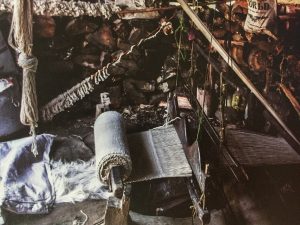

The Chunere tribe of Uttarakhand work on the gharats, the traditional watermills, on a small patch of land in the middle of the river Kosi flowing through Garjia village, crafting wooden utensils called Theki. The water diverted from the river through a stone embankment extends towards the watermill through a wooden chute. A wedge inserted to the end of the chute directs the water to the turbine runner producing energy, enabling it to move. It is here that the master craftsman of the Chunere tribe carves and shapes the moving log with his instruments, the helpers do the finishing. This watermill is a centuries old part of hill culture, serving local needs, mainly for grinding maize, wheat and rice. Here the Chunere tribal's craft utility items for the villagers. Every year in December, a handful of craftsmen arrive from Bageshwar, a holy town in the Kumaon Himalayas, and live and work by the river till March. The only community to get a permit to cut trees in the forest, they procure sandhan wood to make vessels used by the locals as the wood has medicinal qualities. Locally known as Theki and weighing two-three kgs each, they craft pots for pickles, for storing milk products including curd as it doesn't sour in these pots, flower vases and local musical instruments like the Hurka. The items are sold in the nearby villages of Tehri, Uttarkashi, Almora, Nainital and Pithoragarh. As their agricultural yield is not enough to sustain them for the entire year the Chunere group live and work, away from their families for these months to make ends meet by crafting and selling these wooden vessels. They take loans to pay the forest department for cutting trees and buying rations.

Thewa is a jewelry craft practiced by a handful of artisans who specialise in the art of fusing filigreed gold sheets onto glass. The craft of thewa is practised by these hereditary artisans in the small fortified town of Pratapgarh in district Chittorgarh of south Rajasthan and Rampura in Madhya Pradesh. This unique craft uses plaques of glass as its base material. Till today the tradition of using red, green or blue glass continues. The technique of thewa has been used to create marvellous ornaments, plates, trays and jewelry, as well as small objects for daily use.

Craftsmen work sitting on the floor on mats. His work table is sufficiently low enough (1' in height) to be comfortable. Worktable dimensions in terms of the available surface area are approximate 1.5'x2.0'. The surface is with a slight slant towards the craftsman.

Another closed wooden box of similar dimensions is kept near to the work table which stores the tools, implements and certain raw materials. When the craftsman works, he prefers his tools to be placed within easy reach.

About 1.5m. away from the work table the furnace unit is set up in a corner with its relevant tools kept near it.

Craftsmen work sitting on the floor on mats. His work table is sufficiently low enough (1' in height) to be comfortable. Worktable dimensions in terms of the available surface area are approximate 1.5'x2.0'. The surface is with a slight slant towards the craftsman.

Another closed wooden box of similar dimensions is kept near to the work table which stores the tools, implements and certain raw materials. When the craftsman works, he prefers his tools to be placed within easy reach.

About 1.5m. away from the work table the furnace unit is set up in a corner with its relevant tools kept near it.

- Gold

- Silver

- Glass

- Solder

- Iron wire

- Beads (plastic)

- String (nylon) embellishing raw material.

- Copper sheet

- Geru

- Coal

- Chapdi

- Dhool (dust)

- Oil(cooking)

- Mica

- Sulpuric acid

- Reetha (araknut)

- Cells

- Dotting tools: There are dotting tools of different sizes of two types one type is just a pointed dot and the other is a circle with a dot inside. These tools are used for making eyes, borders, flowers etc.

- Double lining tool: This tool is used to line the borders. Double line is made at the border to put decorative elements between the two lines. This is purely aesthetic and could have some immense of religion.

- Border pattern tools: These tools are specially fashioned for making repetitive patterns as border.

- 1st step drawing tool - Kandarna: these tools are not really fine tipped as compared to the other tools. These tools are used to outline the figures on gold. These tools are flat tipped (3mm.) and are used continuously i.e. the tools are not lifted much to create continuous lines.

