Wood Lac Craft of Etikoppaka, Andhra Pradesh,

Etikoppaka – a small, dusty village with a population of 12,000 in the Vishakhapatnam district is known for its wooden laccoloured objects. Practiced from many generations, this craft historically documented since the 1830s can be taken back to the time of the Bahmani sultanate. Etikoppaka craft has persisted and survived great hardships and its journey till today speaks volumes about the resilience of this craft form. In the post-independence period, shrinking local demand and low prices resulted in the migration of artisans to urban areas in search of mere jobs. It is even said that out of a total 225 weaving families, there was a time when only one old artisan and his wife were left in Etikoppaka. Post 1990, the introduction of synthetic dyes led to the initial distortion of traditional practices considered essential for the craft. The use of natural dye extracted from the now extinct local tree called Divi-Divi (Caesalpiniacoriaria) for tones of red, formed an important part in the production process. In the early years of the 20th century in the midst of hardships and the inevitable extinction of this craft, one man saw immense potential and took up the challenge of reviving Etikoppaka. C V Raju – the head of the local landowning family took a keen interest in the local craft of lathe turned and lacquered wood. His efforts to revive the eco-friendly wood-lacquer process with a focus on natural dyes and efficient processes has brought the artisans back to life who are said to have shifted back to their original craft based occupation. Approximately 200 artisans belonging to VishwaBrahmin, Devanga, Gouda, Padmasali, Konda, Settybaliga and Kapu castes practice this craft. Lac and AnkudiKarra (Wrightiatinctoria) or Ankudu wood form the main raw materials used in the Tharini or the turned wood lacquer process. Ankudu wood comes from a soft tree also known as soft ivory-wood grown abundantly in the local forests. Branches and trunks of the tree are used to create different objects. The application of Lac was introduced by C V Raja. Lac is a resinous substance used to impart colour to the wood. There are two types of lac known as Rangeen and Kusumi, where the latter is considered to be of superior quality. The tools used are basic and consist of a planer, saw, cutting tools and hand drills. The wood is seasoned and cut to suitable length. The lac sticks are used to lacquer the items. The lac is further oxidized with natural vegetable colour and then applied to the carved wood piece turning on a lathe.Mogalireku (kevda leaf) is used for finishing and flair to the product. Lacquer work is an extensive process and can be performed either by lathe, machine or hand. Revival of the craft was again led to the identification and use of various natural and vegetable dyes with available colours ranging from previously available tone red to ochre, olive, turquoise and indigo blue. Etikoppaka originally consisted of wooden articles made for domestic and religious use. Moreover, toys, mythological figures and carvings are said to be exquisite belonging to the Etikoppaka craft. To tap the market potential, various home décor and decorative items like ornaments, cups, lamps, bangles, jewellery boxes, photo frames, cutlery, table ware, and oil bottles form some of the recent and popular products. These products have also found a good market overseas. Efficient technology and application of traditional methods have resulted in steady improvement of the Etikoppaka craft. However, to say that the problems surrounding the Etikoppaka artisans have diminished would be fallacious. Stringent export norms, eroded markets with cheaper non-original copies of Etikoppaka are some of the issues which require attention. Moreover, inadequate supply of wood threatens to weaken the stability of the artisans. The forest department imposes a fine on the artisans if wood is obtained directly and thus, the artisans remain dependent on middlemen and vendors. Awareness of the craft has led to various institutions of fine art of Andhra Pradesh, NID, and NIFT to get involved in the designing and further development of Etikoppaka craft. Moreover, various societies such as Padmavati Associates, EtikoppakaVanaSamrakshanaSamiti (Forest protection committee) continue to work towards preserving and conserving the existing and future wood stock required for Etikopakka.

