Kuthuvilakkus (lamps) usually consist of four parts:base (“keezh-bagam”), stem (“kandam”), oil container (“thanguli”) and the apex (“prabai”). The “thaguli” or oil container consists of V-shaped spouts to hold the wicks. These four parts are joined together with the help of screw threads. Lamps are also made in the shape of a branching tree, each branch ends with a small tray or bowl for the oil and wick. Kuthuvilakkus are manufactured in various sizes and also in the form of a standing woman holding in her hands a shallow bowl to contain the oil and the wick. They are used on religious and ceremonial occasions and are fashioned out of brass. The manufacture of bell-metal wares has always been the traditional occupation of the Pather community. However, in recent years, raw materials are difficult to procure; tin, for example, has become costly and scarce. As a result, many of the members of the Pather community have abandoned their craft.

The characteristics of the Nagpur sari are the designs that are woven with the Nagpuri wooden dobby in extra warp. The sari is woven on a pit-loom and the raw material used is pure cotton yarn. Designs have their own names and are woven in stripes and checks with fly shuttles, contrasting the finely textured body with richly patterned borders.

An unusual form of embossed illustration that has been practised in India is nail embossing. In this craft form, the artist uses his nail as a tool rather than a paint brush. The nail when dug into the paper creates an embossed effect and many designs and patterns are created in this way. Flowers, animals, human figures, scenery and other subjects are all embossed in this manner. The designs created are either presented as a tone on tone embossed effect or they are coloured in to add greater variety for the purchaser. T. N. Mukherjee in his book Art Manufactures of India that was compiled for the Glasgow International exhibition of 1888 writes that "in many parts of Upper India an ornamental scroll work is made on paper by the finger nail which has been rightly characterized by Mr. Kipling as of the numerous examples of futile ingenuity for which India is remarkable". He then goes on to state that embossed nail work was sent from Indore for the Calcutta International Exhibition.

A fine example of folk art and the individual creative impulse is the Nakshi Chhanch - moulds made for rice cakes – the nakshi pithas. The village women of Bangladesh apply their creative impulse and talent to decorate the rice cakes made to celebrate the harvest. Drawing not only upon their imagination but on their daily experiences the women create the nakshi chhanch. Traditionally made of either clay, wood or stone the moulds are crafted in different shapes and sizes, each with different patterns and designs. Rice flour ground very fine in a dhenki is the main ingredient of the cake/pitha that is offered to visitors and members of the family to celebrate the harvest and the Bengali New Year. Flour is kneaded with water into a variety of shapes. Sometimes the juice of taal / date palm, gur /molasses, milk, coconut, ginger, sugar or spices are also mixed in. There is an endless variety of pithas and each one has a specific name. The more interesting versions are the bhapa (steamed) pitha, chitoi, pakwan pitha and malu pitha. Some of these are like plain pithas; steamed or fried. But in the nakshi pitha, the design is very important and the ingenuity expressed in designing the moulds in shapes that range from birds, dolls, fruits, conch shell, leaves and animals among others add value to the offering.. This folk craft is practiced mainly in Mymensingh, Comilla, Sylhet, Dhaka and Chittagong.

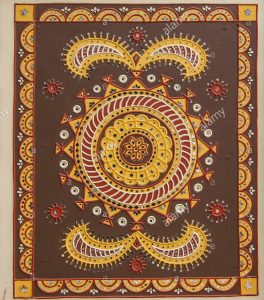

The legendary nakshi kanthas are the best examples of the embroideries of Bangladesh. Although embroidered kanthas are very decorative their chief motive traditionally was thrift and economy combined with aesthetics, the idea being to utilise old and worn out cloth by sewing them together meticulously with close stitches and embroidering them so that not a single piece of fabric was wasted. The idea was to strengthen old and worn out cloth so that it could endure further usage. The care and artistry with which the embroideries are made transformed the kanthas from their original state of patched up rags into wonderfully beautiful creations of design. Nothing embodies the tradition of women’s creativity more than the nakshi kanthas. It also symbolizes how women preserve, recreate and renew life forms. Stories are told of how women met together in their courtyards, to stitch the kanthas for family members. They stitched the layers together with borders in coloured yarn taken from the sari borders; this was followed by stitching the motifs which represented familiar items, ritualistic symbols or imaginative scenes. It is said that almost fifty different stitches have been used in kanthas.