- 2nd step drawing tools - Chirna: These tools are used to decorate the outlined figures and to give them details. A lot of combinations of tools are used to achieve the best results. These tools include a tool which I the same shape as Kandarna but the width is 1.5mm.

- 3rd step drawing tools - Jali tools: These tools are used to cut the Jali in the gold design. These tools are of different cross-sections. There is a tool like a scooper, one sharp tool to cut sections and take material out.

The soldered piece is removed and dipped in diluted sulphuric acid for sometime. Then, the mica sheet is peeled off using the Chimtas. To remove any crimps on the gold sheet it is placed face down on a hard surface and the Vada is lightly hammered.

Pieces of the solidified Ral are placed within the Vada on the gold sheet. This is then heated for the Ral to melt. The melting of the Ral is done by placing the filled wire and gold sheet on a flat iron sheet and placing a mica sheet over the Vada and gold sheet. This is placed in the furnace. The furnace is made of iron sheets. Coal is used as a fuel and pieces of burning coal are held over the job with tongs and provide heat from above. A blow pipe is sometimes used for direct heating. The softened Ral is spread all over by pressing it. It is lightly hammered to pack tightly within the Vada and gold sheet. Thus, the gold sheet acquires a suitable base on which it can be worked upon. The Ral is then suddenly cooled by dipping in water to set it. The extra gold is clipped-off form the sides of the Vada. The outer edges of the Vada are then rubbed on a grinding stone. The wooden block with the Ral is heated to melt the Ral so that it can be spread and flattened. The A wet piece of thick paper put on it cool and is left thus. Now the decoration of the gold sheet starts. The first stage, Kardarna, is when just an outline of the motif is etched on the gold sheet. The second stage involves detailing i.e. eyes, ornaments etc. This is called Cheerna. The third stage is when the Jali is cut. This is a delicate process and the waste is collected in a small piece of paper. The waste is in the form of gold sheet plus Ral which is later melted. The gold melts and the Ral burns out. After cutting the Jali, the block is heated so that the Ral melts a little and when it is melting, the Jali is lifted slowly with a tweezers. After this the glass is etched with the same metal as in gold in negative i.e. the portion which is left in gold is etched out in glass. Then a solution is applied to the gold Jali and the Jali is placed on the gold etched glass and the glass is heated. This fixes the gold on glass.

- Traditional method (Craftsman from Pratapgarh)

- Contemporary Method (Craftsman from M.P.)

Traditional method: A glass piece is cut with a diamond cutter to a suitable shape and size to be placed inside the Vada. This arrangement is covered on the side of the gold work with a mica sheet (the mica acts as a non stick surface). A heavy steel stab is placed over the mica sheet. This whole structure is placed again upon a similar sheet slab in the furnace. Due to heat and pressure of the steel block it is probable that the gold is fused with the glass. It happens in a manner in which the gold and the base glass acquire a common surface with no two distinguishable levels.

The work is taken out of the furnace after the glass is seen to turn red hot for a few seconds. It then left for cooling. Contemporary method: The glass piece to be used is first etched with the design with the help of a diamond cutter. This design is transferred on the gold sheet; by holding the etched side of the glass in a non-oxidizing (yellow) flame, it is covered with a layer of carbon (soot). The etched surface is then pressed on the gold sheet to get a print on it with help of this reference a duplicate of the design is on the gold sheet which gives the Jali work in gold. FIXING OF THE JALI WORK ON ETCHED GLASS The etched surface of the glass is coated with a solution which possibly acts as a adhesive when heated. The gold work with the Vada is placed on the etching and fit slowly. This arrangement is placed in the furnace. After the gold fuses with the glass it is removed from the furnace and left to cool. The gold fixes with a level below the surface of the base glass and the etched edge of the glass can be easily felt with ones fingers. FIXING OF THE GLASS IN GHAR After the gold plated Ghar is ready, the base is fitted with iron wires (stuck with adhesives; synthetic) to give the glass support inside the Vada the glass with gold is then placed and the Vada top is rested on the glass. In case the piece has to be stung holes are drilled in the sides of the Vada for the string to pass through. Only gold sheets of the highest purity are used, for this lends itself to the thewa technique. The artisans treat all gold to remove impurities before rolling out and cutting the sheets, usually of 40 gauge thickness. 'As the work requires intricate detailing and skilful fusion of the gold into the glass base the wastage is high', says Ganpat Soni, a National Award winner and master in the technique of thewa. 'Overheating can break the glass or melt the gold. Alternatively, if not treated properly the gold filigree does not fuse well and soon comes off.' Talking about the initial struggles Soni says: 'It is only after years of intensive experimentation and many failures that the technique can be perfected.' Soni now guarantees 98 per cent quality. The artisans at Rampura have been using Belgian glass, from old windowpanes of houses and buildings, as the base for thewa articles; however, this source has now been exhausted and finding glass with the right colours is becoming increasingly difficult. As a result, thewa pieces can now be found in a new range of colours and materials: lemons, whites, blacks -some original, some obtained by using plastics. Artisans are also experimenting with other metals, including silver.

