Bhangra Cloth,

In the cold hill areas of Nepal the common nettle (chalne sisnu/ Urtica dioica) is processed and woven into cloth, blankets, sleeping bags, and ropes. This greyish, rough, and warm woven textile provides long years of hardy wear and tear.

In the cold hill areas of Nepal the common nettle (chalne sisnu/ Urtica dioica) is processed and woven into cloth, blankets, sleeping bags, and ropes. This greyish, rough, and warm woven textile provides long years of hardy wear and tear.

RAW MATERIAL

Bhangra cloth is made from the fibres of the common nettle or sisnu, a plant much smaller than the allo. The chalne sisnu or stinging nettle plants or grow wild to a height of up to 2 m and are found throughout the temperate regions of Nepal. The stem (about 0.5-1.0 cm in diameter) is downy and covered with stinging hairs.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

In September and October, the nettle stalks are cut in the forests, the leaves removed, and the outer bark peeled off. The bark is partially dried in the sun and boiled with ash in a big cauldron (taulo/ khadkaunlo). When the fibres are partially digested, they are beaten thoroughly with a wooden hammer or mugro over a flat stone slab. This process yields the soft, furry, grey fibres that resemble cotton. The fibre is dried in the sun and converted into yarn on a spinning wheel; the cloth is subsequently woven on a loom (tan).

Bhareva Shilp/Metal Craft of Madhya Pradesh,

The word 'bhareva' means 'one who fills' and the people who make objects by pouring a filling molten metal into moulds are called Bharevas. These craftspersons are found mainly in Betul district. The products made include utensils, bells, jingles, lamps, elephants, houses, Shiva lingams and bird figures.

The word 'bhareva' means 'one who fills' and the people who make objects by pouring a filling molten metal into moulds are called Bharevas. These craftspersons are found mainly in Betul district. The products made include utensils, bells, jingles, lamps, elephants, houses, Shiva lingams and bird figures.

Bhil Tribal Painting of Madhya Pradesh,

The Bhils- are a tribe native to the western and central region of India. They are the third largest tribal community in the states of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan and Maharashtra. The word Bhil is derived from the Dravidian word ‘vil’ mean the archer. They speak Bhilli which belongs to the Indo Aryan family of languages.

The Bhils- are a tribe native to the western and central region of India. They are the third largest tribal community in the states of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan and Maharashtra. The word Bhil is derived from the Dravidian word ‘vil’ mean the archer. They speak Bhilli which belongs to the Indo Aryan family of languages.

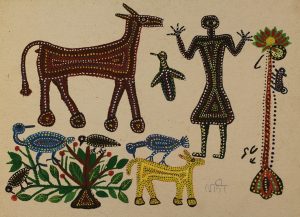

BHIL PAINTINGS

Like any other tribe, Bhils decorate their houses, walls, temples with paintings using vibrant colours. The paintings are done on mud walls which are first plastered with mud and cow dung. The figures drawn are mostly sacred and ritualistic. These paintings are drawn on various occasions like marriage ceremony, ritual ceremonies or festivals. Daily life scenarios are also depicted in these paintings. The purpose of these paintings lies in promoting fertility, avert diseases, propitiating gods, etc. Natural colours were used traditionally to produce brilliant paintings using turmeric, vegetable leaves, blackberries which would give yellow, green, blue, purple and so on. Artists also used rock or clay from their habitation and surrounding areas to make colours. Some Bhil artists are also experts at relief work, glass painting, mural works, emboss paintings etc. This give them a new medium to explore their self-expression. Raw materials were first crushed to make powder and then mixed with warm water to form a paste. Rice powder was also mixed with water to use it as paint. Twig of bamboo or neem is used as a painter’s brush for traditional painting. Nowadays, acrylic colours and synthetic brushes are used by young artists. The motifs are classified into nature-inspired motifs like sun, star, moon; geometric designs like dots, vertical and horizontal lines; Animal and bird motifs like cattle, snake, elephant, rat, tiger, peacock; and floral motifs like a leaf, flower, plants, and banyan tree.

Bhutanese Architecture,

For centuries houses, palaces, dzongs, temples, bridges and utilitarian items for the home and the field have been and continue to be made with local materials consisting of a combination of stone, rammed earth, bamboo and local timber or wood. Timber is used lavishly in all structures for windows, doors, stairs, balconies, columns, beams and other structural elements and for elaborate decorative cornices. The techniques used by the craftspeople have remained relatively unchanged and even today the basic constructional elements for the building of a house are made by hand with the help of a few tools only. Buildings are not constructed according to a set floor plan but at the same time follow measurements dictated by the sacred scriptures. The carpenters plan and prepare the necessary building elements based on an understanding of the sacred texts and supervise the work when the construction begins. Massive Dzongs, Lhakhangs and Goenpas, palaces, houses - some of which are built on mountain tops, sheer cliff faces, at strategic places - are erected without either a floor plan and most remarkably without iron, not even nails. Common to every structure are the intricate decorations, woodcarvings and brightly coloured patterns and murals on wall panels. Carvings of Lord Buddha and various other deities adorn the walls and altars of temples and shrines. The common motifs on more secular buildings are the druk (dragon), Tashi - Tagye and various legendary animals (refer article on symbols). The upper stories of a building boast remarkable woodwork with paintings seen frequently on the frames of the three lobed windows and on the ends of beams. Elaborately painted timber cornices are usually placed around the upper edges of the structure, just below the roof and above doors and windows. Windows and doors are also normally painted giving the houses a very festive appearance. Floral, animal and religious motifs are mainly used as themes for the colourful paintings. Ecologically sound local construction technology has developed in response to the

