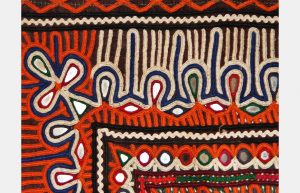

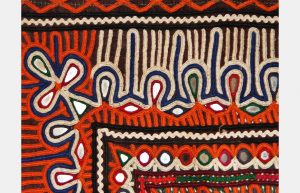

Rabari Embroidery of Kutch, Gujarat,

The Rabari are nomadic tribes that migrated from Rajasthan centuries ago. The Rabari women are known for producing gorgeous and impressive embroidery which is emblematic of their nomadic life. Rabari embroidery is a pictographic representation and symbolic of the mythology, rituals, culture, and life of Rabaris. The Rabaris are subdivided into groups which have distinguishing hand embroidery vocabulary of the composing the chain stitch, the back stitch, and herringbone. Mirrors of all shapes and sizes are liberally utilized. They use codis (beads) and thread fingers to edge the corners. The Rabaris produce native embroidery and garments on a massive scale. Given their nomadic nature, they also believe in ornamenting their cattle and homes. Amongst the Rabaris, men and women have a very different style of traditional wear. The subgroups of Rabaris are distinguished with subtle differences in their traditional attire, weaving and embroidery. Usually, Rabari women can be seen wearing a three-part ensemble consisting of a tubular woollen skirt or a pachhedo along with a backless blouse called kapadun. The men mostly wear a white cotton dhoti. Both the sexes wear jewellery made from silver metals and other ornaments which are mostly crafted by people from their own community.

The Rabari are nomadic tribes that migrated from Rajasthan centuries ago. The Rabari women are known for producing gorgeous and impressive embroidery which is emblematic of their nomadic life. Rabari embroidery is a pictographic representation and symbolic of the mythology, rituals, culture, and life of Rabaris. The Rabaris are subdivided into groups which have distinguishing hand embroidery vocabulary of the composing the chain stitch, the back stitch, and herringbone. Mirrors of all shapes and sizes are liberally utilized. They use codis (beads) and thread fingers to edge the corners. The Rabaris produce native embroidery and garments on a massive scale. Given their nomadic nature, they also believe in ornamenting their cattle and homes. Amongst the Rabaris, men and women have a very different style of traditional wear. The subgroups of Rabaris are distinguished with subtle differences in their traditional attire, weaving and embroidery. Usually, Rabari women can be seen wearing a three-part ensemble consisting of a tubular woollen skirt or a pachhedo along with a backless blouse called kapadun. The men mostly wear a white cotton dhoti. Both the sexes wear jewellery made from silver metals and other ornaments which are mostly crafted by people from their own community.

Ramacham Root/ Vetiveria Carving of Kerala,

Ramacham root or Vetiveria (Vetiveria Zizaniodes) is a boon to the tropical heat of India renowned for its perfume, cooling and medicinal properties, is crafted into a number of products specifically designed to counter the hot humidity. Grown in India Ramacham founds many medicinal, cooling and incense properties. The roots are crafted into products like hats, fan, mats, blinds, and chappals/footwear etc as this material emits wiffs of a cooling perfume if periodically sprinkled with water during use. Ramacham infused water is also drunk due to widely prevalent belief that it lowers the body temperature in scorching heat. Ramacham blinds help to shade house from harsh sunlight, keeping rooms cool and roofs of the house are covered with dried ramacham and sprinkled with water to keep entire houses cool. Indigenous room coolers generate sprays of moist perfumed air with the aid of a motor and ramacham

Ramacham root or Vetiveria (Vetiveria Zizaniodes) is a boon to the tropical heat of India renowned for its perfume, cooling and medicinal properties, is crafted into a number of products specifically designed to counter the hot humidity. Grown in India Ramacham founds many medicinal, cooling and incense properties. The roots are crafted into products like hats, fan, mats, blinds, and chappals/footwear etc as this material emits wiffs of a cooling perfume if periodically sprinkled with water during use. Ramacham infused water is also drunk due to widely prevalent belief that it lowers the body temperature in scorching heat. Ramacham blinds help to shade house from harsh sunlight, keeping rooms cool and roofs of the house are covered with dried ramacham and sprinkled with water to keep entire houses cool. Indigenous room coolers generate sprays of moist perfumed air with the aid of a motor and ramacham

Rambaans/Natural Fibre Craft of Dehradun, Uttarakhand,

Rambaans is a type of the sisal plant, which grows in abundance in the lower hills of Uttarakhand. The plant has long fleshy blades as leaves which radiate from the roots. A process similar to the one used for extracting jute and hemp using the decorticator machine, is used to extract a glossy but stiff cream-coloured fibre. It is brought into use after having been processed and treated to make utility and decorative products. The fibre is brought into use to make toys, rope, tablemats, bags and hats among other things by either bunching, rolling or braiding it. This craft is practiced in the Dehradun district of Uttarakhand.

