Bandhej and Leheriya/Cloth Tie-Resist-Dyeing of Odisha,

The tie-and-dye technique practised at Rajasthan is both similar and different to the technique practised in Gujarat. At both centres it is the fabric that is tied and dyed to the design's chosen pattern. A large number of colours are used because once the base colour is tied in, a lot of colours can be applied on to the fabric at different stages and then tied and removed progressively. The motifs that are used are flowers, leaves, creepers, animals, birds, and human figures in dance poses; geometrical patterns are also common. The designs are given names like mountain design, kite design, and dol design. The dyeing is done in matching or contrasting colours. Dots are used to make up the designs. Do-rookha dyeing or different colours on either side is also practised by the craftsmen here. The lehariya technique has long lines or bands in various colours found all over the body of the sari or cloth. The lehariya cloths have their own names depending on the designs: pancharangi (five-coloured) and satrangi (seven-coloured) are common. Bandhanis are linked to various seasons, festivals and rituals for which there are specific designs and colours.

The tie-and-dye technique practised at Rajasthan is both similar and different to the technique practised in Gujarat. At both centres it is the fabric that is tied and dyed to the design's chosen pattern. A large number of colours are used because once the base colour is tied in, a lot of colours can be applied on to the fabric at different stages and then tied and removed progressively. The motifs that are used are flowers, leaves, creepers, animals, birds, and human figures in dance poses; geometrical patterns are also common. The designs are given names like mountain design, kite design, and dol design. The dyeing is done in matching or contrasting colours. Dots are used to make up the designs. Do-rookha dyeing or different colours on either side is also practised by the craftsmen here. The lehariya technique has long lines or bands in various colours found all over the body of the sari or cloth. The lehariya cloths have their own names depending on the designs: pancharangi (five-coloured) and satrangi (seven-coloured) are common. Bandhanis are linked to various seasons, festivals and rituals for which there are specific designs and colours.

Bandhej-Tie-Resist-Dyeing of Gujarat,

Bandhej is the art of the tie and dye in Gujarat. Traditionally, each village had its own typical colour schemes and designs, depending on the religious and social customs of the place. The centres where the craft was practised include Jamnagar, Anjar, and Bhuj. This craft now faces severe competition from the machine printing of bandhej designs. Bandhej requires the cloth to be dipped into a colour-bath of choice, after which the cloth is folded to a quarter of its size. The area to be worked upon --- a sari border, pallu, or the body of the sari --- is separated, and then is tied with strings to form various designs. The designs are made from a combination of small dots and circles. The artisans makes the designs without the help of coloured strings or blocks. The tying of the border and the discharge of the colour is called sevo bandhavo. The borders are broad, and are worked both in complementary and contrasting colours. The designs are composed with minute attention to detail. An inexhaustible number of colour schemes are used. The colouring technique involves the lightest shade being worked in first, after which this is tied and a darker colour is inserted. This is done till the darkest shade is reached. The last colour the cloth is dipped into is the colour used as the background. The colours used commonly include red, black, golden yellow, and maroon. The quality of the bandhej can be determined by the size of the dots: the smaller and closer to the size of a pinhead the dots are, the finer is the quality of the bandhej.

Bandhej is the art of the tie and dye in Gujarat. Traditionally, each village had its own typical colour schemes and designs, depending on the religious and social customs of the place. The centres where the craft was practised include Jamnagar, Anjar, and Bhuj. This craft now faces severe competition from the machine printing of bandhej designs. Bandhej requires the cloth to be dipped into a colour-bath of choice, after which the cloth is folded to a quarter of its size. The area to be worked upon --- a sari border, pallu, or the body of the sari --- is separated, and then is tied with strings to form various designs. The designs are made from a combination of small dots and circles. The artisans makes the designs without the help of coloured strings or blocks. The tying of the border and the discharge of the colour is called sevo bandhavo. The borders are broad, and are worked both in complementary and contrasting colours. The designs are composed with minute attention to detail. An inexhaustible number of colour schemes are used. The colouring technique involves the lightest shade being worked in first, after which this is tied and a darker colour is inserted. This is done till the darkest shade is reached. The last colour the cloth is dipped into is the colour used as the background. The colours used commonly include red, black, golden yellow, and maroon. The quality of the bandhej can be determined by the size of the dots: the smaller and closer to the size of a pinhead the dots are, the finer is the quality of the bandhej.