For centuries houses, palaces, dzongs, temples, bridges and utilitarian items for the home and the field have been and continue to be made with local materials consisting of a combination of stone, rammed earth, bamboo and local timber or wood. Timber is used lavishly in all structures for windows, doors, stairs, balconies, columns, beams and other structural elements and for elaborate decorative cornices. The techniques used by the craftspeople have remained relatively unchanged and even today the basic constructional elements for the building of a house are made by hand with the help of a few tools only. Buildings are not constructed according to a set floor plan but at the same time follow measurements dictated by the sacred scriptures. The carpenters plan and prepare the necessary building elements based on an understanding of the sacred texts and supervise the work when the construction begins. Massive Dzongs, Lhakhangs and Goenpas, palaces, houses - some of which are built on mountain tops, sheer cliff faces, at strategic places - are erected without either a floor plan and most remarkably without iron, not even nails. Common to every structure are the intricate decorations, woodcarvings and brightly coloured patterns and murals on wall panels. Carvings of Lord Buddha and various other deities adorn the walls and altars of temples and shrines. The common motifs on more secular buildings are the druk (dragon), Tashi - Tagye and various legendary animals (refer article on symbols). The upper stories of a building boast remarkable woodwork with paintings seen frequently on the frames of the three lobed windows and on the ends of beams. Elaborately painted timber cornices are usually placed around the upper edges of the structure, just below the roof and above doors and windows. Windows and doors are also normally painted giving the houses a very festive appearance. Floral, animal and religious motifs are mainly used as themes for the colourful paintings. Ecologically sound local construction technology has developed in response to the

- local topography

- climatic conditions

- cultural traditions and religious beliefs

MATERIALS

Traditionally houses, palaces, dzongs, lakhangs and goenpas, stupas or chortens, bridges and utilitarian items for the home and the field have been and continue to be made with local materials consisting of a combination of stone, rammed earth, bamboo and local timber or wood.

Stone:

Stone arts are used in the construction of the outer walls of large Dzongs, Lhakhangs, Goenpas, stupas or chortens, palaces, and other buildings.

Timber:

Wood, found abundantly in the country, is used lavishly for windows, doors, stairs, balconies, columns, beams, other structural elements and for elaborate decorative cornices, which are usually placed around the upper edges of the structure and just below the roof and above doors and windows. Very narrow timber window are found on the lower floors and larger elaborately painted timber three lobed windows on the top floor. Windows and doors are also normally painted giving buildings and houses a very festive appearance. Floral, animal and religious motifs are mainly used as themes for the colourful paintings.

Timber is also used for flooring and ceilings in houses. Roofs are of made of wooden shingles kept in place with small stones. Large open breezy spaces under the high, shingled roofs, create the unique 'flying roof' characteristic, which is peculiar to indigenous Bhutanese houses. A single log of wood with ledges cut on one side serves as a staircase.

Almost every house has a wooden altar with statues of the Buddha and the great gurus. Murals and carvings of Lord Buddha and various other deities adorn the walls and altars of temples and shrines.

ES OF CONSTRUCTION

Bhutanese architecture broadly consists of

- Large fortresses (Dzongs),

- temples (Lhakhangs) and monasteries (Goenpas),

- stupas (chortens)

- palaces

- vernacular housing

Bidri/Inlay on Metal of Andhra Pradesh,

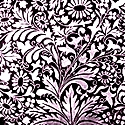

Bidri is a unique metalware technique found only in India. It is a form of encrusted metalware, where one metal is inlaid on to another. The beauty of bidriware lies in the striking contrast of colours, with the glossy silver inlay being set off by the matt black metal. The craft of bidriwork is believed to have originated in Bidar (Karnataka). It has since spread to other places like Hyderabad (Andhra Pradesh). Bidri products include a diverse range of products including huqqa bases, bowls, boxes, candle stands, trays, ashtrays, vases, jewellery, and buttons. The motifs vary from floral arabesques and intricately patterned leaves and flowers to geometric designs. The technical processes involved in the making of bidriware are complex and include casting, designing engraving, inlaying, blackening, and polishing. All these processes can be performed either by a single artisan or else different processes can be undertaken by different artisans, including a moulder, a designer, an engraver, and an inlayer. The item is first cast with the help of a mould of red clay into which a molten solution --- predominantly copper and zinc with smaller amounts of lead and tin --- is poured. The engraving tool, a kalam or metal chisel of varied shapes and points is used to engrave the designs, which are drawn in free hand. For the inlay, metal wires --- usually silver, but occasionally gold or brass --- are laid in the engraved area. Besides being visually striking, bidriwork is also enduring; it does not rust and looks the same for years to come.

