Idol Making of Rajasthan,

Idol making is craft practiced in the regions of Jaipur, Alwar, Sikandra, Manpur and Dausa. Marble is sourced from Makrana, Bhainslana and Jhirri. Objects such as idols of gods and goddesses, stands on which the idols are placed, portrait busts etc are made under this craft-form. Tools such as hammer, chisel, chapti- tool used for smoothening the stone, patti- stone used for polishing, guniya- right angle, prakaar- divider, drill, files and emery etc are used for crafting process.

Idol making is craft practiced in the regions of Jaipur, Alwar, Sikandra, Manpur and Dausa. Marble is sourced from Makrana, Bhainslana and Jhirri. Objects such as idols of gods and goddesses, stands on which the idols are placed, portrait busts etc are made under this craft-form. Tools such as hammer, chisel, chapti- tool used for smoothening the stone, patti- stone used for polishing, guniya- right angle, prakaar- divider, drill, files and emery etc are used for crafting process.

Idu Mishmi Textiles of Arunachal Pradesh,

Arunachal Pradesh has a rich textile heritage, which is now being threatened by the onslaught of modernization and industrialization. Textiles made by the Idu Mishmi, a sub-tribe of the Mishmi tribe, are prized possessions,usually woven by the women of the community to supplement the family income. Weaving is a traditional occupation for the women, and the fabrics they produce are of symbolic significance to their customs and practices. Today however, synthetic yarns are being excessively used instead of cotton, because they are easily available. Often artists use a blend of natural and acrylic yarns to create a textural symphony. The community associations and organizations are promoting the use of natural fibres along with a combinationof different techniques.v

Arunachal Pradesh has a rich textile heritage, which is now being threatened by the onslaught of modernization and industrialization. Textiles made by the Idu Mishmi, a sub-tribe of the Mishmi tribe, are prized possessions,usually woven by the women of the community to supplement the family income. Weaving is a traditional occupation for the women, and the fabrics they produce are of symbolic significance to their customs and practices. Today however, synthetic yarns are being excessively used instead of cotton, because they are easily available. Often artists use a blend of natural and acrylic yarns to create a textural symphony. The community associations and organizations are promoting the use of natural fibres along with a combinationof different techniques.v

Ikat/Bandha of Gujrat,

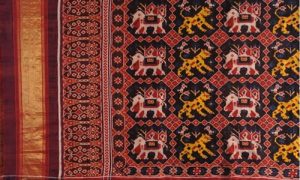

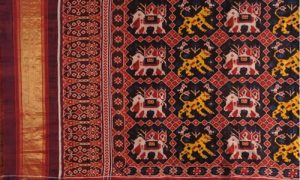

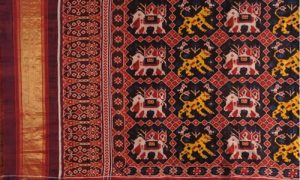

The marvelous and striking Odishan (Orissan) made from cotton and silk ikat is known as bandha. These generally include ikat motifs of flowers, stars, fish and large motifs depicting elephants and parrots. Apart from these zoomorphics, abstract patters are also made such as the wave and geometrical patterns. At times bandha ikat is produced with brocades to give a metallic finish that makes the borders glimmer. This kind of pattern is mostly produced in Sonipur, Gujarat. Dyes of colours such as magenta, red, yellow, green are used to match with the ikat pattern.

The marvelous and striking Odishan (Orissan) made from cotton and silk ikat is known as bandha. These generally include ikat motifs of flowers, stars, fish and large motifs depicting elephants and parrots. Apart from these zoomorphics, abstract patters are also made such as the wave and geometrical patterns. At times bandha ikat is produced with brocades to give a metallic finish that makes the borders glimmer. This kind of pattern is mostly produced in Sonipur, Gujarat. Dyes of colours such as magenta, red, yellow, green are used to match with the ikat pattern.

