Aashavali Brocade of Ahmedabad, Gujarat,

Aashaval or as better known today as Ahmedabad is the hub of brocade weaving. Under the Mughals, brocades from Ahmedabad and Surat were considered of the best quality. The use of zari, gold or silver thread wrapped around a silk core, was very popular and a range of textiles made of gold and silver were created in Gujarat. Aashwali and kinkhab textiles are the most famous from the state. Newer materials like plastic zari, rayon are used. The most common motifs on aashavali saris are stylised versions of parrots, peacock, paisley and human figures. [gallery ids="177939,177940,177941,177942"]

Aashaval or as better known today as Ahmedabad is the hub of brocade weaving. Under the Mughals, brocades from Ahmedabad and Surat were considered of the best quality. The use of zari, gold or silver thread wrapped around a silk core, was very popular and a range of textiles made of gold and silver were created in Gujarat. Aashwali and kinkhab textiles are the most famous from the state. Newer materials like plastic zari, rayon are used. The most common motifs on aashavali saris are stylised versions of parrots, peacock, paisley and human figures. [gallery ids="177939,177940,177941,177942"]

Agate Stone Craft of Cambay, Gujarat,

The existence of Agate mines at Ratnapur and Rajpipla date back to A.D. 77. Cambay is best known for shaping agate stones and the method of processing agates used by the artisans here still surpasses that of their overseas competitors. The stones are broken into the required pieces, and these pieces are heated, chiseled, bleached, and surfaced. The finishing touch is given by polishing. The artisans craft jewellery like ear rings, nose rings, bangles, and necklaces, along with buttons, trays, ashtrays, and paperweights.

The existence of Agate mines at Ratnapur and Rajpipla date back to A.D. 77. Cambay is best known for shaping agate stones and the method of processing agates used by the artisans here still surpasses that of their overseas competitors. The stones are broken into the required pieces, and these pieces are heated, chiseled, bleached, and surfaced. The finishing touch is given by polishing. The artisans craft jewellery like ear rings, nose rings, bangles, and necklaces, along with buttons, trays, ashtrays, and paperweights.

Ahir Embroidery of Gujarat,

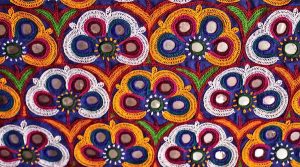

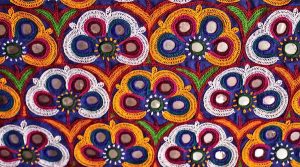

Introduction: Gujarat can be divided into three main regions; mainland of Gujarat, Kathiawad region of Saurashtra, and desert regions of Kachchh. The Kachchh area is mostly populated by the nomadic and pastoral communities. Kachchh forms a meta-cluster in which nineteen identified clusters are located. Kachchh is eco-diversified region with mangroves, grassland, marshlands, Little Rann and Gulf of Kachchh. This region of Gujarat is inhabited by many communities who once migrated from places like Sindh, Baluchistan and even Afghanistan almost five centuries ago. The Ahir community of Kachchh region has a distinctive craft style that is deeply rooted in the community life style. The utilitarian products of community are adorned by women in embroidery. The stitched products mark the tangible aspects of dowries. Thus the embroidery forms an important activity practised to make dowry gifts by the community and also as sign of group identity, marital status, etc. Community: Ahir is one of the many tribes of Kachchh region who under the patronage by royal family found their own distinctive style of embroidery. Like Rabari, Bhanushali, Meghwal and others they are pastoral communities or nomadic sheep herders who settled in Kachchh. Ahir, the name finds its origin from Sanskrit word Abhira, which means fearless. They identify themselves as Gopas or herdsmen who came with Krishna to Dwarka and followed the Gop culture. Stitches: It is style distinguished by its tiny mirrors, surrounded by minutely detailed medallions worked with geometric motifs. Using bright yellow, orange, black and red, the pattern is placed in grid arrangement. Sankli or chain stitch for outlining and vana or herringbone stitch used for filling along with bakhiya and dana serving the purpose of filling and detailing the motifs and designs. This gamut of stitches comprises the Ahir embroidery. The inter weaning space is covered with the chain stitch and the buttonhole stitch, which is a straight thread crossed at right angles many times over. Products: The embroidery forms an integral part of the culture where the Ahir women adorn torans, chaklas, quilts, cushions and belts etc. The roundness of the motifs by using repetitive circular mirrors is distinct to Ahir tribe.

