique creation.

One of the best-known topi-strip patterns is based on stepped diamond shapes, inta, along the centre. These are framed by broad, stepped lines and half-diamond shapes emerging from the selvage. According to Limbu weavers, this pattern is easy to weave and is often one of the first patterns for a beginner to practise on. An experienced weaver can weave one or two topi lengths per day with this type of pattern. A more complex pattern might take several days. The diamond appears in many other patterns and is arranged in such a variety of sizes, colours and outlines (smooth, jagged, stepped) and either joined up closely or kept separate - so that each woven strip has a different appearance, emphasised by the irregularities which occur in hand-picked patterns. Often patterns or colours are arranged diagonally, allowing the supplementary weft to continue upwards from patterns to pattern.

Diamonds or hexagonal shapes with a variety of centre patterns are woven into all over designs or linked up to form new patterns, often in such a way that the background becomes the dominant pattern. Positive and negative forms are freely interchanged from one weaving to the other. There are many different types of zigzag patterns and an even wider range based on the outline of a Nepalese temple (mandir). Often this is arranged in stripes and alternated with the elephant trunk or hatti sunr pattern, interspersed with cross designs. Another truly Nepalese design is that based on the national flower, Rhododendron arboreum, or lali guras. Flowers have been the inspiration for many weavers and are incorporated in various shapes into a multitude of patterns.

DEVELOPMENTS

In west Nepal, part-mechanisation of Dhaka cloth weaving has demonstrated that there is a market for mass produced inlay Dhaka cloth. However, it is also apparent that there is an expanding market for the inimitable individually woven Dhaka cloth strips from the kosi Hills - this demand is from locals, as well as from tourists and also for overseas markets.

Traditional Swords, Kora and Khukri

The khukri is the national weapon of Nepal. Over the centuries, it has been wielded with great skill and bravery by the Gurkhas. Legend has it that the Gurkha never sheaths his kukhri without first drawing blood with it; and till today most Gurkhas still swear by this custom. Besides the world renowned kukhri, the kora sword is a historic war weapon of the Gurkhas and has been in use for centuries.

The khukri is the national weapon of Nepal. Over the centuries, it has been wielded with great skill and bravery by the Gurkhas. Legend has it that the Gurkha never sheaths his kukhri without first drawing blood with it; and till today most Gurkhas still swear by this custom. Besides the world renowned kukhri, the kora sword is a historic war weapon of the Gurkhas and has been in use for centuries.

KUKHRI

Worn on the waist along with its scabbard the kukhri has a short, heavy, forward-angled blade that widens towards the tip. The length of the blade is approximately 35 cm to 40 cm. Its weight varies along the length, being heavier towards the pointed tip. This feature adds to the effectiveness of the blow. Another feature adding to its lethal effectiveness is a semi-circular nick at the root end of the edge of the kukhri blade that is about 1.5 cm deep and has a sharp projecting tooth at the bottom. The hilt of the kukhri is straight and is normally without a guard. It is made of either metal or horn, though earlier it was often carved out of ivory too. It may be embellished by carved foliate embellishments in deep relief.

The kukhri sheath is often decorated with big chapes and lockets of gold and silver worked in filigree. An interesting feature is that of a smaller sheath that is attached to the back of the main sheath that houses the kukhri knife. This smaller sheath contains two smaller kukhri-shaped implements, a blunt sharpening steel, and a small skinning knife. The embellishment on the weapon or sheath of the sword is of high quality but designed in a manner that it never interferes with its functionality. The high quality of the ornamentation adds to the value of the kukhri.

The kukhri is not only a weapon but is also used as an implement for cutting through thick vegetation and jungles - till today it has retained its functional and utilitarian character.

Visitors to Nepal often take home a kukhri as a traditional memento.

Craft Location: Bhojpur in East Nepal is noted for its traditional iron ore extraction and purification methods and the craftsmen from this district are also famed for their crafting of the Kukhries. The artisans working with iron ore and charcoal forge the metal in their traditional furnaces. These Kukhries are called the Bhojpuri Kukhries and are considered the finest in workmanship and quality and far over shadow the Kukhries made anywhere else in Nepal.