Bidri is a unique metalware technique found only in India. It is a form of encrusted metalware, where one metal is inlaid on to another. The beauty of bidriware lies in the striking contrast of colours, with the glossy silver inlay being set off by the matt black metal. The craft of bidriwork is believed to have originated in Bidar (Karnataka). It has since spread to other places like Hyderabad (Andhra Pradesh). Bidri products include a diverse range of products including huqqa bases, bowls, boxes, candle stands, trays, ashtrays, vases, jewellery, and buttons. The motifs vary from floral arabesques and intricately patterned leaves and flowers to geometric designs. The technical processes involved in the making of bidriware are complex and include casting, designing engraving, inlaying, blackening, and polishing. All these processes can be performed either by a single artisan or else different processes can be undertaken by different artisans, including a moulder, a designer, an engraver, and an inlayer. The item is first cast with the help of a mould of red clay into which a molten solution --- predominantly copper and zinc with smaller amounts of lead and tin --- is poured. The engraving tool, a kalam or metal chisel of varied shapes and points is used to engrave the designs, which are drawn in free hand. For the inlay, metal wires --- usually silver, but occasionally gold or brass --- are laid in the engraved area. Besides being visually striking, bidriwork is also enduring; it does not rust and looks the same for years to come.

|

Anees Ahmed S/o late Mr.Ghanil Ahmed learned the craft of bidri from his father. According to the artisan the craft has been in practice for over 400 years created at the time of the Bahmani Dynasty. Even though Anees is a graduate his interest in the craft tradition led him to make bidriware his career. This has not been an easy decision to make and keep in the face of diminishing markets. Earlier in his area more than 10 families participated in the craft but today only 2 families remain while others have moved to more gainful employment. |

| Bidri is a manually intensive craft. It is a time consuming, and requires concentration and patience. And yet Anees claims that the joy he gets from his work makes him pursue it passionately despite the hardships and limitations. | |

| Hyderabad boasts of one of the finest forms of creativity- the Bidri craft. Of all the beautiful gold and silver inlay work in the Deccan there is nothing known to be so individually appealing as Bidri work with its vivid contrast of dull black and lustrous silver. Bidri once practiced in many parts of India, today exists only in Hyderabad in Andhra Pradesh and Bidar in Karnataka. But it is no exaggeration that the finest quality Bidriware is now produced in Hyderabad, while Bidar can lay claim to being the original home of this craft- Bidri is the adjectival form of Bidar. |  |

|

It is a 400 years-old craft. The origins of Bidriware are uncertain. The technique is believed to have originated from Persia where steel and copper objects were decorated with gold and silver inlay. The credit for developing this craft is the country is given to the Mughal rulers during whose reign the Persian crafts and craftsmen were introduced into India. The use of Zinc as a primary metal however, is peculiar to India. Over the last 180 years or so, a tradition has developed linking it with the Bahamani dynasty of the Deccan. |

| According to the story, the technique was introduced to the Bahmani kingdom from Iran (Via Iraq, Ajmer and Bijapur) and Alauddin Bahmani II took craftsmen from Bijapur where they were producing work of this sort and established them at Bidar, later the capital of the Bahmani kingdom. But even according to this account, when the Deccan was conquered by the Mughal emperor, north Indian officials set up permanent establishments and with political stability came patronage of the arts. The presence of Mughal and Rajput patrons and painters in the Deccan produced a revolution in Bijapuri taste, and with the fall of Bidar, Bijapur and Golconda, Mughal influence was all-pervasive. Thus the contribution of the Mughals to the present from of Bidriware is significant. |  |

| There are three main forms of bidriware according to the depth of embedding and the quality of the metal affixed to the surface. These are known as the nashan (deeply cut work) zar nashan (raised work) and tarkashi (wire inlay work). | |

| RAW MATERIAL The basic metal of this craft is an alloy of Zinc and Copper mixed in the proportion of 16:1. The melting temperature of this metal alloy is 800°F. Such an alloy is known as the 'white alloy' because the ratio of copper used is very little. Copper is mixed with zinc in the above stated proportion of 1:16 to provide the required base for being turned jet black when subjected to the ultimate oxidization process. |  |

