Minakari/Enamelling on Jewellery and Jewelled Objects of Rajasthan,

Enamelling or minakari can be described as the art of colouring and ornamenting the surface of metals by fusing over it brilliant colours that are patterned in an intricate design. Enamel or minawork was a notable Mughal innovation in metalcraft. Mina was popular both with the Mughals and the Hindu princes of Rajasthan where it was used for enriching jewellery and for creating other precious objects. Using a variety of colours the craftspersons ornament the surface of the metal. Gold has traditionally been used for minakari jewellery as its lustre brings out the colours of the enamels; it also holds the enamel better and lasts longer. Silver is a later introduction and is used for artefacts like boxes, bowls, spoons, and art pieces. Copper, which is used for handicraft products, was introduced only after the Gold Control Act --- which compelled the minakars to look for a material other than gold --- was enforced in India. The work of the minakar often went unnoticed as, traditionally, minakari patterns were used basically as a backing for the famous kundan or stone-studded jewellery. Several reasons were cited to explain this: the prosaic explanation was that it allowed the wearer to reverse the jewellery, while the more poetic reason was that the wearer of the jewellery was promised a special joy in the secret of the hidden design! The minakars belong to the Sonar or Soni caste of kshatriyas and identify themselves with the name of Minakar or Verma. This is a hereditary craft and the minakars seldom allow outsiders to acquire any knowledge of their craft. The process followed is long and complex and a single piece of mina can pass through many hands before it is completed. The traditional sequence starts with the designer (nacquash, chitera), and moves on to the goldsmith (sonar, swarnakar), the engraver who engraves the design (kalamkar, khodnakar), the enamellist who applies the colour (minakar), the polisher (ghotnawala, chiknawala), the stone-setter (jadia, kundansaaz), and the stringer (patua), all of whom are part of the chain that creates the finished product. However, often a single artisan performs a multiplicity of tasks. Like a miniature artist, the minakar engraves the surface of the metal with intricate designs using a metal stylus. This is then filled in with colours. When placed in a furnace, the colours fuse and harden to become one with the surface. The piece is then gently rubbed with a file and cleaned with a mixture of lemon and tamarind, which helps emphasise the brilliance of each colour. Enamel colours are metal oxides mixed with a frit of finely powdered glass; the shade obtained varies according to the amount of oxide added and the powder is suspended in water for ease of application. The colour yellow is obtained through the use of chromate of potash, violet through carbonate of manganese, blue through cobalt oxide, green through copper oxide, brown through red oxide, and black through manganese, iron, and cobalt. The brilliant red is the most difficult of colours to achieve. White and ivory, also difficult, are achieved through a mix of antinomies of potash, hydrated iron oxide, and carbonate of zinc. The minakar applies the colour according to their level of hardness, beginning with the hardest. Before the enamel is applied the surface of the ornament is carefully cleaned. In their raw form these mixtures do not always show their true colours, which emerge only when they are fired in the kiln. The average firing temperature is about 850 degrees celsius. The enamel colours are bought either from Amritsar in Punjab or from Germany or France. Enamelling was earlier practised in many centres in India, with each region specialising in its own variation of style and technique. In Lucknow the speciality of the minakars was blue and green enamelling on silver, while in Banaras the dusky rose-pink or the gulabi mina was the dominant colour. The craft was also practised in Kangra, Kashmir, and Bhawalpur. It was, however, most vibrant in Jaipur (Rajasthan) and in Delhi, and these two centres continue to create minakari pieces of excellence till today. The family members of Ram Krishan Minakar, a master craftsman and a National Award winner state that the craft of minakari has been handed down for at least four generations, if not longer. The children, too, are interested in following the family tradition. Ram Krishan's family today works with a copper and brass alloy to make handicraft items that are sold all over the country and even exported. They are one of the few minakar families who work with this alloy. They traditionally worked with gold till the Gold Control Act was introduced in India. The mix of the alloy is a closely guarded family secret. In Delhi and Jaipur two forms of enamelling are popular: the champlevé style where the metal is engraved to create depressions into which colour is embedded; and the repoussé form in which a thin metal plate is embossed over a prefabricated die. This die has the design etched on one of its sides. The metal plate is moulded over the die by stamping on it. Once this is done the grooves are etched with the help of a metal stylus and the colours filled into the areas created. A metal stylus with its front flattened and shaped like a wedge is used for carving and engraving the base metal. The mina is powdered before use with a grinder and is dispersed with a metal spatula into the palette. Long pointed needles of different thicknesses are used for applying the colour on the carved or moulded metal plate. Blocks are used both for engraving and for embossing the metal plate. The kiln is an essential part of the process and can range from a relatively modern to a homemade one. Tools for the final cleaning of the piece include an iron needle and a file. The design vocabulary in minakari is vast and includes many patterns. Creepers and vines, flowers (particularly the lotus), birds (especially the parrot and the peacock), paisleys, geometric patterns, and calligraphy are some of the more commonly used designs. The colours used are red, green, white, and blue. In its contemporary form, minakari is not confined to traditional jewellery but ranges into more 'modern' products, often with a copper base, including bowls, ashtrays, key chains, vases, spoons, figures of deities, and wall pieces.