Rambaans is a type of the sisal plant, which grows in abundance in the lower hills of Uttarakhand. The plant has long fleshy blades as leaves which radiate from the roots. A process similar to the one used for extracting jute and hemp using the decorticator machine, is used to extract a glossy but stiff cream-coloured fibre. It is brought into use after having been processed and treated to make utility and decorative products. The fibre is brought into use to make toys, rope, tablemats, bags and hats among other things by either bunching, rolling or braiding it. This craft is practiced in the Dehradun district of Uttarakhand.

Rari Weaving – Woollen Rugs and Blankets,

The rari, a hardy woollen rug and blanket, has been used throughout Nepal for as long as people can remember. A long established source of income, it is based on the extraordinary skill of the Gurung weavers who very probably brought about the first recorded trade transactions from Nepal - namely, the export of woollen blankets to India in the third century AD. An essential part of every home, it is put to many uses, though its specific, ritually prescribed use is limited to periods of birth and mourning. It is an important part of the dowry. Rari weaving has its roots in antiquity and it is the best known of all woollen woven items. Its weaving is so common and widespread in Nepal that it is practised in most villages in the high and mid-hill regions.

The rari, a hardy woollen rug and blanket, has been used throughout Nepal for as long as people can remember. A long established source of income, it is based on the extraordinary skill of the Gurung weavers who very probably brought about the first recorded trade transactions from Nepal - namely, the export of woollen blankets to India in the third century AD. An essential part of every home, it is put to many uses, though its specific, ritually prescribed use is limited to periods of birth and mourning. It is an important part of the dowry. Rari weaving has its roots in antiquity and it is the best known of all woollen woven items. Its weaving is so common and widespread in Nepal that it is practised in most villages in the high and mid-hill regions.

TRADITIONS

Though woven all over Nepal, the rari has been associated with the Gurungs for centuries. It is believed that the finest quality rari is made in Rumjatar in east Nepal, where it is a cottage industry. Used to sit or sleep on or as a rug, the small, fringed sleeping-mat (burkasan) is about 70 cm X 150 cm in size; larger raris are made up from two or more panels joined at the selvedge.

Traditionally, it is the women who prepare the yarn and weave the rari in their leisure hours, when their agricultural and household duties are done; the men do the final finishing and felting, or help with the warping or the heavy wool embroidery which is applied after weaving. It is the man's job to sell raris that are woven for sale - it is a common sight to see men carrying three or four raris of different sizes on their shoulders at markets and village bazaars while they look for buyers. The rari is priced much lower than the Tibetan woollen carpets and there is a huge demand for them in the winter months. The weaving is therefore timed for the summer and the selling in the chilly months of winter.

The rari not only serves the purpose of pallet but is also used for a number of other purposes. A high quality rari can be converted into a warm overcoat (bakkhu) or into warm vests, scarves, and bags. Rari weavers have made modifications in sizes and patterns to capture changing requirements and are also weaving small-sized pieces with coloured designs on them. The traditional rari, however, is still a valuable trade item even today at village markets as well as in the streets of Kathmandu.

RAW MATERIALS

The local baruwarl sheep is the main and most sought after source of raw material for rari weaving, though other varieties of local wool are also used. The fleece of the baruwarl is short and rather hard. Garments are woven mainly from the soft wool of the first and second shearing, and raris from later shearing. The different shades of the baruwal fleece - ranging from white, to beige and brown, and black - are used by the weavers in patterning. Tapestry-type patterned blankets are also sometimes dyed with ochre, obtained from walnut shell, and light red from madder.

The main varieties of baruwala wool include:

- Garve wool - that is obtained from a lamb whose wool has never been sheared - this wool is obtained as a first crop and is therefore very soft, fine, and of high quality.

- Chharve wool - a variety that is obtained as a second or third crop of the baruwala and is less soft and of medium quality.

- Torbe wool - the third variety of the baruwala is obtained as a third or forth crop. It is usually rough and of low quality.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

The wool is carefully sheared using a chupi (knife); as a large quantity of wool is required the rari maker often needs to go to other villages to fulfil the requirement of wool. The quality of wool thus collected is therefore of different grades.

The wool is then washed, dried, matted, and heaped together in a big entangled mass. It is then shredded into soft fluffy fur. This is done with a special instrument that is shaped like a large wooden bow linked with a fine skin rope (dhanu). The people of the Terai are experts in its usage and they travel from village to village with their triangular dhanu on their shoulder. The dhanu carrier is an expert - in a short time he can break up two or three dharnis of lumpy cotton or wool into fluff. He hits the string of the skin rope with a wooden handle, and the vibrating string continuously hits the lump of wool or cotton, breaking it apart instantly.

The spinning wheel or charkha made of wood is used in preparing yarn out of raw wool or cotton by rotating the spindle; it is then wound on the pin of the wheel.

