Cotton Zari Saris of Andhra Pradesh,

Simple and elegant cotton saris, either with broad borders on both sides or with a single decorative, heavily patterned pallu are woven in Andhra Pradesh. The distinguishing mark is the korvai where the weft threads do not enter the borders. Single-border saris require two shuttles and double-border saris require three shuttles. Country jacquard is used for designs on the borders. Gadwal and Kothakota weave fine cotton saris with rich gold borders and heavy panel-like pallus. Cotton saris with richly woven pallus and borders in gold with opulent designs are also made in places like Siddhipet and Armoor. Upada in Andhra Pradesh is famous for the jamdani technique. The saris are usually in cotton, silk, and a mixture of cotton and silk and the motifs woven are simple and traditional. These white and gold saris are particularly dramatic

Simple and elegant cotton saris, either with broad borders on both sides or with a single decorative, heavily patterned pallu are woven in Andhra Pradesh. The distinguishing mark is the korvai where the weft threads do not enter the borders. Single-border saris require two shuttles and double-border saris require three shuttles. Country jacquard is used for designs on the borders. Gadwal and Kothakota weave fine cotton saris with rich gold borders and heavy panel-like pallus. Cotton saris with richly woven pallus and borders in gold with opulent designs are also made in places like Siddhipet and Armoor. Upada in Andhra Pradesh is famous for the jamdani technique. The saris are usually in cotton, silk, and a mixture of cotton and silk and the motifs woven are simple and traditional. These white and gold saris are particularly dramatic

Craft in Architecture,

One particular aspect of the Newari genius stands out against the Katmandu skyline: architecture. The pagoda-style temple, so characteristic of the Valley, may have been the prototype for pagodas throughout eastern Asia, each country modifying the original Newari idea. Arniko, the most famous of early Nepalese architects, was called to Kublai Khan's court in Peking where, in the late thirteenth century, he became the Imperial Minister for Building and Arts, and is best known for the White Dagoba in Peking's Central Park. The majority of traditional buildings in an around the Kathmandu Valley follow a common architectural style - houses, monasteries, palaces and temples are all constructed in much the same way, using the same materials: wood with bricks, tiles, clay mortar and stone and metal. Although most of the art and architecture of Nepal has been derived from Indian forms, the architectural canon of the Newars is highly distinctive. Multidirectional shrines under sloping roofs do have Indian precedents, but in Nepal this form springs up fully developed, and its history and origins are obscure. This Newar 'style' is distinguished by the 'storeyed', 'multi-staged' or 'tiered' Newar temples and the numerous single-tiered temples that exist. The ancient temples and palaces of Nepal, especially those of the Kathmandu Valley, show exquisite workmanship and architectural designs of the ancient builders of Nepal. Many of these, built of entirely indigenous materials, have withstood the ravages of time and nature. Although the skills used to build them have lain dormant in the centuries since then, there is no doubt that these skills are still present. When the Hanuman Dhoka palace in Kathmandu and the Tachupal Tole buildings in Bhaktapur were restored in 1970s the work was performed by purely traditional means and with craft work every bit as good as in the past. More recently, the Chyasilin Mandapa in Bhaktapur, completely destroyed in the great earthquake of 1934, was totally rebuilt in 1989-90, again using traditional skills.

One particular aspect of the Newari genius stands out against the Katmandu skyline: architecture. The pagoda-style temple, so characteristic of the Valley, may have been the prototype for pagodas throughout eastern Asia, each country modifying the original Newari idea. Arniko, the most famous of early Nepalese architects, was called to Kublai Khan's court in Peking where, in the late thirteenth century, he became the Imperial Minister for Building and Arts, and is best known for the White Dagoba in Peking's Central Park. The majority of traditional buildings in an around the Kathmandu Valley follow a common architectural style - houses, monasteries, palaces and temples are all constructed in much the same way, using the same materials: wood with bricks, tiles, clay mortar and stone and metal. Although most of the art and architecture of Nepal has been derived from Indian forms, the architectural canon of the Newars is highly distinctive. Multidirectional shrines under sloping roofs do have Indian precedents, but in Nepal this form springs up fully developed, and its history and origins are obscure. This Newar 'style' is distinguished by the 'storeyed', 'multi-staged' or 'tiered' Newar temples and the numerous single-tiered temples that exist. The ancient temples and palaces of Nepal, especially those of the Kathmandu Valley, show exquisite workmanship and architectural designs of the ancient builders of Nepal. Many of these, built of entirely indigenous materials, have withstood the ravages of time and nature. Although the skills used to build them have lain dormant in the centuries since then, there is no doubt that these skills are still present. When the Hanuman Dhoka palace in Kathmandu and the Tachupal Tole buildings in Bhaktapur were restored in 1970s the work was performed by purely traditional means and with craft work every bit as good as in the past. More recently, the Chyasilin Mandapa in Bhaktapur, completely destroyed in the great earthquake of 1934, was totally rebuilt in 1989-90, again using traditional skills.