Ikat/Bandha/Yarn Tie-Dye of Odisha,

Ikat or bandha of Odisha has gloriously woven, blurred, and gem-coloured motifs in silk and cotton. The dominant motifs in this craft include animals and birds, with the traditional designs being fish and conch shell as well as bolmala, chandankora, and sachipar. As the design-type is single ikat, the designs on the material are blurred; however, this trace-design has a beauty all its own. The intricate process involves tie and dye --- knotting sections of the yarn before dipping them in colours one at a time, and finally weaving them to produce motifs in multi-hued tones. While Sambalpur is famous for its double-ikat textiles, Sonepur is known for its gold embroidered ones.

Ikat or bandha of Odisha has gloriously woven, blurred, and gem-coloured motifs in silk and cotton. The dominant motifs in this craft include animals and birds, with the traditional designs being fish and conch shell as well as bolmala, chandankora, and sachipar. As the design-type is single ikat, the designs on the material are blurred; however, this trace-design has a beauty all its own. The intricate process involves tie and dye --- knotting sections of the yarn before dipping them in colours one at a time, and finally weaving them to produce motifs in multi-hued tones. While Sambalpur is famous for its double-ikat textiles, Sonepur is known for its gold embroidered ones.

Ikat/Patola Sari Weaving of Ahmedabad, Gujarat,

Patola design originates from the town of Patan, Gujarat which utilises double-ikat pattern to create beautiful textile pieces. They traditionally resist-dyed with natural dyes and then woven. The Salvi family of Patan is the only one that continues to practice this craft in Patan. This skill has been handed down to them over several generations. Making a Patola sari is a complex process and the weaving process is painstaking. The designs have been mastered over the years. Single ikat Patola saris are less intricate and are mainly produced in Surendranagar and Rajkot.

Patola design originates from the town of Patan, Gujarat which utilises double-ikat pattern to create beautiful textile pieces. They traditionally resist-dyed with natural dyes and then woven. The Salvi family of Patan is the only one that continues to practice this craft in Patan. This skill has been handed down to them over several generations. Making a Patola sari is a complex process and the weaving process is painstaking. The designs have been mastered over the years. Single ikat Patola saris are less intricate and are mainly produced in Surendranagar and Rajkot.

Ikat/Patola Weaving of Rajkot, Gujarat,

A less meticulous and more affordable counterpart to the traditional Patan Patola, Rajkoti Patola is characterized by its cheaper raw materials and single ikat weave. In the single ikat technique, weavers first tie and dye the warp according to the planned design and then entwine the prepared threads with a plain weft producing vibrant geometric motifs in the finished weave. Rajkoti Patola is produced in Surendranagar and Rajkot. Rajkot Patola is an ancient traditional weave, today famously produced in the Rajkot and Surendranagar districts of Gujarat. Rajkot Patola sarees have a distinctive style of production and preparation that is different to other forms of Patola sarees. Unlike the others, these are single-ikat sarees woven on silk, indigenous to Rajkot. The community of artisans and weavers has perpetuated this craft for 800 years. These sarees use zari on the pallu, bodice or the border. Unique motifs inspired from nature, such as parrots, flowersand elephants, are woven on them. Inspiration is also derived from the lifestyles of local communities.

A less meticulous and more affordable counterpart to the traditional Patan Patola, Rajkoti Patola is characterized by its cheaper raw materials and single ikat weave. In the single ikat technique, weavers first tie and dye the warp according to the planned design and then entwine the prepared threads with a plain weft producing vibrant geometric motifs in the finished weave. Rajkoti Patola is produced in Surendranagar and Rajkot. Rajkot Patola is an ancient traditional weave, today famously produced in the Rajkot and Surendranagar districts of Gujarat. Rajkot Patola sarees have a distinctive style of production and preparation that is different to other forms of Patola sarees. Unlike the others, these are single-ikat sarees woven on silk, indigenous to Rajkot. The community of artisans and weavers has perpetuated this craft for 800 years. These sarees use zari on the pallu, bodice or the border. Unique motifs inspired from nature, such as parrots, flowersand elephants, are woven on them. Inspiration is also derived from the lifestyles of local communities.

