Embroidery of Karnataka,

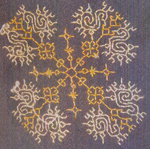

The word Kasuti is believed to be derived from word kashidakari that means embroidery by hand. Few scholars also say that the name Kasuti is derived from the words Kai (meaning hand) and Suti (meaning cotton), indicating an activity that is done using cotton and hands. This living tradition is done on Ilkal saris worn by Brides of Karnataka. GEOGRAPHY: In Uttar Kannada region of Karnataka, bordering Maharashtra there is a meta-cluster called Belgaum that includes district of Dharwad. The district of Dharwad has many production clusters; Dharwad, Hubli, Narendra Village, Kalghatgi taluka which are involved in a special embroidery craft on saris and blouses. The embroidery technique is named as Kasuti. HISTORY: It is believed that the embroidery was developed mostly in the Lingayat community and later spread to entire Karnataka region. There are literary references dating back to 15th century. It is one of the 64 arts in the Mysore kingdom. Kasuti is not merely an embellishment but an important part of the sari. The motifs are derived from the Shaivite philosophy. SIGNIFICANCE: Like other embroidery crafts of India, Kasuti is also long cherished women dominated industry. The skill requires prolonged skill and vigorous training. Every woman is expected to adorn their blouse and sari with kasuti embroidery. Woman in every household is adept in the craft. The embroidery is done for a reason and not mere adornment of fabric. Chandrakali sari is a bridal wear adorned with kasuti embroidery, which is woven in typical borders. This is the only bridal wear in India with black or blue black colour which is considered very auspicious. The blouses of the sari are hand woven and embellished with embroidery. Such blouses were considered the most appropriate blouses for expectant mother. Traditionally the embroidery was used on fabrics related to rituals of marriage, childbirth and festivities as well as daily wear for women and children, and on household accessories. TYPES OF STITCHES: Kasuti embroidery consists of four prominent stitches; gavanti is a double running stitch, murgai is a zig-zag running stitch, neygi; darning stitch and menthe (name derived from vernacular name for the fenugreek seed) is a cross stitch which is used mostly in filling the background areas. MOTIFS: As the Lingayats are deep routed in Shaivite religion, the motifs are also derived from religious philosophy. The motifs most commonly used in the embroidery are mainly gopuram (temple tower), ratha (chariot), conch shell, linga, lotus and animals. Sometimes border motifs representing a field of crop ready for harvest are also depicted.

The word Kasuti is believed to be derived from word kashidakari that means embroidery by hand. Few scholars also say that the name Kasuti is derived from the words Kai (meaning hand) and Suti (meaning cotton), indicating an activity that is done using cotton and hands. This living tradition is done on Ilkal saris worn by Brides of Karnataka. GEOGRAPHY: In Uttar Kannada region of Karnataka, bordering Maharashtra there is a meta-cluster called Belgaum that includes district of Dharwad. The district of Dharwad has many production clusters; Dharwad, Hubli, Narendra Village, Kalghatgi taluka which are involved in a special embroidery craft on saris and blouses. The embroidery technique is named as Kasuti. HISTORY: It is believed that the embroidery was developed mostly in the Lingayat community and later spread to entire Karnataka region. There are literary references dating back to 15th century. It is one of the 64 arts in the Mysore kingdom. Kasuti is not merely an embellishment but an important part of the sari. The motifs are derived from the Shaivite philosophy. SIGNIFICANCE: Like other embroidery crafts of India, Kasuti is also long cherished women dominated industry. The skill requires prolonged skill and vigorous training. Every woman is expected to adorn their blouse and sari with kasuti embroidery. Woman in every household is adept in the craft. The embroidery is done for a reason and not mere adornment of fabric. Chandrakali sari is a bridal wear adorned with kasuti embroidery, which is woven in typical borders. This is the only bridal wear in India with black or blue black colour which is considered very auspicious. The blouses of the sari are hand woven and embellished with embroidery. Such blouses were considered the most appropriate blouses for expectant mother. Traditionally the embroidery was used on fabrics related to rituals of marriage, childbirth and festivities as well as daily wear for women and children, and on household accessories. TYPES OF STITCHES: Kasuti embroidery consists of four prominent stitches; gavanti is a double running stitch, murgai is a zig-zag running stitch, neygi; darning stitch and menthe (name derived from vernacular name for the fenugreek seed) is a cross stitch which is used mostly in filling the background areas. MOTIFS: As the Lingayats are deep routed in Shaivite religion, the motifs are also derived from religious philosophy. The motifs most commonly used in the embroidery are mainly gopuram (temple tower), ratha (chariot), conch shell, linga, lotus and animals. Sometimes border motifs representing a field of crop ready for harvest are also depicted.

Embroidery of Kerala,

Syrian embroidery was the first to find its way into Kerala; however, it is no longer practised here. The embroidery actually practised now is of more recent origin, having been introduced by the London Mission Society in the first quarter of the 19th century.

Syrian embroidery was the first to find its way into Kerala; however, it is no longer practised here. The embroidery actually practised now is of more recent origin, having been introduced by the London Mission Society in the first quarter of the 19th century.

Embroidery of Kutch, Gujarat,

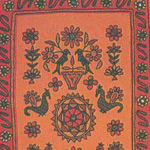

Gujarat is known for its embroidery in a variety of style and technique which is unique and diverse to other states. A woman based craft embroidery is done on 'cholis' and 'ghagras' but also on items decorating their houses, such as chaklas, wall hangings, pillow covers, quilts etc. There is perfect harmony and distribution of the colours. Applique of 'katab' is another form of decorative needlework which women prepare for special uses. The rich embroidery work of Bhuj, Rajkot, Bhavnagar, Jamnagar and Ahmadabad districts is famous in Gujarat. Different styles of embroidery developed as pastoral communities migrated to various parts of Gujarat. From Patan's Ari stitch and Saurashtra's Sadhu embroidery to the exquisite Suf, Meghwal, Rabari and Jat needlework of Kachchh, each community is identified by its own distinct style of embroidery. A tradition passed on from mother to daughter during leisure hours, embroidery brings vitality to an otherwise monotonous backdrop in the semi desert regions of Gujarat.

Gujarat is known for its embroidery in a variety of style and technique which is unique and diverse to other states. A woman based craft embroidery is done on 'cholis' and 'ghagras' but also on items decorating their houses, such as chaklas, wall hangings, pillow covers, quilts etc. There is perfect harmony and distribution of the colours. Applique of 'katab' is another form of decorative needlework which women prepare for special uses. The rich embroidery work of Bhuj, Rajkot, Bhavnagar, Jamnagar and Ahmadabad districts is famous in Gujarat. Different styles of embroidery developed as pastoral communities migrated to various parts of Gujarat. From Patan's Ari stitch and Saurashtra's Sadhu embroidery to the exquisite Suf, Meghwal, Rabari and Jat needlework of Kachchh, each community is identified by its own distinct style of embroidery. A tradition passed on from mother to daughter during leisure hours, embroidery brings vitality to an otherwise monotonous backdrop in the semi desert regions of Gujarat.

