Khabdan- Pile Carpets of Ladakh,

The tools needed for this craft are thisha- vertical frame loom, dhunki- hammer, chamba- scissors, tee- knife used to cut knots, chakda- rod for making loops and panja- beating device. Motifs such as khorlo, medallion, snow-lion, frog-step etc are hugely popular in the adorning of the khabdans.

The tools needed for this craft are thisha- vertical frame loom, dhunki- hammer, chamba- scissors, tee- knife used to cut knots, chakda- rod for making loops and panja- beating device. Motifs such as khorlo, medallion, snow-lion, frog-step etc are hugely popular in the adorning of the khabdans.

Khadi Printing of Ahemedabad, Gujarat,

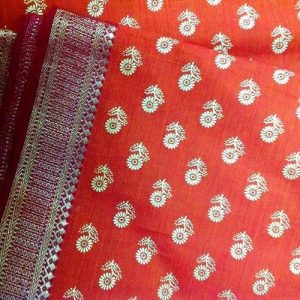

Khhadi prints are associated with ritual and ceremonial textiles. The picchwais, temple cloths, turban cloths are often seen having this print. Ahmedabad region is the centre of production for Khhadi printing in Gujarat. The process of creating this print involves stamping the khhadi paste- a mixture of zinc oxide and glue, on which gold or silver powder is sprinkled. The powder sticks itself to the rich paste almost permanently and creates an ornamental look. Owing to the appearance and the material used, khhadi prints have a unique aura which makes it a symbol of auspiciousness and divinity.

Khhadi prints are associated with ritual and ceremonial textiles. The picchwais, temple cloths, turban cloths are often seen having this print. Ahmedabad region is the centre of production for Khhadi printing in Gujarat. The process of creating this print involves stamping the khhadi paste- a mixture of zinc oxide and glue, on which gold or silver powder is sprinkled. The powder sticks itself to the rich paste almost permanently and creates an ornamental look. Owing to the appearance and the material used, khhadi prints have a unique aura which makes it a symbol of auspiciousness and divinity.

Khadi Weaving of Ahmedabad, Gujarat,

Khadi has been a symbol of independence and great jubilation for Indians. The cotton is spun into yarn on the charkha and then woven on a loom. It's story is inticately connected with the story of India's colonial past and the subsequent freedom from it. The khadi weaving industry in Ahmedabad, has encouraged experimentation of the charkha. the traditional tool for spinning khadi. A wide range of khadi products and their variants are available at the Gandhi Ashram in Ahmedabad and across various khadi bhandars in the state.

Khadi has been a symbol of independence and great jubilation for Indians. The cotton is spun into yarn on the charkha and then woven on a loom. It's story is inticately connected with the story of India's colonial past and the subsequent freedom from it. The khadi weaving industry in Ahmedabad, has encouraged experimentation of the charkha. the traditional tool for spinning khadi. A wide range of khadi products and their variants are available at the Gandhi Ashram in Ahmedabad and across various khadi bhandars in the state.

Khana of Guledgudd, Karnataka,

Guledgudda Khana is a fabric woven with pure cotton threads and silk yarns by the traditional weavers from Guledgudda and its surrounding villages, who invented and preserved this craft. The unique designs produced by using dyed yarns represent the traditions followed by the people of some regions of Karnataka and Maharashtra. The motifs used for the designs in the Guledgudda cluster are inspired by nature, the ancient stone sculptures of Badami and from the Hindu mythology. These designs are well accepted by the people in this region as they have a strong belief in them. The Khana fabric has been in existence for almost 200 years and continues to be popular even today. However, except for the traditional designs, no other designs are accepted by the wearers of Khana.

Guledgudda Khana is a fabric woven with pure cotton threads and silk yarns by the traditional weavers from Guledgudda and its surrounding villages, who invented and preserved this craft. The unique designs produced by using dyed yarns represent the traditions followed by the people of some regions of Karnataka and Maharashtra. The motifs used for the designs in the Guledgudda cluster are inspired by nature, the ancient stone sculptures of Badami and from the Hindu mythology. These designs are well accepted by the people in this region as they have a strong belief in them. The Khana fabric has been in existence for almost 200 years and continues to be popular even today. However, except for the traditional designs, no other designs are accepted by the wearers of Khana.