Etikoppaka – a small, dusty village with a population of 12,000 in the Vishakhapatnam district is known for its wooden laccoloured objects. Practiced from many generations, this craft historically documented since the 1830s can be taken back to the time of the Bahmani sultanate. Etikoppaka craft has persisted and survived great hardships and its journey till today speaks volumes about the resilience of this craft form. In the post-independence period, shrinking local demand and low prices resulted in the migration of artisans to urban areas in search of mere jobs. It is even said that out of a total 225 weaving families, there was a time when only one old artisan and his wife were left in Etikoppaka. Post 1990, the introduction of synthetic dyes led to the initial distortion of traditional practices considered essential for the craft. The use of natural dye extracted from the now extinct local tree called Divi-Divi (Caesalpiniacoriaria) for tones of red, formed an important part in the production process. In the early years of the 20th century in the midst of hardships and the inevitable extinction of this craft, one man saw immense potential and took up the challenge of reviving Etikoppaka. C V Raju – the head of the local landowning family took a keen interest in the local craft of lathe turned and lacquered wood. His efforts to revive the eco-friendly wood-lacquer process with a focus on natural dyes and efficient processes has brought the artisans back to life who are said to have shifted back to their original craft based occupation. Approximately 200 artisans belonging to VishwaBrahmin, Devanga, Gouda, Padmasali, Konda, Settybaliga and Kapu castes practice this craft. Lac and AnkudiKarra (Wrightiatinctoria) or Ankudu wood form the main raw materials used in the Tharini or the turned wood lacquer process. Ankudu wood comes from a soft tree also known as soft ivory-wood grown abundantly in the local forests. Branches and trunks of the tree are used to create different objects. The application of Lac was introduced by C V Raja. Lac is a resinous substance used to impart colour to the wood. There are two types of lac known as Rangeen and Kusumi, where the latter is considered to be of superior quality. The tools used are basic and consist of a planer, saw, cutting tools and hand drills. The wood is seasoned and cut to suitable length. The lac sticks are used to lacquer the items. The lac is further oxidized with natural vegetable colour and then applied to the carved wood piece turning on a lathe.Mogalireku (kevda leaf) is used for finishing and flair to the product. Lacquer work is an extensive process and can be performed either by lathe, machine or hand. Revival of the craft was again led to the identification and use of various natural and vegetable dyes with available colours ranging from previously available tone red to ochre, olive, turquoise and indigo blue. Etikoppaka originally consisted of wooden articles made for domestic and religious use. Moreover, toys, mythological figures and carvings are said to be exquisite belonging to the Etikoppaka craft. To tap the market potential, various home décor and decorative items like ornaments, cups, lamps, bangles, jewellery boxes, photo frames, cutlery, table ware, and oil bottles form some of the recent and popular products. These products have also found a good market overseas. Efficient technology and application of traditional methods have resulted in steady improvement of the Etikoppaka craft. However, to say that the problems surrounding the Etikoppaka artisans have diminished would be fallacious. Stringent export norms, eroded markets with cheaper non-original copies of Etikoppaka are some of the issues which require attention. Moreover, inadequate supply of wood threatens to weaken the stability of the artisans. The forest department imposes a fine on the artisans if wood is obtained directly and thus, the artisans remain dependent on middlemen and vendors. Awareness of the craft has led to various institutions of fine art of Andhra Pradesh, NID, and NIFT to get involved in the designing and further development of Etikoppaka craft. Moreover, various societies such as Padmavati Associates, EtikoppakaVanaSamrakshanaSamiti (Forest protection committee) continue to work towards preserving and conserving the existing and future wood stock required for Etikopakka.

Wood Lac Turnery/ Lac Abru/Cloud Work of Kutch, Gujarat,

Kutch is well known for its crafting of wood and lac turnery which is undertaken by a semi-nomadic community of lathe turners and carpenters called the Meghwals and Maniars. An indigenous lathe is used to turn and shape wood. It is then embellished with a vegetable colors and lac. Articles such as mortar and pestle, rolling pins, legs of tables and cots, cabinet and chests, dandia(sticks used in local dances etc are produced by the craftspeople. The tools employed for the crafting process are axe, wooden axle and lathe and iron bar support etc. Lac is obtained from an insect called kerria lacca and is in a resinous state. Amidst the rich heritage of art and craft in Gujarat, lac is another popular craft that has been produced across centuries. It is mainly used to make jewellery such as bangles, earrings and jewellery boxes, along with other decorative pieces. Gujarat's lac work on bangles is exquisitely embellished with various precious and semi-precious stones. They are famous for there embellishments and vibrant, exotic colours.

Kutch is well known for its crafting of wood and lac turnery which is undertaken by a semi-nomadic community of lathe turners and carpenters called the Meghwals and Maniars. An indigenous lathe is used to turn and shape wood. It is then embellished with a vegetable colors and lac. Articles such as mortar and pestle, rolling pins, legs of tables and cots, cabinet and chests, dandia(sticks used in local dances etc are produced by the craftspeople. The tools employed for the crafting process are axe, wooden axle and lathe and iron bar support etc. Lac is obtained from an insect called kerria lacca and is in a resinous state. Amidst the rich heritage of art and craft in Gujarat, lac is another popular craft that has been produced across centuries. It is mainly used to make jewellery such as bangles, earrings and jewellery boxes, along with other decorative pieces. Gujarat's lac work on bangles is exquisitely embellished with various precious and semi-precious stones. They are famous for there embellishments and vibrant, exotic colours.