KORA

Besides the world renowned kukhri, the kora sword is a historic war weapon of the Gurkhas and has been in use for centuries. Its blade is longer than that of the kukhri and measures about 60 cm in length. It comprises of a single edged blade that is narrow at the root end and curves sharply forward, widening to between 9 cm to 12 cm near its end. The weight of the sword lies at its broad tip - this adds great force to a blow. At the edge end of the sword is a slight double semi-circle, which greatly increases its ruthless effectiveness.

The hilt of the kora sword is simple and functional. It features a straight grip, with a circular plate of metal below it that serves as a guard. This is supplemented by another plate of the same size positioned above it as a pommel. Above the pommel is a domed cap enclosing the spiked tang.

The sheath of the kora sword is traditionally of two types. The first is a broad sheath into which the tip can be fitted; the second variety of sheath is shaped like the blade which has to be housed from the back of the sheath and then buttoned down.

Like the kukhri, the kora sword is never excessively ornamented - for the artisan its functionality is the predominant aspect. At the most, the kora sword has gilded rims to the guard and pommel plates, and lac-filled lotus symbols on its blade. The aesthetic appeal of the sword lies is in its simplicity and elegance of design.

Tribal Cotton Weaving of Nagaland,

The hill tribes of north-east have been practising weaving since very old times. Loin loom or back strap loom called to be the oldest and simplest device used in the weaving of cloth is the common loom used by the tribes of Nagaland. The loom is adjustable to the body of the weaver and weaving is done without any mechanical adjustments. Weaving is completely monopolised by the women of Nagaland. It is customary and a social obligation for every girl to learn weaving. Each Naga tribe has its own motif and design which forms its distinct identity. The cloth is warp dominant and the two colours specific to the textiles are red and black that emerge in lines on the white background. The loin loom consists of continuous warp stretched between two parallel bamboos with one end held at door or post and the other end converted into a strap held at the weaver's waist. With self sustaining rural economy, and raw material availability in abundance, the handloom industry of Nagaland has become a mainstay for livelihood. Cotton is grown plentifully by some tribes. This cotton is used for self as well sold to the other tribes of Nagaland for spinning and weaving purposes. Nagaland has created an internationally acclaimed space in the filed of indigenous handicrafts. GEOGRAPHY: Nagaland, homeland for Nagas, is bordered by Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur in West, North and South respectively and international boundary of Myanmar (previously Burma) in East. The tribal state of Nagaland comprises of at least sixteen main tribes and many sub-tribes that follow Christianity as the main religion, Hinduism and Islam are amongst the minority religion. All the tribes are different in terms of their costume, traditions and language but the connection is visible through deep rooted common belief. HISTORY: The originally hunter, gatherer clan of Naga's gradually witnessed a change in their society with advent of missionaries and colonial administration. The Naga handicraft industry is the mainstay of rural economy besides agriculture even today. HANDLOOM INDUSTRY: All the Naga tribes are particularly expressive in their indigenous craft with proficiency in basketry and bamboo crafts, wood carving, textile weaving, metal spears, bead, jewellery and pottery. Spinning of cotton, weaving on loin loom are the crafts that women have to be skilled at in every household. Women carry out the entire weaving process. The cotton handloom industry of Nagaland is entirely dependent on old traditional back-strap loom. The Naga women proficiently use the loom to produce woven textiles. The back strap loom or loin loom is supposed to be one of the oldest methods used for weaving cloth. It is the simplest of all looms with no external devices attached. The continuous warp is stretched between the two parallel bamboos, one end tied to the wall or post and the other held by a strap at waist by the weaver. The tension is regulated through the waist. The warp is winded according to the intended design after that weaving is done. The loom is potable and small but requires strenuous work as it has to be rebuilt every time. The warp is created on the warping frame by vertical lease sticks that ensures the correct thread sequence. This frame is transferred to the weaver who creates the shed through bamboo pole, heald stick, lease stick, and wooden rods, each serving different functions. The width of the fabric derived is small and two pieces are joined together to make the complete garment. The motifs are derived from ritual, beliefs and tribal identity. Simple in shapes and designs, each tribe uses different colours and motifs that establish a distinct identity for them. The procurement of raw material is easy as cotton is grown in abundance by some tribes. The craft industry of Nagaland has survived due to sustenance on self grown and well managed raw materials. The land is naturally abundant with resources that Naga's have utilized for their own benefits and developed a niche in handicrafts industry as well.