Ahir is a historical pastoral tribe of India spreading across Kutch and Saurashtra in Gujarat. Ahir women wear embroidered skirt ad the kapaa or kanjari with a hed veil. The kanjari is full covered in mirror work and the making is known to be very time consuming and tedious. Ahir embroidery is identified as superior in design and aesthetic. It has a good balance of motifs and embroidery. The embroidery is outlined with the open chain stitch executed in yellow or white yarn.

Ahir is a historical pastoral tribe of India spreading across Kutch and Saurashtra in Gujarat. Ahir women wear embroidered skirt ad the kapaa or kanjari with a hed veil. The kanjari is full covered in mirror work and the making is known to be very time consuming and tedious. Ahir embroidery is identified as superior in design and aesthetic. It has a good balance of motifs and embroidery. The embroidery is outlined with the open chain stitch executed in yellow or white yarn.

Introduction: Gujarat can be divided into three main regions; mainland of Gujarat, Kathiawad region of Saurashtra, and desert regions of Kachchh. The Kachchh area is mostly populated by the nomadic and pastoral communities. Kachchh forms a meta-cluster in which nineteen identified clusters are located. Kachchh is eco-diversified region with mangroves, grassland, marshlands, Little Rann and Gulf of Kachchh. This region of Gujarat is inhabited by many communities who once migrated from places like Sindh, Baluchistan and even Afghanistan almost five centuries ago. The Ahir community of Kachchh region has a distinctive craft style that is deeply rooted in the community life style. The utilitarian products of community are adorned by women in embroidery. The stitched products mark the tangible aspects of dowries. Thus the embroidery forms an important activity practised to make dowry gifts by the community and also as sign of group identity, marital status, etc. Community: Ahir is one of the many tribes of Kachchh region who under the patronage by royal family found their own distinctive style of embroidery. Like Rabari, Bhanushali, Meghwal and others they are pastoral communities or nomadic sheep herders who settled in Kachchh. Ahir, the name finds its origin from Sanskrit word Abhira, which means fearless. They identify themselves as Gopas or herdsmen who came with Krishna to Dwarka and followed the Gop culture. Stitches: It is style distinguished by its tiny mirrors, surrounded by minutely detailed medallions worked with geometric motifs. Using bright yellow, orange, black and red, the pattern is placed in grid arrangement. Sankli or chain stitch for outlining and vana or herringbone stitch used for filling along with bakhiya and dana serving the purpose of filling and detailing the motifs and designs. This gamut of stitches comprises the Ahir embroidery. The inter weaning space is covered with the chain stitch and the buttonhole stitch, which is a straight thread crossed at right angles many times over. Products: The embroidery forms an integral part of the culture where the Ahir women adorn torans, chaklas, quilts, cushions and belts etc. The roundness of the motifs by using repetitive circular mirrors is distinct to Ahir tribe.

Ahir is a historical pastoral tribe of India spreading across Kutch and Saurashtra in Gujarat. Ahir women wear embroidered skirt ad the kapaa or kanjari with a hed veil. The kanjari is full covered in mirror work and the making is known to be very time consuming and tedious. Ahir embroidery is identified as superior in design and aesthetic. It has a good balance of motifs and embroidery. The embroidery is outlined with the open chain stitch executed in yellow or white yarn.

Ahir is a historical pastoral tribe of India spreading across Kutch and Saurashtra in Gujarat. Ahir women wear embroidered skirt ad the kapaa or kanjari with a hed veil. The kanjari is full covered in mirror work and the making is known to be very time consuming and tedious. Ahir embroidery is identified as superior in design and aesthetic. It has a good balance of motifs and embroidery. The embroidery is outlined with the open chain stitch executed in yellow or white yarn.

