In Manipur, two types of wood, locally known as 'want' and 'heijuga', are used for wood-carving. Trees are cut when they reach full maturity and the logs are seasoned for a period of three to four months, in order to preserve the original colour of the wood. 'Wang' wood is lightweight and does not crack easily, whereas 'heijuga' wood needs to be seasoned properly before use or else it warps. The heijuga is weighty. The ancient traditional motifs of Manipuri culture are carved by the artisans. Lacquer work similar to that of Myanmar can also be found in Manipur. The resin is applied in a thickened or liquid state for ornamentation of swords, scabbards, sword handles, and leather belts.

A limited amount of wood carving is done in the Garo hills. They manufacture toys, mainly human figures, animals, and birds.

Dimapur and Kohima are the two important wood carving centres of Nagaland. The carved wooden objects of Nagaland are ritualistic and functional in purpose. Strictly a male craft, it is ceremonial and ritualistic art related to the fertility cult. The carving of human figures, elephants, pythons, hornbills etc are etched high into the pillars of morung or bachelor's dormitory. House posts, gates, drums, husking troughs, grave effigies are all carved elaborately. Simple wooden utensils like food dishes, spoons and mugs are crafted for daily usage. The speciality here is no joints in the objects manufactured. All the objects are made out of single piece of wood.

Wood carving is widely practiced in Tamil Nadu. The famed temple chariots are made of wood and are full of intricate carvings. The Padmanabhapuram palace in Kanyakumari district is an exquisite wooden palace, a striking example of the detailing in wood-carving in Tamil Nadu. Built in the 19th and 20th centuries, this has intricately carved roof gables, lathe-turned columns, carved window grills, decorated wooden ceilings. The ancestral homes are found in the districts of Ramnad, Pudukottai and Thiruchirapalli. Even today house entrance doors made of wood have detailing done on them as the front door is considered a sacred threshold. The carvings on the door panels are of Hindu deities and auspicious motifs like the hamsa/mythical swan, padma/lotus, poornakumbha /cornucopia, kaamadhenu and patterned floral motifs. Other carved wooden items made are small shrines and deities, low carved stools for marriages, carved fans for the deity, fertility couples and various small ceremonial containers. The carved panels of deities fixed to either end of a metre-long pole were the other ceremonial items. These panels are called kavadi and afre carried on the shoulders of a person to fulfill the vow to Lord Murugan or Karthikeya. Intricately carved wooden kitchen instruments such as grinders, vegetable cutters, serving ladle holders are items given in dowry. The range of skills is also exhibited in carved wooden smaller objects like wooden covers for manuscripts, spices and kumkum boxes and games and toys. Toys made of wood are lathe-turned and lacquered, especially the cooking vessels and walkers known as kadasal. These are brightly coloured, inexpensive and are popular all over the state. Carved wooden toys dolls and elephants which exhibit the range of skills of the artisan are also made.

The wood work of Rajasthan is of a very high quality. It is seen in the profusely carved doors and projecting niches and balconies of houses. Carved furniture, mainly beds and divans, are found in Barmer. Jali as well as other wood-carving is found in Bikaner. Bassi, near Chittogarh, has a reputation for high-quality wood-carving and painting and the products made here are mainly for ritual use. The other product made is the kavadh which is wooden shrine opening out into seven panels with painted scenes; the sindoor box in the shape of a peacock given to the girl as part of her wedding trousseau is also important. Pipar and Bhari Sajanpur in Pali district make finely sectioned, turned bowls which are exquisitely proportioned and meant for the use of Jain monks. These bowls are paper thin and are made form rohida wood.

Wood craft, an ancient art form was originally patronised by the Buddhist monasteries, where ornate wood plaques, Buddhist symbols and icons continue to adorn the walls. Wooden images of Lord Buddha, and wooden containers and utensils are extensively used in Sikkim. The local Sikkimese use a wooden pot for churning curd to make butter, where the churner is also made of wood.

Intricately carved, painted and polished Choktse or small foldable wooden tables aptly define the intricacies involved in this art form. Other exquisite carved products include Bakchok – square table, lucky signs, decorative plaques amongst others where the design style predominantly includes traditional Buddhist figures - dragons, birds and phoenix. Wooden masks, also an ancient craft is particularly famous in Sikkim for its depiction of diverse emotions from serene, calm, spiritual to aggression and intensity.