Embroideries have always been considered as a highly personalised form of expression influenced by culture, traditions and the local surroundings. Moreover, the tradition of patching and quilting textiles in the Indian subcontinent has a long history.

The Kantha stitch and the subsequent profession of embroidery became a common income generating option which could be pursued from home by women across several parts of the country.

Nakshi Kantha is a folk form of quilting old dhotis, sarees and other old clothes and embroidering them with coloured threads drawn from saree borders. The embroidered patterns depict elaborate and intricate floral, animal, human and other household motifs along with social and cultural scenes from Bengal in the 19 century. Kanthas serve primarily as bed pallets and as light wraps. Small kanthas are used as swaddling clothes for babies, depending on their size and use. Kantha embroidery uses the “dorukha” or double-faced character stitch. The embroidery appears on both faces of the kantha. The stitches are so skilfully applied that the details of each design appear in identical forms and colours on both sides, making it extremely difficult to distinguish the right face from the reverse

The making of the embroidered fan or Nakshi Pankha is as popular a traditional art as the Nakshi Kantha. Commonly used by the village folk as a hand fan, it is very attractive in design, pattern and colour combination. A product of artistic skill and ingenuity, embroidered fans reflect the aesthetic sensibility of the makers, as various floral, bird and geometrical motifs are cleverly sewed through. Embroidered hand fans are made of various material including cloth, bamboo, palm leaf, straw and mat. Individual names have been attributed to the fans, such as, Bhalovasa (love), Amay bhulana (don’t forget me), Tara phul (star motif), Sankhalata (conch shell pattern), often the central motif is a tall stylised tree with branches on which several parrots are seated, balanced on the two sides typical with elephants, facing each other, interspersed with leaves and geometric patterns.

Decorative, colorful strings, knotted together into a woman's braid or designed into hair buns, parandas form an important part of women' attires in Punjab. The tassels are highly decorative: red is usually used for brides, gold or silver for special occasions, and other colors to match the everyday apparel. The Nala is the drawstring that holds up the lower garment at the waist be it a salwaar, pajama/women and men’s loose pant or the ghaghra gathered skirt. They are elastic across their width and the net-like surface is patterned with motifs.

The Patiala nala and paranda were famous as they were more elaborate and made of fine resham, silk, with decorative tassels that hung low and could be seen from under the kameez, upper garment.

Before the advent of factory made nala and paranda this was a household craft with every woman twined, plaited and knitted her own and these skills were passed on from mother to daughter. While techniques varied the nala were usually made by using the sprang technique where a net-like structure was formed by twisting and twining the wrap elements. Twists made at the top automatically formed at the bottom till the rows meet. The ends were then knotted into either a round or square knot called the harad after the black myrobalam as it resembled the fruit and then were plaited from the knot into naliyan or fine braids.

Using simple basic tools of the adda/frame and karma -sticks this tradition continues in Patiala where craftswomen from neighboring villages make and sell the handmade nala to traders in the Quilla Chowk area of the city.

Continuing from as far back as can be remembered the fibre of hemp bark (nalu) has been extracted and processed in Nepal. It is used for a multitude of purposes including the making of strong ropes and bags, and the weaving of namlos - headbands to support baskets - and dumlos - used to tie or tame animals and many other purposes. Hemp, a tropical plant that grows to a height of about 7 to 8 feet is cultivated extensively in the eastern terai region of Nepal. Its bark is thick and is the raw material source of the fibre. It is also commonly called jute/ nalu fibre.