Ikat/Patola Weaving of Surendranagar, Gujarat,

The procedure for making a Patola is extremely delicate and time-consuming. The Patola from Patan is made using a double ikat technique. To cater to more lovers of Patola, a simpler version with a lower price range was invented. The Surendranagar technique uses ikat on only one side. The Single Ikat Patola of Surendranagar and neighboring villages came to the rescue of the weavers.

The procedure for making a Patola is extremely delicate and time-consuming. The Patola from Patan is made using a double ikat technique. To cater to more lovers of Patola, a simpler version with a lower price range was invented. The Surendranagar technique uses ikat on only one side. The Single Ikat Patola of Surendranagar and neighboring villages came to the rescue of the weavers.

Ilkal Sari Weaving of Karnataka,

Ilkal is an expensive saree from Karnataka state. Its characteristic is the joining of the body warp with the pallu warp, which is locally known as “tope teni”. The technique is used exclusively for Ilkal Sarees. Warp threads for the body, border and pallu are prepared separately. The colour of the border and pallu warp are the same whereas the body warp is in a contrasting colour. The saree is woven on traditional pit/frame looms fitted with the dobby/jacquard mechanism.

Ilkal is an expensive saree from Karnataka state. Its characteristic is the joining of the body warp with the pallu warp, which is locally known as “tope teni”. The technique is used exclusively for Ilkal Sarees. Warp threads for the body, border and pallu are prepared separately. The colour of the border and pallu warp are the same whereas the body warp is in a contrasting colour. The saree is woven on traditional pit/frame looms fitted with the dobby/jacquard mechanism.

Incense, Dhoop Rolls and Dhun Sticks

Hindus and Buddhists across the length and breadth of Nepal offer oblations and prayers to the gods and seek their blessings by burning incense. According to Nepalese religious traditions, there are five articles (panchopachar) that are essential in any act of religious worship: dhoop is one of the articles that is an essential part of the offering to the deity. In Nepal a large and varied variety of dhoop is available - it is believed that each one of these varieties possesses its own unique virtues, carries its own particular blessings, and has its own medicinal properties. Ancient manuscripts describe many varieties of dhoop. Special kinds of dhoops are said to possess the power of curing diseases, casting out evil spirits, invoking the nagas (deities) that control the rain-bearing clouds, and invoking Laxmi, the goddess of wealth and fortune.

Hindus and Buddhists across the length and breadth of Nepal offer oblations and prayers to the gods and seek their blessings by burning incense. According to Nepalese religious traditions, there are five articles (panchopachar) that are essential in any act of religious worship: dhoop is one of the articles that is an essential part of the offering to the deity. In Nepal a large and varied variety of dhoop is available - it is believed that each one of these varieties possesses its own unique virtues, carries its own particular blessings, and has its own medicinal properties. Ancient manuscripts describe many varieties of dhoop. Special kinds of dhoops are said to possess the power of curing diseases, casting out evil spirits, invoking the nagas (deities) that control the rain-bearing clouds, and invoking Laxmi, the goddess of wealth and fortune.

PROCESS

A centuries old craft, dhoop-making is still commonly practised all over Nepal by women artisans and home based workers who utilise their leisure hours in twisting papers for the making of the dhoop. All the ingredients of the dhoop powder are readily available in the local markets or are sourced from nearby fields and forests.

Dhoop is made by rolling powdered herbal incenses into long paper strips. Thin sheets of locally produced Daphne bark (lokta) paper is cut into long strips, the length of the strips depending on the length of the requisite incense roll to be made. The dhoop roll can range from 5 to 6 inches in length to 2 to 3 feet. The longer dhoops naturally burn for a greater duration.

The basic process followed in making dhoops is similar, though many individual variations exist. The herbs to be used are first sun-dried; after all their moisture has been removed, they are pounded in a mortar. The mixture thus obtained is then sieved several times, resulting in a very fine powder. Next, paper strips of the required length are taken and the powder is uniformly spread in the middle of the paper strip. The paper strip is twisted into a thin roll, tightly encasing the powder, to create a dhoop roll.

