The main centres for this craft are Cuttack in Odisha and Karim Nagar in Andhra Pradesh. Traditionally the ingots were beaten on an anvil and elongated into long wire by passing them through a steel plate with apertures of different wire gauges. Each filigree jewellery piece actually combines several component parts.The space within the frame is filled with the main ribs of the pattern which is usually a creeper or flower, forming itself into small frames of circles, flower petals, and the like. Karim Nagar in Andhra Pradesh has long been noted for its silver filigree work. This traditional craft requires delicate workmanship. The products made include ashtrays, boxes, cigarette cases, trays, bowls, spoons, pill boxes, jewellery, buttons, paandans,, and perfume containers in the shape of peacocks, parrots, or fish. The jewellery made here has twisted silver wire as the base material; the articles have a lacy, trellis-like appearance which gives them a rare charm. Two or three wires are wound together after heating and then bent into various shapes to get patterns. The components are fixed together by a special method in which small square strips of an alloy of copper and silver known as tankam are spread to make the entire design, and then placed on the furnace. When well heated, dry paddy husk is sprinkled on it; this bursts into flames and melts the tankam pieces. The molten tankam penetrates into crevices and ensures the firm binding of the small pieces that comprise the whole. The block is then cooled in cold water. The smaller articles are directly moulded into various designs. For larger articles, smaller ones are made and pieced together. The main ribs are first fixed and the interstices are filled in with delicate tendrils or circular pieces which gives the article its special character. Karim Nagar has its own unique patterns and the elaboration in filigree is according to the pattern. A design with a high level of traceries is known as the Karim Nagar design. This is visible mainly in the perfume containers made in Karim Nagar, a product for which the place is famous.

Sarkanda plant grown abundantly in the green state of Haryana during the season of winter it gets dried up, is harvested and is then put to creative usage by the local folk. The dried main stalk is harvested and creatively used to produce collection of products. The thicker parts are used to make stools and furniture while the outer skin is used as thatch. The tuli, top half and the leafy covering, moonj is made into baskets Changeri is one of the many moonj grass products which are popularly made by local women folk. It is a traditional shallow basket made by coiling technique and often with a lid. Besides the Changeri they make the large boiya roti/bread basket, that may or may not have a lid but nonetheless keep hot rotis dry and fresh due to its moisture absorbing walls. A variation of the changeri is the Sindhora a pear shaped basket that is bound with naulai or wheat stalk. These baskets are decorated with gota/shiny ribbons, colored threads, date palm and patera leaves. The women also make hand fans to keep the heat away and the indhi, used as a support base for carrying water pots on the head are also made of sarkanda as these form part of the bride's dowry and are highly decorated with colourful fabric and yarns and embellished with bead and shell tassels

These world famous wooden toys and carvings, dating back to the beginning of the 20th century, are produced at Channapatna, a small town near Bangalore in Karnataka. The lacquerware toys and dolls are made in different colours and are greatly appreciated by people both in India and abroad. The raw material is “hale”, a very soft and lightweight wood which is grown near Channapatna. About a century ago, there were very few types of lacquerware products and these had a crude finish. Later, the craft was refined and improved with the use of a metal turned lathe which produced lacquerware products with distinctive brightness by substituting lithopone for sulphur in the manufacture of colour.

Charakku, the king of vessels, is one of the largest cooking vessels to be cast by man. It is made of bell-metal, an alloy of copper and tin, and has a most attractive surface with an old gold tint that does not tarnish and needs no tinning. The moosaris, one of the six categories of kammalas, are the traditional metalsmiths of Charakku. They trace their origin to Vishwakarma, the deity of all craftspeople. They use the cire perdue or lost wax method of casting. Elaborate rituals and the propitiation of the gods traditionally accompany the casting. These high cauldrons/charakkus have a diameter of almost five feet and are wide and shallow. They have handles on either side for ease of lifting. These vessels are used on ceremonial occasions to prepare payasam in large quantities. The process of making the clay mould is so elaborate and laborious and the outcome of the solid metal mould so dependent on precise and careful handling of both the mould and the molten metal that special prayers and rituals are conducted to ensure a perfect result. Smaller items like lamps and small vessels are also crafted by the artisans.

This is an ancient craft - chariots have been used for ritual processions during many of the festivals that are celebrated with great fervour and intensity in Nepal. These include, among others, the Janabala dyo procession in March, the Bsket Jatra in April, and the Rato Machendranath Jatra in May.

