The craft of weaving wool is a characteristic of the hills of Uttarakhand, initiated by the women of the villages. This craft has become indivisible from the lives of the natives, the Bhotias and the Gadvalis, even though the craft only took roots in the region just 3-4 generations back. Earlier a few nomadic tribes undertook the task of weaving woolen carpets, however now many more people have taken to the craft, and are weaving a variety of products. Many organizations have set about the task of teaching weaving and setting up looms to help the craft prosper. When talking about the craft, woolen carpets of the Bhotia are the most famous and the oldest form of the craft. Bhotias are a Tibetan nomadic tribe in Uttarakhand. Their winter months are spent in Dhunda, in an effort to obtain wool and weave fabrics while the summer months are spent in Harsil, growing beans, potatoes, apples and almonds. The charge of rearing sheep and procuring and preparing the wool is taken up by the tribe itself. September to October is considered to be the business time. Traditionally yarn is spun on the spinning wheel or the Charkha, after which it is ready to be knitted or woven. Two types of looms are taken in to use while weaving. For the coarser wool an upright loom is used while for finer wool the pit loom is used. Knitting, done with a pair of needles has attained a different level of fabric construction altogether with the motifs transforming into three dimensional textures. Sheep wool is often mixed with rabbit hair to attain extra softness, shimmer and whiteness to the weave. Once the fabric is made, it is washed and brushed to give a felt like effect. As a result of the blending of white and black wool in definite ratios, before spinning of the yarn, different shades of grey in the woolen fabrics area naturally obtained. Tibetan motifs which have a higher demand, has replaced the traditional Bhotia designs. The designs can be characterized by two broad categories, stylized geometric motifs and the floral and dragon designs exhibiting a Chinese influence. While many carpets are woven from memory, typically the design is followed by looking at the reverse of a finished carpet or from a colour graph. Bhotias sell their woolen products at annual fairs at Bageshwar, Jaulgibi and Thal. The Tibetan carpets have a popular international market too. Popular products made the Bhotias are knitted Kangsuk (socks), Saai (cap), Laakshu (glove), mufflers and woven suit lengths, shawls, dan (carpet), stoles, dumkar (banket) and paagad (belts).

In the high altitudes of Himachal Pradesh, sheep and goat rearing is a very common occupation for many villagers who are involved in blanket-weaving and felting. The Giabong and Kulu valleys are the main areas for gudma, the local name for a fleecy, soft, and heavy blanket which is woven by the local villagers in natural colours and finished with a warm red or black trimming. Mattresses locally called kharchas are made of woollen yarn derived from goat's hair. Numdha, a craft fairly new to Himachal Pradesh involves felting the wool and ornamenting it with colourful embroidery threads. The carpets of Himachal are rich and captivating in design and durable in texture. Dragons borrowed from the neighbouring country of China and the Hindu swastikas are popular motifs which get incorporated in these carpets. Many Tibetan craftspersons are engaged in weaving woollen carpets in the villages of Bhuppur, Puruwala, Sataun, and Kamsan in the Paonta block of Sirmur district. The cold climate in the hills in this region makes the carpet an item of daily use. The patterns woven are mainly geometric and blocks of colour are used in the patterns. Threads of ground colours are used; they are cut off when a new motif or design has to be introduced. The weaving is a combination of cotton and wool and it is done by women. Bhutias are traditional weavers who make common bedside carpets called duns with 60 knots to a square inch. Asans, with squares to sit on, are also made. The motifs are inspired from alpana or rangoli designs drawn on the floor during festive occasions and they are geometric or floral. Mythical Tibetan birds called dak, jira, dragons, lions, and the god of lightning are common motifs. The Central Asian influence can be seen in the presence of the famous key and swastika designs. Chali is a coarse carpet found in Lahaul which is a remote mountainous area in the far north. Kinnaur in Himachal pradesh is noted for its fine weave. The residue wool left after the material for pashmina shawls has been taken is used to weave a rough yarn called sheli from which carpets --- called karcha, chuktu, and chugdan --- are made. Black and white carpets are woven from a mixture of sheli and bakratha, another kind of goat's wool Thobis are black and grey carpets made from goat's hair at Pangi in the Chamba district of Himachal Pradesh. The motifs found on these carpets are the trishul (trident), the swastika, and an eight-pointed design made of a combination of a diamond and a concentric circle. Although wool carpets are predominant in the region, a wide range of cotton dhurries are also made. The main colours used are red or blue, and the design comprises usually of stripes. Weavers of Sirmur use pit-looms. Varying effects are produced by using yarn of differing thicknesses, thin for the warp and thick for the weft.