Craft in Architecture, Clay and Terracotta

Visitors to the Kathmandu Valley will be likely to visit the exquisite terracotta shrine of the Maha Buddha in Lalitpur. It is believed that this shrine was built by the famed artist Abhaya Raj Sakya during the reign of Amar Malla, King of Lalitpur. The various forms of clay used in shaping the different images of the deities as well as the method of firing these images are said to have been recorded in a Vamshabali, a manuscript that is missing. Recent excavations carried out at Lumbini, Devadaha, and Tilaura Kot (all in the terai region of Nepal) have brought to light specimens of pottery (terracotta) of remarkable artistic workmanship, supposed to belong to the first and second centuries BC. Decorated bricks found at Taulihawa are considered to be as ancient. Temples, chaityas, and idols made of terracotta belonging to the Malla period display a remarkable degree of skill in the art of making terracotta bricks - the Nepal sambat, erected in the year 686, shows the exquisite terracotta workmanship of the Nepalese artisans. A lattice window and triumvirate done in terracotta in the typical Nepalese style at Chokhacheen (Bhaktapur) are supposed to be 250 years old. A big lamp-stand of clay - supposed to have been made in the year 865 N.S. during the reign of the Malla King, Rajya Prakash Mall - is exhibited every year on the full moon day of the month of kartik.

Visitors to the Kathmandu Valley will be likely to visit the exquisite terracotta shrine of the Maha Buddha in Lalitpur. It is believed that this shrine was built by the famed artist Abhaya Raj Sakya during the reign of Amar Malla, King of Lalitpur. The various forms of clay used in shaping the different images of the deities as well as the method of firing these images are said to have been recorded in a Vamshabali, a manuscript that is missing. Recent excavations carried out at Lumbini, Devadaha, and Tilaura Kot (all in the terai region of Nepal) have brought to light specimens of pottery (terracotta) of remarkable artistic workmanship, supposed to belong to the first and second centuries BC. Decorated bricks found at Taulihawa are considered to be as ancient. Temples, chaityas, and idols made of terracotta belonging to the Malla period display a remarkable degree of skill in the art of making terracotta bricks - the Nepal sambat, erected in the year 686, shows the exquisite terracotta workmanship of the Nepalese artisans. A lattice window and triumvirate done in terracotta in the typical Nepalese style at Chokhacheen (Bhaktapur) are supposed to be 250 years old. A big lamp-stand of clay - supposed to have been made in the year 865 N.S. during the reign of the Malla King, Rajya Prakash Mall - is exhibited every year on the full moon day of the month of kartik.

Craft in Architecture, Jhingati - Terracotta Roof Tiles

The oldest type of roofing tile in the Kathmandu Valley is the jhingati, a flat and thick rectangular piece. Jhingatis can still be found on roofs of temples and old buildings. Their durability and strength bear testimony to the quality of workmanship of the artisans. These roofing tiles are now of an average size of 7" X 3.5" X 0.5"; the earlier tiles were smaller in size.

The oldest type of roofing tile in the Kathmandu Valley is the jhingati, a flat and thick rectangular piece. Jhingatis can still be found on roofs of temples and old buildings. Their durability and strength bear testimony to the quality of workmanship of the artisans. These roofing tiles are now of an average size of 7" X 3.5" X 0.5"; the earlier tiles were smaller in size.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

The process followed in making the jhingati tile is similar to that used in making terracotta bricks.

Carefully chosen clay is kneaded properly with water. The potter uses a rectangular wooden mould that is similar to the brick mould, but is without a base. The wooden mould is placed on the ground, and on one side is fixed a round wooden stick that fits the inside length of the mould, is fixed. The potter throws a roll of the prepared clay into the mould; the excess clay is cut off with a knife. Another wooden mould is placed over the first mould; the potter beats on the upper mould with a wooden hammer. The upper mould is removed, and the lower mould gently inverted over the ground. The potter dips his fingers in water and presses them on one side of the tile, so as to make a slight depression; the tile is then detached and removed. It is placed on the ground for drying.

Besides the traditional jhingatis, another kind of large tile - heat-resistant - are traditionally made in the dimension 21" X 7.5" X 1.5". The process followed is similar to the method of making jhingati tiles though these larger tiles are fired. Made of clay and sand - mixed and kneaded thoroughly before being placed into the mould - these tiles, when de-moulded, are dried and placed in piles and kept ready for firing. They are then given a wash with a solution of lancha clay (a ferrogenous clay with a high percentage of iron oxide), on their upper side. This coating makes the tiles red after firing. In this way 400-500 tiles can be made in 7-8 hours. The tiles are fired in the same way as terracotta bricks. Sometimes, the tiles are placed along with the bricks for firing.

Craft in Architecture, Khapada - Roofing Tiles

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE Using the Wheel: On the wheel, the potter first makes a hollow cylinder of clay with the necessary thickness. The cylinder is then detached from the wheel (and another one is made in the same way). The cylinders thus made are scratched vertically at the opposite ends when they are partially dried. As the hollow cylinders dry and harden the potter breaks them into two halves - the centres of the cylinders are hit with a wooden tool. The separated khapada tiles, after drying, are piled up and fired by using straw as fuel. Using a Wooden Mould: When a wooden mould is used, it is in a semi-cylindrical shape. The mould is placed on the ground. The potter covers the mould with a layer of clay and beats the layer till it becomes uniformly thick all over. It is then detached from the mould and dried. The tiles produced by pressing the clay over the moulds are considered more durable and strong than the tiles made on the potter's wheel, which are light, thin, and brittle. Such tiles are liable to be blown away during strong winds; however, as they are cheaper they are still in use.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE Using the Wheel: On the wheel, the potter first makes a hollow cylinder of clay with the necessary thickness. The cylinder is then detached from the wheel (and another one is made in the same way). The cylinders thus made are scratched vertically at the opposite ends when they are partially dried. As the hollow cylinders dry and harden the potter breaks them into two halves - the centres of the cylinders are hit with a wooden tool. The separated khapada tiles, after drying, are piled up and fired by using straw as fuel. Using a Wooden Mould: When a wooden mould is used, it is in a semi-cylindrical shape. The mould is placed on the ground. The potter covers the mould with a layer of clay and beats the layer till it becomes uniformly thick all over. It is then detached from the mould and dried. The tiles produced by pressing the clay over the moulds are considered more durable and strong than the tiles made on the potter's wheel, which are light, thin, and brittle. Such tiles are liable to be blown away during strong winds; however, as they are cheaper they are still in use.

