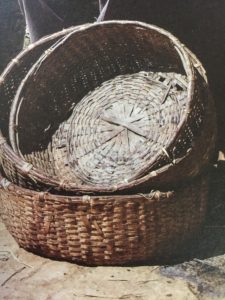

Craftsmanship in Tripura is a unique blend of styles practised by different tribes and communities belonging to diverse religions. In its weaving, too, the region shows a similar fusion of styles, where the traditional patterns have meshed with Manipuri and Bengali styles brought in by craftspeople from these regions who have settled in Tripura. There are 12 major species of bamboo used in the region and each region and every tribe has its own use for the plant. The tribes, with a rich and varied culture, belong mainly to the Riang, Chakma, Halam, and Usai communities. The majority of tribals live in elevated houses of bamboo called 'tong'. The cane and bamboo handicrafts of Tripura are known for their elegance and exquisite designs. Bamboo is used to make furniture, panelling, mattresses, baskets, lamp shades, bags, moorahs, baskets, vases, mugs, pencil holders, tablemats, and other mat products. The tribes of the Northeast use baskets to transport and store a wide range of goods for day to day living --- firewood, water, chickens, grains, ornaments, and thread. A very high degree of skill is required to make the fine and perfectly woven baskets. Cane and bamboo are split vertically and made into extremely fine and uniform strips, using simple tools. The waxy top layer is used while the inner layer, which is fibrous and rougher than the outer layer, is removed. The bamboo is then stripped down to the required thickness and length. The splits are dextrously woven to form a large array of forms and shapes. Artisans also produce smaller versions of utilitarian items with very fine bamboo splits. These come in an infinite variety of weaves and are exquisite. In western Tripura men can be seen weaving the kula, dala, and tokri to store vegetables. Winnowing trays and fans are formed by making a mat into the desired shape. Every third strip uses the outer layer of bamboo. Pollo, a fish trap, is made of bamboo splits that are 6 mm by 4 mm in cross section. Sudha is a fish trap used by the Jamatia tribe of Tripura. It consists of a bamboo net suspended from crossed splints. Dulla is a commonly used fish basket. Pathee is a rain shield similar to the japi of Assam. Mats and mat articles like the bamboo 'chatais' are also among the well-known crafts of the region. There are different types of roll mats used as door and window screens as well as room partitions.

Bamboo is a widely available grass which is very handy to use. It grows easily on marginal and wastelands and replenishes itself within 6 months. it is versatile and can be used to build an entire house as well as weave as small a basket. Bamboo plantations conserve soil and water and improve soil;l fertility and local climate. Bug bamboo which is generally called Boans are traditionally not cultivated by the villagers of Uttarakhand owing to the superstitions associated with it being used to carry the dead to the cremation ground,. Village artisans design and weave bamboo baskets and winnows of various sizes and shapes each fulfilling the needs of specific farming activities, right from sowing, harvesting, and collecting to drying and storing. The user often seals some of them with a coat of local cow dung, these baskets are sold further afield through local shopkeepers in market centers. Other itmes such as the baskets. winnows, hand fans are made out of the bamboo products and sold to the local community and the others.

Mutra cane is the raw material for shitalpati and it grows mainly in Cooch Behar. This is kept soaked in water for 24 hours and is then cut into strips to make the pati. Some of the strips are dyed magenta in colour to make patterns. Shitalpati is woven with flat strips in simple checks, twill, zig-zags, diagonals, diamonds, and many other designs, and the motifs woven in the mats are stylised human, animal, or leaf designs mainly in magenta, using the extra weft technique. Cane is also used to make baskets. Traditional shapes like the dhama, dhami, and katha are made. Cane baskets are made with a species of thin cane found mainly in north Bengal. The core material is a whole cane twisted into spirals which curve out gracefully from the base to the rim. The cane is stitched together in simple lines with thin strips of the cane itself. These are very sturdy and are used to carry heavy loads of grain. The cane baskets with a heavy plaited weave are used all over West Bengal to carry head loads of bricks and stones. Bamboo, used mainly for basketry, grows abundantly in West Bengal. Craftspersons sometimes have their own bamboo groves adjoining their huts. The variety of bamboo used for basketry has long fibres and widely-spaced internodes. When the bamboo is solid and thick and has close nodes it is used for construction. In north Bengal a thick but hollow variety is flattened to make the wall panels of village huts. Bamboo containers --- which are smoked to a brown shade, decorated with poker work, with designs burnt in with a red hot point of a steel tool, bound by strips of cane, and fitted with cane handles --- are used to store, carry, and measure oil and milk in many parts of north Bengal. In the hill regions, bamboo lengths are halved, the nodes are removed, and these are used as aqueducts to carry water. The bamboo strips used in basket weaves are flexible and their width determines the appearance of the basket. Paddy bins or containers for storing paddy are usually made of bamboo matting. These are large and have a graceful waist with a cylindrical shape which is the basic structure of the bin. The bamboo which is used for this is slatted, and seasoned by soaking it in a mud bed for three to four weeks.