- white bast fibre from the stem;

- oil from the seeds &

- narcotics

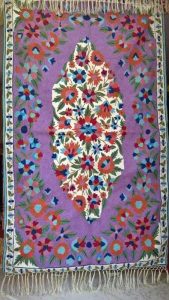

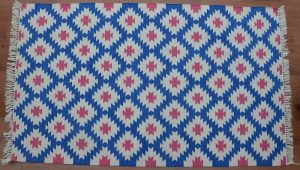

Woollen namdas are prepared by the Pinjara and Mansuri community of Kutch. They are made in locally available desi wool. Impurities in the locally purchased wool are removed by hand and the wool is then spun and dyed in yellow, orange, red, maroon, blue, and black. The wool is turned into ropes by rolling it on the surface of an inverted pot. It is then converted into attractive wall hangings, horse and camel saddles, torans, caps, and floor covering. The dhurries are floor coverings made from wool and cotton textiles. The warp is always in cotton of 2x 10 counts, and the patterns are of horizontal stripes. Although the craft of making felted rugs originated from Central Asia, It has been carried forward as a legacy by the communities in Kutch, Gujarat. The Pinjara and Mansuri families in Kutch are skilled in the technique of felting. The base fabric of these rugs is made from wool, over which patterns are woven. The most unique aspect of the Kutchi namda is the unique inlay patterns. The namda pieces are often embellished with tassels

Floor coverings other than woollen carpets are known as namdhas and gabbas. Namdhas are made of felt and embroidery and appliqué techniques with dyed wool are used to embellish these. The designs are floral, geometrical, and folksy. This is a cosy and colourful handmade felt rug that makes an excellent and rather inexpensive floor covering in winter. These namdhas are very popular owing to the embroidery on them --- chain stitch in woollen yarn is done by hand with a hook or needle. A namdha is supposed to have originated during the 11th century when the great Mughal Emperor, Akbar, was on throne. Namdhas are generally available in 3 x 5 and 6 x 4. Rugs can also be made to order. Gabbas are floor coverings made out of old blankets. Appliqué work is often done on it. The colours used are muted, though warm tints are used. Gabbas are popularly known as poor men's carpet and are rated as a common utility article by all classes of people. Creative genius has evolved it into an artistic substitute for more expensive carpets. Druggets are made from cotton and woollen waste. The same carpet designs are used as they are made by the same weavers. Hook-rugs are also establishing themselves in India.

Ply-splitting, one of the simplest forms of textile structure, is a commonly used technique the world over for the weaving of animal trappings; in Nepal, however, it is attached as a headband or tumpline to the traditional carrying-basket, dhoko, which is carried by porter(s) on their back(s). The namlo is strong and firm, yet flexible, and moulds itself comfortably over the porters forehead. It is also frequently used as a back strap as it serves the additional purpose of helping to balance evenly the load on the back. These headbands are made of varied fibres, including allo, jute, and sisal or bark, though allo produces the strongest bands. The broad width of the namlo rests comfortably on the porters head; its importance can estimated from the fact that often porters are required to carry twice their own weight of load in the baskets that they lug uphill along sleep inclines. The Imperial Gazetteer of India (Provincial Series) on Nepal in 1908 states that:

The Bhotias carry enormous loads. It is by no means uncommon for a man to take two maunds, though one maund (8 lb.) is the regular load, and this has to be carried over hills several thousand feet in height where the paths are of the most primitive construction. The Bhotias always carry loads on their backs supported by a strap across the forehead....Being porters - like trading and army service - offers a way of earning the supplementary income that is so essential in areas of scarce subsistence-level farming.

Narayanpet is a town, 70 km away from Mahbubnagar in Telangana. The origin of the Narayanpet Saree can be traced back to the period around 1630 AD. The saree is a fine count cotton saree normally woven with 60's–80's yarns both in the warp and weft. Small extra warp geometrical designs are woven in the border with zari/art silk. These sarees are woven on fly shuttle pit looms fitted with the lattice dobby. Various types of colourful silk saris, with intricate brocade work in silk and zari, are woven at Narayanpet. As the silk threads are not of a very high count, the saris are both light-weight and festive.

The sources of natural dyes are flowers, berries, roots, rinds, wood, lichens, and the gall of plants which yield earthy colour tones of browns and buffs. Crimson and scarlet hues are obtained from the female insect, cacti and lac, which is found encrusted on the branches of some specific trees. Purple is obtained from the trumpet shell.

