For generations, Nepali craftsmen have been making beautiful metal objects - ranging from ornate religious statues and temple decorations, to household vessels, pitchers, cups, and bowls - using the lost wax method. The focus of documentation has traditionally been on the unique bronze statues and there is comparatively little information on the production of simple domestic brass and bronze cast items used in everyday life created using the lost wax method. Household metal utensils like karuwa (water pot with spout), ankhora (water pot, bowls), kasaundi (rice cooking pot), surahi (wine jars), etc. are made by the casting process. They are mainly cast in bronze. The decorated ankhoras and karuwas are unique and the Karuwas of Palpa and Bhojpur districts are famous for their skill in decorating them. Faced with stiff competition from inexpensive, machine-made products, many of the craftsmen over the past few decades have switched to other professions and families that had once passed on these skills to their children have stopped doing so. Thus, the tradition of making these household products by hand is gradually fading away. Though hope lies in the fact that, if it can be afforded, most Nepalese prefer using bronze utensils - believed to be better for a health. Bronze maintains the temperature of the food kept in it, does not leave the taste of the metal in one's mouth, and is durable and long lasting. It also fetches a reasonable price when re-sold.

The Nepalese ritual and traditional icons of bronze and copper are famous the world over. The numerous art works in museums and personal collections reflect the superb skill and workmanship of the masters who produced them in the past. This great talent has been nurtured till today by not only the demand within Nepal for sacred and ritual icons but also by buyers from all over the world. These pieces are cast in the lost-wax or cire-perdue process. The technique involves the moulding of beeswax into the desired form, after which the wax is covered with a layer of fine clay and rice-chaff mixture. Meanwhile clay is also deftly tucked inside the image. Once the clay is heated, the wax melts out through a hole in the bottom to leave a hollow mould, hence the name 'lost wax'. When molten bronze has been poured inside and has cooled, the mould is broken and the piece released for further refining. Each piece is therefore unique and individually cast.

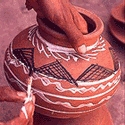

The potters of Himachal Pradesh originally belong to Jammu, Rajasthan, and Punjab and are concentrated mainly in the villages of Kangra, Mandi, Kulu, Chamba, and Shimla. Their place of origin distinguishes their style of working. These potters are locally known as kumhars, kumbhars, or prajapatis, and trace their descent from Lord Vishwakarma. Kangra district is well-known for its distinct red and black pottery. The pots are embellished by painting on them with the traditional white and black colours or by inscribing popular linear and circular patterns with a knife mainly before firing. The products commonly made include pots of different shapes and sizes. These are used for storage and ritual purposes. Diyas or lamps, toys, and figures of Hindu deities are shaped by hand or moulded and then painted in gay colours for the festive season. Kangra in Himachal Pradesh has clay ware in black or dark red colours. The products made are mainly for domestic use: gidya jugs for milk or ghee, patri bowl for curd or butter, and nareles or tobacco-smoking pots.

The earthen pots of Chowra are hand-shaped by the women, with clay taken from the neighbouring island of Teressa. These are low fired using sticks and leaves. The finished pots have a smooth, shining surface and a pattern of thick, dark, chocolate-brown stripes obtained from the juice of the tender coconut husk, which is applied before firing.

Traditionally, the toy industry in Pondicherry used clay; now the material used is papier mache and Plaster of Paris. The craft is concentrated largely in Kosapalayam, a village near Pondicherry town. The toys depict all aspects of Indian life. They are beautifully moulded and attractive in appearance. The craftspersons belong to the kuyavar and kosavar community. The dolls represent different Hindu deities in diverse postures or as symbols of different characters. The style as well as colouring is natural. Figures that are part of ceremonial occasions are shown in orange or rose colour and grey is used to show those engaged in personal labour. If it is a marriage procession, the bride and groom are in orange or pink while the band, the torchbearers, or those carrying gifts are in grey. Passengers riding a vehicle or horse will be in orange or pink. In the case of Plaster of Paris toys, the entire surface is finished with only one colour --- white or cream or pale blue. The jewels and special clothes of deities are splashed with gold colour.