Craft in Architecture, Metal

The gilded roofs and finials of the temples and palaces in the Kathmandu Valley were created by the metal processing method of repoussé - that is, the beating out of forms and images from the reverse side of sheet metal. This method was also employed to make gilt copper overlays for carved wood in shrines such as Kwa Baha in Lalitpur, and at Changu Narayan. By the 7th century, at the latest, the artists of the Kathmandu Valley had mastered the arts of repoussé and also of inlay with semi-precious stones: this is proved by the inscriptions of the extensive use of metal for the beautification of temples and palaces. None of this remains, but it seems certain that many motifs and techniques date back at least this far - Chinese accounts mention water pouring from the mouth of a golden makara, a sight that may still be seen today. The influence of Newar metalwork has been formative in Tibet and China.

The gilded roofs and finials of the temples and palaces in the Kathmandu Valley were created by the metal processing method of repoussé - that is, the beating out of forms and images from the reverse side of sheet metal. This method was also employed to make gilt copper overlays for carved wood in shrines such as Kwa Baha in Lalitpur, and at Changu Narayan. By the 7th century, at the latest, the artists of the Kathmandu Valley had mastered the arts of repoussé and also of inlay with semi-precious stones: this is proved by the inscriptions of the extensive use of metal for the beautification of temples and palaces. None of this remains, but it seems certain that many motifs and techniques date back at least this far - Chinese accounts mention water pouring from the mouth of a golden makara, a sight that may still be seen today. The influence of Newar metalwork has been formative in Tibet and China.

THE ORIGIN OF CASTED METALWARE

The first recorded evidence of copper and bronze objects being produced in Nepal can be traced back to the early Lichhavi period and is found at the Chandeswari temple in Banepa and at Sankhu. These objects appear to date back to the 6 A.D.. Likewise, records from the Chinese traveller, Yuan Chuang, who passed through Nepal during the seventh century, describe his appreciation and admiration of Nepalese metal craftsmanship. So impressed were the Chinese by the artistry of Nepal's metal industry that the Chinese Emperor Kublai Khan invited one of Nepal's famous artists, Arniko, to help renovate Chinese metal structures in 1274. Evidence of Arniko's work can still be seen in the form of Boddhisattva, Lokeswara, Tara and the renowned white Nepalese pagoda that still remains standing in China.

By the early seventeenth century, Nepal became an important trading point between India and China. As this trade increased, the export of metal products to other countries in the region began to flourish. Even today, examples of early Nepali products can be found in Tibet, China, India, Pakistan, Burma and Bangladesh.

There is abundant evidence that under the Newars the art of building reached a high stage of perfection, while the profusion of ornamentation in wood-and metal-work attests the liberal encouragement that those arts received.

Patan, a city located adjacent to Kathmandu, has been considered by most experts to be the origin of the metal cottage industry in Nepal. The excellence in metal craftsmanship in Patan can be traced back to the fourteenth century with the creation of the 'Kwa Bahal' or Golden Temple. Likewise, records dating back to the mid-1500s, during the period when the Mahabauddha temple was being constructed, describe the flourishing metal industry in a section of Patan that surrounded this important shrine. Since copper deposits were readily available in the area, metal workshops were able to flourish. Even today, Patan remains a major focal point for the production of cast statues that are sold for export throughout the world.

During the mid-1700s, an important migration of metal craftsmen took place from Patan to three sites within Nepal - Tansen Chainpur, and Bhojpur. According to historical anecdotes, there were two explanations that account for this outward migration. The first related to the availability of raw materials. Chainpur and Bhojpur both had a good supply of copper. As the price of raw materials began to steadily increase in the Kathmandu Valley, it became more cost effective to move to a location where these materials were less expensive.

A second important consideration had to do with a custom known as a 'guthi', which still exists in Nepal today. A guthi represents a social organisation consisting of married brothers of a number of families who gather regularly for large, lavish feasts. These celebrations were organised by a different brother on a rotational basis. As the cost of the food and drink for these elaborate events began to exceed what the average family could afford, rather than just stopping the practice, entire guthis left Patan for other areas of the country, thus leaving the tradition behind.

Within the metal casting industry, most of the craftsmen who ply this trade come from the Newar community. For centuries, the Newars have been renowned throughout the world for their expertise in producing exquisite sculptures from a variety of materials including stone, wood and metal. They are also responsible for creating many of the impressive temples and palaces scattered throughout Nepal's major durbars and public squares. The Newars till today continue to attain the highest level of excellence in metal casting, which is unsurpassed. Newari brass and bronze metalware, including both religious and secular vessels and bowls, are admired for their functional use as well as for their high aesthetic value.

