Hand Block Printing of Punjab,

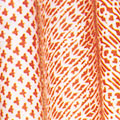

The local phulkari embroidery has inspired bold floral and geometrical designs, found on wraps and stoles. Due to commercial reasons, however, the focus has shifted to screen printing.

The local phulkari embroidery has inspired bold floral and geometrical designs, found on wraps and stoles. Due to commercial reasons, however, the focus has shifted to screen printing.

Hand Block Printing of Sanganer, Rajasthan,

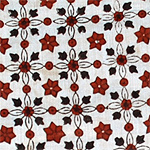

Sanganer, near Jaipur, is famous for its hand-block designs and techniques. Gold and silver colours are also used in printing. The links with the paintings of bygone eras is visible from motifs like stylised sunflowers, narcissuses, roses, and other flowers of luxuriant foliage like daturas, rudrakshas, and arkas.

Sanganer, near Jaipur, is famous for its hand-block designs and techniques. Gold and silver colours are also used in printing. The links with the paintings of bygone eras is visible from motifs like stylised sunflowers, narcissuses, roses, and other flowers of luxuriant foliage like daturas, rudrakshas, and arkas.

Hand Block Printing of Udaipur, Rajasthan,

In Udaipur and Nathdwara the block prints are on saris, wraps, and quilt covers. The designs are religious in nature and are linked with Srinathji, a part of the Pichwai tradition. The prints on the cloth are done with sandal wood blocks which leave a perfume in the cloth. The main technique involves placing the block directly on the fabric for the design-transfer to be effected.

In Udaipur and Nathdwara the block prints are on saris, wraps, and quilt covers. The designs are religious in nature and are linked with Srinathji, a part of the Pichwai tradition. The prints on the cloth are done with sandal wood blocks which leave a perfume in the cloth. The main technique involves placing the block directly on the fabric for the design-transfer to be effected.

Hand Block Printing of Uttar Pradesh,

Uttar Pradesh is an important centre for hand-block printing with the classical butis, paisley designs, and the tree of life as the main traditional motifs used in a range of shapes and in bold, medium, and fine patterns. Inspired by Muslim architecture, the tree of life motif carries an Indo-Persian influence. It has floral designs and bouquets in panels in crimson, rose, matte brown, soft yellow, blue, and green set against arches shaped like mihrabs, along with symmetrical trees and jali designs bordered with calligraphy and inlay design. A lot of paisley motifs can be seen in the hand block printed fabrics of Lucknow, while the chikan embroidery motifs are more popular in other printing centres of Uttar Pradesh. Jehangirabad, another printing centre, is known toned down colours and bold lines in the Indo-Persian tradition. Tanda in Uttar Pradesh is famous for its detailed printing. The main colours used are red and a dark blue blended with red against an indigo background.

Uttar Pradesh is an important centre for hand-block printing with the classical butis, paisley designs, and the tree of life as the main traditional motifs used in a range of shapes and in bold, medium, and fine patterns. Inspired by Muslim architecture, the tree of life motif carries an Indo-Persian influence. It has floral designs and bouquets in panels in crimson, rose, matte brown, soft yellow, blue, and green set against arches shaped like mihrabs, along with symmetrical trees and jali designs bordered with calligraphy and inlay design. A lot of paisley motifs can be seen in the hand block printed fabrics of Lucknow, while the chikan embroidery motifs are more popular in other printing centres of Uttar Pradesh. Jehangirabad, another printing centre, is known toned down colours and bold lines in the Indo-Persian tradition. Tanda in Uttar Pradesh is famous for its detailed printing. The main colours used are red and a dark blue blended with red against an indigo background.

Hand Block Printing on Textiles of Nepal,

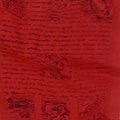

The tradition of using wooden blocks to hand print saris and other textiles in Nepal is an ancient one; however, with the increasingly large scale import of silk and synthetic saris it is in serious danger of dying out. Hand-block printing by the ranjitkar, the specific Newar hereditary caste of block printers and dyers, has a long tradition in the Kathmandu Valley. Hand-blocked saris, once greatly in demand, are rarely worn now; however, hand-printed shawls, blouses, jackets, and waistbands are still popular. Unfortunately, the white cotton cloth with the distinctive black and red block-print patterns has now to compete with cheaper, imported copies.

The tradition of using wooden blocks to hand print saris and other textiles in Nepal is an ancient one; however, with the increasingly large scale import of silk and synthetic saris it is in serious danger of dying out. Hand-block printing by the ranjitkar, the specific Newar hereditary caste of block printers and dyers, has a long tradition in the Kathmandu Valley. Hand-blocked saris, once greatly in demand, are rarely worn now; however, hand-printed shawls, blouses, jackets, and waistbands are still popular. Unfortunately, the white cotton cloth with the distinctive black and red block-print patterns has now to compete with cheaper, imported copies.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

The very basis of the ranjitkars' craft are the carved wooden blocks used during the process of printing. Each printer has a wide variety of carved blocks of varied patterns. These blocks are made of seasoned dar wood - this wood does not warp or bend even when moist. Soft wood is also used in Nepal to make wood blocks. The dimensions of the wooden block, on an average, are 18 x 13 cm; the blocks are fitted with a handle.

The cloth used for printing are of the following varieties: nainsut, markin, malmal, khaddar, and dambarkumari (a variety of cloth that is mostly used by women). Blouses, saris, belt cloths (patuka), etc. are made out of dambarkumari cloth which is somewhat finer than khaddar. The gunyu and cholo traditionally given to young girls are usually made of gawun cloth - this is full of designs, with a red, blue, or black background. Gawun cloth is a favourite with women in the hilly areas. They wear khaddar or dambarkumari saris in their daily life, while the gawun sari is carefully preserved for festive occasions.

The first step is to remove the starch used during the process of sizing the cloth. This starchy matter needs to be thoroughly removed with a good wash so that the cloth is ready to accept the colour dyes. The cloth is then folded and placed on a wooden anvil (dashi) and pounded with a wooden hammer. The hammer - made of a heavy wood called chilaune - is about 12 inches in length and is 5"-6" in circumference. After pounding, the cloth is completely smoothened and ready for printing.

Three to four layers of jute are evenly placed on the printing table, and covered with a woollen spread. This padding allows for an even spread of colour and print on the fabric. The block receives the dye from the dye (pa) box. This box, made of wood, in a size of about 10" x 8" x 1.5", is layered with jute and is covered with a fine soft cotton sheet, colloquially called astar. The purpose of this astar is to make the wooden block receive only the correct amount of dye. After the ranjitkar has poured the required amount of dye into the pa box he is ready to start printing. Traditional ranjitkars who, for centuries, used natural dyes that they made themselves, have now begun to use imported dyes and colours.

The fabric for printing is spread tight on the jute and woollen layers on the wooden table. The ranjitkar gently presses the wooden block on the pa box, and then applies - with even weight - the block on to the cloth. In this manner, the design is and printed on the plain cloth. An experienced printer can print about 15-20 saris, each 8 m, in one day.

The dot and line patterned design is made by the Newar chippahs settled in east Nepal. To print five 40 x 80 cm cotton lengths, the chippah firstly prepares a black dye from 200 g of mustard seed powder, 200 g of millet flour, and 1,000 g of iron dust. These are put into a clay jar, covered with water and stirred once a week for two to three 2 to 3 weeks. A second liquid is prepared by immersing the leaves of asuro (Adhatoda vasica) in water in a clay jar for a week to become a yellow juice. The cotton cloth is soaked in water, rubbed with crushed myrobalan paste, then dried, folded, and beaten. The wood block with the carved out dot/line pattern is printed with the first mixture, giving the black background. The second block, with stripes wide enough to cover the dot pattern, is printed over the dot pattern with a mixture prepared from one of the yellowish asuro liquid into which 20 gm of mineral salt (khar) is mixed. When it starts to effervesce, two to three drops of mustard oil are added. The printed cloth is dried in the sun before it is submerged in a madder dye (powdered madder plus water) and simmered for 5-10 minutes, resulting in black/brown background, red/brown background, red/brown lines, and white dots (which have been prevented from accepting colour by the asuro liquid). Today the cloth is worn mostly by the older generation of Limbu and Rai.