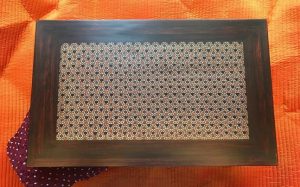

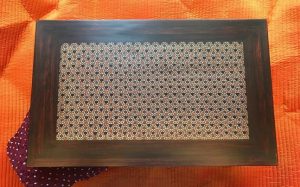

Wood Marquetry of Gujarat,

Surat is known for marquetry called sadeli. Thin and long strips of ebony, ivory, red wood, bone, and tin are stuck together to make the design. This craft was at one time used to ornament the doors of palaces and mansions; now it is also used to decorate wooden articles, especially boxes. This is not inlay work, but more in the nature of appliquè and involves no carving.

Surat is known for marquetry called sadeli. Thin and long strips of ebony, ivory, red wood, bone, and tin are stuck together to make the design. This craft was at one time used to ornament the doors of palaces and mansions; now it is also used to decorate wooden articles, especially boxes. This is not inlay work, but more in the nature of appliquè and involves no carving.

Wood Match-Stick Crafts of Gujarat,

The process involves making a long belt of match sticks prepared by using fevicol. Thereafter the belt is cut in the required shape, i.e., doors, ceilings, windows, pillars, stairs, etc. These small pieces are moulded by giving light pressure by hand. Finally, all small pieces are fixed with fevicol in the desire shape. The cost of raw material is minimal but the entire process is very labour intensive and requires high level of skill for making such masterpieces.

Wood Patch Work of Karnataka,

This is a very popular craft in Karnataka and is widely practised. Rosewood inlay work is done using wood shavings of various shades and hues; chips or shavings obtained when elaborate woodwork is done is used for the craft. The pattern is traced into a piece of rosewood suitable in suitably shape and size. Then wood chips in differing shades of brown, yellow and beige are used to fill in the pattern. Elements requiring other hues are created by painting directly on to the picture. This wood collage is assembled very carefully as the chips chosen have to be inset neatly. The whole picture is then given a veneer of polish, making it rich and glossy. The themes found in wood patchwork include rural scenes, historical depictions, religious figures, deities and vivid examples of nature in all its scenic beauty.

This is a very popular craft in Karnataka and is widely practised. Rosewood inlay work is done using wood shavings of various shades and hues; chips or shavings obtained when elaborate woodwork is done is used for the craft. The pattern is traced into a piece of rosewood suitable in suitably shape and size. Then wood chips in differing shades of brown, yellow and beige are used to fill in the pattern. Elements requiring other hues are created by painting directly on to the picture. This wood collage is assembled very carefully as the chips chosen have to be inset neatly. The whole picture is then given a veneer of polish, making it rich and glossy. The themes found in wood patchwork include rural scenes, historical depictions, religious figures, deities and vivid examples of nature in all its scenic beauty.

Wood Products and Wooden Furniture,

Wood-carving has, traditionally, been the forte of the Nepali artisan - using the most primitive of tools they have, over the centuries, endowed the simplest of products with great aesthetic appeal without detracting from their utilitarian value.

Wood-carving has, traditionally, been the forte of the Nepali artisan - using the most primitive of tools they have, over the centuries, endowed the simplest of products with great aesthetic appeal without detracting from their utilitarian value.

DAILY-USE PRODUCTS

Most daily use wooden products are crafted by scooping out the wood with traditional tools. Hollowed out objects like the canoe, mortar, theki (wooden containers for yogurt and sour milk), singmang (container for clarified butter), chauntho (oil container), gauwa (milk container), and ari bowls are been crafted from the wood of the pine and cedar. Lathe machines have been introduced recently for the making of hollowed and cylindrical objects. These are then smoothened with sand-paper and given several coats of varnish to make the surface smooth and shiny. However, some of the hollow wooden objects like the theki, singmang, and chauntho, as well as wooden mortars and bowls, are being replaced with plastic and aluminium products.

- Theki: In carving a theki, a log of wood, preferably cedar, is rotated horizontally and a curved tool is used to slice the wood. As the log of wood rotates, it is scooped little by little. After the required depth is cut, it is refined further and the exterior portion is also cut, giving it the required shape. Thekis come in different sizes with little variation in their shape. They are used for preparing and churning the yogurt.

- Singmang: It is believed that clarified butter or ghee can be kept in a singmang for several years without any preservative.

- Ari: Bowls or ari made of wood are used in making pickles. Any edible item can be kept in such bowls.

FURNITURE, CHESTS, & BOXES

Soft-wood - like chanp (champac), pine, and cedar - is used in Nepal to make furniture, chests, and boxes. Sisso variety of wood is preferred for carving because of its beautiful grain. Chests made of soft-wood were a traditional wedding gift from the parents to the bride. These traditional chests are slowly being replaced by modern metal almirahs or cupboards/wardrobes.