Embroidery of Madhya Pradesh,

The Banjaras of Madhya Pradesh --- found in the districts of Malwa and Nimar --- have their own distinct style of embroidery. They embroider the surface of the material, creating designs according to the weave of the cloth. The items embroidered are rumals (kerchiefs), batuas (money bags), borders for cholis (blouses), ghagras (skirts) and odhnis . The inside square of the rumal is entirely covered with embroidery. A stem stitch, done horizontally instead of vertically, is used. The needle pierces a particular area between the warp and the weft threads from below, and the thread after crossing two warp threads and weft threads is again inserted into the material; this time it comes out on the right side in line with the first stitch directly below where it ended. The patterns are geometrical and designs are created by varying colours and stitches, to give textured effects. Some motifs are emphasised by the cross-stitch and closely done herring-bone stitches divide the design into squares. The border of the rumal does not have an overall pattern but instead a running design done by counting the threads. The angular designs are achieved by vertical stitches. The inner embroidery of the rumal is similar to the embroidery done by the Mathurai tribe of Andhra Pradesh, and the embroidery at the border is similar to that found in north Bihar. Like the Mathudias of Andhra Pradesh, tassels of different shapes and forms are used. This craft is also practised by the Gondolia tribes of Malwa region, who originate from Rajasthan.

The Banjaras of Madhya Pradesh --- found in the districts of Malwa and Nimar --- have their own distinct style of embroidery. They embroider the surface of the material, creating designs according to the weave of the cloth. The items embroidered are rumals (kerchiefs), batuas (money bags), borders for cholis (blouses), ghagras (skirts) and odhnis . The inside square of the rumal is entirely covered with embroidery. A stem stitch, done horizontally instead of vertically, is used. The needle pierces a particular area between the warp and the weft threads from below, and the thread after crossing two warp threads and weft threads is again inserted into the material; this time it comes out on the right side in line with the first stitch directly below where it ended. The patterns are geometrical and designs are created by varying colours and stitches, to give textured effects. Some motifs are emphasised by the cross-stitch and closely done herring-bone stitches divide the design into squares. The border of the rumal does not have an overall pattern but instead a running design done by counting the threads. The angular designs are achieved by vertical stitches. The inner embroidery of the rumal is similar to the embroidery done by the Mathurai tribe of Andhra Pradesh, and the embroidery at the border is similar to that found in north Bihar. Like the Mathudias of Andhra Pradesh, tassels of different shapes and forms are used. This craft is also practised by the Gondolia tribes of Malwa region, who originate from Rajasthan.

Embroidery of Manipur,

This area has one kind of embroidery, which uses one stitch, in deference to the weavers in the area. This is done on the border of the phanek, which is a lungi or lower body wrap worn by women, in a dark matching shade with untwisted silk thread. The colour is usually dark red, plum, or chocolate. The lungi has dark stripes woven on a light background. The embroidery is done so finely that it does not clash with the weave and is often mistaken for it. The phanek is sometimes a plain fabric in a dark shade or with plain stripes in three colours and the embroidery is the only adornment. The most significant design in Manipur embroidery is the akoybi and the colours used are two shades of red with a little black and a touch of white. Akoybi is an elegant snake-like pattern or design, derived from the legendary snake, pakhamba (killed by the husband of a goddess, who later tried to atone for this act by imitating the pattern). Akoybi means circular, and the pattern is one circle joining the other, each broken further with a significant motif. The colours used are two shades of red, along with black and white. Hijay is another pattern where black and white, along with shades of pink, are used in a continuous pattern. Animal motifs are found on black shawls which are called Angami Naga shawls. This was previously called sami lami phee (which means warrior cloth of wild animals) and was given to brave distinguished warriors by the royalty, in recognition of their prowess and ability. The horizontal panels are woven bands of colour and the motifs include elephants and camels. The colours are bright green, red, yellow, and white. White on white appliqué embroidery done on turbans is extremely delicate. Abhala or mirror-embroidery work is done only on ras dance costume. The indigenous inhabitants of Manipur are the meithei community. They have designs called tindogbi; the inspiration is from a silk caterpillar sitting on a castor leaf and eating it. Shamilami, a combination of weaving and embroidery, is considered a high status symbol. Maibung is a natural design inspired from wood grains and hijamayak design is associated with death ceremonies.

This area has one kind of embroidery, which uses one stitch, in deference to the weavers in the area. This is done on the border of the phanek, which is a lungi or lower body wrap worn by women, in a dark matching shade with untwisted silk thread. The colour is usually dark red, plum, or chocolate. The lungi has dark stripes woven on a light background. The embroidery is done so finely that it does not clash with the weave and is often mistaken for it. The phanek is sometimes a plain fabric in a dark shade or with plain stripes in three colours and the embroidery is the only adornment. The most significant design in Manipur embroidery is the akoybi and the colours used are two shades of red with a little black and a touch of white. Akoybi is an elegant snake-like pattern or design, derived from the legendary snake, pakhamba (killed by the husband of a goddess, who later tried to atone for this act by imitating the pattern). Akoybi means circular, and the pattern is one circle joining the other, each broken further with a significant motif. The colours used are two shades of red, along with black and white. Hijay is another pattern where black and white, along with shades of pink, are used in a continuous pattern. Animal motifs are found on black shawls which are called Angami Naga shawls. This was previously called sami lami phee (which means warrior cloth of wild animals) and was given to brave distinguished warriors by the royalty, in recognition of their prowess and ability. The horizontal panels are woven bands of colour and the motifs include elephants and camels. The colours are bright green, red, yellow, and white. White on white appliqué embroidery done on turbans is extremely delicate. Abhala or mirror-embroidery work is done only on ras dance costume. The indigenous inhabitants of Manipur are the meithei community. They have designs called tindogbi; the inspiration is from a silk caterpillar sitting on a castor leaf and eating it. Shamilami, a combination of weaving and embroidery, is considered a high status symbol. Maibung is a natural design inspired from wood grains and hijamayak design is associated with death ceremonies.

Embroidery of Pakistan,

The embroideries of Pakistan are among the richest in South Asia. Traditional costumes, accessories and animal adornments embroidered by women for their families are still in use. Although the techniques, design elements and uses may be in common, many are peculiar to individual communities and distinguishable by their style, motifs and colour. Embroidery, like clothing, functions as a non-verbal form of communication and motifs, colour and composition signify an individual's group identity and occupation and, very often, social status.

The embroideries of Pakistan are among the richest in South Asia. Traditional costumes, accessories and animal adornments embroidered by women for their families are still in use. Although the techniques, design elements and uses may be in common, many are peculiar to individual communities and distinguishable by their style, motifs and colour. Embroidery, like clothing, functions as a non-verbal form of communication and motifs, colour and composition signify an individual's group identity and occupation and, very often, social status.

The embroideries of Pakistan encompass many traditions and some information is detailed below.

