Pith/Netti/Indian Cork Craft of Karnataka,

Sholapith/ Pith/ Aeschynomene Indica/ Netti is derived from a reed which is pure white in colour and is exposed when the outer layer of the stalk is shaved. The core is light, porous, soft, and pliable and can be shaped to suit the imagination of the artisan. Dextrous hands shape this reed into many objects: scaled down models of temples, churches and mosques, carved images of Durga during puja time in Bengal, marriage headgear, flowers and garlands, toys and mobiles are all crafted from this reed.

Sholapith/ Pith/ Aeschynomene Indica/ Netti is derived from a reed which is pure white in colour and is exposed when the outer layer of the stalk is shaved. The core is light, porous, soft, and pliable and can be shaped to suit the imagination of the artisan. Dextrous hands shape this reed into many objects: scaled down models of temples, churches and mosques, carved images of Durga during puja time in Bengal, marriage headgear, flowers and garlands, toys and mobiles are all crafted from this reed.

PROCESS, TOOLS, AND TECHNIQUE

The pith plant is recognised by the shallow layer of leaves that float on the marshy water at a depth of two to six feet. The pith collector wades into the water to collect this reed, which is then dried thoroughly and sold as sticks in lengths of two to three feet. In Rajamundry district in Andhra Pradesh, for instance rate is Rs. 5 for a stick two feet in size. Good quality pith is pure white and smooth with a soft bark and no nodes, while poor quality pith is one where the core is reddish with a hard bark and has many nodes. The best time for the collection of pith is between the months of December and February.

The tools used are simple and comprise of a knife, scissors, and geometry box. In West Bengal the iron knife called kath, is used to shave the outer cover of the stalk, so that the white core is exposed. This stalk can be shaved further into thin or thick sheets and shaped with a knife or scissors. The parts used to make various figures are glued together. The raw tendrils of the reed are boiled, ground and mixed with flour to make the glue paste. Once the flat sheets are made, a dozen of these can be tied tight at one end and cut into pieces to create various shapes, geometrical and floral. Artisans spend months on a piece, meticulously carving out the details. No part of the pith is wasted and leftover bits are used for making flowers, birds, and animal figures. The colouring on the finished product, if required, is done with bright coloured paint. Artisans from Tamil Nadu even make model townships for use by government officials; their replicas of temples, churches, mosques and buildings of architectural beauty are complete to the smallest detail.

PRACTITIONERS AND LOCATION

Ezhilvighi, a State Awardee and Master Craftswoman from Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, who has been practising this craft for about 17 years says: 'We take special orders from ministers, collectors and other government officials and film actors to make special designs for them. We have even made a wedding card for Vijaykanth, a leading Tamil actor.' J. Jayalalitha, Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu commissioned Ezhilvighi to make a model village, coloured realistically, with all amenities in place.

Ezhilvighi teaches this craft to women in rural areas in Tamil Nadu, so that they use the time productively and earn an income for themselves. She takes about a day for small figures, three days for a medium-sized Taj Mahal and upto 10 days for a big size Ganesha. After the figure is ready, it is enclosed in a glass case for safety and display. She cuts the glass herself and the glass is fixed on a plastic base, on which the figure rests. Her husband makes a yearly purchase of dry pith sticks from Rajamundry in Andhra Pradesh. 'The pith that grows there is of very good quality. They dry it and sell it to us. I buy a stock of 10,000 sticks, at Rs 5 for a 2 feet stick, on a yearly basis.'

In Tamil Nadu the craft flourishes in pockets of Thanjavur, Karaikkal, Tiruchirapalli, Nagapattinam, Pudukottai and in the Union Territory of Pondicherry. Here entire families are engaged in the craft.

In West Bengal, the artisans who craft works of art from the Shola are called Malakars and they claim their descent from Vishwakarma. However in one of the mythological tales of the malakars the origin of shoal crafts and the malakars is ascribed to Lord Shiva. As the legend goes Lord Shiva decided to adorn himself with a pure white mukut /crown and garland at his wedding with Gauri, the daughter of the Himalaya. But Lord Visvakarma, the creator of all craftsmen, did not know what material to use. In exasperation, Shiva threw a lock of hair into the pond. From this sprouted a water plant - the Bhat shoal.

Again Vishwakarma was hesitant, since he said he could carve only hard material such as wood or stone, but could not work with soft, fragile material. This time Shiva plucked a hair from his arm and threw it into the water. There emerged a handsome, young man, who was ordered to make the wedding mukut /crown, mala /garland and ornaments. He was a Malakar. It was thus ordained that at all weddings, the bride and groom should be adorned with shola decorations made by a Malakar. Because of this origin the Malakars do not owe their origin to Vishwakarma, but to Shiva.

Sholapith items form an integral part of the major religious rituals in West Bengal. Fine examples of craftsmanship can be seen during the Durga Puja celebrations. Every community in each village, town, and city needs an image as fine as they can afford, so the craft flourishes there. Traditionally the artisans also craft ritual and decorative items like garlands, chandmalas (literally moon garlands with filigree discs linked into elaborate chains), conical topors, or the head dress worn by young boys during their naming ceremony and by bridegrooms, and the mukut worn by the bride.

According to T. N. Mukherjee in his book Art Manufacturers of India that was compiled for the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1888, pith was worn by the aboriginal tribes as ear ornaments and colourful garlands of pith beads were used to decorate idols and were worn by brides and bridegrooms in Bengal.

On a recent meeting with Sholapith artisans from Dhubri, West Bengal, we noticed some very interesting changes in their craft products, the most amusing of which was the impact of films with Disney's characters, and Steven Spielberg's' Jurassic Park on the people of this little village. The artisan had created a shoal dinosaur, which was as popular among the children of the village, as the traditional magor mach or alligator, one of the toys that are sold all year round both in the village and in bigger towns and cities. Other changes that have taken place over the years are the use of chemical colours instead of the traditional vegetable dyes and the fact that the reed is purchased now instead of being collected by individual craftspersons.

An interesting feature of the sholapith is that it was the material used during British times for the production of the Sola Topi which was a necessary article of headwear for the British as protection from the hot mid-day sun of India. Shola products, when crafted, resemble ivory; however, unlike ivory they are brittle and break easily unless kept carefully. This ephemeral quality of the shoal gives it a precious quality.