Carved wooden furniture and chests are given a coating of turpentine oil or a mixture of light coloured rosin obtained from the pine trees to highlight the designs.

PROBLEMS & INTERVENTIONS

Traditional craftsmen are now affected by the scarcity of wood due to deforestation. The hard sal wood of the southern plains is rapidly being depleted. Although afforestation programmes have been launched, the requirement of wood far outstrips the supply.

LOCATIONS

Most of the wood-carving is done in Lalitpur and in the Kathmandu Valley.

Wood Turning – Shagzo,

The Bhutanese produce a variety of highly prized utilitarian turned wooden bowls, cups, plates, dishes and containers, all of which they use in their daily life. These bowls and containers come in different shapes, sizes, and colours, which distinguish the different uses that each is put to - a monk's bowl, a serving bowl, a rice bowl, or a soup bowl being common examples. Made from wood with the help of slow-revolving, pedal-operated lathes, these bowls remain unaffected by heat or liquid and are lacquered with indigenous materials. Often, the smaller tea or soup bowls may be inlaid with silver, which makes them even more attractive and also enhances their lasting ability.

The Bhutanese produce a variety of highly prized utilitarian turned wooden bowls, cups, plates, dishes and containers, all of which they use in their daily life. These bowls and containers come in different shapes, sizes, and colours, which distinguish the different uses that each is put to - a monk's bowl, a serving bowl, a rice bowl, or a soup bowl being common examples. Made from wood with the help of slow-revolving, pedal-operated lathes, these bowls remain unaffected by heat or liquid and are lacquered with indigenous materials. Often, the smaller tea or soup bowls may be inlaid with silver, which makes them even more attractive and also enhances their lasting ability.

RAW MATERIALS

The lush forests of Bhutan have provided craftsmen through the centuries with a rich source of hard, semi-hard, and soft wood required to prepare functional and decorative products. The woods used include the chellum, etometo or rhododendron, maple, and kushing.

Lac, extracted from the Rhus succedanea tree is used for finishing the turned wood articles.

PRACTITIONERS & LOCATIONS

These articles are mainly produced in the Tashi Yangtse region of eastern Bhutan.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

Wooden bowls and receptacles are turned on foot-powered treadle lathes. The lathe is operated manually with the feet. Two people work simultaneously - one to shape and the other to operate the lathe.

Some bowls and all receptacles are lacquered black or red with a substance extracted from the Rhus succedanea. This is the same substance that the Japanese use for lacquer, but in Bhutan the finishes are less sophisticated. Bhutanese lacquering is applied manually with the thumb. To obtain a high-quality finish, the process is repeated six to seven times; four or five applications are used to impart a medium-quality finish and two or three applications are done for functional articles of that are not particularly good in quality.

Bowls lined with silver are used only for butter-tea or alcohol. Wooden receptacles are used as serving dishes for food and also as plates by the heads of the household.

PRODUCT RANGE

- Thokey: Fruit BowlA traditional article, that is used during religious ceremonies and on special occasions.

- Tsamdeg: Serving Bowl with LidThe Tsamdeg was originally used for tsampa (barley or wheat flour)The product originated in the north and extreme east of Bhutan where roasted wheat and barley flour comprised the staple diet.

- Baw Dapa: Rice Plate with Lid The Baw dapa with a lid is traditionally used to serve rice in. The dapa is 10 inches in diameter and has a lid. It is used especially by lamas, monks, and dignitaries.

- Dumchem Dapa: Rice Plate with LidThis wooden round container with a lid is traditionally used to serve rice in.

- Gophor: Cup with Lid The gophor is traditionally used for drinking liquids like tea and soup.

- Laphor: Bowl with Lid The laphor is traditionally used by the monastic community, for tea and soup.

- Boephor: Cup The beophor is traditionally used for drinking wine, curry, or tea. People carry it on their persons, saving their host from having to provide cups when serving liquid refreshment. Men carried two cups wrapped in cloth plus a knife at the waist, while women carry one cup. It is wiped or washed with warm water.

- Za Phob: Burl Cup It is the Bhutanese ceremonial cup of wooden burl with natural lacquer used to drink tea and wine in.

- Samden: This is 1" height and 1"foot broad and is used for serving snacks in.

The prices of the products depend on the quality of wood used, the quality of the lacquer finish, and the presence or absence of silver mounting.

CONTEMPORARY TRENDS

Of late, under royal patronage, bowls are being made of ivory inlaid with silver. The availability of wooden bowls is rather limited, since production skills have traditionally been confined to a few centres in the country. The government has initiated steps for large-scale production of wooden bowls by training more people in the craft at the Uchu village in Paro, one of the traditional centres. Because of their attractive shapes and colours they are a favourite with tourists and have immense potential for export.