Wood is the main raw material and locally sourced forest wood of 3 types – namely tooni (toona celiata), rani chaap (macalia exelsa) and okner (walnut) are said to be in use in Gangtok, Sikkim for wood carving.

The design process starts with sketching on paper which acts as a stencil for the design to be transferred onto smoothed and cut wood. The design is traced as the charcoal seeps in through the holes created on the outlines. Once the wood is ready, several types of tools – knives, curved and straight chisels – locally known as Tikkyu and Ika respectively, hammer, saw, drilling machine etc., with varied thickness and nibs – from flat, angular to curved, are used to achieve the required intricacies in the final product. The craftsmen use straight and curved chisels to work free hand without using any references. Finishing includes smoothing, coating with a layer of primer before painting in varied colours - orange, golden, red, blue, pink, green, brown and ending with a coat of protected varnish.

Wood carving is widely practiced in Tamil Nadu. The famed temple chariots are made of wood and are full of intricate carvings. The Padmanabhapuram palace in Kanyakumari district is an exquisite wooden palace, a striking example of the detailing in wood-carving in Tamil Nadu. Built in the 19th and 20th centuries, this has intricately carved roof gables, lathe-turned columns, carved window grills, decorated wooden ceilings. The ancestral homes are found in the districts of Ramnad, Pudukottai and Thiruchirapalli. Even today house entrance doors made of wood have detailing done on them as the front door is considered a sacred threshold. The carvings on the door panels are of Hindu deities and auspicious motifs like the hamsa/mythical swan, padma/lotus, poornakumbha /cornucopia, kaamadhenu and patterned floral motifs. Other carved wooden items made are small shrines and deities, low carved stools for marriages, carved fans for the deity, fertility couples and various small ceremonial containers. The carved panels of deities fixed to either end of a metre-long pole were the other ceremonial items. These panels are called kavadi and afre carried on the shoulders of a person to fulfill the vow to Lord Murugan or Karthikeya. Intricately carved wooden kitchen instruments such as grinders, vegetable cutters, serving ladle holders are items given in dowry. The range of skills is also exhibited in carved wooden smaller objects like wooden covers for manuscripts, spices and kumkum boxes and games and toys. Toys made of wood are lathe-turned and lacquered, especially the cooking vessels and walkers known as kadasal. These are brightly coloured, inexpensive and are popular all over the state. Carved wooden toys dolls and elephants which exhibit the range of skills of the artisan are also made.

The diverse traditions and religions in Tripura are visible in the wood craft. Wood-carving is widely practised among the hill tribes as well as among those settled in the plains, although the nature of the carving differs. Rhinoceros models and tribal figures can be seen together with wooden plaques of Hindu deities like Durga and Kali.

Uttar Pradesh is well-known for its wood work and there is a large variety of wood used here including sisam, sal and dudhi. The wood work done at Saharanpur has the typical perforated lacy work. For the big pieces small lattice frames are made and fitted together. The wood used here is a rich medium-brown shisham with deep grains. The wood carvers at Saharanpur have a natural skill for fine handwork and the fret work --- jali, mehrab or archways motifs --and grapevine or the anguri work are similar to the stone design work of Agra. Brass, copper, ivory and plastic inlay work is also done here. Inlay work in Nagina is done on ebony wood. Popularly known as the “sheesham wood village”, Saharanpur is home to some of India's finest woodcarvers. The city is internationally famous for this craft and its artisans who have been creating magic for years. They “breathe life into dead trees” is how they like to put it. Intricate and fine workmanship are what makes these products unique. The vine-leaf patterns are a speciality of this region. Geometric and figurative carving is also done along with superb brass inlay work. Other materials like wrought iron, ceramics and glass are being combined with wood to give a new dimension to the craft and “contemporize” the traditional products. A wide range of wood types is used to make products: sheesham for small items, teakwood for furniture and mango for antique objects. All of them go through the same basic steps: slicing, carving, inlaying, sanding, polishing and assembling. Craftsmen specialize in one (or more) of these processes, and continue practicing what they are good at every day. As a result, each product is actually handcrafted by not one karigar but many. People in Saharanpur have always been working with wood. More than four lakh people are directly or indirectly involved in this craft, which still thrives on daily wages.

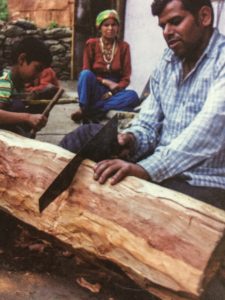

In Uttarakhand, there are more than 3 dozen types of different species of wood that have been used for constructing houses, doing ornamental work, and carving agricultural implements and domestic products. The ancestral houses and temples of Uttrakhand were constructed from wood and stone. Access to these forests for produce hence was filled superstitions and taboos.