Craft in Architecture, Terracotta Bricks

The making of brick and tiles is among one of the oldest crafts of Nepal. According to the Buddhist manuscript Swayambhoo Puran - which deals with the origin of the Swayambhoo Chaitya in the Kathmandu Valley and the founding of the city of Kathmandu itself by Lord Manjusri - mention is made of brick and tile-making. Archaeology and a study of ancient buildings provide evidence to the excellence achieved during the Kirant, Lichhchhavi, and Malla periods in the history of Nepal. Temples and stupas made of terracotta bricks and belonging to the Malla periods still exist in Nepal, as evidence of the excellent workmanship practised there. Brick-making from the local clay of the fields is still an important indigenous craft technique and business in Nepal. Since stones are not readily found in the alluvial soil, most buildings here are of brick - the same material that has been used since the earliest times. With great foresight, the Kathmandu city fathers recently passed an ordinance allowing only buildings with brick faces to be built within the city limits.

The making of brick and tiles is among one of the oldest crafts of Nepal. According to the Buddhist manuscript Swayambhoo Puran - which deals with the origin of the Swayambhoo Chaitya in the Kathmandu Valley and the founding of the city of Kathmandu itself by Lord Manjusri - mention is made of brick and tile-making. Archaeology and a study of ancient buildings provide evidence to the excellence achieved during the Kirant, Lichhchhavi, and Malla periods in the history of Nepal. Temples and stupas made of terracotta bricks and belonging to the Malla periods still exist in Nepal, as evidence of the excellent workmanship practised there. Brick-making from the local clay of the fields is still an important indigenous craft technique and business in Nepal. Since stones are not readily found in the alluvial soil, most buildings here are of brick - the same material that has been used since the earliest times. With great foresight, the Kathmandu city fathers recently passed an ordinance allowing only buildings with brick faces to be built within the city limits.

TRADITIONS

Local brick-making is done in winter. It involves scooping the soil from a field and pressing it into a mould that releases a rectangular-shaped chunk when turned upside down. These blocks are fired in large, squarish kilns.

The shape and size of bricks vary. Ancient Nepalese bricks of the Lichhchhavi period were much larger in size than those being used today (8.75" X 4" X 1.75"). The brick-making specialist craftsmen in Nepal belong to a special class of farmers known as awa or awale. An expert awa, working for about 4-5 hours, can make a thousand bricks in a single day.

RAW MATERIALS, PROCESS, & TOOLS

The traditional method of brick-making by hand moulding, and baking in a kiln, is still practised. The chief tool, is the wooden mould of the required size and good-quality clay that is soft, plastic, and free from impurities - this is normally obtained from the fields where, often, makeshift brick kilns are erected on the spot. Sand that is fine, white in colour, and free from stone grits and other impurities, is another component, as is pancha clay, a well known variety of clay that is widely used as a water-proofing layer on open terraces and roof-tops before they are paved with tiles.

The clay that is collected is watered and allowed to remain wet for a day or two after which it is kneaded by trampling. This process is repeated once again after the clay has been scooped up and re-mixed with a spade. The clay is then ready for moulding.

The wooden mould is made slightly wet and some pancha clay or fine sand is sprinkled inside the mould. The awa then takes a roll of clay that is covered with sand on its outside and throws it with force into the mould. He then removes the excess clay with a metal wire. The mould is inverted and the brick comes out off the mould. The clay bricks are arranged in long rows on the ground for drying. They are dried for, at least, 15-20 days - if the bricks are not thoroughly dried, they tend to crack during the firing.

When enough bricks are ready the brick-makers start constructing the kilns. Traditionally, the up-draft and rectangular open-top kilns are used; a small-sized one can contain up to 25,000-30,000 bricks. These kilns are built up of the raw bricks, usually in the very area where the bricks are made. The kilns are about 15-20 feet long, 8-10 feet broad (at the base), and 15-20 feet in height. After the bricks are piled up, the firing is started at the base. The fire spreads till it reaches the opposite end of the kiln. At this stage, the fireplace is closed and the fire spreads to the upper part. This process of firing takes about 4-5 days. When the baking is complete the whole kiln is allowed to cool; thereafter one side of the wall is opened and the bricks are taken out. They are ready for use.

Craft in Architecture, Terracotta Dhuris / Roof Top Covers and Kuna-pakhas / Roof Corners

In traditional Nepalese homes and temples, which are roofed with Nepalese tiles, the roof-tops are further topped with a special kind of covering called dhuris. The corners of such roofs are also fitted with specially designed roof-corners known as kuna-pakhas.

In traditional Nepalese homes and temples, which are roofed with Nepalese tiles, the roof-tops are further topped with a special kind of covering called dhuris. The corners of such roofs are also fitted with specially designed roof-corners known as kuna-pakhas.

DHURIS (ROOF TOP COVERS): PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

Long elevated slopes of clay that serve as moulds for the dhuris are first shaped on the ground. The potter places a lump of clay a little bigger than the actual measure, over which is placed the iron frame. The clay is spread over this - excess clay is removed by cutting it with a knife. The surface of the dhuri is smoothened with wet fingers and a wooden plank. Next, one edge of the dhuri is shaped so that it is elevated, and two wooden rods are placed on the two sloping sides so as to create a depression. After the elevated edges are cleaned - by rubbing them with wet fingers - the wooden rods are removed. The dhuri is left on the raised mould to dry. This process is then repeated. On an average, 50 dhuris can be made in one day.