The yarn (tan) is then stretched in parallel positions on the loom on which the actual weaving is done. The main components of the loom are similar across the board, but some Gurung weavers in east Nepal use cross-sticks rather than the coil-rod warp separator, and the warp is laid without the warp lock-stick.

When the weaving is complete, it is taken off the loom; the un-woven warp threads (12-20 cm long) at the end or between the panels are looped around each other to form a secure border with warp fringes when the circular warp is cut. The cloth panels are then ready for finishing, joining, or tailoring; however, there is still some work to be done on the raris before they undergo their more unusual finishing/felting process. The burkasans used for sleeping, are usually woven full width and need no joining; where they have fringes all the way round, these are added at this stage. Woollen, two-ply yarn strands (15-20 cm long) are knotted into both the selvage sides with lark's head knots. Larger raris are joined at the selvage to form a complete pattern. Before the stitching a lot of pulling and stretching often has to be done so that the pattern will actually meet.

For the highly valued double blanket/rug, two single raris of the same size but with different patterns are placed one on top of the other and joined by knotting the fringes through both layers of selvages. The two blankets will adhere completely during the felting process, giving the impression of a single piece of weaving and concealing how this rug with two completely different sides was woven.

The quality of the rari, including its ability to withstand wind and water, depends, to some extent, on the finishing/ felting process, which might take a whole day. The rari is then dipped in lukewarm or cold water and rubbed vigorously on a large flat stone slab or wooden plank, preferably by trampling. The more the rari is rubbed, the thicker it becomes - as the stamping operation is tedious and difficult, it is usually done by the men. This process is repeated three times. The felter, supported by two long bamboo sticks, shifts his weight from one foot to the other during this process of felting. This causes the thin net-like structure of the rari to disappear, giving the product a uniform smoothness and thickness. Raris shrink considerably during felting and through the matting of the yarn fibres the texture becomes so close that sometimes one cannot recognise it as weaving.

Raw Material, Textiles, Technology in Punjab,

Textile industry is the worst offenders of all when it comes to environment safety and pollution control. All the processes of the textile and apparel industry require use of water in sizing, desizing, and scouring, bleaching, mercerization, dyeing, printing, finishing and ultimately washing. All the processes using large amount of chemicals hazardous in nature and a definite discharge of harmful waste water that goes into the fresh water rivers and streams. Thus effluent treatment is an immediate preventive plan to avoid any more damage to the ecosystem and water bodies. Effluents treatment plants are considered to be widely accepted approaches towards achieving environmental safety. On close observation of the kinds of pollutants are generated, no single treatment methodology is suitable or universally adoptable for any kind of effluent treatment. The biological treatment systems used extensively were not efficient for the colour removal of the more resistant dyes. Only after studying the needs and levels of treatment required, it is decided to what kind of treatment plan should be followed. The treatment processes may be categorized into preliminary, primary, secondary and tertiary treatment process.

Textile industry is the worst offenders of all when it comes to environment safety and pollution control. All the processes of the textile and apparel industry require use of water in sizing, desizing, and scouring, bleaching, mercerization, dyeing, printing, finishing and ultimately washing. All the processes using large amount of chemicals hazardous in nature and a definite discharge of harmful waste water that goes into the fresh water rivers and streams. Thus effluent treatment is an immediate preventive plan to avoid any more damage to the ecosystem and water bodies. Effluents treatment plants are considered to be widely accepted approaches towards achieving environmental safety. On close observation of the kinds of pollutants are generated, no single treatment methodology is suitable or universally adoptable for any kind of effluent treatment. The biological treatment systems used extensively were not efficient for the colour removal of the more resistant dyes. Only after studying the needs and levels of treatment required, it is decided to what kind of treatment plan should be followed. The treatment processes may be categorized into preliminary, primary, secondary and tertiary treatment process.

Razai/Quilt Making of Jaipur, Rajasthan,

Jaipur is known for its lightweight, warm and durable quilts. Quilt making is a long process and completed after many stages of processing. The process starts with the bales of cotton that are brought by the quilt maker from cotton dealers; which is then carded into a fluffy mass with all dross and waste products removed. The art of carding can change the quality of quilt produced. The quality does not lie on the type of cotton but the amount and quality of carding that is done on bales. A one 1 kilogram of cotton is carded into 100 grams after a full week of carding. The lightest of quilts do not weigh more than 50 grams. The origin of the Jaipur quilt goes back 250 years when the ruler Sawai Jai Singh II brought many quilt makers, mansuris from around and near Amber city to Jaipur and settled them down there. Quilt making is a popular crfat practised in Rajasthan. The thin Jaipuri razai is well known across several regions. Production clusters are centered around Japiur's Topkhana ka rasta and Chandpole bazaar. Products such as razai(quilts), gadda(quilted cushions) and quilted bedsheets are created under this craft-form. Tools such as rulers, cardboard cutouts for floral motifs, stick used for separating the separated cotton fibres, beating tool, and needles are employed for the process. Production clusters are centered around Japiur's Topkhana ka rasta and Chandpole bazaar. Products such as razai(quilts), gadda(quilted cushions) and quilted bedsheets are created under this craft-form. Tools such as rulers, cardboard cutouts for floral motifs, stick used for separating the separated cotton fibres, beating tool, and needles are employed for the process.