SYMBOLS & MOTIFS

The motifs and patterns used draw inspiration from well-known and symbolic objects. Printing patterns are numerous and are generally referred to as butta, a floral motif - these include fish motifs, stars, flowers, lines, and dots and a rich combination of small geometric patterns, often arranged diagonally. Each characteristic and easily recoginisable pattern and print has its own lyrical name individually assigned to it, like chilpa, butwali, mujia, dhakka, and dambarkumari. The prints, patterns, and colours used are specific and characteristic of the community that does them, thereby making the wearer instantly recoginisable. In the same way that the black sari of Lalitpur identifies the Jyapuni women agriculturalists, so the chippa sari instantly identifies the women of the hill regions. Traditionally Nepalese parents offer saris and blouses called gunyu and cholo to their daughters between the age of 7 and 11, or before they reach puberty.

DEVELOPMENTS

A relatively new development is the use of locally produced lokta bark paper, printed with the block prints of Nepali, Tibetan, and Chinese deities. They are sold as pictures or are sold as calendars, cards, and lanterns.

Hand Block Printing/Ajrakh of Gujarat,

Famous worldwide, the Ajrakh textiles of Kutch in Gujarat standout for their richly printed surface and elaborate crafting procedures. The printing is done on both sides in the shades of indigo and madder multiple dyeing techniques besides mordanting are employed. Natural vegetable and mineral colors are used to dye and print the fabrics. Items such as turbans, shawls, lungis, odhani, curtains, floor spreads and bed covers etc are created using these skilled techniques. Tools such as wooden printing blocks, colors, furnace, bamboo lattice, earthen dying vats, copper vessels for dyes, wooden battens, brushes etc are used for the crafting purpose. The Ajrak resist-printing technique is found in Anjar and Dhamadka in Kutch. The painted Ajrak cloth has colours - blue, red, black and white, in several patterns --- resembling those found at Fostat. The printed red and block odhnis of Anjar carry motifs similar to those found on old pottery and stone carvings.

The Ajrak resist-printing technique is found in Anjar and Dhamadka in Kutch. The painted Ajrak cloth has colours - blue, red, black and white, in several patterns --- resembling those found at Fostat. The printed red and block odhnis of Anjar carry motifs similar to those found on old pottery and stone carvings.

Famous worldwide, the Ajrakh textiles of Kutch in Gujarat standout for their richly printed surface and elaborate crafting procedures. The printing is done on both sides in the shades of indigo and madder multiple dyeing techniques besides mordanting are employed. Natural vegetable and mineral colors are used to dye and print the fabrics. Items such as turbans, shawls, lungis, odhani, curtains, floor spreads and bed covers etc are created using these skilled techniques. Tools such as wooden printing blocks, colors, furnace, bamboo lattice, earthen dying vats, copper vessels for dyes, wooden battens, brushes etc are used for the crafting purpose.

The Ajrak resist-printing technique is found in Anjar and Dhamadka in Kutch. The painted Ajrak cloth has colours - blue, red, black and white, in several patterns --- resembling those found at Fostat. The printed red and block odhnis of Anjar carry motifs similar to those found on old pottery and stone carvings.

The Ajrak resist-printing technique is found in Anjar and Dhamadka in Kutch. The painted Ajrak cloth has colours - blue, red, black and white, in several patterns --- resembling those found at Fostat. The printed red and block odhnis of Anjar carry motifs similar to those found on old pottery and stone carvings.

Hand Block Printing/Ajrakh of Rajasthan,

In Rajasthan, there are sandy stretches of desert where a unique method of cloth-dyeing prevails. The technique is called Ajrakh and the print is in dark shades of blue and red with geometrical patterns on both sides of the fabric. The technique is a complicated one and the steps include preparatory washing, application of mordant, resist printing, de-gumming, and dyeing. The resist substances used are gach (a mud resist) and kariyana, which is a mixture of the gum of the babul tree and chuna or lime. The lime provides a smooth texture and prevents the resist from cracking. After the final dyeing the cloth is sun-dried. It is dipped every night in a cow-dung solution and kept under a stone all night. Washing is done the next morning in the river and the drying is done on the sand. When half-dry, water is sprinkled on the cloth continuously. On the third day, the cloth is finally washed in the river, brought to the work-place and dried.

In Rajasthan, there are sandy stretches of desert where a unique method of cloth-dyeing prevails. The technique is called Ajrakh and the print is in dark shades of blue and red with geometrical patterns on both sides of the fabric. The technique is a complicated one and the steps include preparatory washing, application of mordant, resist printing, de-gumming, and dyeing. The resist substances used are gach (a mud resist) and kariyana, which is a mixture of the gum of the babul tree and chuna or lime. The lime provides a smooth texture and prevents the resist from cracking. After the final dyeing the cloth is sun-dried. It is dipped every night in a cow-dung solution and kept under a stone all night. Washing is done the next morning in the river and the drying is done on the sand. When half-dry, water is sprinkled on the cloth continuously. On the third day, the cloth is finally washed in the river, brought to the work-place and dried.

Hand Block Printing/Nandana of Madhya Pradesh,

One of the most famous motifs used here is the amba butti mango motif. In this centre, wax resist, block printing, and indigo vats are still used. The blocks are carved up to 10 cm in depth and can carry enough wax solution for a number of imprints. The motif range found here is limited but the designs are original and dramatic.

One of the most famous motifs used here is the amba butti mango motif. In this centre, wax resist, block printing, and indigo vats are still used. The blocks are carved up to 10 cm in depth and can carry enough wax solution for a number of imprints. The motif range found here is limited but the designs are original and dramatic.

Hand Block Printing/Resist/Dabu of Rajasthan,

The Resist/Dabu technique used here involves using wax or gum clay mixed with resin. This is applied with a brush or block, or by hand to portions of the cloth and the colour is applied subsequently. The wax is then washed off in hot or flowing water and the applied colour moves into this area to give a diffused effect. Block printing is done on the portion of the cloth where the original colour is retained. Specific outlines and patterns are highlighted against the contrast colour. The design gets a broken appearance like batik due to the leakage of colour once the resist is washed off.

The Resist/Dabu technique used here involves using wax or gum clay mixed with resin. This is applied with a brush or block, or by hand to portions of the cloth and the colour is applied subsequently. The wax is then washed off in hot or flowing water and the applied colour moves into this area to give a diffused effect. Block printing is done on the portion of the cloth where the original colour is retained. Specific outlines and patterns are highlighted against the contrast colour. The design gets a broken appearance like batik due to the leakage of colour once the resist is washed off.

Hand Screen Printing of Haryana,

Hand screen printing is a common technique that has been carried out for years in the textile pockets of the country. It is essentially a stencil process. An open mesh fabric is used to hold in place the 'islands' of the stencil design through which inks are forced using a flexible blade of rubber or polyurethane called a squeegee.

Hand screen printing is a common technique that has been carried out for years in the textile pockets of the country. It is essentially a stencil process. An open mesh fabric is used to hold in place the 'islands' of the stencil design through which inks are forced using a flexible blade of rubber or polyurethane called a squeegee.

Hand-block Printing of Prayer Flags of Nepal,

Any picture of Nepal is incomplete without a view of prayer flags that flutter from rooftops all over. It is believed that prayers are carried along the wind, and in Nepal and Tibet the prayer flag is known as the Windhorse or Lung Ta.

Any picture of Nepal is incomplete without a view of prayer flags that flutter from rooftops all over. It is believed that prayers are carried along the wind, and in Nepal and Tibet the prayer flag is known as the Windhorse or Lung Ta.

HISTORY & ORIGIN

While there is no scholarly consensus on the origin of prayer flags, it appears that they pre-date Buddhism. It is most likely that they originated in the Himalayas, in Tibet, with the Bonpo culture. The Dalai Lama has said that when Buddhism travelled from India to Tibet, the Tibetan Buddhists assimilated the prayer flag tradition. The Bonpo prayer flags, 2,500 years ago, bore this message: 'May the horse of good fortune run fast and increase the power of life, influence, fortune, wealth and health.

PROCESS & FORMATS

Skilled wood-block carvers, usually monks or lamas in Nepal and Tibet, carve the wooden hand-blocks required to print the prayer flags, as a form of spiritual practice. Squares of cloth, in each of the Five Elements/ Five Buddha Families colours, are printed in a single colour, usually black, and sewn on a cord in groups of five as each rolled set comprises a minimum of five flags. The sets of colours are repeated in multiples of five.