- Tourists (Indian as well as foreign)

- Private dealers (not local)

- Government officials (for sale in government emporiums)

- The local Market.

The craftsmen are also called for exhibitions in different cities where they sell their products.

This process involves resist-dyeing on woollen cloth. Chief centers for practicing this craft are the Nubra valley and Sabu. Products like panels for garments called Nambus, belts called skerekh and narrow belts are created under thigma. The tools used for practicing this craft are thread and cord.

Very few craftsmen are practicing this craft today in Madurai, Tamil Nadu. Practitioners belong to Pilamar caste and are a close-knit community. The main product of the decorated temple chariot is the ther seelai. Appliqué hangings are found on temple chariots and were used mainly as thoranams/lintel pieces during festival processions. When they are tubular in shape they are thombais and they look like colourful pillars as they hang down the sides of the chariot. They are mainly made of cotton or felt in rich, bright red, yellow, white, black and cobalt-blue The sacred images used in these hangings are of Gods and Godesses like Durga, Ganesh, Kartikeya and Shiva.

Very few craftsmen are practicing this craft today in Madurai, Tamil Nadu. Practitioners belong to Pilamar caste and are a close-knit community. The main product of the decorated temple chariot is the ther seelai. Appliqué hangings are found on temple chariots and were used mainly as thoranams/lintel pieces during festival processions. When they are tubular in shape they are thombais and they look like colourful pillars as they hang down the sides of the chariot. They are mainly made of cotton or felt in rich, bright red, yellow, white, black and cobalt-blue The sacred images used in these hangings are of Gods and Godesses like Durga, Ganesh, Kartikeya and Shiva.

This is done on coloured paper which is used as the base. The figure is traced out with small iron nails fixed on the board with coloured paper. The thread is fixed on the nails and the entire figure is completed with this thread work. The themes for the craft are religious with deities like Lord Jagannath and other designs like lotus, peacock, and the like