Pith/Netti/Indian Cork Craft of Odisha,

Sholapith/ Pith/ Aeschynomene Indica/ Netti is derived from a reed which is pure white in colour and is exposed when the outer layer of the stalk is shaved. The core is light, porous, soft, and pliable and can be shaped to suit the imagination of the artisan. Dextrous hands shape this reed into many objects: scaled down models of temples, churches and mosques, carved images of Durga during puja time in Bengal, marriage headgear, flowers and garlands, toys and mobiles are all crafted from this reed.

Sholapith/ Pith/ Aeschynomene Indica/ Netti is derived from a reed which is pure white in colour and is exposed when the outer layer of the stalk is shaved. The core is light, porous, soft, and pliable and can be shaped to suit the imagination of the artisan. Dextrous hands shape this reed into many objects: scaled down models of temples, churches and mosques, carved images of Durga during puja time in Bengal, marriage headgear, flowers and garlands, toys and mobiles are all crafted from this reed.

PROCESS, TOOLS, AND TECHNIQUE

The pith plant is recognised by the shallow layer of leaves that float on the marshy water at a depth of two to six feet. The pith collector wades into the water to collect this reed, which is then dried thoroughly and sold as sticks in lengths of two to three feet. In Rajamundry district in Andhra Pradesh, for instance rate is Rs. 5 for a stick two feet in size. Good quality pith is pure white and smooth with a soft bark and no nodes, while poor quality pith is one where the core is reddish with a hard bark and has many nodes. The best time for the collection of pith is between the months of December and February.

The tools used are simple and comprise of a knife, scissors, and geometry box. In West Bengal the iron knife called kath, is used to shave the outer cover of the stalk, so that the white core is exposed. This stalk can be shaved further into thin or thick sheets and shaped with a knife or scissors. The parts used to make various figures are glued together. The raw tendrils of the reed are boiled, ground and mixed with flour to make the glue paste. Once the flat sheets are made, a dozen of these can be tied tight at one end and cut into pieces to create various shapes, geometrical and floral. Artisans spend months on a piece, meticulously carving out the details. No part of the pith is wasted and leftover bits are used for making flowers, birds, and animal figures. The colouring on the finished product, if required, is done with bright coloured paint. Artisans from Tamil Nadu even make model townships for use by government officials; their replicas of temples, churches, mosques and buildings of architectural beauty are complete to the smallest detail.

PRACTITIONERS AND LOCATION

Ezhilvighi, a State Awardee and Master Craftswoman from Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, who has been practising this craft for about 17 years says: 'We take special orders from ministers, collectors and other government officials and film actors to make special designs for them. We have even made a wedding card for Vijaykanth, a leading Tamil actor.' J. Jayalalitha, Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu commissioned Ezhilvighi to make a model village, coloured realistically, with all amenities in place.

Ezhilvighi teaches this craft to women in rural areas in Tamil Nadu, so that they use the time productively and earn an income for themselves. She takes about a day for small figures, three days for a medium-sized Taj Mahal and upto 10 days for a big size Ganesha. After the figure is ready, it is enclosed in a glass case for safety and display. She cuts the glass herself and the glass is fixed on a plastic base, on which the figure rests. Her husband makes a yearly purchase of dry pith sticks from Rajamundry in Andhra Pradesh. 'The pith that grows there is of very good quality. They dry it and sell it to us. I buy a stock of 10,000 sticks, at Rs 5 for a 2 feet stick, on a yearly basis.'

In Tamil Nadu the craft flourishes in pockets of Thanjavur, Karaikkal, Tiruchirapalli, Nagapattinam, Pudukottai and in the Union Territory of Pondicherry. Here entire families are engaged in the craft.

In West Bengal, the artisans who craft works of art from the Shola are called Malakars and they claim their descent from Vishwakarma. However in one of the mythological tales of the malakars the origin of shoal crafts and the malakars is ascribed to Lord Shiva. As the legend goes Lord Shiva decided to adorn himself with a pure white mukut /crown and garland at his wedding with Gauri, the daughter of the Himalaya. But Lord Visvakarma, the creator of all craftsmen, did not know what material to use. In exasperation, Shiva threw a lock of hair into the pond. From this sprouted a water plant - the Bhat shoal.

Again Vishwakarma was hesitant, since he said he could carve only hard material such as wood or stone, but could not work with soft, fragile material. This time Shiva plucked a hair from his arm and threw it into the water. There emerged a handsome, young man, who was ordered to make the wedding mukut /crown, mala /garland and ornaments. He was a Malakar. It was thus ordained that at all weddings, the bride and groom should be adorned with shola decorations made by a Malakar. Because of this origin the Malakars do not owe their origin to Vishwakarma, but to Shiva.

Sholapith items form an integral part of the major religious rituals in West Bengal. Fine examples of craftsmanship can be seen during the Durga Puja celebrations. Every community in each village, town, and city needs an image as fine as they can afford, so the craft flourishes there. Traditionally the artisans also craft ritual and decorative items like garlands, chandmalas (literally moon garlands with filigree discs linked into elaborate chains), conical topors, or the head dress worn by young boys during their naming ceremony and by bridegrooms, and the mukut worn by the bride.

According to T. N. Mukherjee in his book Art Manufacturers of India that was compiled for the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1888, pith was worn by the aboriginal tribes as ear ornaments and colourful garlands of pith beads were used to decorate idols and were worn by brides and bridegrooms in Bengal.

On a recent meeting with Sholapith artisans from Dhubri, West Bengal, we noticed some very interesting changes in their craft products, the most amusing of which was the impact of films with Disney's characters, and Steven Spielberg's' Jurassic Park on the people of this little village. The artisan had created a shoal dinosaur, which was as popular among the children of the village, as the traditional magor mach or alligator, one of the toys that are sold all year round both in the village and in bigger towns and cities. Other changes that have taken place over the years are the use of chemical colours instead of the traditional vegetable dyes and the fact that the reed is purchased now instead of being collected by individual craftspersons.

An interesting feature of the sholapith is that it was the material used during British times for the production of the Sola Topi which was a necessary article of headwear for the British as protection from the hot mid-day sun of India. Shola products, when crafted, resemble ivory; however, unlike ivory they are brittle and break easily unless kept carefully. This ephemeral quality of the shoal gives it a precious quality.

