Votive terracotta figures are found widely in the districts of Bastar, Jhabua, Sarguja, Raigarh, and Mandla. Clay icons are placed on the borders of villages to ward off evil spirits, to appease and propitiate unseen forces, and also to seek their blessings for a trouble-free and happy life. Icons of Matri Devi or the Mother Goddess, known as Mai among tribals, are installed and propitiated to guard villagers from plague, fever, and epidemics. The idols have various names, linked to the name of the village: Khanda Mai, Banjarin Mai, Kankalin Mai, and Chechak Mai. The tribals of Bilaspur have animal and human figures on their roof tiles. The Baigas and Gonds of the Mandla region make figures with sunken eyes and big noses, with their head covered with animal hairs. These are linked in some form with witchcraft and evil spirits and are placed in fields or on roof tops as protection. Sacred spaces under trees also have votive terracotta offerings. A wooden pillar intricately carved with figures of gods and animals is installed in the central courtyard of temples, known as the devgudi. Clay images of gods and goddesses are also installed in the temples. Propitiation of the deities is done with votive terracotta offerings. Horses are a common form of terracotta figurines. The terracotta elephants of Chindwara are depicted with two riders sitting on a howdah. Howdah elephants are crafted in Bastar, Mandla, and Betul. They are sometimes used as the sinhasan or seat of the Mother Goddess. Betul specialises in animal figures. The mud walls of houses are adorned with clay murals, clay relief, or carvings, usually done by women. Clay is mixed with paddy husk and cow dung in this process, and the motifs are include traditional chauk or square motifs and animal figures on the internal and external walls of the houses. This relief work is bare and unpainted. In Rewa and Shahdol, life-size figures of gods and goddesses like Ganesha, Hanuman, Shiva, and Kali, depicted on the interior walls of the houses, give them a temple-like aura. The facial features are finely carved and embellished with fine lines. Tribal terracotta masks form a part of all community celebrations and are very popular in the regions of Bastar, Sarguja, Mandla, and Betul. The Chher Chhera festival is celebrated with young men and women wearing masks dancing and singing. Clay masks are made out of clay pots or matkas with holes for eyes and with clay noses stuck on them. Masks are coloured red and are used in folk plays and dances. Matkas turned upside down with bold and grotesque features are seen fixed on bamboo poles in fields acting as scarecrows. The tribal groups of Sahariya, Gond, Baiga, and Pardhan make attractive grain storage bins embellished with carved animal and human figures. Lamps or diyas are also common terracotta products. The famous chidiya diya of Sarguja is a complicated wheel-thrown oil lamp and works on the siphon principle. The bird's belly is detachable and has a tube-like opening by which it is filled with oil. Since it is kept lit at the devgudi of the Mother Goddess, it is known as Mata Diya or Mother Lamp.

A variety of earthen objects such as pitchers, flower vases, pots, cut-work lamps, Matka-water pot, Surahi- the narrow necked pot, Gamla- flower pots , lanterns, cutwork lamps, Handi-cooking utensil, Parat-larger platters, gulaks, chillums, handis, musical instruments Diya-oil lamps, Aarti lamps used in rituals, idols and figures of gods and goddesses, large garden pots, patterned tiles, roof tiles, urlis, etcall made of light red clay which boasts a cooling effect can be found in abundance.

A large number of the potters in Delhi have migrated from the neighboring states of Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh Rajasthan. They are located in Govindpuri and Hauz Rani: Kumbhar Basti. A number have settled in the Prajapati Colony in Uttam Nagar that was set up in the 1970’s to house the potters. As most of the potters had names connected with their caste occupation the colony was called Prajapati. Currently over 400 families practicing this craft in the colony and provide their products across Delhi and NCR.

The methods adopted by the potters are similar to those employed in the pottery tradition(s) of their ancestral place. Black, red, and yellow clay in the form of small pieces is obtained from Rajasthan and Delhi. This is mixed and dried, after which water is added to it. The resulting mixture of wet clay is filtered through a fine sieve to remove pebbles. After the clay has been kneaded into homogenous flexible dough, the prepared clay is made into a variety of artifacts using either the throwing technique. Coiling technique is used in making large products that are too large to be thrown on the wheel and to make those with shapes that cannot be turned on the wheel. After giving shape to the item and drying it in the shade, it is baked in the kiln. The potters specialize in making particular products and have specialize in what they do.