There are several styles of flag sets: they may be horizontal (Lung ta) or vertical (Dar cho) flag sets.

MOTIFS & IMAGES

The designs are reproduced on the prayer flags through hand blocks; the printing ink used is black in colour. The images on the prayer flags may be of the Buddha, the bodhisattvas, the Goddess Tara, or the Rimpoches; animals, and the lotus are also important motifs. The eight auspicious symbols that appear on many of the sets are the: the two fish, conch shell, parasol, furled banner, the Wheel of Teaching that the Buddha turned, the Eternal Knot, the lotus, and the Treasure Vase of Sacred Water filled with the nectar of immortality. Usually the symbol of the Wind Horse appears at the centre with the Wish Fulfilling Jewel on its back. On the corners are printed the four supernatural creatures of Buddhism: the garuda, the dragon, the tiger, and the snow lion. Sacred mantras accompany the images and add their weight to the message(s) being borne on the winds.

TRADITIONS & USES

These prayer flags are raised to mark auspicious occasions, particularly the New Year or lo sar, the Tibetan New Year, which normally falls in mid- to late February. Prayer flags are believed to be activated by the wind that moves them. In this, they function in a similar way to the prayer wheels. It is common to write a person's name or the birth or wedding date of a person on one of the prayer flags to personalise it. As the wind carries the prayers off the cloth and into the heavens, the blessings are released to assist those who hang the flags and to benefit all beings.

It is considered a sign of respect to keep the prayer flags off the ground and to have clear, beneficial intentions as they are being hung. As the cloth frays and the printed images fade and are worn out, they are often burned, to release the last expression of prayer. It is also common in Nepal to see old, tattered flags side by side with new ones, left to the elements.

Hand-knit Woollen Products,

Nepal has a wide variety of wool-bearing animals - its weather makes woollen products an integral part of everyday life. Today, high quality wool from sheep and the angora rabbit, as well as imported wool from New Zealand, are used to make sweaters, jackets, hats, caps, gloves, and mittens. Designs are based on both traditional Nepalese motifs, as well as on western motifs; the products are available in a wide range of colours.

Nepal has a wide variety of wool-bearing animals - its weather makes woollen products an integral part of everyday life. Today, high quality wool from sheep and the angora rabbit, as well as imported wool from New Zealand, are used to make sweaters, jackets, hats, caps, gloves, and mittens. Designs are based on both traditional Nepalese motifs, as well as on western motifs; the products are available in a wide range of colours.

The imported wool is first machine carded and then spun by hand. The traders and exporters of hand-knitted products give bulk orders to the entrepreneurs or thekedars (intermediaries) who in turn purchase wool from wool traders located mostly in Chhetrapati near Thamel. An individual thekedar distributes the knitting jobs to 20 to 30 home-based women workers and the finished knitted products are then collected from the women workers and supplied to the traders and exporters.

DEVELOPMENTS

Angora wool farming and production of angora wool products is a relatively recent development in Nepal where the environment has proved to be conducive to successful breeding of the angora rabbit. As in any new venture, there have been innumerable technical problems, due mainly to spinning defects. However strenuous efforts are being made to overcome these problems. Efforts are being made to upgrade the spinning process by blending angora wool with other wool, like pashmina and sheep's wool, and thereby ensure an upgradation in this project

LOCATION

Catering largely for the tourist and export trade, women - based at home - are employed in knitting work in areas like Thamel, Sankhu, Bhaktapur, Jorpati, Gokarna, Harisiddhi, Thimi, Lubhu, Chapagaon, Dallu, Swoyambhu, Kirtipur, and Banepa.

Hand-spinning of Ladakh,

Products ranging from pile rugs, garments, footwear, yarn, shawls, blankets, saddlebag, slings, rugs and tents are handcrafted under this craft. Tools required for the process are phang-spindle used by women, haa- spindle used by men, hand cards, tal- special comb etc.

Products ranging from pile rugs, garments, footwear, yarn, shawls, blankets, saddlebag, slings, rugs and tents are handcrafted under this craft. Tools required for the process are phang-spindle used by women, haa- spindle used by men, hand cards, tal- special comb etc.

Handloom Weaving,

The age-old craft of weaving was prevalent all over the Kandyan region in ancient times; nowadays it is practised mainly at Talagune, Uda Dumbara, and at Vellassa, all in the central province of the country; encouragement from the government - through the Department of Small Industries, State Trading Corporation (Salusala) and the Department of Textile Industries - has, however, increased the proliferation of weaving-centres. The handloom sector consists of small units, under the mixed purview of the private, corporate, and public sectors. With the removal of import restrictions, the handloom sector in Sri Lanka initially buckled under competition. Special impetus given by the government, especially technological inputs, the upgradation of technology with foreign assistance, and the enhancement of local skills through several workshops and seminars for the weavers have helped the craft (and the sector) find its feet again. One of the key training centres is the National Handlooms Centre (NHC), a specialised unit of the Textiles Ministry: this offers training in textile design, critical if Sri Lankan weavers are to compete successfully with international products available in the national market, as well as in the international market. Traditional 'dumbara weaving' is still practised in a few Kandyan villages such as Talagune, Dumbara in the Central Province of Sri Lanka. This is a truly indigenous form of folk weaving using cheap yarn that is created on a simple loom known as the 'pit loom'. These were/are inexpensive and are practical woven pieces - meant for the use of the peasants, with designs and patterns drawn from indigenous traditions.

The age-old craft of weaving was prevalent all over the Kandyan region in ancient times; nowadays it is practised mainly at Talagune, Uda Dumbara, and at Vellassa, all in the central province of the country; encouragement from the government - through the Department of Small Industries, State Trading Corporation (Salusala) and the Department of Textile Industries - has, however, increased the proliferation of weaving-centres. The handloom sector consists of small units, under the mixed purview of the private, corporate, and public sectors. With the removal of import restrictions, the handloom sector in Sri Lanka initially buckled under competition. Special impetus given by the government, especially technological inputs, the upgradation of technology with foreign assistance, and the enhancement of local skills through several workshops and seminars for the weavers have helped the craft (and the sector) find its feet again. One of the key training centres is the National Handlooms Centre (NHC), a specialised unit of the Textiles Ministry: this offers training in textile design, critical if Sri Lankan weavers are to compete successfully with international products available in the national market, as well as in the international market. Traditional 'dumbara weaving' is still practised in a few Kandyan villages such as Talagune, Dumbara in the Central Province of Sri Lanka. This is a truly indigenous form of folk weaving using cheap yarn that is created on a simple loom known as the 'pit loom'. These were/are inexpensive and are practical woven pieces - meant for the use of the peasants, with designs and patterns drawn from indigenous traditions.

HISTORY & TRADITION

Sri Lanka has always been a predominantly Buddhist nation, and among the practices associated with religion and religious leaders, is that of kathina robes worn by Buddhist priests. A particularly sacred and meritorious act was the presentation to the sangha or the order of the Buddhist priests a set of kathina robes spun, woven, and made up in a single day on the occasion of the close of vas or the Buddhist Lent. Kings and other members of royalty also performed this ceremony, 'employing hundreds of thousands of persons in jobs like picking cotton, weighing it, converting it into balls, spinning, weaving, washing, cutting into pieces, stitching, dyeing (from the treatise Rupavaliya, trans., p.48).

It has been recorded that King Parakrama Bahu II offered no less than 80 such robes to the priesthood, in memory of the 80 chief disciples of the Buddha. 'The learned king gathered together the inhabitants of Lanka - a great multitude of men and women - and set them all to work to prepare the cotton and other essentials and speedily finished the work of the robes. And he caused the eighty kathina robes to be given in the course of a single day.' (From the treatise Mahavamsa, Ch. LXXXV.) The king continued this practice on many other occasions. He was not alone in this - several other members in society obtained merit in the same way. On many such occasions, the ladies of the household lent a hand in the spinning of the yarn; the women were, however, not involved in weaving.

The cloth makers have been famed for making elaborate canopies to cover relic caskets and to provide shade for royalty during processions. Some of them were about 45 feet x 20 feet in size. All these are being preserved in the Buddhist temples, which have become repositories of documents and gifts of valuable collections of textiles over time.