BALUCHI EMBROIDERY/DOCH

Baluchi embroidery (doch) is outstanding in it intricate repeating geometric patterns and colors. The Baluchi women's pashk invariably carries four panels of embroidery: a large yoke covering the chest, the sleeve cuffs and a long, narrow, rectangular pocket (pado or pandohi) that runs from the yoke to just above the hem. The embroidery is often referred to as pakka (firm or solid) as the ground fabric is completely covered in a repertoire of the fine satin (mosum), interlacing (chinnukal) herringbone (mai pusht), chain (kash), blanket square-chain, cross and couched stitches. While the distri-button of embroidery on the pushk remains more or less constant throughout Baluchistan, there are minor regional variations in the fabric of the pashk, or on pieces of coarse cotton cloth called alwan, which are then stitched on to the pashk

The edges of the sleeves and the neck opening are usually strengthened with a braid of silk and gold thread or tightly packed blanket stitches (toi) followed by a series of finely worked narrow and wide borders in a precisely defined sequence. The narrow borders are generally worked using black and white threads in a couched stitch (chamusurma), followed by chain (kash) and satin stitches (mosum), and this sequence is repeated symmetrically in all the narrow borders as they alternate with the wide borders.

BALUCHI LEATHER EMBROIDERY

Chain stitch is commonly used in Baluchi leather embroidery is also used for pashks in the areas around Nasirabad and Khanpur. These are often embroidered in Jacobabad, Sibi or its environs. Jacobabad has evolved into a major centre of Baluchi embroidery workshops, producing ornamental panels, wallets belts, traditional purses, spreads and caps, both for local demand and for export. The traditional Baluch cap or topi, over which the turban is tightly rolled and wrapped, is a deeper and more intricately embroidered version of the Sindhi topi. It is usually made of cotton with fine silk or cotton embroidery in floral or geometric patterns, incorporating minute mirrors and the occasional use of silver and gold-wrapped thread for more ceremonial wear.

CROCHET EMBROIDERY

Middle aged and older women crochet when not working in the field or home. Presently acrylic or wool is the popular base used to create lacy designs. Traditionally cotton thread was used for intricately designed bedcovers, table cloth, edging for duppattas. The craftswomen have been motivated to us 100% cotton thread for the products to be marketed by SUNGI craft shop.

EMBROIDERY FROM NWFP

The more isolated areas have retained their traditional embroidery styles, and the Kohistan region, stretching across the upper Swat and Indus Valleys, is a case in point. The people of this remote of this remote territory belong to a relatively small group of what are sometimes called Dardic people (although this is a name given them by European ethnographers and not used locally) and which also includes the inhabitants of the territory stretching from Chitral across to Gilgit, Hunza and Baltistan.

Closer to the Kohistan style of geometric cross-stitch embroidery is a type of small-scale work common to both Hunza and Chitral. Mostly confined to women's circular caps and other small items such as purses and belts, the embroidery of Hunza in particular can be extremely fine. Patterns are usually geometric and are worked in tiny cross stitch, or today only half-cross stitch. The same type of embroidery is found in Chitral, perhaps having been introduced from Hunza, and is used for similar objects: caps (very similar to the Hunza style, but usually with less deep brims), detachable cuffs and collars, and small bags. These small embroidered objects are called suru and are often found as dowry items. While they share similar geometric patterns with the Hunza embroideries, the Chitrali embroideries seem to favor colors like purple and bright green.

Embroidery is also a feature of the Kalash women's costume, in which the voluminous black robes are embroidered with orange and yellow braids around the neck and cuffs. The elaborate Kalash ceremonial headdress, the kupas, which is strikingly similar in form and decoration to the turquoise-covered headdress of Ladakhi women, is made of wool lavishly embroidered with rows of cowrie shells and with medallions of brass, shells, buttons, and metal grelots at the lower end.

FOLK EMBROIDERIES

The folk embroideries of Sindh are used as part of the traditional costumes, accessories and animal adornments are some of the more spectacular embroideries of this region. Embroidered by women for their families they are still prevalent among a number of groups scattered throughout the province. Although the techniques, design elements and uses may have commonalities, many are peculiar to individual communities and distinguishable by their style, motifs and color.

Tharparkar is part of a rambling desert that is one of the most inhospitable areas of Pakistan continues to produce some of its most special folk embroideries. The majority of its inhabitants are tightly knit groups of nomadic pastoralists, artisans and farmers, predominantly Muslim and Hindu. Muslim groups include the Soomrahs, Sammats, Sammahs, Jats, Langhas, Odhejas, Halepotas, Noorhias, Khojas, Khaskelis, Junejos, Memons, and the Baloch (made up of a number of subgroups). This non-verbal form of communication also carries symbols that represent protective talismans. Motifs, color and composition signify an individual's group identity, occupation and, social status. This is particularly the case for women, as in many parts of Tharparkar a woman who is unmarried, has children or who is widowed is immediately distinguishable by the ornaments she wears and by the shawl covering her head and shoulders.

The bhart or embroideries of Tharparkar are found in two basic styles, the pakkoh and the kacho or soof. Pakkoh is a style of dense, heavily worked embroidery that has historically been linked to the areas surrounding Diplo and Mithi in Central Tharparkar. The patterns are usually stamped on to cloth using carved wooden blocks (por) dipped in a paste made from soot, mud or powdered resin dissolved in water. Pakkoh embroidery consists of combinations of closely packed double-buttonhole, square-chain, interlaced square-chain, couched, satin, and stem stitches. Small mirrors are usually attached in a tight double-buttonhole stitch and provide focal pints in the overall pattern. Originally, pieces of naturally occurring mica were used but now mirrored glass is specially manufactured. The ground cotton or silk is usually lined and almost entirely covered with embroidery. Very often, when the silk has worn away the stitches remain intact, hence the name pakkoh, literally 'solid' or 'permanent'.

The kacho or soof style, which originated with the Sodha Rajputs in the thirteenth century, relies on the counting of threads in the ground fabric. Satin stitches, usually put in from the reverse side, lie flat on the surface, and the forms produced bear a spatial relationship to one another. The motifs are not generally marked out on the fabric; although threads are occasionally drawn out to delineate areas to be filled in. patterns worked in the soof style usually have the ground fabric visible between motifs that are immaculately constructed from fine geometric shapes. Soof embroidery is also seen in conjunction with a stem or honeycomb filling, interlacing and buttonhole stitches and mirrors. The Suthars, a group of artisans traditionally associated with wood crafts in Tharparkar, are especially renowned for the whimsical soof patterns which they carry over on to carved utilitarian wooden objects such as saddles, tools, farming implements, mortars and bowls. The Suthar Women's ingenuity in embroidering and combining simple shapes to depict natural forms finds ultimate expression in the garments they prepare as dowry gifts for their daughters and sons-in-law. Mirrors, cotton thread and floss silk are commonly used; where satin stitches are laid out on the surface on the cloth and not visible on the reverse (as in a false-satin or surface darning stitch), the embroidery is referred to as kachi tand soof (one-sided) whereas stitches visible on both sides are referred to as hakim or paki tand soof (two-sided).

The peacock found all over Tharparkar is the leitmotif of its embroidered textiles. Among the Hindu Meghwar groups who are professional embroiderers, leather workers, tanners, builders and farmers, the peacock is a metaphor for a bridegroom who comes to claim his bride from her parents. The long narrow scarf, bakano, that he is given by his future mother-in-law for his wedding day has a fanciful design of peacocks among flowers and on top of hills or dunes. The peacock is revered as a noble bird; it is the embodiment of good and is often represented as a vehicle for Saraswati, goddess of wisdom, poetry and the arts. Peacocks, as Tharri folk legends relate, are thought not to mate physically but through the medium of dance. The highly stylized pairs of birds depicted along the length of the groom's bokano symbolize the coming together of the newlyweds and the sanctity of their union. They are embroidered in a row of symmetrical rectangles alternating with columns of flower and mirrors that run along the entire length of the scarf. A longer and broader version of the bokano, the karhbandhro, is used by Rajput, Thakur and Mehgwar bridegrooms as a cummerbund for their loincloths (threto). It may be wound tightly around the waist several times, and knotted with the embroidered ends left hanging down.