| PROCESS The technical processes involved in the making of bidriware are complex and have different stages. The first stage is the sand casting stage. From ordinary soil matted with castor oil and resin, a mould is formed. After the mould is prepared, the molten metal alloy is poured into it. It is said that in olden days wax casting was used which has since been given up because of its arduous nature. | |

|

The second stage is filing. Since the surface of a newly cast piece is rough, it is made smooth with files and scrapers and sandpaper. Then a superficial layer of black is applied on the surface of the article by rubbing it with a solution of copper sulphate. This makes it easier for the artist to draw the design on it, which becomes visible on a black surface. |

| The third stage is that of designing. All the designs are drawn free hand. There are two types of inlay work-a) Wire work and b) sheet work. Floral designs mainly need silver sheet. In the sheet work again there are two sub-divisions - the Mehtabi design where the entire background is white and the design is black and the Aftabi where it is vice-versa (These names are Persian origin Mehtabi means Moon and the Aftabi means the Sun). The phooljali (flowering vine) design is the most popular and difficult to execute. The design is drawn with the help of a sharp metal stylus. |  |

|

The next stage is engraving. After the design is drawn it is entirely engraved by steel chisels designed by the artisans themselves and which are not available anywhere in the market. With the Bidri piece firmly fixed on a waxed stone or held in a vase, the craftsman engraves the design. |

| The fifth stage is the extremely intricate one of inlaying. Silver in the shape of wire or sheet is hammered into the grooves of the design. Then smooth filing is done with sandpaper or files or with the help of a buffing machine. After filing, the whole surface becomes white once again since the black colour is temporary and the silver work is hardly distinguishable. | |

| In the final stage, the article is subjected to a process of oxidation peculiar to the Bidri craft. For this, a particular kind of sand taken from the walls and ceilings of 200 to 300 year old mud buildings is mixed with sal ammoniac in the proportion 10:1 and the prepared paste is gently applied to the surface of articles to give a magical effect. The zinc and copper background turns black while the silver portion remains unaffected. Before the oxidization process, the articles are gently heated on an oven. Finally coconut oil or peanut oil or any vegetable oil is applied to the article to render the black portions bright and deep. |  |

| Only pure silver (99 per cent) should be used so that it is not tarnished in oxidization. When gold is inlaid it is known as Persian work for which there is not much demand - not only because of the high prices but also because gold inlaid Bidriware is not as elegant as its silver counterpart. PRODUCTION AND POTENTIAL The production of Bidriware in Hyderabad city is estimated to be around 75 to 80 lakhs, per annum, with a scope to increase the production by another 25%. | |

| Bidri products include a diverse range of objects including huqqa bases, bowls, boxes, candle stands, trays, ashtrays, vases, jewelry and buttons. The motifs vary from floral arabesques and intricately patterned leaves and flowers to geometric designs. |  |

|

Necessary marketing intelligence and scientific analysis of market trends and demand forecast could help stream line the production in such away that the shelf life of the product can minimized. Anees too highlighted the need for a market strategy to augment craft production. |

| Further reading: Development Commissioner (Handicrafts). Bidriware of Hyderabad. A Special Report. Warangal. | |

Bidri/Inlay on Metal of Karnataka,

Bidri is a unique metalware technique found only in India. It is a form of encrusted metalware, where one metal is inlaid on to another. The beauty of bidriware lies in the striking contrast of colours, with the glossy silver inlay being set off by the matt black metal. The craft of bidriwork is believed to have originated in Bidar (Karnataka). It has since spread to other places like Hyderabad (Andhra Pradesh). Bidri products include a diverse range of products including huqqa bases, bowls, boxes, candle stands, trays, ashtrays, vases, jewellery, and buttons. The motifs vary from floral arabesques and intricately patterned leaves and flowers to geometric designs. The technical processes involved in the making of bidriware are complex and include casting, designing engraving, inlaying, blackening, and polishing. All these processes can be performed either by a single artisan or else different processes can be undertaken by different artisans, including a moulder, a designer, an engraver, and an inlayer. The item is first cast with the help of a mould of red clay into which a molten solution --- predominantly copper and zinc with smaller amounts of lead and tin --- is poured. The engraving tool, a kalam or metal chisel of varied shapes and points is used to engrave the designs, which are drawn in free hand. For the inlay, metal wires --- usually silver, but occasionally gold or brass --- are laid in the engraved area. Besides being visually striking, bidriwork is also enduring; it does not rust and looks the same for years to come.