Banjara Tribal Embroidery and Mirror Work of Maharashtra,

This craft is practised by the Banjara or nomadic tribal women also known as the Lambadis. The clothes are expressive of their exuberance, the entire ensemble being pieced together using gaily coloured fabrics, embellished with mirrors, glass beads, and cowrie shells. This craft is characterised by vibrant colours, fascinating combinations and exquisite embroidery. Products which showcase Banjara needle craft include bags, belts, batwas or purses, yokes, borders, salwar kameez suits, skirts, blouses, pillows, cushions, quilts, and bedspreads. Drawing upon the traditions of the past, the embroidery of Banjara tribal women evokes a scintillating flight of fancy.

This craft is practised by the Banjara or nomadic tribal women also known as the Lambadis. The clothes are expressive of their exuberance, the entire ensemble being pieced together using gaily coloured fabrics, embellished with mirrors, glass beads, and cowrie shells. This craft is characterised by vibrant colours, fascinating combinations and exquisite embroidery. Products which showcase Banjara needle craft include bags, belts, batwas or purses, yokes, borders, salwar kameez suits, skirts, blouses, pillows, cushions, quilts, and bedspreads. Drawing upon the traditions of the past, the embroidery of Banjara tribal women evokes a scintillating flight of fancy.

Bas-Relief House Decorations in the Terai,

For generations, women across the terai in the hot fertile plains of southern Nepal, have transformed the verandahs and outer walls of their homes into colourful designs dedicated to the Hindu goddess Laxmi who brings good fortune and a rich harvest. The most lavishly decorated painted houses are found in the eastern terai, in the districts of Morang, Sunsari, Udaypur, Dhanusa, Saptari, and Jhapa. Different subgroups of Tharu, as well as Maithili, Satar, and Rajbanshi also have on a tradition of painted houses.

For generations, women across the terai in the hot fertile plains of southern Nepal, have transformed the verandahs and outer walls of their homes into colourful designs dedicated to the Hindu goddess Laxmi who brings good fortune and a rich harvest. The most lavishly decorated painted houses are found in the eastern terai, in the districts of Morang, Sunsari, Udaypur, Dhanusa, Saptari, and Jhapa. Different subgroups of Tharu, as well as Maithili, Satar, and Rajbanshi also have on a tradition of painted houses.

PRACTITIONERS

The painting and the bas-relief is an art practised almost exclusively by the woman of the household. In the terai, where there are no professional artists, no art schools, it is the women who preserve traditions. The young girls observe their mothers mixing clay with dung, milk with coloured powders. They watch them develop the designs and learn to re-do them each year at festival time. The art is passed on from mother to daughter through a strong oral tradition.

DETAILS

The outdoor 'canvas' on the walls is a mixture of clay, straw, and dung. Symbols from the Hindu epics, as well animal and bird motifs, are popular throughout. Style and pattern, however, vary from region to region in the terai.

The Kochila Tharu, living mostly in Morang and Sunsari, apply decorative designs to their verandah walls and balconies. The vivid patterns are particularly elaborate around windows, doors, and small openings including chicken house doors. Many Kochila Tharu walls depict vines and flowers, in particular the lotus flower, the nine-petalled symbol of perfection.

Scattered throughout the easternmost districts of Jhapa and Morang, the Satar and Rajbanshi, while small in number, leave their mark with a strong house painting tradition of their own. Most Satars and Rajbanshis live in small one-storey houses with verandahs sheltered from the burning sun by low thatched eaves. Their modest homes are as clean and carefully ornamented as those of their wealthier terai neighbours. Satar women seem to favour large-scale animals and abstract designs, which often fill up the entire seven-foot high walls of their houses. In a surprisingly contemporary style, Rajbanshi women shape and paint designs taken from the world around them, such as stylised animals or even the symbols of a deck of cards: hearts, clubs, spades, and diamonds.

The Maithili women are the best known artists outside the terai. Located in the Janakpur region, they have developed a style quite similar to that of their Maithili sisters across the Indian border in Bihar. They seldom create bas-reliefs, but draw free and imaginative designs, often using religious themes including Hindu figures, popular stories, and mythological beings.

Far to the west, along the Karnali river, the Kathariya Tharu, one of the smallest subgroups of Tharu shape and paint distinctive large scale geometric patterns in bas-relief using muted and natural colours. The same patterns are repeated inside the house, painted on room dividers and sculpted onto large rice containers.

Many Dangaura Tharu, believed by many to be the earliest Tharu of the west, carried the memory of their traditional long house with them when they left Dang Valley in search of better lives and greener pastures. Their long houses can be found in Surkhet, Bardiya, Kailali, and Kanchanpur districts as well as Dang, adorned with simple unpainted clay bas-reliefs of peacocks, snakes, and elephants to represent good fortune, a plentiful harvest, or fertility.