Their tools are rudimentary and include the the Kumbhar chaak or potter's wheel, the electric wheel, the Khuriya or turning tool, the Mogri wooden mallet , Sua or incising needle, the Thapi wooden beater, Thapa – the large beater, Maniya or die and the Katni carving tool.

Goa earthenware, with its deep, rich, red surface has a charm and style of its own. The North Goa districts of Bicholim and Calangute are well known for its red clay pottery traditionally done by the Kumbhar community who now have added stoneware products to their repertoire. Making both utilitarian products for cooking and storing liquids - such as pots, bowls, plates and vases, they also craft items like lamps, idols, sculptures, planters, large figurines and masks for sale. The red clay is obtained from the fields in Bicholim then kept in water for two days and sieved through a net till a fine homogenous mixture is obtained. It is left to dry for 10 days till it is ready for kneading. The processes used include throwing, coiling, beading, pinching, sculpting and manipulating the clay to form the object. The Kumbhar also use the processes of moulds, clay slip as joinery and slab casting when needed. Local kilns are used for firing. The terracotta objects are fired in a kiln and cooled for a day. The products are sold at Mapusa and in weekly market in Panaji and Madgaon.

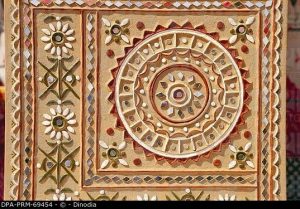

Kutch and Saurashtra in Gujarat are noted for their beautiful pottery. The ware is white, with delicate designs on it. Bhuj in Kutch has a colony of potters producing clay utensils, tea kettles, bowls and pots for water, miniature toys, grinding stones, furnaces, and griddles. Festival objects like toy elephants, bullocks, and horses are also made by hand. This region is also noted for large grain containers. The pottery has a distinctive pale creamy colour. Relief work is done on it with mirrors and motifs. In Saurashtra, votive terracottas of horses, elephants with riders, calves, and goddesses, as well as imaginative versions of the deity Ganesha are done by hand. The handmade figures are moulded by women, and the wheel is by manned by men. This region is noted for its gopichandan --- clay which is the colour of sandal wood --- from which buff coloured pottery is made. Clay utensils with a lac coating are crafted by the tribals of the Chota Udepur region. Botad village in Bhavnagar is noted for clay whistles, clay bells, and clay buttons . Gujarat has a unique tradition of votive terracotta, that follows from the Indus family heritage. Figurines of animals and humans are made from clay and coated with lime. They are then painted upon and are often placed in shrines and sacred groves. The raw material of these products is the mati- red clay, also called terracotta. After the pounding and preparation of the clay, it is moulded by the use of a charkha (spinning wheel). After the moulding, the clay is hand modelled with unique and intricate designs that are very akin to the hand embroidery done on the textiles.

The kumbhar potters of Haryana are known for their slim-necked pitchers called surahi. These water pots serve to keep the water cool. The surahis of Jhajjar and Chawani Mohalla are especially famous as the water contained in these surahis acquires a special taste due to the quality of the clay available in these low lying area. Made from a combination of thrown and moulded parts the entire families participate in the craft process beginning with the preparation of the clay by the women and the youth. The men sit on the wheel to create the wheel-thrown surahi necks. For the round base, the clay is rolled and stretched over an upturned pot and then pressed into semi-circular terracotta dies that are engraved with patterns. After these semi-circular segments are half dry they are joined together with wet clay and left to dry in the shade. At this time the clay shrinks, leaving the surface of the die. Then the women attach the spout, neck and handles. The surahis are dipped in a slip made of barmi and sunaihri, the red and yellow clay, dried again and fired in mud kilns. Besides the surahi the potters of Haryana produce a large variety of terracotta products such as other water pots that are used not only to cool water but also used as ritual vessels for Hindu rites in kuan puja as well as during birth and death ceremonies, oil lamps/ diya, Grains storage pots, Flower pots, piggy-banks and tea cups/ kulhars, bowls of all sizes and use, musical instruments, clay toys, human and animal figures, plaques, medallions, and wall hangings. Two-toned vases, decorative pitchers, and lamp bases with shades of black and terracotta colors are popular. While there are potters in almost every village the potters of Jhajhar Bahadurgarh and Faridabad are the most well known