Enamelling or minakari can be described as the art of colouring and ornamenting the surface of metals by fusing over it brilliant colours that are patterned in an intricate design. Enamel or minawork was a notable Mughal innovation in metalcraft. Mina was popular both with the Mughals and the Hindu princes of Rajasthan where it was used for enriching jewellery and for creating other precious objects. Using a variety of colours the craftspersons ornament the surface of the metal. Gold has traditionally been used for minakari jewellery as its lustre brings out the colours of the enamels; it also holds the enamel better and lasts longer. Silver is a later introduction and is used for artefacts like boxes, bowls, spoons, and art pieces. Copper, which is used for handicraft products, was introduced only after the Gold Control Act --- which compelled the minakars to look for a material other than gold --- was enforced in India. The work of the minakar often went unnoticed as, traditionally, minakari patterns were used basically as a backing for the famous kundan or stone-studded jewellery. Several reasons were cited to explain this: the prosaic explanation was that it allowed the wearer to reverse the jewellery, while the more poetic reason was that the wearer of the jewellery was promised a special joy in the secret of the hidden design! The minakars belong to the Sonar or Soni caste of kshatriyas and identify themselves with the name of Minakar or Verma. This is a hereditary craft and the minakars seldom allow outsiders to acquire any knowledge of their craft. The process followed is long and complex and a single piece of mina can pass through many hands before it is completed. The traditional sequence starts with the designer (nacquash, chitera), and moves on to the goldsmith (sonar, swarnakar), the engraver who engraves the design (kalamkar, khodnakar), the enamellist who applies the colour (minakar), the polisher (ghotnawala, chiknawala), the stone-setter (jadia, kundansaaz), and the stringer (patua), all of whom are part of the chain that creates the finished product. However, often a single artisan performs a multiplicity of tasks. Like a miniature artist, the minakar engraves the surface of the metal with intricate designs using a metal stylus. This is then filled in with colours. When placed in a furnace, the colours fuse and harden to become one with the surface. The piece is then gently rubbed with a file and cleaned with a mixture of lemon and tamarind, which helps emphasise the brilliance of each colour. Enamel colours are metal oxides mixed with a frit of finely powdered glass; the shade obtained varies according to the amount of oxide added and the powder is suspended in water for ease of application. The colour yellow is obtained through the use of chromate of potash, violet through carbonate of manganese, blue through cobalt oxide, green through copper oxide, brown through red oxide, and black through manganese, iron, and cobalt. The brilliant red is the most difficult of colours to achieve. White and ivory, also difficult, are achieved through a mix of antinomies of potash, hydrated iron oxide, and carbonate of zinc. The minakar applies the colour according to their level of hardness, beginning with the hardest. Before the enamel is applied the surface of the ornament is carefully cleaned. In their raw form these mixtures do not always show their true colours, which emerge only when they are fired in the kiln. The average firing temperature is about 850 degrees celsius. The enamel colours are bought either from Amritsar in Punjab or from Germany or France. Enamelling was earlier practised in many centres in India, with each region specialising in its own variation of style and technique. In Lucknow the speciality of the minakars was blue and green enamelling on silver, while in Banaras the dusky rose-pink or the gulabi mina was the dominant colour. The craft was also practised in Kangra, Kashmir, and Bhawalpur. It was, however, most vibrant in Jaipur (Rajasthan) and in Delhi, and these two centres continue to create minakari pieces of excellence till today. The family members of Ram Krishan Minakar, a master craftsman and a National Award winner state that the craft of minakari has been handed down for at least four generations, if not longer. The children, too, are interested in following the family tradition. Ram Krishan's family today works with a copper and brass alloy to make handicraft items that are sold all over the country and even exported. They are one of the few minakar families who work with this alloy. They traditionally worked with gold till the Gold Control Act was introduced in India. The mix of the alloy is a closely guarded family secret. In Delhi and Jaipur two forms of enamelling are popular: the champlevé style where the metal is engraved to create depressions into which colour is embedded; and the repoussé form in which a thin metal plate is embossed over a prefabricated die. This die has the design etched on one of its sides. The metal plate is moulded over the die by stamping on it. Once this is done the grooves are etched with the help of a metal stylus and the colours filled into the areas created. A metal stylus with its front flattened and shaped like a wedge is used for carving and engraving the base metal. The mina is powdered before use with a grinder and is dispersed with a metal spatula into the palette. Long pointed needles of different thicknesses are used for applying the colour on the carved or moulded metal plate. Blocks are used both for engraving and for embossing the metal plate. The kiln is an essential part of the process and can range from a relatively modern to a homemade one. Tools for the final cleaning of the piece include an iron needle and a file. The design vocabulary in minakari is vast and includes many patterns. Creepers and vines, flowers (particularly the lotus), birds (especially the parrot and the peacock), paisleys, geometric patterns, and calligraphy are some of the more commonly used designs. The colours used are red, green, white, and blue. In its contemporary form, minakari is not confined to traditional jewellery but ranges into more 'modern' products, often with a copper base, including bowls, ashtrays, key chains, vases, spoons, figures of deities, and wall pieces.

Miniature Painting of Andhra Pradesh,

This is a traditional craft of Andhra Pradesh --- found usually on sliced ivory pieces ---that has been practised from Mughal times onwards and was mainly. Intricate and fascinating details of Mughal culture are depicted. Miniatures are also painted on trinket boxes made of teak with sandalwood mounts and on silver filigree boxes; pendants and cuff links often have miniatures on them. These products are in high demand in the export market.

This is a traditional craft of Andhra Pradesh --- found usually on sliced ivory pieces ---that has been practised from Mughal times onwards and was mainly. Intricate and fascinating details of Mughal culture are depicted. Miniatures are also painted on trinket boxes made of teak with sandalwood mounts and on silver filigree boxes; pendants and cuff links often have miniatures on them. These products are in high demand in the export market.