Kumbhara community from Kannipatakka village bring clay from the ponds nearby to shape it into various traditional daily products like water pots, flower pots, animal figurines like elephants and horses. The recent years have seen diversification in the clay products like sculptures in different sizes and products with decorative elements have become more popular.

Assam has a rich tradition of terracotta which has been handed down from generation to generation. There are two traditional potter communities - Hira and Kumhar. The kumhar potters use the wheel and create figurines of gods and goddesses, clay dolls, toys, and pots. Whereas, the Hira community do not use the wheel at all and manufacture household articles using the compression method. Among the Hiras, only the women are engaged in pottery while the men help in procuring raw materials and selling the wares.

The most commonly used pottery products include earthen pots and pitchers, plates, incense-stick holders, and earthen lamps. In Kamrup, terracotta objects including clay tiles are made. Asharkandi, a village in Goalpara district, is famous for its graceful clay dolls. Today, the traditional products are still being made but new shapes and products are also being tried out.

The tradition of clay and terracotta in Bihar dates back to the Mauryan period when hundreds of male and female figurines and animal figures --- horses, elephants, birds, and reptiles --- were made of clay and baked. This tradition continued down to the Mughal period. Each village, district, and region has its own style of pottery and of decoration. The some rituals continue to be practised in their original form. The making of toys and images was --- and is --- closely connected with seasonal festivals and other religious ceremonies. In the past, clay village gods or gram devtas could be seen outside each village, guarding the inhabitants against bad luck, illness, and the wrath of nature. Clay elephants, signifying marriages, could be seen on the roofs of houses. These figures were not merely religious but also served as toys for children and decorations in bed chambers. Sometimes they were hand-modelled, while at other times they were moulded. Today, the potter's art in Bihar is confined to medium and coarse red wares and the making of dolls and toys on festivals and special occasions.

Votive terracotta figures are found widely in the districts of Bastar, Jhabua, Sarguja, Raigarh, and Mandla. Clay icons are placed on the borders of villages to ward off evil spirits, to appease and propitiate unseen forces, and also to seek their blessings for a trouble-free and happy life. Icons of Matri Devi or the Mother Goddess, known as Mai among tribals, are installed and propitiated to guard villagers from plague, fever, and epidemics. The idols have various names, linked to the name of the village: Khanda Mai, Banjarin Mai, Kankalin Mai, and Chechak Mai. The tribals of Bilaspur have animal and human figures on their roof tiles. The Baigas and Gonds of the Mandla region make figures with sunken eyes and big noses, with their head covered with animal hairs. These are linked in some form with witchcraft and evil spirits and are placed in fields or on roof tops as protection. Sacred spaces under trees also have votive terracotta offerings. A wooden pillar intricately carved with figures of gods and animals is installed in the central courtyard of temples, known as the devgudi. Clay images of gods and goddesses are also installed in the temples. Propitiation of the deities is done with votive terracotta offerings. Horses are a common form of terracotta figurines. The terracotta elephants of Chindwara are depicted with two riders sitting on a howdah. Howdah elephants are crafted in Bastar, Mandla, and Betul. They are sometimes used as the sinhasan or seat of the Mother Goddess. Betul specialises in animal figures. The mud walls of houses are adorned with clay murals, clay relief, or carvings, usually done by women. Clay is mixed with paddy husk and cow dung in this process, and the motifs are include traditional chauk or square motifs and animal figures on the internal and external walls of the houses. This relief work is bare and unpainted. In Rewa and Shahdol, life-size figures of gods and goddesses like Ganesha, Hanuman, Shiva, and Kali, depicted on the interior walls of the houses, give them a temple-like aura. The facial features are finely carved and embellished with fine lines. Tribal terracotta masks form a part of all community celebrations and are very popular in the regions of Bastar, Sarguja, Mandla, and Betul. The Chher Chhera festival is celebrated with young men and women wearing masks dancing and singing. Clay masks are made out of clay pots or matkas with holes for eyes and with clay noses stuck on them. Masks are coloured red and are used in folk plays and dances. Matkas turned upside down with bold and grotesque features are seen fixed on bamboo poles in fields acting as scarecrows. The tribal groups of Sahariya, Gond, Baiga, and Pardhan make attractive grain storage bins embellished with carved animal and human figures. Lamps or diyas are also common terracotta products. The famous chidiya diya of Sarguja is a complicated wheel-thrown oil lamp and works on the siphon principle. The bird's belly is detachable and has a tube-like opening by which it is filled with oil. Since it is kept lit at the devgudi of the Mother Goddess, it is known as Mata Diya or Mother Lamp.