KUNA-PAKHAS (ROOF CORNERS): PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

To make the kuha-pakha, a squarish, pyramid-shaped mound of clay is first raised on the ground. (This mound works as the mould). The four-sided mould is covered with a uniform layer of clay of the required thickness. The potter then places an iron measure on one side of the square mound, and cuts off the clay according to the measure. The part is then smoothened with wet fingers. The next step is the shaping of the corner into a raised cock's head. This process is repeated in the remaining three corners. The kuna pakhas are then dried. On an average, 20 kuna-pakhas can be made in one day.

Craft in Architecture, Terracotta Teliya Bricks and Paving Tiles

These special kind of bricks and paving tiles are called chikan appa, implying that they are made of oil. Although no oil is actually used in their making, their smooth and glossy surface appears to have a coat of oil. Specimens of these teliya (tel = oil) bricks and paving tiles - with their characteristic red, smooth, and shiny surfaces still intact - can still be seen in old temples, houses, and courtyards.

These special kind of bricks and paving tiles are called chikan appa, implying that they are made of oil. Although no oil is actually used in their making, their smooth and glossy surface appears to have a coat of oil. Specimens of these teliya (tel = oil) bricks and paving tiles - with their characteristic red, smooth, and shiny surfaces still intact - can still be seen in old temples, houses, and courtyards.

PROCESS & TECHNIQUE

The potter wets the wooden mould by dipping it in water, sprinkles some dry pancha clay into the interior of the wet mould, and throws a lump of clay into it. Excess clay is cut off by means of iron knife or a wire. The potter lifts the mould and the tile drops on to the ground automatically. When the tile is sufficiently dry, it is smoothened by rubbing and beating with a small wooden hammer.

When the tiles are hard enough, they are piled up for firing. Before they are fired, they are given a wash of lancha clay (a ferrogenous clay with a high percentage of iron oxide) on the upper side. This wash makes the bricks red.

Craft in Architecture, Woodcarving

The profusion of carved wood in the old Newar towns in the Kathmandu Valley is so great that it almost defies description. Every traditional townhouse, every temple and monastery, and every palace, offers examples of an enormous variety of carved doors, windows, struts, pillars, toranas, and so on - many of these are unique in themselves. Wood was the medium through which the artistic exuberance of the Newar craftsperson was expressed to the fullest. According to tradition the valley of Kathmandu derives it name from kastamandapa meaning a temple built from wood of a single tree which it is believed was constructed some 800 years ago. Until the comparatively recent past, much of Nepal remained richly forested and timber was readily available. It was therefore used extensively in local architecture, much like it was in the architecture of Kashmir, of the Himalayan districts of India and, further east, of Bhutan. Wood was used both structurally and for the decoration of buildings in the Kathmandu Valley; as time went on, its decorative function seems to have outstripped its structural role. Thus, although doors and windows are obviously necessary for access to a building and to provide both light and air, they increasingly became more like vehicle for the artistic endeavours of the woodcarver, to the extent that many of Nepal's richly carved temple doors were never meant to be opened, and that there are windows that serve to illuminate upper storeys where no human being has ever ventured, or ever will. The Newars have a rich vocabulary, particular to them, to describe the tools, components, decorative motifs, and patterns used in woodcarving - many of the Newars' techniques and compositions follow the stipulations of medieval Vastuhastra texts such as the Manisara. Typically, the components of a wooden artefact such as a window frame or a door are assembled without the use of metal nails or glue, although wooden pins are used on occasion. For the exterior of the buildings the craftsmen use a hard wood which is not easily destroyed by sun, wind or rain. Their first choice is therefore the hard sal wood that is seasoned for several years before it can be used. Chanp, pine, cedar, sissoo varieties of wood are used for carving objects that are not exposed to the elements. The sal wood that is used for exterior decoration requires the carvers to put in extra hours of work and exercise great care while working - the carvings on such wood is a far more painstaking job. However if there is proper upkeep and care the wooden doors and windows can last for many decades.

The profusion of carved wood in the old Newar towns in the Kathmandu Valley is so great that it almost defies description. Every traditional townhouse, every temple and monastery, and every palace, offers examples of an enormous variety of carved doors, windows, struts, pillars, toranas, and so on - many of these are unique in themselves. Wood was the medium through which the artistic exuberance of the Newar craftsperson was expressed to the fullest. According to tradition the valley of Kathmandu derives it name from kastamandapa meaning a temple built from wood of a single tree which it is believed was constructed some 800 years ago. Until the comparatively recent past, much of Nepal remained richly forested and timber was readily available. It was therefore used extensively in local architecture, much like it was in the architecture of Kashmir, of the Himalayan districts of India and, further east, of Bhutan. Wood was used both structurally and for the decoration of buildings in the Kathmandu Valley; as time went on, its decorative function seems to have outstripped its structural role. Thus, although doors and windows are obviously necessary for access to a building and to provide both light and air, they increasingly became more like vehicle for the artistic endeavours of the woodcarver, to the extent that many of Nepal's richly carved temple doors were never meant to be opened, and that there are windows that serve to illuminate upper storeys where no human being has ever ventured, or ever will. The Newars have a rich vocabulary, particular to them, to describe the tools, components, decorative motifs, and patterns used in woodcarving - many of the Newars' techniques and compositions follow the stipulations of medieval Vastuhastra texts such as the Manisara. Typically, the components of a wooden artefact such as a window frame or a door are assembled without the use of metal nails or glue, although wooden pins are used on occasion. For the exterior of the buildings the craftsmen use a hard wood which is not easily destroyed by sun, wind or rain. Their first choice is therefore the hard sal wood that is seasoned for several years before it can be used. Chanp, pine, cedar, sissoo varieties of wood are used for carving objects that are not exposed to the elements. The sal wood that is used for exterior decoration requires the carvers to put in extra hours of work and exercise great care while working - the carvings on such wood is a far more painstaking job. However if there is proper upkeep and care the wooden doors and windows can last for many decades.