Bidri is a unique metalware technique found only in India. It is a form of encrusted metalware, where one metal is inlaid on to another. The beauty of bidriware lies in the striking contrast of colours, with the glossy silver inlay being set off by the matt black metal. The craft of bidriwork is believed to have originated in Bidar (Karnataka). It has since spread to other places like Hyderabad (Andhra Pradesh). Bidri products include a diverse range of products including huqqa bases, bowls, boxes, candle stands, trays, ashtrays, vases, jewellery, and buttons. The motifs vary from floral arabesques and intricately patterned leaves and flowers to geometric designs. The technical processes involved in the making of bidriware are complex and include casting, designing engraving, inlaying, blackening, and polishing. All these processes can be performed either by a single artisan or else different processes can be undertaken by different artisans, including a moulder, a designer, an engraver, and an inlayer. The item is first cast with the help of a mould of red clay into which a molten solution --- predominantly copper and zinc with smaller amounts of lead and tin --- is poured. The engraving tool, a kalam or metal chisel of varied shapes and points is used to engrave the designs, which are drawn in free hand. For the inlay, metal wires --- usually silver, but occasionally gold or brass --- are laid in the engraved area. Besides being visually striking, bidriwork is also enduring; it does not rust and looks the same for years to come.

|

Anees Ahmed S/o late Mr.Ghanil Ahmed learned the craft of bidri from his father. According to the artisan the craft has been in practice for over 400 years created at the time of the Bahmani Dynasty. Even though Anees is a graduate his interest in the craft tradition led him to make bidriware his career. This has not been an easy decision to make and keep in the face of diminishing markets. Earlier in his area more than 10 families participated in the craft but today only 2 families remain while others have moved to more gainful employment. |

| Bidri is a manually intensive craft. It is a time consuming, and requires concentration and patience. And yet Anees claims that the joy he gets from his work makes him pursue it passionately despite the hardships and limitations. | |

| Hyderabad boasts of one of the finest forms of creativity- the Bidri craft. Of all the beautiful gold and silver inlay work in the Deccan there is nothing known to be so individually appealing as Bidri work with its vivid contrast of dull black and lustrous silver. Bidri once practiced in many parts of India, today exists only in Hyderabad in Andhra Pradesh and Bidar in Karnataka. But it is no exaggeration that the finest quality Bidriware is now produced in Hyderabad, while Bidar can lay claim to being the original home of this craft- Bidri is the adjectival form of Bidar. |  |

|

It is a 400 years-old craft. The origins of Bidriware are uncertain. The technique is believed to have originated from Persia where steel and copper objects were decorated with gold and silver inlay. The credit for developing this craft is the country is given to the Mughal rulers during whose reign the Persian crafts and craftsmen were introduced into India. The use of Zinc as a primary metal however, is peculiar to India. Over the last 180 years or so, a tradition has developed linking it with the Bahamani dynasty of the Deccan. |

| According to the story, the technique was introduced to the Bahmani kingdom from Iran (Via Iraq, Ajmer and Bijapur) and Alauddin Bahmani II took craftsmen from Bijapur where they were producing work of this sort and established them at Bidar, later the capital of the Bahmani kingdom. But even according to this account, when the Deccan was conquered by the Mughal emperor, north Indian officials set up permanent establishments and with political stability came patronage of the arts. The presence of Mughal and Rajput patrons and painters in the Deccan produced a revolution in Bijapuri taste, and with the fall of Bidar, Bijapur and Golconda, Mughal influence was all-pervasive. Thus the contribution of the Mughals to the present from of Bidriware is significant. |  |

| There are three main forms of bidriware according to the depth of embedding and the quality of the metal affixed to the surface. These are known as the nashan (deeply cut work) zar nashan (raised work) and tarkashi (wire inlay work). | |

| RAW MATERIAL The basic metal of this craft is an alloy of Zinc and Copper mixed in the proportion of 16:1. The melting temperature of this metal alloy is 800°F. Such an alloy is known as the 'white alloy' because the ratio of copper used is very little. Copper is mixed with zinc in the above stated proportion of 1:16 to provide the required base for being turned jet black when subjected to the ultimate oxidization process. |  |

| PROCESS The technical processes involved in the making of bidriware are complex and have different stages. The first stage is the sand casting stage. From ordinary soil matted with castor oil and resin, a mould is formed. After the mould is prepared, the molten metal alloy is poured into it. It is said that in olden days wax casting was used which has since been given up because of its arduous nature. | |

|

The second stage is filing. Since the surface of a newly cast piece is rough, it is made smooth with files and scrapers and sandpaper. Then a superficial layer of black is applied on the surface of the article by rubbing it with a solution of copper sulphate. This makes it easier for the artist to draw the design on it, which becomes visible on a black surface. |

| The third stage is that of designing. All the designs are drawn free hand. There are two types of inlay work-a) Wire work and b) sheet work. Floral designs mainly need silver sheet. In the sheet work again there are two sub-divisions - the Mehtabi design where the entire background is white and the design is black and the Aftabi where it is vice-versa (These names are Persian origin Mehtabi means Moon and the Aftabi means the Sun). The phooljali (flowering vine) design is the most popular and difficult to execute. The design is drawn with the help of a sharp metal stylus. |  |

|

The next stage is engraving. After the design is drawn it is entirely engraved by steel chisels designed by the artisans themselves and which are not available anywhere in the market. With the Bidri piece firmly fixed on a waxed stone or held in a vase, the craftsman engraves the design. |