MATERIALS & VARIETIES

Herbs and roots such as dhupi (Juniperus recurva), jatamasi (Nardostachys Jaramansi), the roots of the jasmine plant, kasturi or musk, anguru, manashila, gorochan, sandalwood, and red sandalwood (rakta chandan) are some of the ingredients of which dhoop is made.

- The most common dhoop, used in most worship is made from dhupi (Juniperus recurva), jatamashi (Nardostachys Jaramansi), and the roots of the jasmine plant.

- The pancha sugandha dhoop or five-fold incense is specially used for worshipping different deities. It is composed of equal parts of five (pancha = five) items: sandalwood, musk, kumkum, keshari, and anguru.

- The astagandha dhoop or eight-fold incense is burnt for invoking the deities on special occasions. This particular incense is supposed to bring peace and prosperity by driving away evil spirits. As its name suggests (asta = eight) it is composed of eight ingredients - sandalwood, red sandalwood or rakta chandan, saldhup, camphor, keshar, anguru, kasturi, and gungu. The ingredients are pulverised, mixed together, and made into incense rolls.

- The laxmi dhoop is believed to possessthe power to banish poverty and bring wealth and good luck to the family. The composition of this incense includes the addition of the laxmi flower and gungu to the pancha sugandha dhoop.

- The naga (or serpent) dhoop is based on the religious conviction that when this incense is burnt, the naga deity is invoked. As the nag is associated with rain, this incense is supposed to cause rain and remove drought. Whenever any stone fountain, well, or spring is constructed, this incense is burnt to invoke the naga.

- In Nepalese society, witchcraft is a belief that is still prevalent; the man who fights and drives away the witch is known as jhankri (i.e., a witch physician). If a person is troubled by a witch, a special kind of incense is burnt: this is called bokshi dhoop or the witch incense. It consists of upturned chillies, skin of snakes, and the (black) seeds of the lankashani plant (a plant with a white flower and black seeds). All the above ingredients are dried and powdered. When it is believed that a person is possessed by a witch, this incense is burnt; when burnt in the fire, the bokshi dhoop is supposed to releases forces that drive away the witch.

- Prolonged illness is attributed to the presence of an evil spirit haunting the house. In such cases, the sik vayu dhoop (ghost or spirit incense) is burnt; it is supposed to bring relief to the patient by driving away the evil spirit.

In Nepal the science of aromatherapy and the healing power of herbs is well known and utilised. However systematic research and documentation of this ancient knowledge and lore needs to be undertaken before it is lost.

DHUN STICKS

A variety of incense called dhun in Newari is made by the Tibetans. This does not require paper strips. The Tibetans collect specific fragrant herbs and pulverise them. They make the herb powders into pastes and smear the pastes uniformly on long sticks, which are then burnt during prayer.

Indian Cork/Kuhila Koth of Assam,

Kuhila koth (Indian cork), fiber weaving, is one of the main handicrafts of the Batadrava area of Nowgong district and is also considered a major cottage industry in Gauripur area of Dhubri district in Lower Assam. Kuhila is cultivated in the low-lying, marshy areas. The portion that remains below the water is utilised. The fibrous outer covering is scraped with a knife and then dried in the sun. It is then cut lengthwise into smaller pieces, which are then woven on a simple loom-like gadget made of wood and bamboo poles.

The first kuhila koth in Assam is said to be made by Mohapurush Madhavdev. The items produced today include seats, mats, and cushions.