The terai is region of ethnic and religious diversity. Living in the same villages alongside Hindus and animists, Muslim women celebrate life by designing and patterning abstract designs on their houses; green and purple are the predominant colours, and sparkling mirror fragments are also used.

DESIGNS

Among the more popular designs is the peacock; this bird - with its associations with happiness, passion, and bliss - decorates more painted houses than any other bird. Another great favourite is the green parrot, considered a symbol of love and a popular subject for wedding paintings. The elephant symbolises strength, virility, gentleness, and calm and it is often painted on Maithili houses. Dangaura Tharu women in the west also portray elephants on the walls of their houses in the form of clay bas-reliefs.

Information and photographs based on research conducted by Pamela Deuel Meyer and Kurt W. Meyer, Los Angeles, California.

Basholi Miniature Painting of Jammu,

Basholi paintings are miniature paintings linked with the town of Basholi in the foothills of the Shivalik mountains in Kathua district. This was once a small kingdom ruled by Chanderwanshi rajputs. Raja Sangrampal, who ruled this kingdom from 1635 to 1673 is said to have been interested in miniature paintings, owing to his friendship with the Mughal prince, Dara Shikoh. However, it was during the regime of his grandson, Raja Kripal Singh, that miniature painting actually flourished. In the late 17th century, Basholi emerged as a great centre of painting. The different themes included religious, secular, historical, literary, and contemporary motifs. The paintings are also adept at depicting emotions, contextualised in the lyrical setting of sense of the Basholi landscape.

Basholi paintings are miniature paintings linked with the town of Basholi in the foothills of the Shivalik mountains in Kathua district. This was once a small kingdom ruled by Chanderwanshi rajputs. Raja Sangrampal, who ruled this kingdom from 1635 to 1673 is said to have been interested in miniature paintings, owing to his friendship with the Mughal prince, Dara Shikoh. However, it was during the regime of his grandson, Raja Kripal Singh, that miniature painting actually flourished. In the late 17th century, Basholi emerged as a great centre of painting. The different themes included religious, secular, historical, literary, and contemporary motifs. The paintings are also adept at depicting emotions, contextualised in the lyrical setting of sense of the Basholi landscape.

Basketry of Ladakh,

Basket weaving is a popular craft in practiced Ladakh for producing baskets made out of chipkiang grass commonly found all over Ladakh. This variety of grass is used to weave baskets which are then used for carrying household items and daily chores. Production clusters center around Kargil, Bod Kharbu, Lamayuru, Saspol, Nimmo, Chushot. The baskets produced are called tsepo which are essentially backpack baskets.

Basket weaving is a popular craft in practiced Ladakh for producing baskets made out of chipkiang grass commonly found all over Ladakh. This variety of grass is used to weave baskets which are then used for carrying household items and daily chores. Production clusters center around Kargil, Bod Kharbu, Lamayuru, Saspol, Nimmo, Chushot. The baskets produced are called tsepo which are essentially backpack baskets.

Batik Craft of Sri Lanka,

Batik is a variety of fabric decoration that has long been in existence in Sri Lanka; however its potential has been explored adequately only in the past two decades. The term 'batik' is derived from 'tik', which signifies drawing, painting, and colouring; in this craft, coloured designs are made on the fabric using varied techniques. A factor that is instrumental in the continuity of batik traditions is that the craft can be practised with minimal resources. Most of the artisans involved in the batik craft are women. Artistic and well-made quality batiks are in high demand by both the locals and the tourists. The craft provides ample opportunities of employment and is a steady source of foreign exchange for the country.

Batik is a variety of fabric decoration that has long been in existence in Sri Lanka; however its potential has been explored adequately only in the past two decades. The term 'batik' is derived from 'tik', which signifies drawing, painting, and colouring; in this craft, coloured designs are made on the fabric using varied techniques. A factor that is instrumental in the continuity of batik traditions is that the craft can be practised with minimal resources. Most of the artisans involved in the batik craft are women. Artistic and well-made quality batiks are in high demand by both the locals and the tourists. The craft provides ample opportunities of employment and is a steady source of foreign exchange for the country.

Batik on Fabric of Nepal,

Batik - the process of printing coloured designs and patterns on textiles by resisting with wax those parts that are not meant to be dyed - is a relatively new craft in Nepal; it is now widely practised to cater to the tourist and export markets.