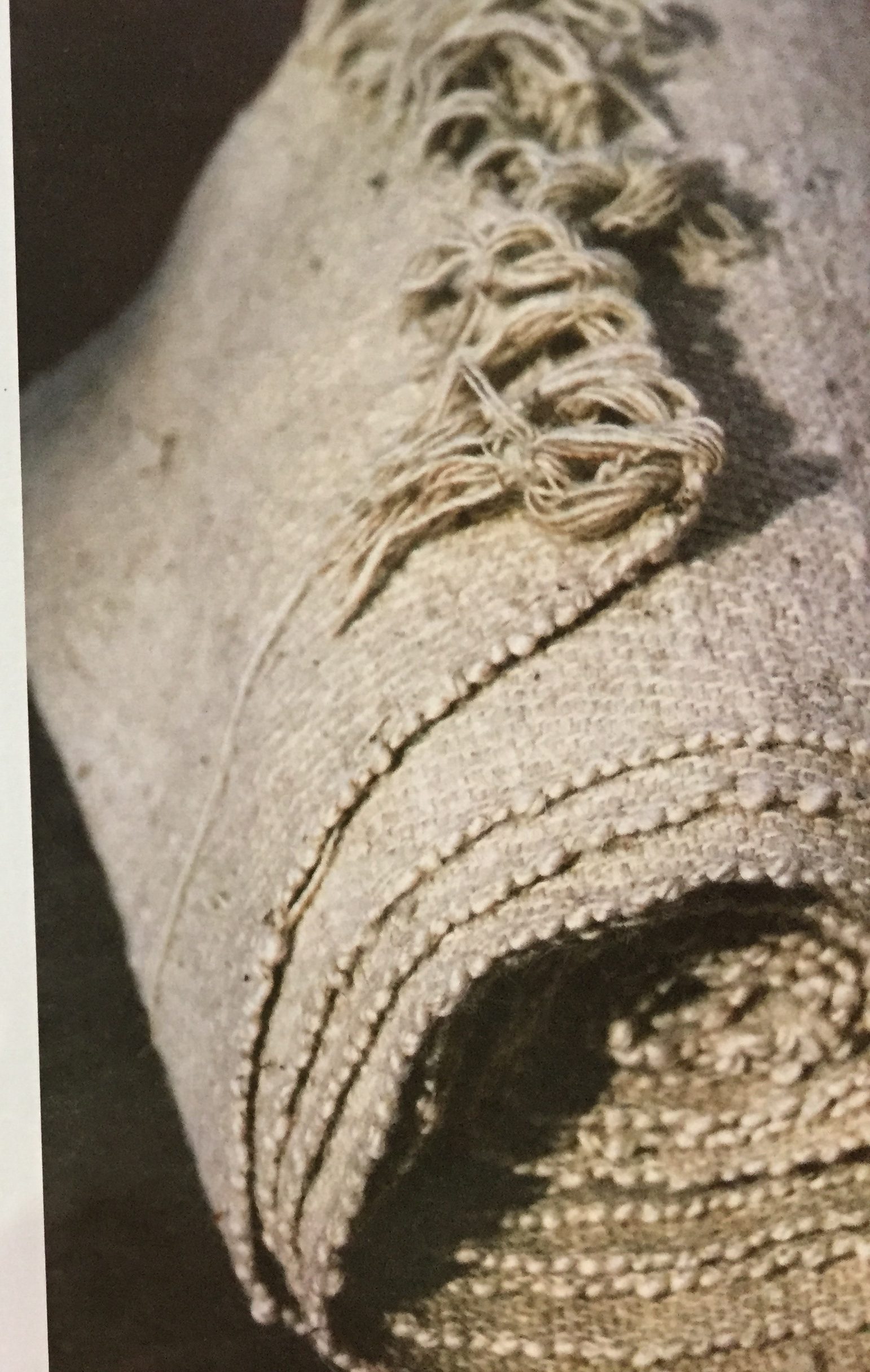

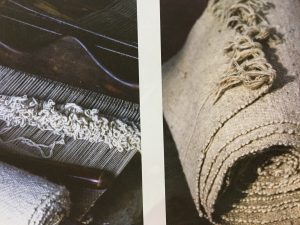

This woolen blanket is traditionally worn by the Shauka women. It is however much lighter and the fabric is brushed from inside which gives a fuller texture to keep the wearer warm in old regions. Thulma is woven either on a pit loom or the frame loom. It is woven in long strips that are cut and stitched together. the edges are finished with a blanket stitch. the colors- off white and grey are of the undyed wool sheared from the local sheep.