The tradition of clay and terracotta in Bihar dates back to the Mauryan period when hundreds of male and female figurines and animal figures --- horses, elephants, birds, and reptiles --- were made of clay and baked. This tradition continued down to the Mughal period. Each village, district, and region has its own style of pottery and of decoration. The some rituals continue to be practised in their original form. The making of toys and images was --- and is --- closely connected with seasonal festivals and other religious ceremonies. In the past, clay village gods or gram devtas could be seen outside each village, guarding the inhabitants against bad luck, illness, and the wrath of nature. Clay elephants, signifying marriages, could be seen on the roofs of houses. These figures were not merely religious but also served as toys for children and decorations in bed chambers. Sometimes they were hand-modelled, while at other times they were moulded. Today, the potter's art in Bihar is confined to medium and coarse red wares and the making of dolls and toys on festivals and special occasions.

Pottery is an age-old Indian tradition and the demand for it has never dwindled. In south India terracotta pottery has attained a high level of perfection. The potter is a member of almost every village community. The principal tools employed by this craft are the wheel, a convex stone, and series of flat mallets for tapping vessels. Red clay is used most commonly in manufacturing flower pots, images of gods and goddesses, and animal shapes. Sometimes the potters used reduction firing to give the pots an uneven black colour. Another interesting and less well-known use of the potter's wheel is the production of country roofing tiles which are molded in the form of cylinders and then split in half with a knife. Principal pottery cluster in Karnataka is in Kodagu district. They make small handmade terracotta toys and they also make bricks which are sold in local towns nearby.

The tribal groups found in these areas are Bhils, Bhilalas, Barelas, Patalias, Nayaks, and Mankas. Jhabua is known for votive horse figures. Horse figures, solid or hollow, are painted ochre and white. The white surface sometimes has red dots. Figures are crafted by making cylinders and then joining them together. Folk idols of the goddess Lakshmi are in great demand during diwali time. Bhils and Bhilalas of Jhabua make clay temples called dhabas, ranging in height from 1 cm to 1 m. These are offered with terracotta horses at the village shrine. The top of the dhabas are decorated with a kalash or a circular pot-like motif. The dhaba has a small door through which a diya or lamp can be placed inside. Horse figures are offered to the deities two days before Diwali (on dhanteras and kali choudas or diwali) and between the months of April and June ( chaitra and vaishakh). A community meal is organized. Clay horses are also offered to ward off evil spirits from the fields and to seek blessings for a bumper crop. Terracotta from Jhabua has crude, solid, and plain figures. Hollow terracotta figures are big and stylised. Life-size figures of sargujas are made. The figures are painted with white chalk and ochre. Mandla terracottas show tantric influences and figures from Betul have form and variety. During Diwali, terracotta idols of the goddess Mahalakshmi, and of gaulang or elephants and horses with riders are molded as solid figures, washed with lime and painted brightly. The region also specializes in making terracotta heads of Gangaur, a local form of Goddess Parvati. These heads are fixed on poles and adorned with clothes. Cylindrical figures of Gangaur idols are made and installed in houses during the month of chaitra. Adla pakshi or love birds is a popular figure in this region; the heads of the love bird are attached to a common cylindrical body with a pair of wings and are a symbol of inseparable lovers. The toys are handmade and are either hollow or solid. They are made usually by women. Animal figures like horses, elephants, dogs, lions, birds, deer, and bulls fixed on wheels are very popular with children. The sizes of the figures are usually small. Solid figures have a lot of variety and are more popular than hollow ones. Artisans also make hollow bird whistles. Some utility products include; Kuldi- pot for water, Chhalki- vessel for making curd, Bhutia- for storing toddy, Warya- for tapping male toddy tree, Faalna- for tapping female toddy tree and Wahaadi-small ritual vessel with a spout.