The hill tribes of north-east have been practising weaving since very old times. Loin loom or back strap loom called to be the oldest and simplest device used in the weaving of cloth is the common loom used by the tribes of Nagaland. The loom is adjustable to the body of the weaver and weaving is done without any mechanical adjustments. Weaving is completely monopolised by the women of Nagaland. It is customary and a social obligation for every girl to learn weaving. Each Naga tribe has its own motif and design which forms its distinct identity. The cloth is warp dominant and the two colours specific to the textiles are red and black that emerge in lines on the white background. The loin loom consists of continuous warp stretched between two parallel bamboos with one end held at door or post and the other end converted into a strap held at the weaver's waist. With self sustaining rural economy, and raw material availability in abundance, the handloom industry of Nagaland has become a mainstay for livelihood. Cotton is grown plentifully by some tribes. This cotton is used for self as well sold to the other tribes of Nagaland for spinning and weaving purposes. Nagaland has created an internationally acclaimed space in the filed of indigenous handicrafts. GEOGRAPHY: Nagaland, homeland for Nagas, is bordered by Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur in West, North and South respectively and international boundary of Myanmar (previously Burma) in East. The tribal state of Nagaland comprises of at least sixteen main tribes and many sub-tribes that follow Christianity as the main religion, Hinduism and Islam are amongst the minority religion. All the tribes are different in terms of their costume, traditions and language but the connection is visible through deep rooted common belief. HISTORY: The originally hunter, gatherer clan of Naga's gradually witnessed a change in their society with advent of missionaries and colonial administration. The Naga handicraft industry is the mainstay of rural economy besides agriculture even today. HANDLOOM INDUSTRY: All the Naga tribes are particularly expressive in their indigenous craft with proficiency in basketry and bamboo crafts, wood carving, textile weaving, metal spears, bead, jewellery and pottery. Spinning of cotton, weaving on loin loom are the crafts that women have to be skilled at in every household. Women carry out the entire weaving process. The cotton handloom industry of Nagaland is entirely dependent on old traditional back-strap loom. The Naga women proficiently use the loom to produce woven textiles. The back strap loom or loin loom is supposed to be one of the oldest methods used for weaving cloth. It is the simplest of all looms with no external devices attached. The continuous warp is stretched between the two parallel bamboos, one end tied to the wall or post and the other held by a strap at waist by the weaver. The tension is regulated through the waist. The warp is winded according to the intended design after that weaving is done. The loom is potable and small but requires strenuous work as it has to be rebuilt every time. The warp is created on the warping frame by vertical lease sticks that ensures the correct thread sequence. This frame is transferred to the weaver who creates the shed through bamboo pole, heald stick, lease stick, and wooden rods, each serving different functions. The width of the fabric derived is small and two pieces are joined together to make the complete garment. The motifs are derived from ritual, beliefs and tribal identity. Simple in shapes and designs, each tribe uses different colours and motifs that establish a distinct identity for them. The procurement of raw material is easy as cotton is grown in abundance by some tribes. The craft industry of Nagaland has survived due to sustenance on self grown and well managed raw materials. The land is naturally abundant with resources that Naga's have utilized for their own benefits and developed a niche in handicrafts industry as well.