Flowers symbolizing fertility and prosperity for the bridal couple are found in practically all Tharparkar wedding garments. The largest and most outstanding of these is the Meghwar man's wedding shawl or doshalo, a large mordant-dyed and resist-printed cotton shawl or maleer embroidered in the pakkoh style by the bride and her family for her wedding day. The doshalo and bokano often share a decorative theme of peacocks, and are made up of two symmetrical halves of cloth joined by a web of fine interlacing stitches called a kheelo. The doshalo is usually elaborately embroidered at its ends and has densely embroidered squares resembling flowerbeds at the four corners. It is thrown around a bride-groom's shoulders by his female relatives as he leaves to collect his bride on their wedding day, and he continues to wear it with the ends thrown forward over his shoulders for the journey and rituals that will follow at the bride's house. Occasionally it may be wound flamboyantly around his head in the form of a turban with the ends hanging down over his shoulders. When he is finally allowed to leave with his bride, the doshalo is symbolically draped around them both, each holding one end. Among some Meghwar families the doshalo is hoisted like a canopy over the newlyweds, its corners usually held by close male relatives of the bride as she takes leave of her parents. It is a treasured dowry gift and continues to be used as a shawl or spread on auspicious occasions throughout the couple's life.

The flowers represented on the Meghwar doshalo and bokano are usually renditions of desert flowers, most commonly the golharho (Coccinia cordifolia) and rohirho (Techoma undulaca), embroidered in the pakkoh style using combinations of elongated square-chain, interlaced square-chain, double-buttonhole and satin stitches. Accents may be added in satin, pattern-running or fly stitches (chanwar kani). The flowers are predominantly red, orange and white floss (untwisted) silk or cotton thread with centrally placed mirrors. Accompanying green, purple and yellow leaves are very often outlined in black stem and white back or couched stitches. As a particular printed and embroidered textile is part of the groom's wedding accessories, the bride's abochhini or shawl is also embroidered in a characteristic style and distribution of motifs (buti). Among the farming and semi-nomadic groups in Tharparkar and the adjoining areas of the Indus delta, the Sammat, Memon, Lohana, Khaskeli, Baloch and Soomrah, bridal shawls usually have scattered buds or blossoms of the akk plant (Calotropia procera) embroidered inpink or red flows silk in a typical phulkari or herringbone stitch for the petals and a green floss silk in chain or square-chain stitches for the leaves. Other stylized flowering plants such as the beyri (Zizyphus jujuba), the kanwal or lotus (Sindica nymphia) and the pat kanwar (Malva parviflora) are depicted in a unique scatter pattern either as single flowers or as clusters placed in rows around an elaborate central medallion. Half medallions along the upper and lower edges with quarter medallions at the corners and end borders enclosing clumps of flowers are also particular features.

The costumes and textiles of the frontier herding groups in Tharparkar are among the most powerful because of the symbiosis over many centuries of Muslim and Hindu social and religious traditions. Amongst these, the Muslims attach a great deal of importance in girls to appliqué, quilting and embroidery skills, which are in direct proportion to their desirability as wives and mothers. Conventional wisdom dictates that girls begin to accumulate and work on their dowries when very young as they should include a variety of clothing: several blouse-fronts, a skirt, storage bags, purses, dowry wraps, a quilt and as much jewellery as their fathers can afford.

Among the herdsmen who live close to the border with India and who earn their keep by selling supplies of milk and ghee (clarified butter used as a cooking medium or as artisans and laborers in neighboring and farms, the Rabaris are particularly well known for their spirited embroideries. The women's veils (odhani) and gathered skirts (gaghra) are black to symbolize a state of ritual mourning. Wool is most commonly used and is of a coarse handspun variety as it is the most cost-effective and readily available raw material. The woolen cloth may have a simple woven black-an-white chequer-board pattern, or it may be left plain or tie-dyed before it is embroidered. A distinctive Kutchi Rabari textile is the dark woolen ludi or odhani that girls embroider for their weddings. It has a tie-dyed pattern of red orange of yellow dots and is elaborately embroidered at both ends and along a central seam with scattered medallions of one of the vividly colored desert flowers of which the most popular is a bright-yellow mimosa (Acacia Arabica). With all Rabari motifs there is very little distinction between representation and abstraction. The stylized flowers, symbols of fertility, often have raised centers using triangular-shaped mirrors and white buttons as accents. The ends, often with a supplementary weft pattern, have dramatic embroideries of flowers and peacocks in square-chain, interlacing, herringbone, buttonhole and couched stitches. At the same time the bridegroom carries a brightly embroidered pothu or purse edged with colored felted-wool pompons as the travels with his family and friends to his bride's house, echoing the vibrant colors and embroidery in yellow, white, pink, orange, green and purple thread on her ludi.

Larh, the low-lying delta areas of the Indus, are home groups of Jat nomads, regarded as camel breeders of Scythian extraction and amongst the oldest inhabitants of Sindh. The women's costumes of the different groups share basic design elements or motifs that have identical names as they are commonly both drawn from nature and reflect the gradual transition from a nomadic to an agrarian way of life. Stylized forms of the sun, moon, stars, flowers, streams, rice grains, millet stalks and fields of crops are reduced and repeated to form ingenious minimalist patterns used in striking juxtapositions. Mirrors highlighting individual motifs can vary in size from tiny imperceptible dots to pear-shaped discs of up to 15 mm in diameter. The giichi is embroidered in a meticulous grid layout that covers the chest almost entirely. This linear arrangement is a distinctive feature of Jat embroidery. The sun is a predominant motif framed by rows of stylized flowers in narrow borders or columns containing mirrors. The embroidery is less dense than the pakkoh style of Tharparkar with combinations of square-chain, buttonhole, interlacing, satin and couched stitches using maroon, black, white and occasionally yellow-ochre silk or cotton thread. Symmetrically placed roundels embroidered in laid and couched stitches have triangular rays emanating from the centre. The edges of the gaj, the sleeves, the hem and the neckline together with its central opening are often fortified by a striking black cretan stitch, the gaano. Umrani Jat women often attach columns of tear-drop-shaped mirrors in bold red, black and white buttonhole stitches on to their yoke, with a scatter of floral motifs on their sleeves that reduce sequentially in size as they approach the cuffs. The cuffs of the sleeves end in a fixed combination of embroidered borders, kungri, tikko, dor, warho, and finally the gaano. The colors are used in a vibrant satrangi (seven colors) combination: red, green, orange, deep blue, white, yellow and black or purple. Although these gaj share a number of stitches with the pakkoh style and are essentially floral in theme, their edges are much more fluid and rounded. In addition to square-chain, double-buttonhole, herringbone, cretan and chain stitches, Romanian couching and a characteristic kharek (literally 'fruit of the date palm') stitch are commonly used. The kharek stitch is made up of arrow bars of satin stitch laid closely together in the form of triangles, V-shapes or small squares. Mirrors may be used as central highlights and when outlined with a couched stitch the kharek works effectively as an outlining or as a filling-in stitch; used in this way the bars of satin stitch are also known as nehran ('river').