Miniature Painting of Chamba, Himachal Pradesh,

With the disintegration of patronage to paintings in the Mughal Court of Aurangzeb artists moved to wider fields of patronage; with further migrations in number after the fall of Delhi in 1739 to the Persian ruler Nadir Shah. This thus initiated the development of the Pahari - Hill style - the Pahari kalam school of miniature art. The princely Himalayan hill state kingdoms of Nurpur, Chamba, Basohli, Guler, Kangra, Mandi, Kullu and Bilaspur provided the patronage. In keeping with their patrons demands the themes of Pahari miniatures had strong religious and spiritual undertones and included scenes from the Hindu epics of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, the Gita Govinda , the Bhagvata Purana, episodes from the lives of Radha and God Krishna.Tales and legends were also painted all contextualized within the Pahari landscape using mineral or stone colours and painted on handmade paper, the paintings on completion were burnished by rubbing the back with an agate stone. The tools and styles remain similar till today.

With the disintegration of patronage to paintings in the Mughal Court of Aurangzeb artists moved to wider fields of patronage; with further migrations in number after the fall of Delhi in 1739 to the Persian ruler Nadir Shah. This thus initiated the development of the Pahari - Hill style - the Pahari kalam school of miniature art. The princely Himalayan hill state kingdoms of Nurpur, Chamba, Basohli, Guler, Kangra, Mandi, Kullu and Bilaspur provided the patronage. In keeping with their patrons demands the themes of Pahari miniatures had strong religious and spiritual undertones and included scenes from the Hindu epics of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, the Gita Govinda , the Bhagvata Purana, episodes from the lives of Radha and God Krishna.Tales and legends were also painted all contextualized within the Pahari landscape using mineral or stone colours and painted on handmade paper, the paintings on completion were burnished by rubbing the back with an agate stone. The tools and styles remain similar till today.

Miniature Painting of Rajasthan,

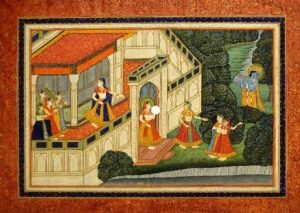

There is an enormous Mughal influence on the traditional heritage of Rajasthan. The miniature paintings that were crafted, depict royal courts, palace proceedings and hunting performances in the midst of the natural environment. The artists used to accompany the rulers on their military expeditions to record their prowess. During this time, royal portraits of the rulers were also commissioned. Following the Mughal period, many paintings had themes depicting Krishna Rasleela, Krishna with gopis were made. Bright and vibrant, naturally obtained colours were used. Gold and Silver was heavily used in order to depict the metallic work done on the architecture of the Mughal times. The most common fabric for miniature paintings was silk, followed by cotton. Brushes were made of squirrel hair. Colors were extracted from different stones by the process of crushing and grinding. It was later mixed with gond (adhesive) to convert it into a liquid form. Miniature paintings have been in existence in Rajasthan for centuries. The various schools of painting in Rajasthan are: Kangra School: The materials used are real gold, stone, and water colours which are then painted on old handmade paper. The outline of the subject is drawn with a pencil. Separate colours are filled in and the painting is rubbed on glass. Shading is done later. The last step is face decoration. Gilheri or squirrel-hair brushes are used for painting and real gold and silver are used to impart the glittering look to the painting. These paintings developed under the patronage of various rulers; presently Jaipur is an important centre Jodhpur School: Here also real gold and stone colours are used on old handmade paper, with love scenes being the most common motifs. Mughal School of Painting: Real gold and stone colours are used to paint on silk. Love scenes and the Mughal durbar are depicted. Nowadays these paintings are also done on wood and marble stones. Jaipur School: These depict the portraits of kings, durbars, and gods and goddesses on old handmade papers with real gold and stone colours. Mewar School of Painting: These depict hunting scenes which are shown on cloth and handmade paper in stone and stone colours.

There is an enormous Mughal influence on the traditional heritage of Rajasthan. The miniature paintings that were crafted, depict royal courts, palace proceedings and hunting performances in the midst of the natural environment. The artists used to accompany the rulers on their military expeditions to record their prowess. During this time, royal portraits of the rulers were also commissioned. Following the Mughal period, many paintings had themes depicting Krishna Rasleela, Krishna with gopis were made. Bright and vibrant, naturally obtained colours were used. Gold and Silver was heavily used in order to depict the metallic work done on the architecture of the Mughal times. The most common fabric for miniature paintings was silk, followed by cotton. Brushes were made of squirrel hair. Colors were extracted from different stones by the process of crushing and grinding. It was later mixed with gond (adhesive) to convert it into a liquid form. Miniature paintings have been in existence in Rajasthan for centuries. The various schools of painting in Rajasthan are: Kangra School: The materials used are real gold, stone, and water colours which are then painted on old handmade paper. The outline of the subject is drawn with a pencil. Separate colours are filled in and the painting is rubbed on glass. Shading is done later. The last step is face decoration. Gilheri or squirrel-hair brushes are used for painting and real gold and silver are used to impart the glittering look to the painting. These paintings developed under the patronage of various rulers; presently Jaipur is an important centre Jodhpur School: Here also real gold and stone colours are used on old handmade paper, with love scenes being the most common motifs. Mughal School of Painting: Real gold and stone colours are used to paint on silk. Love scenes and the Mughal durbar are depicted. Nowadays these paintings are also done on wood and marble stones. Jaipur School: These depict the portraits of kings, durbars, and gods and goddesses on old handmade papers with real gold and stone colours. Mewar School of Painting: These depict hunting scenes which are shown on cloth and handmade paper in stone and stone colours.