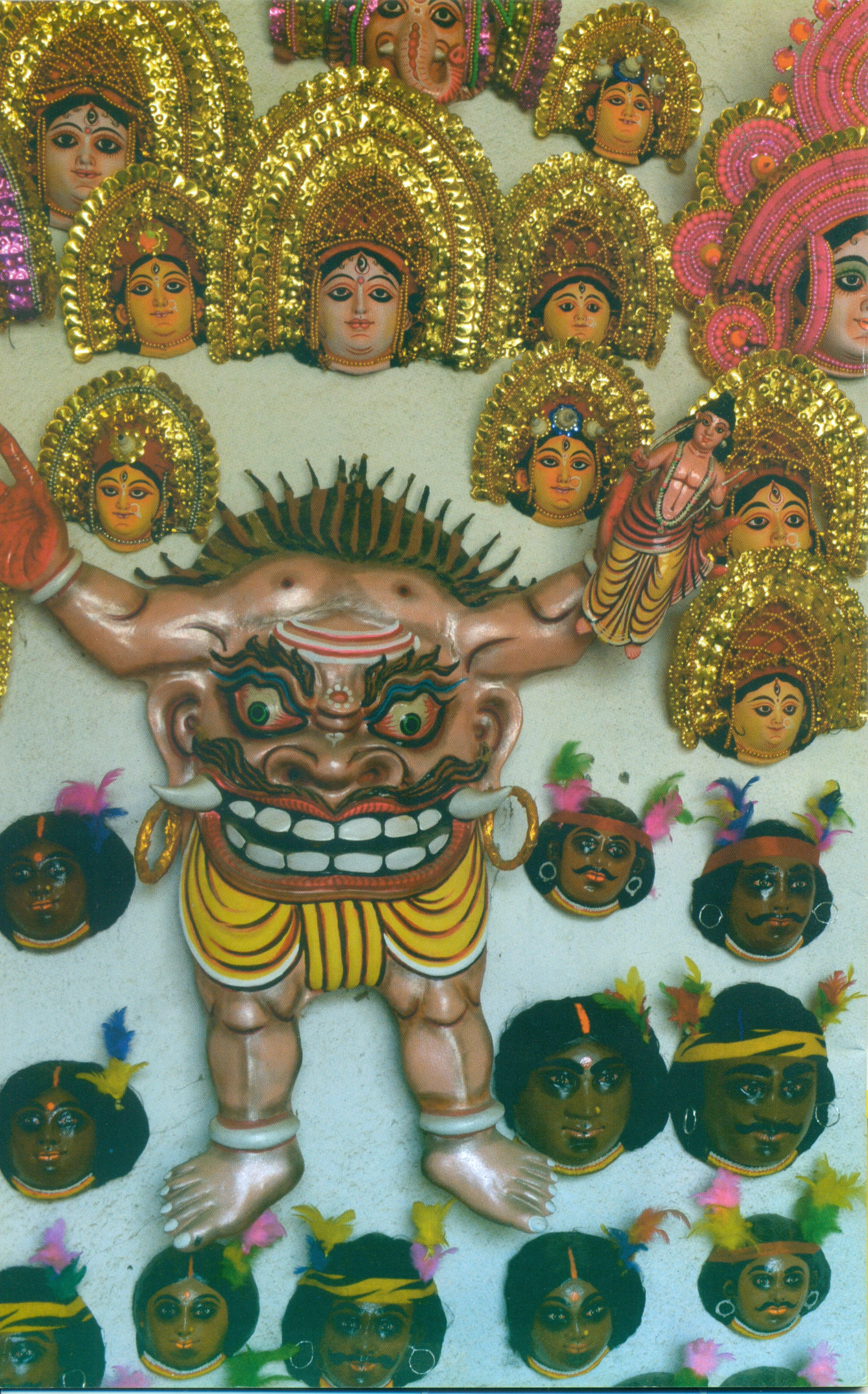

The art of Chau mask making is around 150 years old. This began during the reign of King Madan Mohan Singh Deo of Baghmundi in Charida district of Purulia, West Bengal. These masks were used in Chau dance, which is a martial art and involves vigorous movements. Charida village home to chau mask makers is in Purulia district which is a part of Chota Nagpur Plateau. Making of Chau Masks: Paper pulp and clay are used for making these masks. The materials of making masks are collected locally. Adornments are done with feathers and beads. Tools like Thapi, a small wooden tool is used fro finishing and brushes are used for colouring the masks. The masks are elaborate and and ornamental. They usually depict mythological figures like goddess Durga, Ganesh and demons. They also depict lions, tigers, deers, monkey, peacock etc. Today these masks are made in small size to be used as home souvenirs and decorative objects.