THE BERAVAYO & THE SALAGAMAYO

Traditionally, weavers in Sri Lanka have been divided into two groups: the beravayo, indigenous weavers who were also musicians and astrologers; and the salagamayo who migrated from the south of India and were famed for their fine gold-woven cloths. It is narrated that during the rule of Vijaya Bahu III of Dambedeniya, an emissary sent to south India by him brought back eight master weavers; these eight weavers laid the foundation for the salagamayo in Sri Lanka. Owing to their falling into disfavour with Kandyan kings at a later date, the salagamayo were compelled to move from the interiors of the country and settle down along the south-western coast.

While the beravayo weavers have, from time immemorial, made plain hand-spun cottons characteristic of the Kandyan region, remaining unaffected by changes in fashion or the influence of Indian weavers, the salagamayo wove fabrics of a better quality and were engaged mainly in clothing royalty and others of high rank with their fine gold-woven material. Some form of social distinction thus evolved, wherein the salagamayo were considered to be superior to the indigenous weavers engaged in creating garments for the community at large.

Weaving was never the primary profession of indigenous weavers, who were chiefly musicians who played according to feudal customs on state occasions and during the Kandyan Pageant in honour of the Temple of the Tooth Relic or Perahera. They engaged themselves in weaving only in their leisure time to meet personal needs. They bartered some of their woven creations to obtain other items; their most elaborate woven creations were offered to temples.

RAW MATERIALS, PROCESS & TECHNIQUES

Cotton is mainly grown in the Hen or Chenas or the dry fields of the Kandyan region. The yarn is of two types - the large long-lasting variety and the dwarf annual variety called bala kapu. Cotton from the Kapok tree is used unbleached in the textile-production process. The cotton so picked is not spun in the field; it is taken home and dried and cleaned in large quantities. It is freed from the seeds by passing it through the rollers of the kapu kapana yantraya, a small machine that resembles a mangle. It is then carded by hipping with a pulun talanava or bow and then lightly rolled into tufts ready for spinning.

Spinning is done mainly by women, while weaving is done by both men and women. A tuft of cotton is held in the left hand and thread is spun from it on to a long weighted spindle or idda. The ends rest on a pod or coconut shell on the ground. This spindle is turned by the motion of the right hand against the thigh or by the fingers. The thread winds itself round the big end. A group of women gather around for the spinning process and it is done with a lot of joy and friendly spirit amidst songs sung by all of them.

The thread is then unwound on to a conical reel (hulu deva) made of split bamboo, after which it is wound on to a madava or a larger reel made of bamboo and string. Then it is wound onto a bobbin or harassala, ready to be laid onto the shuttles. The winding onto the bobbins is accomplished with the aid of a harassal ambarana yantraya, a winding machine consisting of a wheel with a string connecting it to a small rod that carries the bobbin; when the wheel is turned, the bobbin revolves rapidly and the reel is discharged onto it.

The thread that is required for the warp is wound off the bamboo and string reel directly to form a skein. This skein is laid on a temporary frame of sticks in a process known as dig-gahanava; this gives the required length of the warp. The weaver walks up and down along this framework disposing of the thread upon it with the help of a little forked stick or padu kule. When this process is completed the skeins are lifted off and rods are passed through the ends; this is laid horizontally a couple of feet above the ground and is kept on the stretch by strings attaching the rods to the posts at each end. Strung bows or het-li are passed through the warp to prevent tangling and to preserve the lease or angle on which it lies.

The warp is accurately sized on both sides with a starchy decoction in a process described as nal velanava, after which the threads are brushed, carefully separated, and arranged through the palal lanava process. The number of threads depends on the width of the cloth required. Ordinarily about 120 threads are taken as a span; when it is finally dry the warp is lifted up and readjusted on the loom itself. The cloth-beam of the loom has a groove into which the rod carrying the warp is laid which is held tightly when a turn is given to the beam. For the process of threading through the heddles and reed, the threads are broken one by one and rejoined after the process is completed. The length of the warp is usually made sufficient for two cloths in order to prevent this process from being repeated too often.

In Sri Lanka, the looms are known as aluva. The process of weaving is quite similar to that prevalent in India. It is set up in an open shed or al-ge on a platform or al-pila, attached to the outer verandah or porch or pila of the weaver's house; one of the rooms in the house is used as a storage room for materials, tools, and accessories.

For weaving plain cloth the shuttle or nadava is thrown to and fro while alternate threads of the warp or nul-heda are separated by the heddles or alu-vela (aluva); these are moved by pedals or pa-meduma made of coconut-shell (pol-katuva): these hang down into a space or al-vala beneath the loom in which the weaver's feet move up and down.

The heddles are attached to alu-kampaha, narrow pieces of wood that resemble the beam of a scale and are suspended by the middle to the beam above. In Sinhalese looms, two heddles are commonly used to separate the alternate warp threads. The weft is pressed home by a sleay or reed-frame, which is suspended from a beam above just like the heddles. The sleay (also rodu lella) has three parts: the poruvata or upper piece held by the weaver; the yattinan gal lella or lower piece below the web; and the alu-karala or teeth which are thin slips of cane through which warp threads are passed. Several pieces of equipment, like the pit-looms, shuttles, pirns, and heddles, are often made by the weavers.

When geometrical patterns are woven, the necessary warp threads are picked up with a narrow lathe or a weaver's sword (sema lella). A wider lathe is then inserted and turned up sideways to form a 'shed' for the passage of the shuttle. Before the sword is pulled out again, slips of cane are passed between the separated warp threads behind the heddles. Here they accumulate and preserve the pattern to aid in the weaving-process.

As the work progresses, it is wound by quarter turns on a square cloth-beam or on-kanda that is next to the weaver. The tension of the warp is regulated by a cod, which passes round a post (man-kanuva) at the remote end of it and then to the weaver's right hand near which it is fastened. This rope then passes through a bird-shaped block or 'kurulla' between the post and the web. This wooden bird bobs up and down as the work goes on. There is no thread-beam, but only a rod on which the warp threads are strung so that the warp is stretched out at full length while the work goes on. The web is kept tightly stretched at the near end by an arrangement of two crossed canes or katumal-heda of which the two ends next to the weaver are connected by a tight thread and the other two have pin-points which pass into the web and keep it stretched. Moveable thread-loops regulate the tension. The warp is supported at a point not far behind the heddles by a horizontal bar called alkanuve lella.

A freshly woven piece of loom-woven cloth is called alvala redda. The colours of the cloth vary, depending on the colour of the yarn, which is usually dyed red, blue, or black using traditional mineral and vegetable dyes.

MOTIFS AND DESIGNS

The designs used in traditional weaving were distinctive, and hence informative, sociologically and culturally. During the Kandyan period, the costumes and dresses of officials were critical in identifying them in service.

Along with geometrical patterns, a range of designs and motifs were woven into the cloth. Some of the common designs at Talagune included the mal petta, heen mal petta, maha mal petta, ata peti mala, para mala, deti mala, katuru mala, pehena mal petta, hali dangaya, hin negi dangaya, depota lanuwa, valalu lanuwa, diyarella, bo kola, iri kondu, pannan kura, hin ratava, maha ratava, gal-piyuma, domba mala, bota pata (two triangles, situated apex to apex), and the atapota lanuwa. Irregular patterns like birds, cobras, bo-leaves or large flowers were usually inserted by hand-work (ate veda) or in a tapestry format. The design pattern is, thus, often a combination of weaving and tapestry-work.

-

Bo leaf: The leaf of the Ficus Religiosa - held sacred by all the Buddhists - is prolifically used in all forms of Sinhalese arts and crafts as a motif. Variations of this motif are seen as tapestry designs in textiles.

- Katuru mala: Also known as katiri mala, this derives its name from crossing petals in a design that resembles a pair of scissors. The flower motif does not resemble any natural flower; it appears to be the creation of the craftsperson. This motif is found mainly in vaka deka (double curved form) and its variations.

- Lanuwa: This is a geometrical design, with two forms: the eka-pota lanuwa (one-ply plait design) and the depota lanuwa (chequered work or grass matting design), also known as thanthirikaya. The atatpota lanuwa has eight strands in its design and is found in Sinhalese weaving, though it is not very common.