Batik - the process of printing coloured designs and patterns on textiles by resisting with wax those parts that are not meant to be dyed - is a relatively new craft in Nepal; it is now widely practised to cater to the tourist and export markets.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

A piece of white cloth is stretched on a rectangular wooden frame. After the artist has sketched out the design on the cloth with a pencil or with charcoal, the colour combination is decided on. If their are four or five colours in the design, the first consideration is the sequence in which the colours are to be dyed, with the lighter colours being dyed first (like yellow and green), followed by darker colours like blues and reds, with black normally being the last colour.

The wax, in a metal vessel, is placed on a burner and melted; it is usually applied with a brush. As the base white colour cannot be replicated, it is the first colour that is resisted with an application of wax in those parts that are earmarked as white in the pattern determined upon. This is followed with the fabric being dyed in the colour that has been sequenced next. Once the fabric is dry, those parts that are meant to retain that particular colour are then resisted with wax. It is in this manner that the fabric is dyed - the parts meant to retain the colour are resisted with wax and this sequence is continued until the final black colour.

The final operation is the removal of the wax from the batik cloth. This can be done either by covering the batik with a piece of paper and applying a hot iron over it or by boiling the batik cloth in water till the wax melts off. The process is time-consuming but the result is beautiful.

PRODUCT RANGE

Batik pieces are being used not only for wall hangings but have a range of other creative uses, including being used in cards, linen, and lamp shades.

Batik on Leather of Shanti Niketan, West Bengal,

Shanti Niketan pioneered the craft of making modern decorative leather items as well as utility articles. From foot wear to bags to utilitarian items and decorative pieces the items have patterns and designs that range from the sophisticated to basic. Available in myriad colors the craftspeople are willing to experiment with new patterns and products.

Shanti Niketan pioneered the craft of making modern decorative leather items as well as utility articles. From foot wear to bags to utilitarian items and decorative pieces the items have patterns and designs that range from the sophisticated to basic. Available in myriad colors the craftspeople are willing to experiment with new patterns and products.

Batik on Textiles and Leather of Bangladesh,

This relatively new craft technique has provided the artisans with fresh avenues to explore their creativity. Using wax as a resist new designs and patterns are emerging on both textiles (cotton and silk) and on leather.

This relatively new craft technique has provided the artisans with fresh avenues to explore their creativity. Using wax as a resist new designs and patterns are emerging on both textiles (cotton and silk) and on leather.

Batik on Weaving of Andhra Pradesh/Telangana,

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

Batik on Weaving of Pondicherry,

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

Batik on Weaving of Uttarakhand,

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

Batik/Wax-Resist Dyeing on Cloth of Gujarat,

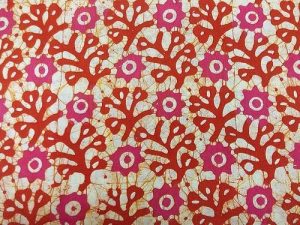

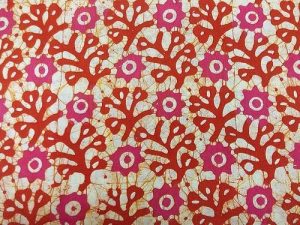

Mundra, Anjar, Valsad, and Bhuj are the main production centres of this craft. In the18th and 19th centuries the East India Company used to export batik print products. Today its production depends on indigenous demand rather than on the export market. In this process a carved wooden block is immersed in melted paraffin wax and printed on white cloth. The cloth is then dipped in lighter colours followed by an application of wax. The wax retains the colour of the cloth wherever required. The natural hair-like cracks, permeated by various colours have a unique appeal, an effect, which is impossible to achieve in any other kind of printing. The design repertoire includes floraand fauna and geometric designs.

Mundra, Anjar, Valsad, and Bhuj are the main production centres of this craft. In the18th and 19th centuries the East India Company used to export batik print products. Today its production depends on indigenous demand rather than on the export market. In this process a carved wooden block is immersed in melted paraffin wax and printed on white cloth. The cloth is then dipped in lighter colours followed by an application of wax. The wax retains the colour of the cloth wherever required. The natural hair-like cracks, permeated by various colours have a unique appeal, an effect, which is impossible to achieve in any other kind of printing. The design repertoire includes floraand fauna and geometric designs.

Batik/Wax-Resist Dyeing on Cloth of Karnataka,

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

Batik/Wax-Resist Dyeing on Cloth of Kerala,

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

Batik/Wax-Resist Dyeing on Cloth of Madhya Pradesh,

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.