Tribal Crafts of Nagaland,

Tribal craft covers diverse areas: ¨ The Nagas decorate even the most deadly weapons of warfare -- their daos and spears are decorated with hair dyed bright red with manjit and blue from indigo. ¨ The jewellery used by Naga women is simple. Necklaces of beads of cornelian, grass, turned wood beads, silver, and cowries are used. The stones and beads are usually imported but the workmanship is entirely local. ¨ Blacksmithy is a relatively new craft which began after the 18th century. Konyaks are experts at this. In the olden days, tradition required a Naga smith to observe food restrictions while at work; this is no applicable. Agricultural implements like the dao, axe, hoe, scraper, and sickle, and weapons like spear heads, butts, arrow heads, and muskets, as well as ornamental spears for dancing, are all crafted locally by the Konyaks. Muzzle loading guns and a variety of pistols are also made. ¨ The Nagas make their earthen pots without a wheel. Pots are produced by a few select villages. Exclusively a woman's craft, the pots are shaped by hands; the wheel is not used. The women make plain round earthen cooking pots with flattened out-turned rims. A good sticky light-brown clay mixed with red and grey clay which has been allowed to season for a year is usually used. Most of the pots are made for use at home and their sizes vary according to the use to which they are put. The firing of the pots is done outside the village, either at the sunset hour or early in the morning and precautions are taken against the outbreak of fire.

Tribal craft covers diverse areas: ¨ The Nagas decorate even the most deadly weapons of warfare -- their daos and spears are decorated with hair dyed bright red with manjit and blue from indigo. ¨ The jewellery used by Naga women is simple. Necklaces of beads of cornelian, grass, turned wood beads, silver, and cowries are used. The stones and beads are usually imported but the workmanship is entirely local. ¨ Blacksmithy is a relatively new craft which began after the 18th century. Konyaks are experts at this. In the olden days, tradition required a Naga smith to observe food restrictions while at work; this is no applicable. Agricultural implements like the dao, axe, hoe, scraper, and sickle, and weapons like spear heads, butts, arrow heads, and muskets, as well as ornamental spears for dancing, are all crafted locally by the Konyaks. Muzzle loading guns and a variety of pistols are also made. ¨ The Nagas make their earthen pots without a wheel. Pots are produced by a few select villages. Exclusively a woman's craft, the pots are shaped by hands; the wheel is not used. The women make plain round earthen cooking pots with flattened out-turned rims. A good sticky light-brown clay mixed with red and grey clay which has been allowed to season for a year is usually used. Most of the pots are made for use at home and their sizes vary according to the use to which they are put. The firing of the pots is done outside the village, either at the sunset hour or early in the morning and precautions are taken against the outbreak of fire.

Tribal Jewellery of Kutch, Gujarat,

Traditional tribal jewelry remains an integral part of village dress. Each silversmith specializes in a type of jewelry that embodies a particular community's traditional design. The jewelers and the communities with whom they work have strong relationships since they have lived and worked together for generations. Kachchh silver is known for its white quality which resists tarnish. Artisans use brightly colored glass called meena to accentuate traditional designs.

Traditional tribal jewelry remains an integral part of village dress. Each silversmith specializes in a type of jewelry that embodies a particular community's traditional design. The jewelers and the communities with whom they work have strong relationships since they have lived and worked together for generations. Kachchh silver is known for its white quality which resists tarnish. Artisans use brightly colored glass called meena to accentuate traditional designs.

Tribal Jewellery Of Odisha,

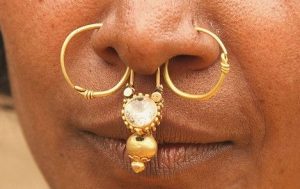

Odisha is an abode to many tribes and their traditional art forms. They show excellent skill and mastery in using alluminium, brass, silver, wood and beads to make their ornamental jewellery. Their jewellery is associative of their ritualistic and religious belief. Some of the jewellery worn by tribal people of Orissa are:

Odisha is an abode to many tribes and their traditional art forms. They show excellent skill and mastery in using alluminium, brass, silver, wood and beads to make their ornamental jewellery. Their jewellery is associative of their ritualistic and religious belief. Some of the jewellery worn by tribal people of Orissa are:

- Bonda tribal women are nude, they wear only short skirts and cover their breasts with beads necklaces and wear brass and aluminium rings piled over one another around their neck. They also wear a coin necklace called Dabulubeida.