A number of pottery units in the Garo Hills are engaged in the production of clay utensils; these occasionally produce toys and dolls as well, particularly at the time of various festivals and religious functions in the area.

Clay figures are made all over Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry. Traditionally each village is guarded at its entrance by an enormous terracotta horse, which is the horse of Ayyanaar, a religious figure, the gramdevta of the village and its protector against all evils. Aiyyanar has an enormous moustache, big teeth and wide open eyes that keep constant vigil. Ayyanaar stands at the entrance surrounded by his horses and commanders or veerans. Ayyanaar figures, which include the horses in the army, range in height from less than a metre to over 6 metres. They are some of the largest terracotta figures to be sculpted and are painstakingly made by mixing the moist clay with straw and sand for a proper consistency. For the horse, four clay cylinders are rolled out with a piece of wood, for the legs, after which the body is built up gradually. The accessories, such as bells, mirrors, grotesque faces (kirthimukha) and crocodiles (makaras), are made separately as is the head. The parts are joined together on the auspicious tenth day, when the figure of Ayyanaar seated on the horse is given its features. This is then baked in a rustic kiln of straw and verati or dried cow-dung which is then covered with mud. Parts of the larger figures have to be fired separately, joined together and fired again. The faces are sometimes painted red to denote anger and the neck blue to denote calm. The rest of the body and decorations are also painted in bright colours. The oldest Ayyanaars and horses are found in Salem district. Salem and Pudukottai districts make the most large terracotta horses; the smaller figures, human, divine and animal, are made all over the state. Given the time taken by the firing process, moulds are becoming popular to hasten the process. Ayyanaar figures are found in the village sanctuaries of Chettampatti and Nallur (Tiruchirapalli district), Tirripuyanam (Madurai district), and Vadugapalayam (Coimbatore district). Most of the other village deities are also made of terracotta. The temples found in the village are usually for the mother goddess or ammankovil along with a temple to the deity Ganesha or Pillaiyaar. Another important terracotta shrine is the naaga or serpent shrine, situated under a pipal tree near an anthill. It is made of clay with an intertwined body and is worshipped for its power of protection and rejuvenation. On Vinayaka Chathurthi clay Ganeshas are made and sold everywhere. These range in height from a few centimetres to a metre and they are glazed, painted, baked or often unbaked. The models are immersed in wells after the festival, and the unbaked form is preferred as it crumbles easily. Other products crafted include water drawing and storing pots and cooking vessels. During the harvest festival of Pongal old pots in the house are replaced by new cooking pots, vessels for storing grain and a new container for the auspicious tulasi/holy basil plant. The pots symbolise continuity of life, creation, destruction and rebirth. In Tamil Nadu, potters are known as kuyavar, kulalaar or velar and they trace their origin to Vishwakarma, the divine craftsman himself.

