The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

The process of batik allows the imagination of the printer to come into play. Wax is used as a resist on those parts of the fabric which will be dyed a shade different from the base colour. The base is dyed a dark colour and the fabric is washed in boiling water and soap after all the colours have been absorbed. The wax is then removed and the dye seeps through the cracks in the irregular network of the breaking wax-coat. Thus, a spontaneous and unique design, variegated in hue, is formed, giving the fabric an unusual appearance.

Baul singers are a sect of minstrels living in the rural areas of West Bengal and Bangladesh. They believe in achieving spiritual liberation through their music and poetry. Bauls keep on travelling from place to place to earn a living through their oral tradition and refuse the conventional ideology of life. Their music is about love, longing for mystic union with the divine or man’s relationship with god and reflects the influence of the Hindu Bhakti movement and Sufism of Islam. They wear very simple cotton clothes and are accompanied with their instruments like ektara (single stringed instrument), dotara (two to five-stringed instrument) or duggi (a drum with a kettle drum shape). The exact origin of the Bauls are not known, but it is derived from a Sanskrit words ‘vatula’ (eccentric, crazy) or from ‘vyakula’ (impatiently eager), which can be clearly seen in their carefree lifestyle. In 2005, Baul tradition was included in UNESCO’s list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Gujarat is the land of embellishments where the arid landscape is brought to life with the colourful bead accessories. Natural elements like clay, cowrie shells and ivory have given the bead craft an edge over metal and artificial jewellery. The beadwork from Gujarat comes in household items, women's jewellery and other adornments.

The town of Purdilnagar in Uttar Pradesh is famous for its glass bead making activity. The craft is spread across 100km in and around the twon and the surrounding villages. Purdilnagar is the hub for sourcing the raw material.The crafting of the bead is done using two different kind of methods. The first is called Torching and the second is known as Furnace method. The former is primarily carried out by females. The practitioners of Purdilnagar are highly dependent on this craft for their source of income. Simultaneously flourishing activities in the region are mould making for the beads and washing as well as acid cleaning for the beads.