DETAILS OF DOORS & WINDOWS

Doors and windows, both functional and purely decorative, are often the most lavishly decorated elements of a traditional Newar building. It is not only the frames that were decorated - because glass was not used in Nepal until quite recently, it was necessary to find a way to block out the elements and the prying eyes of passers-by while admitting light, and the solution was a wooden latticed screen. This form probably developed from essentially utilitarian considerations sometime before the 12th century, but by the middle of the Malla period it had become immensely diverse.

The general term for a latticed Newar window is tiki-jhya or tika-jhya, 'jhya' being the Newari word for 'window', which has entered Nepali as 'jhyal'. Within this general category there are specific terms for particular varieties of tikijhya. For instance:

- gah-jhyas, yaku-jhyas, baku-jhyas, and chaku-jyas are all different kinds of blind windows

- gua-jhya is a round window

- chapa-jhya is a heavy-framed multiple window

- lun-jhya is a gilded window

- gumbaj-jhya is an arched window that may be flush with the wall or projecting and have single or several openings.

The window-screen of a tiki-jhya is not carved from a single piece of wood. Instead, three different kinds of slender batten are sawn from a plank, carved into decorative designs, and then fitted into one another, either at right angles or at 450. The design carved on to the battens may be, among others, a line of circles, squares, diamonds, vajras, flowers, chains, or stars. The assembled lattice is then dovetailed tightly into a window frame, and there it remains, often for centuries, since it is almost impossible to remove it without dismantling the frame. Sometimes, another carved wooden figure or design is imposed on the screen there: this is more common in the windows of palaces and temples than those of residential dwellings, but is by no means exclusive to the homes of gods or kings. Some of the best-known examples of this are the 'Peacock Windows' at Pujari Math in Bhaktapur and Kumari Baha in Kathmandu, and elsewhere besides. However, many other figures may also appear at the centre of the lattice: a sun emblem (with five or nine horses drawing the sun's chariot, represented beneath the screen), deities such as Durga, Bhairav, or Ganesh, and floral designs or auspicious symbols.

- There exists a rich heritage of design in the carving of the windows. The most popular motifs and designs include the lotus, chariot, peacock and sun window motifs, the corner and balcony window, circular window, the mesh window, the window with a bow frame, an assembly of three to five windows, the halved window and others. There are also many variations in the placement of the windows, for instance a single inset window can be sandwiched in between multiple windows; windows can also be artistically placed under the roof of the temple. The arched panel of the window and the toran or decorated panel fixed at the top, also have marvellous wood carvings.

- The door frames are carved with images that symbolise good fortune, peace and happiness. They include floral designs, images of gods and goddesses, carvings of the eyes of the Buddha, designs of the traditional religious water pot (kalash), fish etc. The doors consist of either a single or double shutter and are made of soft wood when they are not exposed to the sun or rain and of hard wood if there is exposure.

Crafts in Architecture,

NAQQASHI/ KAMANGARI/ RELIEF FRESCOS A number of historical buildings in Pakistan display fine work in fresco done by artists several centuries ago. The ceiling and upper portions of the walls of the ante-chambers at Emperor Jehangir's Tomb in Lahore are wholly covered with decorative paintings and no visitor to the Wazir Khan Mosque can fail to appreciate the exquisite carpet-like patterns painted on the interior of its domes. This craft, called naqqashi and kamangari, also flourished between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries and was perfected by artists working in Thatta, Lahore, Chiniot and Hyderabad. During the British period most of the artisans were forced to look for alternative means of livelihood. However, those who persevered in the family tradition found an opportunity to utilise their skills when restoration of old monuments was taken up some years ago. While genuine naqqashi is done with watercolours on freshly laid lime plaster, quite often the artisans are required to work on old surfaces and then they use oil paints. In the past they made their own brushes (qalams) of goat's hair for broad strokes and squirrel's hair for fine work, and used vegetable colours. Now some of them have begun to depart from the tradition by using imported brushes and synthetic dyes. Another indigenous tradition is the use of milk and curd, in addition to water, in the preparation of lime paste. One a small-scale naqqashi is also done on wooden panels.