Carved and turned wood work is widely practiced across several regions in Punjab.Products like chairs, peg tables in Hoshiarpur, containers called singhardaani in Jalandhar, low stools called peedi, wooden slippers called khadavan, butter churners, rolling pinks, wooden handles for tava, chairs, tables, beds and screens in Batala. Tools such as chisel, file, tool sharpener, saws, clippers, planers and drills are required for the crafting process.

The Bhutanese do carving extensively in wood, slate or stone, for making items such as printing blocks for religious texts, masks, furniture, altars, and the slate images adorning many shrines and altars. Carving, however, is not confined to wood stone and slate only - some of the most exquisite and rare carving of images of deities has been done on rhino horns and ivory and adorns various temples.

In Nepal, though the terracotta tradition goes back more than three millennium, the introduction of glazes and the porcelain craft is relatively new. Unlike other countries in South Asia, earthenware products were rarely used for cooking or for eating; metal was always the material of choice in Nepal.

Products ranging from blankets, rugs, storage bags and saddle bags are produced under the challi craft. The required tools are ground loom, shuttle, spindle, needle and scissors.

Althought embroidered through Himachal the embroidery is associated specifically with Chamba owing to the patronage by rulers of the area. Traditionally, the Chamba rumals were embroidered on square pieces of fabric that were used to cover offerings of food, gifts, offerings to a deity, gifts exchanged between the families of the bride and the groom and other purposes. Chamba rumals have been called 'paintings in embroidery' due to the theme being similar to those painted on miniatures. Practiced by women from all strata of Pahari society, the embroidery style differed between the folk and the court styles. The style developed by the court, embroidered by the women of the upper classes and the royalty has now come to be exclusively related to the craft. Though some themes were similar all else differed as artists trained in the Pahari miniature tradition often rendered the base drawing on which the embroidery was done, often providing the color palette too, for upper class women to follow. Themes centered on the depiction of the God Krishna and his devotees. They included scenes from the Raaslila, Raasmandal , the Ashtanayika, Godhuli - literally the'hour of cowdust' when Krishna and his cowherd friends bringing the cows back at dusk and other themes, While the folk tradition used vibrant colours the court tradition used subdued, coordinated shades. Traditionally, the Chamba rumals were embroidered on square pieces of handspun and handwoven unbleached fine mulmul cloth The embroidery was done using untwisted silk yarn in a double satin stitch technique known as dorukha, where both sides of the embroidered cloth were identical. The embroidery yarn and stitch is similar to the Phulkari embroideries of Punjab. Court themes included other subjects relating to the lives of the embroiders and often derived from the wall paintings of the Rang Mahal of Chamba and the Pahari miniature tradition including the royal hunts, the game of dice - chaupad. Products embroidered now include caps, hand held fans, blouses, dress material, table and household linen etc. There has been a revival of this tradition with the Delhi Crafts Council working to create pieces based on the court tradition.

-

The visualisation of the theme to be embroidered.

-

The outlining of the initial drawing in charcoal by a trained miniature artist.

-

The predetermination of a colour palette to be used while embroidering the rumal.

-

The actual embroidering of the rumal by the elite women along the designs sketched in charcoal by miniature artists.