A variety of earthen objects such as pitchers, flower vases, pots, cut-work lamps, Matka-water pot, Surahi- the narrow necked pot, Gamla- flower pots , lanterns, cutwork lamps, Handi-cooking utensil, Parat-larger platters, gulaks, chillums, handis, musical instruments Diya-oil lamps, Aarti lamps used in rituals, idols and figures of gods and goddesses, large garden pots, patterned tiles, roof tiles, urlis, etcall made of light red clay which boasts a cooling effect can be found in abundance.

A large number of the potters in Delhi have migrated from the neighboring states of Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh Rajasthan. They are located in Govindpuri and Hauz Rani: Kumbhar Basti. A number have settled in the Prajapati Colony in Uttam Nagar that was set up in the 1970’s to house the potters. As most of the potters had names connected with their caste occupation the colony was called Prajapati. Currently over 400 families practicing this craft in the colony and provide their products across Delhi and NCR.

The methods adopted by the potters are similar to those employed in the pottery tradition(s) of their ancestral place. Black, red, and yellow clay in the form of small pieces is obtained from Rajasthan and Delhi. This is mixed and dried, after which water is added to it. The resulting mixture of wet clay is filtered through a fine sieve to remove pebbles. After the clay has been kneaded into homogenous flexible dough, the prepared clay is made into a variety of artifacts using either the throwing technique. Coiling technique is used in making large products that are too large to be thrown on the wheel and to make those with shapes that cannot be turned on the wheel. After giving shape to the item and drying it in the shade, it is baked in the kiln. The potters specialize in making particular products and have specialize in what they do.

Their tools are rudimentary and include the the Kumbhar chaak or potter's wheel, the electric wheel, the Khuriya or turning tool, the Mogri wooden mallet , Sua or incising needle, the Thapi wooden beater, Thapa – the large beater, Maniya or die and the Katni carving tool.

Goa earthenware, with its deep, rich, red surface has a charm and style of its own. The North Goa districts of Bicholim and Calangute are well known for its red clay pottery traditionally done by the Kumbhar community who now have added stoneware products to their repertoire. Making both utilitarian products for cooking and storing liquids - such as pots, bowls, plates and vases, they also craft items like lamps, idols, sculptures, planters, large figurines and masks for sale. The red clay is obtained from the fields in Bicholim then kept in water for two days and sieved through a net till a fine homogenous mixture is obtained. It is left to dry for 10 days till it is ready for kneading. The processes used include throwing, coiling, beading, pinching, sculpting and manipulating the clay to form the object. The Kumbhar also use the processes of moulds, clay slip as joinery and slab casting when needed. Local kilns are used for firing. The terracotta objects are fired in a kiln and cooled for a day. The products are sold at Mapusa and in weekly market in Panaji and Madgaon.