Jaipur is known for its lightweight, warm and durable quilts. Quilt making is a long process and completed after many stages of processing. The process starts with the bales of cotton that are brought by the quilt maker from cotton dealers; which is then carded into a fluffy mass with all dross and waste products removed. The art of carding can change the quality of quilt produced. The quality does not lie on the type of cotton but the amount and quality of carding that is done on bales. A one 1 kilogram of cotton is carded into 100 grams after a full week of carding. The lightest of quilts do not weigh more than 50 grams. The origin of the Jaipur quilt goes back 250 years when the ruler Sawai Jai Singh II brought many quilt makers, mansuris from around and near Amber city to Jaipur and settled them down there. Quilt making is a popular crfat practised in Rajasthan. The thin Jaipuri razai is well known across several regions. Production clusters are centered around Japiur's Topkhana ka rasta and Chandpole bazaar. Products such as razai(quilts), gadda(quilted cushions) and quilted bedsheets are created under this craft-form. Tools such as rulers, cardboard cutouts for floral motifs, stick used for separating the separated cotton fibres, beating tool, and needles are employed for the process. Production clusters are centered around Japiur's Topkhana ka rasta and Chandpole bazaar. Products such as razai(quilts), gadda(quilted cushions) and quilted bedsheets are created under this craft-form. Tools such as rulers, cardboard cutouts for floral motifs, stick used for separating the separated cotton fibres, beating tool, and needles are employed for the process.

Recycled Crafts,

The methods and processes of handicrafts are so well established and rehearsed that nothing is ever wasted. Materials in the subcontinent are cycled and recycled - by fashioning new products to suit needs and tastes with left over or old materials. 'Waste' in the form of paper, rags, straw and palm are all transformed into objects of utility and decoration. Examples of these are the transformation of torn and tattered sari into coiled and plaited rugs and wall-hangings, empty glass bottles into vases or a pen-holders, geometric and floral decorations made from empty cigarette packets, egg-shell converted into birds and dolls, painted pebbles, rag dolls, sculptural figures made with pistachio and pea-nut shells.

The methods and processes of handicrafts are so well established and rehearsed that nothing is ever wasted. Materials in the subcontinent are cycled and recycled - by fashioning new products to suit needs and tastes with left over or old materials. 'Waste' in the form of paper, rags, straw and palm are all transformed into objects of utility and decoration. Examples of these are the transformation of torn and tattered sari into coiled and plaited rugs and wall-hangings, empty glass bottles into vases or a pen-holders, geometric and floral decorations made from empty cigarette packets, egg-shell converted into birds and dolls, painted pebbles, rag dolls, sculptural figures made with pistachio and pea-nut shells.

Reed Mats of Tamil Nadu,

A reed is a firm-stemmed grass, with a hollow stem that looks like bamboo. It is a sturdy material and reed mats are used as walls for structures and roofs. The reed is first split and shaved before it is woven in a twill weave into mats. They are made starting at one corner and plaiting or weaving is done diagonally. Long strips are folded at the middle and another strip is inserted crosswise, which is in turn folded and the next strip is again inserted crosswise and so on. The creases of the crosswise strips form the edges of the mat. Reeds are also used to make very sturdy baskets.

A reed is a firm-stemmed grass, with a hollow stem that looks like bamboo. It is a sturdy material and reed mats are used as walls for structures and roofs. The reed is first split and shaved before it is woven in a twill weave into mats. They are made starting at one corner and plaiting or weaving is done diagonally. Long strips are folded at the middle and another strip is inserted crosswise, which is in turn folded and the next strip is again inserted crosswise and so on. The creases of the crosswise strips form the edges of the mat. Reeds are also used to make very sturdy baskets.

Repousse Metal Craft of Uttar Pradesh,

Repousse is done on all types of articles. The objects are first moulded into the required shape and burnished; the engraver then traces the design with a chisel, filling up the open ground with dots and spots produced by punching. The work is very light, often little more than an outline drawing. Formerly much more skill was displayed by the Benares engravers, and the decay of their art may be attributed partly to the influence of western ideas. The metal repousse process is entirely done by hand, using the traditional tool. It is a home-based activity, one in which the artisans have been working since generations.

Repousse is done on all types of articles. The objects are first moulded into the required shape and burnished; the engraver then traces the design with a chisel, filling up the open ground with dots and spots produced by punching. The work is very light, often little more than an outline drawing. Formerly much more skill was displayed by the Benares engravers, and the decay of their art may be attributed partly to the influence of western ideas. The metal repousse process is entirely done by hand, using the traditional tool. It is a home-based activity, one in which the artisans have been working since generations.