Aipan/Ritual Floor Painting of Almora, Uttarakhand,

Aipan is a traditional decorative wall or floor art form of Kumaon. This art form has a great degree of social, cultural and religious significance associated with it. It is taught to the daughters and the daughters-in-law of the family, hence passing the tradition from generation to generation. Aipan is drawn on the walls and floor where religious ceremonies are to be performed. Traditionally, every morning, aipan is freshly made on the threshold. Some aipan patterns are drawn to appease a particular God or Goddess. For the Kumaonis, each deity in the Hindu pantheon has a special symbol and every occasion is celebrated with an aipan of a different kind. The raw materials used for this craft are, geru (red clay), rice paste, abheer gulal, turmeric, dhatura flowers, burnt coconut shell. These raw materials are easily available at the local stores in the area. The artist, which is mainly the woman of the family, draws the pattern freehand, from memory. The central part, which is considered to be ceremonial and has a prescribed motif, is drawn in rice paste using the ring finger, anamika. The outer part, which is decorative is then drawn, adjusted to fit an important element without which the aipan is considered unfinished. The aipan drawn on the floor of the prayer room and on the deity's seat or chowki is defined by Tantric motifs, called peeth or yantra. The lines and dots in an aipan have metaphorical meanings, for instance, an aipan for a dead person is drawn without dots on the 12th day. After three days it is rubbed out with mud and a new one with dots is made. Thresholds are decorated with good luck patterns, which are many times just vertical white lines.

Aipan is a traditional decorative wall or floor art form of Kumaon. This art form has a great degree of social, cultural and religious significance associated with it. It is taught to the daughters and the daughters-in-law of the family, hence passing the tradition from generation to generation. Aipan is drawn on the walls and floor where religious ceremonies are to be performed. Traditionally, every morning, aipan is freshly made on the threshold. Some aipan patterns are drawn to appease a particular God or Goddess. For the Kumaonis, each deity in the Hindu pantheon has a special symbol and every occasion is celebrated with an aipan of a different kind. The raw materials used for this craft are, geru (red clay), rice paste, abheer gulal, turmeric, dhatura flowers, burnt coconut shell. These raw materials are easily available at the local stores in the area. The artist, which is mainly the woman of the family, draws the pattern freehand, from memory. The central part, which is considered to be ceremonial and has a prescribed motif, is drawn in rice paste using the ring finger, anamika. The outer part, which is decorative is then drawn, adjusted to fit an important element without which the aipan is considered unfinished. The aipan drawn on the floor of the prayer room and on the deity's seat or chowki is defined by Tantric motifs, called peeth or yantra. The lines and dots in an aipan have metaphorical meanings, for instance, an aipan for a dead person is drawn without dots on the 12th day. After three days it is rubbed out with mud and a new one with dots is made. Thresholds are decorated with good luck patterns, which are many times just vertical white lines.

Ajanta Paintings of Maharashtra,

The Ajanta paintings at Aurangabad are ancient cave paintings showcasing the history of Buddhism. There are 29 rock-cut caves which date back to 2nd century BC. This is a UNESCO world heritage site and a popular tourist destination. It is protected monument under the care of Archealogical survey of India.

The Ajanta paintings at Aurangabad are ancient cave paintings showcasing the history of Buddhism. There are 29 rock-cut caves which date back to 2nd century BC. This is a UNESCO world heritage site and a popular tourist destination. It is protected monument under the care of Archealogical survey of India.

Ajrakh Hand Block Printing of Sind, Pakistan,

The Ajrakh process of Block Printing has been an art practised for several centuries in Sind. This traditional craft still remains the most popular in Sind and is apparently the only process least spoiled by modern methods during the past centuries. This process is a long, arduous task involving the use of 27 chemicals and consisting of approximately 16 various steps in methods. The traditional Ajrakh procss of Block Printing remians the most popular in Sind, the colours generally used on indigenous designs being deep blue, maroon and black. Block printed material in Punjab exhibit vibrant colours on patterns more contemporary.

The Ajrakh process of Block Printing has been an art practised for several centuries in Sind. This traditional craft still remains the most popular in Sind and is apparently the only process least spoiled by modern methods during the past centuries. This process is a long, arduous task involving the use of 27 chemicals and consisting of approximately 16 various steps in methods. The traditional Ajrakh procss of Block Printing remians the most popular in Sind, the colours generally used on indigenous designs being deep blue, maroon and black. Block printed material in Punjab exhibit vibrant colours on patterns more contemporary.

Alleppey Coir of Kerala,

Coir yarn has been produced since time immemorial throughout the coastal belt of Kerala. It is reported that ancient travellers like Megasthenes took back many valuable gifts including coir rope from the Malabar Coast. Coconut fibre is extracted from the shell of the coconut by dehusking, retting and beating. The husks are first separated from the nuts and then retted in lagoons for up to ten months. The retted husks are then manually beaten with wooden mallets to produce the golden fibre. Thereafter, the fibre is spun into yarn on traditional spinning wheels called “ratts”. The yarns are then dyed in the required colours and woven to make different products including coir mats, rugs, tiles, baskets and suchlike. The coir is also used in many other ways, for example fish nets, plant climbers as well as for industrial, agricultural and domestic purposes.