Some of the best examples of wood-carving in West Bengal are found in the pillars, brackets, beams, and rafters of traditional chandimantaps, village community halls which are the centers of rural culture. The carvings are floral and geometric. The roof was covered with the local golden grass reeds bound together in geometric patterns by cane to hide the bamboo framework. Examples of chandimantaps are at Atpur and Sripur-Balagarh in Hooghly district and Ula-Balagarh in Nadia district. The raths of Bengal are made of wood decorated with carved panels of floral or geometrically sculptured figures and a pair of wooden horses. The carvings and figures are in folk style for the raths, while those for the chandimantaps are in the classical style. Carved wooden images are seen in many village temples and domestic shrines. Among these carved figures, folk gods and goddesses are almost as numerous as the classical figures. Even figures carved in the classical tradition have a simple but expressive folk style. The figures are painted in symbolic colours and the images are carved in neem or bel wood. Sutradhar craftpersons of Kalna in Burdwan traditionally make huge platters and bowls in many interesting shapes hewn out of a large block of mango wood. In a few villages in the Howdah and 24 Parganas districts there are both Muslim and Hindu wood-carvers who specialize in fine carving; they make delicately carved wooden panels and decorative furniture in teak, sisam and mahogany. Except for the semi-tribal group of karangas, who make turned wood items in the Susunia Hapania forest region of Bankura district, there is no tradition of wood- turning in West Bengal.

The large number of temples in Kerala and the doors, windows, and ceilings of most ancient taravads or ancestral homes show the high level of craftsmanship prevalent in wood-carving. The wood used is mainly deep-brown teak. These elegant taravads are the ancestral homes of the Nair community and are built in a specific pattern around a central courtyard called nalukettu. The rooms have massive teak doors, studded with brass. Rich carvings are found in the archways of these doors and the ceilings have scenes from religious epics, as well as flowers, foliage and animal motifs. A lot of sculptural and relief work is found as part of wood work done there. The motifs found in the woodwork are Puranic scenes and depictions from the epics, along with human figures, animals, birds, trees, and flowers. Rathas or temple chariots used during certain ceremonies showcase the artistry and technical mastery of the craftspersons of Kerala. Painting on wood is found in Kerala, especially in churches which are rich in wood carvings. Wood-carving is a highly evolved craft in Kerala, and the best examples are seen in the temples and churches. The tools used include the Kanupmattam - right angle Chinderam, planars, traditional bow and drill, chisels - flat, half rounded, V shaped and pointed; files - flat file, half round file and V shaped file and the saw. One of the richest examples of wood-carving is the Mahadeva temple in Katinakulam near Trivandrum. The ceiling is beautifully carved with Brahma, the god of creation, sitting on a swan in the centre. Elephant carving is also a specialisation here and elephants are produced in a variety of postures and sizes. Products include fluted coloumns topped by ornamental capitals, carved lintels, latticed shutters and slatted panels door and window shutters, brackets resembling stylized floral forms or composite animals, statuary, lion headed joists ,relief carved panels, wooden ceilings divided into panels, bearing a relief carved motif of a lotus, deity or dikpala, guardians of the cardinal directions; Idols and Decorative artifacts. Produced mainly in Chakai, Muttathhara, Manachaud, Palkulangara, Poonthura, Kulathoor, Karamana, Kurmampura, Vazhutacaud,Vellandad in Thiruvananthapuram district

The wood craft of Dharmsala is based on the Tibetan craft of wood carving. The products made include interiors of homes, architectural elements, statues, altars, boxes and musical instruments. The wood usually used are the khari, chilpine and other softwoods; the selection of the wood to be used is based on its plasticity, ease in carving and durability. The painting, lacquering and varnishing of the wood is an equally specialized task with its distinct colour scheme and style of Buddhist monasteries. The tools used are traditional and made locally from the bamboo fret saw, the bah, that is used to remove wood along the drawn pattern . with hammers, mallets, fine chisels and files.