Clay figures are made all over Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry. Traditionally each village is guarded at its entrance by an enormous terracotta horse, which is the horse of Ayyanaar, a religious figure, the gramdevta of the village and its protector against all evils. Aiyyanar has an enormous moustache, big teeth and wide open eyes that keep constant vigil. Ayyanaar stands at the entrance surrounded by his horses and commanders or veerans. Ayyanaar figures, which include the horses in the army, range in height from less than a metre to over 6 metres. They are some of the largest terracotta figures to be sculpted and are painstakingly made by mixing the moist clay with straw and sand for a proper consistency. For the horse, four clay cylinders are rolled out with a piece of wood, for the legs, after which the body is built up gradually. The accessories, such as bells, mirrors, grotesque faces (kirthimukha) and crocodiles (makaras), are made separately as is the head. The parts are joined together on the auspicious tenth day, when the figure of Ayyanaar seated on the horse is given its features. This is then baked in a rustic kiln of straw and verati or dried cow-dung which is then covered with mud. Parts of the larger figures have to be fired separately, joined together and fired again. The faces are sometimes painted red to denote anger and the neck blue to denote calm. The rest of the body and decorations are also painted in bright colours. The oldest Ayyanaars and horses are found in Salem district. Salem and Pudukottai districts make the most large terracotta horses; the smaller figures, human, divine and animal, are made all over the state. Given the time taken by the firing process, moulds are becoming popular to hasten the process. Ayyanaar figures are found in the village sanctuaries of Chettampatti and Nallur (Tiruchirapalli district), Tirripuyanam (Madurai district), and Vadugapalayam (Coimbatore district). Most of the other village deities are also made of terracotta. The temples found in the village are usually for the mother goddess or ammankovil along with a temple to the deity Ganesha or Pillaiyaar. Another important terracotta shrine is the naaga or serpent shrine, situated under a pipal tree near an anthill. It is made of clay with an intertwined body and is worshipped for its power of protection and rejuvenation. On Vinayaka Chathurthi clay Ganeshas are made and sold everywhere. These range in height from a few centimetres to a metre and they are glazed, painted, baked or often unbaked. The models are immersed in wells after the festival, and the unbaked form is preferred as it crumbles easily. Other products crafted include water drawing and storing pots and cooking vessels. During the harvest festival of Pongal old pots in the house are replaced by new cooking pots, vessels for storing grain and a new container for the auspicious tulasi/holy basil plant. The pots symbolise continuity of life, creation, destruction and rebirth. In Tamil Nadu, potters are known as kuyavar, kulalaar or velar and they trace their origin to Vishwakarma, the divine craftsman himself.

Melaghar and Palpada village of West Tripura district are known for their special pressed clay work. About fifty families in these villages are making and marketing these painted clay work. Traditionally wheel based pots and utensils and handcrafted by the villagers who have diversified into other objects of skill and dexterity. Potters now also make small items of utility like oil lamp, flower vases, decorative wall tiles and pressed functional roofing tiles. Statues of popular gods and goddesses are a great attraction in fairs and festivals. The technique is to use a process of press forming inside moulds made of plaster-of-Paris that are cast over a well crafted original piece. Another significant skill of the potters of Tripura is to make dies and moulds. Clay baked die are popularly used in the preparation of milk sweet called sandesh .

Among the clay products of Uttar Pradesh, the wares of the potters of Gorakpur are well known. They make animal figures like horses and elephants with hand-appliquéd ornamentation. Figures of goddesses converted into lamps, mother and child motifs, and other ritual objects are all crafted here by hand. The potters in Uttar Pradesh make both utilitarian as well as decorative ware from clay. The throwing is done by only men as women getting involved in this stage of the process is considered inauspicious whereas women carry out the remaining stages of this craft. The Hindu potters are called Prajapati and the Muslim potters are called Kasgars. Both have only one key factor that differentiates the wares crafted by them. Since Hindus do not use the ware twice, the decorative element is done away with while the opposite happens in the pottery produced by the Kasgars where the finishing and ornamentation is specifically taken care of. Products such as tea glasses/kulhars, joined bowl and pot/malwa, cup with spout/tutuhi, curd bowl/nadia, troughs/hauda, shallow bowl/piyalia, container/parva, karva chauth/larva, pipes/chilum, pitchers/surahi, shallow plate/rakabi, lamp/diya, wall plaques and bells. Tools such as wheel/chak, slicer/lesure and moulds are used in the crafting process.