2. CLOTH, THREADS & STITCHES The fabric used to make the Chamba rumal was hand-spun or hand-woven unbleached thin muslin or malmal. The thread used for the embroidery was untwisted silken yarn, which, in the do-rukha stitch used in Chamba embroidery, has a three-dimensional effect, creating tones of light and shade. This untwisted silk thread - usually made in Sialkot, Amritsar, and Ludhiana - was the same as that used in the Phulkari embroidery of the Punjab.

The stitch used in embroidering the Chamba rumal was the do-rukha, a double satin stitch, which, as its name implies, can be viewed from two (do) sides or aspects (rukh). The stitch is carried both backward and forward and covers both sides of the cloth, effecting a smooth finish that is flat and looks like colours filled into a miniature painting. No knots are visible, and the embroidered rumal can be viewed from both sides. It thus becomes reversible. A simple stem stitch using black silk thread is used to outline the figures. Other stitches like the cross stitch, the button-hole stitch, the long and short stitch, and the herring-bone stitch, as well as pattern darning, were also used occasionally.

-

Ganesha: The mythical Hindu god with the head of an elephant is represented with the main figure 'placed under a scalloped arch, with a green-leaved tree serving as an umbrella'. (Original rumal in the Indian Museum, Kolkata.)

-

Shikar: Representing a pastime common to royalty and feudal lords, shikar depictions represent ' a lively scene of movement', with details that include the 'variety of prey, the different weapons used, variegated colours for the animals [and the foliage] as well as the patterns of [the] dresses [worn by] the hunters'. (Original rumal in the Indian Museum, Kolkata.)

-

Godhuli: Literally, 'the hour of cow-dust', this refers to a rural scene: the cloud of dust that is raised when the cows return home at dusk. Often Krishna and his cow-herd friends are depicted bringing back the cows, a picturisation made more colourful by depictions of women watching, birds flying, nad fish swimming in the water. (Original rumal in the Calico Museum, Ahmedabad.)

-

Radha-Krishna: The depiction of Radha and Krishna on a pavilion is extremely colourful. The pavilion is two-tiered: Radha and Krishna, with attendants are on the first pavilion, while music and other activities are taking place on the ground floor. Depictions of trees, peacocks, and birds indicate that the pavilion is in the garden. (Original rumal in the National Museum, New Delhi.)

-

Raasmandala with Lakshmi-Narayana

- The raasmandala or the various raaslilas of Krishna are popular subjects, especially as they combine colour, activity, and movement. In the rumal that depicts the Raasmandala with Lakshmi-Narayana, a 'four armed Vishnu and Lakshmi are seated on a double-petalled lotus, flanked by adoring monkeys). Around them dance five blue-skinned Krishnas, interspersed with five gopis. There is a 'male drummer in the forefront', and 'women musicians in ecah corner'. 'The spaces are interspersed with beautiful flowering shrubs and peacocks' in vibrant colours. (Original rumal in the Indian Museum, Kolkata.)

-

Parijata Hara: Parijata or kalpa-vriksha, the boon-giving tree, was 'one of the treasures churned out of the ocean' in the great samudra-mathan (samudra = ocean; manthan = to churn). The tree was taken by the God of war (and rain), Indra, for his garden. The story depicted by the rumal is that of the theft (haran = abduction/theft) of the tree by Krishna, and the ensuing fight in the heavens between Indra ('seated on his white elephant') and Krishna ('seated on Garuda'). (Original rumal in the Crafts Museum, New Delhi.)

-

Jagannatha: This depicts the divine triad of the Jagannath temple at Puri (Odisha) - Jagannath, Subhadra, and Balaram - with bowls of offerings placed before them. 'The first floor enshrines the crowned figure of Krishna along with Radha. (Original rumal in the Bhuri Singh Museum, Chamba.)

-

Chaupad: This is a representation of the game of Chaupad or dice that was popular in the Chamba area The X-shaped base on which the game was played is depicted in detail; [f ]our couples, smoking hukkas (pipes) are shown playing the game.' (Original rumal in the Bhuri Singh Museum, Chamba.)