Kutch and Saurashtra in Gujarat are noted for their beautiful pottery. The ware is white, with delicate designs on it. Bhuj in Kutch has a colony of potters producing clay utensils, tea kettles, bowls and pots for water, miniature toys, grinding stones, furnaces, and griddles. Festival objects like toy elephants, bullocks, and horses are also made by hand. This region is also noted for large grain containers. The pottery has a distinctive pale creamy colour. Relief work is done on it with mirrors and motifs. In Saurashtra, votive terracottas of horses, elephants with riders, calves, and goddesses, as well as imaginative versions of the deity Ganesha are done by hand. The handmade figures are moulded by women, and the wheel is by manned by men. This region is noted for its gopichandan --- clay which is the colour of sandal wood --- from which buff coloured pottery is made. Clay utensils with a lac coating are crafted by the tribals of the Chota Udepur region. Botad village in Bhavnagar is noted for clay whistles, clay bells, and clay buttons . Gujarat has a unique tradition of votive terracotta, that follows from the Indus family heritage. Figurines of animals and humans are made from clay and coated with lime. They are then painted upon and are often placed in shrines and sacred groves. The raw material of these products is the mati- red clay, also called terracotta. After the pounding and preparation of the clay, it is moulded by the use of a charkha (spinning wheel). After the moulding, the clay is hand modelled with unique and intricate designs that are very akin to the hand embroidery done on the textiles.

The kumbhar potters of Haryana are known for their slim-necked pitchers called surahi. These water pots serve to keep the water cool. The surahis of Jhajjar and Chawani Mohalla are especially famous as the water contained in these surahis acquires a special taste due to the quality of the clay available in these low lying area. Made from a combination of thrown and moulded parts the entire families participate in the craft process beginning with the preparation of the clay by the women and the youth. The men sit on the wheel to create the wheel-thrown surahi necks. For the round base, the clay is rolled and stretched over an upturned pot and then pressed into semi-circular terracotta dies that are engraved with patterns. After these semi-circular segments are half dry they are joined together with wet clay and left to dry in the shade. At this time the clay shrinks, leaving the surface of the die. Then the women attach the spout, neck and handles. The surahis are dipped in a slip made of barmi and sunaihri, the red and yellow clay, dried again and fired in mud kilns. Besides the surahi the potters of Haryana produce a large variety of terracotta products such as other water pots that are used not only to cool water but also used as ritual vessels for Hindu rites in kuan puja as well as during birth and death ceremonies, oil lamps/ diya, Grains storage pots, Flower pots, piggy-banks and tea cups/ kulhars, bowls of all sizes and use, musical instruments, clay toys, human and animal figures, plaques, medallions, and wall hangings. Two-toned vases, decorative pitchers, and lamp bases with shades of black and terracotta colors are popular. While there are potters in almost every village the potters of Jhajhar Bahadurgarh and Faridabad are the most well known

The tradition of clay and terracotta in Bihar dates back to the Mauryan period when hundreds of male and female figurines and animal figures --- horses, elephants, birds, and reptiles --- were made of clay and baked. This tradition continued down to the Mughal period. Each village, district, and region has its own style of pottery and of decoration. The some rituals continue to be practised in their original form. The making of toys and images was --- and is --- closely connected with seasonal festivals and other religious ceremonies. In the past, clay village gods or gram devtas could be seen outside each village, guarding the inhabitants against bad luck, illness, and the wrath of nature. Clay elephants, signifying marriages, could be seen on the roofs of houses. These figures were not merely religious but also served as toys for children and decorations in bed chambers. Sometimes they were hand-modelled, while at other times they were moulded. Today, the potter's art in Bihar is confined to medium and coarse red wares and the making of dolls and toys on festivals and special occasions.

Pottery is an age-old Indian tradition and the demand for it has never dwindled. In south India terracotta pottery has attained a high level of perfection. The potter is a member of almost every village community. The principal tools employed by this craft are the wheel, a convex stone, and series of flat mallets for tapping vessels. Red clay is used most commonly in manufacturing flower pots, images of gods and goddesses, and animal shapes. Sometimes the potters used reduction firing to give the pots an uneven black colour. Another interesting and less well-known use of the potter's wheel is the production of country roofing tiles which are molded in the form of cylinders and then split in half with a knife. Principal pottery cluster in Karnataka is in Kodagu district. They make small handmade terracotta toys and they also make bricks which are sold in local towns nearby.