Iron Craft of Rajasthan,

The blacksmiths of Rajasthan are called lohars from the term loha meaning iron. The Hindu blacksmiths are divided into broad groups --- gadias and the malwias. The gadias move from village to village repairing farm tools and making items of everyday use. They consider Chittorgarh as their place of origin and are Vaishnav followers of Ramdev Pir. The malwia lohars claim Malwa in Madhya Pradesh as their place of origin. They are Shaivites by religion and worship Goddess Shakti and a few other local goddesses. Some of the items made of iron are ovens which are square or octagonal in shape with parrot or peacock-shaped legs and perforated walls. These are used to heat temples and homes in winter. Sigris or ovens with chains, and mobile ones with wheels also serve this purpose. These have burning coals in them and are carried to whichever part of the house they are needed in. The other item is the nut-cracker with an iron cutting edge. The shapes given to nut-crackers include birds, animals, and amorous couples. The iron craft practised in Jaisalmer and Tillonia is done by way of twisting iron wires and cutting the sheets. The main products are animal figures, decorative kitchen ware, and stands.

The blacksmiths of Rajasthan are called lohars from the term loha meaning iron. The Hindu blacksmiths are divided into broad groups --- gadias and the malwias. The gadias move from village to village repairing farm tools and making items of everyday use. They consider Chittorgarh as their place of origin and are Vaishnav followers of Ramdev Pir. The malwia lohars claim Malwa in Madhya Pradesh as their place of origin. They are Shaivites by religion and worship Goddess Shakti and a few other local goddesses. Some of the items made of iron are ovens which are square or octagonal in shape with parrot or peacock-shaped legs and perforated walls. These are used to heat temples and homes in winter. Sigris or ovens with chains, and mobile ones with wheels also serve this purpose. These have burning coals in them and are carried to whichever part of the house they are needed in. The other item is the nut-cracker with an iron cutting edge. The shapes given to nut-crackers include birds, animals, and amorous couples. The iron craft practised in Jaisalmer and Tillonia is done by way of twisting iron wires and cutting the sheets. The main products are animal figures, decorative kitchen ware, and stands.

Ivory Craft,

Ivory has always been a scarce commodity - not more than one in a hundred Sri Lankan male elephants have tusks. However, now that the elephant is a protected animal at Sri Lanka it is almost impossible for the artisans to legitimately obtain ivory to pursue their craft. Ivory-carvers are using other materials like horn and bone as a base for their craft: it is difficult, however, to replicate the high density of texture and delicacy of tint that ivory possesses in bone, horn, and other materials used instead of ivory. Ivory is, and has always been, a rare and costly material. The Chadanta Jataka, a part of Sri Lankan folk-lore records a tale of the suffering and subsequent death of a great elephant that was robbed of its tusks; this was considered to be a great sin. Therefore, in traditional Sri Lanka, no elephant was supposed to be killed for the ivory. The craft is found dominantly in the village of Kekirawa in Anuradhapura district; in Galle district in the south of the island-country, ivory cutting is found in the village of Galwadugoda. It is commonly practised by the artisans who have descended from families that have nurtured the craft for generations and preserved its heritage.

Ivory has always been a scarce commodity - not more than one in a hundred Sri Lankan male elephants have tusks. However, now that the elephant is a protected animal at Sri Lanka it is almost impossible for the artisans to legitimately obtain ivory to pursue their craft. Ivory-carvers are using other materials like horn and bone as a base for their craft: it is difficult, however, to replicate the high density of texture and delicacy of tint that ivory possesses in bone, horn, and other materials used instead of ivory. Ivory is, and has always been, a rare and costly material. The Chadanta Jataka, a part of Sri Lankan folk-lore records a tale of the suffering and subsequent death of a great elephant that was robbed of its tusks; this was considered to be a great sin. Therefore, in traditional Sri Lanka, no elephant was supposed to be killed for the ivory. The craft is found dominantly in the village of Kekirawa in Anuradhapura district; in Galle district in the south of the island-country, ivory cutting is found in the village of Galwadugoda. It is commonly practised by the artisans who have descended from families that have nurtured the craft for generations and preserved its heritage.