Miniature Painting on Wood of Rajasthan,

A hybrid of miniature traditions of Rajasthan is executed directly onto wooden objects by the local artisans to create spectacular furniture and wooden items. The production cluster is centered around Kishangarh. Objects such as miniatures on paper as well as cloth, tables, sofas, chairs, swings and vases are decorated with miniature art work using brushes.

A hybrid of miniature traditions of Rajasthan is executed directly onto wooden objects by the local artisans to create spectacular furniture and wooden items. The production cluster is centered around Kishangarh. Objects such as miniatures on paper as well as cloth, tables, sofas, chairs, swings and vases are decorated with miniature art work using brushes.

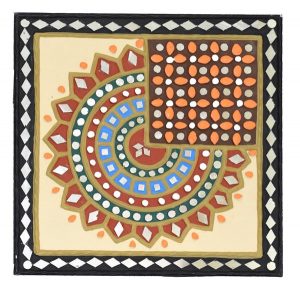

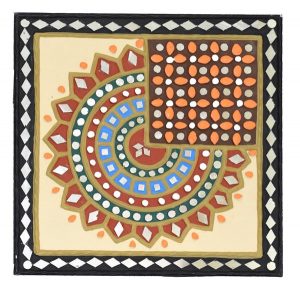

Mirror Decorations on Plaster and Lac,

In several parts of Pakistan mirror pieces are used to create decorative patterns on objects made of plaster and lac. Mirrors of the same size or different sizes, both convex and flat, are arranged in geometrical and floral patterns. They can be found as decorations on wall and small objects, such as surahis, animal figures, jewellery boxes, rehals, etc. Wall decorations can be seen in the Shish Mahal in the Lahore Fort.

In several parts of Pakistan mirror pieces are used to create decorative patterns on objects made of plaster and lac. Mirrors of the same size or different sizes, both convex and flat, are arranged in geometrical and floral patterns. They can be found as decorations on wall and small objects, such as surahis, animal figures, jewellery boxes, rehals, etc. Wall decorations can be seen in the Shish Mahal in the Lahore Fort.

Mirror Work and Embroidery of Rajasthan,

The women in Sikar and Jhunjhuna embroider animal, bird, and tree motifs on their skirt borders. The women of Bikaner embroider their thick red woollen shawls with a running stitch, in a bandhini design which has the same pattern on both the sides. The Meos of Alwar use a chain stitch in contrasting colours along with the phulkari bagh stitch. The main colours are yellow, black, and white. The motifs are geometrical and floral. Jaisalmer is a very important embroidery centre using almost all varieties of stitches along with mirrors. Quilts called rallis are appliquéd with geometrically shaped pieces of cloth in dark, earthy colours. The embroidery done on silk is replicated on leather which is found locally. Shoes are covered with thread embroidery in brilliant colours; for urban markets the colours are toned down and a lot of gold thread is used. Camel and horse saddles are decorated with appliqué and embroidery done with a hook. The pichwai of Nathdwara, is an embroidered cloth-hanging used as a decoration in temples and temple-chariots. The temple of Srinathji has made this cloth-hanging very sacred, both as an offering at the temple and as a souvenir to take home. The outlines of the pichwai are dark and it is patterned with colourful embroidery; gold thread is used in some to highlight the design. When the pichwai is appliquéd, the background is in red cotton while the stitches are in cream, green, yellow, and black; white is used for the outlines. Gota work is done on velvet and are on appliquéd wall scrolls.

The women in Sikar and Jhunjhuna embroider animal, bird, and tree motifs on their skirt borders. The women of Bikaner embroider their thick red woollen shawls with a running stitch, in a bandhini design which has the same pattern on both the sides. The Meos of Alwar use a chain stitch in contrasting colours along with the phulkari bagh stitch. The main colours are yellow, black, and white. The motifs are geometrical and floral. Jaisalmer is a very important embroidery centre using almost all varieties of stitches along with mirrors. Quilts called rallis are appliquéd with geometrically shaped pieces of cloth in dark, earthy colours. The embroidery done on silk is replicated on leather which is found locally. Shoes are covered with thread embroidery in brilliant colours; for urban markets the colours are toned down and a lot of gold thread is used. Camel and horse saddles are decorated with appliqué and embroidery done with a hook. The pichwai of Nathdwara, is an embroidered cloth-hanging used as a decoration in temples and temple-chariots. The temple of Srinathji has made this cloth-hanging very sacred, both as an offering at the temple and as a souvenir to take home. The outlines of the pichwai are dark and it is patterned with colourful embroidery; gold thread is used in some to highlight the design. When the pichwai is appliquéd, the background is in red cotton while the stitches are in cream, green, yellow, and black; white is used for the outlines. Gota work is done on velvet and are on appliquéd wall scrolls.