Pith/Netti/Indian Cork Craft of Pondicherry,

Sholapith/ Pith/ Aeschynomene Indica/ Netti is derived from a reed which is pure white in colour and is exposed when the outer layer of the stalk is shaved. The core is light, porous, soft, and pliable and can be shaped to suit the imagination of the artisan. Dextrous hands shape this reed into many objects: scaled down models of temples, churches and mosques, carved images of Durga during puja time in Bengal, marriage headgear, flowers and garlands, toys and mobiles are all crafted from this reed.

Sholapith/ Pith/ Aeschynomene Indica/ Netti is derived from a reed which is pure white in colour and is exposed when the outer layer of the stalk is shaved. The core is light, porous, soft, and pliable and can be shaped to suit the imagination of the artisan. Dextrous hands shape this reed into many objects: scaled down models of temples, churches and mosques, carved images of Durga during puja time in Bengal, marriage headgear, flowers and garlands, toys and mobiles are all crafted from this reed.

PROCESS, TOOLS, AND TECHNIQUE

The pith plant is recognised by the shallow layer of leaves that float on the marshy water at a depth of two to six feet. The pith collector wades into the water to collect this reed, which is then dried thoroughly and sold as sticks in lengths of two to three feet. In Rajamundry district in Andhra Pradesh, for instance rate is Rs. 5 for a stick two feet in size. Good quality pith is pure white and smooth with a soft bark and no nodes, while poor quality pith is one where the core is reddish with a hard bark and has many nodes. The best time for the collection of pith is between the months of December and February.

The tools used are simple and comprise of a knife, scissors, and geometry box. In West Bengal the iron knife called kath, is used to shave the outer cover of the stalk, so that the white core is exposed. This stalk can be shaved further into thin or thick sheets and shaped with a knife or scissors. The parts used to make various figures are glued together. The raw tendrils of the reed are boiled, ground and mixed with flour to make the glue paste. Once the flat sheets are made, a dozen of these can be tied tight at one end and cut into pieces to create various shapes, geometrical and floral. Artisans spend months on a piece, meticulously carving out the details. No part of the pith is wasted and leftover bits are used for making flowers, birds, and animal figures. The colouring on the finished product, if required, is done with bright coloured paint. Artisans from Tamil Nadu even make model townships for use by government officials; their replicas of temples, churches, mosques and buildings of architectural beauty are complete to the smallest detail.

PRACTITIONERS AND LOCATION

Ezhilvighi, a State Awardee and Master Craftswoman from Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, who has been practising this craft for about 17 years says: 'We take special orders from ministers, collectors and other government officials and film actors to make special designs for them. We have even made a wedding card for Vijaykanth, a leading Tamil actor.' J. Jayalalitha, Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu commissioned Ezhilvighi to make a model village, coloured realistically, with all amenities in place.

Ezhilvighi teaches this craft to women in rural areas in Tamil Nadu, so that they use the time productively and earn an income for themselves. She takes about a day for small figures, three days for a medium-sized Taj Mahal and upto 10 days for a big size Ganesha. After the figure is ready, it is enclosed in a glass case for safety and display. She cuts the glass herself and the glass is fixed on a plastic base, on which the figure rests. Her husband makes a yearly purchase of dry pith sticks from Rajamundry in Andhra Pradesh. 'The pith that grows there is of very good quality. They dry it and sell it to us. I buy a stock of 10,000 sticks, at Rs 5 for a 2 feet stick, on a yearly basis.'

In Tamil Nadu the craft flourishes in pockets of Thanjavur, Karaikkal, Tiruchirapalli, Nagapattinam, Pudukottai and in the Union Territory of Pondicherry. Here entire families are engaged in the craft.

In West Bengal, the artisans who craft works of art from the Shola are called Malakars and they claim their descent from Vishwakarma. However in one of the mythological tales of the malakars the origin of shoal crafts and the malakars is ascribed to Lord Shiva. As the legend goes Lord Shiva decided to adorn himself with a pure white mukut /crown and garland at his wedding with Gauri, the daughter of the Himalaya. But Lord Visvakarma, the creator of all craftsmen, did not know what material to use. In exasperation, Shiva threw a lock of hair into the pond. From this sprouted a water plant - the Bhat shoal.

Again Vishwakarma was hesitant, since he said he could carve only hard material such as wood or stone, but could not work with soft, fragile material. This time Shiva plucked a hair from his arm and threw it into the water. There emerged a handsome, young man, who was ordered to make the wedding mukut /crown, mala /garland and ornaments. He was a Malakar. It was thus ordained that at all weddings, the bride and groom should be adorned with shola decorations made by a Malakar. Because of this origin the Malakars do not owe their origin to Vishwakarma, but to Shiva.

Sholapith items form an integral part of the major religious rituals in West Bengal. Fine examples of craftsmanship can be seen during the Durga Puja celebrations. Every community in each village, town, and city needs an image as fine as they can afford, so the craft flourishes there. Traditionally the artisans also craft ritual and decorative items like garlands, chandmalas (literally moon garlands with filigree discs linked into elaborate chains), conical topors, or the head dress worn by young boys during their naming ceremony and by bridegrooms, and the mukut worn by the bride.

According to T. N. Mukherjee in his book Art Manufacturers of India that was compiled for the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1888, pith was worn by the aboriginal tribes as ear ornaments and colourful garlands of pith beads were used to decorate idols and were worn by brides and bridegrooms in Bengal.

On a recent meeting with Sholapith artisans from Dhubri, West Bengal, we noticed some very interesting changes in their craft products, the most amusing of which was the impact of films with Disney's characters, and Steven Spielberg's' Jurassic Park on the people of this little village. The artisan had created a shoal dinosaur, which was as popular among the children of the village, as the traditional magor mach or alligator, one of the toys that are sold all year round both in the village and in bigger towns and cities. Other changes that have taken place over the years are the use of chemical colours instead of the traditional vegetable dyes and the fact that the reed is purchased now instead of being collected by individual craftspersons.

An interesting feature of the sholapith is that it was the material used during British times for the production of the Sola Topi which was a necessary article of headwear for the British as protection from the hot mid-day sun of India. Shola products, when crafted, resemble ivory; however, unlike ivory they are brittle and break easily unless kept carefully. This ephemeral quality of the shoal gives it a precious quality.