- Para mala: This is an eight-petalled floral design, which is found frequently in the textiles woven at Talagune and is categorised as a geometrical design.

- Mal petta: This is a geometrical motif whose origin is not known. The variations of this motif are heen mal petta, maha mal petta, and thun pehena mal petta, which are widely found in textiles. This motif does not resemble any known flower in its appearance.

- Ata peti mala: This is a flower motif with eight petals; it does not resemble any naturally occurring flower. It is created as a geometrical design, widely found in woven Kandyan textiles.

- Lanugetaya: This is a plait motif, several variations of which are found in weaving. Common variations are the one ply plait and chequer work. Variations of this motif include the lanu dangaya, heen dangaya lanuwa, and valalu lanuwa.

- Bota pata: This is a geometrical motif in which two triangles are situated apex to apex.

- Gal piyuma: This is a geometrical motif, which consists of rectangles placed between two parallel lines, and is used chiefly in border designs.

- Diyarella: This is a design representation of a series of waves rising and falling in a gentle breeze. Several variations, with different degrees of elaboration, are found. Ananda Coomaraswamy calls it as the chevron or the zig-zag pattern and gives several examples of its angular forms. This design is very widely found in textile-weaving.

- Adara kondu: This is the name given to the motif where straight lines are found in the product; when this motif is found as part of textiles it is known as iri kondu.

- Bhayankaraya: This is a motif found in a lot of textiles; its origin and meaning are not known widely.

THE PRODUCT RANGE

1. TRADITIONAL

Sri Lankan clothing comprises several items that are not stitched garments but instead consist of whole pieces of cloth woven on the loom. This entails the need to make cloths of different shapes and sizes. The range of woven items includes cloth pieces that serve as garments for men (tuppoti) and women (pada, hela); aprons or bathing drawers for men (diya kacci), kerchiefs or shawls (lensu, ura mala), belts or pati; mats and quilts; sheets or etirili; carpets or paramadana, covers for chatties or floor spreads, pillow cases or kotta ura; and napkins or towels (indul kada). Other than these, common woven products include plain white, blue (kalu kangan), or red material that can be cut up for robes, jackets, caps, pillow-cases and betel leaf/nut bags. A variety of narrow braids are also made on the narrow looms, which are measured in width by the span or lakaya, and length by the carpenter's cubit or vadu riyana. Napkins were both plain and coarse, usually with embroidery on them, while handkerchieves were usually covered with pattern-work and were worn as turbans by men or they were used as a ceremonial covering for offerings.

- Somana: A particular kind of garment worn by men, somanas, are of several types, with different ones worn on different occasions. The social-status of the wearer was indicated by the type and design of the somana. The raja somana was worn by the king. Other kinds of somanas included the mudali somana and the vidane somana.

- Tuppotiya: A tuppotiya consists of a white cloth eight or nine cubits long, which comprises two pieces joined in the middle. Single widths were called padaya, and measured approximately six or seven cubits in length and four to six spans in width: these varied according to the caste of the owner. People from lower castes were allowed to wear only narrow cloths.

- Ohoriya: This was the skirt and bodice set, worn by women belonging to the higher castes. Women of lower castes wore two short cloths, one of which was wrapped around the loins, while the other was thrown over the shoulder.

- Etirilla: The etirilla is the equivalent of the Indian dhurrie, only much thinner. It is almost entirely made up of cloth covered with pattern work, with only a few pieces that have plain centres and worked borders. The usual size is about 6 feet x 3.5 feet or less, though some pieces can be as large as 11 feet x 5 feet.

- Diya kacci: This was the name given to undergarments made in one piece with a large apron in the front, a narrower flap with less ornamentation behind it, and a woven tape to tie around the waist. These also served as bathing and running costumes and are said to have originated from Kandy. Some of these garments were plain while others were very elaborately ornamented. These garments were made from special looms with double heddles or alu-vel. The looms were known as ata-vel_aluva. Special small looms were also used to make braids. The belt or pattiya of a diya kacci was sometimes made in one piece with the rest. Diya kacci were about five to six feet in length and the apron, on average, was about 1.5 X 2 feet.

- Gahoni: This was the name given to bell-shaped or skirt-shaped pieces of cloth used to cover baskets or pots of food or other offerings carried on a yoke for the king or for a temple. The appearance was that of a three-flounced skirt with each flounce having a pattern border. The 'skirt' was made up of a single, straight piece of cloth joined up with one seam and left open at both ends. One end was turned over and gathered in upon a string, thus forming the waist and two of the flounces; the third flounce was a separate piece of cloth sewn on between the two others. Belts worn over the dress were often Indian in origin.

- Ura Malaya: These are shawls, draped around the shoulder like in India.

- Welitara bedspreads: These were made of coarse yarn from Welitara and were attractively done up with traditional designs of iddamala and depota lanuva, indicative of the regional identity/ies.

Handloom weaving of Purulia, West Bengal,

Jamdani was originally a dress material for women and men but nowadays it is mainly in the form of saris with a great variety of designs with geometrical motifs made on simple frame-or pit-looms. The saris are woven with a silk warp and a cotton weft. The extra weft inlaid pattern is worked with a single cotton thread and after weaving the motif the thread is not cut but carried on to the next motif. A paper pattern is kept beneath during the weaving process and when the weft thread approaches the area where a flower or other figure has to be inserted a set of bamboo needles is taken and different coloured yarns are wound around each design. As every weft or woof thread passes through the warp, the weaver sews down the intersected portion of the pattern with any of the needles and the pattern is completed. When the pattern is continuous as in a border, the master weaver does not use a paper pattern. Two weavers weave the jamdani sari. Traditionally jamdanis are in white with designs in bleached white. However, lightly dyed backgrounds with designs in white, maroon, black, green, gold, and silver are now; muga silk of a golden colour is also seen. There is a key difference in the weaving technique of extra weft designing between jamdanis and tangails; the embroidery thread in jamdani is inserted after every ground pick whereas in tangails the embroidery thread is inserted after two ground picks. The weaving of tangails is no longer done in a traditional manner. The main characteristic of tangails is the extra weft butis, tiny motifs repeated all over the ground. The main cotton weaving centers are Shantipur, Dhaniakhal, Begampur, and Farasdanga. These centers are involved in the weaving of fine-textured saris and dhotis for men. Atpur in Hooghly district is well-known for coarser saris and dhotis, used for everyday wear. At Shantipur, fine textured saris and a uniform weave of 100-112 counts in the warp and the weft are done. The upper and lower borders are decorated with extra warp designs of twisted yarn; if in addition an extra weft yarn of one or two colours are used then the solid effect created is called as mina-kaj or enamel work. When the decorations look the same on both sides of the cloth they are called do-rookha or double sided designs. The saris of Shantipur have dyed cotton-silk, art-silk, viscose yarns, and gold and silver zaris for the borders. The background of the saris has fine and delicate checks, stripes, or a texture created by coloured threads or the combined used of fine and thicker counts of yarn. The anchala or pallava or pallu of the sari hangs from the shoulder and has butis or jamdani designs in an extra weft beautifully arranged along with stripes of many different types and widths. Some tie and dye designs are also being used for the anchalas of Shantipur saris. Traditional Shantipur sari borders or paars have names like bhomra or bumble bee, tabij or amulet, rajmahal or royal palace, ardha chandra or half moon, chandmala or garland of moons, ansh or fish scale, hathi or elephant, ratan chokh or gem eyed, benki or spiral, tara or star, and phool or flower. The well known Nilamabari sari is of a deep navy-blue colour like the sky on a new moon night; the borders have silver zari-like the stars and the pallu is decorated with stripes of different thickness, called sajanshoi, in colours complementary to the border. There is a rich tradition in Bengal of weaving richly patterned cotton saris with heavy borders which contrasts with a finely textured body. Dhaniakhali in Hooghly district was once famous for superfine dhotis but due to failing demand, has switched over to saris in pastel shades. Farasdanga in the same district continues to make fine dhotis, perhaps the finest in Bengal. Begampur also in Hooghly district specialises in loosely woven, light-weight and translucent saris. In contrast to the Dhaniakhali saris, the saris of Begumpur have deep and bright colours. In the districts of West Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, Maldah, and Cooch Behar in north Bengal, there is a rich tradition of weaving handloom cotton textiles among the tribal and semi-tribal people. Rajbanshis weave saris with very attractive designs of checks and stripes on simple pit-looms. The sarongs of the Polia women are made by joining together two very compact strips woven on simple primitive looms made of short pieces of bamboo stick and a narrow strip of wood about 3 cm wide and 60 cm long. The tribals of West Dinajpur make beautifully patterned, multicoloured, narrow jute carpets on similar looms. These dhokras are joined together and used as sleeping mats or blankets. Silk weaving in Bengal has existed from the ancient times as mentioned in the Arthashastra, a treatise on economics by Kautilya; kausheya vastra or wild silk or tussar weaving is still carried out by the weavers of Bankura, Purulia, and Birbhum districts. The cultivation of mulberry silk and its weaving is carried out in the plains of West Bengal. The district of Maldah on the north bank of the Ganga is today the most important centre for silk rearing in West Bengal. The other districts where silk yarn is made are Murshidabad, Birbhum, Bankura, and Purulia districts. Baluchar silks were originally used by nawabs and Muslim aristocrats of the Murshidabad district as tapestry material; however Hindu noblemen used the raw silk Baluchar as saris in which the ground scheme of decoration is a very wide pallu with a panel of mango or paisley motifs at the centre surrounded by smaller rectangles depicting different scenes. The sari borders were narrow with floral and foliage motifs and the ground of the sari was covered with small paisley and other floral designs in restrained but bright colour schemes. Another familiar motif for the body of the sari was diagonal butis; today similar saris are being woven at Murshidabad and Varanasi which have smaller anchalas according to contemporary tastes. The traditional jala technique is used for this. The interesting feature of Baluchar saris was the combination of stylised animal and bird motifs incorporated in floral and paisley decorations. The other motifs used are hunters on horses, elephants, and scenes from nawab's court; there were also depictions of the sahibs and the memsahibs of the British era. The advent of railways and steamboats were also depicted as motifs on the Baluchar saris. The silk yarn used for Baluchar saris was not twisted and so had a soft and heavy texture. The ground colours were limited but permanent in nature and are fresh after so many years. Before modern chemical dyes became common, indigenous vegetable dyes were used to dye both silk and cotton yarn. Murshidabad is also known for its cowdial saris made of fine mulberry silk with flat, deep- red or maroon borders made with three shuttles. The borders are topped with fine serrated design in gold zari and a few fine lines in gold on the ground of the sari close to the borders. The fine gold lines are supposed to represent the fine trail left on its path by a live cowrie mollusc, thus giving the name, cowdial. Murshidabad silks are popular for hand-printed designs and other materials which are also printed with wooden blocks. The main textile hand-printing centres in West Bengal are in Calcutta and Srirampur in the Hooghly district. Vishnupur in Bankura district also has a tradition of silk sari weaving. The old Vishnupur saris have a lot of similarity with the kataki designs of Odisha. In the districts of Bankura, Birbhum, Purulia, Murshidabad, and Maldah the weavers make plain silk fabrics in rich and varied textures. Tussar and mulberry silk are used by the weavers. Traditional jamdani saris with geometrical designs and cotton tangails are very popular and continue to be woven by weavers originally from Bangladesh. Being light they are excellent for everyday wear in a tropical country like India and come in pastel colours. There are weavers producing medium quality saris in Birbhum district. Another sari is the Shantipuri, mostly produced on pit-looms. Also see: Batik on Textiles Embroidery of W Bengal Hill Crafts of Darjeeling Kantha Embroidery of W Bengal Zari, Zardozi, Tinsel Embroidery