Mithila Folk Painting of Madhubani, Bihar,

Madhuban, in the Himalayan foothills of Mithila, is the home of the Madhubani paintings. Traditionally, on festive and religious occasions, and during social celebrations, the women of Mithila decorated their homes and courtyards with images that were vibrant, colourful, and deeply religious. The subjects of these paintings were gods and goddesses, mythology and nature. The women use rich earthy colours --- reds, yellows, indigoes, and blues --- in their lyrical paintings of gods and goddesses like Rama-Sita, Krishna-Radha, and Shiva-Gauri. These were intended for shrines and in the khovar, the innermost chamber of the house where the bride and bridegroom began their married lives. The women used basic materials like gum, thread, and matchsticks or fine bamboo slivers wrapped in cotton to execute these wonderfully eloquent paintings. The women passed on this traditional art form to their daughters over generations and this art is still alive and thriving. During a severe drought in the 1960s in the normally fertile region of Mithila, the people of Mithila were forced to look at something other than agriculture as a source of income. They got the women of Mithila to execute their art on paper and cloth, and today Madhubani is one of the most popular works of folk art all over the world. The themes and techniques used for the painting are still the same. The canvas has changed from walls and floors to cloth and paper and papier mache. On auspicious occasions, and at festivals, marriages, and births, women paint aripan and dhuli chitras or dust paintings on the mud floors of their huts. Geometrical and highly stylised, these paintings are open astrological charts, a storehouse of the wisdom of the ages. Folk paintings are done by a community of tribesmen called the chitrakars, in the Santhal Parganas,. They paint scrolls in the traditional manner, depicting stories and moral lessons. They carry the scroll paintings from one Santhal village to another and sing the story, for which they receive some remuneration.

Madhuban, in the Himalayan foothills of Mithila, is the home of the Madhubani paintings. Traditionally, on festive and religious occasions, and during social celebrations, the women of Mithila decorated their homes and courtyards with images that were vibrant, colourful, and deeply religious. The subjects of these paintings were gods and goddesses, mythology and nature. The women use rich earthy colours --- reds, yellows, indigoes, and blues --- in their lyrical paintings of gods and goddesses like Rama-Sita, Krishna-Radha, and Shiva-Gauri. These were intended for shrines and in the khovar, the innermost chamber of the house where the bride and bridegroom began their married lives. The women used basic materials like gum, thread, and matchsticks or fine bamboo slivers wrapped in cotton to execute these wonderfully eloquent paintings. The women passed on this traditional art form to their daughters over generations and this art is still alive and thriving. During a severe drought in the 1960s in the normally fertile region of Mithila, the people of Mithila were forced to look at something other than agriculture as a source of income. They got the women of Mithila to execute their art on paper and cloth, and today Madhubani is one of the most popular works of folk art all over the world. The themes and techniques used for the painting are still the same. The canvas has changed from walls and floors to cloth and paper and papier mache. On auspicious occasions, and at festivals, marriages, and births, women paint aripan and dhuli chitras or dust paintings on the mud floors of their huts. Geometrical and highly stylised, these paintings are open astrological charts, a storehouse of the wisdom of the ages. Folk paintings are done by a community of tribesmen called the chitrakars, in the Santhal Parganas,. They paint scrolls in the traditional manner, depicting stories and moral lessons. They carry the scroll paintings from one Santhal village to another and sing the story, for which they receive some remuneration.

Mizo Puanchei of Mizoram,

Mizo Puanchei is a kind of shawl which is draped around the waist by tucking the opposite ends onto the side. The word Puan is referred to a shawl like cloth fabric that is woven by hand. The Mizo Punachei is considered to be an essential customary wear for women from Mizoram during auspicious rituals and ceremonies. An important component of the Mizo marriage outfit it is also draped on other festive occasions celebrated by the community. The Puan is made on a loin loom by women weavers. The ground fabric is a warp faced plain weave which is made using different yarns. Unlike other kinds of Puans the Mizo Puanchei involves sewing three pieces of cloth together. Many traditional designs and colors are incorporated and inscribed on these unique shawls which enhance their aesthetic appearance. The most common motifs designed are, disul and halkha which run along the bands in contrasting colors.

Mizo Puanchei is a kind of shawl which is draped around the waist by tucking the opposite ends onto the side. The word Puan is referred to a shawl like cloth fabric that is woven by hand. The Mizo Punachei is considered to be an essential customary wear for women from Mizoram during auspicious rituals and ceremonies. An important component of the Mizo marriage outfit it is also draped on other festive occasions celebrated by the community. The Puan is made on a loin loom by women weavers. The ground fabric is a warp faced plain weave which is made using different yarns. Unlike other kinds of Puans the Mizo Puanchei involves sewing three pieces of cloth together. Many traditional designs and colors are incorporated and inscribed on these unique shawls which enhance their aesthetic appearance. The most common motifs designed are, disul and halkha which run along the bands in contrasting colors.

Moirang Phee of Manipur,

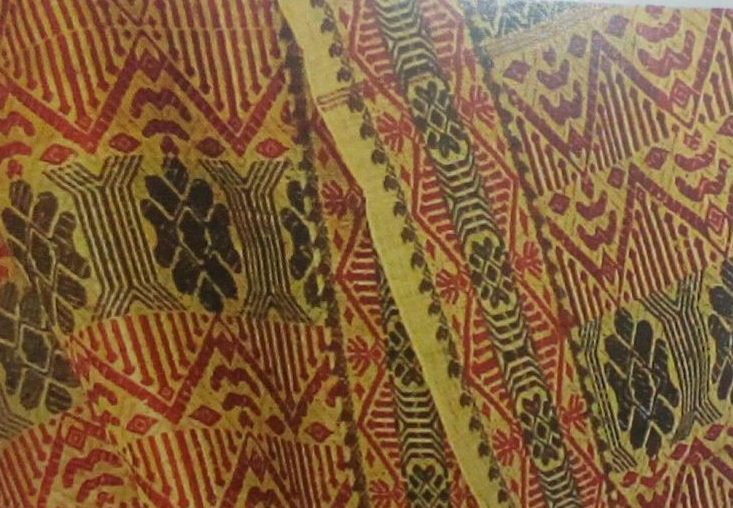

The Moirang Phee is a traditional fabric which has a specific design called the "moirang pheejin". The design is woven sequentially on the edges of both lengths of the fabric and oriented towards the centre. Cotton or silk threads are used. It was originally a product of Moirang village. The fabric is woven by women, and is used by them during marriages and other festivities. The design, known in the local language as “yarongphi” (“ya”:tooth, “rong”:long, “phee”:cloth), is woven in the extra weft technique. The triangular motifs, arranged in varying steps, on the longitudinal borders of the fabric, have sharp edges at the top.