Khand/ Khan Blouse Weaving of Maharashtra,

Khan fabric is a woven butidar textile piece, originally made in 30 inches widths. It was usually used for making cholis and blouses. It is now woven using fly shuttles in a pit-loom with a lattice dobby attachment taking 60/40 counts coloured warp and weft yarns. The finished products include saris, scarfs, and dress materials.

Khan fabric is a woven butidar textile piece, originally made in 30 inches widths. It was usually used for making cholis and blouses. It is now woven using fly shuttles in a pit-loom with a lattice dobby attachment taking 60/40 counts coloured warp and weft yarns. The finished products include saris, scarfs, and dress materials.

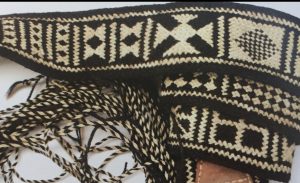

Kharel Textile of Gujarat,

Since ancient times, cattle have been used to carry load and help in transportation. The art of weaving kharel emerged with this demand and there was a need to create a sturdy transport mechanism. The kharel is a tough, sustainable textile that allows goods to be transported and by the animals with ease. These products are easy to maintain and provide strong support. [gallery ids="177988,177989,177987"]

Since ancient times, cattle have been used to carry load and help in transportation. The art of weaving kharel emerged with this demand and there was a need to create a sturdy transport mechanism. The kharel is a tough, sustainable textile that allows goods to be transported and by the animals with ease. These products are easy to maintain and provide strong support. [gallery ids="177988,177989,177987"]

Khatris of Dhamadka Block-Printed and Resist-Dyed Textiles,

Khatris, a community of fabric dyers and printers living mainly in states of Gujarat and Rajasthan are known for their age-old art of fabric printing and dyeing. They exude immense prowess in making resist-dyed fabrics using wax resist (batik) and tied resist (bandhani) fabrics. They are also responsible for making Kutch as a major center of handmade textiles. They also work in handmade block printing on cotton with handmade natural dyes. In the 17th century, the khatri community settled at the banks of the Saran river in a town called Dhamadka Dhamadka district has become known for their expertise in high-quality block printed textiles and for the use of natural dyes. [gallery ids="176356,176357,176358"] [gallery ids="176365,176364,176363,176362,176361,176360,176359"]

Khatris, a community of fabric dyers and printers living mainly in states of Gujarat and Rajasthan are known for their age-old art of fabric printing and dyeing. They exude immense prowess in making resist-dyed fabrics using wax resist (batik) and tied resist (bandhani) fabrics. They are also responsible for making Kutch as a major center of handmade textiles. They also work in handmade block printing on cotton with handmade natural dyes. In the 17th century, the khatri community settled at the banks of the Saran river in a town called Dhamadka Dhamadka district has become known for their expertise in high-quality block printed textiles and for the use of natural dyes. [gallery ids="176356,176357,176358"] [gallery ids="176365,176364,176363,176362,176361,176360,176359"]