Pith/Netti/Indian Cork Craft of Tamil Nadu,

Sholapith/ Pith/ Aeschynomene Indica/ Netti is derived from a reed which is pure white in colour and is exposed when the outer layer of the stalk is shaved. The core is light, porous, soft, and pliable and can be shaped to suit the imagination of the artisan. Dextrous hands shape this reed into many objects: scaled down models of temples, churches and mosques, carved images of Durga during puja time in Bengal, marriage headgear, flowers and garlands, toys and mobiles are all crafted from this reed.

Sholapith/ Pith/ Aeschynomene Indica/ Netti is derived from a reed which is pure white in colour and is exposed when the outer layer of the stalk is shaved. The core is light, porous, soft, and pliable and can be shaped to suit the imagination of the artisan. Dextrous hands shape this reed into many objects: scaled down models of temples, churches and mosques, carved images of Durga during puja time in Bengal, marriage headgear, flowers and garlands, toys and mobiles are all crafted from this reed.

PROCESS, TOOLS, AND TECHNIQUE

The pith plant is recognised by the shallow layer of leaves that float on the marshy water at a depth of two to six feet. The pith collector wades into the water to collect this reed, which is then dried thoroughly and sold as sticks in lengths of two to three feet. In Rajamundry district in Andhra Pradesh, for instance rate is Rs. 5 for a stick two feet in size. Good quality pith is pure white and smooth with a soft bark and no nodes, while poor quality pith is one where the core is reddish with a hard bark and has many nodes. The best time for the collection of pith is between the months of December and February.

The tools used are simple and comprise of a knife, scissors, and geometry box. In West Bengal the iron knife called kath, is used to shave the outer cover of the stalk, so that the white core is exposed. This stalk can be shaved further into thin or thick sheets and shaped with a knife or scissors. The parts used to make various figures are glued together. The raw tendrils of the reed are boiled, ground and mixed with flour to make the glue paste. Once the flat sheets are made, a dozen of these can be tied tight at one end and cut into pieces to create various shapes, geometrical and floral. Artisans spend months on a piece, meticulously carving out the details. No part of the pith is wasted and leftover bits are used for making flowers, birds, and animal figures. The colouring on the finished product, if required, is done with bright coloured paint. Artisans from Tamil Nadu even make model townships for use by government officials; their replicas of temples, churches, mosques and buildings of architectural beauty are complete to the smallest detail.

PRACTITIONERS AND LOCATION

Ezhilvighi, a State Awardee and Master Craftswoman from Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, who has been practising this craft for about 17 years says: 'We take special orders from ministers, collectors and other government officials and film actors to make special designs for them. We have even made a wedding card for Vijaykanth, a leading Tamil actor.' J. Jayalalitha, Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu commissioned Ezhilvighi to make a model village, coloured realistically, with all amenities in place.

Ezhilvighi teaches this craft to women in rural areas in Tamil Nadu, so that they use the time productively and earn an income for themselves. She takes about a day for small figures, three days for a medium-sized Taj Mahal and upto 10 days for a big size Ganesha. After the figure is ready, it is enclosed in a glass case for safety and display. She cuts the glass herself and the glass is fixed on a plastic base, on which the figure rests. Her husband makes a yearly purchase of dry pith sticks from Rajamundry in Andhra Pradesh. 'The pith that grows there is of very good quality. They dry it and sell it to us. I buy a stock of 10,000 sticks, at Rs 5 for a 2 feet stick, on a yearly basis.'

In Tamil Nadu the craft flourishes in pockets of Thanjavur, Karaikkal, Tiruchirapalli, Nagapattinam, Pudukottai and in the Union Territory of Pondicherry. Here entire families are engaged in the craft.

In West Bengal, the artisans who craft works of art from the Shola are called Malakars and they claim their descent from Vishwakarma. However in one of the mythological tales of the malakars the origin of shoal crafts and the malakars is ascribed to Lord Shiva. As the legend goes Lord Shiva decided to adorn himself with a pure white mukut /crown and garland at his wedding with Gauri, the daughter of the Himalaya. But Lord Visvakarma, the creator of all craftsmen, did not know what material to use. In exasperation, Shiva threw a lock of hair into the pond. From this sprouted a water plant - the Bhat shoal.

Again Vishwakarma was hesitant, since he said he could carve only hard material such as wood or stone, but could not work with soft, fragile material. This time Shiva plucked a hair from his arm and threw it into the water. There emerged a handsome, young man, who was ordered to make the wedding mukut /crown, mala /garland and ornaments. He was a Malakar. It was thus ordained that at all weddings, the bride and groom should be adorned with shola decorations made by a Malakar. Because of this origin the Malakars do not owe their origin to Vishwakarma, but to Shiva.

Sholapith items form an integral part of the major religious rituals in West Bengal. Fine examples of craftsmanship can be seen during the Durga Puja celebrations. Every community in each village, town, and city needs an image as fine as they can afford, so the craft flourishes there. Traditionally the artisans also craft ritual and decorative items like garlands, chandmalas (literally moon garlands with filigree discs linked into elaborate chains), conical topors, or the head dress worn by young boys during their naming ceremony and by bridegrooms, and the mukut worn by the bride.

According to T. N. Mukherjee in his book Art Manufacturers of India that was compiled for the Glasgow International Exhibition in 1888, pith was worn by the aboriginal tribes as ear ornaments and colourful garlands of pith beads were used to decorate idols and were worn by brides and bridegrooms in Bengal.

On a recent meeting with Sholapith artisans from Dhubri, West Bengal, we noticed some very interesting changes in their craft products, the most amusing of which was the impact of films with Disney's characters, and Steven Spielberg's' Jurassic Park on the people of this little village. The artisan had created a shoal dinosaur, which was as popular among the children of the village, as the traditional magor mach or alligator, one of the toys that are sold all year round both in the village and in bigger towns and cities. Other changes that have taken place over the years are the use of chemical colours instead of the traditional vegetable dyes and the fact that the reed is purchased now instead of being collected by individual craftspersons.

An interesting feature of the sholapith is that it was the material used during British times for the production of the Sola Topi which was a necessary article of headwear for the British as protection from the hot mid-day sun of India. Shola products, when crafted, resemble ivory; however, unlike ivory they are brittle and break easily unless kept carefully. This ephemeral quality of the shoal gives it a precious quality.