NAQQASHI/ KAMANGARI/ RELIEF FRESCOS A number of historical buildings in Pakistan display fine work in fresco done by artists several centuries ago. The ceiling and upper portions of the walls of the ante-chambers at Emperor Jehangir's Tomb in Lahore are wholly covered with decorative paintings and no visitor to the Wazir Khan Mosque can fail to appreciate the exquisite carpet-like patterns painted on the interior of its domes. This craft, called naqqashi and kamangari, also flourished between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries and was perfected by artists working in Thatta, Lahore, Chiniot and Hyderabad. During the British period most of the artisans were forced to look for alternative means of livelihood. However, those who persevered in the family tradition found an opportunity to utilise their skills when restoration of old monuments was taken up some years ago. While genuine naqqashi is done with watercolours on freshly laid lime plaster, quite often the artisans are required to work on old surfaces and then they use oil paints. In the past they made their own brushes (qalams) of goat's hair for broad strokes and squirrel's hair for fine work, and used vegetable colours. Now some of them have begun to depart from the tradition by using imported brushes and synthetic dyes. Another indigenous tradition is the use of milk and curd, in addition to water, in the preparation of lime paste. One a small-scale naqqashi is also done on wooden panels.

The naqqash knows no limit to his choice of design or colour. Broadly the designs are divided into four categories: floral (gulkari), geometrical (chitsali), calligraphic (khattati), and painting from life or nature (musawwari). Quite often the design and the colour scheme is the combined work of the moulder and the painter: the former divides the surface into rectangular or polygonal frames and the latter fills these frames with the desired designs.

In recent years the crafts of moulded pottery and kamangari have been fused together to produce painted vases, flowerpots and wall-plates. They are made of plaster of paris in a large variety of shapes and display a wide range of motifs, from the traditional floral patterns to European designs and legends, painted in different colours. In simpler models the painting is done on plain surface but many artisans apply the colours on patterns in relief.

STUCCO TRACERY/MANBAT KARI

Manbat is an Arabic word. It has two meanings: A place where plants grow; and also a place for ornamental work done in relief, i.e. embossed. Stucco is a term used for a fine plaster. This plaster is composed either of (1) fine sand, powdered marble, and gypsum mixed with water or, as in South Asia, white lime cream, surkhi (powdered brick) and fine grimixed with water. The first formula is more effective and affords quick working and results in a better uniform and glossy surface.

In the world famous and noblest work of the fine minute stucco tracery at the Alhamra (1334-91 AD) in Spain the gypsum formula was used which in the course of time takes an Ivory colour. In South Asia, Stucco was known as early as the first century A.D. As is evident from the Stucco Tracery discovered from the Apcidal Temple (1st Century AD) at Sirkap at Taxila, but the work of stucco tracery in the sense we use now was not practiced here before the Muslim rule in India.

THE MOSAIC WORK

This very impressive, charming and durable decorative work took its origin in its broader form during the Achae BC. However in its minute form it became the chief decorative feature in the monuments of the safavid period 1602-1722 AD in Iran from where it was projected to Lahore in the early 17th century AD. It is worked with small pieces cut to the desired shape from enamelled tiles of various vivid colours and then joined to form different floral, geometrical, calligraphic and figural forms in one plane. However, at Lahore it surpassed even the scope of Iranian work. The most graphic and realistic representations showing flora, fauna, animal, portraiture are to be seen at the North and West wall 1st half of 17th century AD of the Lahore Fort. Floral motifs, plant life and calligraphic decoration in the mosque of Wazir Khan in Lahore 1634-35 AD are specimens of unsurpassed beauty, skill and workmanship of this craft in Pakistan.

Craved and Turned Wood Work of Hosahiarpur, Punjab,

Deodar and sheesham sourced from the local market are used as raw materials for producing a wide array of utilitarian objects. The production clusters center around Hoshiarpur, Amritsar, Jalandhar and Batala Quadian. Objects such as chairs, peg tables, singhardaani containers, peedi, wooden slippers called khadavan, butter churners, rolling pins, gridles, beds and screens etc. are meticulously crafted. Tolls such as chisel called chorsi locally, fine- sutna, tool sharpner-pathri, saws, clippers, planers and drills are used in the process of crafting the wood.

Deodar and sheesham sourced from the local market are used as raw materials for producing a wide array of utilitarian objects. The production clusters center around Hoshiarpur, Amritsar, Jalandhar and Batala Quadian. Objects such as chairs, peg tables, singhardaani containers, peedi, wooden slippers called khadavan, butter churners, rolling pins, gridles, beds and screens etc. are meticulously crafted. Tolls such as chisel called chorsi locally, fine- sutna, tool sharpner-pathri, saws, clippers, planers and drills are used in the process of crafting the wood.

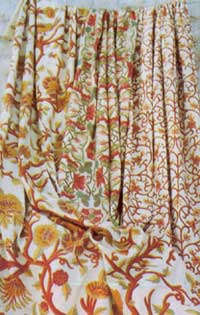

Crewel Embroidery of Kashmir,

Kashmiri embroidery, popularly known as Kashida, along with the Kashmiri carpet industry, is one of the biggest commercial crafts of India. Though the embroidery originated in the form of shawl ornamentation, it is now used to decorate a range of articles including yardage, home furnishings, jackets, coats, mufflers, jutis (leather footwear) etc. Kashida has several forms

Kashmiri embroidery, popularly known as Kashida, along with the Kashmiri carpet industry, is one of the biggest commercial crafts of India. Though the embroidery originated in the form of shawl ornamentation, it is now used to decorate a range of articles including yardage, home furnishings, jackets, coats, mufflers, jutis (leather footwear) etc. Kashida has several forms

- Zalakdozo (a chain stitch done with hook on almost every fabric from shawl to floor covering)

- Suzni (only done on fine fabrics using three types of stitches. The embroidery is completely symmetrical on either ends of the fabric)

- Vata chikan (buttonhole stitch used to cover large sections of the fabric. Landscapes and crowded scenes are commonly depicted)

- Do-rookha (double sided work where both sides of the fabric are mirror images)

- Amli (a new innovation in kani or jamevar shawl, delicate filling with stitches using multicoloured threads in elaborate all over patterns to enhance the fine layout of the kani).