Khatumband and Pinjrakari Woodwork of Kashmir,

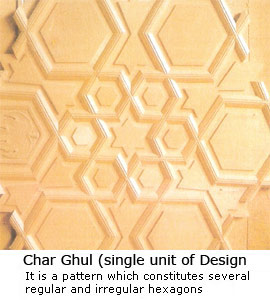

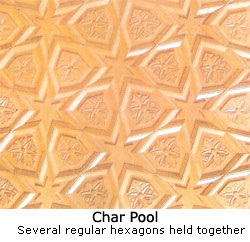

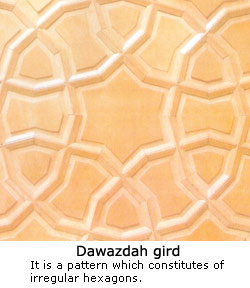

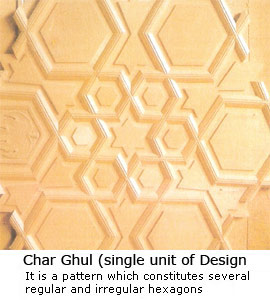

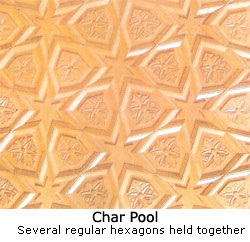

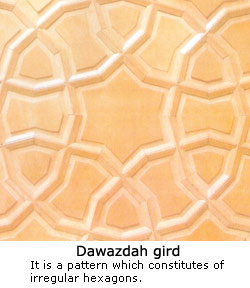

Khatumband is a craft unique to Kashmir. It uses thin geometric sheets of deodar wood which are cut and fitted into a double-grooved batten like a complicated jig saw; each piece so carved that it fits perfectly into the other. Large spaces, like walls and ceilings are clad in this technique by a repeat pattern method. The entire structure pieced together, lasting for over several hundred years without the use of a single nail. The Khatumband technique has been widely used in the contruction of Kashmir`s doongas/floating house boats and the shikaras/ the boats used in the rivers and lakes for door-to-door selling and transport. The other products made with this technique include boxes, bowls, screens, panels, bedsteads, cupboards, and cabinets. Pinjrakari, an allied technique is an intricate carving of lattice and trellis work done in light wood that is used on windows, doors, ventilators, railings and ornamental partitions and screens. With no nails used in this technique; the precise cutting, fitting and joinery holds the piece together.. The pinjra frames are pasted on with handmade paper in an effort to reduce the wind chill while allowing a filtered light through.

Khatumband is a craft unique to Kashmir. It uses thin geometric sheets of deodar wood which are cut and fitted into a double-grooved batten like a complicated jig saw; each piece so carved that it fits perfectly into the other. Large spaces, like walls and ceilings are clad in this technique by a repeat pattern method. The entire structure pieced together, lasting for over several hundred years without the use of a single nail. The Khatumband technique has been widely used in the contruction of Kashmir`s doongas/floating house boats and the shikaras/ the boats used in the rivers and lakes for door-to-door selling and transport. The other products made with this technique include boxes, bowls, screens, panels, bedsteads, cupboards, and cabinets. Pinjrakari, an allied technique is an intricate carving of lattice and trellis work done in light wood that is used on windows, doors, ventilators, railings and ornamental partitions and screens. With no nails used in this technique; the precise cutting, fitting and joinery holds the piece together.. The pinjra frames are pasted on with handmade paper in an effort to reduce the wind chill while allowing a filtered light through.

Khatwa/Applique and Patch Work Embroidery of Bihar,

The appliqué and patchwork of Bihar is locally called Khatwa and is commonly found on wall hangings, shamianas (or decorative tents and canopies that are used on festive occasions, and on religious and social ceremonies), and now even on saris, dupattas, cushion covers, table cloths, and curtains. The craft uses waste pieces of cloth as its raw material and is usually done with white cloth on bright backgrounds like red or orange. So fine was the work that, in the past, the articles produced were used by kings, emperors, and the nobility. The motifs include human figures, trees, flowers, animals, and birds. Circular cut-work is for the central motifs and quarter-circles are used for the corners. Kanats or walls of tents have tree forms with animal figures. Usually, men cut the patterns and the women do the stitching. Appliqué work is also done by women on their personal garments; the colors ranging from scarlet, orange, and yellow, to pale green, mauve, and white. In garments like caps and blouses, embroidery is combined with appliqué.

The appliqué and patchwork of Bihar is locally called Khatwa and is commonly found on wall hangings, shamianas (or decorative tents and canopies that are used on festive occasions, and on religious and social ceremonies), and now even on saris, dupattas, cushion covers, table cloths, and curtains. The craft uses waste pieces of cloth as its raw material and is usually done with white cloth on bright backgrounds like red or orange. So fine was the work that, in the past, the articles produced were used by kings, emperors, and the nobility. The motifs include human figures, trees, flowers, animals, and birds. Circular cut-work is for the central motifs and quarter-circles are used for the corners. Kanats or walls of tents have tree forms with animal figures. Usually, men cut the patterns and the women do the stitching. Appliqué work is also done by women on their personal garments; the colors ranging from scarlet, orange, and yellow, to pale green, mauve, and white. In garments like caps and blouses, embroidery is combined with appliqué.