- Kondh women wear three rings in their nose and men wear two rings in their nose. Women adorn their hair with several hairpins called sipna made of copper, brass and silver. The sipna are in shape of scissors. It is put on the back of women’s head.

- Ahali hara is a necklace made of coins (mostly 50 paise and 1 rupee) strung through holes punched in the coins.

- Kiyu murmas are set of small silver or gold rings worn in the ear

- Gond tribal women of Nabarngpur district wear silver bangles with beautiful designs etched over them. Sometimes the design is made with spikes. It is to adorn their beauty as well as for their safety. These beautiful bangles are crafted by local smiths.

- Saura women wear big wooden discs in their ears.

- Gadaba women are fond of wearing brass and aluminium jewellery. Gadaba males also wear rings in their fingers. Women wear big rings around their neck called Khagla which are heavy in weight. They also wear copper wire ear hoops.

- Santal tribal women wear silver wristlet.

Tribal Kaudi/Cowrie Work of Chattisgarh,

Cowrie symbolises with Goddess Lakshmi and thus prosperity and wealth to the tribals of Chhatisgarh. Irkipal village four kilometres from the Tokapal is a small habitat of Banajara tribals who embroider bright coloured clothes in cowrie and shell work. The cowrie embellished items are then used like waistbands, baskets, caps, garments for women, armbands etc. The tribals freely experimenting with the usage of cowrie on all variety of textiles have also used it on the bison Maria headgear.

Cowrie symbolises with Goddess Lakshmi and thus prosperity and wealth to the tribals of Chhatisgarh. Irkipal village four kilometres from the Tokapal is a small habitat of Banajara tribals who embroider bright coloured clothes in cowrie and shell work. The cowrie embellished items are then used like waistbands, baskets, caps, garments for women, armbands etc. The tribals freely experimenting with the usage of cowrie on all variety of textiles have also used it on the bison Maria headgear.

Tribal Metal Bells/Ghungroos of Jharkhand,

Metal casting is done by the community of nomadic craftsmen called Malhores, who move from place to place collecting old brass scrap and casting images of gods and goddesses and other utility items such as vessels, diyas/oil lamps, anklets and bells used by tribal communities.

Metal casting is done by the community of nomadic craftsmen called Malhores, who move from place to place collecting old brass scrap and casting images of gods and goddesses and other utility items such as vessels, diyas/oil lamps, anklets and bells used by tribal communities.

Tribal Textile Weaving of Chattisgarh,

The textiles here are woven in a heavy cotton with a count of between 10 and 20. The pallu and border are detailed in natural colours of terracotta and brown derived from Indian Madder, and black from rusted iron. Saris are now also being woven in finer counts for the urban market. Innovations include a mixed weave combining cotton and tussar. Their dramatic yet simple designs have very contemporary appeal. The tribal weaves of Bastar are woven on manual looms. This process can be dated to before the 16th century. The textiles have designs of animals, birds, huts, bows, arrows, plants, peacocks, tribal flowers, pitchers, temples, and lions woven on them. These fabrics are worn by the tribals on the occasion of festivals, dances, and marriages.

The textiles here are woven in a heavy cotton with a count of between 10 and 20. The pallu and border are detailed in natural colours of terracotta and brown derived from Indian Madder, and black from rusted iron. Saris are now also being woven in finer counts for the urban market. Innovations include a mixed weave combining cotton and tussar. Their dramatic yet simple designs have very contemporary appeal. The tribal weaves of Bastar are woven on manual looms. This process can be dated to before the 16th century. The textiles have designs of animals, birds, huts, bows, arrows, plants, peacocks, tribal flowers, pitchers, temples, and lions woven on them. These fabrics are worn by the tribals on the occasion of festivals, dances, and marriages.