HISTORY & TRADITIONS: A PRESTIGIOUS MEDIUM

Often, ivory is not used by the Hindus for making images of gods and goddesses as the belief is that animal products are not to be used for religious or auspicious purposes. The Buddhists who are found in a majority in Sri Lanka do not share this belief: exquisite and intricate ivory-carving is found very widely in Sri Lanka. Large tusks are highly valued and form part of the treasures of viharas or mansions and devales or temples. The image of a pair of tusks placed on either side of the doorways of temples is an evocative one in the annals of Sri Lankan history.

Visual and written documentation indicates that, traditionally, ivory work was patronised by royalty and the wealthy. Given the scarcity of the material and the degree of skill required to work with it, it is not surprising that ivory acquired the character of a prestigious medium. The ivory-carver occupied an important position in the mediaeval society of Sri Lanka and has the status of a mastercraftsman in one of four guilds or royal workshops to which the best goldsmiths, silversmiths, painters, and ivory-carvers of the land were attached. These artisans, who 'worked only for the king', secured this prestigious position by displaying extraordinary skill and versatility.

1. THE TRADITIONAL PRODUCT RANGE

The product range, even traditionally, included an amalgam of utilitarian and artistic, from intricately carved tooth-picks to magnificently carved caskets. Semi-historical records refer to the use of ivory for decorating shrines, buildings, and parks. Exquisitely carved plaques and panels are also found in ancient monuments, highlighting the value of ivory-carving as a means of ornamentation that was not merely beautiful but also enduring. Places of worship or of religious significance offer beautiful examples of ivory figures as well as intricate ornamentation in ivory. Ivory figures of devas or guardians of the threshold are found at the base of the door-jamb of viharas and devales. Sometimes figures of dancing-girls are also found, as are animal carvings. The figures are usually depicted with elaborate head-dress, robes and jewellery. Though the treatment is fairly stiff and conventional, yet the figures have dignity and beauty. The right hand receives special attention as do the borders framing the figure(s), which have very detailed and elaborate motifs and designs. Prolific amounts of elaborate ivory carvings can be found on the inner sanctuary doors of temples.

2. A HISTORICAL TREASURE TROVE?

The Museums of Colombo and Kandy have large collections of ivory objects belonging to the mediaeval Kandyan period. Among the items on display are small panels which are used to decorate doorways, palanquin railings, large and small boxes, relic caskets, statuettes, fan handles, manuscript covers, combs, bracelets, necklaces, hairpins, knife-handles, styluses, toy-drums and flutes which show off the detailed carving skills of the artisans.

The Colombo Museum also has ivory statuettes of Buddha which appear to have been painted. The figures in ivory are mainly standing and nor seated or reclining. The authoritative treatise Mahavamsa speaks of a park made at Polonnaruva by the King Parakrama Bahu, which was said to be railed 'with pillars decorated with rows of images made of ivory' including ivory-railed palanquins. The king is also said to have built a pavilion wrought with ivory in his 'Island Park'.

A magnificent ivory casket found in the Schatzkammer (Treasure Chamber) of the Residenz Museum in Munich and sent as a tribute from Don Juan Dharmapala, Crown Prince of Sri Lanka, in 1540 AD to the Portuguese king to strengthen the links between Sri Lanka and Portugal deserves special mention. This casket has several panels of bold carving, encrusted with gold and coloured gems.

TECHNIQUES

1. IVORY-CARVING & IVORY-TURNING

The crafts of ivory carving and ivory turning are very different; the ivory carver is a galladda, a multi-faceted craftsman of a high rank who also practises painting and building. The ivory turner belongs to the vaduvo; his work is restricted only to ivory turning. The ivory carver belongs to the high caste group of et-dat-ketayan-karaya; while the ivory turner belongs to a low caste group, known as liyana-vaduva.

Ivory-Turning

Articles made with the lathe include fan handles, handles of knives, implements and tools, boxes, book-buttons, and scent-sprays. They are usually decorated with coloured lac, which is used to fill in the incisions. The dots are made with a pointed tool and the circles are made with compass-like tools having two points, one being stationary and the other describing a circle around that point. Typical turned ivory boxes are used for jewellery and sometimes for medicine.