Pithora Tribal Art of Chattisgarh,

The craft of tribal paintings in the interiors of Chattisgarh originates from the tradition of creating patterns and designs, both votive and decorative, on floors and walls, as well as in courtyards, to mark occasions - auspicious, religious and celebratory - and cyclical events - both in human life, and the seasonal calendar. As important as the ritualistic aspect of this art is its decorative charm - the mud-plastered or lime-washed homes of the tribals in the interiors of Madhya Pradesh are creatively ornamented with bas relief detailing or with paintings in natural and earthy colours. The red, yellow, black, white and ochre create a striking palette of colours against the mud-brown or lime-white of walls and floors that serve as the canvas. A tribal dwelling with no such relief or painted decoration is unusual; this art is among the core elements in the way of life in these heartland regions.

The craft of tribal paintings in the interiors of Chattisgarh originates from the tradition of creating patterns and designs, both votive and decorative, on floors and walls, as well as in courtyards, to mark occasions - auspicious, religious and celebratory - and cyclical events - both in human life, and the seasonal calendar. As important as the ritualistic aspect of this art is its decorative charm - the mud-plastered or lime-washed homes of the tribals in the interiors of Madhya Pradesh are creatively ornamented with bas relief detailing or with paintings in natural and earthy colours. The red, yellow, black, white and ochre create a striking palette of colours against the mud-brown or lime-white of walls and floors that serve as the canvas. A tribal dwelling with no such relief or painted decoration is unusual; this art is among the core elements in the way of life in these heartland regions.

Pithora Tribal Art of Gujarat,

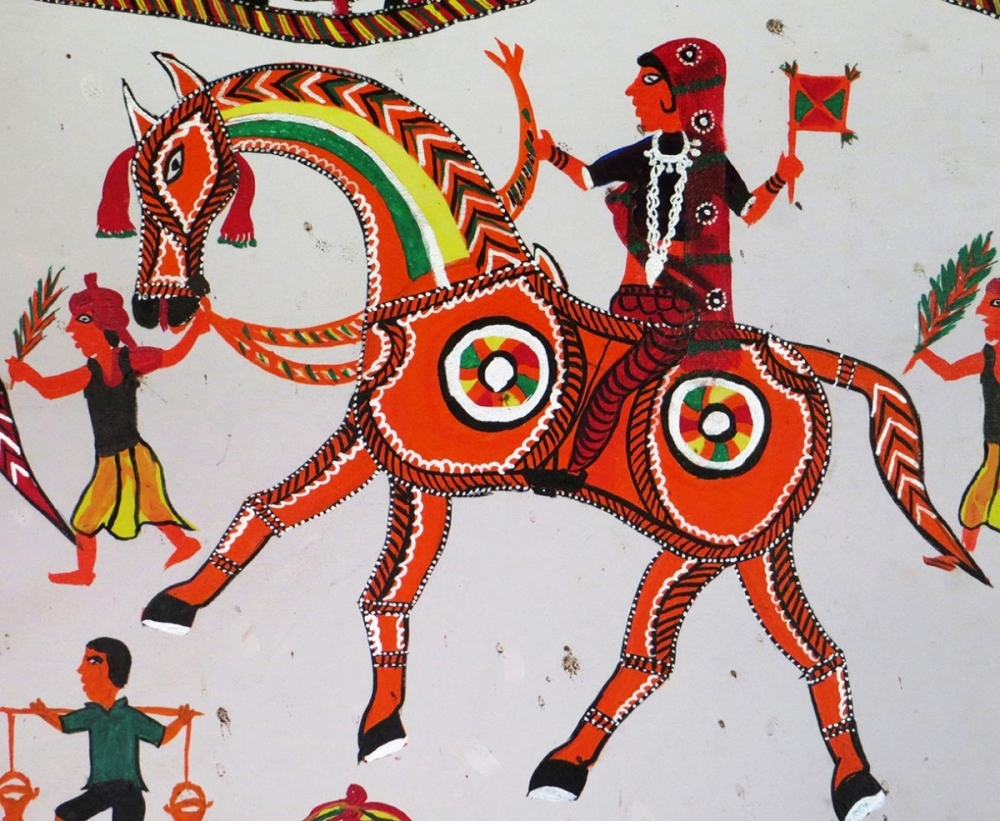

Pithora ritualistic paintings are wall murals, practiced by the Rathwa, Bhil and Nayak tribes of Gujarat. They are found in Panchmahal, Dahod and Chota Udepur. These paintings are usually done by men. They are symbolic of some auspicious occasion in the community such as weddings and childbirth. There is a distinct border pattern within which the painting is executed. The colours are prepared by mixing pigments with milk and liquor [repared from auspicious Mahudo tree. The tools for painting are made from simple elements like bamboo, wood, and cotton. The act of painting on the wall is seen as a ritualistric activity and is accompanied by beating iof the drums, dance, narration in which the entire community participates. It is characterized by the usage of vivid colours and folk iconography. The influences of oral legacy and traditional ar history of the tribal community can be seen coming to life in these wall murals. [gallery ids="176471,176472,176473"]

Pithora ritualistic paintings are wall murals, practiced by the Rathwa, Bhil and Nayak tribes of Gujarat. They are found in Panchmahal, Dahod and Chota Udepur. These paintings are usually done by men. They are symbolic of some auspicious occasion in the community such as weddings and childbirth. There is a distinct border pattern within which the painting is executed. The colours are prepared by mixing pigments with milk and liquor [repared from auspicious Mahudo tree. The tools for painting are made from simple elements like bamboo, wood, and cotton. The act of painting on the wall is seen as a ritualistric activity and is accompanied by beating iof the drums, dance, narration in which the entire community participates. It is characterized by the usage of vivid colours and folk iconography. The influences of oral legacy and traditional ar history of the tribal community can be seen coming to life in these wall murals. [gallery ids="176471,176472,176473"]

Polo Balls of Deulpur, West Bengal,

Deulpur is the only place in the world to supply wooden polo balls to faraway nations of the world. Earlier it was common for them to produce 300,000 polo balls a year of which two third were exported. However, now the market has been taken over by the new plastic polo balls. This change in trend has greatly affected the business of these polo balls. Hence the market has shrunk from the international one to the local one. Deulpur was famous for crafting polo balls out of its dense bamboo groves, as the region has the bamboo roots of the right weight for polo balls which between 100 and 150 grams. To make the polo balls the bamboo root is cut to specific measurement and then chiseled into a ball. This is then filed and then smoothened with sandpaper. The minute gaps are filled with very fine wooden shavings and wax. A homemade white chalk paint is used to pain the ball and the ball is kept in sunlight to dry for two days. These are then finished with some enamel paint. This traditional method is still followed to make polo balls in Deulpur.