The tribal groups found in these areas are Bhils, Bhilalas, Barelas, Patalias, Nayaks, and Mankas. Jhabua is known for votive horse figures. Horse figures, solid or hollow, are painted ochre and white. The white surface sometimes has red dots. Figures are crafted by making cylinders and then joining them together. Folk idols of the goddess Lakshmi are in great demand during diwali time. Bhils and Bhilalas of Jhabua make clay temples called dhabas, ranging in height from 1 cm to 1 m. These are offered with terracotta horses at the village shrine. The top of the dhabas are decorated with a kalash or a circular pot-like motif. The dhaba has a small door through which a diya or lamp can be placed inside. Horse figures are offered to the deities two days before Diwali (on dhanteras and kali choudas or diwali) and between the months of April and June ( chaitra and vaishakh). A community meal is organized. Clay horses are also offered to ward off evil spirits from the fields and to seek blessings for a bumper crop. Terracotta from Jhabua has crude, solid, and plain figures. Hollow terracotta figures are big and stylised. Life-size figures of sargujas are made. The figures are painted with white chalk and ochre. Mandla terracottas show tantric influences and figures from Betul have form and variety. During Diwali, terracotta idols of the goddess Mahalakshmi, and of gaulang or elephants and horses with riders are molded as solid figures, washed with lime and painted brightly. The region also specializes in making terracotta heads of Gangaur, a local form of Goddess Parvati. These heads are fixed on poles and adorned with clothes. Cylindrical figures of Gangaur idols are made and installed in houses during the month of chaitra. Adla pakshi or love birds is a popular figure in this region; the heads of the love bird are attached to a common cylindrical body with a pair of wings and are a symbol of inseparable lovers. The toys are handmade and are either hollow or solid. They are made usually by women. Animal figures like horses, elephants, dogs, lions, birds, deer, and bulls fixed on wheels are very popular with children. The sizes of the figures are usually small. Solid figures have a lot of variety and are more popular than hollow ones. Artisans also make hollow bird whistles. Some utility products include; Kuldi- pot for water, Chhalki- vessel for making curd, Bhutia- for storing toddy, Warya- for tapping male toddy tree, Faalna- for tapping female toddy tree and Wahaadi-small ritual vessel with a spout.

A number of pottery units in the Garo Hills are engaged in the production of clay utensils; these occasionally produce toys and dolls as well, particularly at the time of various festivals and religious functions in the area.

Clay figures are made all over Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry. Traditionally each village is guarded at its entrance by an enormous terracotta horse, which is the horse of Ayyanaar, a religious figure, the gramdevta of the village and its protector against all evils. Aiyyanar has an enormous moustache, big teeth and wide open eyes that keep constant vigil. Ayyanaar stands at the entrance surrounded by his horses and commanders or veerans. Ayyanaar figures, which include the horses in the army, range in height from less than a metre to over 6 metres. They are some of the largest terracotta figures to be sculpted and are painstakingly made by mixing the moist clay with straw and sand for a proper consistency. For the horse, four clay cylinders are rolled out with a piece of wood, for the legs, after which the body is built up gradually. The accessories, such as bells, mirrors, grotesque faces (kirthimukha) and crocodiles (makaras), are made separately as is the head. The parts are joined together on the auspicious tenth day, when the figure of Ayyanaar seated on the horse is given its features. This is then baked in a rustic kiln of straw and verati or dried cow-dung which is then covered with mud. Parts of the larger figures have to be fired separately, joined together and fired again. The faces are sometimes painted red to denote anger and the neck blue to denote calm. The rest of the body and decorations are also painted in bright colours. The oldest Ayyanaars and horses are found in Salem district. Salem and Pudukottai districts make the most large terracotta horses; the smaller figures, human, divine and animal, are made all over the state. Given the time taken by the firing process, moulds are becoming popular to hasten the process. Ayyanaar figures are found in the village sanctuaries of Chettampatti and Nallur (Tiruchirapalli district), Tirripuyanam (Madurai district), and Vadugapalayam (Coimbatore district). Most of the other village deities are also made of terracotta. The temples found in the village are usually for the mother goddess or ammankovil along with a temple to the deity Ganesha or Pillaiyaar. Another important terracotta shrine is the naaga or serpent shrine, situated under a pipal tree near an anthill. It is made of clay with an intertwined body and is worshipped for its power of protection and rejuvenation. On Vinayaka Chathurthi clay Ganeshas are made and sold everywhere. These range in height from a few centimetres to a metre and they are glazed, painted, baked or often unbaked. The models are immersed in wells after the festival, and the unbaked form is preferred as it crumbles easily. Other products crafted include water drawing and storing pots and cooking vessels. During the harvest festival of Pongal old pots in the house are replaced by new cooking pots, vessels for storing grain and a new container for the auspicious tulasi/holy basil plant. The pots symbolise continuity of life, creation, destruction and rebirth. In Tamil Nadu, potters are known as kuyavar, kulalaar or velar and they trace their origin to Vishwakarma, the divine craftsman himself.