The British introduced synthetic dyes in India in the nineteenth century; the use and production of natural dyes began to decline from that point. Apart from textiles, vegetable dyes are also used to colour wood, mats, basketry, pith, ivory and leather. The names of colours prevalent were piyaji (onion skin), sumai (blue-black), basanti (yellow), asmani (sky-blue), neel (blue), badani (beige), sonali (golden), abir (red), and dhani (yellow green). Botanical Name Color Part Used

1. Acacia catechu Maroon, Brown Wood extract

2. Artocarpusintegrigolia Yellow Sawdust

3. BixaorellanaOrange Seed

4. PunicagranatumKhakiRind

5. Curcuma longa yellow Rhizome

6. Diospyros peregrinePink Fruit

7. Nyctanthesarbortristis Orange Stem

8. TagetespatulaYellow Petals

9. Acacia ArabicaPink Sawdust

10. Terminaliachebula Grey Ripe and unripe fruit

11. Rubiacardifolia Brick Red Root

12. Terminaliaarjuna Beige Bark

13. CeriopsroxburghianaSalmon Pink Bark

14. CedrelatoonaPink Sawdust

Some other key dye-sources are as follows:

- Yellow is obtained from root of the plant Morindapersicalfolia. The roots are cut and boiled along with salt; the resultant solution dyes the yarn an even shade of yellow.

- Brick-red is extracted from the leaves of the plant, Rhyncosatiasp; the leaves are ground into a paste to which lime juice is added gradually till the colour turns brick-red.

- Black is obtained from the plant, Leniagrandis by crushing the fruit. The fruit is boiled in water with salt till the solution turns gray. The yarn is then immersed and boiled in this solution till it turns gray; after being buried in clay soil for 24 hours, it turns black.

- Orange is obtained from the bark of Phyllanthusemblica, Leniagrandis and Artocarpuslakoocha. The bark of the three plants are combined in equal portions and soaked in water for 15-20 days. When the solution turns orange, the yarn is immersed for a few hours, stirred occasionally, washed and sun-dried.

- Charcoal-gray is obtained from the plants, Careyaarborea, Leniagrandis and Eugenia Jambolana when the bark of the three plants are combined in equal portions and steeped in a vat for 15-20 days. When the solution turns orange, black potters clay is added in 1:6 proportion. The yarn is soaked for 5 hours, washed and sun-dried.

- Red is obtained from Morindapersicalfolia by powdering the root and mixing it with water. The yarn, treated with mustard oil, is soaked in the solution for three days, wrung and dried in the sun.

- Red is also obtained from the seed of the plant, BixaOrellana where the seeds are soaked with turmeric paste and lime along with yarn for three days. Yarn is then boiled, washed off and dried. The process is repeated to deepen the colour.

- Dark brown is obtained from the plant, cocosmucifera from the coir, where it is boiled with a turmeric powder till it turns brown. The yarn is soaked for a few hours, wrung and sun-dried.

- Pink is obtained from Ceriopsroxsburghiana by boiling the bark with soda till the solution turns pink. Yarn is boiled in it for dyeing, after which it is washed and dried in the sun.

- Blue-black is obtained from the leaves of Indigoferasumatrana where the leaves are soaked in the water and fermented. A small amount of bamboo ash is added to it. Yarn is put in and boiled till it turns blue-black; repeated boiling deepens the colour.

The vessel type used for dyeing yarn has to be chosen carefully. Earthenware is suitable, but its porous nature results is absorption of liquid dyes. Each dye has to have a separate container. The best containers for dyeing are those made of copper or stainless steel; these materials do not react with the dye stuffs and are very hardy. Earthen vessels are ideal for scouring, washing and bleaching. Natural dye solutions like kasmi and neel can be stored in earthen containers. The size of the containers chosen depends on the amount of material to be dyed at a time.

Cost benefit analyses have shown that vegetable dyes are more economical than imported chemical dyes; catechu, the most expensive of the natural dyes is well below the cost of an equivalent synthetic dye. The average costs of natural dyes are 10-20 per cent that of synthetic dyes. If use of natural dyes increases, it will help in the revival of traditional crafts, based on indigenous sources.

The art of dyeing in Nepal has an ancient past. Historic evidence based on a study of paintings and religious and cultural records indicates that natural dye-stuffs were used not only for the colouring of textiles and yarn for clothing, but also for dyeing yarn used in making tapestries. The collections of costumes, paintings, and tapestries that have been preserved in the stores of temples and monasteries in Nepal bear evidence to this.