Groups of Mahars, who like the Jats are pastoralists and cattle breeders, have taken to farming arable tracts around Sikarpur, Ghotki and along the Cholistan border. They combine exquisitely embroidered geometric and floral patterns with small mirrors (shishobhart). Mahar thalposh (ceremonial or dowry wraps), chadar (shawls) and bhujkis (purses) are immediately recognizable as the interlacing, double-buttonhole, square-chain, cross, couched and satin stitches are extraordinarily fine, and the curvilinear outlines seen in the gaj from further south are replaced by increasingly square and polygonal compositions or embroidery. The Sindhi cap (topi) from the Siro has the finest embroidery, using pat or silk thread with tiny mirrors. It has a flat crown and a soft, even rim with a dome-shaped cut-out over the forehead.

Areas of the Dadu district in the west of Sindh and the Katcho plain are inhabited by Sindhi Balock groups - the Khosas, Palaris, Jokhias, Burfati and Karmatis, who live on both sides of the Kirthar and Lakhi ranges. Their gaj embroideries consist of intricate geometric patterns in the soof style. Mirrors are not generally used and individual motifs are framed in vertical columns. Of particular interest are the Lohana women of farming groups in Thano Bula Khan who embroider stunning silk cholas, straight knee-length tunics so thickly encrusted with panels stiff. The cholas are wedding shirts, but similar densely structured embroidery using 'heaped' forms of double-buttonhole, square-chain and open-chain stitches are also used to embellish children's dresses caps, coverlets and animal adornments.

The ground fabric may be laid but in a similar fashion to kanbiri or in bands to form sequential rectangles but the stitches are combination of the certain, cross, double-running and back varieties. Rallis can be seen in the courtyards of shrines (dargahs) throughout Sindh today

Jute matting or old woolen blankets form the base of these exquisitely floor rugs or wall hangings. With the use of a special needle called "aar" the ground is completely covered with chain stitch embroidery, depicting scenes of hunting, wedding celebrations, rural life and floral or geometric patterns. The creation of training centres in Muzaffarabad and Kahuta has encouraged and given impetus to this craft.

KUNDI/EMBROIDERY ON LEATHER

Fine embroidery on leather known as kundi work was traditionally produced, especially for use on gun-belts and their accoutrements, in a broad 'frontier' area spanning parts of the Punjab, NWFP and Baluchistan. Dera Ghazi Khan, Dera Ismail Khan and Quetta were all known for this type of fine silk embroidery. Whatever the place of origin, embroidery of this type is almost always in patterns of small circles done in buttonhole and chain stitch, densely packed together on the leather ground.

PASHK OF MAKRAN

Pashk from the Makran coast employ a similar precise layout in their embroidery but a slightly different palette of colors, two shades of red (usually red and maroon), black, white, dark green and royal blue. A conspicuous border or frame (pat daman) made up of horizontal bands of colored stitches, surrounds the central pudo and may extend along the seams. This framing border varies from those of Khat and Khuzdar in the use of the jalar stitch, an elongated and elaborate form of the herringbone stitch (maipusht). In a number of pashk worn today, applied narrow braids have replaced a number of the supplementary borders.

PHULKARI EMBROIDERY

Perhaps the best known of all embroideries from the Punjab is the phulkari. Unlike the woven textiles, phulkari is essentially a domestic textile, made by a non-professional embroider in her home, for herself or for her own family. While some rich patrons might employ embroiders in their households to make fine phulkari, these were not traditionally items to be bought and sold in the bazaar, but given as gifts at auspicious event, especially weddings.

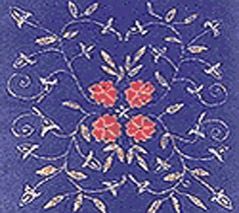

Made and used by both Muslim and Hindu communities, phulkari of either society differ to some degree: those made by Hindu embroiderers incorporated figurative designs of people, animals and household implements, while the Muslim communities confined themselves to non-figurative geometric patterns. Originally an art of rural communities, phulkari (which means flower work) were embroidered in floss silk thread (pat) on coarse hand woven cotton fabric (khaddar). This ground fabric was usually dyed with madder to a deep reddish-brown or sometimes an indigo blue and the embroidery was almost always in yellow or white. At its most basic level for everyday use, the embroidery would consist of simple flower shapes dotted over the fabric of the full skirts (ghaghra) or the large all-enveloping head-covers (chadar) traditionally worn by rural Punjabi women. More elaborate types called bagh (garden) also evolved for use as ceremonial gifts.

The most remarkable feature of the phulkari of that it is worked entirely from the reverse of the fabric, so that the embroiderer does not (or need not) see the front while she is creating the pattern. The rigid geometry of the bagh pattern is produced by counting the threads on the reverse of the ground fabric, which is fortunately of fairly coarse yarn and loose weave, before taking up a single thread with the needle, leaving a long 'float' of silk on the front.

Phulkari type embroidery from regions other than Punjab

Some of the finest embroidery of NWEP comes from the remote valleys of Indus Kohistan, especially the area between Patan and Kamila, where small settlements beside tributaries of the Indus - such as the Palas and Kolai Rivers - produce embroidered costume and small bags worked in minute cross stitch, surface darning stitch and tent stitch. The use of a phulkari-type stitch in this remote northern area is a reminder of the continuous and far-reaching movement that has traditionally taken place both within the Kohistan region itself and between Kohistan and the Punjab and Hazara districts.

In contrast of Indus Kohistan with its fondness for tiny cross-stitch designs, the Swat Valley and its lower-lying neighbor Hazara are traditionally associated with embroidery of the phulkari type. The Hazara pieces typically use a color scheme of dark pink on a white or dark-blue ground, in contrast to the yellow and orange of the Punjab, and the design elements themselves often have a 'feathered' effect on the outlines unlike the straight edges seen in the Punjab pieces. Hazara is also the source of another distinctive type of white ground shawl with pink and red designs in a markedly different style from the phulkari with curling horned and star patterns.

The Swat phulkaris may be embroidered from the front, unlike the Punjabi type in which the embroidery is always done from the back of the cloth, and the patterns may first be outlined with running stitch before being filled in with satin stitch. The women's shirts (kurta) that were once widely worn in Swat are embroidered with pink floss silk on dark-blue indigo-dyed cotton.

TILLA JOOTI/GOLD AND SILVER EMBROIDERY ON SHOES

Multan and Lahore, as well as the nearby town of Sharaqpur, are traditionally known for finely embroidered shoes (jooti or khussa). While jooti is a generic term for shoes of all traditional types, the khussa is the traditional round-toed slipper. When the toe is curled up to a fine point the shoe is called salimshahi, after the Mughal emperor Jahangir (formerly Prince Salim) who supposedly made them fashionable. Both types are frequently lavishly embroidered with gold or silver thread (tilla).