| The fifth stage is the extremely intricate one of inlaying. Silver in the shape of wire or sheet is hammered into the grooves of the design. Then smooth filing is done with sandpaper or files or with the help of a buffing machine. After filing, the whole surface becomes white once again since the black colour is temporary and the silver work is hardly distinguishable. | |

| In the final stage, the article is subjected to a process of oxidation peculiar to the Bidri craft. For this, a particular kind of sand taken from the walls and ceilings of 200 to 300 year old mud buildings is mixed with sal ammoniac in the proportion 10:1 and the prepared paste is gently applied to the surface of articles to give a magical effect. The zinc and copper background turns black while the silver portion remains unaffected. Before the oxidization process, the articles are gently heated on an oven. Finally coconut oil or peanut oil or any vegetable oil is applied to the article to render the black portions bright and deep. |  |

| Only pure silver (99 per cent) should be used so that it is not tarnished in oxidization. When gold is inlaid it is known as Persian work for which there is not much demand - not only because of the high prices but also because gold inlaid Bidriware is not as elegant as its silver counterpart. PRODUCTION AND POTENTIAL The production of Bidriware in Hyderabad city is estimated to be around 75 to 80 lakhs, per annum, with a scope to increase the production by another 25%. | |

| Bidri products include a diverse range of objects including huqqa bases, bowls, boxes, candle stands, trays, ashtrays, vases, jewelry and buttons. The motifs vary from floral arabesques and intricately patterned leaves and flowers to geometric designs. |  |

|

Necessary marketing intelligence and scientific analysis of market trends and demand forecast could help stream line the production in such away that the shelf life of the product can minimized. Anees too highlighted the need for a market strategy to augment craft production. |

| Further reading: Development Commissioner (Handicrafts). Bidriware of Hyderabad. A Special Report. Warangal. | |

Black Pottery of Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh,

Nizamabad ,about 100km north of Varanasi, is a small town situated on the river Tons which feeds several lakes on the outskirts of the town. The entire districts of Azamgarh and Mau in Uttar Pradesh are the geographical areas of Nizamabad Black Pottery. In 18th century, Azamgarh was included in the sirkars of Jaunpur district and Ghazipur in the subah of Allahabad. It was ruled by Mohhabat Khan, popularly known as the Raja of Azamgarh. Azamgarh is rich in cultural and religious activities as the district lies in the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh. Its most famous craft is its distinctive black clay pottery. Traditional black clay products include religious figures of gods and goddesses, decorative items and utensils. At Nizamad in Azamgarh district a specialised lustrous black pottery is made. It is rubbed with a special oil and then double fired. Floral and geometric designs are etched on the surface. The block surface with its silvery design has an uncanny resemblance to the bidri metal ware, the matt black of the base offset by the silver sheen of the designs. The deep, black colour is obtained by mixing the local clay with mustard oilseed cake. The silvery ornamentation on the pottery is done by rubbing an amalgam of mercury and tin into the etched and baked patterns on the pots, thereby producing the silvery tracery. The products made include vases, cups and saucers, water jugs, surahis, plates, jars, and flower pots.

Nizamabad ,about 100km north of Varanasi, is a small town situated on the river Tons which feeds several lakes on the outskirts of the town. The entire districts of Azamgarh and Mau in Uttar Pradesh are the geographical areas of Nizamabad Black Pottery. In 18th century, Azamgarh was included in the sirkars of Jaunpur district and Ghazipur in the subah of Allahabad. It was ruled by Mohhabat Khan, popularly known as the Raja of Azamgarh. Azamgarh is rich in cultural and religious activities as the district lies in the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh. Its most famous craft is its distinctive black clay pottery. Traditional black clay products include religious figures of gods and goddesses, decorative items and utensils. At Nizamad in Azamgarh district a specialised lustrous black pottery is made. It is rubbed with a special oil and then double fired. Floral and geometric designs are etched on the surface. The block surface with its silvery design has an uncanny resemblance to the bidri metal ware, the matt black of the base offset by the silver sheen of the designs. The deep, black colour is obtained by mixing the local clay with mustard oilseed cake. The silvery ornamentation on the pottery is done by rubbing an amalgam of mercury and tin into the etched and baked patterns on the pots, thereby producing the silvery tracery. The products made include vases, cups and saucers, water jugs, surahis, plates, jars, and flower pots.

Black Smithing – Garzo,

Bhutan has a strong tradition of working with iron to manufacture iron goods such as farm tools, knives, swords and utensils. Each district has an ironsmith who manufactures and repairs goods for local use. Today, many tools and hardware are coming from India. PRACTITIONERS Every district will have a black smith. Wochu, in Paro District has a lot of ironwork as has Khaling. PRODUCTS Knives, swords, spades, sickles, axes, shoes for horses, horse bridles, stirrups, agricultural tools, metal tips for arrows, ploughs. Metal Torch Made of iron, it was used during warfare. It serves a dual purpose: as a torch to hold fire; the water at the bottom of the receptacle prevented the metal from heating. And if the need arose, when swung around, the water would extinguish the fire, allowing the torch to be used as a weapon of self-defence.