Chendamangalam is a village of handloom weavers in the Ernakulam district of Kerala. The basic raw materials used for the weaving of Chendamangalam Dhoties are a fine count cotton yarn and “kasavu” (zari).The speciality of the dhoti lies in preparation of the warp threads through street sizing. After sizing, the warp threads become almost round and uniform in shape, giving the dhoti a very clean surface without any protruding fibres on it. Borders are patterned with “kasavu”(zari).

The Chettinad Kottans were originally palm-leaf baskets woven in the Chettinad region. This hand-woven basket is woven from strips of palm leaf in the traditional, very distinctive weave pattern. Chettinad basketry has been noted for its unique style and colours. The raw material used is the locally available palm leaf. The process of making the basket involves harvesting of palm leafs, storage, dyeing and weaving. The traditional kottans were used mainly for packaging and as containers for gifts and other articles.

Chhau dance is a folk performance of Puralia, West Bengal. Although it is practiced in other regions of India, they have their distinct and unique features. Chhau Dance in Purulia and Seraikella is performed with a mask. The performance is accompanied with colorful costumes which match with the mask and complete a performer’s attire. The costumes are mostly made of silk. The dance is enacted through mythological stories, epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata and is devoid of any dialogue. It has dance, drama and music. It was primarily a war dance and constitutes of vigorous movements. Chhau dance is only performed by males, no women participate in this dance form. Even the role of women is played my men in disguise. Traditionally, the dance was performed in front of Shiva temple or village square. Today, Chhau dance has found its way to the global stage and is representative of the Bengali culture.

In the hot and dusty plains of North India, chiks have traditionally been used to keep out the dust and blinding heat of the hot summer months keeping the interiors of homes and workplaces cool. This simultaneously utilitarian and decorative product was used widely during Mughal times as screens and partitions in the zenana/women's quarters. The use of chiks was also wide spread during British times but they were mainly of the rougher variety to be used in verandahs and outer public areas. This traditional craft has its roots in the districts and towns of Uttar Pradesh and Delhi. In Delhi the chik makers can be found in Kichripur, Govindpuri and Ashram Chowk.

Chiks are made from bamboo splits or rigid stems of sarkanda grass, held in place by a warp of cotton threads that are finely spaced to create a blinds and screens which can easily be rolled up but not folded or gathered.

Using either Bamboo splits, locally known as tilli or the lower parts of the wild sarkanda grass stems that are sourced from riversides and swampy regions near Delhi and from Meerut in Uttar Pradesh; doubled cotton yarn are individually wrapped around the rigid sarkanda or bamboo splits. To add strength and give a finish the chiks are edged on all sides with a nivar/woven tape. Most are additionally lined with cotton fabric to make them opaque and reduce the sunlight that filters through. Outdoor bamboo chiks that are usually heavier and more sturdy are usually lined with waterproof backing.

Traditional chikankari was originally embroidered with white thread on muslin cloth. Gradually, other fabrics were used as the base; these included organdie, mulmul, tanzeeb, cotton and silk as well as voile, chiffon, linen, rubia, khadi handloom, terry cloth, polyester, georgette. Chikan is essentially a white-on-white embroidery, that is to say white embroidery on white fabric. Predominantly floral designs are executed on fine cotton with untwisted threads of white cotton, rayon or silk. This style of embroidery has evolved over the centuries, reaching its peak in the late 19th century in Lucknow. True chikankari has the unique property of being limited to a fixed repertoire of stitches, each of which is only ever used in a certain way. This repertoire consists of 32 stitches (five of which are common to other forms of embroidery), five derivatives and seven stitches that form an embossed shape, usually a leaf or petal. These small individual petals help identify chikankari. The making process has five different stages, such as cutting, stitching, printing, embroidery, washing and finishing.

The chindi dhurries are so named as the weft strips are created by shredding of cotton fabric or leather strips termed as chindi. A striking feature of the dhurrie is its warp is spun cotton yarn while weft is unspun cotton (chindi) that gives dhurrie a striped look. The Chindi dhurries are identifiable by their characteristic stripes in bold solid colours of red, blue, green and purple etc. The chindi dhurries are now mostly produced in Maharashtra and also in Uttar Pradesh. The raw cotton yarn is procured from Delhi and Agra. The dhurrie making process is flexible and the horizontal loom can be adjusted to make large or small dhurries. The adaptability of the dhurrie weaving process has led to many inventions. Now dhurries are also woven in interesting geometric patterns with bright colours. The art of chindi dhurrie is similar to Panja dhurrie weaving as it uses the same tool (panja) to keep the yarns tight while weaving. The warp is stretched between the two horizontal beams, which can be adjusted according to the size of dhurrie required. The chindi is inserted in the warp yarns with fingers according to pattern on graph. Dhurrie can easily be reproduced in many sizes and colours. Dhurrie weaving in Maharashtra has come out as an important economic activity. These dhurries most commonly adorn the living rooms and bed rooms and find very important use in the prayer rooms.