Deulpur is the only place in the world to supply wooden polo balls to faraway nations of the world. Earlier it was common for them to produce 300,000 polo balls a year of which two third were exported. However, now the market has been taken over by the new plastic polo balls. This change in trend has greatly affected the business of these polo balls. Hence the market has shrunk from the international one to the local one. Deulpur was famous for crafting polo balls out of its dense bamboo groves, as the region has the bamboo roots of the right weight for polo balls which between 100 and 150 grams. To make the polo balls the bamboo root is cut to specific measurement and then chiseled into a ball. This is then filed and then smoothened with sandpaper. The minute gaps are filled with very fine wooden shavings and wax. A homemade white chalk paint is used to pain the ball and the ball is kept in sunlight to dry for two days. These are then finished with some enamel paint. This traditional method is still followed to make polo balls in Deulpur.

Pooram Festival Crafts of Kerala,

The Thrissur Pooram is a daylong event held at the Vaddakunathan Temple in either the month of April or May that culminates in a procession of richly caparisoned elephants. Essentially, the festival is a contest between two groups representing the chief temples of the city, the Krishna Temple at Thiruvambadi and the Devi Temple at Paramekkavu, with the deity of the host temple acting as witness to the proceedings. Each faction comprises fifteen elephants, each decorated with anklets and a nettipattam, forehead ornament, and carrying three men. Of the three men perched atop the elephants the first holds the koda decorative parasols, the second the Venchamaram whisks of yak wool and the third the circular peacock feather fans aalavattam. The latter two perform in tandem with the rhythm of the chenda or the large drums, alternately holding their respective ritual objects aloft. The central elephant amongst the fifteen from each temple carries the tidambu ceremonial shield and strapped to it is the idol of the temple it represents; the umbrella held is usually of a different colour than those flanking it and more ornate in order to assert the importance of the deity. The temple faction with the most impressive display wins the contest; each temple therefore commissions their festival paraphernalia from a number of different craftsmen in utmost secrecy. The craftsmen are located in Kurmamkulam and Thrissur in Thrissur district. The number and nature of the koda are determined by the temple authority and the generosity of patrons. Traditionally the koda were made of a variety of fabrics ornamented with tassels of dangling pendant like metal elements. The tidambu, a shield like object bearing the image of the deity is held by the priest seated on the chief elephant. The copper embellishments made by the thattan or goldsmiths are stitched onto fabric stretched on the main frame made by a carpenter.. At the foot of the tidambu is an arched form called the prabhamandala in which the idol of the temple deity is affixed for the duration of the procession. Today the repertoire of motifs is far more daring with massive three dimensional sculptures of Theyyam masks, peacocks and images of deities in lightweight material or multi tiered koda fitted to the top of the umbrella. The traditional koda or umbrella embellished with lace, embroidery and metal tassels Nettipattam, a ceremonial forehead ornament worn by elephants. The nettipattam is constructed of embossed copper pieces that are stitched onto a blanket of the desired shape and size. The copper pieces stitched onto the nettipattam, follow a preordained limited design vocabulary; each form has a specific name and position - the snake hood is called the nagapaddam, the crescent is called the chandrakala, the centre piece is called the kumbakinam, the large roundels placed at the top of the nettipattam are called the cattakirmam and the row of roundels that follow it, decreasing in size as the nettipattam tapers towards the bottom, are known as the edakinnam. The edges of the nettipattam are decorated with woolen tassels in white, green, yellow, red, violet and occasionally also in rose and blue.

The Thrissur Pooram is a daylong event held at the Vaddakunathan Temple in either the month of April or May that culminates in a procession of richly caparisoned elephants. Essentially, the festival is a contest between two groups representing the chief temples of the city, the Krishna Temple at Thiruvambadi and the Devi Temple at Paramekkavu, with the deity of the host temple acting as witness to the proceedings. Each faction comprises fifteen elephants, each decorated with anklets and a nettipattam, forehead ornament, and carrying three men. Of the three men perched atop the elephants the first holds the koda decorative parasols, the second the Venchamaram whisks of yak wool and the third the circular peacock feather fans aalavattam. The latter two perform in tandem with the rhythm of the chenda or the large drums, alternately holding their respective ritual objects aloft. The central elephant amongst the fifteen from each temple carries the tidambu ceremonial shield and strapped to it is the idol of the temple it represents; the umbrella held is usually of a different colour than those flanking it and more ornate in order to assert the importance of the deity. The temple faction with the most impressive display wins the contest; each temple therefore commissions their festival paraphernalia from a number of different craftsmen in utmost secrecy. The craftsmen are located in Kurmamkulam and Thrissur in Thrissur district. The number and nature of the koda are determined by the temple authority and the generosity of patrons. Traditionally the koda were made of a variety of fabrics ornamented with tassels of dangling pendant like metal elements. The tidambu, a shield like object bearing the image of the deity is held by the priest seated on the chief elephant. The copper embellishments made by the thattan or goldsmiths are stitched onto fabric stretched on the main frame made by a carpenter.. At the foot of the tidambu is an arched form called the prabhamandala in which the idol of the temple deity is affixed for the duration of the procession. Today the repertoire of motifs is far more daring with massive three dimensional sculptures of Theyyam masks, peacocks and images of deities in lightweight material or multi tiered koda fitted to the top of the umbrella. The traditional koda or umbrella embellished with lace, embroidery and metal tassels Nettipattam, a ceremonial forehead ornament worn by elephants. The nettipattam is constructed of embossed copper pieces that are stitched onto a blanket of the desired shape and size. The copper pieces stitched onto the nettipattam, follow a preordained limited design vocabulary; each form has a specific name and position - the snake hood is called the nagapaddam, the crescent is called the chandrakala, the centre piece is called the kumbakinam, the large roundels placed at the top of the nettipattam are called the cattakirmam and the row of roundels that follow it, decreasing in size as the nettipattam tapers towards the bottom, are known as the edakinnam. The edges of the nettipattam are decorated with woolen tassels in white, green, yellow, red, violet and occasionally also in rose and blue.