Embroidery of Pondicherry,

Ari embroidery of Tamil Nadu is done by both men and women, mainly in the Sri Perumbpadur area of Tamil Nadu. The craft was initially practised by the upper class trading community and later spread to members of other communities. The embroidery is done for the Real Madras Handkerchief as well as for saris and other clothing. The craft requires a frame of wooden beams with holes, fabric, a long needle, threads, tikris and beads. The work is home-based. The frames are of various sizes, usually about 1.5 feet high. The cloth is secured on the frame with a strong thin rope. The design is sketched on it with a stencil. Chalk is mixed with petrol to transfer the design onto the cloth. One hand is placed under the cloth holding the thread to the needle while the other hand moves the needle on top of the cloth with ease. Tikris and beads are attached to the cloth with the needle. This work done on the Real Madras Handkerchief is chiefly for export; this is a cloth measuring 36" by 36" and has a traditional market in Africa where Nigerian women wear them on ceremonial occasions. Another embroidery style is the jaali or net embroidery which resembles drawn threadwork and is done by pulling the warp and weft threads and fixing them with minute buttonhole stitches. The designs are in geometrical and floral shapes.

Ari embroidery of Tamil Nadu is done by both men and women, mainly in the Sri Perumbpadur area of Tamil Nadu. The craft was initially practised by the upper class trading community and later spread to members of other communities. The embroidery is done for the Real Madras Handkerchief as well as for saris and other clothing. The craft requires a frame of wooden beams with holes, fabric, a long needle, threads, tikris and beads. The work is home-based. The frames are of various sizes, usually about 1.5 feet high. The cloth is secured on the frame with a strong thin rope. The design is sketched on it with a stencil. Chalk is mixed with petrol to transfer the design onto the cloth. One hand is placed under the cloth holding the thread to the needle while the other hand moves the needle on top of the cloth with ease. Tikris and beads are attached to the cloth with the needle. This work done on the Real Madras Handkerchief is chiefly for export; this is a cloth measuring 36" by 36" and has a traditional market in Africa where Nigerian women wear them on ceremonial occasions. Another embroidery style is the jaali or net embroidery which resembles drawn threadwork and is done by pulling the warp and weft threads and fixing them with minute buttonhole stitches. The designs are in geometrical and floral shapes.

Embroidery of Sri Lanka,

The traditions of embroidery - the art of decorating a fabric with a thread and needle - in Sri Lanka are very similar to those of weaving: a particular kind of embroidery - remarkably Indian in style - was limited to the royal court and the aristocracy; the other category was an indigenous variety of embroidery.

The traditions of embroidery - the art of decorating a fabric with a thread and needle - in Sri Lanka are very similar to those of weaving: a particular kind of embroidery - remarkably Indian in style - was limited to the royal court and the aristocracy; the other category was an indigenous variety of embroidery.

TRADITIONS

The royal cloth-embroiderers embroidered garments only for the royalty; the other sacred duty they performed was to make the vestments, curtains, flags, etc., for the temples and viharas or mansions. They provided the pacca hettaya (brocade jacket) and the gold embroidered toppiya (square hat) for the Chieftain, and also embroidered jackets for his wife and daughters. The kind of materials used were mainly Indian in origin - red felt, velvet, tinsel, brocades for jackets and gold thread which was used in embroidering hats and ceremonial fans.

The indigenous variety of embroidery executed on home-made materials was mainly done by the dhobies or radav (washermen). This category of artisans usually embroidered cotton materials, Kandyan hats, decorations or reli-palama, cloths on special occasions, and utilitarian items like betel-bags, cotton jackets, and handkerchiefs.

STYLES

The embroidery practised in Kandy is quite distinct - in terms of designs, colours, and materials used - from the styles found in the other parts of the country. The base material is usually homespun, and the designs are in cotton thread, with silk thread worked in. This kind of embroidery is used to embellish handkerchiefs, napkins, and headgear with coloured borders and edges. Kandyan embroidery has a tradition of combining peasant colour schemes with classic traditions, whereby the colours selected for the embroidery was done according to the tastes of the locals with traditional Sinhalese motifs. Commonly used motifs include swans, lotuses, and peacocks. The embroidery is done with traditional hand-stitching, almost faultless in its execution.

EXAMPLES OF SINHALESE EMBROIDERY

Some of the most commonly embroidered items include: betel-bags or bulat-payi of all sizes, kerchiefs or napkins (lensu), caps or ispayya, jackets or hetta, pillow cases or kotta ura, pacisi cloths, (embroidery of a a race game done on chequered cloth) and saddle cloths or palasa. Betel bags vary in size from small ones carried in the waist-belt to very large ones, about four feet or more in length.

1. The Betel Bag

Traditionally, noblemen had attendants who carried their betel-bags and lime-boxes while travelling. Traditional betel-bags were oval shaped, made of blue cloth lined with undyed cotton - cloth which opened nearly half-way down the whole length at the sides - and with the inner part separated into two divisions. The inner division consisted of a double piece of cloth, which was also used as a pocket known as the hora payiya or hidden pocket; this had a very small opening at the upper end through which money, spices, and other valuables were put in. The larger items were always carried in the two outer pockets. The handle of the betel-bag was made of embroidered cloth or of a band of plaited cord and it ended with a beautiful and ingeniously worked hard-ball or vegedi-borale and a tassel or pohottuva. The outside of the bag was always beautifully embroidered on both sides in red and white cotton, using conventional designs.

In the actual construction of the embroidery there was always a centre design - floral or any other - framed by three or more borders parallel to the edge of the bag. The innermost border had the pala peti design (a lotus petal border, where depictions of lotus petals in their entirety alternate with petals three parts hidden by those on the side); the largest has the liya-vela design (this is a vegetable ornament design with a continuous stem of flowers and leaves with rhythmically disposed floral or foliar elements, also defined as a continuous scroll of foliage - single or double, large or small - and enclosing partially or throughout the figures of dancers); and the others had variations of the havadiya (this is a girdle design inspired form the silver girdle worn by the Kandyan women around their hips with a linked floral design or a continuous liked-herringbone kind of a design define) and the gal-binduwa (also called as gem dot, the design is inspired from a row of set gems used mainly as a border design) patterns. A limited amount of coloured silk was also used. Occasionally the bags were square in shape: these were made from a square piece of material with the four corners drawn together for the attachment of the handle having four cords.

2. Jackets

The jackets worn by the gavi-vamsa ladies (daughters and wives of Kandyan chiefs) were usually embroidered with floral or animal motifs in coloured and gold threads. The jackets were made mostly in silk. The use of brocade jackets and gold-embroidered square hats or toppiya by the aristocracy indicates the use of south Indian materials such as velvet and brocade. The dancers of Kandy and the wadiga patuna troupes in the southern regions of the country have always worn heavily embroidered velvet jackets decorated with corals and beads.

The jackets worn by the devil-dancers were also well-embroidered, either with thread in the same style as the betel-bags or using the technique of appliqué. One of the devil-costumes or gara-yakshaya had a red hand-made cotton cloth skirt and jacket with the skirt having three flounces. The jacket had fastenings behind. The entire jacket was covered with elaborate blue and white cotton appliqué embroidery where the edge of the applied cloth is turned in and sewn with white cotton. The chest design was braided where narrow strips of applied cloth were sewn down following the pattern. Appliqué-work was also found on flags and pillow cases. In this work, edges were always carefully turned and were bound by hemming or by a running stitch close to the edge or even a chain stitch.