Wood Work – Shingzo,

As with all the zorig chusum, shingzo is a devotional act, which links the craftspeople to their personal deities. For centuries houses, palaces, dzongs, temples, bridges and utilitarian items for the home and the field have been and continue to be made of a combination of stone, rammed earth, bamboo and local timber or wood. Timber is used lavishly in all structures for windows, doors, stairs, balconies, columns, beams and other structural elements and for elaborate decorative cornices. It is this lavish use of timber, which gives Bhutanese architecture its beauty, elegance and unique character at the same time making these structures highly vulnerable to fire and degeneration.

As with all the zorig chusum, shingzo is a devotional act, which links the craftspeople to their personal deities. For centuries houses, palaces, dzongs, temples, bridges and utilitarian items for the home and the field have been and continue to be made of a combination of stone, rammed earth, bamboo and local timber or wood. Timber is used lavishly in all structures for windows, doors, stairs, balconies, columns, beams and other structural elements and for elaborate decorative cornices. It is this lavish use of timber, which gives Bhutanese architecture its beauty, elegance and unique character at the same time making these structures highly vulnerable to fire and degeneration.

The techniques used by the craftspeople have remained relatively unchanged and even today the basic constructional elements for the building of a house are made by hand with the help of a few tools only. Buildings are not constructed according to a set floor plan but at the same time follow measurements dictated by the sacred scriptures. The carpenters plan and prepare the necessary building elements based on an understanding of the sacred texts and supervise the work when the construction begins. Massive Dzongs, Lhakhangs and Gompas, palaces, houses - some of which are built on mountain tops, sheer cliff faces, at strategic places -are erected without either a floor plan and most remarkably without iron, not even nails.

Common to every structure are the intricate decorations, woodcarvings and brightly coloured patterns and murals on wall panels. Carvings of Lord Buddha and various other deities adorn the walls and altars of temples and shrines. The common motifs on more secular buildings are the druk (dragon), Tashi - Tagye and various legendary animals (refer article on symbols). The upper stories of a building boast remarkable woodwork with paintings seen frequently on the frames of the three lobed windows and on the ends of beams. Elaborately painted timber cornices are usually placed around the upper edges of the structure, just below the roof and above doors and windows. Windows and doors are also normally painted giving the houses a very festive appearance. Floral, animal and religious motifs are mainly used as themes for the colourful paintings.

Timber is used for flooring, doors, windows, beams and ceilings in houses. Doors and windows are generally carved with traditional motifs. Very narrow timber window are found on the lower floors and larger elaborately painted timber three lobed windows on the top floor. Roofs are of made of wooden shingles kept in place with small stones. Large open breezy spaces under the high, shingled roofs, create the unique 'flying roof' characteristic, which is peculiar to indigenous Bhutanese houses. A single log of wood with ledges cut on one side serves as a staircase. Almost every house has a wooden altar with statues of the Buddha and the great gurus.

Wood Work of Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh,

Wood work is largely practiced in Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh. Products such as architectural elements, cupboards, statues, altars, picture frames, boxes, musical instruments etc are created under this craft from. Tools such as bamboo fret saw called bah, wooden mallet, sharpening stone called jamdar, chisels, gouges, metal pointer, calipers, template, files and sandpaper are needed for the production process.

Wood work is largely practiced in Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh. Products such as architectural elements, cupboards, statues, altars, picture frames, boxes, musical instruments etc are created under this craft from. Tools such as bamboo fret saw called bah, wooden mallet, sharpening stone called jamdar, chisels, gouges, metal pointer, calipers, template, files and sandpaper are needed for the production process.

Wooden Block Craft of Hand Printing of West Bengal,

The block makers' village is in Bora about 15 kms from Serampore, off the GT Road. Serampore is about 25 kms from Kolkata to the North, on the west bank of the Hooghly. Earlier known as Fredericknagore it is one of the few places in India that was colonized by Denmark from 1756 to 1845.

The block makers' village is in Bora about 15 kms from Serampore, off the GT Road. Serampore is about 25 kms from Kolkata to the North, on the west bank of the Hooghly. Earlier known as Fredericknagore it is one of the few places in India that was colonized by Denmark from 1756 to 1845.