Clay figures are made all over Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry. Traditionally each village is guarded at its entrance by an enormous terracotta horse, which is the horse of Ayyanaar, a religious figure, the gramdevta of the village and its protector against all evils. Aiyyanar has an enormous moustache, big teeth and wide open eyes that keep constant vigil. Ayyanaar stands at the entrance surrounded by his horses and commanders or veerans. Ayyanaar figures, which include the horses in the army, range in height from less than a metre to over 6 metres. They are some of the largest terracotta figures to be sculpted and are painstakingly made by mixing the moist clay with straw and sand for a proper consistency. For the horse, four clay cylinders are rolled out with a piece of wood, for the legs, after which the body is built up gradually. The accessories, such as bells, mirrors, grotesque faces (kirthimukha) and crocodiles (makaras), are made separately as is the head. The parts are joined together on the auspicious tenth day, when the figure of Ayyanaar seated on the horse is given its features. This is then baked in a rustic kiln of straw and verati or dried cow-dung which is then covered with mud. Parts of the larger figures have to be fired separately, joined together and fired again. The faces are sometimes painted red to denote anger and the neck blue to denote calm. The rest of the body and decorations are also painted in bright colours. The oldest Ayyanaars and horses are found in Salem district. Salem and Pudukottai districts make the most large terracotta horses; the smaller figures, human, divine and animal, are made all over the state. Given the time taken by the firing process, moulds are becoming popular to hasten the process. Ayyanaar figures are found in the village sanctuaries of Chettampatti and Nallur (Tiruchirapalli district), Tirripuyanam (Madurai district), and Vadugapalayam (Coimbatore district). Most of the other village deities are also made of terracotta. The temples found in the village are usually for the mother goddess or ammankovil along with a temple to the deity Ganesha or Pillaiyaar. Another important terracotta shrine is the naaga or serpent shrine, situated under a pipal tree near an anthill. It is made of clay with an intertwined body and is worshipped for its power of protection and rejuvenation. On Vinayaka Chathurthi clay Ganeshas are made and sold everywhere. These range in height from a few centimetres to a metre and they are glazed, painted, baked or often unbaked. The models are immersed in wells after the festival, and the unbaked form is preferred as it crumbles easily. Other products crafted include water drawing and storing pots and cooking vessels. During the harvest festival of Pongal old pots in the house are replaced by new cooking pots, vessels for storing grain and a new container for the auspicious tulasi/holy basil plant. The pots symbolise continuity of life, creation, destruction and rebirth. In Tamil Nadu, potters are known as kuyavar, kulalaar or velar and they trace their origin to Vishwakarma, the divine craftsman himself.

Melaghar and Palpada village of West Tripura district are known for their special pressed clay work. About fifty families in these villages are making and marketing these painted clay work. Traditionally wheel based pots and utensils and handcrafted by the villagers who have diversified into other objects of skill and dexterity. Potters now also make small items of utility like oil lamp, flower vases, decorative wall tiles and pressed functional roofing tiles. Statues of popular gods and goddesses are a great attraction in fairs and festivals. The technique is to use a process of press forming inside moulds made of plaster-of-Paris that are cast over a well crafted original piece. Another significant skill of the potters of Tripura is to make dies and moulds. Clay baked die are popularly used in the preparation of milk sweet called sandesh .