JOURNAL ARCHIVE

|

A debate has always existed about the role of museums in the representation of traditional art and craft. There are those that think museums detach craft from its true functionality, placing it behind glass casings and removing it from the grasp of the viewer. And there are those that view museums as preservers of crafts that are dying off in our modernizing world. Of course there are museums that have dealt sensitively with these issues in innovative manners like the Fuller Craft Museum in Massachusetts. However, in spite of these initiatives, most museums either artificially elevate craft into the same category as fine art or depreciate it as a mere cultural artifact. So when I recently visited the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City, I was pleasantly surprised to find a careful balance that presented craft as functional, beautiful and valuable. The Rubin Museum of Art (RMA), located in a historic building in Chelsea NYC, is less than a year old yet boasts one of the largest and most in depth collection of Himalayan art in the world. With a focus purely on Himalayan art from the mountain regions of India, Pakistan, southwest China, Nepal, Bhutan and Burma, the RMA displays paintings, sculptures and textiles from the 12th through the 19th centuries. As a new frontier of art exploration, the RMA believes that Himalayan art can offer American viewers the opportunity to investigate the sacred, political and personal histories contained within. The RMA's mission statement highlights both preservation and documentation of their permanent collection while also focusing on connecting people with art through exhibits and educational programs. Their collection is described as containing "images of historical personages…stories told in lively paintings…sacred teachings, natural events, and calamities…personified in forms moving freely between experience and imagination." Shelley and Donald Rubin were the original collectors behind the permanent collection and the RMA was birthed out of their vision to share this art with people and make it available and accessible to all. Through a variety of initiatives the RMA has already made a name for itself since its October 2004 opening. Rotating and permanent exhibits are curated to entice both scholars and new comers to Himalayan art, providing a wide spectrum of religious, personal and historical pieces. There is also two Explore Art galleries which explain the details and uses of some of the paintings and sculptures in the galleries. This unique aspect of the RMA assists in the balancing act I mentioned above. By adding valuable explanation, the mandalas and bronze Buddhas re-absorb their functionally and authenticity. The RMA also offers educational and other programs for children and adults that further explain the uses and meanings of Himalayan art. More information about the Rubin Museum of Art can be found on their website-www.rmanyc.org |