Although less than five percent of the country's land is under forests, the material available to Pakistan's wood-craftsmen is of considerable variety. While the forests of mangrove-like trees in the coastal areas mostly provide firewood, date palms, babul (acasia arabica), farash, kikar and papal (ficus religiosa) scattered all over the sandy plains have traditionally yielded raw material for wood-craftsmen. In the hill tracts of Balochistan and the Northern Areas are found fruit trees and forests of deodar, pines, walnut, oaks, birch and willows. But by far the largest source of wood are the irrigated plantations of shisham (dabergia sirsco) and mulberry. The shisham plantations vary from large forests in Chhangamanga and Chichawatni (Sahiwal district) to rows of trees along the roads and watercourses. For each variety a different craft has been evolved.

THE CRAFT OF has long been extant in this region due to the. This huge cluster in Kirt Nagar with over 50,000 to 60,000 craftsmen engaged in crafting wood furniture was set up in 1975 by the Delhi government as a jungle of sagwan wood grew here providing the raw material needed for the craft. Working in workshop on an assembly line craftsmen specialize in executing a particular stage of the craft process whether it be the designing and transferring the farma pattern image onto the wool, or carving.

An unusual feature is that the craftsmen sell the products in an unfinished and un-polished form thereby any faults or discrepancies in the wood or workmanship can easily be identified. This furniture is then polished, finished, upholstered and sold by upmarket showrooms. The craftsmen specialize in ornate carvings on Chairs, Tables, Side tables, Beds, Cupboards, Sofas, etc

Other areas in Delhi where carving and carpentry skills are available is in Panchkuian Road and Jail Road

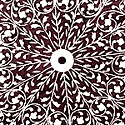

Wood inlay is the process of decorating the surface of wood by setting in pieces of material such as ivory, bone, plastic, or wood of different colours. This craft is concentrated in Mysore and Bangalore in Karnataka where its roots can be traced back to a family by the name of Mirza Yousuf Ali who were pioneers in the field. The artisan smoothens the base of the rose wood and the design is traced and etched into the surface. The several components of the inlay are painstakingly assembled to match and fit exactly into the grooves and are then glued in. The design is finished by obtaining the required shades with several coats of polish. Examples of inlay work in Karnataka include the ivory inlay in rose wood and ebony in the Srirangapatnam mausoleum; the doors of the Amba Vilas palace in Mysore are also fine examples of inlay. Products with inlay include plates, boxes, bowls, cigarette cases, and figures of animals, especially elephants, which continue to be popular. The designs include floral and geometric patterns, landscapes, pastoral scenes, processions, and scenes from the epics.

Punjab has its own wood work centers and each one has its own distinct style. Hoshiarpur, Jalandhar, Amritsar, and Bhera are known for their furniture and the carving is low relief with geometrical, floral, and animal designs. In Hoshiarpur, wood inlay work is done and the wood used is shisham or black wood, both as ground wood and with inlay. The articles made are tea pots, boxes, trays, table legs, screens, bowls, and chess boards. A popular and traditional product of Punjab is the pidhi, a wooden frame with an inside seat of woven jute sutli or cotton threads, twisted or untwisted. The designs are geometrical and the motifs are incorporated by weaving techniques. The normal height of a pidhi is 6 inches to 8 inches. With modern innovations they are raised in height, and made similar to a chair.

The wood inlay craftsmen in the beginning used ivory for the inlay work but ivory has now been replaced with bone. Plastic, different woods, shell and acrylic are also being used.

Wood is first seasoned and the design drawn on it with a pencil. The pattern is engraved onto the wood and the designs are carved out.

The acrylic sheets or whatever inlay material is to be used are cut carefully as per the design and after that set into the carved recess of the base wood with a mixture of adhesive and sawdust.

Beautiful metal inlay with brass or copper wires is also done. After inlay the surface of the wood is leveled and a thin layer of beeswax is applied to the surface in order to give it smoothness and gloss.

Intricately carved jewelry boxes, and other decorative and utilitarian items are crafted. Traditional techniques of decorative wood work, carving, inlaying, turning, and lacquering are being applied now to high-quality furniture and accessories.

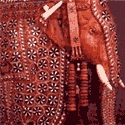

There are many palaces in Rajasthan where the doors are inlaid with ivory in intricate floral or geometric patterns. The same craftsmanship is found in thrones, howdahs, and horse or camel saddles. Mirror-inlay work on wood is of Persian origin. Here the glass is blown by the craftsperson at the site of decoration and while it is still hot mercury is poured in to mirror the concave insides. Then the blown mirror-glass is broken into small pieces and shaped according to the pattern drawn on the wooden wall. These are fixed with plaster or lime.