Poornakumbham Cotton Sari Weaving of Tamil Nadu,

These are woven following the same technique as the "Ani Butta" saris of Andhra Pradesh. Fine-count cotton saris are woven with Poorna Kumbham/ pot, rudraksha design supported by neuththu (pearl) and cross lines.

These are woven following the same technique as the "Ani Butta" saris of Andhra Pradesh. Fine-count cotton saris are woven with Poorna Kumbham/ pot, rudraksha design supported by neuththu (pearl) and cross lines.

Pottery of Laos,

Laos has a well developed clay and ceramic pottery-making tradition. One finds entire villages dedicated to creating clay objects, using age old methods and traditions with pottery-making as the main source of income for the family. Clay objects created take on both decorative and religious art forms as well as more utilitarian forms. Clay utensils are used both for storage (rice, water, fish, whisky, salt and spices) and cooking and range from simple terracotta, baked in open pits, to the more intricately polished and decorated glazed forms. Traditionally pottery was made by village women, but this has changed and today one finds both men and women participating in the production process.

Laos has a well developed clay and ceramic pottery-making tradition. One finds entire villages dedicated to creating clay objects, using age old methods and traditions with pottery-making as the main source of income for the family. Clay objects created take on both decorative and religious art forms as well as more utilitarian forms. Clay utensils are used both for storage (rice, water, fish, whisky, salt and spices) and cooking and range from simple terracotta, baked in open pits, to the more intricately polished and decorated glazed forms. Traditionally pottery was made by village women, but this has changed and today one finds both men and women participating in the production process.

HISTORY

Excavations at several sites suggest that potters worked their craft as far back as many hundred years ago. Kilns and glazed and unglazed wares have been excavated from construction sites at Ban Pako near Vientiane, Ban Tao Hai (Village of the Jar Kilns) refered to as the Sisattanak Kiln Site, located just out side Vientiane. Some of the pottery has been dated to the Lan Xang period -shards of pottery with a pale, translucent green glaze have been found suggesting that high-quality celadon was produced. Excavations made in 1991 in the vicinity of Ban Xang Hai, on the outskirts of Luang Prabang, have revealed the remains of kilns and fragments of brown glazed jars.

Many legends explain the advent of pottery in the villages. In Ban Chan, three kilometers from Luang Prabang, one legend states that the first clay product to be made was mortar. Not long afterwards, the King of Luang Prabang ordered the villagers to make clay water pipes and big jars for wine and water, for use in the Royal Palace and temples. Soon the villagers became adept at working with clay and it became an additional source of income. The clay can be found near the village. Today, the pottery village of Ban Chan provides souvenirs and décor to Luang Prabang, the world heritage city.

|

PRACTITIONERS

In Laos, one finds pottery producing villages, such as Ban Chan, Ban Thahine in the Luang Prabang, Attapeu and Vientiane provinces. In these villages, age old traditions and methods continue to be used for producing pottery both for local use and commercial markets, and can be openly observed by visitors.

In Laos, pottery was traditionally made by the village women and pottery traditions were passed down orally from mother to daughter for centuries in an unbroken chain. Today whole families work together to produce pots for both local consumption as well as commercial demand.

|

|

MATERIALS AND PROCESSES

Different types of clay are available in Laos and often this is what gives an unglazed pot its colour and appearance. While all villages have their own distinct styles and methods, broadly the steps are as follows:

After the clay is obtained, it is thoroughly checked for stones and other impurities and these are removed before any other processing is done. The clay is then dried in the sun - a process that ensures that no lumps are formed or remain in the clay. Depending on the weather, this could take up to three or four days. The dried clay is then ground and stored or alternatively made into dough and used immediately.

|

|

Lao potters traditionally did not use a wheel to make the desired pots or utensils. Instead clay is pressed into shape using the hands. Layers of dough were added to the original piece and the potter moved around the object, pressing the clay into the desired shape. However, now one increasingly sees the use of the wheel in the pottery villages.

Once a pot is completed it is dried in the shade, so that it does not crack. Leather hard pots are rubbed with a black stone to smoothen the surface, giving it an added shine. The pots are often varnished and put directly in the sun and completely bone dried, making them ready to be fired. Firing is done in an open pit with temperatures going up to 800 degree Celsius. The pots are arranged together and covered with layers of rice straw, which is the set on fire.

|

|

The baked pots are decorated or coloured according to the order placed or the fancy of the potter. Pots are coloured using natural materials like the extract of tamarind seeds or quite often manipulated during the firing process by placing them in proximity to different materials which stain the pots accordingly. Quite often pots are decorated using typical designs - motifs or special marks using rattan or old coins. Originally each village had its own specific designs and motifs but nowadays this distinction no longer holds and different designs are readily available everywhere, although villages still advertise their designs. For example - spiral design, drum design, geometric design.

PRODUCTS

Lao potters today make flower pots, unglazed water pots that keep the water relatively cool, pots for fermented fish and home made whiskey, items for household decoration, religious icons, crockery for cooking and tiles for flooring and roofing. Products are made on order and priced according to their sizes and the intricacy of designs.

Printed Cotton & Silk,

Unlike the drier regions of the Subcontinent, the climatic conditions of Bangladesh did not lend itself to a flourishing tradition of printed textiles. Although some printed fabrics are now being produced in Dhaka, Comilla, and Rajshahi in response to local demands, the best of Bangladesh's textile remains the variety of woven fabrics. Printed cottons, for household use and for garments, are a relatively new phenomenon in Bangladesh. The traditional colours are red, black and yellow prints on a cream or grey background, the motifs chosen are generally floral and leafy. In recent years the design and the colour combinations have become varied and more attractive. The limited availability of silk in Bangladesh has, of necessity, restricted its use. The abiding favourite remains the garod sari with its sophisticated cream background and striking red or green border, edged with an intricate pattern of lines and triangles. Printed silk saris are also being made in a wide selection of colours and patterns, both modern and traditional.