Issue #009, 2022 ISSN: 2581- 9410 The black bead Mangala-Sutra, the auspicious cord, worn by Hindu women across India is the instantly recognisable symbol of wedded status.Presented by the groom’s family to the bride at the wedding ceremony it’s wearing symbolises the unbreakable nuptial vow and the blessings for a long and content union. The tradition and symbolism of the Mangla-Sutra is as strong today as it has ever been for this talismanic shield remains a powerful assurance of marital bliss, an effective protection from the evil eye andonce donned it is never to be taken off through all the years of wedlock. And while its designs are becoming more contemporary and patterns vary depending on custom and region the one thing that remains the same in this propitious safeguard is that it is strung together with tiny glass black beads. Across the sub-continent black markings have been regarded as carrying potent talismanic protection and the use of black beads extends beyond the Mangla-Sutra to cross beliefs, age and gender as a nazariya literally a deflection of the evil eye. Yet unbeknownst to the vast number of wearers the black beads that were once the tiniest handmade glass beads in the entire world have been replaced by plastic or machine made beads. A cursory online search has over 8 million results for Mangala-Sutrasand over 1 million for Nazariyas each search describing the uniqueness of design and the beauty of its embellishment - none mentioned the material or quality of the black seed-bead used. This act of subtle substitution has led to the death of an ancient globally renowned tradition of hand-crafting the tiniest minutest seed-bead in the world. The incalculable consequence of this act of substitution has led to a loss not just to the demise of a lineage of makers that extends back to antiquity but of the technology of producing these minute glass seed-beads. Though the history of glass production in India dates back over three millennia with finds unearthed in over 250 sites it has been surmised that bead making technology developed around 1200 BCE. Glass-bead remains have been unearthed in over 180 sites with about 40 sites appearing to be bead making sites. The difference between the glass-bead making centers lay in their process technology with the wound-bead method followed in the North– a technology that continues till today. While centers in the South followed the technology of hand-drawn bead making that produced the famed minute seed-beads. This hand-drawn process was an innovative and scientific leap forward as this technology was in effect amass-production method that revolutionized the process of bead-making. Here molten glass was pulled out in the form of long hollow tubes that were then cut up into the required size. This process increased production quantities and allowing for ease in sizing.Further treatment rounded off the sharp edges and the finished beads were polished and threaded for sale. It was these tiny seed-beads that were in great demand not just in the sub-continent but across the ancient world becoming a major global trade item. Exported for over 1500 years, first by the Arab traders and later by the Portuguese their network extended from Rome to China and to Zanzibar, Tanzania, Kenya and other parts of Africa.Their predominance across the Indo-Pacific sea routes in the 10thc. made them one of the most important items traded in that region. Obviously, an item of great status the drawn-glass beads have been found in royal tombs. In his seminal work “Towards a Social History of Bead makers” Peter Francis Jr. states – “the Indo- Pacific bead, is found in archaeological sites from South Africa to South Korea. For 2000 years. It was the most important trade bead of all times, and perhaps the most ubiquitous trade item - certainly of glass - in the ancient world.” India was the envy of the world and bead-making centers were visited not only by traders but others who studied the technology. While archaeological finds suggests there were several centers where drawn-glass beads were produced, it was dominated by the ancient port and production center in Arikamedu (now in Pondicherry) where the tradition died out by the late 16th. Though many reasons have been ascribed to the decline and downfall of the vast trading network that had been built over the centuries the Indian propensity to share oral knowledge and the migratory predisposition of the artisans had led to the knowledge of making being diffused globally. Evidence thus points to the fact that India exported not only the final product but also the skill and technology of hand-drawn beads. Yet, to fulfill the needs of the sub-continent production continued and the knowledge of making was not lost. The heir of the drawn-glass bead industry of Arikamedu wasthe small village of Papanaidupeta. Located at a distance of 160kms inwards in the Deccan from the original port site Papanaidupeta is in Andhra Pradesh at a distance of about 21 kms. from the temple town of Tirupati. With a total area of 1 sq. km. its ‘fame’ lay in it being the only place in the world that practiced and continues to have the knowledge and skill of the 3000 year old technology of hand-making seed-beads. Although it is hard to estimate when bead production started here its climactic conditions and natural resources made it an ideal site. Its existence as a well-entrenched center of bead production was first recorded by D. Narayan Rao in his ‘Report of the Survey of Cottage Industries’ for the Imperial government of Madras (1927-29). Rao described the hollow glass tubes as ‘small as a needle’ with the ‘glass worked into minute beads’ where ‘the size and thickness of the bead averages from the mustard to a gingely seed.’ This cautionary tale of its decline lay in the fact that while the glass-bead makers here were making and supplying the minute black Mangla Sutra beads among the other beads they were producing they were hidden from the world by a chain of middle-men who never let on where the bead came from. In this veil of secrecy and desire to profit lay the seed of its destruction. It was in the 1990s that the handmade beads were slowly and subtly exchanged for low-priced machine-made beads of plastic and glass. And as retailers were unaware of where the beads came from they were unable to source the beads or directly deal with the makers the decline set in and the last time the glass furnace was lit in Papanaidupeta was 2 years ago. It is thus not just that this technology of producing glass seed-beads with a lineage that extends back to antiquity that is endangered as memory of its production process fades. It is that the minutest glass seed-bead bead in the world linked to living culture and heritage with its continuing significance across India is poised at the edge of being lost. However the technology used in making still exists. The tools, furnaces are all locally made. The spaces are available and the skilled artisans are ready to revive the process. Is someone ready to pick up the gauntlet?

Issue #006, Autumn, 2020 ISSN: 2581- 9410 THE DILEMMA OF EDUCATION FOR ARTISANS The future of traditional craft depends on the children of artisan communities. But, in my view the present drive to send all children to school will ensure the death of all traditional skills – craft, farming, healing, folk arts and other specific knowledge systems that artisanal and village communities hold within. ‘Education,’ as exemplified in the system of which we are all part, and which is institutionalized, structured, instruction-oriented and expert-dependent will make extinct all other ways of knowing. The reason for this, very briefly, is that the process of ‘knowing’ in ‘non-codified knowledge societies’ (instinctual, biological, unselfconscious, relating to senses) is very different from the process of ‘knowing’ in ‘codified knowledge societies’ (memory, text and digital codification). The Place of Crafts in Traditional Societies Not so long ago craft was an integral part of Indian life. Every activity of life was supported by artisan communities- from agriculture to day to day household activities to religious activities. Also from birth to death craft occupied a prominent position. That craft was very different from today’s craft, which has become mere income generation activity. The most important aspect of traditional life was the integration of living, learning and earning Threats to crafts Today, craft faces several threats:

- Neither children of artisans nor any other children are taking to craft, even though there is a growing demand for hand work.

- Raw materials are becoming difficult to get, most often due to wrong government polices.

- New systems of awards and branding instituted by ‘well-wishers’ of craft are destroying the integrity of craft making. The UNESCO seal of excellence, master craftsmen awards, and Craft Mark are all detrimental to the cultural strength of traditional artisan communities.