Tribal Textile Weaving of Tripura,

Tripura derives its name from the single largest tribe of the state, the Tripuris. Apart from the hill tribes, Tripura has a large Bengali community settled in the plains around Agartala. Like the other states of the Northeast, weaving is a predominantly a woman's activity but in the plains, men are professional weavers and weaving is done as a commercial activity. Tripura has a traditional cloth called the riha, which is worn by the women and covers the upper half of the body. The background of the riha is usually blue-black but can sometimes be red. The cloth generally has vertical and horizontal stripes with scattered motifs in different colours. The patterns could be stars, dots, stylised floral motifs, or the special designs of the tribe. Tripura has a rich heritage of designs that vary from tribe to tribe, each tribe or community having its own specific designs and motifs for weaving shawls and sarongs. It is said that in Tripura legends are sung and woven into the fabric. Besides the riha, women wear and weave lungis, saris and chaddars. Colours are symbolic and, hence, significant. The worst punishment a weaver can get is to be forbidden the use of a colour or colours. The Riang tribe of Tripura uses natural dyes for the black, blue, and brown. The blue, black, and brown yarns are of hand-spun cotton and dyed with colours obtained from plants. Only the white yarn is mill-spun cotton. In many parts of the state, cotton yarn is being replaced by rayon. A special mention may be made of the popular and intricate cloth called the lasingphee, in which the cloth is wadded with cotton during weaving. This thick and warm cloth is used for quilts, covers, scarves and bedspreads. Shawl is a seasonal garment used in winter and is woven on loin loom. Woven in traditional design with ethnic look. shawl is made with cotton yarn dyed in natural colours only.

Tripura derives its name from the single largest tribe of the state, the Tripuris. Apart from the hill tribes, Tripura has a large Bengali community settled in the plains around Agartala. Like the other states of the Northeast, weaving is a predominantly a woman's activity but in the plains, men are professional weavers and weaving is done as a commercial activity. Tripura has a traditional cloth called the riha, which is worn by the women and covers the upper half of the body. The background of the riha is usually blue-black but can sometimes be red. The cloth generally has vertical and horizontal stripes with scattered motifs in different colours. The patterns could be stars, dots, stylised floral motifs, or the special designs of the tribe. Tripura has a rich heritage of designs that vary from tribe to tribe, each tribe or community having its own specific designs and motifs for weaving shawls and sarongs. It is said that in Tripura legends are sung and woven into the fabric. Besides the riha, women wear and weave lungis, saris and chaddars. Colours are symbolic and, hence, significant. The worst punishment a weaver can get is to be forbidden the use of a colour or colours. The Riang tribe of Tripura uses natural dyes for the black, blue, and brown. The blue, black, and brown yarns are of hand-spun cotton and dyed with colours obtained from plants. Only the white yarn is mill-spun cotton. In many parts of the state, cotton yarn is being replaced by rayon. A special mention may be made of the popular and intricate cloth called the lasingphee, in which the cloth is wadded with cotton during weaving. This thick and warm cloth is used for quilts, covers, scarves and bedspreads. Shawl is a seasonal garment used in winter and is woven on loin loom. Woven in traditional design with ethnic look. shawl is made with cotton yarn dyed in natural colours only.