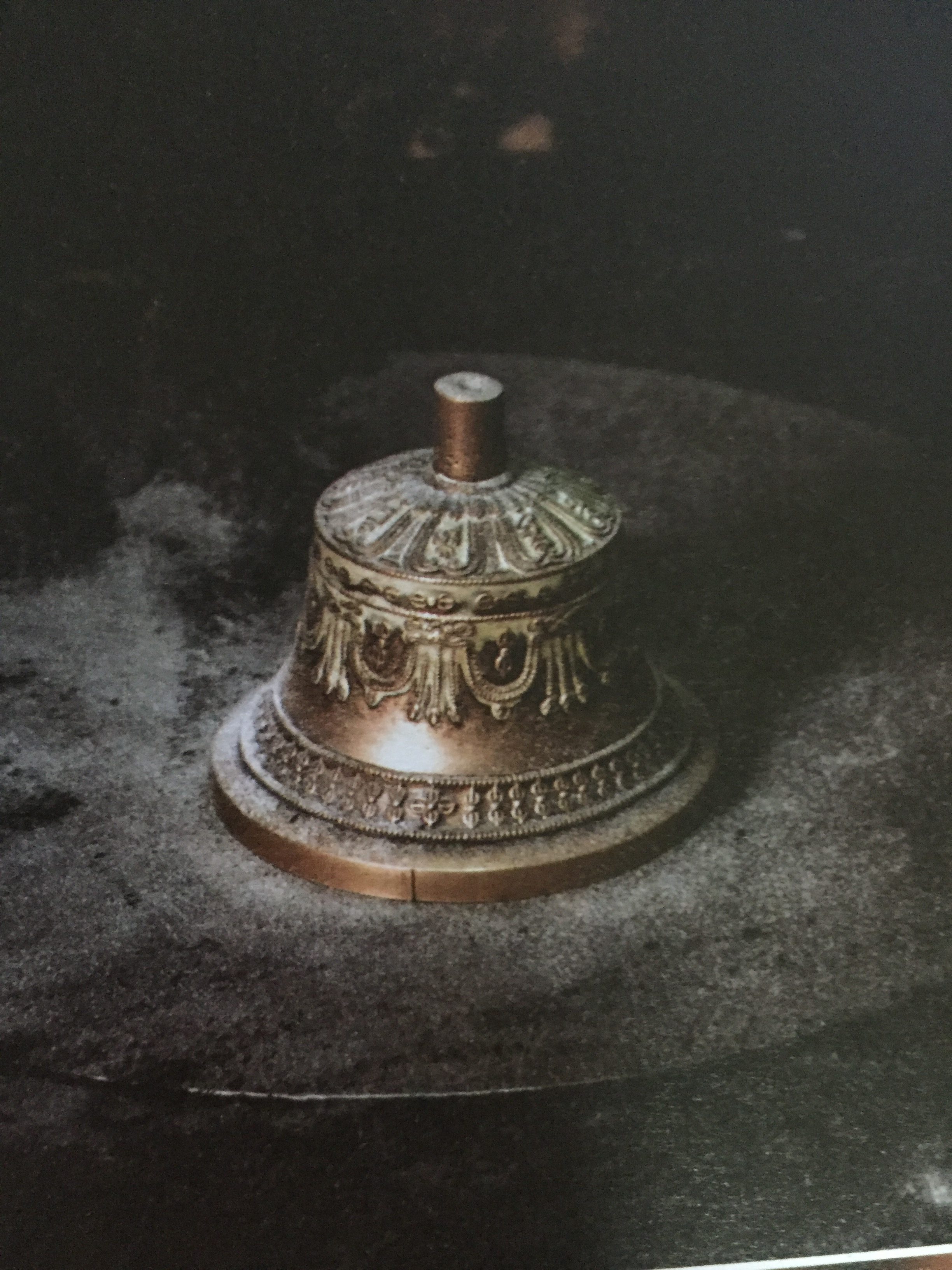

Lingstang in Manduwala, 30 km from Dehradun, is a settlement of Tibetan people living in exile. In 1959, the Chinese overran Tibet and began to serve the cultural and religious persecution of the people,. causing an exodus of the Tibetans with their spiritual guide, JHios holiness, the Dalai Lama. In Dehradun, the statues and implements are sand cast. The foundries are in Lingstang and Dharampura, Designs of ritual implementations such as the Drilbu and Dorje are ancient and have specifications that can not be changed as they are used for prayer.