- Many craft shops run by the government ill-treat artisans by not paying or taking bribes etc.

- The Prime Minister's rojgaar yojana (MNREGA) has in many cases made artisans leave their crafts to do unskilled work.

- Due to disproportionate payment/ respect/ power given to designers, artisans would rather be designers than artisans .

Landscape products by Shri Apputti Chami, a highly skilled master potter with a fine sense ofproportion and aesthetics and his wife Srimati Lakshmi who is constantly assisting him

LEARNING FROM ARTISAN COMMUNITIES

I want to make it clear that my journey into the world of rural artisan communities was not with the intention of ‘developing’ or educating them. I went to them to regain what I had lost in the process of becoming educated. I went to learn from them. My strong feelings were that having escaped ‘education’ and ‘development’ they were still original and authentic and were holding on to a culture and worldview which had sustained them for centuries.

While these interactions helped me distil myself in many ways, they also made me understand the numerous hurdles confronting artisans. From lack of availability of raw materials to the lack of demand for their products, there is a pattern to the problems artisans face. These remain discernible problems and need direct solutions. Some problems are insidious in nature and spring from interventions that come in the guise of ‘helping them.’ I view this as the uprooting of the rooted. ‘Development’ and equally ‘education’ remain the mantra of interventionist agencies. Vital issues related to culture, lifestyle and ethos of artisan communities are completely ignored.

Landscape products by Shri Apputti Chami, a highly skilled master potter with a fine sense ofproportion and aesthetics and his wife Srimati Lakshmi who is constantly assisting him

LEARNING FROM ARTISAN COMMUNITIES

I want to make it clear that my journey into the world of rural artisan communities was not with the intention of ‘developing’ or educating them. I went to them to regain what I had lost in the process of becoming educated. I went to learn from them. My strong feelings were that having escaped ‘education’ and ‘development’ they were still original and authentic and were holding on to a culture and worldview which had sustained them for centuries.

While these interactions helped me distil myself in many ways, they also made me understand the numerous hurdles confronting artisans. From lack of availability of raw materials to the lack of demand for their products, there is a pattern to the problems artisans face. These remain discernible problems and need direct solutions. Some problems are insidious in nature and spring from interventions that come in the guise of ‘helping them.’ I view this as the uprooting of the rooted. ‘Development’ and equally ‘education’ remain the mantra of interventionist agencies. Vital issues related to culture, lifestyle and ethos of artisan communities are completely ignored.

Blackened coil tiles

Blackened coil tiles

Mural by the women pottersusing coils of clay

Mural by the women pottersusing coils of clay

Creeper coil tile-part of a hugemural with different types of creepers

Creeper coil tile-part of a hugemural with different types of creepers

Black and red kitchen pottery using our unique method

THE ARUVACODE INITIATIVE

I ended up in Kerala in 1993, to work with a potters' community in Aruvacode, a tiny hamlet in Nilambur. It became self-evident from the very beginning of my interactions with the community that what was called for was efforts at re-awakening the self-esteem and self-confidence of the community. I made no technological changes to their working process; instead I attempted to initiate a creative process that would impart to them the confidence to face the market. Together we developed hundreds of new designs in terra cotta (www.kumbham.org). These items lend aesthetics to day-to-day utility items in urban living. We developed several products that were suited for landscaping, interiors and murals for modern architecture.

Black and red kitchen pottery using our unique method

THE ARUVACODE INITIATIVE

I ended up in Kerala in 1993, to work with a potters' community in Aruvacode, a tiny hamlet in Nilambur. It became self-evident from the very beginning of my interactions with the community that what was called for was efforts at re-awakening the self-esteem and self-confidence of the community. I made no technological changes to their working process; instead I attempted to initiate a creative process that would impart to them the confidence to face the market. Together we developed hundreds of new designs in terra cotta (www.kumbham.org). These items lend aesthetics to day-to-day utility items in urban living. We developed several products that were suited for landscaping, interiors and murals for modern architecture.