-

Ashtanayika: Representing the popular subject of 'nayika-bheda' (various moods of the nayika), this has 'eight drum-shaped panels in two rows'. Each cell depicts the nayika in a distinct mood and in varied surroundings. The moods are depicted through expressions, gestures, and through surrounding motifs, including the peacock and doves. (Original rumal in the Bhuri Singh Museum, Chamba.)

-

So far, the oldest dated rumal is a 16th century creation that is supposed to have been embroidered by Bebe Nanki, the sister of Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh faith in India. This is now preserved in the Sikh shrine in Gurdaspur in Punjab.

-

A rumal depicting the battle of Kurukshetra - from the Indian epic Mahabharata - is to be found at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. This oblong piece is supposed to have been presented by Raja Gopal Singh of Chamba to the British in 1833.

- Bhuri Singh Museum, Chamba (Himachal Pradesh, India)

- Crafts Museum, New Delhi (Delhi, India)

- Government Museum, Shimla (Himachal Pradesh, India)

- Indian Museum, Kolkata (West Bengal, India)

- National Museum, New Delhi (Delhi, India)

- Victoria & Albert Museum, London (United Kingdom)

- Textual & Photographic Material on the rumal is available with the Delhi Crafts Council.

Champa Silk Saree are peculiar to the state of Chattisgarh. The saree is developed from wild tussar silk (Antheraea mylitta). Since the texture of the yarn is rough, the saree too has a rough texture. The patterning is done with contrasting extra weft yarns on jacquard looms. The designs are inspired by tribal motifs. The product range developed out of tussar silk includes a wide range of sarees, dress materials, stoles, dupattas and home furnishings.

The gossamer-like chanderi derives its name from ancient town of Chanderi in Guna district of Madhya Pradesh. The fine chanderi has been compared with the fine Dhaka/Dacca muslin (which could pass through a ring).

| FIELD | BORDER | END-PIECE | |

| Lightest Muslin | Plain | Very narrow border of complementary-warp zari | Few narrow zari bands, or one single wider band. |

| Common Chanderi | Buttis appear in the field | Broader borders in supplementary-warp zari, with coloured supplementary-warp silk embellishments woven into small, repeat geometrical or floral designs | Border elements repeated twice, often with narrow woven lines and buttis. Minakari [inlay] effect most common in this. |

| Do Chashmee Two Streams (NO LONGER MADE) | Wide borders with brightly-coloured supplementary-warp silk in a satin weave upon which were supplementary bands of white geometric patterns. (In some saris the borders were reversible). | Relatively insignificant: with either two narrow or one wide band of zari or coloured silk woven in |

The main centres for this craft are Cuttack in Odisha and Karim Nagar in Andhra Pradesh. Traditionally the ingots were beaten on an anvil and elongated into long wire by passing them through a steel plate with apertures of different wire gauges. Each filigree jewellery piece actually combines several component parts.The space within the frame is filled with the main ribs of the pattern which is usually a creeper or flower, forming itself into small frames of circles, flower petals, and the like. Karim Nagar in Andhra Pradesh has long been noted for its silver filigree work. This traditional craft requires delicate workmanship. The products made include ashtrays, boxes, cigarette cases, trays, bowls, spoons, pill boxes, jewellery, buttons, paandans,, and perfume containers in the shape of peacocks, parrots, or fish. The jewellery made here has twisted silver wire as the base material; the articles have a lacy, trellis-like appearance which gives them a rare charm. Two or three wires are wound together after heating and then bent into various shapes to get patterns. The components are fixed together by a special method in which small square strips of an alloy of copper and silver known as tankam are spread to make the entire design, and then placed on the furnace. When well heated, dry paddy husk is sprinkled on it; this bursts into flames and melts the tankam pieces. The molten tankam penetrates into crevices and ensures the firm binding of the small pieces that comprise the whole. The block is then cooled in cold water. The smaller articles are directly moulded into various designs. For larger articles, smaller ones are made and pieced together. The main ribs are first fixed and the interstices are filled in with delicate tendrils or circular pieces which gives the article its special character. Karim Nagar has its own unique patterns and the elaboration in filigree is according to the pattern. A design with a high level of traceries is known as the Karim Nagar design. This is visible mainly in the perfume containers made in Karim Nagar, a product for which the place is famous.