Jewellery made from forest-based cane and bamboo involves extremely intricate detailing and is the specialty of artisans from the northeastern region of India. It uses the technique of interlacing two or more strands of the material in different ways, akin to the process of coiling or braiding. Assam, Tripura and Arunachal Pradesh are famous for their cane & bamboo ornaments.

Cane and Bamboo ornament making is practiced all across the three states of Arunachal Pradesh, Asaam and Tripura. However, there are always regional variations present

Colloquially called Baans bareilly due to its huge cane and bamboo mandi(market),Bareilly is famous as a production center for cane furniture. Articles such as furniture, dustbins, racks, lamps, baskets, pot holders, sofa sets and center tables are part of the huge repertoire of items produced. Tools used for the crafting process range from saw, kerosene lamp, hammer to knife.

Many centres like Allahabad, Barely, and Varanasi make baskets and other articles from bamboo, cane, and raffia. Each centre has its own style in the use of raffia, locally referred to as mooj. This grass is usually grown on field edges so that it acts as a fence and also keeps stray animals away. The outer stalks of the mooj grass are sun-dried and preserved in tin or wood containers for use. This craft is a part of family tradition and every daughter starts acquiring basket-making skills from an early age. The wide range of bamboo, cane, and raffia products include baskets, trays, wall decorations, and furniture

Cane and bamboo, which since ancient times have provided the raw material for basketry, mats, and other utilitarian items, including furniture, are essentially rural crafts connected with the everyday needs of people. The tall golden white sarkanda grass growing around Delhi and Haryana has made these a centre for the manufacture of chairs and moorahs or stools. Closed baskets, lounge chairs, waste-paper baskets, and trays of various sizes are also made and sold. The long strips of sarkhanda grass are cut and tied in a criss-cross fashion. They are then wrapped with wheat straw to hold them together. This is covered with a cord made out of munj grass or brightly coloured cotton or plastic. The colour binding makes these chairs more attractive.

Basket making is a home based craft across the Himachal The baskets are made by professional basket makers as well as by the women of Pahari households during the winter months. They are sold at the local fairs and weekly markets, at the Dussehra Festival and during the marriage season. Baskets are used to store, carry, work and for other functional purposes. Elaborately woven and strong the baskets are made of bamboo and other locally grown grasses such as the nargal (a thin grass). Load-bearing baskets are made from local wood-stemmed grasses - the toong , a thick grass found in the higher reaches of the mountains that is used for reinforcement, and nargal. Other grasses used are the chupod (a soft grass),phhagad (a hard grass);banana fibres or palm leaves. The techniques utilized in the construction of the basket vary according to the purpose of the basket but are usually combinations of coiling, interlacing and plaiting.

The using of natural fibres for making mats, baskets and other products is one of the oldest crafts practised in Pakistan. For centuries artisans have woven, moulded, twisted and stitched a variety of fibres to provide products for numerous purposes.

The specialities of the furnishing fabrics from Cannanore or Kannur are their compact structure and texture of cloth, unique colour combinations, wide width (90-120 inches) and skilled craftsmanship. The fabrics range from stripes and checks to floral or geometrical designs, with woven borders, manufactured from cotton or art silk or in combinations of both. The handlooms of Cannanore produce a wide variety of home furnishings such as bed linen, bath linen, kitchen linen, cushions and suchlike.