Ivory-Carving

The tools used by the ivory carver include saws, engravers and chisels. The techniques of carving and ornamentation are based on traditions passed down through generations in families. A very difficult craft to learn, ivory carving usually requires rigorous training under a mastercraftsman.

The principles of ivory-carving share a lot with techniques used in metal and wood carving. The design is first drawn, painstakingly and extremely neatly, on the ivory surface. Curves and circles, depicting the shapes of flowers and foliage, along with lines and dots used to fill in the spaces and enrich the design are meticulously carved. The figures of dancers, sensuous women with rhythmic movements, and mythical and natural animals are also included in the design.

Carving on ivory is done in low-relief with lace-like patterns framed in a small space. Lac is sometimes applied in the cavities for colour and ornamentation. The lac used is usually made from local ingredients like the sap of plants, resins, and mineral dyes, which are mixed to produce basic colours like red, yellow, and black.

THE PRODUCT RANGE

A greatly appreciated souvenir for the affluent tourist to Sri Lanka is a small elephant carved in ivory and decorated with precious metals and jewels: these elephants are usually part of the depiction of the elephant-procession in the Kandy pageant or Perahera held annually at Kandy in honour of the Temple of the Tooth-Relic.

Sinhalese ivory-combs are among the most elaborately carved ivory items; though more severe and less fretted pieces can also be found. The carvings on the combs include an amalgam of figures and plant and geometrical designs. Either both the back and the front are carved with identical design, allowing the comb to face either way, or else the back is left plain. An unfinished ivory comb is known as pana-katuva; the name also applies to a comb in which the teeth are broken or removed. Such combs are repaired by rivetting into a groove a thin strip of ivory cut into new teeth.

Though less frequent now, there is a tradition in Sri Lanka of finely worked book-covers made of ivory. Styluses ( veli-pata) made of ivory were used by the priests in the Pansala schools for teaching writing on sand. Some knives and swords with ivory handles can still be found; increasingly, however, horn has replaced ivory in this respect. Ivory dices, with the numbers represented by lac-filled holes, continue to be an interesting exposition of this craft.

MOTIFS & DESIGNS

1. ANIMAL FORMS

The natural figure of the lion is a commonly used motif among ivory workers; it is said to be the mythical ancestor of the Sinhalese and is believed to represent majesty and power. The lion is portrayed in a variety of different forms and poses. The mythical forms of the lion include the kesara simha, the gaja simha, and nara simha. These are mainly found in the reproductions of the ivory carvings of the Kotte and Kandyan periods, noted for delicacy of line and exquisite detailing.

A traditional motif used in ivory-carving is the serapendiya, a mythical figure of an animal whose head is like that of a lion joined to the body of a bird like the hamsa. This motif is also referred to as the gurulu pakshya. Quite unlike that of the natural lion, the snout of the mythical figure or lion is curled inwards. This motif is common in ivory ear-picks.

Bherunda pakshya, a mythical eagle with two heads, common in paintings and handicrafts of the mediaeval period, is also found in the ivory carvings of the Kandyan period. Hamsa, the divine bird from Hindu mythology is widely found in the ivory-ware of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries - mainly the ivory carvings from the Gampola and Kandyan periods.

2. HUMAN FORMS

Carvings of divine figures with their guardians and attendants flanking them are common in ivory combs. A range of figures - the king in full regalia, the Kandyan chief and the Kandyan ladies, human figures dancing, wrestling, in combat, and performing acrobatic feats - can be found as can depictions of historical events. Ivory combs and ivory caskets are usually superb examples of these expositions. Some of the well-known and oft-depicted motifs are:

- Narikunjara: the combination of several mythical female figures.

- Panch-nari-ghataya: the combination of five youthful female forms to form a pot.

- Catur-nari-pallakkiya: a palanquin of four female forms.

- sapta-nari-turanga: a seven-women horse.

- Nava-nari-kunjaraya: an elephant comprised of nine females.

- Ashtanari rathaya: vehicle of eight females

- Sat-nari-torana: a pandal of six females.