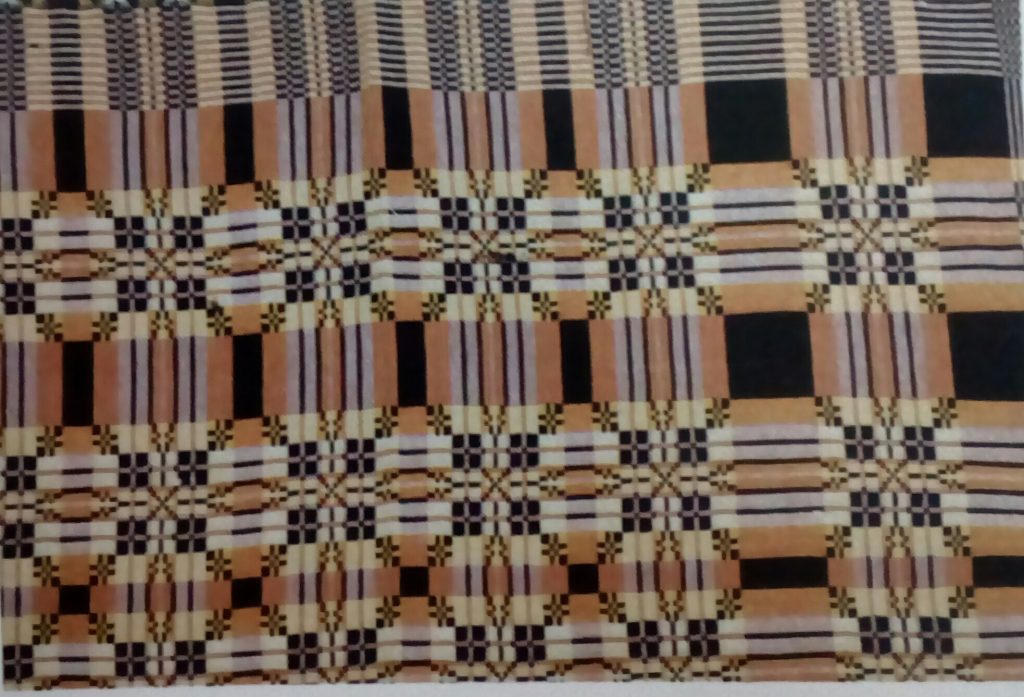

Khes of Panipat, Haryana,

The need for covering the floors of the houses with cotton rather than woollen spreads popular in Persia, brought in the durree and the khes. The hangings in the colourful tents led to the invention of the floral designs on rough cloth. The textiles for use in ceremonials became even more variegated under the Mughals; the animated bright colours of Haryana fabrics are likely to spread more and more to the entire world, as the drabness of the 'technology-run-mad' syndrome demands richness for the eyes. Panipat, a historical town of India, presently known as a city of Handloom was once famous for its khes weaving. These were woven in a double-cloth weave with cotton yarn, making it thick enough to be used as a shawl or a wrap. It was more popularly used as a bedding material. With the advent of the power-loom, the handloom sector of Panipat suffered a setback. However, while the carpet and durree weaving industries survived, khes weaving died out owing to its time consuming complex weaving.

The need for covering the floors of the houses with cotton rather than woollen spreads popular in Persia, brought in the durree and the khes. The hangings in the colourful tents led to the invention of the floral designs on rough cloth. The textiles for use in ceremonials became even more variegated under the Mughals; the animated bright colours of Haryana fabrics are likely to spread more and more to the entire world, as the drabness of the 'technology-run-mad' syndrome demands richness for the eyes. Panipat, a historical town of India, presently known as a city of Handloom was once famous for its khes weaving. These were woven in a double-cloth weave with cotton yarn, making it thick enough to be used as a shawl or a wrap. It was more popularly used as a bedding material. With the advent of the power-loom, the handloom sector of Panipat suffered a setback. However, while the carpet and durree weaving industries survived, khes weaving died out owing to its time consuming complex weaving.

Khes weaving in Punjab,

A popular thick cotton wraparound for men, the khes is used as a means of protection against harsh winds. It is made of coarse yarn. Often half the yarn is dyed black and chequered designs are woven in black and white. The need for covering the floors of the houses with cotton rather than woollen spreads popular in Persia, brought in the durree and the khes. The hangings in the colourful tents led to the invention of the floral designs on rough cloth, The textiles for use in ceremonials became even more variegated under the Mughals; the animated bright colours of Haryana fabrics are likely to spread more and more to the entire world, as the drabness of the 'technology-run-mad' syndrome demands richness for the eyes.