Coir yarn has been produced since time immemorial throughout the coastal belt of Kerala. It is reported that ancient travellers like Megasthenes took back many valuable gifts including coir rope from the Malabar Coast. Coconut fibre is extracted from the shell of the coconut by dehusking, retting and beating. The husks are first separated from the nuts and then retted in lagoons for up to ten months. The retted husks are then manually beaten with wooden mallets to produce the golden fibre. Thereafter, the fibre is spun into yarn on traditional spinning wheels called “ratts”. The yarns are then dyed in the required colours and woven to make different products including coir mats, rugs, tiles, baskets and suchlike. The coir is also used in many other ways, for example fish nets, plant climbers as well as for industrial, agricultural and domestic purposes.

Allo Textiles – Himalayan Giant Nettle,

Fibres from the Himalayan giant nettle (Girardinia diversifolia), locally known as allo, have been extracted for use in Nepal for hundreds of years - this extraction and use continues till today. Because of its size the allo plant is also referred to as hati sisnu, or elephant nettle. The bark fibre has been extracted, spun and woven for centuries by the Magars, Tamangs, Gurungs, the nomadic Rautye, and especially the Rais. This most unusual of form of textile has been used for ropes, sacks, bags, head bands, mats, fishing nets, and clothing for as long as anyone can remember.

Fibres from the Himalayan giant nettle (Girardinia diversifolia), locally known as allo, have been extracted for use in Nepal for hundreds of years - this extraction and use continues till today. Because of its size the allo plant is also referred to as hati sisnu, or elephant nettle. The bark fibre has been extracted, spun and woven for centuries by the Magars, Tamangs, Gurungs, the nomadic Rautye, and especially the Rais. This most unusual of form of textile has been used for ropes, sacks, bags, head bands, mats, fishing nets, and clothing for as long as anyone can remember.

TRADITIONS

This allo plant has, for long, provided the raw material for making a large proportion of the textiles needed by the household, including clothing, mats, sacks, bags, fishing-nets, ropes, carry, and head bands. All the weaving, including that of clothing, mats, sacks, and bags, is traditionally the preserve of the women, while fishing nets, ropes, and head bands are made by the men. In the past, allo textiles were bartered for grain in times of food shortage. Allo fishing-nets, porters' headbands, sacks, bags, and mats are still in demand and in regular use.

RAW MATERIAL

The allo (Girardinia diversifolia) plant grows in most northern parts of Nepal and is also found in the hills from the west to the east of the country at altitudes ranging between 1,200m and 3,000 m. It flourishes under the shade of deciduous forests, and in moist, sandy soils, especially ravines; it can also be found on shrub land and on the edges of cultivated land, where it is used to consolidate bunds on terraced land. Growing to a height of 3 m, the thorn-covered stem, which contains the fibres, can measure up to 4 cm in diameter at the base. The plant has long, white thorns that have a very nasty sting, the effect of which lasts for about half-an-hour or so.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

Although there are variations in weaving techniques in different parts of Nepal, the basic methods of allo harvesting and spinning remain similar all over.

Harvesting begins towards the end of the monsoon season in August-September, and continues till March when the plants begin to flower. The villagers, both men and women, spend up to a week in the jungle collecting the bark. The best-quality fibre comes from the early harvests. Allo weavers believe that allo growing under shade yields the finest and whitest fibres, while plants that are more exposed to the sun are brownish in colour. Fibres from plants growing at high altitudes are the most valued for weaving.

Only mature, thick stems are harvested; others are left to seed. The stems are cut using sickles (hasias) at about 15 cm from the ground in order to leave sufficient stem for new shoots to sprout. The stinging thorns on both stems and leaves make the cutting of the stems hazardous and the harvesters protect their hands with bundles of cloth. Often, the stems are left for a few days before fibre extraction begins - this is done to reduce the potency of the stinging hairs. On an average, in one day, the bark of about 370 stems are harvested. The fresh bark of one allo stem can weigh up to 100 grams - it yields a maximum of 5 grams of dry fibre.