The Ansari women of Timli village weave chindi or rag durries. The durries are colorful cotton rugs with wefts made from strips of waste fabric and rags. The women make them on pit looms in their homes. The villagers taught themselves how to weave and occupied many women.

Chitaris is the Marathi word for a painter. A large number of chitaris settled in Nagpur, drawn there by the liberal patronage of the rulers of the Bhonsale dynasty who celebrated Hindu customs and traditions with great pomp and reverence. These chitaris made their homes in the Mahal areas of Nagpur and even today their descendants are found to be living there in a lane known as Chitari Oli. The chitaris' work consists of making objects required during Hindu festivals. The rituals connected with them often require readymade artefacts in wood, clay, and paper. Ganpati has a special significance and the chitaris produce clay images for installation during the Ganpati festival. Over the years changing tastes have lead to a decline in the demand for their work. Today there are only a few families practising in Nagpur. They have now taken to various types of decoration work, including contracts for erecting decorative gates in the city during festivals and marriage decorations. The chitaris work throughout the year except in the summer months when they turn their hand to making marriage platforms and bowlas or conical temple-shaped pavilions for marriages. Different chitaris specialise in different forms and products. Some specialise in the making of three-dimensional idols, chiefly of Ganpati. During the slack seasons they cater to the city shops by creating mannequin figures for draping garments for display. Another group specialises in pata-chitra or paintings on paper and cloth. Among the popular subjects are the jiwti-pata, gajalaxmi-pata, and the nagpanchami-pata. Yet another category of chitaris makes rupdas or the paper masks for Ramlila dramas. During marriages the chitaris are also invited to decorate the facades of the houses with representation of Ganesh, his consorts Riddhi-Siddhi, horse- and elephant-riders, and floral borders.

Chittaras are intricate wall paintings traditionally created by the tribal women of Malnad on their red mud-coated houses, as well as rangoli floor designs. Chittara paintings are part of a larger context of creativity and celebration in the cultural milieu of the region. The chittara art-form however was almost extinct till it was revived recently by Eshwar Naik and his sister Lakshmi, Malnad tribals, who 're-discovered' the artistic and cultural tradition of their forebears (their mother was a skilled chittara artist, with a rich repertoire of songs and music in which the art form was grounded. Eshwar Naik set up a training centre for chittara art, and is focusing on documentation work.

-

White is derived from a mixture of rice (threshed and pounded rice, made into a paste) and white mud

-

Red is made from crushed stone and the abundant red mud in the region

-

Black is also made from rice, which is burnt and then pounded

-

Yellow is made from the seeds of the gurige tree, special to Shimoga and Sagar districts in Karnataka.

The chunari, a wave-patterned Newari textile that was traditionally a must for wedding ceremonies is now a relatively rare sight. Used during the wedding function in Hindu Brahmin and Kshatriya farmer's homes, the chunari was used as an auspicious wrapping for the dowry gifts taken by the newly-wed bride to her husband's home. Among the Newars, especially of the sakya caste, the chunari fabric was used to wrap up the nuts, pills of keshari, and other items in a bala or brass bowl that was sent along with the bride to her new home. Chunaries were dyed by the chippah caste; however, these textiles are now almost a thing of the past.

The Chutka is a w woven blanket with a shaggy pile, woven and used by the Shauka tribes living in the frontier villages of the north. It is used to sit on and as bedding. It is extremely heavy and thick and weighs between 3 to 4 kilograms. making it a wonderfully effective to withstand the cold and feel cozy and warm.

The Chutka is woven differently in Garhwal and Kumaon.

In Garhwal, the weavers use a verticle loom on which they also weave carpets called dan. Traditionally, the chutka was woven in backstrap looms and the practice continues in some villages in Kumaon.

In Kumaon, the chutka is very often woven on a floor and horizontal loom operated on treadle.

The Chutka is woven differently in Garhwal and Kumaon.

In Garhwal, the weavers use a verticle loom on which they also weave carpets called dan. Traditionally, the chutka was woven in backstrap looms and the practice continues in some villages in Kumaon.

In Kumaon, the chutka is very often woven on a floor and horizontal loom operated on treadle.