Bhutan has a strong tradition of working with iron to manufacture iron goods such as farm tools, knives, swords and utensils. Each district has an ironsmith who manufactures and repairs goods for local use. Today, many tools and hardware are coming from India. PRACTITIONERS Every district will have a black smith. Wochu, in Paro District has a lot of ironwork as has Khaling. PRODUCTS Knives, swords, spades, sickles, axes, shoes for horses, horse bridles, stirrups, agricultural tools, metal tips for arrows, ploughs. Metal Torch Made of iron, it was used during warfare. It serves a dual purpose: as a torch to hold fire; the water at the bottom of the receptacle prevented the metal from heating. And if the need arose, when swung around, the water would extinguish the fire, allowing the torch to be used as a weapon of self-defence.

Black Writing Ink,

Evidence based on ancient manuscripts of paper and tad-patra, written with a long lasting and hard wearing indigenously produced black ink, indicates this ink to have been in use for at least a thousand years. The writing in the Dasa Bhumiswara Mahayana Sutras (6th century) and the Astasahasrika Pragyaparamita (10th century) stands testimony to this. This black writing ink was used in most government offices in Nepal - for official documents and accounts - till the coming of democracy in the state when imported papers and inks came to be widely used since this indigenous ink could not be used for filling fountain pens. However, traditionalists, astrologers, and artists, among others, continue to use the traditional black ink that is still made in Lalitpur. This ink was used for writing and illustrations on harital paper and on the ivory lokta bark paper.

Evidence based on ancient manuscripts of paper and tad-patra, written with a long lasting and hard wearing indigenously produced black ink, indicates this ink to have been in use for at least a thousand years. The writing in the Dasa Bhumiswara Mahayana Sutras (6th century) and the Astasahasrika Pragyaparamita (10th century) stands testimony to this. This black writing ink was used in most government offices in Nepal - for official documents and accounts - till the coming of democracy in the state when imported papers and inks came to be widely used since this indigenous ink could not be used for filling fountain pens. However, traditionalists, astrologers, and artists, among others, continue to use the traditional black ink that is still made in Lalitpur. This ink was used for writing and illustrations on harital paper and on the ivory lokta bark paper.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

Modern writing inks contain gallic acid, tannic acid, and ferrous sulphate. Some aniline dyes are added for temporary colouring. The traditional Nepalese ink is an emulsion of colours. So shellac and other ingredients form a heterogeneous mixture; possibly, the resin and the soot do not have any chemical reaction.

One of the chief ingredients of the black ink is lamp black or soot. If only a small quantity of ink is required it is prepared by lighting an oil based earthen lamp (maka dalu). A cotton wick soaked in mustard oil is placed in the lamp base and its wick end is lit. Simultaneously a small clay-bowl is inverted over the lamp base. As the lamp burns the soot is deposited on the inside of the upturned clay bowl.

If a larger quantity of ink is required a small oven is lit using a resinous pine wood (diyalo) - found in the Himalayan regions - which burns with a luminous flame. A clay bowl (bhigut) is inverted over the oven - as the firing progresses, the bhigut gets covered with soot on the inside. When this inverted bowl gets heated it is replaced. Often, a copper vessel (phosi) is used instead of the clay bowl.

To prepare the black ink a proportion of water is added to a mixture of soot and hirakasi (iron sulphate). The mixture is then sieved through a fine cloth. The product is the black writing ink. Borax, imported from Tibet was earlier used for giving gloss to the letters written in ink.

The soot collected by burning the diyalo wood consists of carbon in its purest form. The soot does not dissolve in water, but when mixed vigorously, it forms a very fine emulsion with the ferrous sulphate solution and results in a deep black colour of great permanence.

Laha - a variety of black ink - is prepared by combining powdered raw lac or shellac to water and boiling the mixture. The lac melts in the boiling water and the solution becomes brownish. The boiling is continued till the volume is reduced to a quarter. Next, a small quantity of this mixture is put into a black stone mortar (gaji khal) and a small quantity of black soot is added. The mixture is ground and more and more soot is added during the grinding until the required consistency is reached. Then borax or glue is added and mixed in - this provides lustre and gloss to the ink. The ink is then stored in clay containers till required. The writing in this ink is done with the traditional bamboo pen called sir kalam.