Navalgund a small town in the Dharwar district is where the most colourful dhurries are woven. Earlier it was a weaving centre for woollen carpets but as wool became more expensive there was a switch to cotton dhurrie weaving. The motifs remain the same, and geometrical and floral designs abound. Navalgund dhurries are characterised by unusual patterns and stunning colours. Although these are cotton dhurries, yet the bright and lustrous colours used make them look far from ordinary. The art of dhurrie weaving has been passed down from one generation to the next. Families guard craft techniques even from their own daughters (who do not practise the craft). However, attempts are being made to introduce production on a more efficient and regular basis. A special dhurrie called sutada is made in Bijapur and Dharwar districts of Karnataka. This has simple, horizontal stripes of different colours. In Mulgund and Murgao of Dharwar district, a special dhurrie is made by joining together various nine-inch pieces of coloured cloth. Inspiration for the motifs is derived from wall paintings and wooden miniatures. Special designs are made for festive occasions.

Masulipatnam is an important carpet-weaving centre in Andhra Pradesh. The weaving of Indo-Persian carpets here began with the settling of the Arab community in the area. The vocabulary of carpet-weaving gradually fused with the local language, with the central ground of the carpet being called the khana and the border becoming known as the anchu. The patterns used are named after fruits or flowers like babul, ambarcha, guava, and jampal. The main designs on the carpets are named after the patrons of the carpet-industry: for instance, Ramachandra khani, Reddy khani, and Gopalrao khani. Other common names include Nurjehan, Shah Nawaz, Gulbanthi, Farasi, and Shahnammal. The designs are mainly floral or geometrical and the combination of shades is often a blue and green mixed with soft yellow and pastels. The carpets of Eluru and Warrangal are the pride of Andhra Pradesh. Carpet-weaving at Warangal began when the Mughal army --- which included artists and craftespersons -- moved into the Deccan region. Since the area around Warangal grew abundant cotton and was also known for weaving, thus carpet-weaving began flourishing here without great difficulty. Originally the local short-staple wool was used but now fine carpets are being manufactured by using long-staple wool from Bikaner. Most of the weavers are men; only a few women have been trained in the craft. Here also, the designs are often named after patrons. Mahbub khani, Teerandas khani, Hashim khani, Dilli khani, and Thotti khani are examples of this practice. The designs are again of Indo-Persian origin. Complicated designs are woven and the traditional talim technique is also present. Most often, the background is off-white and the designs are in deep green and orange. Dilli khani has boats (kishti) and floral motifs, and Thotti khani is a design-composition built around flower-pots (thotti means a clay flower pot). In 1885, these carpets, known as Deccan rugs were part of the British Empire Exhibition held at London and received an award for fine workmanship.

Carpet weaving calls for a high degree of skill and dexterity and is generally done by the Monpa women in West Kameng and the tribes of North Siang, district apart form the Tibetan community settled in the area. Carpets are woven in bright colours with predominantly Tibetan motifs such as the dragon or geometric and floral designs, reflecting the Tibetan-Buddhist influence in the area. Wool colours were originally obtained using vegetable and other natural dye sources, although synthetic dyes and chemicals are now commonly used.

Knotted pile carpets produced without using any mechanical contrivance are artistically created by Gujarat's carpet-weavers. The only tools used are a knife for cutting the weft after the knot has been tied, a panja made of iron for beating in the weft and the pile tufts, and a pair of scissors for cutting the pile level. Traditionally, vertical wooden looms are used for weaving.