Jamdani was originally a dress material for women and men but nowadays it is mainly in the form of saris with a great variety of designs with geometrical motifs made on simple frame-or pit-looms. The saris are woven with a silk warp and a cotton weft. The extra weft inlaid pattern is worked with a single cotton thread and after weaving the motif the thread is not cut but carried on to the next motif. A paper pattern is kept beneath during the weaving process and when the weft thread approaches the area where a flower or other figure has to be inserted a set of bamboo needles is taken and different coloured yarns are wound around each design. As every weft or woof thread passes through the warp, the weaver sews down the intersected portion of the pattern with any of the needles and the pattern is completed. When the pattern is continuous as in a border, the master weaver does not use a paper pattern. Two weavers weave the jamdani sari. Traditionally jamdanis are in white with designs in bleached white. However, lightly dyed backgrounds with designs in white, maroon, black, green, gold, and silver are now; muga silk of a golden colour is also seen. There is a key difference in the weaving technique of extra weft designing between jamdanis and tangails; the embroidery thread in jamdani is inserted after every ground pick whereas in tangails the embroidery thread is inserted after two ground picks. The weaving of tangails is no longer done in a traditional manner. The main characteristic of tangails is the extra weft butis, tiny motifs repeated all over the ground. The main cotton weaving centers are Shantipur, Dhaniakhal, Begampur, and Farasdanga. These centers are involved in the weaving of fine-textured saris and dhotis for men. Atpur in Hooghly district is well-known for coarser saris and dhotis, used for everyday wear. At Shantipur, fine textured saris and a uniform weave of 100-112 counts in the warp and the weft are done. The upper and lower borders are decorated with extra warp designs of twisted yarn; if in addition an extra weft yarn of one or two colours are used then the solid effect created is called as mina-kaj or enamel work. When the decorations look the same on both sides of the cloth they are called do-rookha or double sided designs. The saris of Shantipur have dyed cotton-silk, art-silk, viscose yarns, and gold and silver zaris for the borders. The background of the saris has fine and delicate checks, stripes, or a texture created by coloured threads or the combined used of fine and thicker counts of yarn. The anchala or pallava or pallu of the sari hangs from the shoulder and has butis or jamdani designs in an extra weft beautifully arranged along with stripes of many different types and widths. Some tie and dye designs are also being used for the anchalas of Shantipur saris. Traditional Shantipur sari borders or paars have names like bhomra or bumble bee, tabij or amulet, rajmahal or royal palace, ardha chandra or half moon, chandmala or garland of moons, ansh or fish scale, hathi or elephant, ratan chokh or gem eyed, benki or spiral, tara or star, and phool or flower. The well known Nilamabari sari is of a deep navy-blue colour like the sky on a new moon night; the borders have silver zari-like the stars and the pallu is decorated with stripes of different thickness, called sajanshoi, in colours complementary to the border. There is a rich tradition in Bengal of weaving richly patterned cotton saris with heavy borders which contrasts with a finely textured body. Dhaniakhali in Hooghly district was once famous for superfine dhotis but due to failing demand, has switched over to saris in pastel shades. Farasdanga in the same district continues to make fine dhotis, perhaps the finest in Bengal. Begampur also in Hooghly district specialises in loosely woven, light-weight and translucent saris. In contrast to the Dhaniakhali saris, the saris of Begumpur have deep and bright colours. In the districts of West Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, Maldah, and Cooch Behar in north Bengal, there is a rich tradition of weaving handloom cotton textiles among the tribal and semi-tribal people. Rajbanshis weave saris with very attractive designs of checks and stripes on simple pit-looms. The sarongs of the Polia women are made by joining together two very compact strips woven on simple primitive looms made of short pieces of bamboo stick and a narrow strip of wood about 3 cm wide and 60 cm long. The tribals of West Dinajpur make beautifully patterned, multicoloured, narrow jute carpets on similar looms. These dhokras are joined together and used as sleeping mats or blankets. Silk weaving in Bengal has existed from the ancient times as mentioned in the Arthashastra, a treatise on economics by Kautilya; kausheya vastra or wild silk or tussar weaving is still carried out by the weavers of Bankura, Purulia, and Birbhum districts. The cultivation of mulberry silk and its weaving is carried out in the plains of West Bengal. The district of Maldah on the north bank of the Ganga is today the most important centre for silk rearing in West Bengal. The other districts where silk yarn is made are Murshidabad, Birbhum, Bankura, and Purulia districts. Baluchar silks were originally used by nawabs and Muslim aristocrats of the Murshidabad district as tapestry material; however Hindu noblemen used the raw silk Baluchar as saris in which the ground scheme of decoration is a very wide pallu with a panel of mango or paisley motifs at the centre surrounded by smaller rectangles depicting different scenes. The sari borders were narrow with floral and foliage motifs and the ground of the sari was covered with small paisley and other floral designs in restrained but bright colour schemes. Another familiar motif for the body of the sari was diagonal butis; today similar saris are being woven at Murshidabad and Varanasi which have smaller anchalas according to contemporary tastes. The traditional jala technique is used for this. The interesting feature of Baluchar saris was the combination of stylised animal and bird motifs incorporated in floral and paisley decorations. The other motifs used are hunters on horses, elephants, and scenes from nawab's court; there were also depictions of the sahibs and the memsahibs of the British era. The advent of railways and steamboats were also depicted as motifs on the Baluchar saris. The silk yarn used for Baluchar saris was not twisted and so had a soft and heavy texture. The ground colours were limited but permanent in nature and are fresh after so many years. Before modern chemical dyes became common, indigenous vegetable dyes were used to dye both silk and cotton yarn. Murshidabad is also known for its cowdial saris made of fine mulberry silk with flat, deep- red or maroon borders made with three shuttles. The borders are topped with fine serrated design in gold zari and a few fine lines in gold on the ground of the sari close to the borders. The fine gold lines are supposed to represent the fine trail left on its path by a live cowrie mollusc, thus giving the name, cowdial. Murshidabad silks are popular for hand-printed designs and other materials which are also printed with wooden blocks. The main textile hand-printing centres in West Bengal are in Calcutta and Srirampur in the Hooghly district. Vishnupur in Bankura district also has a tradition of silk sari weaving. The old Vishnupur saris have a lot of similarity with the kataki designs of Odisha. In the districts of Bankura, Birbhum, Purulia, Murshidabad, and Maldah the weavers make plain silk fabrics in rich and varied textures. Tussar and mulberry silk are used by the weavers. Traditional jamdani saris with geometrical designs and cotton tangails are very popular and continue to be woven by weavers originally from Bangladesh. Being light they are excellent for everyday wear in a tropical country like India and come in pastel colours. There are weavers producing medium quality saris in Birbhum district. Another sari is the Shantipuri, mostly produced on pit-looms. Also see: Batik on Textiles Embroidery of W Bengal Hill Crafts of Darjeeling Kantha Embroidery of W Bengal Zari, Zardozi, Tinsel Embroidery