The bark is left to dry for a few weeks. The dried bark is then boiled with wood ash for about four to five hours to make it soft and to extract the fibre. Then it is washed with white mica clay soil (kamero mato) to lubricate the fibres and make their separation and spinning easier. Finally, the strands of fibre are hung-up and sun-dried. The surplus mica soil is dusted off before weaving,. During weaving - to prevent the allo yarn from getting fluffy - the weaver occasionally brushes the warp with water, using a shelled maize cob as a brush.

Traditionally, all allo cloth was woven on back-strap or body-tension looms, the women using a lightweight hand-spindle, about 40 cm long. Spindles and looms are standard equipment of every home. Weaving takes place mainly during winter when no fieldwork is done. With the minimum of simple components this type of loom fulfils the basic function of keeping the warp threads under tension while the weft thread is interwoven with them at right angles. All parts of the loom, except the wooden beater, are carved from bamboo at home. Though spinning by hand-spindle is slower than spinning on a wheel, the spindle has the advantage of weighing very little, being easily carried and used anywhere. Allo fibres are taken on most journeys and are spun not only when resting but even when walking. When the weaving is completed or at the end of the day, the loom parts can just be rolled together into a bundle, which is easily stored in the roof rafters.

INNOVATIONS

Traditional methods of spinning the yarn using a hand-spindle are still in use, though innovations in technique, materials, and equipment have resulted in giving this craft a big boost. Many changes have been introduced in the past few decades in processing, dyeing, weaving, and knitting. The adoption of a new type of allo cloth in which the traditional gimte pattern was woven with an allo warp and a wool weft, created a new market opportunity.

A warping-mill and two sturdy frame looms were adopted by some weavers, especially for heavy weight cloth and for creating a greater width than was available earlier. The twill and diamond patterned weave were also tried successfully with an allo warp. Twill allo cloth - and especially allo and wool tweed - found an immediate local market. Allo mats, based on traditional weaving and also cloth with cotton warp and allo weft, found a ready market among visitors and tourists.

New techniques of finishing have also been adopted by the weavers, The allo tweed cloth is first burled so that all knots and loose warp threads are mended, after which the cloth is washed and 'wet' finished by trampling with the feet in a thick soapy solution until it felts and shrinks to a prescribed measurement. It is then thoroughly rinsed and rolled onto a slatted drying roller.

PRODUCT RANGE

In recent years, traditional weaving of allo cloth has been on the increase. This warp-faced weave has a very firm texture which is needed for the jackets and waistcoats made from it - which offer protection against the cold - and for bags and sacks - which have to stand up to a lot of wear and tear.

The traditional allo jacket (phenga) of the Rais - with and without sleeves - is worn by men, women, and children. These jackets are beautifully embroidered with the embroidery serving the dual purpose of providing decoration as well as strengthening joints and seams.

Allo bags (jholas) in natural shades, from beige to brown, are valued for their strength and durability. The bag is carried over the head with the strap resting above the forehead, thus leaving both hands free.

Allo sacks are stronger and more durable than jute ones. Coming in sizes of about 58 cm X 108 cm, these sacks are usually made from a single piece.

Several products other than the traditional have been added on to the weavers' repertoire - these include bags, wallets, place mats, and clothing and are popular with the tourist and export market. The weaving of these allo textiles have become a valuable source of supplementary income.

Alpana/Floor Decorations,

The art of floor painting is a personal, individual offering to the gods through a medium which has generated an extravagant array of motifs and patterns. The canvas is the floor of the home and the material used is obtained from the kitchen shelves. This ritual art for wish fulfilment and protection is practised by women through the year and with special devotion during festival time. Immersed in ancient ritualistic practices, the alpana has become a common form of decoration and is today an integral part of Bangladeshi culture. Alpana or alipana is an indigenous word, deshaju meaning the art of drawing ali (embankment or wall). From primitive times alpanas have been a part of the magic-religious practice of brata, a vow observed by women for the fulfilment of a cherished desire. Each brata has its own alpana, which at the time of its performance is drawn on the ground with rice powder paste. Drawn freehand, the alpana must clearly depict the object the bratee (devotee) desires, otherwise its result will be nullified. Assigned and bound in its enclosure, the woman draws motifs symbolising her wishes and at a given time and place she invokes the blessings of the power that works in heaven and on earth. There are said to be over seventy bratas with their numerous presiding deities. The quality of art is secondary in importance to the symbols and objects drawn as the meaning and the desire supersedes the decorated and artistic element.