Rezkar embroidery of Kashmir,

Very similar to sozni technique, Rezkar embroidery constitutes of longer stitches and there is no reinforcement of these stitches with additional ones. Textiles such as shawls, garments, table covers, bedspreads household linen and capes are produced using this technique.

Very similar to sozni technique, Rezkar embroidery constitutes of longer stitches and there is no reinforcement of these stitches with additional ones. Textiles such as shawls, garments, table covers, bedspreads household linen and capes are produced using this technique.

Ringaal Basketry of Almora, Uttarakhand,

During winters when the fields are being sowed and the farmers don't have much work to do they take up the craft of basketry. The baskets are prepared with a special type of bamboo which is locally known as Ringaal. Ringaal is a smaller species of bamboo grass growing up to 3 to 5 meters only. The length is also affected by the altitude; a grass grown at 3000 to 5000 feet is serviceable for basketry. The stalk of the grass made flat and the outer skin is used as splits to interlace into basket. Firstly the warp split is beaten to become flat which is then intertwined in a twill weave and extra weft interlacing at the bottom and rim to provide strength and support. The extra weft twining is locally known as tyal weaving. The mat made through ringaal bamboo is made with a basket weave and winnows are made in close weave with twill pattern. The flooring of many traditional houses in Kumaon and Garhwal region is done with ringaal mat pasted on mud base flooring.

During winters when the fields are being sowed and the farmers don't have much work to do they take up the craft of basketry. The baskets are prepared with a special type of bamboo which is locally known as Ringaal. Ringaal is a smaller species of bamboo grass growing up to 3 to 5 meters only. The length is also affected by the altitude; a grass grown at 3000 to 5000 feet is serviceable for basketry. The stalk of the grass made flat and the outer skin is used as splits to interlace into basket. Firstly the warp split is beaten to become flat which is then intertwined in a twill weave and extra weft interlacing at the bottom and rim to provide strength and support. The extra weft twining is locally known as tyal weaving. The mat made through ringaal bamboo is made with a basket weave and winnows are made in close weave with twill pattern. The flooring of many traditional houses in Kumaon and Garhwal region is done with ringaal mat pasted on mud base flooring.

Ritual Cloth Installations of Ladakh,

There are a variety of products produced under this craft form like Dhukh-canopy, Kaphen-pillar hanging, Shambhu- pleated door hanging, Lungsta- prayer flag,and chubar- cylindrical hanging.

There are a variety of products produced under this craft form like Dhukh-canopy, Kaphen-pillar hanging, Shambhu- pleated door hanging, Lungsta- prayer flag,and chubar- cylindrical hanging.

Ritual Masks of Papier Mache,

Brightly painted ritual masks worn during religious ceremonies and processions in Nepal are made of perishable materials such as papier mache and wood, plastered with clay and linen. The art of making these masks is alive and alive and vibrant; age-old tradition dictates the use of new masks for religious processions and ceremonies and the ritual destruction of masks that have already been put to use. Masks have played an important role in the observation of social and religious traditions in Nepal - and the part they play is both symbolic and self-explanatory to the worshipper and the spectator. In Nepal, masks are used almost exclusively in religious processions and functions; unlike in other parts of the world they are not used as part of theatrical and commercial performances. In the last few decades the crafting of these ritual masks has received a huge boost and their marketing has been greatly commercialised due to the interest evinced in them by the tourists and the export market.

Brightly painted ritual masks worn during religious ceremonies and processions in Nepal are made of perishable materials such as papier mache and wood, plastered with clay and linen. The art of making these masks is alive and alive and vibrant; age-old tradition dictates the use of new masks for religious processions and ceremonies and the ritual destruction of masks that have already been put to use. Masks have played an important role in the observation of social and religious traditions in Nepal - and the part they play is both symbolic and self-explanatory to the worshipper and the spectator. In Nepal, masks are used almost exclusively in religious processions and functions; unlike in other parts of the world they are not used as part of theatrical and commercial performances. In the last few decades the crafting of these ritual masks has received a huge boost and their marketing has been greatly commercialised due to the interest evinced in them by the tourists and the export market.

TRADITIONS & CLASSIFICATIONS

Broadly speaking, the masks representing gods, goddesses, demons, and animals can be classified into four main categories.

- Masks that represent gods and are worn by humans.

- Ornamental masks that are used in temples in observance of religious rituals.

- Masks that are used in processions while celebrating festivals and jatras.

- Masks that are made especially for the tourist trade.

The first three categories adhere to strict rules of iconography and iconometry. These masks - representing gods, goddesses, and demons are endowed with their own attributes and are cast according to the ritual or scene that is to be worshipped or depicted, thereby resulting in immediate identification by the worshipper. As these masks represent images of deities that are worshipped, they need to be constructed very carefully - even the colours used carry their own message(s) and significance. For instance, red is associated with animal sacrifices and anger, blue-black with energy and power, and white with purity and death. The mask is only one part of the ensemble; the dancers must also wear the appropriate clothes and ornaments, which, along with the mount, motifs, the mukuta (crown), and accessories, are also represented with their exact attributes. Masks are not only distinguished from each other by their forms and by their colours but also by their very distinctive and individual head-gears.