Handloom Weaving of West Bengal,

Jamdani was originally a dress material for women and men but nowadays it is mainly in the form of saris with a great variety of designs with geometrical motifs made on simple frame-or pit-looms. The saris are woven with a silk warp and a cotton weft. The extra weft inlaid pattern is worked with a single cotton thread and after weaving the motif the thread is not cut but carried on to the next motif. A paper pattern is kept beneath during the weaving process and when the weft thread approaches the area where a flower or other figure has to be inserted a set of bamboo needles is taken and different coloured yarns are wound around each design. As every weft or woof thread passes through the warp, the weaver sews down the intersected portion of the pattern with any of the needles and the pattern is completed. When the pattern is continuous as in a border, the master weaver does not use a paper pattern. Two weavers weave the jamdani sari. Traditionally jamdanis are in white with designs in bleached white. However, lightly dyed backgrounds with designs in white, maroon, black, green, gold, and silver are now; muga silk of a golden colour is also seen. There is a key difference in the weaving technique of extra weft designing between jamdanis and tangails; the embroidery thread in jamdani is inserted after every ground pick whereas in tangails the embroidery thread is inserted after two ground picks. The weaving of tangails is no longer done in a traditional manner. The main characteristic of tangails is the extra weft butis, tiny motifs repeated all over the ground. The main cotton weaving centers are Shantipur, Dhaniakhal, Begampur, and Farasdanga. These centers are involved in the weaving of fine-textured saris and dhotis for men. Atpur in Hooghly district is well-known for coarser saris and dhotis, used for everyday wear. At Shantipur, fine textured saris and a uniform weave of 100-112 counts in the warp and the weft are done. The upper and lower borders are decorated with extra warp designs of twisted yarn; if in addition an extra weft yarn of one or two colours are used then the solid effect created is called as mina-kaj or enamel work. When the decorations look the same on both sides of the cloth they are called do-rookha or double sided designs. The saris of Shantipur have dyed cotton-silk, art-silk, viscose yarns, and gold and silver zaris for the borders. The background of the saris has fine and delicate checks, stripes, or a texture created by coloured threads or the combined used of fine and thicker counts of yarn. The anchala or pallava or pallu of the sari hangs from the shoulder and has butis or jamdani designs in an extra weft beautifully arranged along with stripes of many different types and widths. Some tie and dye designs are also being used for the anchalas of Shantipur saris. Traditional Shantipur sari borders or paars have names like bhomra or bumble bee, tabij or amulet, rajmahal or royal palace, ardha chandra or half moon, chandmala or garland of moons, ansh or fish scale, hathi or elephant, ratan chokh or gem eyed, benki or spiral, tara or star, and phool or flower. The well known Nilamabari sari is of a deep navy-blue colour like the sky on a new moon night; the borders have silver zari-like the stars and the pallu is decorated with stripes of different thickness, called sajanshoi, in colours complementary to the border. There is a rich tradition in Bengal of weaving richly patterned cotton saris with heavy borders which contrasts with a finely textured body. Dhaniakhali in Hooghly district was once famous for superfine dhotis but due to failing demand, has switched over to saris in pastel shades. Farasdanga in the same district continues to make fine dhotis, perhaps the finest in Bengal. Begampur also in Hooghly district specialises in loosely woven, light-weight and translucent saris. In contrast to the Dhaniakhali saris, the saris of Begumpur have deep and bright colours. In the districts of West Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, Maldah, and Cooch Behar in north Bengal, there is a rich tradition of weaving handloom cotton textiles among the tribal and semi-tribal people. Rajbanshis weave saris with very attractive designs of checks and stripes on simple pit-looms. The sarongs of the Polia women are made by joining together two very compact strips woven on simple primitive looms made of short pieces of bamboo stick and a narrow strip of wood about 3 cm wide and 60 cm long. The tribals of West Dinajpur make beautifully patterned, multicoloured, narrow jute carpets on similar looms. These dhokras are joined together and used as sleeping mats or blankets. Silk weaving in Bengal has existed from the ancient times as mentioned in the Arthashastra, a treatise on economics by Kautilya; kausheya vastra or wild silk or tussar weaving is still carried out by the weavers of Bankura, Purulia, and Birbhum districts. The cultivation of mulberry silk and its weaving is carried out in the plains of West Bengal. The district of Maldah on the north bank of the Ganga is today the most important centre for silk rearing in West Bengal. The other districts where silk yarn is made are Murshidabad, Birbhum, Bankura, and Purulia districts. Baluchar silks were originally used by nawabs and Muslim aristocrats of the Murshidabad district as tapestry material; however Hindu noblemen used the raw silk Baluchar as saris in which the ground scheme of decoration is a very wide pallu with a panel of mango or paisley motifs at the centre surrounded by smaller rectangles depicting different scenes. The sari borders were narrow with floral and foliage motifs and the ground of the sari was covered with small paisley and other floral designs in restrained but bright colour schemes. Another familiar motif for the body of the sari was diagonal butis; today similar saris are being woven at Murshidabad and Varanasi which have smaller anchalas according to contemporary tastes. The traditional jala technique is used for this. The interesting feature of Baluchar saris was the combination of stylised animal and bird motifs incorporated in floral and paisley decorations. The other motifs used are hunters on horses, elephants, and scenes from nawab's court; there were also depictions of the sahibs and the memsahibs of the British era. The advent of railways and steamboats were also depicted as motifs on the Baluchar saris. The silk yarn used for Baluchar saris was not twisted and so had a soft and heavy texture. The ground colours were limited but permanent in nature and are fresh after so many years. Before modern chemical dyes became common, indigenous vegetable dyes were used to dye both silk and cotton yarn. Murshidabad is also known for its cowdial saris made of fine mulberry silk with flat, deep- red or maroon borders made with three shuttles. The borders are topped with fine serrated design in gold zari and a few fine lines in gold on the ground of the sari close to the borders. The fine gold lines are supposed to represent the fine trail left on its path by a live cowrie mollusc, thus giving the name, cowdial. Murshidabad silks are popular for hand-printed designs and other materials which are also printed with wooden blocks. The main textile hand-printing centres in West Bengal are in Calcutta and Srirampur in the Hooghly district. Vishnupur in Bankura district also has a tradition of silk sari weaving. The old Vishnupur saris have a lot of similarity with the kataki designs of Odisha. In the districts of Bankura, Birbhum, Purulia, Murshidabad, and Maldah the weavers make plain silk fabrics in rich and varied textures. Tussar and mulberry silk are used by the weavers. Traditional jamdani saris with geometrical designs and cotton tangails are very popular and continue to be woven by weavers originally from Bangladesh. Being light they are excellent for everyday wear in a tropical country like India and come in pastel colours. There are weavers producing medium quality saris in Birbhum district. Another sari is the Shantipuri, mostly produced on pit-looms.