The tie-and-dye technique practised at Rajasthan is both similar and different to the technique practised in Gujarat. At both centres it is the fabric that is tied and dyed to the design's chosen pattern. A large number of colours are used because once the base colour is tied in, a lot of colours can be applied on to the fabric at different stages and then tied and removed progressively. The motifs that are used are flowers, leaves, creepers, animals, birds, and human figures in dance poses; geometrical patterns are also common. The designs are given names like mountain design, kite design, and dol design. The dyeing is done in matching or contrasting colours. Dots are used to make up the designs. Do-rookha dyeing or different colours on either side is also practised by the craftsmen here. The lehariya technique has long lines or bands in various colours found all over the body of the sari or cloth. The lehariya cloths have their own names depending on the designs: pancharangi (five-coloured) and satrangi (seven-coloured) are common. Bandhanis are linked to various seasons, festivals and rituals for which there are specific designs and colours.

Woollen shawls are also dyed according to local traditions. The designs preferred include geometrical borders, large sunburst-like dots, and motifs like the scorpion and peacock. Traditionally, unmarried girls wore black shawls with orange dots; married women wear red and black. This craft is now being practised by very few artisans.

The Bandhani found here is unusual and very attractive. The main centres are Tarapur and Umedpura; Bhairongarh is a smaller centre. The Gambhiri river which flows in this region has its banks full of drying bandhani fabrics. The popular motifs include the dana pattern that is formed by chains of grain on the body of the fabric with elaborate designs on the borders and pallu. The gaps between the bands of dotted lines are filled with motifs and the borders have zig-zagging lines on them. The designs on the body of the chunris can be squares dots, clusters of dots, flowers, and birds. The colour combinations of the saris or chunris are mainly indigo-blue and red. The bandhani owes its attractive appearance to contrasting bright colours, lines, and trace-figures. A woman's upper garment made in the bandani style called pillya. This is a speciality of Jawad. The background colours are mainly red and the motifs are leaves, flowers, dolls, and elephants. In Jawad, hair strings or parandas in the bandhani style are also crafted from cotton yarn in several colours.

Tie and dye work is done in Madurai in the southern part of Tamil Nadu, by migrants from Saurashtra, Gujarat who have long since settled here. Backgrounds are typically in the dark colours preferred in the south like red, black, blue and purple and the tie and dye pattern is found all over the body of the saris. This style of tie and dye is locally called Chungidi. The specialty here is the kolam or rangoli patterns. The kolams are all geometric in nature and the borders of the sari are in contrasting colours.

The traditional patola is a double-ikat silk, with intricate five-colour designs resist dyed into both warp and weft threads before weaving. In the patola both warp and weft is resist dyed in a manner that, when woven, the elements of patterns on warp and weft mesh completely and perfectly. A slight 'run-on' in texture - a flame effect - is often there, though in a pure patola this 'run-on' should be almost imperceptible.

- Purely geometric forms (e.g.: the navratana bhat or nine-jewel design)

- Floral & vegetal patterns (e.g.: the pan bhat or pan-leaf design/ chabbdi Bhat or flower-basket design)

- Designs depicting forms (nari or woman/ kunjar or elephant/ popat or parrot)

The colours are of the earth, of stones. The modern patola often has the designs are created in the weft threads only. This is less labour intensive and hence less expensive.

Tikuli or Bindi made up of gold and silver foils on solid glass was once a flourishing trade during medieval;l times and Patna, Bihar being the Centre. Due t gradual loss of royal patronage this art almost became extinct. Tikuli Art owes its revival to the famous painter Upendra Maharathi. Originated more than 800 years ago in the Patna District of Bihar. The word 'Tikuli' is derived from the word 'Tikli' which is a dot like embellishment with glass base and gold foils in a variety of designs used by most of married women for adorning their forehead. The making of Tikuli Involves melting of glass, blowing into a thin sheet and making and adding traced pattern in natural colors. Afterwards it is embellished with gold foils and jewels. In the olden times, Tikulis were mainly used by queen and aristocrat women. Beautiful hand crafted Tikulis were revered as proud possessions of the women. Now a days, the art of Tikuli making has been fused with Madhubani Paintings to make decorative wall plates, coasters, table mats, wall hanging, trays, pen stands and other utility items. This has increased the facets of this art and the scope of creativity for the artists. the fusion has not only created a new charm to the art but has also imparted an economic value to the produce.