Wooden Block Making for Hand Printing in Pethapur, Gujarat,

Though the origins of block carving are lost in the folds of history, we have examples of block printed fabric dating back to 2000 B.C. Evidence has been found that the art of dyeing fabrics was practiced in the Indus Valley Civilisation. According to the 1961 Census conducted by the Government of India, the craft was developed and specialised by the Suthar artisans who were traditionally carpenters. The document also mentions that the craft might have been adopted from Iran at the time of the Mughals and concentrated in Shikarpur in Sindh from where it spread to Gujarat. This is in keeping with the theory that the skill of block printed fabrics travelled from Sindh to the modern Indian states of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Western Madhya Pradesh. The block makers of Pethapur believe that many centuries ago, women got tired of their white unembellished clothes and began using their bangles dipped in colour to pattern their garments. The carpenters noticed and decided to provide the women with various designs and so gave rise to the tradition of hand block printing on textiles. Most of the craftsmen engaged in this work belonged to the Gajjar Suthar caste who believe that their ancestors settled in Pethapur some 200 years ago. The caste believes it is the progeny of Vishvakarma, the architect of the gods1. Like the hand block printers, block making is an endangered craft. These talented craftsmen, similar to so many other craftspersons in India, face the problem of situating themselves within the contemporary market economy, in attempting to create and develop products which might curb the widening divide between greater supply and diminishing demand. The block makers had a few prominent clusters in Pilakhuwa, Farukhabad and Ahmedabad which supplied the printers of the country. It is from Ahmedabad that the block carvers migrated to Pethapur, which today is the only remaining centre in the country solely making wooden blocks. It supplies to all the hand block printing communities from Sanganer (Rajasthan) to Bagh (Madhya Pradesh). In other centres, Pilakhuwa for instance, the block makers have applied their carving techniques to making wooden tables, boxes, photo frames, pen holders etc to broaden their market and continue their trade. Pethapur, situated 40 kilometres from Ahmedabad, is the only surviving centre of wood block carving. Blocks are ordered and sold directly between the printer and carver with no middlemen or agents. Either the block maker travels to the printing centre with his directory of designs on which orders are taken or the printer goes to the carver, either ordering from the block makers design repertoire or giving his own design layout.

1 Census of India 1961:7.

After tracing the design onto the (kaplo), narrow grooves are carved with chisels, flat in case of a geometric pattern and pointed for floral motifs. Strips or wires are then fixed in the carved grooves or dots as the case may be. These blocks are durable as they don't chip while cleaning as often happens with wooden blocks. They are mostly in demand by larger factories that mass produce goods.

Though the origins of block carving are lost in the folds of history, we have examples of block printed fabric dating back to 2000 B.C. Evidence has been found that the art of dyeing fabrics was practiced in the Indus Valley Civilisation. According to the 1961 Census conducted by the Government of India, the craft was developed and specialised by the Suthar artisans who were traditionally carpenters. The document also mentions that the craft might have been adopted from Iran at the time of the Mughals and concentrated in Shikarpur in Sindh from where it spread to Gujarat. This is in keeping with the theory that the skill of block printed fabrics travelled from Sindh to the modern Indian states of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Western Madhya Pradesh. The block makers of Pethapur believe that many centuries ago, women got tired of their white unembellished clothes and began using their bangles dipped in colour to pattern their garments. The carpenters noticed and decided to provide the women with various designs and so gave rise to the tradition of hand block printing on textiles. Most of the craftsmen engaged in this work belonged to the Gajjar Suthar caste who believe that their ancestors settled in Pethapur some 200 years ago. The caste believes it is the progeny of Vishvakarma, the architect of the gods1. Like the hand block printers, block making is an endangered craft. These talented craftsmen, similar to so many other craftspersons in India, face the problem of situating themselves within the contemporary market economy, in attempting to create and develop products which might curb the widening divide between greater supply and diminishing demand. The block makers had a few prominent clusters in Pilakhuwa, Farukhabad and Ahmedabad which supplied the printers of the country. It is from Ahmedabad that the block carvers migrated to Pethapur, which today is the only remaining centre in the country solely making wooden blocks. It supplies to all the hand block printing communities from Sanganer (Rajasthan) to Bagh (Madhya Pradesh). In other centres, Pilakhuwa for instance, the block makers have applied their carving techniques to making wooden tables, boxes, photo frames, pen holders etc to broaden their market and continue their trade. Pethapur, situated 40 kilometres from Ahmedabad, is the only surviving centre of wood block carving. Blocks are ordered and sold directly between the printer and carver with no middlemen or agents. Either the block maker travels to the printing centre with his directory of designs on which orders are taken or the printer goes to the carver, either ordering from the block makers design repertoire or giving his own design layout.