The Moirang Phee is a traditional fabric which has a specific design called the "moirang pheejin". The design is woven sequentially on the edges of both lengths of the fabric and oriented towards the centre. Cotton or silk threads are used. It was originally a product of Moirang village. The fabric is woven by women, and is used by them during marriages and other festivities. The design, known in the local language as “yarongphi” (“ya”:tooth, “rong”:long, “phee”:cloth), is woven in the extra weft technique. The triangular motifs, arranged in varying steps, on the longitudinal borders of the fabric, have sharp edges at the top.

Molakalmuru Sari Weaving of Karnataka,

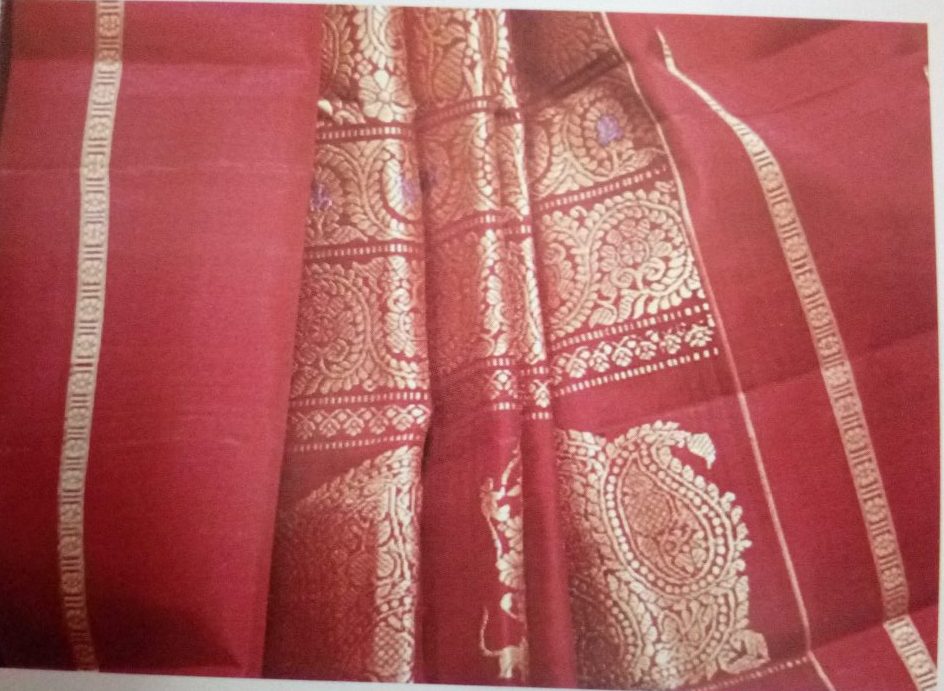

Molakalmuru is a traditional saree from Karnataka state. The raw materials used to weave this saree are mulberry filature silk for the warp and charkha silk for the weft. The weaving is done mainly on pit looms with either the fly shuttle or throw shuttle technique. Three shuttles are used: one shuttle for body portion and two shuttles for both the borders. Molakalmuru silks are distinguished from their sister silk weaving traditions in Mysore and Bangalore not only by being lighter in weight and more translucent but also by the chukka/yarn-resist in the body check, and by the warp tie-dye of the borders. The weaving takes place in Molakalmuru Taluk in Chitradurga District about 250 kms from the capital city Bangalore by traditional weavers of the Sokula Sali, Pattu Sali, and Padma Sali communities. Molakalmuru silks with its all over patterned body, borders and end-piece are woven with twisted silk warp with less twist in the weft and metallic yarn/zari as extra warp and weft provide the texture and drape to the wearer. Often these saris are woven with contrast border and pallu/end-piece, with the body of the sari woven with a different colored warp and weft giving the sari a two-toned effect. The weavers use 3 shuttles on either side of the sari in the Korvai technique. Traditionally the borders are designed with two stripes, while stripes and check patterns with motifs are used in the body. Maroon, red, blue, mustard, green, yellow, pink and black are the traditional color palate, with motifs of the swan, lotus, peacock, mango, Shiva seed considered auspicious. More than 3500 traditional weaves continue to weave the Molakalmuru silks.