- The best known and the most commonly used Nepali natural dye is madder (Rubia cordifolia Linn., (majitho) which yields colours ranging from orange-gold to deep red and light pink. The importance of madder for dyeing, both domestically and commercially, is indicated by the fact that the Sherpa word for 'dye' in general is tsoe, a word that is used interchangeably for madder; all other dyes have their own specific names. Traditionally, madder root, extracted mainly in the autumn months, is crushed and dried, mixed with an alum mordant, and used to dye the robes of Buddhist lamas. Its importance is indicated by the fact that in the nineteenth century it was bartered between the Tibetans and Nepalese in exchange for borax and rock salt.

- Also popular as a natural dye is the brown shade used for the dyeing of the commonly worn kogita textile. Traditionally, the colour of this light brown fabric is obtained from a species of the betel nut (higoye), the buds of the naranpati tree, ram tilak colours, and red clay, all infused in a copper vessel called phosi. The mordant used to make the brown dye for the kogita fabric permanent is an extract of citrus fruits such as lemon. The use of the copper phosi plays an important part in the dyeing process as the metal helps in brightening the colour(s) derived.

- The dye around which the most myths, traditions, and legends are built is the washi, a dark blue dye. A unique example of rock-dyeing, the washi is traditionally obtained in the form of hard clay from the Pharping area. This rocky substance is finely powdered, mixed with water, and preserved in earthen jars for several months. Often, the earthen jars in which the deep and rich blue colour brewed were preserved by the ranjitkars inside their homes - the chhipako ghyampo or the ranjitkar's blue washi earthen jar was thus a long-standing tradition among the dyers in the Katmandu Valley. This clay jar has come to possess a ritual significance among the dyers as it was regarded as a symbol of 'Bhairab', the terrifying form of Lord Shiva. Worshipped by the dyer community during the dasain festival, special tributes are paid on the day of bijaya dasami, with the prasada or auspicious offering being made in the form of threads that are distributed to family, relatives, and friends. These earthen jars, traditionally a common sight in the Humata, Jaisidewal and Majipat localities of Katmandu and the Tangal and Sougal toles of Lalitpur, are now rare.

- The bark of the gular tree (Ficus glomerata Roxb) is used in preparing a deep black dye.

- In the Mustang region, the tinchu plant yields a pink and yellow colour, while the higway nut is traditionally boiled in water for 2 to 3 hours to yield a reddish saffron colour. Various other naturally occurring dyes made from locally available plants like padmachal, the bark of the okhar, walnuts, and the roots of the chulthe amilo are tradition dyes in this area.

- The bark of the soap nut plant, ritha (Acacia concinna DC), which grows in parts of the eastern, central, and western regions of Nepal has been used for dyeing and tanning fishing nets for generations. When an infusion of its leaves is combined with turmeric (haldi) it yields a green dye.

- The asuro (Adhatoda Vasica Nees) or Malabar nut is used for dyeing coarse cloth yellow; in eastern Nepal, the leaves of the lodh (Symploc Spicata roxb) are powdered and used to make a yellow dye.

- The bark of the English Yew (dhangre salla) is used in Nepal to produce a red dye; it is also used by the Brahmin caste of Hindus for marking their foreheads with their caste marks.

- Traditionally, in Nepal, the dyeing of ram wool used for making the galaincha woollen carpets was done with a mineral blue dye known locally as ramje. The process of dyeing followed in the northern extremes of Nepal is arduous and complicated and has remained unchanged till today. The mineral clay that yields the dye is found in both the Mustang area and in western Nepal; it is extracted and powdered, boiled with local beer (jand) in a copper vessel, and then mixed with goat dung. This solution is allowed to ferment for about a month. Through this fermentation process a blue dye is obtained.The woollen yarn to be dyed is first cleansed with warm water to remove all impurities and then infused in the dye bath. The duration for which the wool is soaked in the dye solution determines the depth of the blue shade that is obtained. If a very light shade is to be imparted, the wool needs to be dipped only for a few minutes, whereas a deep-blue colour requires a half-hour soak. On being taken out of the dye bath, the wool is hung on wooden poles to dry in the sun and wind. The colour obtained is permanent.