Bengal offers some of the finest examples of terracotta panels in the temples of Murshidabad, Birbhum, Jessore, Bansberia (Hooghly), and Digha. The style is folk and the designs are expressive with a good amount of relief work, and a play of light and shadow. The traditional potters of West Bengal belong to a caste known as kumbhakars or pot- makers. The exceptions are the Muslim potters at Murshidabad. The clay is sourced from river beds, ponds, pits, and ditches. Clay from two to three sources is mixed together to get a better clay body. The fuel used to fire low-temperature pottery is twigs, dry branches, leaves, and locally collected firewood. Open pit kilns are used which are efficient and inexpensive and can afford a temperature of 700 to 800 degrees celsius. The pots are arranged in layers with leaves, twigs, or cow dung cakes in between, which is then covered with rice straw and loamy soil. Firing takes four to five hours. The other kind of kiln used is shaped like a local bamboo winnowing tray, semi-circular at one end and extending at the diameter in the form of a flat, shallow slope with a rounded opposite side. This is deeper than a round kiln. These kilns are larger and are used for firing larger pieces at temperatures higher than 800 degrees celsius. Other than the kiln and the wheel, the tools used by the potters include hand tools made of bamboo, wood and iron. The women in the kumbhkar families do not throw the pots on the wheel; they make beaten bottoms of round pots and solid clay toys and dolls. This is because only the necks and upper halves of round bottomed pots are made on the wheel. Women finish, decorate, and paint the pots. Figurines of the goddesses Shakti, Lakshmi, and Saraswati, and the abstract figure of Lord Jagannath, Lord of the Universe, are made and worshipped; these are either solid or made using burnt clay moulds. Large images of goddess like Durga and Lakshmi, as well as of other gods, are modelled on straw armatures and left un-burnt. The womenfolk of Shankhakars in Bankura district make primitively formed ritual figurines in burnt clay. Pottery centers in Calcutta and the Sunderbans specialize in storage pots --- these are as high as 2 metres, with a diameter of 1 meter. The potters of Bengal make a variety of other products also. Manasha ghat is a ceremonial pot symbolising the folk goddess, Manasha, queen of the snakes and Manasha chali, intricately decorated, also represents Goddess Manasha. In the manasha chali, individual component are thrown on the wheel in large quantities, and are then assembled. Smaller figures are modelled by hand. Figurines used for wish fulfillment and recovery from serious illness include horses, elephants, tigers, monkeys, and other animals, real and imaginary. Semi-abstract terracotta human heads symbolise forest gods. They are made by throwing parts on the wheel; the parts are assembled later. The ritual horses of Bankura, Purulia, Midnapore, Maldah, and Paschim Dinajpur are well known. Glazed pottery ware is restricted in West Bengal to semi-porcelain tea cups and saucers. Otherwise it is the un-glazed pottery ware that predominates. Terracotta is important in the rural areas of West Bengal, notwithstanding the availability of substitutes, mainly because of the demand for clay water pitchers (which keep the water very cool), for mangers or clay feeding bins for the cattle, and for clay pots to make parboiled rice. Ceremonial and ritual items are still made of clay. Items like tea mugs, plates, tumblers, and bowls of different sizes, beautifully shaped clay ware dahi (yoghurt) pots, and many other items that are thrown away after use are always in demand. Kumbhkar potters and sutradhars or carpenter-carvers combine forces for crafting the terracotta decorations in temples. Most temples in West Bengal were decorated with terracotta plaques in several unique styles. Kumbhkars prepared semi-hard blocks of plastic clay on which the sutradhars carved with small and thin chisels. Potters dried and fired these. Sutradhars carved repetitive designs in reverse on wood or semi-hard clay blocks (burnt by potters after drying). These were used as press moulds by less skilled helpers and the finishing in a semi-hard condition was done by the sutradhars in a carving style that matched the other carved panels used. Terracotta decorations were used dominantly on the temple front. These temples are found in Bankura, Murshidabad, Hooghly, and Nadia districts. The terracotta figures of the 16th and 17th centuries are powerful and pulsating with rhythmic vitality. Faces are in profile and limbs are beautifully oriented in the overall design. The patterns of decoration in most of the temples were the same. The lower area of the walls depicted temporal themes. Above that, the designs included scenes from the lives of Lord Krishna and Lord Rama. The themes depicted above the arch were scenes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, including scenes of war. The ten incarnations or avataras of Lord Vishnu would be depicted in smaller panels on either side, illustrating a single episode relating to them. Large panels depicting devotees of Radha and Lord Krishna dancing and singing to the rhythm of khol, drums and cymbals can be seen. Other themes ---- the lives of saints and savants with scenes from contemporary social life --- were found on small plaques.