Sarkanda plant grown abundantly in the green state of Haryana during the season of winter it gets dried up, is harvested and is then put to creative usage by the local folk. The dried main stalk is harvested and creatively used to produce collection of products. The thicker parts are used to make stools and furniture while the outer skin is used as thatch. The tuli, top half and the leafy covering, moonj is made into baskets Changeri is one of the many moonj grass products which are popularly made by local women folk. It is a traditional shallow basket made by coiling technique and often with a lid. Besides the Changeri they make the large boiya roti/bread basket, that may or may not have a lid but nonetheless keep hot rotis dry and fresh due to its moisture absorbing walls. A variation of the changeri is the Sindhora a pear shaped basket that is bound with naulai or wheat stalk. These baskets are decorated with gota/shiny ribbons, colored threads, date palm and patera leaves. The women also make hand fans to keep the heat away and the indhi, used as a support base for carrying water pots on the head are also made of sarkanda as these form part of the bride's dowry and are highly decorated with colourful fabric and yarns and embellished with bead and shell tassels

These world famous wooden toys and carvings, dating back to the beginning of the 20th century, are produced at Channapatna, a small town near Bangalore in Karnataka. The lacquerware toys and dolls are made in different colours and are greatly appreciated by people both in India and abroad. The raw material is “hale”, a very soft and lightweight wood which is grown near Channapatna. About a century ago, there were very few types of lacquerware products and these had a crude finish. Later, the craft was refined and improved with the use of a metal turned lathe which produced lacquerware products with distinctive brightness by substituting lithopone for sulphur in the manufacture of colour.

Charakku, the king of vessels, is one of the largest cooking vessels to be cast by man. It is made of bell-metal, an alloy of copper and tin, and has a most attractive surface with an old gold tint that does not tarnish and needs no tinning. The moosaris, one of the six categories of kammalas, are the traditional metalsmiths of Charakku. They trace their origin to Vishwakarma, the deity of all craftspeople. They use the cire perdue or lost wax method of casting. Elaborate rituals and the propitiation of the gods traditionally accompany the casting. These high cauldrons/charakkus have a diameter of almost five feet and are wide and shallow. They have handles on either side for ease of lifting. These vessels are used on ceremonial occasions to prepare payasam in large quantities. The process of making the clay mould is so elaborate and laborious and the outcome of the solid metal mould so dependent on precise and careful handling of both the mould and the molten metal that special prayers and rituals are conducted to ensure a perfect result. Smaller items like lamps and small vessels are also crafted by the artisans.

This is an ancient craft - chariots have been used for ritual processions during many of the festivals that are celebrated with great fervour and intensity in Nepal. These include, among others, the Janabala dyo procession in March, the Bsket Jatra in April, and the Rato Machendranath Jatra in May.