The art of floor painting is a personal, individual offering to the gods through a medium which has generated an extravagant array of motifs and patterns. The canvas is the floor of the home and the material used is obtained from the kitchen shelves. This ritual art for wish fulfilment and protection is practised by women through the year and with special devotion during festival time. Immersed in ancient ritualistic practices, the alpana has become a common form of decoration and is today an integral part of Bangladeshi culture. Alpana or alipana is an indigenous word, deshaju meaning the art of drawing ali (embankment or wall). From primitive times alpanas have been a part of the magic-religious practice of brata, a vow observed by women for the fulfilment of a cherished desire. Each brata has its own alpana, which at the time of its performance is drawn on the ground with rice powder paste. Drawn freehand, the alpana must clearly depict the object the bratee (devotee) desires, otherwise its result will be nullified. Assigned and bound in its enclosure, the woman draws motifs symbolising her wishes and at a given time and place she invokes the blessings of the power that works in heaven and on earth. There are said to be over seventy bratas with their numerous presiding deities. The quality of art is secondary in importance to the symbols and objects drawn as the meaning and the desire supersedes the decorated and artistic element.

Angora Fiber of Uttarakhand,

Angora rabbit breeding and production was a state-sponsored project and is administered by the Uttarakhand Sheep and Wool Development Board. Angora is a specialty fiber that fetches high rates in the market. It was felt that the fiber would render fresh impetus to the wool-based economy of the northern districts of Uttarakhand, which are the backbone of the traditional wool based cottage industry.

Angora rabbit breeding and production was a state-sponsored project and is administered by the Uttarakhand Sheep and Wool Development Board. Angora is a specialty fiber that fetches high rates in the market. It was felt that the fiber would render fresh impetus to the wool-based economy of the northern districts of Uttarakhand, which are the backbone of the traditional wool based cottage industry.

Ankik Gudhna/Tattoos of Chhattisgarh,

Tattooing is done all over the body by the tribal's of Chhattisgarh who tattoo different motifs. There are various rules pertaining to tattooing --- for instance, tattooing is forbidden on the hips and the waist. Tattoo motifs also reflect tribal occupation and tools; there are many motifs related to agriculture and cattle-breeding. The scene of Sita Rasoi, the Kitchen of Sita, from the epic Ramayana is a popular tattoo among many tribal groups. The scorpion, honey-bee, hen, horse, and mare are the motifs of fertility. The tattooing starts at the age of seven, is done at puberty, and then just before marriage (for a girl). Tattooing is done mainly by the women. The tattooing ink is prepared by mixing soot with bhilava (ipmoea digitais) oil. The motifs are first drawn out on the body and then etched on to the skin by pricking with a needle and ink. The tribal's prepare the ink by burning the skin of snakes and mixing it in niger seed oil. These tattoo designs are now duplicated on paper.

Tattooing is done all over the body by the tribal's of Chhattisgarh who tattoo different motifs. There are various rules pertaining to tattooing --- for instance, tattooing is forbidden on the hips and the waist. Tattoo motifs also reflect tribal occupation and tools; there are many motifs related to agriculture and cattle-breeding. The scene of Sita Rasoi, the Kitchen of Sita, from the epic Ramayana is a popular tattoo among many tribal groups. The scorpion, honey-bee, hen, horse, and mare are the motifs of fertility. The tattooing starts at the age of seven, is done at puberty, and then just before marriage (for a girl). Tattooing is done mainly by the women. The tattooing ink is prepared by mixing soot with bhilava (ipmoea digitais) oil. The motifs are first drawn out on the body and then etched on to the skin by pricking with a needle and ink. The tribal's prepare the ink by burning the skin of snakes and mixing it in niger seed oil. These tattoo designs are now duplicated on paper.