1 Census of India 1961:7.

Tools

Ari / Karvat (saw)

Bhido (vice)

Dismis (screw driver)

Farsi (chisel)

Ghodi (wooden stand)

Gotilo/ Thapdi (mallet)

Hathodi (hammer)

Kanas (file)

Pakad (pliers)

Panch (punch)

Randho (carpenters plane)

Shardi (wooden drill)

Shighro (vice)

Tankanu (graver/ chisel)

Vansalo (adze)

Raw Material

Wood

Khadi (chalk)

Tracing Paper

Coloured Pencils

Process

The wood is bought in an open market. The most common wood is teak (sag) or (sag saghwan) preferred because of its durability and resistance to termites and decay. It is locally known as (sag2 patli). Despite its durability, the wood is soft and easy to carve. It is also fibreless so especially suitable for fine work. It is bought from the forests of Southern Gujarat.

When bought the wood is in uneven pieces called (wadh). It is stored in a dark enclosed space for up to one year. Once the wood is ready the edges are shaped with the saw, chisel and adze to give it the desired shape - oblong, square or round, depending on the design. The surface to be carved is filed and smoothened by grinding on a rough stone on which is spread fine river sand and water. The shaped smoothened block is known as (kaplo.

The (kaplo) is now ready for the design to be traced on its surface and carved. For any design two types of blocks are carved today: the main block with the outline called (rekh) and the subsidiary or relative blocks for each colour called (data3). They are both carved in relief.

The smoothened surface is coated with the layer of white chalk to aid definition and visibility of the traced design.

The design is first drawn on paper. This paper is fixed to the whitened surface of block, held in place with nails. Using a fine tipped or pointed chisel the design is perforated onto the block.

Once the design is traced onto the block, the negative spaces are carved or gouged using a variety of different shaped and sized chisels. If the spaces to be removed are vast, a hand drill is used. Once the block has been carved the block makers finish by engraving a nail shaped point, (mokh), on the right hand corner of the block. This enables the printer to precisely align the blocks while printing.

The four sides of the block are sloped, narrow at the top slanting outwards at the base where the design is carved. In the case of dense designs such as floral patterns or closely carved designs holes are drilled through the block to allow trapped air to release and thus ensure air bubbles don't smudge the print or spread the colour. These air passages are called (pavan-sar).

The handle (chhado) is either carved from the block or attached later. The first is more durable and also more expensive.

After the carving is complete and the block is ready it is placed in groundnut oil for a couple of days to season the wood and protect it from climatic changes and moisture. This ensures the block doesn't warp through repeated use. It takes up to three days to carve a block set of an intricate design.

|

|

|

BRASS BLOCKS

An alternative technique to carving in wood is blocks where the designs are created by attaching metal wires or strips to a wooden base. Such blocks are almost always (rekhs) and save the labour of carving the main block. |

Conclusion

The future of the block carvers of Pethapur is uncertain. It is entirely possible that they will follow the other block making traditions and apply their skill to making products which have a wider and also urban market. This would ensure the continuity of the knowledge but it would be unfortunate if in the process the beautiful hand printed fabrics which India has been renowned for since the beginning of civilization become extinct.

2Tectona Grandis or Indian Oak. 3The Census of India of 1961 refers to the data blocks as datla 1970:14

2Tectona Grandis or Indian Oak. 3The Census of India of 1961 refers to the data blocks as datla 1970:14

Wooden Comb and Hair Ornaments of Andhra Pradesh/Telangana,

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Wooden Comb and Hair Ornaments of Assam,

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Wooden Comb and Hair Ornaments of Meghalaya,

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Wooden Comb and Hair Ornaments of Tamil Nadu,

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Wooden Comb and Hair Ornaments of Uttar Pradesh,

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Wooden Comb and Hair Ornaments of West Bengal,

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Before plastic was introduced in India, combs were made of wood, bamboo, metal, bone, and ivory. Whether simple in design or an intricate work of art, comb-making was a hereditary craft. Now the craft product is viewed as an object of curiosity and decorative value rather than as an object of everyday use. The share of the market controlled by wooden comb-makers has dwindled and they are now focusing on crafting hair ornaments and pins, along with intricately carved spoons, ladles, and other items of cutlery. This hereditary craft uses tools that are crafted by the artisans themselves with the help of an ironsmith. The wood used for a quality comb is deodar, ebony, or any other strong wood that is locally available. The wood is cleaned and given its outer shape with the help of a file. The piece is gripped firmly with the feet; the seating posture resembles an inverted lid with its three sides raised by about 6 inches to 8 inches with a nail strategically positioned as a hold for the foot. The finishing file is double layered, with one of the layers having sharply serrated edges and the second layer serving as a moving measure to mark the length of the comb while the teeth are being sawed. A special file is used to smoothen the teeth. No pencils or markers are used, no designs are drawn, and the designs are made entirely in free hand. A simple wooden comb takes about an hour to make, while a complicated and intricately designed one can take up to three days. A comb that is regularly used lasts only for a month, thereby ensuring regular employment to the comb-maker. The wide-toothed side is meant to be used before the narrow side to prevent the teeth from breaking. An interesting and ingenious product is the oil dispensing comb in which oil is poured in through a central aperture open at the top of the spine. When the aperture is filled with oil, the opening is closed firmly. When the comb is used this oil comes out evenly from tiny holes in the teeth and the hair is thus oiled and combed at the same time.