Jamdani was originally a dress material for women and men but nowadays it is mainly in the form of saris with a great variety of designs with geometrical motifs made on simple frame-or pit-looms. The saris are woven with a silk warp and a cotton weft. The extra weft inlaid pattern is worked with a single cotton thread and after weaving the motif the thread is not cut but carried on to the next motif. A paper pattern is kept beneath during the weaving process and when the weft thread approaches the area where a flower or other figure has to be inserted a set of bamboo needles is taken and different coloured yarns are wound around each design. As every weft or woof thread passes through the warp, the weaver sews down the intersected portion of the pattern with any of the needles and the pattern is completed. When the pattern is continuous as in a border, the master weaver does not use a paper pattern. Two weavers weave the jamdani sari. Traditionally jamdanis are in white with designs in bleached white. However, lightly dyed backgrounds with designs in white, maroon, black, green, gold, and silver are now; muga silk of a golden colour is also seen. There is a key difference in the weaving technique of extra weft designing between jamdanis and tangails; the embroidery thread in jamdani is inserted after every ground pick whereas in tangails the embroidery thread is inserted after two ground picks. The weaving of tangails is no longer done in a traditional manner. The main characteristic of tangails is the extra weft butis, tiny motifs repeated all over the ground. The main cotton weaving centers are Shantipur, Dhaniakhal, Begampur, and Farasdanga. These centers are involved in the weaving of fine-textured saris and dhotis for men. Atpur in Hooghly district is well-known for coarser saris and dhotis, used for everyday wear. At Shantipur, fine textured saris and a uniform weave of 100-112 counts in the warp and the weft are done. The upper and lower borders are decorated with extra warp designs of twisted yarn; if in addition an extra weft yarn of one or two colours are used then the solid effect created is called as mina-kaj or enamel work. When the decorations look the same on both sides of the cloth they are called do-rookha or double sided designs. The saris of Shantipur have dyed cotton-silk, art-silk, viscose yarns, and gold and silver zaris for the borders. The background of the saris has fine and delicate checks, stripes, or a texture created by coloured threads or the combined used of fine and thicker counts of yarn. The anchala or pallava or pallu of the sari hangs from the shoulder and has butis or jamdani designs in an extra weft beautifully arranged along with stripes of many different types and widths. Some tie and dye designs are also being used for the anchalas of Shantipur saris. Traditional Shantipur sari borders or paars have names like bhomra or bumble bee, tabij or amulet, rajmahal or royal palace, ardha chandra or half moon, chandmala or garland of moons, ansh or fish scale, hathi or elephant, ratan chokh or gem eyed, benki or spiral, tara or star, and phool or flower. The well known Nilamabari sari is of a deep navy-blue colour like the sky on a new moon night; the borders have silver zari-like the stars and the pallu is decorated with stripes of different thickness, called sajanshoi, in colours complementary to the border. There is a rich tradition in Bengal of weaving richly patterned cotton saris with heavy borders which contrasts with a finely textured body. Dhaniakhali in Hooghly district was once famous for superfine dhotis but due to failing demand, has switched over to saris in pastel shades. Farasdanga in the same district continues to make fine dhotis, perhaps the finest in Bengal. Begampur also in Hooghly district specialises in loosely woven, light-weight and translucent saris. In contrast to the Dhaniakhali saris, the saris of Begumpur have deep and bright colours. In the districts of West Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri, Maldah, and Cooch Behar in north Bengal, there is a rich tradition of weaving handloom cotton textiles among the tribal and semi-tribal people. Rajbanshis weave saris with very attractive designs of checks and stripes on simple pit-looms. The sarongs of the Polia women are made by joining together two very compact strips woven on simple primitive looms made of short pieces of bamboo stick and a narrow strip of wood about 3 cm wide and 60 cm long. The tribals of West Dinajpur make beautifully patterned, multicoloured, narrow jute carpets on similar looms. These dhokras are joined together and used as sleeping mats or blankets. Silk weaving in Bengal has existed from the ancient times as mentioned in the Arthashastra, a treatise on economics by Kautilya; kausheya vastra or wild silk or tussar weaving is still carried out by the weavers of Bankura, Purulia, and Birbhum districts. The cultivation of mulberry silk and its weaving is carried out in the plains of West Bengal. The district of Maldah on the north bank of the Ganga is today the most important centre for silk rearing in West Bengal. The other districts where silk yarn is made are Murshidabad, Birbhum, Bankura, and Purulia districts. Baluchar silks were originally used by nawabs and Muslim aristocrats of the Murshidabad district as tapestry material; however Hindu noblemen used the raw silk Baluchar as saris in which the ground scheme of decoration is a very wide pallu with a panel of mango or paisley motifs at the centre surrounded by smaller rectangles depicting different scenes. The sari borders were narrow with floral and foliage motifs and the ground of the sari was covered with small paisley and other floral designs in restrained but bright colour schemes. Another familiar motif for the body of the sari was diagonal butis; today similar saris are being woven at Murshidabad and Varanasi which have smaller anchalas according to contemporary tastes. The traditional jala technique is used for this. The interesting feature of Baluchar saris was the combination of stylised animal and bird motifs incorporated in floral and paisley decorations. The other motifs used are hunters on horses, elephants, and scenes from nawab's court; there were also depictions of the sahibs and the memsahibs of the British era. The advent of railways and steamboats were also depicted as motifs on the Baluchar saris. The silk yarn used for Baluchar saris was not twisted and so had a soft and heavy texture. The ground colours were limited but permanent in nature and are fresh after so many years. Before modern chemical dyes became common, indigenous vegetable dyes were used to dye both silk and cotton yarn. Murshidabad is also known for its cowdial saris made of fine mulberry silk with flat, deep- red or maroon borders made with three shuttles. The borders are topped with fine serrated design in gold zari and a few fine lines in gold on the ground of the sari close to the borders. The fine gold lines are supposed to represent the fine trail left on its path by a live cowrie mollusc, thus giving the name, cowdial. Murshidabad silks are popular for hand-printed designs and other materials which are also printed with wooden blocks. The main textile hand-printing centres in West Bengal are in Calcutta and Srirampur in the Hooghly district. Vishnupur in Bankura district also has a tradition of silk sari weaving. The old Vishnupur saris have a lot of similarity with the kataki designs of Odisha. In the districts of Bankura, Birbhum, Purulia, Murshidabad, and Maldah the weavers make plain silk fabrics in rich and varied textures. Tussar and mulberry silk are used by the weavers. Traditional jamdani saris with geometrical designs and cotton tangails are very popular and continue to be woven by weavers originally from Bangladesh. Being light they are excellent for everyday wear in a tropical country like India and come in pastel colours. There are weavers producing medium quality saris in Birbhum district. Another sari is the Shantipuri, mostly produced on pit-looms.

Handmade Lokta/Daphne Paper of Nepal,

The dense peaked landscapes of the mountainous region of Nepal are the habitat of the high attitude plant Daphne (lokta) which has been used for centuries for making paper. It is conjectured that the Chinese technique of paper-making was brought from Tibet over the ancient trade routes about a thousand years ago and that skilled Nepalese artisans have been producing paper and supplying the Tibetan Buddhist monasteries ever since. The Nepalese themselves have found myriad uses for this paper in their daily life - these include, among others, its use in writing manuscripts, printing sacred texts, inscribing valuable documents, making ritual masks, constructing kites, rolling incense, packaging, and wrapping precious stones (as its soft fibres do not scratch the surface). In many local communities all over Nepal, artisans have been making paper by hand for over a thousand years, using age-old labour intensive techniques. The paper-making industry is of crucial importance to the economy, since many families in the Himalayan foothills supplement their farming income with that from making paper.