Ankik Gudhna/Tattoos of Madhya Pradesh,

Tattooing is done all over the body by the tribal's of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh who tattoo different motifs. There are various rules pertaining to tattooing --- for instance, tattooing is forbidden on the hips and the waist. Tattoo motifs also reflect tribal occupation and tools; there are many motifs related to agriculture and cattle-breeding. The scene of Sita Rasoi, the Kitchen of Sita, from the epic Ramayana is a popular tattoo among many tribal groups. The scorpion, honey-bee, hen, horse, and mare are the motifs of fertility. The tattooing starts at the age of seven, is done at puberty, and then just before marriage (for a girl). Tattooing is done mainly by the women. The tattooing ink is prepared by mixing soot with bhilava (ipmoea digitais) oil. The motifs are first drawn out on the body and then etched on to the skin by pricking with a needle and ink. The tribal's prepare the ink by burning the skin of snakes and mixing it in niger seed oil. These tattoo designs are now duplicated on paper.

Tattooing is done all over the body by the tribal's of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh who tattoo different motifs. There are various rules pertaining to tattooing --- for instance, tattooing is forbidden on the hips and the waist. Tattoo motifs also reflect tribal occupation and tools; there are many motifs related to agriculture and cattle-breeding. The scene of Sita Rasoi, the Kitchen of Sita, from the epic Ramayana is a popular tattoo among many tribal groups. The scorpion, honey-bee, hen, horse, and mare are the motifs of fertility. The tattooing starts at the age of seven, is done at puberty, and then just before marriage (for a girl). Tattooing is done mainly by the women. The tattooing ink is prepared by mixing soot with bhilava (ipmoea digitais) oil. The motifs are first drawn out on the body and then etched on to the skin by pricking with a needle and ink. The tribal's prepare the ink by burning the skin of snakes and mixing it in niger seed oil. These tattoo designs are now duplicated on paper.

Annibuta Sari of Andhra Pradesh,

These saris have a rich temple pallu and a traditional pit-loom is used to weave them. The entire sari, both the body as well as the tissue pallu, is woven through with rich temple designs. Extra gold thread is used for the weft and the tissue portions. The weaving involves a high level of skill and continuous practice is required to obtain perfection in the design.

These saris have a rich temple pallu and a traditional pit-loom is used to weave them. The entire sari, both the body as well as the tissue pallu, is woven through with rich temple designs. Extra gold thread is used for the weft and the tissue portions. The weaving involves a high level of skill and continuous practice is required to obtain perfection in the design.

Applique and Patch Work of Banni, Gujarat,

Appliqué is widely found in Gujarat where pieces of coloured and patterned fabrics in different sizes are sewn on to a plain background as a composite piece. This is mainly done on items of household use. The colours are brilliant, and the pieces are highly ornamented with motifs of animals and birds. In the Banni area of Sind, the embroidered work is often on maroon khaddar silk and the threads used are deep orange, golden yellow, dark red, and bright blue in colour. Octagonal motifs are often inset with mirrors. A traditional practice of layering worn and torn pieces of fabrics to recycle and strengthen them, appliqué and patchwork are practiced by women across the state. Applique is the art of applying fabric on fabric with the edges sewn down by hand stitches. Patchwork entails sewing little patches of geometric shaped fabric together to form a textile pattern. Traditionally the techniques were used to create gorgeous quilts for household use.

Appliqué is widely found in Gujarat where pieces of coloured and patterned fabrics in different sizes are sewn on to a plain background as a composite piece. This is mainly done on items of household use. The colours are brilliant, and the pieces are highly ornamented with motifs of animals and birds. In the Banni area of Sind, the embroidered work is often on maroon khaddar silk and the threads used are deep orange, golden yellow, dark red, and bright blue in colour. Octagonal motifs are often inset with mirrors. A traditional practice of layering worn and torn pieces of fabrics to recycle and strengthen them, appliqué and patchwork are practiced by women across the state. Applique is the art of applying fabric on fabric with the edges sewn down by hand stitches. Patchwork entails sewing little patches of geometric shaped fabric together to form a textile pattern. Traditionally the techniques were used to create gorgeous quilts for household use.

Applique and Patch Work of Odisha,

An important and traditional craft in Odisha, practiced in and around the town of Bhubaneswar, this involved the making of enormous appliqué canopies for Lord Jagannath, and his sister Subhadra and brother Balbhadra during the Rath Yatra. It involves the process of cutting coloured cloth into geometrical and figurative animal and floral motifs and stitching them onto a piece of cloth that can ultimately be converted to a product. The possibilities of usage of appliqué are endless --- temple canopies, lamp shades garden umbrellas, handbags, kitchen accessories, and bed and table linen are made The village of Pipli, close to Bhubaneswar is the center for some beautiful appliqué work. Puri in Odisha is also known for its appliqué craft. The traditional appliqué products revolved around temple activities and festivals, and thus included large and highly-decorated umbrellas, tents, and pavilions. Other centers for applique work in Odisha are Kanchana in Ganjam district and Cuttack district.