3. Pillow Cases

Traditionally. pillow cases nearly always had a centre piece of blue cloth embroidered with a design having a border three or four inches wide with a patchwork of red, white, and blue squares of cotton cloth. Earlier, embroidery was used in place of the patchwork.

4. Saddle Cloths

Saddle cloths or palasa comprised of red cloths embroidered with white and blue cotton.

5. Caps

Embroidered caps, known as ispayya, had thinly quilted flaps; the cap itself was embroidered with fine coloured silks.

6. Kerchiefs, Napkins, Shawls

Embroidered kerchiefs, napkins, and shawls were usually made of cotton and occasionally linen. Fine-drawn thread work resembling lace was often found along with a fringe of needle-work lace. Some of these napkins had a characteristic style of embroidery in which the embroidery looked the same on both sides of the cloth. This effect was obtained by working even stitches equally in the back and front with spaces in between; the spaces were then filled up when going over the work a second time. The inspiration for such designs came from woven cloth. When the napkin was used as a covering for offerings it was known as pesa lensuva.

TYPES OF EMBROIDERY STITCHES USED

1. The Chain Stitch

Most Sinhalese embroidery work is done using the chain stitch. When the background is blue, the pattern is outlined in a white and red chain stitch, with the red inside and the white outside. The double outline in chain stitch is a very characteristic feature. When the borders of the betel-bag are done, they are separated from each other by three rows of chain stitch in red or blue between two white lines. The stitch is often made complex by intertwining red or blue threads or one thread of each colour.

2. The Binding Stitch

Binding stitches are characteristic; they are drawn quite flat for the sake of clarity. These stitches are sometimes strengthened and elaborated by intertwining a coloured thread along each side below the edge of the material.

3. The Herringbone Stitch

A complicated stitch, characteristic of Sinhalese embroidery, is the patteya (centipede) or mudum mesma (back-bone) stitch. This is basically an elaborate herringbone stitch. For this stitch, two needles are used together; sometimes even three colours are worked together. This stitch is most often used for binding the outer edges of large and small betel-bags.

4. The Buttonhole Stitch

Buttonhole stitches are used to depict conventional foliage that needs filling. This stitch - when done in a combination of two colours - gives a rich effect.

5. A Combination Stitch

A combination stitch that is commonly used consists of two kinds of stitches. It has two Y-shaped stitches held down by a stitch at the top and the bottom, forming a square. It is then filled in with satin stitch in a different colour. The satin stitch is used to fill in small squares and other spaces.

6. The Back Stitch

7. The Feather Stitch

This is used to fill in spaces.

8. Other Techniques

There are several other techniques also present in embroidery work. In one method the warp and weft threads are themselves used to create embroidery-patterns on the cloth where stitches are made on the ground-fabric using various combinations of the warp and the weft; an example would be the cross-stitch done on the matty cloth. Another method is to work out embroidery stitches on a pre-decided design drawn on the fabric.

The methods used in embroidery are drawn thread method where threads are removed from the warp and weft of the fabric using some kind of regular count to create a pattern and the other method is to use a stilette or a needle-like implement to pierce the cloth and make holes creating some patterns called as the borderic anglaise method. The third method in embroidery is the appliqué method where designs cut from a different fabric are applied onto the ground fabric to create unique embroidery- patterns. These methods have been in existence as part of the traditions of Sri Lanka since the seventeenth century.

In the modern examples of embroidery, examples of cross-stitch, cut work, renaissance work, hardagner work, fillet darning, quilting, and shadow work are present.

MOTIFS & DESIGNS

- The natural form of the motif of the snake (cobra) or naga has been in use since the mediaeval period as a decorative design in betel bags and other handicraft products.

- The liyawela motif - a composition of leaves, branches, flowers, buds, and tendrils, which trail from a sinuous creeper forming a symmetrical pattern - is also common. Sometimes two such creepers are drawn intertwined with unvarying uniformity to form a graceful design. This is normally found as a border design. Many of these compositions start from the central figure of the bird - either mythical or natural - from its mouth or tail. When two creepers are intertwined, the motif is known as dangara vel and when they are linked by some other method the design is called vel puttuwa. This motif and its variations are widely found in Sinhalese embroidery.

- Katuru mala or katiri mala is a floral motif with crossed petals resembling a pair of scissors. This does not resemble any natural flower form. The variation of vaka deka ( double curve) is widely used.

- The nelum mala or lotus flower is the most frequently occurring motif in Sinhalese craft. This is mainly seen as a geometric form within a circle. The petals number four, eight, 16, 32, or more, but always occur in multiples of four.

- The wel iruwa is a geometric design common in embroidery.

- The diyarella is a diagrammatic representation of a series of waves, rising and falling in a gentle breeze. This basic pattern has several elaborate variations. Ananda Coomaraswamy calls this design the chevron or a zig-zag pattern.

- Havadiya - also called weldangaraya or havadidangaraya - is a chain motif with different variations; it is seen to quite an extent in embroidery and a variation of this motif is found in appliqué work.

- Western influence is clearly visible in the use of rose as a motif in Sinhalese embroidery.

- Batticaloa district (on the eastern coast): hand-embroidery craft is found in the villages of Puthukudiyiruppu, Kallady, and Thalankudah.

- Badulla district: needlework and embroidery are found in the villages of Ella, Elawala, Bandarawela, Kendaketiya, Diyatalawa, Kappitipola, Haputale, Haliela, Badulla, Passara, and Mathiyangana.

- Colombo district: hand embroidery is found in the villages of Rajagiriya, Nugegoda, Pannipitiya, Maharagama, Dehiwala, Padukka, Kotte, Angoda, and Colombo town itself.

- Jaffna district (northern part of the island-country): hand-embroidery is found in Jaffna town.

- Kegalle district: hand-embroidery is found in the villages of Paragammana and Mirihella.

- Kurunegala district: hand-embroidery is found in the village of Alawwa.

- Ratnapura district: embroidery craft is practised in the village of Mulangama.

- Moneragala district: embroidery is found in the village of Wegama.

- Nuwara Eliya district (next to Kandy district, in the central part of the country): embroidery is practised in the villages of Pundaluoya, Ramboda, Maskeliya, Rikiligaskada, Kumbaloluwa, Ginigahtena, Nuwara Eliya town, and Hatton-Dikoya.

- Puttalam district (on the western coast ): hand-embroidery is found in the village of Nainamadama East.

- Trincomalee district (on the eastern coast): the craft is practised in Trincomalee town.

- Vavuniya district: embroidery is found in the village of Puthukudiyirrupu.

Embroidery of Tamil Nadu,

Ari embroidery of Tamil Nadu is done by both men and women, mainly in the Sri Perumbpadur area of Tamil Nadu. The craft was initially practised by the upper class trading community and later spread to members of other communities. The embroidery is done for the Real Madras Handkerchief as well as for saris and other clothing. The craft requires a frame of wooden beams with holes, fabric, a long needle, threads, tikris and beads. The work is home-based. The frames are of various sizes, usually about 1.5 feet high. The cloth is secured on the frame with a strong thin rope. The design is sketched on it with a stencil. Chalk is mixed with petrol to transfer the design onto the cloth. One hand is placed under the cloth holding the thread to the needle while the other hand moves the needle on top of the cloth with ease. Tikris and beads are attached to the cloth with the needle. This work done on the Real Madras Handkerchief is chiefly for export; this is a cloth measuring 36" by 36" and has a traditional market in Africa where Nigerian women wear them on ceremonial occasions. Another embroidery style is the jaali or net embroidery which resembles drawn threadwork and is done by pulling the warp and weft threads and fixing them with minute buttonhole stitches. The designs are in geometrical and floral shapes.