Molakalmuru is a traditional saree from Karnataka state. The raw materials used to weave this saree are mulberry filature silk for the warp and charkha silk for the weft. The weaving is done mainly on pit looms with either the fly shuttle or throw shuttle technique. Three shuttles are used: one shuttle for body portion and two shuttles for both the borders. Molakalmuru silks are distinguished from their sister silk weaving traditions in Mysore and Bangalore not only by being lighter in weight and more translucent but also by the chukka/yarn-resist in the body check, and by the warp tie-dye of the borders. The weaving takes place in Molakalmuru Taluk in Chitradurga District about 250 kms from the capital city Bangalore by traditional weavers of the Sokula Sali, Pattu Sali, and Padma Sali communities. Molakalmuru silks with its all over patterned body, borders and end-piece are woven with twisted silk warp with less twist in the weft and metallic yarn/zari as extra warp and weft provide the texture and drape to the wearer. Often these saris are woven with contrast border and pallu/end-piece, with the body of the sari woven with a different colored warp and weft giving the sari a two-toned effect. The weavers use 3 shuttles on either side of the sari in the Korvai technique. Traditionally the borders are designed with two stripes, while stripes and check patterns with motifs are used in the body. Maroon, red, blue, mustard, green, yellow, pink and black are the traditional color palate, with motifs of the swan, lotus, peacock, mango, Shiva seed considered auspicious. More than 3500 traditional weaves continue to weave the Molakalmuru silks.

Moonj/Sarkanda Grass Furniture of Haryana,

Munj Grass craft of Haryana is more popularly known as sarkanda craft. The Culm of this Asiatic grass is used to create ropes and baskets. The main stalk of sarkanda grass dries up during winter and the grass is harvested. The thick part of the grass is used in making stools and the outer skin makes for thatch. The leaf of the grass is called munj. The munj is twisted tightly to create ropes. These ropes are then used to create web like structure on charpoi and muda. The muda can vary in size by height. Now a day's many contemporary functional products are made. For instance big sized chairs, light weight sofa sets for the living rooms. The other products include Chairs, Changeri, Boiya (bread basket), Sindhora (pear shaped basket), Kharola (fodder basket) chatai, chik etc. The Asiatic Sarkanda grass is used for a variety of purposes. The main stalk of sarkanda grass dries up during winter and the grass is harvested. The thick part of the grass is used in making furniture items; its outer skin makes for thatch. The leaf of the grass is called moonj. The moonjis twisted tightly to create ropes. These ropes are then used to create web like structure on charpoi / traditional wood legged rope beds and muda/stool and other pieces of furniture also called muda. Made by aligning sarkanda in a criss-cross construction with two concentric cylindrical layers of reeds, each twisted in opposite directions, to form shallow hyperbolic paraboloids that are locked together by binding ropes at many levels along the cylinder. The structure thus formed is extremely stable and strong. The open edges are cut and bound by rope and fiber trimmings that are tied along the spine its edges are secured with moonj ropes with which the seat is also woven. Now a day's many contemporary functional products are made. For instance all sizes of moodas, light weight sofa sets for the garden and living rooms. The other products include varities of baskets, floor mats/ chatai, window and door blinds/chiks, Jhadoo/broom etc. These is a wide spread craft with craftspeople spread across Gurgaon, Farukhnagar, Rewari, Mayan, Kund, Chandpur, Khori Garhi-Bolni ,Moondreya-Kheraj, Beval, Mahendragarh, Dongra Aheer, Gujjarwaas, Khatripur and Faridabad

Munj Grass craft of Haryana is more popularly known as sarkanda craft. The Culm of this Asiatic grass is used to create ropes and baskets. The main stalk of sarkanda grass dries up during winter and the grass is harvested. The thick part of the grass is used in making stools and the outer skin makes for thatch. The leaf of the grass is called munj. The munj is twisted tightly to create ropes. These ropes are then used to create web like structure on charpoi and muda. The muda can vary in size by height. Now a day's many contemporary functional products are made. For instance big sized chairs, light weight sofa sets for the living rooms. The other products include Chairs, Changeri, Boiya (bread basket), Sindhora (pear shaped basket), Kharola (fodder basket) chatai, chik etc. The Asiatic Sarkanda grass is used for a variety of purposes. The main stalk of sarkanda grass dries up during winter and the grass is harvested. The thick part of the grass is used in making furniture items; its outer skin makes for thatch. The leaf of the grass is called moonj. The moonjis twisted tightly to create ropes. These ropes are then used to create web like structure on charpoi / traditional wood legged rope beds and muda/stool and other pieces of furniture also called muda. Made by aligning sarkanda in a criss-cross construction with two concentric cylindrical layers of reeds, each twisted in opposite directions, to form shallow hyperbolic paraboloids that are locked together by binding ropes at many levels along the cylinder. The structure thus formed is extremely stable and strong. The open edges are cut and bound by rope and fiber trimmings that are tied along the spine its edges are secured with moonj ropes with which the seat is also woven. Now a day's many contemporary functional products are made. For instance all sizes of moodas, light weight sofa sets for the garden and living rooms. The other products include varities of baskets, floor mats/ chatai, window and door blinds/chiks, Jhadoo/broom etc. These is a wide spread craft with craftspeople spread across Gurgaon, Farukhnagar, Rewari, Mayan, Kund, Chandpur, Khori Garhi-Bolni ,Moondreya-Kheraj, Beval, Mahendragarh, Dongra Aheer, Gujjarwaas, Khatripur and Faridabad

Mosaic Decorative Art in Chandigarh,

Mosaic is defined as the art of creating images with an assemblage of small pieces of coloured glass, stone, or other materials. In the early 1960s, a government official from Chandigarh, Mr. Nek Chand Saini redefined the word. What started out as a hobby, gradually developed and grew over several acres and comprised of a series of interlinking courtyards dotted with hundreds of sculptures made up of mosaic art. Although an attempt to beautify his city, this was deemed as an illegal act-a development in a forbidden area which by rights should have been demolished. However the officials took an enlightened decision to commission Mr. Nek Chand to complete his work. He used urban waste materials like bottles, tin cans, broken plugs, plates, and saucers to create patterns and textures; and mute rocks to create art. These came together to form what is known today as the Rock Garden. The first phase of the Rock Garden was a small canyon. The canyon was divided into chambers, each dotted with human and animal forms in concrete and broken ceramic glass.