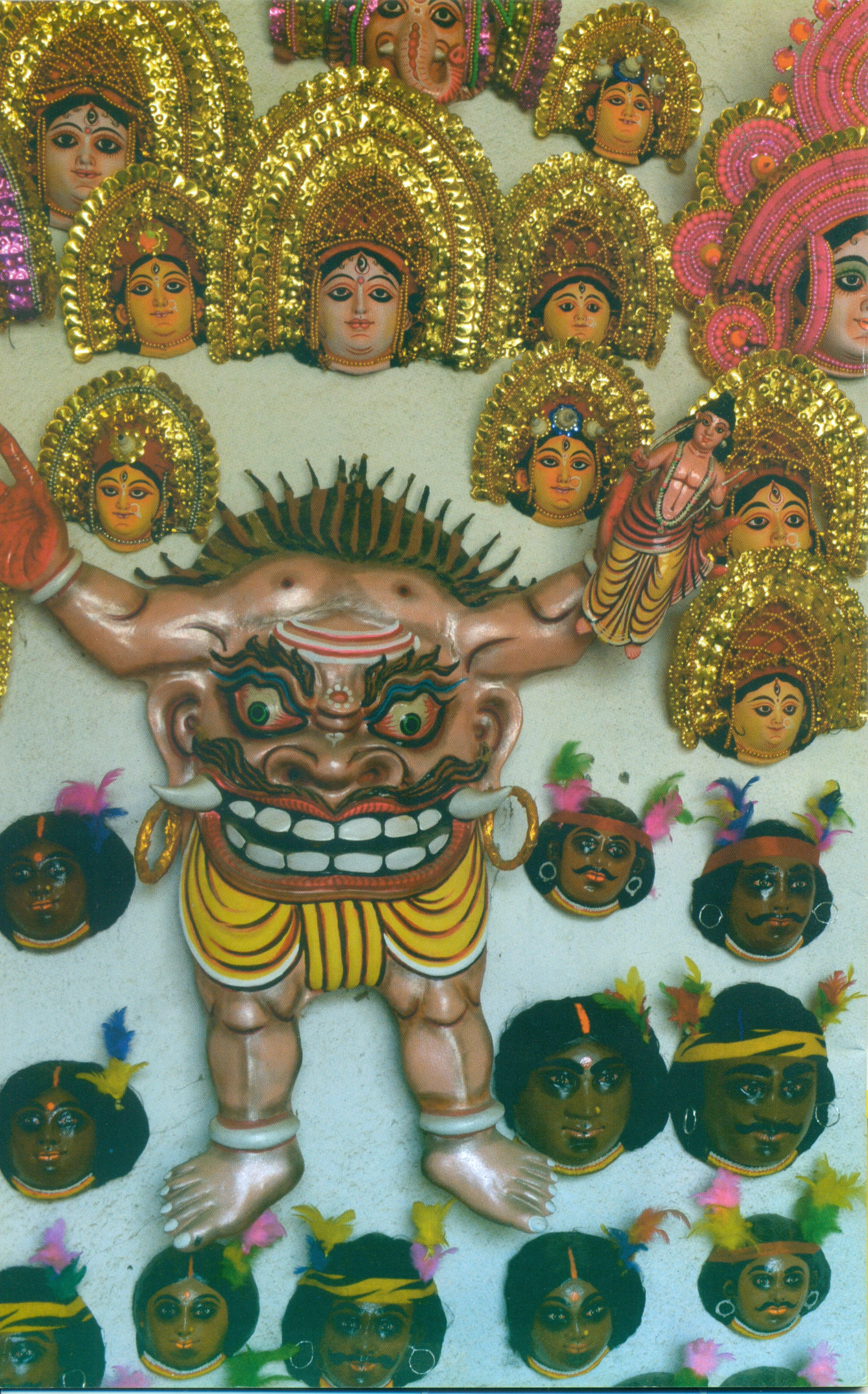

The art of Chau mask making is around 150 years old. This began during the reign of King Madan Mohan Singh Deo of Baghmundi in Charida district of Purulia, West Bengal. These masks were used in Chau dance, which is a martial art and involves vigorous movements. Charida village home to chau mask makers is in Purulia district which is a part of Chota Nagpur Plateau. Making of Chau Masks: Paper pulp and clay are used for making these masks. The materials of making masks are collected locally. Adornments are done with feathers and beads. Tools like Thapi, a small wooden tool is used fro finishing and brushes are used for colouring the masks. The masks are elaborate and and ornamental. They usually depict mythological figures like goddess Durga, Ganesh and demons. They also depict lions, tigers, deers, monkey, peacock etc. Today these masks are made in small size to be used as home souvenirs and decorative objects.

Chendamangalam is a village of handloom weavers in the Ernakulam district of Kerala. The basic raw materials used for the weaving of Chendamangalam Dhoties are a fine count cotton yarn and “kasavu” (zari).The speciality of the dhoti lies in preparation of the warp threads through street sizing. After sizing, the warp threads become almost round and uniform in shape, giving the dhoti a very clean surface without any protruding fibres on it. Borders are patterned with “kasavu”(zari).