Wooden Cutlery of Udayagiri, Andhra Pradesh,

Udaygiri in Nellore district known for its wooden cutlery and wooden salad bowls, continues a tradition that is about 150 years old. The mostly commonly used material for making the kitchen items are nardi wood, devadari, bikki chakka and kaldi chakka. The object is designed with the help of drill and finishing is achieved through files. The smaller items like spoons and paper knifes and key chains by nardi and bikki wood. Bigger spoons and forks are made out of harder wood called kaldi. These cutleries were commonly used to serve curry and rice. The common products include sets of forks and spoons, paperknives, glasses, key chains and hair clips.

Udaygiri in Nellore district known for its wooden cutlery and wooden salad bowls, continues a tradition that is about 150 years old. The mostly commonly used material for making the kitchen items are nardi wood, devadari, bikki chakka and kaldi chakka. The object is designed with the help of drill and finishing is achieved through files. The smaller items like spoons and paper knifes and key chains by nardi and bikki wood. Bigger spoons and forks are made out of harder wood called kaldi. These cutleries were commonly used to serve curry and rice. The common products include sets of forks and spoons, paperknives, glasses, key chains and hair clips.

Wooden Lac craft of Punjab,

Wooden Lacquer ware in Punjab is practiced mainly in three centers now - Hoshiarpur, Batala Quadian in Batala district and Jullunder. Each known for its own speciality. Earlier Punjab was known for the cloud work locally called abri on wood. In this, on a yellow coating the surface to be lacquered is touched intermittently with a red stick. The stick makes an irregular colored pattern as it revolves, around which a black border is drawn. The interstices are then filled with white to produce a cloud effect. Several variations were possible. Amritsar and Jalandhar were well known for their lacquered furniture with bold and pronounced designs. Legs for beds, divans, and purple colored lac boxes were made here. The work is now mainly done in Jullunder in the nakashi style where the surface is engraved using needles so that the design shows up in a variety of colors. This layered lac-coating of Jalandhar uses different colors from those of Hoshiarpur thus distinguishing further between them. The kharadi, lathe turner community of Hoshiarpur make turned wooden furniture, ornamented with motifs etched on to the lac coating. Different components of the furniture are turned on power lathes and the rotating pieces are coated with multiple layers of lac after which a sharp metal stylus is used to etch motifs, revealing the underlying colors. Earlier purple lac was popular but has now fallen into disuse. With white, black and red popularly used now and coated on to the turned wood in the same order of coloring. Yellow is occasionally added as well though usually only three layers of color are used. With experimentation there are new colors using white on a reddish base. And other such variations. The products include boxes, chairs, containers, the low stool/Peedi and other objects.

Wooden Lacquer ware in Punjab is practiced mainly in three centers now - Hoshiarpur, Batala Quadian in Batala district and Jullunder. Each known for its own speciality. Earlier Punjab was known for the cloud work locally called abri on wood. In this, on a yellow coating the surface to be lacquered is touched intermittently with a red stick. The stick makes an irregular colored pattern as it revolves, around which a black border is drawn. The interstices are then filled with white to produce a cloud effect. Several variations were possible. Amritsar and Jalandhar were well known for their lacquered furniture with bold and pronounced designs. Legs for beds, divans, and purple colored lac boxes were made here. The work is now mainly done in Jullunder in the nakashi style where the surface is engraved using needles so that the design shows up in a variety of colors. This layered lac-coating of Jalandhar uses different colors from those of Hoshiarpur thus distinguishing further between them. The kharadi, lathe turner community of Hoshiarpur make turned wooden furniture, ornamented with motifs etched on to the lac coating. Different components of the furniture are turned on power lathes and the rotating pieces are coated with multiple layers of lac after which a sharp metal stylus is used to etch motifs, revealing the underlying colors. Earlier purple lac was popular but has now fallen into disuse. With white, black and red popularly used now and coated on to the turned wood in the same order of coloring. Yellow is occasionally added as well though usually only three layers of color are used. With experimentation there are new colors using white on a reddish base. And other such variations. The products include boxes, chairs, containers, the low stool/Peedi and other objects.