Tribal Textiles of Arunachal Pradesh,

Most tribes in Arunachal Pradesh have a tradition of weaving which is done solely by the women on single-neddle tension or on loin-looms which have a warp of some 6 yards x 18 inches. The woven fabric is thick as the warp is dense and usually covers the weft. The colours and designs are symbolic of the rituals and customs of each tribe and community. The women are very careful about the colours and designs they use while weaving the cloth. Combinations of black, red, and white are prominent, and bold stripes are woven into the fabric by making use of different coloured yarns in the warp. Colours are obtained from natural sources such as the barks, roots, leaves, and seeds of trees and are used alongside synthetic dyes and chemicals. The design may vary from a formal arrangement of lines and bands of colour to elaborate woven patterns in yellows, greens, and scarlet. Generally patterns are symmetrical, as more than one width of the woven fabric is needed to make a garment. Many tribes use special methods for decorating. Woven items include Tudung jackets and shawls of the Sherdukpans, Monpa bags, Apa Tani jackets and scarves, Adi skirts (galle), jackets, bags, and scarves, Mishmi jackets, shawls, bags, and blouses, Wancho bags, loin cloths, and sashes, and Tangsa lungis and bags. Further north, the Monpas, Membas, and Bokers weave woollen jackets, trouser lengths, and blankets.

Most tribes in Arunachal Pradesh have a tradition of weaving which is done solely by the women on single-neddle tension or on loin-looms which have a warp of some 6 yards x 18 inches. The woven fabric is thick as the warp is dense and usually covers the weft. The colours and designs are symbolic of the rituals and customs of each tribe and community. The women are very careful about the colours and designs they use while weaving the cloth. Combinations of black, red, and white are prominent, and bold stripes are woven into the fabric by making use of different coloured yarns in the warp. Colours are obtained from natural sources such as the barks, roots, leaves, and seeds of trees and are used alongside synthetic dyes and chemicals. The design may vary from a formal arrangement of lines and bands of colour to elaborate woven patterns in yellows, greens, and scarlet. Generally patterns are symmetrical, as more than one width of the woven fabric is needed to make a garment. Many tribes use special methods for decorating. Woven items include Tudung jackets and shawls of the Sherdukpans, Monpa bags, Apa Tani jackets and scarves, Adi skirts (galle), jackets, bags, and scarves, Mishmi jackets, shawls, bags, and blouses, Wancho bags, loin cloths, and sashes, and Tangsa lungis and bags. Further north, the Monpas, Membas, and Bokers weave woollen jackets, trouser lengths, and blankets.

Tribal Textiles of Nagaland,

In Nagaland, cotton is found in abundance and so is the skill to make the textiles. The Naga methods of processing, spinning, and weaving cotton are simple but the motifs, designs and patterns that are woven on to the cloth are complex. Traditional shawl-weaving is done by the women on narrow loin-looms, while other fabrics are woven on the fly shuttle. Nagaland is home to several tribes. Each tribe uses bold distinctive patterns with simple clean lines, stripes, squares, and bands and has its own specific designs and motifs for shawls and sarongs. Common colours are black or white with red and green motifs for introducing an extra weft. The combinations and the designs have tremendous social significance and symbolic meaning. The dress a person wears reveals his/her standing in the tribal hierarchy. Men are allowed to wear certain patterns and colours only after establishing a record of feats and achievements. Within each tribe, there is a distinction between classes on the basis of the shawls they wear. Elaborately designed shawls are used by the warrior classes or the rich segments within the tribe. A Naga shawl is the most important part of the dress and is woven with cotton and staple fibre, though some wool is used. Shawls vary from simple white ones to elaborately designed ones with symbols and colours. The same is true for skirts in which mainly red woollen yarn is used. Shawls are woven in three pieces and then stitched together. The central strip has more ornamentation than the borders, which usually have the same pattern. The tsung kotepsu has a white woven band stitched along the centre of the shawl and is woven over with figures of elephants, tigers, mithuns, cocks, and circles, representing human heads. It has horizontal black, red, or white stripes. A rich and brave man's acquisitions and achievements are picturised on it. The lotha naga shawl is woven in nine parts and stitched together. Many traditions and beliefs are associated with the weaving and wearing of the traditional dress. When a chang cloth is worn care is supposed to be taken to see that all the zig-zag lines fall uniformly, or else the young warrior may die a premature death. When a Konyak woman gets married she wears a shatni shawl which is preserved and used only to wrap her dead body. Convention demands that a rongtu shawl be worn only if the mithun sacrifice has been conducted over three generations. Textile dyeing is a significant art among the hill tribes of the region. Each tribe possesses one or two good dyes. Superstition and belief also back the selection of colour. Red symbolises blood and the people in this region believe that if a young woman dyes her cloth red, she is sure to die a violent death. Thus only old women dye yarn red. Blue dye is made by boiling indigo in a huge pot in which the clothes or thread to be dyed are dipped and boiled for nearly an hour. Then, these are taken out and dried in the sun and the process is repeated until each cloth takes on the desired tinge. Textile dress material is called pulusi and is woven by women, deriving designs from graphs. The dress material, noted for its striking colours, is being accepted as fashionable wear in other parts of the country. Kamphie is a rengma traditional dress of Naga women. The collection of raw material for this as well as the dyeing of thread is celebrated as a festival during the first week of December. When the dyeing process is completed, the dress is begun. It takes nearly one mouth to complete. The colour combination in the kamphie is usually red, white, green, yellow, and black. This is used only in marriages and in the rengma festival of Nagada. This is an age-old process which continues till today.