- For a yellow dye, a flower that blooms in the Jomson and Marpha regions of the Mustang district is used. The flowers are collected, dried in the sun, and powdered. The powder is boiled with water, yielding a yellow dye. Prolonged soaking in the dye bath imparts a deep yellow colour, after which the wool is dried in the sun.

- The bark of the okhar tree is used in dyeing wool brown; this natural dye is traditionally used by radi-makers.

- The bark of the kalosiris (Albizzia lebbeck benth) or Indian walnut that is found in eastern, central, and western Nepal yields a shade of dark red when mixed with an alum mordant.

- The bark of the bhojpatra (Betula utilis D. Don) - the white Himalayan Birch tree found in eastern and central Nepal - yields a yellow dye when mixed with an alum mordant.

- For the dyeing of pakhi wool, sour milk (mahi) is boiled and a red dye added to it. Wool is immersed in this acidic solution and boiled for three hours in a brass vessel; this imparts a red colour to the wool. If the wool it to be dyed black, it is boiled with an aqueous solution of common salt and black dye. About two to three kilograms of common salt are required to dye 20 meters of pakhi wool.

- Some commonly used natural dyes - used for dyeing both wool and cotton - include the soma plant, whose roots yield a yellow colour, and the kilche roots that grow around Bagling, which, when crushed in a mortar along with the locally made wine and water, yield a shade of grey.

- The bhringraj (Eclipta alba Hassk) or daisy flower that grows all over Nepal is used not only for dying cloth black but also for imparting a rich black when the body is tattooed.

- The root of the bhanta plant (Geranium nepalensis Sweet), which grows in the temperate Himalayas is used both as a red dye for textiles and for colouring medicinal oils.

- The sigada (Trapa bispinosa Roxb.) is used for making red powder that is used during festivities.

The discovery of the first synthetic dyes in 1856 and their subsequent introduction into undivided India by the British had disastrous consequences. It led to the rapid decline in the use and commercial production of vegetable dyes. By 1861 the formula for alizarin, a synthetic dyestuff, replaced the vegetal madder root for all shades of red. Chemical indigo was developed in Germany in the beginning of the twentieth century, after 12 years of research it was simply a matter of time before it entered with similar negative consequences for natural indigo. Thus it took barely a hundred and twenty-five years to eliminate almost all traces of natural dyes from the Subcontinent. The skilled craftsmanship of centuries was inevitably eroded because a cheaper alternative, requiring little or no skill, was made available in the captive colonial market. Dr N N Banerjee in his report on "Dyes and Dyeing in Bengal" in 1896-97 recorded Dhaka, Rajshahi and Bogra as dyeing and weaving centres. Nesbitgunj near Rangpur, was known for satranjis of dyed cotton. Indigo vats scattered all over the country confirm that substantial vegetable dyes were still being used at that period.

MAT WEAVING The weaving of mats of various sizes and shapes, and the making of containers, food-covers and lamp shades from reeds or strips of dried stems of coconut palm leaves, is practised in many islands. Cadjan weaving is also common. Cadjan is a mat made from coconut leaves sewn together with coir rope. It is used for thatching houses and for fences. In some villages, the bundles of reeds that provide the thatch for rustic resort cabana roofs, are stitched together by women using long wooden needles and coconut fibre thread. Since a roof made of thatch needs to be replaced or re-done often, it is more expensive to use the local product than imported roofing material. Sataa, a soft lattice mat woven from thin strips of dried screwpine leaf, is popular for use as a ceiling in many resort cabanas. On Kihaadhoo, in Baa atoll, women and older people can be seen at work in their cottages fashioning sataa for sale. Woven mats known as kunaa are now made only in Gaaf Dhaal - they too are found to be dwindling. (On Bandos Island mat weaving is demonstrated by craftspeople who offer the products for sale.) While documenting the weaving techniques and the plants used for fibre and dyes it has been found that a number of traditional designs have not been woven for many years. Collecting the raw materials, processing them and weaving a mat takes weeks and involves hard work not consistent with the returns.