A popular thick cotton wraparound for men, the khes is used as a means of protection against harsh winds. It is made of coarse yarn. Often half the yarn is dyed black and chequered designs are woven in black and white. The need for covering the floors of the houses with cotton rather than woollen spreads popular in Persia, brought in the durree and the khes. The hangings in the colourful tents led to the invention of the floral designs on rough cloth, The textiles for use in ceremonials became even more variegated under the Mughals; the animated bright colours of Haryana fabrics are likely to spread more and more to the entire world, as the drabness of the 'technology-run-mad' syndrome demands richness for the eyes.

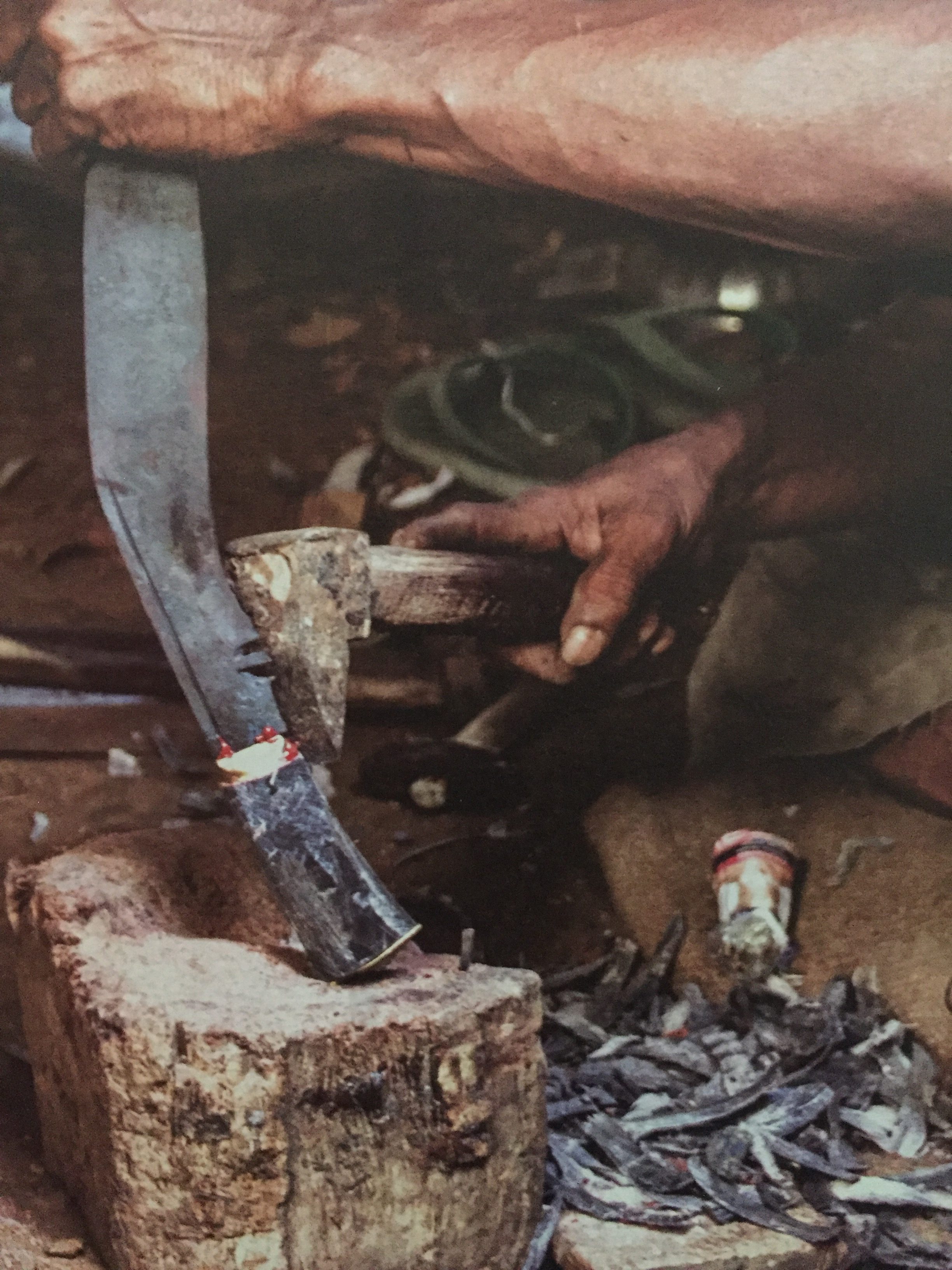

Khukri/Gurkha Knife of Uttarakhand,

The khukri is a Gurkha knife celebrated for its blade. The boomerang-shaped blade gas different curvatures at the spine and the at the edge where it is supported by a handle made from wood. The design makes it wide and thick at the center and tapering at the ends. the unusual curve at the center of mass gives it momentum to inflict deep cuts and slashes without much effort. The narrower the blade at the base also works as a cutting edge. the handle is curved and is flared butt and prominently ribbed center give the handle a marvelous grip. It is made from the hard wearing woods a bull horn. the tang of the blade extends all the way through the handle, and the end is hammered flat yo secure the entire knife. a traditional khukri is accompanied by two finer sized knives fitted into its scabbard- a blunt chakmak for sharpening the khukri blade and a sharp-edged karda for skinning.

The khukri is a Gurkha knife celebrated for its blade. The boomerang-shaped blade gas different curvatures at the spine and the at the edge where it is supported by a handle made from wood. The design makes it wide and thick at the center and tapering at the ends. the unusual curve at the center of mass gives it momentum to inflict deep cuts and slashes without much effort. The narrower the blade at the base also works as a cutting edge. the handle is curved and is flared butt and prominently ribbed center give the handle a marvelous grip. It is made from the hard wearing woods a bull horn. the tang of the blade extends all the way through the handle, and the end is hammered flat yo secure the entire knife. a traditional khukri is accompanied by two finer sized knives fitted into its scabbard- a blunt chakmak for sharpening the khukri blade and a sharp-edged karda for skinning.

Khunda/Bamboo Staves of Punjab,

In Batala town the Khunda/ Bamboo staves are crafted for use by the local Punjabi farming community, the nomadic cattle herding Gujjars, and the Nihang warriors, also used as an essential part of the Bhangra dance these iron tipped staves serve the purpose of a walking aid and weapon.