Ari embroidery of Tamil Nadu is done by both men and women, mainly in the Sri Perumbpadur area of Tamil Nadu. The craft was initially practised by the upper class trading community and later spread to members of other communities. The embroidery is done for the Real Madras Handkerchief as well as for saris and other clothing. The craft requires a frame of wooden beams with holes, fabric, a long needle, threads, tikris and beads. The work is home-based. The frames are of various sizes, usually about 1.5 feet high. The cloth is secured on the frame with a strong thin rope. The design is sketched on it with a stencil. Chalk is mixed with petrol to transfer the design onto the cloth. One hand is placed under the cloth holding the thread to the needle while the other hand moves the needle on top of the cloth with ease. Tikris and beads are attached to the cloth with the needle. This work done on the Real Madras Handkerchief is chiefly for export; this is a cloth measuring 36" by 36" and has a traditional market in Africa where Nigerian women wear them on ceremonial occasions. Another embroidery style is the jaali or net embroidery which resembles drawn threadwork and is done by pulling the warp and weft threads and fixing them with minute buttonhole stitches. The designs are in geometrical and floral shapes.

Embroidery of Uttarakhand,

Embroidery is defined as the handicraft of decorating fabric or other materials with needle and thread or yarn; or embellishment with fanciful details. Embroidery of Uttarakhand is famous because of the versatility of creations by the craftspersons. To decorate the items, the artisans use a selection of stitches. The craft of embroidery serves as one of the main sources of income for many communities of this region. Despite being a traditional craft of decorating clothes, it is still relevant and popular. In Uttarakhand in the Bageshwar district a group of artisans defined as the Mandalsera Cluster practice this craft. The designs may be traditional or modern day geometric patterns, embroidery continues to be one of the common ways of decorating clothes. The embroidery is done on a wooden frame, to secure the cloth. These frames may vary in size. The fabric is decorated with the help of a long needle, threads, tikris and beads. Another embroidery pattern is the jaali or the net embroidery in geometric or floral shapes. This is done by pulling the warp and weft threads and fixing them with minute buttonhole stitches. The products are made predominantly for household use like curtains, bedspreads, furniture covers and dress material.

Embroidery is defined as the handicraft of decorating fabric or other materials with needle and thread or yarn; or embellishment with fanciful details. Embroidery of Uttarakhand is famous because of the versatility of creations by the craftspersons. To decorate the items, the artisans use a selection of stitches. The craft of embroidery serves as one of the main sources of income for many communities of this region. Despite being a traditional craft of decorating clothes, it is still relevant and popular. In Uttarakhand in the Bageshwar district a group of artisans defined as the Mandalsera Cluster practice this craft. The designs may be traditional or modern day geometric patterns, embroidery continues to be one of the common ways of decorating clothes. The embroidery is done on a wooden frame, to secure the cloth. These frames may vary in size. The fabric is decorated with the help of a long needle, threads, tikris and beads. Another embroidery pattern is the jaali or the net embroidery in geometric or floral shapes. This is done by pulling the warp and weft threads and fixing them with minute buttonhole stitches. The products are made predominantly for household use like curtains, bedspreads, furniture covers and dress material.

Embroidery of West Bengal,

The chief types of embroidery in West Bengal are the kantha with folk motifs, the chikan, zari work, and kashida. Chikan embroidery is fine and delicate and done on muslin or cotton cloth of a fine texture. The decoration is linear in appearance and done with light-coloured thread. Blue thread embroidery is done on still lighter blue and white embroidery is done on white cloth. White on white is the most popular combination. Kashida or silk embroidery on cotton is not very common nowadays and is restricted to prayer caps and head scarves for Muslim. Modern embroidery is more contemporary in style, with a mixture of alpana designs, kathiawari mirror work, and Kashmiri stitches. Cross stitch and cutout work are also seen, usually on table linen.

The chief types of embroidery in West Bengal are the kantha with folk motifs, the chikan, zari work, and kashida. Chikan embroidery is fine and delicate and done on muslin or cotton cloth of a fine texture. The decoration is linear in appearance and done with light-coloured thread. Blue thread embroidery is done on still lighter blue and white embroidery is done on white cloth. White on white is the most popular combination. Kashida or silk embroidery on cotton is not very common nowadays and is restricted to prayer caps and head scarves for Muslim. Modern embroidery is more contemporary in style, with a mixture of alpana designs, kathiawari mirror work, and Kashmiri stitches. Cross stitch and cutout work are also seen, usually on table linen.

Engraving and Calligraphy on Rice Grains of Andhra Pradesh/Telangana,

Micro-calligraphy and painting on rice grain(s) is an old Indian tradition. This craft requires immense concentration, neatness of hand, and keen eyesight. The engraved rice grain is usually enclosed in a key chain, pendant, or bracelet, thus keeping it safe, and combining it with a utilitarian function.

Micro-calligraphy and painting on rice grain(s) is an old Indian tradition. This craft requires immense concentration, neatness of hand, and keen eyesight. The engraved rice grain is usually enclosed in a key chain, pendant, or bracelet, thus keeping it safe, and combining it with a utilitarian function.

Engraving and Calligraphy on Rice Grains of Delhi,

Micro-calligraphy and painting on rice grain(s) is an old Indian tradition. This craft requires immense concentration, neatness of hand, and keen eyesight. The engraved rice grain is usually enclosed in a key chain, pendant, or bracelet, thus keeping it safe, and combining it with a utilitarian function.

Micro-calligraphy and painting on rice grain(s) is an old Indian tradition. This craft requires immense concentration, neatness of hand, and keen eyesight. The engraved rice grain is usually enclosed in a key chain, pendant, or bracelet, thus keeping it safe, and combining it with a utilitarian function.

Engraving and Calligraphy on Rice Grains of Tamil Nadu,

Micro-calligraphy and painting on rice grain(s) is an old Indian tradition. This craft requires immense concentration, neatness of hand, and keen eyesight. The engraved rice grain is usually enclosed in a key chain, pendant, or bracelet, thus keeping it safe, and combining it with a utilitarian function.

Micro-calligraphy and painting on rice grain(s) is an old Indian tradition. This craft requires immense concentration, neatness of hand, and keen eyesight. The engraved rice grain is usually enclosed in a key chain, pendant, or bracelet, thus keeping it safe, and combining it with a utilitarian function.

Engraving and Calligraphy on Rice Grains of Uttar Pradesh,

Micro-calligraphy and painting on rice grain(s) is an old Indian tradition. This craft requires immense concentration, neatness of hand, and keen eyesight. The engraved rice grain is usually enclosed in a key chain, pendant, or bracelet, thus keeping it safe, and combining it with a utilitarian function.

Micro-calligraphy and painting on rice grain(s) is an old Indian tradition. This craft requires immense concentration, neatness of hand, and keen eyesight. The engraved rice grain is usually enclosed in a key chain, pendant, or bracelet, thus keeping it safe, and combining it with a utilitarian function.