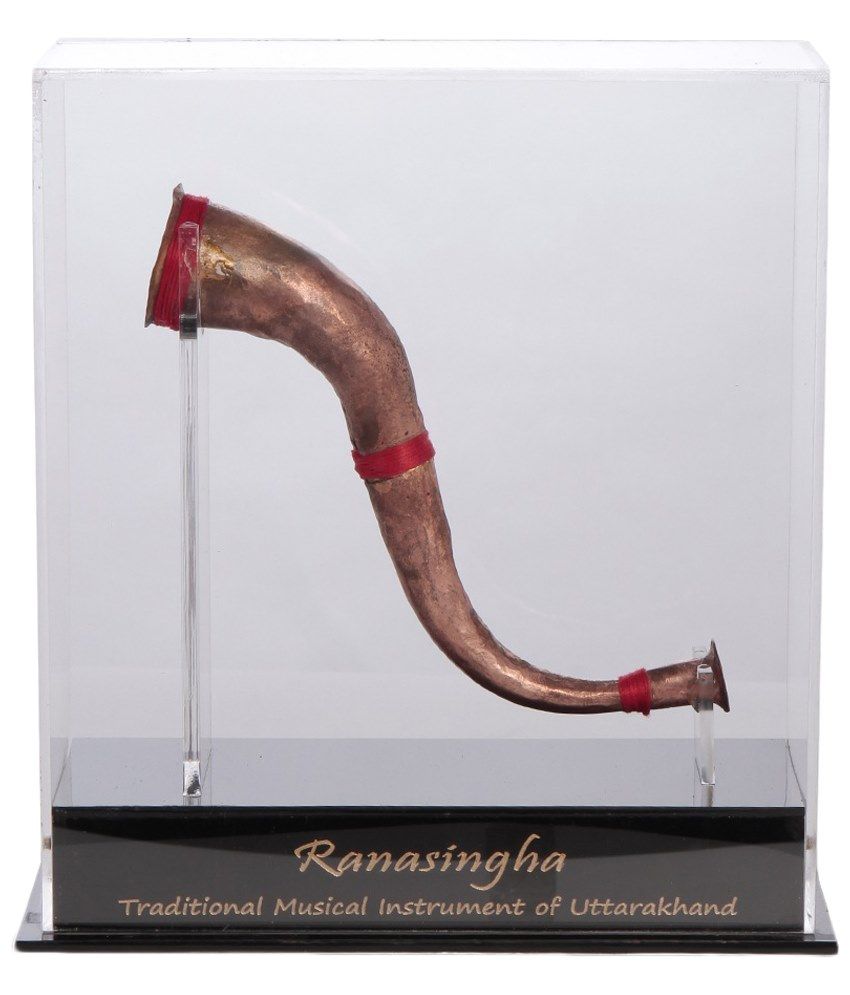

Both Kumaon and Garwhal have an ancient cottage industry of fashioning copper into beaten wares. Copper mining was a thriving industry in the Kumaon and Garhwal hills till around the first half of the 1800s. The mountains were once rich in copper ore that was extracted over thirty sites well into the 19th century. The miners or agari, dug narrow passages into the mountains through the layers of mud, clay, sand, and rock. they smelted ore into copper and sold it in the village coppersmith called Tamta. The Tamta community got its name because of their working with copper or Tamba. BHANGURI AND RANSINGHA The two main horns, the curving Ransingha and the long-horned Bhanguri are made of detachable parts. the horns are constructed to their length, the sheet is also cut to their shape and the joints are brazed. the large Bhanguri is played with its flared head inclined to the ground. the small Bhanguri makes a conch-like sound while the bigger makes a variety of sounds depending on the player.

The craft of beaten silver work started in Bhabanipur, West Bengal during the colonial days. The cluster would cater to the demands for intricate and exotic silverware of the kings of different states, dignitaries like viceroys and the governors. However, after independence and the abolition of the Zamindari system, the glory of the craft started fading away due to lack of clientele. Craftsperson's started diversifying their skills in an attempt to expand their production to other metal works and also to making trophies, medallions and other minor utensils.

Silver sheets are beaten into desired shapes on an anvil, and the ends fused with paan, a solution of silver and brass in the ratio of 16:7. Designs are chiselled on the surface, and the polishing is done by hand.

Begumpur is a town in Hooghly district of West Bengal. The weavers in Begumpur weave light-weight cotton saris in bright solid colours. Along with saris they also weave cotton dhotis. Earlier, weavers in Begumpur weaved saris using Mathapar technique which had a plain border without any ornamentation. Since mathapar sarees were not in high demand, their production gradually faded. Begumpur weavers started experimenting to revive their local industry. They introduced extra- weft in designs and unique colour combinations. In addition, they started using pit looms and frame looms, which helped increase their capacity of production. Today, Begampur sarees are identified by their contrasting borders which often have figured motifs.

Bell Metal Casting of Tamil Nadu Kumbakonam and Nachiarkoil in Tanjore district of Tamil Nadu, is well known for the practice of Temple Bell craft. The craft is traditionally practiced by migrant gold and silver smiths from Ngercoil in Kanniyakumari district in the 19th century. The settled in the area after having discovered that vandal, the light brown sand on the banks of the river Kaveri, was perfect for box mould casting. The beauty of the practice is that no modern machines and furnaces are used; rather smelting and casting are done by primitive methods. The art has been passed on from generation to generation. The craft is extensively used to produce large temple bells, hand-held bells for worship at homes, water pots and tumblers used for rituals. For the craft, the most important aspect is making of proper alloy consisting of copper and tin to get the correct sound. The ratio for the proper alloy is 80 is to 20 of copper is to tin.

Bell-metal ware - dominantly cooking ware, now supplemented with some decorative items - made in Odisha is the preserve of the kansari community, experts at this particular craft. Bishnu Sara Sahu, a mastercraftsman, describes the making of bell-metal cooking ware as a traditional craft, passed down through generations, focused within a particular set of villages in Odisha, with Chandanpur and Baghi being two of the well-known ones in the area. The reason for traditionally making cooking ware and kitchenware from the bell-metal alloy is thatthis alloy has several medicinal properties, which the food or water kept in them acquires. These medicinal properties are derived from the medicinal properties of the individual metals in the alloy. The ability of copper to relieve joint inflammation and pain is well known in natural medicinal systems, as is the antiseptic-like effect of zinc on skin disorders. Bishnu Saha says that the bell-metal vessels, at the very least, ease the symptoms of several ailments like gastric, diabetes and allergies; he says that regular use of vessels made from this alloy can have long-term effects towards preventing and relieving several ailments altogether. Between 200 and 300 people - all of them belonging to the same caste - in each relevant village make this cooking ware. There is a strong sense of community among these artisans, with each village having not more than 20 to 30 kilns (bhattis) where the bell-metal ingots are heated before being beaten into shape. This notion of sharing resources rather than competing for them is despite the fact that the artisans in each village specialises in the production of only a particular item: a village produces either cooking vessels, or bowls, or plates, or ladles. Naturally, as Bishnu Saha clarifies, despite the specialisation, most artisans can make all the various items - a person who makes bowls is of course equipped to make plates, and vice versa. However, they prefer to specialise in one particular item, and to experiment and innovate with shapes, textures and finishes. The artisans who make bell-metal cooking ware also make items only of brass or copper; however, bell-metal ware remains their speciality. Predominant items include kitchen utensils like cooking pots and pans; serving vessels and ladles; and plates, glasses and bowls to eat from and drink in. Cooking ware is the traditional bell-metal product made by the kansaris and remains the staple product.