ABOUT Crewel Embroidery

Crewel or Hook embroidery, locally known as Zalakdozi, is one of the specialized styles of embroidery practiced in Kashmir. Several articles are made using this embroidery - Namda (felt carpet), dress material and curtain cloth. The base cloth is the same for these items and that determines what the product will be used for and what manner of decoration will be done on it.

|

DESIGNS AND COLOURS

The designs range from Persian to French, from Chinar leaf (Chinar is an important tree in the Valley and its leaf has been amply used in embroidery), Shikargarh (hunting scenes), Theridar, Bulbuldar, Guldar, Badamadar (buta resembling an almond which is believed to be in use from the first quarter of the 18th century), Kalka (most popular flame shaped motif) etc.

|

The base colour of the fabric is generally cream or white or similar pastel shades. A wide range of colours are used by the Kashmiri embroiders for the embroidery yarns including crimson (gulnar), scarlet (kirmizi), white (sufed), green (zingari), dark green (siah sabaz), light blue (asmani), blue (firozi), yellow (zard and sharbati), purple (uda) and black (mushki). Earlier the yarns were dyed exclusively in vegetable dyestuff but today synthetic dyes are increasingly used. Though wool and cotton are still popularly used for embroidery, rayon and artificial silk have replaced the natural silk threads and they are all mill-made.

PROCESS

The design is traced onto the fabric by professional tracers called Naquashband. They have perforated sheets with innumerable designs and they lay these sheets on the fabric and chalk or charcoal powder is rubbed over it, which leaves the impression of the design on the fabrics surface. Gum Arabic or oil is added to the powder to make the tracing durable. The outlines are highlighted using a wooden pen (kalam).

|

After tracing the design, the embroider (zalakdoz) works with a hook needle (Ara Kunj) inserting the hook from the right while the thread is held on the underside. The design shows itself in the form of small loops. The work appears as a chain stitch on the surface. While maintaining the same quality, hook work covers a much larger area than needle work in the same amount of time.

The intrinsic worth of each piece lies in the sizes of the stitches and the yarn used. Tiny stitches are used to cover the entire area - the figures or motifs are worked in striking colours; the background in a single colour, made up of a series of coin sized concentric circles which impart dynamism and a sense of movement to the design. Stitches ought to be small, even sized and neat. The background fabric should not be visible through the stitches.

|

All the embroidery in Kashmir is done by men. Being a hereditary craft, the son is apprenticed in his father's workshop from the age of 8-10 years. It is believed within the community that it takes 16 years to master the craft.

Cut Glass Mirror Work of Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu,

This is mainly practised in Thanjavur where painted wooden figures are decorated with broken or cut glass and further embellished with gold and silver paper or foil.

This is mainly practised in Thanjavur where painted wooden figures are decorated with broken or cut glass and further embellished with gold and silver paper or foil.

Cut Glass of Punjab,

Amritsar, in Punjab has a fine tradition in glass ware and the products made here are exported in large quantities. These products are mostly elegant utility items. The raw materials used vary from region to region, the two main raw materials being old broken pieces of melted glass or a mixture of sand stone powder and carbonate of soda. In some places, carbonate of soda is mixed with saltpetre and then alkaline earth and water are heated to serve as raw materials. The glass items are adorned with floral designs. A finer variety of glass --- using old glass with red sand stone, carbonate, and saltpetre --- is made in Panipat.

Amritsar, in Punjab has a fine tradition in glass ware and the products made here are exported in large quantities. These products are mostly elegant utility items. The raw materials used vary from region to region, the two main raw materials being old broken pieces of melted glass or a mixture of sand stone powder and carbonate of soda. In some places, carbonate of soda is mixed with saltpetre and then alkaline earth and water are heated to serve as raw materials. The glass items are adorned with floral designs. A finer variety of glass --- using old glass with red sand stone, carbonate, and saltpetre --- is made in Panipat.

Cut Work Weaving of Uttar Pradesh,

The cut work of Banaras is a cotton inlay in cotton developed for furnishings, especially drapes, where it helps cut down the glare of the mid-day sun. Extremely popular with the urban consumer, the design repertoire covers geometric, floral, and paisley patterns. The technique is suitable to light and transparent fabrics and the motifs are formed with extra weft threads which hang loosely at the back. After weaving these threads are cut away.

The cut work of Banaras is a cotton inlay in cotton developed for furnishings, especially drapes, where it helps cut down the glare of the mid-day sun. Extremely popular with the urban consumer, the design repertoire covers geometric, floral, and paisley patterns. The technique is suitable to light and transparent fabrics and the motifs are formed with extra weft threads which hang loosely at the back. After weaving these threads are cut away.