The Staves made from whole bamboo poles are cut to size so that the natural form of the bamboo is maintained. The end of the stave is sharply pointed and shaped to be fitted and clad with an iron sheet that makes it an effective weapon. The pole is tinted a reddish brown color and ornamented with poker work, brass strips and brass nails, kokas.

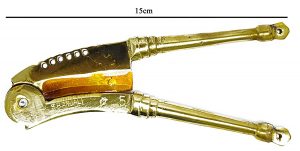

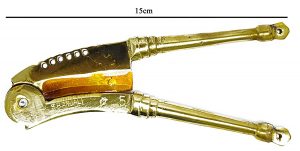

Knives and Betel Nut Crackers of Gujarat,

Areca/ betel nut accessories like nut-crackers and knives are some of the accessories and functional items which grew around the paan-supari culture in India. This tradition, going back at least 2,000 recorded years, continues till today. The betel nut is ingested for a variety of reasons: it is a digestive, it has medicinal properties, and it is also chewed for pleasure. Betel-nut accessories include metallic spittoons, trays, nut-crackers, and lime boxes. The paandan or paandani, a box to store betel leaf, which is served after a meal also has compartments to store the additives like areca nut, tobacco, mukhvaas, mouth refreshments. Perforated lids on each compartments ensure that there is air circulating within the box. The most ornamented of all metal products, the sudi, the nutcracker was once found in traditional households. These were fashioned to different forms, ranging from human figures to animals, birds and floral shapes. Cast in two parts, the sudi is joined at one end with a rivet. [gallery ids="176350,176349,176348"]

Areca/ betel nut accessories like nut-crackers and knives are some of the accessories and functional items which grew around the paan-supari culture in India. This tradition, going back at least 2,000 recorded years, continues till today. The betel nut is ingested for a variety of reasons: it is a digestive, it has medicinal properties, and it is also chewed for pleasure. Betel-nut accessories include metallic spittoons, trays, nut-crackers, and lime boxes. The paandan or paandani, a box to store betel leaf, which is served after a meal also has compartments to store the additives like areca nut, tobacco, mukhvaas, mouth refreshments. Perforated lids on each compartments ensure that there is air circulating within the box. The most ornamented of all metal products, the sudi, the nutcracker was once found in traditional households. These were fashioned to different forms, ranging from human figures to animals, birds and floral shapes. Cast in two parts, the sudi is joined at one end with a rivet. [gallery ids="176350,176349,176348"]

Kodali Karuppur Sari Weaving of Tamil Nadu,

The kodali karrupur sari derives its name from the village of Kodali Karrupur, on the northern bank of the Kollidam river, in Tiruchy district of Tamil Nadu. Till the beginning of the twentieth century, Kodali Karrupur was famous for its karpur saris (as well as dhotis and furnishings); however, by the early years of the twentieth century, lack of patronage and competition with less expensive mill-made saris reduced the craft to virtual extinction.