Tilla refers to gold or silver zari and dori refers to silk thread in the Tilla and Dori embroidery of Kashmir. Textiles like pherans, saris and shawls are produced using this technique.

In Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, the red sandal wood (red sanders or raktachandan), so called due to its rust-red tint, is used to carve dolls. This wood is hard and elastic, and resists white ants and fire. The dolls made here have a natural finish and are notable for their powerful modelling and simplicity of form. The toys consist mainly of reproductions of religious figures in the traditional classical style seen in sculptures and are perfectly replicated in small sizes. Some folk figures are also made in pairs, with close attention being given to clothing and ornament. Each pair has a special name. The dancing figures which are highly ornamented and beautifully chiselled have a remarkable dignity about them. Possessing sharp features, these dolls are unique in style.

The Toda women in the Nilgiri hills of Tamil Nadu have their own distinctive style of embroidery called pugur, which means flower. The embroidery is done on the shawls conventionally worn by men. The shawl, called poothkuli, has red and black bands that end at intervals of six inches. The look is embossed and the embroidery is done between the gaps in red and black. The most important motif is that of the buffalo horn as the Todas venerate the buffalo, other important motifs include the little box called mettvi kanpugur and the design named after the ancient priest of the Todas called Izhadvinpuguti. There are other motifs named after wild flowers; and a quaint motif named after a girl who slipped and fell off the precipice. This dramatic style of embroidery, done exclusively by Toda women, uses red and black threads on a white background. The work is so fine that it is often mistaken as a weave at the first glance. Girls learn this art from their mothers at a very young age. It is an intricate form of needlework embroidered on a shawl in continuous bands of lengthwise strips, rather than across the width, and is called Pootkhull(zh)y. Toda embroidery is reversible, so the shawl can be used on both sides. The Todas consider the “rough” obverse side, with its generous looping of threads, as the right or display side, and not the far neater, reverse side. The base fabric is a rough off-white cotton cloth woven specially for the Todas by weavers who known as Kolas (another tribe living in the Nilgiris). These weavers used to barter cloth for buffaloes, bulls or calves. Now, they sell them for cash. The design patterns of the Toda embroidery are mostly symbolic, ranging from floral motifs to animal and human figures. It is done in the counted thread technique, following the right angles of the warp and weft threads of the coarsely woven material. The necessary stitches are executed according to the required pattern. This gives the impression of a woven rather than embroidered pattern.

The shadow play or puppet show with leather figures is an art form of great antiquity. References to it are found as early as the 12th century. Shadow play flourished in different parts of India and the figures of the various characters of the play were designed in leather, with the play being performed by projecting the shadows of these puppets on to a cloth screen. In Kerala, Tolpava Koothu (tol means leather, pava means puppet, and koothu means play) originated in the Palaghat district where it is still performed in the temples of Bhadrakali as part of the ritualistic worship of the goddess. Odisha too has a tradition of leather puppets and of puppet shows known as Ravanchaya While in Karnataka the puppeteers are well versed in music and in the themes of the great epics. Andhra Pradesh has several families of traditional puppeteers called tolubommalata. The techniques used to produce the puppets is complex. Goat or sheep leather is used and skin is first stretched taut and is nailed at the corners to keep it in position. It is then smeared and rubbed with ash, and exposed to the sun till it is dry. The puppet figure is then drawn on the leather and cut out with a fine chisel. Ornaments and clothing are drawn by drilling different kinds of holes in the skin for which special pointed chisels are used. Colour plays an important and ritual part in the making of these puppets. The colours used to tint and paint the leather are obtained from vegetable and mineral sources. These colours retain their lustre and brightness for a long time. To prevent the puppets from bending a thin strip of smoothened bamboo is fastened vertically along the middle on either side. The arms of the puppet are provided with movable joints. There are puppets for birds, animals, and trees and even for the sea. Puppets of deer and snakes are provided with joints that enable them to bend and move their bodies. In order to find new markets the makers of the leather puppets have used the same techniques to make lampshades in different shapes and sizes. These create striking illumination on being lighted