Anklets worn by women over the years were the main products of Datia casting. Later, the numbers were reduced, as they were heavy. They were then converted into utility items by adding a plate underneath; for example ashtrays and boxes to keep knickknacks. The main feature of Datia is the jali work done on the sides of the product. Tikamgarh: Bell metal products from Tikamgarh are plain and solid in appearance with fine decorative work at certain areas. The products have a rustic appeal. These products do not have any resemblance to the jaliwork of Datia.

Berhampur Resham Patta Saree is a traditional product from Odisha. The "saree" is meant for women and the "joda" for men. Because of this famous silk work, Berhampur is also known as the silk city of India. The Berhampuri silk saree is unique due to its typical Odissi style of weaving and the “kumbha”, particularly “phoda”, temple-type design. The zari work border design is different from other such designs. The sarees also adorn the deities of Jagannath, Balabhadra and Subhadra at the Jagannath temple in Puri.

This involves the carving of intricate and detailed designs on the areca catechu betel nut. The subject matter ranges from popular deities to figures of animals and symbolic emblems. There is a strong element of religiosity in the carvings and figurative representations of gods and temples abound. Another range consists of jewellery and other bric-a-brac. Beads, rings, and other ornaments are common as are more utilitarian objects like key chains. Owing to the nature of the betel nut, the final product has an interesting speckled look. Dry betel nut of the size required is cut with a vice into different shapes and sizes depending on what it is to be crafted into. The craftsperson holds the cut betel with forceps and engraves it with a specially designed needle called munna, which is available in various sizes and thicknesses. A sharp-edged knife called tagi is also used. The engraved pieces are then filed and joined together where necessary. Some craftspersons use a small motor attachment to make the work easier. The product is then varnished. Known as the karungar, this craft was originally practised in Jaipur (Rajasthan). In fact, it was mentioned in the cataloguing of products for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888. It has, however, almost died out in Jaipur and is now practised only in small pockets.

This involves the carving of intricate and detailed designs on the areca catechu betel nut. The subject matter ranges from popular deities to figures of animals and symbolic emblems. There is a strong element of religiosity in the carvings and figurative representations of gods and temples abound. Another range consists of jewellery and other bric-a-brac. Beads, rings, and other ornaments are common as are more utilitarian objects like key chains. Owing to the nature of the betel nut, the final product has an interesting speckled look. Dry betel nut of the size required is cut with a vice into different shapes and sizes depending on what it is to be crafted into. The craftsperson holds the cut betel with forceps and engraves it with a specially designed needle called munna, which is available in various sizes and thicknesses. A sharp-edged knife called tagi is also used. The engraved pieces are then filed and joined together where necessary. Some craftspersons use a small motor attachment to make the work easier. The product is then varnished. Known as the karungar, this craft was originally practised in Jaipur (Rajasthan). In fact, it was mentioned in the cataloguing of products for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888. It has, however, almost died out in Jaipur and is now practised only in small pockets.

This involves the carving of intricate and detailed designs on the areca catechu betel nut. The subject matter ranges from popular deities to figures of animals and symbolic emblems. There is a strong element of religiosity in the carvings and figurative representations of gods and temples abound. Another range consists of jewellery and other bric-a-brac. Beads, rings, and other ornaments are common as are more utilitarian objects like key chains. Owing to the nature of the betel nut, the final product has an interesting speckled look. Dry betel nut of the size required is cut with a vice into different shapes and sizes depending on what it is to be crafted into. The craftsperson holds the cut betel with forceps and engraves it with a specially designed needle called munna, which is available in various sizes and thicknesses. A sharp-edged knife called tagi is also used. The engraved pieces are then filed and joined together where necessary. Some craftspersons use a small motor attachment to make the work easier. The product is then varnished. Known as the karungar, this craft was originally practised in Jaipur (Rajasthan). In fact, it was mentioned in the cataloguing of products for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888. It has, however, almost died out in Jaipur and is now practised only in small pockets.