The kind of carpets made in Kashmir resemble Central Asian styles like bokhara and Turkish makes. Often, a cotton warp is mixed with a woollen weft. Silk carpets are also made. Medallions, horse designs, and hunting and animal scenes are the motifs used. Floral and plant designs in unusual sizes can also be found. Trellis designs, the hallmark of Mughal traditions, are combined with plant motifs. Medallions in many varieties and shapes are found along the borders. In these carpets, repetition does not give rise to monotony. Since carpet-weaving originated in Persia and travelled to Kashmir, the designs are mostly local variations of Persian themes. In addition to the design, the knotting of the carpet is the most important aspect determining durability and value. Kashmiri carpets are always hand-knotted. A carpet is extremely expensive and considered as a lifelong investment. The carpet industry provides employment to a large section of the local population and also earns a fair amount of foreign exchange. The carpets woven in Ladakh are an integral part of the culture there. The community of Buddhists in Ladakh prepare carpets chiefly for personal use. The people in the area have been weaving the carpets from very early times. These are used as the main form of furnishing in a region where temperatures dip to extreme lows. The carpets are used for sitting on during the day and sleeping at night, as well as to seat guests and in ceremonies and feasts. The basic Tibetan style which is 3 inches x 6 inches is known as the khalidal. These carpets are woven by looping knots known as khabdan. The designs woven into the carpets are generally drawn from religious motifs, inspired by the symbols of Mahayana Buddhism.. Barajasta is the technique in carpet-making where the main design is worked out in pile and the background has a plain weave in gold thread which adds a lustrous appearance. Bokhara carpets are made in pure wool and three rows of irregular octagons form the main motif. Other geometrical motifs are used sometimes as are leaf patterns; the motifs at the edges include the 'tree of life', diamonds, herringbone, and latch hooks. The colours used are ivory, red, blue, and green. The background is usually in mahogany, mauve, yellow, dark green, and burnt almond or orange. The skeletal warp of the carpet is stretched tightly on the frame and the weft threads are passed through the talim or design, after which the colour specifications are worked out. Woollen carpets are very well-known in Kashmir and they are called kalin. Shawl weavers here took to carpet weaving as this has a better demand. Talim, a weaver's alphabet in shawl-making, started being used for carpet-weaving. The colour card has the dyed pieces of thread attached to it to indicate the colour combination to be used. The talim is organised in graphical manner, with each square standing for one knot, with the design being built up on this basis. The talim and the shade-card or the rang-ticket as it is called are combined together for the weaving operation. The talim writer may take up to three months to finalise it, depending on the number of knots per square inch. Indian carpets are distinguished by the panalidar back or pronounced ribs running down the back of the carpet. Modern carpets have a smooth back and the quality is not very good.

The main centre is Gwalior where carpet-weaving began in the early part of this century and the designs are traditional.

Traditionally, the northeastern belt weaves hand-knotted woollen carpets with bold colourful designs on upright wooden frame looms. The method of weaving and the motifs and colour schemes are similar in the entire belt. The warp of the carpet is cotton and is mounted on the upper beams while the woven fabric is wound on the lower beam. Knotting is done, with great skill and dexterity, by looping the woollen thread around the warp. The rod used for looping is placed along the warp. When a motif or a new colour is introduced, the ground colour is cut and the new colour thread is inserted by twisting into a single warp thread and looping. The loops are finally cut with a knife and a pile is created. The number of knots per square inch could vary from 40 to 100. The patterns are mainly geometrical, using different colours to build the shapes. Bold floral designs or symbolic Tibetan motifs are also used. The colours are bright and bold and vegetable dyes are used.

The women of the Bhutia community of Sikkim practice what is perhaps the oldest form of carpet-weaving in the world. They traditionally weave hand-knotted woollen carpets with chiefly Tibetan designs on upright wooden frame-loom.

The warp - taan of the carpet is cotton and is mounted on the upper beams while the woven fabric is wound to the lower beam. Knotting is done, with great skill and dexterity, by looping the woollen thread around the warp, and the rod which is used for looping is placed along the warp. When a motif or a new colour is introduced, the ground colour is cut and the new coloured thread is inserted by twisting into a single warp thread and looping. The loops are finally cut with a knife and a pile is created. The number of knots per square inch could vary from 40 to 100. The design is first drawn on the graph paper and later translated in the weaving process.

The method of weaving and the use of decorative motifs and colour schemes are unique to this community. The patterns commonly woven on to the carpets are stylised floral motifs, compositions borrowed from Buddhist iconography, eight Buddhist lucky signs, geometrical designs, and most popularly, Tibetan designs like a dragon holding a ball in his mouth or the two mythical Tibetan birds called the dak and the jira. Tibetan designs have a wide range and each has a significance and name of its own. The overall effect on the carpet is a single, powerful, bold design. Geometrical patterns are created using knots of different colour. Vegetable and natural dyes are still used to obtain the right colours. Besides regular carpets the Bhutia women also weave small bedside carpets and squares called asans to sit on. Their weaving techniques are being extended to dhurrie-weaving and woollen dhurrie-weaving.Woollen pile carpets have played a prominent part in the textile history of Pakistan. At present in Pakistan a wide variety of carpets and floor coverings are being produced.