Located in the northern most region of Gujarat, Deesa is sited on the banks of the river Banas which in the past provided the mineral rich waters for the textiles colors to blossom in its wash. The local populace provided the clientele for the full length drawstring gathered Ghaghara skirts, the head mantle odhnis, the saris and the pagdi head turbans. Skilled printers juggled their choice of the cotton textile base to suit the intended user while simultaneously choosing and positioning the placement of the motifs according to the client's requirements. The layout for the sari took into consideration the end piece, the borders and the patterning in the field, the ghghras, a minimum 10 meter cotton length, requiring borders on three sides; the head mantle with its four sided border, a central motif and overall patterning, while the pagdi required its own specific orientation. Motifs and colors specific to caste and tribe were printed to suit the Patels, Bhils, Rabari, Mali and others, identifying its wearer's affiliations, status and social standing. The 'Widow's sari', for instance, block printed specifically for the Patel community with small, usually geometric, sparsely printed motifs in black on a white background, clearly identifies the marital status of the wearer. Deep claret, iron black, white and indigo-blue supplemented with turmeric yellow and green form the traditional color palette at Deesa. Natural dyes such as pomegranate and turmeric are also used to achieve a wider range of colors, with synthetic dyes gaining popularity for their ease of use. While the block printers in Deesa are known for their mud-resist process of block printing, they are adept at wax-resist printing and discharge printing too, with three families continuing to practice this art at present.

Many small trucks which are transporting them, in various shapes, sizes and colors, to all parts of Maharashtra, and even to places as far as half way around the world to the US. Pen, located about 80 kms, Southeast of Mumbai, in Raigad district is the center of production for the clay idols of the Hindu God of Luck and Prosperity, Ganesha. Over 30,000 of the residents of this Pen are involved in the value chain of raw material procurement, creation of idols to transportation to places in Maharashtra and even overseas. This process started in 1970 with improved road transport from Pen to Mumbai and Pune giving Pen a strategic locational advantage and the entrepreneurial spirit of the place turned this local art form into a hub of idol production. While most of the raw material is sourced out of Pen with the clay from Gujarat, the colors are now available in the local markets, sourced by the traders to suit changing needs and trends. While casts of forms and shapes are available, the process of coloring and making unique is a highly developed art here.

Clay relief work of Kutch can be seen in the meticulous execution of circular huts or bhunga in the region. Composed of clay or bamboo chips plastered with a mixture of clay and dung called lipan, these huts have wooden based thatched roofs. Other structures such as large storage granaries called Kotholo, large storage for valuables and clothes called Sanjiro, cylindrical grain storage called Kothi, seat for babies called dhadablo, clay stand called utroni, portable hearth called chula, clay platforms called paniyara, platforms on which the storage bins are placed called pedlo etc are constructed. Decoration elements can be seen on walls, alcoves, plinths, shelves and windows etc. the process is carried out using brushes made from branches of the baval tree.

The toys of West Bengal have traditional folk forms. The scenes and figures depicted are largely rural, depicting different types of peasant figures, huts, temples, carts, and domestic animals that are part of the countryside. The main centres are Jainagar and Rajgarh. The clay toys made in Shantiniketan are very realistic, while the toys from Krishnanagar in Nadia district have fine shapes and chiselled features. Figures of religious deities are also crafted. The traditional toys are all moulded by hand. The work is done with care and finesse and with a great deal of attention to detailing. Toys are painted in bright colours after firing. A coat of gum extracted from boiled tamarind seeds gives a shine and a smooth finish to the toys. This is a hereditary craft, and it usually takes 10 to 15 years to master the skill.

Lucknow is famous for its clay toys which are crafted intricately by the Kumbhars who belong to the Prajapati community. The practice of making these toys began and drew inspiration from the British in the first half of the last century to cater to their interest in collecting vignettes of Indian life. Made and sold in sets these are of two kinds- figurines and fruits. The former are made using cast fro the body and hand-rolled clay for hands and legs while the latter are made using only cast. Products like band sets, serving sets, raja-rani sets, brides, sadhus, erotic toys, and idols etc. are crafted by the artisans. Tools such as terracotta moulds, brushes and wire are used for the process.