Unlike the drier regions of the Subcontinent, the climatic conditions of Bangladesh did not lend itself to a flourishing tradition of printed textiles. Although some printed fabrics are now being produced in Dhaka, Comilla, and Rajshahi in response to local demands, the best of Bangladesh's textile remains the variety of woven fabrics. Printed cottons, for household use and for garments, are a relatively new phenomenon in Bangladesh. The traditional colours are red, black and yellow prints on a cream or grey background, the motifs chosen are generally floral and leafy. In recent years the design and the colour combinations have become varied and more attractive. The limited availability of silk in Bangladesh has, of necessity, restricted its use. The abiding favourite remains the garod sari with its sophisticated cream background and striking red or green border, edged with an intricate pattern of lines and triangles. Printed silk saris are also being made in a wide selection of colours and patterns, both modern and traditional.

Products of Yak Hair,

The Yak is highly valued and its long, hard outer hair is made into ropes and harnesses, waterproof tents, durable mats and sacks. In former times - long before snow goggles appeared - it was even used for protection against snow-blindness. The commonest eye preservers consist of a gauze netting of closely plaited black yak hair. The soft, down-like inner hair of the yak is woven mainly into soft blankets. Some clothing is made from the hair of the young, two and a half to three year old yak. Yak-hair items are highly regarded by the sherpas as items of trade as well as for use at home and as part of the dowry.

The Yak is highly valued and its long, hard outer hair is made into ropes and harnesses, waterproof tents, durable mats and sacks. In former times - long before snow goggles appeared - it was even used for protection against snow-blindness. The commonest eye preservers consist of a gauze netting of closely plaited black yak hair. The soft, down-like inner hair of the yak is woven mainly into soft blankets. Some clothing is made from the hair of the young, two and a half to three year old yak. Yak-hair items are highly regarded by the sherpas as items of trade as well as for use at home and as part of the dowry.

Puneri Pagadi of Maharashtra,

The Puneri Pagadi is a turban, which is considered a symbol of pride and honour in the city of Pune. It was introduced in the 19th century by Mahadev Govind Ranade, a social reformer. Later, it was worn by many leaders, including Lokmanya Tilak. Though it is a symbol of honour, the pagadi is mostly worn for special occasions like wedding ceremonies and traditional days in schools and colleges. Youngsters wear it while performing the Gondhal art form. In order to preserve its identity, there were demands from the locals to grant the pagadia Geographical Indication (GI) status. Their demand was fulfilled and the pagadi became an intellectual property on 4 September 2009.

The Puneri Pagadi is a turban, which is considered a symbol of pride and honour in the city of Pune. It was introduced in the 19th century by Mahadev Govind Ranade, a social reformer. Later, it was worn by many leaders, including Lokmanya Tilak. Though it is a symbol of honour, the pagadi is mostly worn for special occasions like wedding ceremonies and traditional days in schools and colleges. Youngsters wear it while performing the Gondhal art form. In order to preserve its identity, there were demands from the locals to grant the pagadia Geographical Indication (GI) status. Their demand was fulfilled and the pagadi became an intellectual property on 4 September 2009.

Punja Dhurrie Weaving of Rajasthan,

Panja dhurrie weaving is a widely practiced craft in Rajasthan. Items sucha s large floor coverings, cart enclosures, animal cover for winters and cloth for large sacks are produced under this craft-form. Tools such as bristle brush, temple to maintain width, horizontal floor loom, needle, scissor, knife are used for the crafting process.

Panja dhurrie weaving is a widely practiced craft in Rajasthan. Items sucha s large floor coverings, cart enclosures, animal cover for winters and cloth for large sacks are produced under this craft-form. Tools such as bristle brush, temple to maintain width, horizontal floor loom, needle, scissor, knife are used for the crafting process.

Puppets of Nepal,

Puppets, based on the masked dancers of the jatras (ceremonial, ritualistic, and religious processions/occasions), manipulated with cords are crafted and sold all over Kathmandu Valley. They are often multi-armed deities holding miniature wooden weapons in each hand. This new craft was introduced into Katmandu only a few decades back by a German lady. The puppet heads, like the masks they emulate, are made of clay or papier mache. Colourfully and ethnically dressed, they are a popular tourist and export item.

Puppets, based on the masked dancers of the jatras (ceremonial, ritualistic, and religious processions/occasions), manipulated with cords are crafted and sold all over Kathmandu Valley. They are often multi-armed deities holding miniature wooden weapons in each hand. This new craft was introduced into Katmandu only a few decades back by a German lady. The puppet heads, like the masks they emulate, are made of clay or papier mache. Colourfully and ethnically dressed, they are a popular tourist and export item.

Puppets of Rajasthan,

The marionettes of Rajasthan are known as kathputhlis or string puppets. The community that makes them and performs with them are the bhatts who wander from village to village with their puppet show during the dry season when cultivation is not possible. The puppets are small in size --- about two feet in height. They are stylized, and have a wooden head and large eyes. The rest of the body is made of cloth and stuffed rags. The wood used for the head is mango wood or akada root. The cloth used for the body is soft and light to allow for free movement. The kathputhlis have highly exaggerated immobile features with enormous noses and wide eyes. Unless they are horse riders, the puppets have no legs. They are covered with a long pleated skirt. The puppet has a long string for the head which reaches the manipulator and then joins the waist; the strings from the two hands of the puppet are joined in the hands of the manipulator. The costumes are regional and traditional. The themes are Rajasthani historical tales or local legends. A few characters and items like the court dancer, stunt horse rider, and snake charmer, are a must. The main centers where the puppets are made are Jaipur and Jodhpur.

The marionettes of Rajasthan are known as kathputhlis or string puppets. The community that makes them and performs with them are the bhatts who wander from village to village with their puppet show during the dry season when cultivation is not possible. The puppets are small in size --- about two feet in height. They are stylized, and have a wooden head and large eyes. The rest of the body is made of cloth and stuffed rags. The wood used for the head is mango wood or akada root. The cloth used for the body is soft and light to allow for free movement. The kathputhlis have highly exaggerated immobile features with enormous noses and wide eyes. Unless they are horse riders, the puppets have no legs. They are covered with a long pleated skirt. The puppet has a long string for the head which reaches the manipulator and then joins the waist; the strings from the two hands of the puppet are joined in the hands of the manipulator. The costumes are regional and traditional. The themes are Rajasthani historical tales or local legends. A few characters and items like the court dancer, stunt horse rider, and snake charmer, are a must. The main centers where the puppets are made are Jaipur and Jodhpur.