Besides representing gods, goddesses and demons the masks also include representation of tigers, bears, lions and other animals. And all the dancers who wear masks are men The processions on the occasion of the major festivals are important parts of the proceedings.

The dances of the nava-durga in all localities of the Kathmandu Valley are linked with the agricultural cycle, and in particular with rice production. The masked dances cease during the monsoon. The masks used in Bhaktapur and at Kathmandu are ritually destroyed with fire before the monsoon starts; they 'come to life' or are re-made in the month of September, during the festival of Dussehra. The exception to this rule are the masks of the nava-durga dancers at Theco, formerly a part of the kingdom of Patan: these are not destroyed annually after the troupe's performance, but are instead repaired, re-plastered, and re-painted every year and stored in the temple. Every 12 years, however, at the time of the major festival of Theco, new masks are made and the old masks; the old masks are not destroyed but now stored in the attic of the local temple.

PRACTITIONERS & CRAFT LOCATIONS

The masks made traditionally as well as in contemporary times, are made by members of the Newar chitrakar community of painter. The painters follow the rules of iconography very carefully or else the masks cannot be consecrated, and subsequently cannot be used for religious purposes. The chitrakars pass through a religious initiation (diksha) before they can employ their training in the making of ritual masks.

Thimu and Bhaktapur are the main centres for crafting masks that are used in ritual masked dances and processions.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

For religious and ritual masks, strict rules of iconography have to be adhered to. For each deity, the exact proportions, colours, symbols, and mukuta (crown/diadem) are laid down. Reference folding books - containing details of the dimensions, colours, and attributes for the images of the different gods and goddesses - are available to chitrakars, and are followed scrupulously. It is believed that if the rules of iconography are not followed a benevolent deity can become a demoniac force; therefore a painter cannot break any rules while depicting a religious image. A in existence a number of folding books of iconographic drawings are still available, the earliest one dating from the first half of the fifteenth century.

As these masks are ritually destroyed after use - and thus need to be continuously renewed and remade - tradition dictates that the new masks contain a bit of the old as well. Therefore, in the months of April and May, on the day of sithinaka, when ponds and wells throughout the Kathmandu Valley are cleansed, the old masks are burnt; and most of the ashes are cremated, some proportion is used in the new masks, thereby creating a link with the past - a sense of continuity. The ritual mask painting is done in the month of August/September, one month before the Dussehra festival.

The masks are made of clay mixed with bits of cotton and a locally made gum paste made from wheat flour. This mixture is prepared by the painter and then separated into 13 parts. Each part is placed over a low-relief mould which is covered with a clean black cloth - the painters presses the flattened clay with his fingers so that it takes on the contours of the mould. The clay mask forms are left to dry on the moulds for about four days. After they are removed from the moulds, the masks are painted with a mixture of boiled wheat-flour, water, and animal glue; this dries to a semi-opaque finish. Previously, the chitrakars used vegetable and mineral colours to paint the mask; now, however, it is chemical colours that are predominantly used.

A CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVE

In the past two decades, many commercial artists in the Kathmandu Valley have started making masks for the tourist and export trade. Stores all over the Valley sell these masks, either as wall hangings or as puppets. Though not as beautiful and carefully constructed as the ritual masks, the masks made for commercial purposes are well-appreciated and have markets all over the world. The masks are sold in shops in Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur.

Rod Puppetry of West Bengal,

West Bengal has a rich tradition of rod puppetry, which is locally famous as putul nach (dancing dolls). The Bengali puppeteers believe that rods are stronger as compared to strings and lend greater support and freedom in giving the required animation as well as manipulation. Only a handful of people practice this art form in the rural areas of West Bengal now. The puppets are one and a half meter tall and are built over bamboo which may be two and a half meters long. The puppet has a basic bamboo structure over which a paste of hay and rice husk is plastered to give the required shape. The absence of legs is camouflaged with saris or dhotis draped over the puppets befitting the requirement of the character. Strings are attached to the elbows which allow for easy manipulation and displaying highly dramatic movements. The rod holding the puppet is placed in a bamboo socket which is firmly tied to the puppeteer's waist in front. The puppeteer's each holding a puppet; perform from behind a bamboo-curtain. While manipulating the puppets the movements of the puppeteer's appear to resemble dancing. The themes are inspired by Ramayana, Satee Behula.