Block Making in Wood for Hand Printing of Andhra Pradesh/Telangana,

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Block Making in Wood for Hand Printing of Delhi,

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Block Making in Wood for Hand Printing of Rajasthan,

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Block Making in Wood for Hand Printing of Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh,

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Block Making in Wood for Hand Printing of Uttar Pradesh,

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Hand-block printing on textiles is practised all over India, with each region having evolved its own technique(s), style(s), design patterns, and distinctive colours. The one aspect that remains constant, however, is the use of hand-blocks for printing. Pethapur in Gujarat has long been an important centre for hand-block making. In Rajasthan the main centre is in Jaipur and the designs are carved on sagon wood. These block-makers are hereditary craftspersons who trace their descent from the Shia Muslims of Persia who settled here many centuries ago. Pilakhuwa in Uttar Pradesh is another important centre for block-making. Here the block- makers specialise in making brass blocks that are used for outline printing. Unfortunately due to the rising demand for mill-printed fabrics many traditional block-makers are having to find alternative uses for their carving skills. One of the areas into which they are expanding is the making of boxes and other wood products that are intricately carved and inlaid with metal.

Block Making of Pethapur, Gujarat,

Handblock printing is one of the most oldest form of creating design on fabrics manually. The art of block printing and making is heavily recognised as a lot of effort goes in these processes. Traditional block making has been followed as a practice by the natives of Pethapur village in Gandhinagar, Gujarat since ages. It is situated 40 kms away from Ahmedabad, which is the biggest hub of market and sale. It is the only enduring centre of woodblock production and carving in India. The block makers of Pethapur believe that many enturies ago, women got frustated by wearing the plain white clothes and such a printing device was made with bangles that could colour the cloth and print patterns.

Handblock printing is one of the most oldest form of creating design on fabrics manually. The art of block printing and making is heavily recognised as a lot of effort goes in these processes. Traditional block making has been followed as a practice by the natives of Pethapur village in Gandhinagar, Gujarat since ages. It is situated 40 kms away from Ahmedabad, which is the biggest hub of market and sale. It is the only enduring centre of woodblock production and carving in India. The block makers of Pethapur believe that many enturies ago, women got frustated by wearing the plain white clothes and such a printing device was made with bangles that could colour the cloth and print patterns.

Blue Pottery of Jaipur, Rajasthan,

Jaipur is well known for its blue art pottery. This craft had its beginning in the first part of the 19th century. Blue pottery came to India from Persia and Afghanistan, but the Jaipur craftspersons learnt the art from the Delhi and Multan potters. After the Mughal era, there was a temporary lull till the craft was revived by master craftsman Kirpal Singh Shekhawat. The base for this pottery is quartz and not clay. All the materials that are used --- quartz, raw glaze, sodium sulphate, and fuller's earth or multani mitti --- require the same temperature, and the pottery needs to be fired only once. The slip does not develop any cracks, and the pottery is impervious, hygienic, and suitable for daily use. The neck and the lip are shaped on the wheel. For the decorative work, the pot is rotated and the ornamentation is done with a brush made of squirrel hair. The turquoise or blue colour is obtained by mixing crude copper oxide from old scrap baked in a kiln, with salt or sugar, and then filtering it for use. The dark ultramarine colour is got from cobalt oxide. Some of the pottery is semi-transparent and it is decorated with arabesque patterns, interspersed with animal and bird motifs. The other shades found in the pottery are pink, yellow, green, brown, mauve, gray, and black. The products made include plates, flower vases, soap dishes, surahis (small pitcher), trays, coasters, fruit bowls, door knobs, and glazed tiles with hand painted floral designs. The craft is found mainly in Jaipur, but also in Sanganer, Mahalan, and Neota.

Jaipur is well known for its blue art pottery. This craft had its beginning in the first part of the 19th century. Blue pottery came to India from Persia and Afghanistan, but the Jaipur craftspersons learnt the art from the Delhi and Multan potters. After the Mughal era, there was a temporary lull till the craft was revived by master craftsman Kirpal Singh Shekhawat. The base for this pottery is quartz and not clay. All the materials that are used --- quartz, raw glaze, sodium sulphate, and fuller's earth or multani mitti --- require the same temperature, and the pottery needs to be fired only once. The slip does not develop any cracks, and the pottery is impervious, hygienic, and suitable for daily use. The neck and the lip are shaped on the wheel. For the decorative work, the pot is rotated and the ornamentation is done with a brush made of squirrel hair. The turquoise or blue colour is obtained by mixing crude copper oxide from old scrap baked in a kiln, with salt or sugar, and then filtering it for use. The dark ultramarine colour is got from cobalt oxide. Some of the pottery is semi-transparent and it is decorated with arabesque patterns, interspersed with animal and bird motifs. The other shades found in the pottery are pink, yellow, green, brown, mauve, gray, and black. The products made include plates, flower vases, soap dishes, surahis (small pitcher), trays, coasters, fruit bowls, door knobs, and glazed tiles with hand painted floral designs. The craft is found mainly in Jaipur, but also in Sanganer, Mahalan, and Neota.