In Nagaland, cotton is found in abundance and so is the skill to make the textiles. The Naga methods of processing, spinning, and weaving cotton are simple but the motifs, designs and patterns that are woven on to the cloth are complex. Traditional shawl-weaving is done by the women on narrow loin-looms, while other fabrics are woven on the fly shuttle. Nagaland is home to several tribes. Each tribe uses bold distinctive patterns with simple clean lines, stripes, squares, and bands and has its own specific designs and motifs for shawls and sarongs. Common colours are black or white with red and green motifs for introducing an extra weft. The combinations and the designs have tremendous social significance and symbolic meaning. The dress a person wears reveals his/her standing in the tribal hierarchy. Men are allowed to wear certain patterns and colours only after establishing a record of feats and achievements. Within each tribe, there is a distinction between classes on the basis of the shawls they wear. Elaborately designed shawls are used by the warrior classes or the rich segments within the tribe. A Naga shawl is the most important part of the dress and is woven with cotton and staple fibre, though some wool is used. Shawls vary from simple white ones to elaborately designed ones with symbols and colours. The same is true for skirts in which mainly red woollen yarn is used. Shawls are woven in three pieces and then stitched together. The central strip has more ornamentation than the borders, which usually have the same pattern. The tsung kotepsu has a white woven band stitched along the centre of the shawl and is woven over with figures of elephants, tigers, mithuns, cocks, and circles, representing human heads. It has horizontal black, red, or white stripes. A rich and brave man's acquisitions and achievements are picturised on it. The lotha naga shawl is woven in nine parts and stitched together. Many traditions and beliefs are associated with the weaving and wearing of the traditional dress. When a chang cloth is worn care is supposed to be taken to see that all the zig-zag lines fall uniformly, or else the young warrior may die a premature death. When a Konyak woman gets married she wears a shatni shawl which is preserved and used only to wrap her dead body. Convention demands that a rongtu shawl be worn only if the mithun sacrifice has been conducted over three generations. Textile dyeing is a significant art among the hill tribes of the region. Each tribe possesses one or two good dyes. Superstition and belief also back the selection of colour. Red symbolises blood and the people in this region believe that if a young woman dyes her cloth red, she is sure to die a violent death. Thus only old women dye yarn red. Blue dye is made by boiling indigo in a huge pot in which the clothes or thread to be dyed are dipped and boiled for nearly an hour. Then, these are taken out and dried in the sun and the process is repeated until each cloth takes on the desired tinge. Textile dress material is called pulusi and is woven by women, deriving designs from graphs. The dress material, noted for its striking colours, is being accepted as fashionable wear in other parts of the country. Kamphie is a rengma traditional dress of Naga women. The collection of raw material for this as well as the dyeing of thread is celebrated as a festival during the first week of December. When the dyeing process is completed, the dress is begun. It takes nearly one mouth to complete. The colour combination in the kamphie is usually red, white, green, yellow, and black. This is used only in marriages and in the rengma festival of Nagada. This is an age-old process which continues till today.