West Bengal has a rich tradition of rod puppetry, which is locally famous as putul nach (dancing dolls). The Bengali puppeteers believe that rods are stronger as compared to strings and lend greater support and freedom in giving the required animation as well as manipulation. Only a handful of people practice this art form in the rural areas of West Bengal now. The puppets are one and a half meter tall and are built over bamboo which may be two and a half meters long. The puppet has a basic bamboo structure over which a paste of hay and rice husk is plastered to give the required shape. The absence of legs is camouflaged with saris or dhotis draped over the puppets befitting the requirement of the character. Strings are attached to the elbows which allow for easy manipulation and displaying highly dramatic movements. The rod holding the puppet is placed in a bamboo socket which is firmly tied to the puppeteer's waist in front. The puppeteer's each holding a puppet; perform from behind a bamboo-curtain. While manipulating the puppets the movements of the puppeteer's appear to resemble dancing. The themes are inspired by Ramayana, Satee Behula.

Rogan/Oil Painting on Fabric of Gujarat,

The history of roghan painting on fabric is centuries old. Roghan designs on cloth - with their embossed and shiny look - seem very similar to embroidery. The oil used for obtaining the pigment used in the painting is extracted from the seeds of the wild safflower: this is boiled for hours so that it becomes thick and oleaginous and is then coloured with pigments. The roghan or wax-like pigment so obtained is stretched onto the fabric by hand. It is then moistened with the fingertip and pressed onto the fabric. A special kind of dexterity is required to manipulate the roghan pigment threads on the cloth so as to obtain the required design. This craft is practised by only a few artisans in Nirona, a small village in Kutch (Gujarat). The craft was earlier practised in Ahmedabad and Pattan, also in Gujarat, and in Nasik (Maharashtra). Roghan painted cloth was earlier referred to as Afridi Lac cloth. The designs found are geometric and floral with motifs of birds and beasts. Saris, furnishing and dress materials, book covers, and a whole host of other items are being embellished with roghan. Due to lack of support, the craft is not being taught to the next generation and so it is dying out.

The history of roghan painting on fabric is centuries old. Roghan designs on cloth - with their embossed and shiny look - seem very similar to embroidery. The oil used for obtaining the pigment used in the painting is extracted from the seeds of the wild safflower: this is boiled for hours so that it becomes thick and oleaginous and is then coloured with pigments. The roghan or wax-like pigment so obtained is stretched onto the fabric by hand. It is then moistened with the fingertip and pressed onto the fabric. A special kind of dexterity is required to manipulate the roghan pigment threads on the cloth so as to obtain the required design. This craft is practised by only a few artisans in Nirona, a small village in Kutch (Gujarat). The craft was earlier practised in Ahmedabad and Pattan, also in Gujarat, and in Nasik (Maharashtra). Roghan painted cloth was earlier referred to as Afridi Lac cloth. The designs found are geometric and floral with motifs of birds and beasts. Saris, furnishing and dress materials, book covers, and a whole host of other items are being embellished with roghan. Due to lack of support, the craft is not being taught to the next generation and so it is dying out.

Tradition and History

The art of roghan painting on cloth goes back centuries. Local legend has it that this art came into India from the Afridis, originating in Syria; the route it followed wound through Persia, Afghanistan and Pakistan, and then to India. The craft became concentrated in the northwestern parts of India, and was practised mainly by the Muslim descendants of the Afridis - the product came to be called Afridi lac cloth or Peshawar lac cloth. Sir George Watt in his book Indian Art at Delhi, an exhibition catalogue published in 1903, found that a similar craft form was practised not only by the Afridis but also in Peshawar, Lahore and Pattan where castor oil was used and in Kutch where linseed oil was the base. In all these centres the craft was practised by Muslims possibly descended from the Pattans.

George Watt also described the 'Afridi wax print' process and how the oils were extracted using both the hot and cold methods. It is noted that wild safflower or poli seeds were crushed to extract the oil and boiled for 12 hours after which they were plunged in water; as a result of this, this became a gelatinous substance called roghan. In the Kutch region of Gujarat, he noted that castor seed or khardi seeds were used for the oil-extraction and that this process was difficult as the results depended on a high level of skill and dexterity.

To quote from T.N. Mukharji's Art Manufactures of India, published in 1888 for the Glasgow International Exhibition: 'Another curious variety, which, though not cotton-printing strictly speaking, may be conveniently noted here, is the lac and colour painting on red and blue cotton fabrics produced in the Peshawar District. Blocks are not used, but red, yellow and other colours in a thick sticky pigment are applied in bold semi-barbaric patterns, on which, as they dry, abrak or powdered talc is sprinkled.' He further notes that roghan was extracted from linseed oil and that the craft was not confined only to the Panjab frontier, but was also being practised by Hindus at Ahmedabad and Morvi, in the Bombay Presidency. At Nasik, similar kinds of processes were noticed - the use of a perforated stamp fixed at the end of a tube full of colour used to produce a pattern similar to the perforated cylinders used to make patterns in front of thresholds. The colour used was either in the form of a dry powder or mixed with linseed oil. When the paint dried on the cloth, dried mica was sprinkled over it. At Peshawar it was noted that the technique followed was a little different: the work was traced with a stick, there was no use of stamps or cylinders, and the quality of the colours used was very good.