The kodali karrupur sari derives its name from the village of Kodali Karrupur, on the northern bank of the Kollidam river, in Tiruchy district of Tamil Nadu. Till the beginning of the twentieth century, Kodali Karrupur was famous for its karpur saris (as well as dhotis and furnishings); however, by the early years of the twentieth century, lack of patronage and competition with less expensive mill-made saris reduced the craft to virtual extinction.

Maratha rulers who ruled Thanjavur after the Naikas were entranced by the kodali karrupur, and used it as a wedding sari. Under their patronage it was woven in the royal palace at Thanjavur.

The karrupur sari is a 'fine cotton muslin in which discontinuous supplementary zari patterns were woven in the jamdani technique. The muslin was were then resist painted by hand and dyed in various natural colours, giving a variety of rich but sombre red tones to the fabric'.

The uniqueness of the karrupur sari lies in its combination of hand-painting (using vegetable colours), block-printing (using vegetable colours), and brocade weaving, three distinct and different techniques. The motif has an uncoloured outline, which reflects the base fabric colour. In contrast, the remaining area is filled in with two or three colours like red, black, yellow, or blue. The uncoloured motif outline is obtained by resisting with a wax line (traditionally, using a wax batik pen). The painting/printing is done is a style distinct from the one common today. 'In present-day painting, the form of the design is shown in a dark line and the areas are filled with colour'; 'in the karrupur sari, the form of the design line is left with the white background of the fabric and the areas are filled [in] with colour'. The coloured areas are created by painting or printing with blocks - the cloth is not dyed.

The weaving of the fabric is combined with zari in the jamdani technique - motifs like the star in the border and tilakam in the body of the sari are woven with the zari weft. In the pallu, those areas that are to be painted/printed have a cotton weft; the rest of the ground is woven with the zari weft. The zari shines through the colours that are painted or block-printed, creating an effect that is particular to the kodali karrupur sari.

Perhaps the first effort to revive the karpur sari was made in 1981 by the Weavers' Service Centre in Madras. (A karpur sari was exhibited in the Vishwakarma Exhibition in London; a specimen of the sari is available in the Museum of the Government College of Arts & Crafts, Chennai).

Kolam Painting of Andhra Pradesh,

The art of floor painting in Andhra Pradesh is known as Muggulu. Each day of the week has a selected design or symbol associated with it: shivpith for Monday, kalipith for Tuesday, swastika for Wednesday, lakshmi for Friday, and so on. The basic motifs include the lotus, the swastika, and conch shells and discs. The Shri figures are very prominent here; Shri is another name for Lakshmi, the Goddess of fortune, who is also the goddess of fertility. Shri also represents the centre of a mystic grill of geometric patterns. A simple one has two conch shells with vertical lines on either side. The lotus appears often, and is depicted differently each time. It appears as a triangular grille formation, as a magnificent figure in eight petals (ashtadal kamal), and as an elaboration of a conventional motif like the swastika. In all the designs, the moving lines make circuitous movements and finally return to the base.

The art of floor painting in Andhra Pradesh is known as Muggulu. Each day of the week has a selected design or symbol associated with it: shivpith for Monday, kalipith for Tuesday, swastika for Wednesday, lakshmi for Friday, and so on. The basic motifs include the lotus, the swastika, and conch shells and discs. The Shri figures are very prominent here; Shri is another name for Lakshmi, the Goddess of fortune, who is also the goddess of fertility. Shri also represents the centre of a mystic grill of geometric patterns. A simple one has two conch shells with vertical lines on either side. The lotus appears often, and is depicted differently each time. It appears as a triangular grille formation, as a magnificent figure in eight petals (ashtadal kamal), and as an elaboration of a conventional motif like the swastika. In all the designs, the moving lines make circuitous movements and finally return to the base.