Mosaic is defined as the art of creating images with an assemblage of small pieces of coloured glass, stone, or other materials. In the early 1960s, a government official from Chandigarh, Mr. Nek Chand Saini redefined the word. What started out as a hobby, gradually developed and grew over several acres and comprised of a series of interlinking courtyards dotted with hundreds of sculptures made up of mosaic art. Although an attempt to beautify his city, this was deemed as an illegal act-a development in a forbidden area which by rights should have been demolished. However the officials took an enlightened decision to commission Mr. Nek Chand to complete his work. He used urban waste materials like bottles, tin cans, broken plugs, plates, and saucers to create patterns and textures; and mute rocks to create art. These came together to form what is known today as the Rock Garden. The first phase of the Rock Garden was a small canyon. The canyon was divided into chambers, each dotted with human and animal forms in concrete and broken ceramic glass.

Moti Bharat Bead Embroidery of Gujarat,

Moti Bharat Kaam is a form of bead embroidery work which is practised by women of certain pastoral tribes in Gujarat. They use glittering, colourful beads and do extremely intricate work to create patterns on the fabric. They stitch the beads displaying geometric designs, interwoven textures and are coupled with some mirror work. The colour of the beads is not very diverse and hence only primary colours along with white are used to make this kind of embroidery. [gallery ids="177997,177998,177999"]

Moti Bharat Kaam is a form of bead embroidery work which is practised by women of certain pastoral tribes in Gujarat. They use glittering, colourful beads and do extremely intricate work to create patterns on the fabric. They stitch the beads displaying geometric designs, interwoven textures and are coupled with some mirror work. The colour of the beads is not very diverse and hence only primary colours along with white are used to make this kind of embroidery. [gallery ids="177997,177998,177999"]

Mud Murals and Paintings/Abharai of Kutch, Gujarat,

Elaborate mud murals and paintings which decorate walls, furniture, and the shelves where kitchenware is stored, called Abharai murals and paintings can be seen in homes in Kutch. Designs are similar to the embroidery motifs with borders, patterns, circles, squares and other geometric shapes combined with images of animals, birds, insects, and trees. These home decorations are embellished with mica, mirrors and embossed metal.

Elaborate mud murals and paintings which decorate walls, furniture, and the shelves where kitchenware is stored, called Abharai murals and paintings can be seen in homes in Kutch. Designs are similar to the embroidery motifs with borders, patterns, circles, squares and other geometric shapes combined with images of animals, birds, insects, and trees. These home decorations are embellished with mica, mirrors and embossed metal.

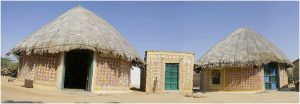

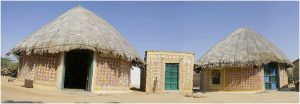

Mudwall Painting of Kutch, Gujarat,

Mud and mirror work is known as Lipan Kaam. It is a traditional mural craft of Kutch. It is also called as Chittar Kaam. The origins of Lipan Kaam are unknown. Various communities in Kutch do mud-relief work and have their own distinct style of lipan kaam. This makes it even harder to trace the roots of Lipan Kaam.

Mud and mirror work is known as Lipan Kaam. It is a traditional mural craft of Kutch. It is also called as Chittar Kaam. The origins of Lipan Kaam are unknown. Various communities in Kutch do mud-relief work and have their own distinct style of lipan kaam. This makes it even harder to trace the roots of Lipan Kaam.

Muga Silk Weaving of Assam,

Muga Silk (Antheraea assamensis) is a variety of wild silk geographically tagged to the state of Assam in India. It is not available in any other country in the world. The silk is known for its extreme durability and has a natural yellowish-golden tint with a shimmering, glossy texture. This silk can be hand-washed and its lustre increases after every wash. The fabric absorbs ultraviolet rays to such an extent that it shields the body from its effects. The fabric is woven on fly shuttle frame looms.

Muga Silk (Antheraea assamensis) is a variety of wild silk geographically tagged to the state of Assam in India. It is not available in any other country in the world. The silk is known for its extreme durability and has a natural yellowish-golden tint with a shimmering, glossy texture. This silk can be hand-washed and its lustre increases after every wash. The fabric absorbs ultraviolet rays to such an extent that it shields the body from its effects. The fabric is woven on fly shuttle frame looms.

Mukka Embroidery of Gujarat,

Mukka embroidery is done using fine metallic threads over the fabric to design beautiful patterns and motifs. It is unique to the pastoral tribe of Meghwal community who dwell in the Banni region of Kutch. The mukka signifies stellar constellations which are formed with circular patterns using the metal threads. In Banni, mukka is also used to create garments like chogas, cholas and kanjaras. [gallery ids="178002,178003,178004,178005"]

Mukka embroidery is done using fine metallic threads over the fabric to design beautiful patterns and motifs. It is unique to the pastoral tribe of Meghwal community who dwell in the Banni region of Kutch. The mukka signifies stellar constellations which are formed with circular patterns using the metal threads. In Banni, mukka is also used to create garments like chogas, cholas and kanjaras. [gallery ids="178002,178003,178004,178005"]