Feliccia Yacopino has stated in her book, Threadlines Pakistan, that Afridi wax cloth was sold in the bazaars of Peshawar, Lahore and Karachi where it was known as 'khosi', from the word 'khosai' (the dress of the Afridi women).

The colours used for roghan included trisulphide of arsenic for yellow, red lead oxide for red, white lead or barium sulphate for white, and indigo for blue. Powdered lime was added to thicken the runny roghan into a workable consistency and mica flakes - along with gold and silver leaf - were also pressed into the raised patterns for tinsel work. It has been recorded in George Watt's book that the artisan makes the roghan paste into a small ball in the heel of his left palm with a six-inch metal rod. The stylus or the instrument used to transfer the designs onto the cloth is held in the right hand into which the Roghan is put; from this the coloured material flows according to the pattern being made by the artisan. Finger art roghan designs even than were done by free hand.

Even though, traditionally, roghan-designed cloth was used both in India and abroad for clothing and furnishings - as table cloths, household decorations, prayer cloths and fire screens - yet roghan was only a marginal tradition and not very well known.

Practitioners and Location

There are now only a few artisans in Nirona (Kutch) practising the art of roghan painting. These artisans have been practising this craft for generations. There are a few other families from Chobari village (also in Kutch) who also practice this craft. We spoke to Khatri Sadiq Bhai whose family has been practising roghan for eight generations. There are about four other artisans from his village who still practise this craft; however, when more lucrative opportunities are available, they are willing to abandon the craft. Khatri Sadiq Bhai himself left roghan painting for six years to set up a textile shop, but returned to practise his family's traditional craft form again.

Materials, Processes and Techniques

The basic raw material used to make the roghan are the seeds of the wild safflower (carthamus oxyc anthus), and linseed or castor seeds which are pressed to produce oil. The seeds are all hand-pounded and then boiled for over 12 hours to thicken the substance: it is then thrown into cold water to get the roghan. The water in which the roghan is immersed prevents it from drying out. The roghan is then coloured with various dyes: red, white, yellow, blue and green are popular colours, while silver and gold leaf is used to create special effects. The roghan is made into a workable consistency by adding a quantity of lime to it. The practices followed and the materials used for the roghan painting have not changed over time, proof of which can be found from notes on the craft from almost a hundred years ago.

The chief tool used in roghan painting it is a six-inch metal stylus that has a pointed tip. The artisan places, by rough measure, about a teaspoon of roghan on his left palm; the roghan is then made pliable and of a workable consistency by using the palm as a palette and by briskly mixing it with the stylus. The stylus is then used to stretch and draw out the roghan threads on to the fabric to form the desired design through free-hand application or by following the lines of a pre-drawn design. Artisans with a high level of skill and dexterity work very comfortably from left to right as well as from right to left.

Interestingly, when the design being is painted, the stylus does not touch the surface of the cloth; the transfer of the semi-solid roghan thread is done with great deftness and skill. The cloth is held by the artisan from underneath and is moved forwards and backwards according to the needs of the pattern being laid out. With years of practice, this process can be made to appear very effortless. When the design made is intended to be identical on the two halves of the cloth, the design is painted onto one side of the cloth and the cloth is then folded onto itself: the design transfers itself in a mirror image on the other half.

When a solid patch of colour is required, the artisan allows the stylus with the dangling thread of roghan to move over the area in a single direction. So parallel lines of roghan are laid down next to one another and the threads are pressed down with a moistened fingertip: the threads thus adhere to one another and form a coloured patch. Colours are applied one by one and only when one colour has been used exhaustively is the next colour introduced. When Khatri Sadiq Bhai of Nirona demonstrated roghan painting, the effortless ease with which the design unfolded and took shape was a marvellous indication of the skill involved.

When the roghan thread has been placed on the fabric with the stylus, the artisan presses it into the fabric with a moistened fingertip. The roghan sinks into the fabric of the material and adheres to it. When the roghan dries, it is hard, and the fabric can then be washed without any problem. Powdered mica or abrak and imitation gold powder can be added onto the roghan design to give the whole design a silver or golden sheen. Even after the roghan dries, the sheen and gloss remain: the powder does not rub off. Fabric with roghan on it is very durable and can be washed with no loss in its sheen or pattern.

Design and Products

The designs found in roghan usually include geometric and floral patterns, with birds and beasts being depicted sometimes. The products made include saris, cushions, kurtas (long dress-like shirts), home furnishings, ghagras (long skirts), wall hangings, book covers, file covers, table linen and bed covers. Earlier there was a demand for roghan embellished products like chabla, dhranjo and other items of clothing; this demand has, however, given way to a demand for the items mentioned above.This unique but fading craft has a lot to teach us. Its use of different oil seeds in creating colour for textile embellishment is of value to all serious researchers, students and designers. The need of the hour is to create new products and markets for this craft, which undoubtedly has the possibility of increased growth and development.