An important and traditional craft in Odisha, practiced in and around the town of Bhubaneswar, this involved the making of enormous appliqué canopies for Lord Jagannath, and his sister Subhadra and brother Balbhadra during the Rath Yatra. It involves the process of cutting coloured cloth into geometrical and figurative animal and floral motifs and stitching them onto a piece of cloth that can ultimately be converted to a product. The possibilities of usage of appliqué are endless --- temple canopies, lamp shades garden umbrellas, handbags, kitchen accessories, and bed and table linen are made The village of Pipli, close to Bhubaneswar is the center for some beautiful appliqué work. Puri in Odisha is also known for its appliqué craft. The traditional appliqué products revolved around temple activities and festivals, and thus included large and highly-decorated umbrellas, tents, and pavilions. Other centers for applique work in Odisha are Kanchana in Ganjam district and Cuttack district.

Applique and Patchwork Embroidery of Rajasthan,

The term ‘Applique’ is of French origin and it refers to a technique in which smaller pieces of fabric are sewed upon a larger piece of fabric to create a patchwork design. It is an ancient technique used to create various decorative and other useful items. One can see various items made through the Applique technique nowadays like wall hangings, bed sheets, purses, cushion covers, sitting mats, clothing, etc. It is a technique which is economical though being remarkably famous in every field of fashion and lifestyle. Sometimes worn out pieces of cloth can be used to create beautiful patterns. One can also see tents of nomadic people in deserts with elaborate applique work. Today artists also use mirrors, beads and other metallic pieces over applique work to enhance its beauty.

The term ‘Applique’ is of French origin and it refers to a technique in which smaller pieces of fabric are sewed upon a larger piece of fabric to create a patchwork design. It is an ancient technique used to create various decorative and other useful items. One can see various items made through the Applique technique nowadays like wall hangings, bed sheets, purses, cushion covers, sitting mats, clothing, etc. It is a technique which is economical though being remarkably famous in every field of fashion and lifestyle. Sometimes worn out pieces of cloth can be used to create beautiful patterns. One can also see tents of nomadic people in deserts with elaborate applique work. Today artists also use mirrors, beads and other metallic pieces over applique work to enhance its beauty.

Applique of Gujarat,

Applique of Kutch is coveted worldwide for its colourful and carefully stitched patchwork . Executed two ways- direct and reverse applique, the crafting process involves strips of various shapes to be sewn together to create fabrics which can be used a s quilts, hangings, canopies and long decorative friezes. These quilts form a significant component of the the dowry among the Meghwal, Sodha rajput, Halepotra, Mutwa and Jat and Rabari communities. Floral and animal motifs are employed to provide a sense of vitality to the finished piece. [gallery ids="176655,176656,176657,176658,176659"]

Applique of Kutch is coveted worldwide for its colourful and carefully stitched patchwork . Executed two ways- direct and reverse applique, the crafting process involves strips of various shapes to be sewn together to create fabrics which can be used a s quilts, hangings, canopies and long decorative friezes. These quilts form a significant component of the the dowry among the Meghwal, Sodha rajput, Halepotra, Mutwa and Jat and Rabari communities. Floral and animal motifs are employed to provide a sense of vitality to the finished piece. [gallery ids="176655,176656,176657,176658,176659"]

Applique Thangkas of Kangra, Himachal Pradesh,

Called Dras-drub-ma, the appliqué scroll thangkas serves a similar purpose to the painted Thanka but is crafted by stitching together pieces of shaped cloth onto a base fabric. To this is added embroidery to create the image required. in some cases the thangka may even be completely embroidered. These thankhas are created by only male Buddhists after training in the monasteries in the iconometry and iconography of the art including the colour scheme.

Called Dras-drub-ma, the appliqué scroll thangkas serves a similar purpose to the painted Thanka but is crafted by stitching together pieces of shaped cloth onto a base fabric. To this is added embroidery to create the image required. in some cases the thangka may even be completely embroidered. These thankhas are created by only male Buddhists after training in the monasteries in the iconometry and iconography of the art including the colour scheme.