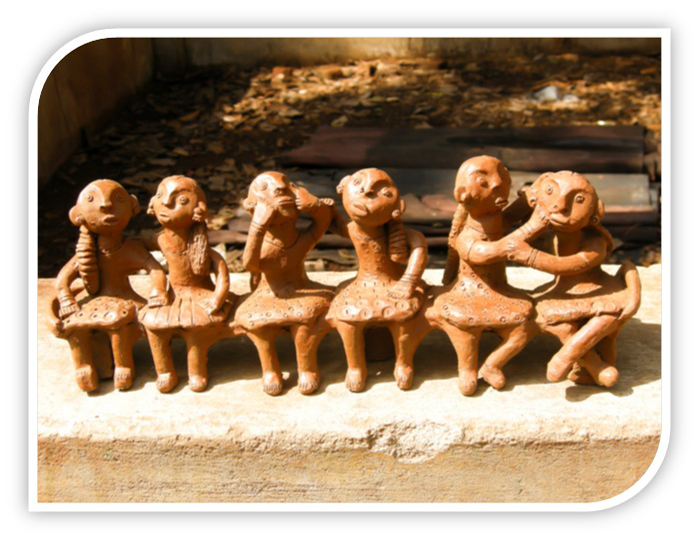

Figurines by 20 year old Srimati Lakshmi who has never been to school

THE DO-NOTHING METHOD

Training (for want of a better word) evolved on the premise that the people in whom we are encouraging creativity are culturally and aesthetically far superior and have greater creative potential than their city counterparts. The Do-Nothing method was founded on the belief that each person is creative and intelligent and therefore the need is only to initiate a process by which the trainees become inspired to use their subdued potential. My efforts to initiate creativity among the artisans proved beyond a doubt that the trainer’s interventions, if at all, need to be restricted to erecting a fence against outside influences that corrupt the genuine aesthetic sensibility of the artisans.

HOW ARTISANS LEARN NATURALLY

The way artisan children learn their respective crafts is as simple as how one learns one’s mother tongue. There is no conscious teaching, no conscious learning, but within three to four years the child learns to speak.

Artisans’ learning process is in fact the learning process practiced by all indigenous communities. How a farmer’s child learns farming or how a traditional vaidya’s child learns their ‘craft’ follow the same process. Observe, immerse, explore experientially (playfulness, play and ‘toy’ making), and imbibe. The child learns without teaching nor conscious learning. The self-organizing system is at work. In fact, in most indigenous languages there is no word for teaching as learning is natural and it happens without any effort.

Traditional artisans’ learning is experientially rooted, learner driven. It has the quality of re-creating, re-inventing and re-living knowledge. In the absence of conscious teaching and teacher, children ‘learn’ from everyone and everything around. Naturally, children of artisans are adept in learning from materials and they learn the craft as though the materials themselves have taught them.

The cognitive conditions ensure the first handedness in these learnings and help learners situate themselves in the cultural conditions of their life.

HOW CHILDREN NATURALLY HAVE THE POTENTIAL OF BECOMING ARTISANS

The cognitive conditions in non-literate cultures are such that every child is a potential artisan. All children are constantly exploring various objects, exploring their materiality, making props for their reenactment of experiences (what modern adults call toys and play). This the perfect foundation for children to acquire the qualities of a true artisan. Of course, now that the school has invaded children’s lives this potential has become rare, and with the general contempt for working with hands, this is becoming even rarer.

Children are able to connect with materials very intuitively. Their instinct guides them to respond to materials and situations and their bodies then learn properties and possibilities of materials experientially. This is true of all children. Why do children bounce while sitting on a sofa? Isn’t this a behavior that can be seen in children all over the world? Why are all children responding in the same manner? They are equipped to make sense of the world around them autonomously.

The knowhow resides in the body and the learner imbibes the movements of the older generation. Instructions and information have hardly any role in the traditional system.

THE CONFLICT BETWEEN TWO PARADIGMS- TRADITIONAL CRAFT LEARNING AND THE MODERN EDUCATIONAL CONTEXT

The Paradigms of the process of learning among artisan communities and in modern institutions are very different. One is a holistic process in which learning happens in the act of living itself without much effort from the learner nor any conscious teaching by the one who knows, whereas in modern institutions the process is fragmented, hierarchy is established by the act of teaching, and both teacher and learner put in extra effort.

So, a curriculum for artisans developed within the framework of the modern educational paradigm would be even more problematic as the very terms of reference are so different. In the indigenous system, materials more or less dictate the process to be adopted in order to work with them, and more importantly the sense of beauty is derived from the characteristics of the material and the process of engagement itself. The indigenous system is about alignment of the inherent potential in humans with the potential in materials. Modern education approaches all this from the point of view of filling the deficit.

The fundamental difference between modern education and traditional learning is that modern education starts with the ‘known,’ a readymade curriculum and a very systematic method segregated from life, whereas the artisan way of learning happens in the midst of life and the realm of the ‘unknown.’

So, what would the blueprint for an artisan curriculum look like? And what should it not be?

Craft intervention from ‘experts’ stresses don’ts. The artisan is becoming a laborer instead of being creative due to insensitive intervention from design experts. First and foremost, an appropriate education must create an environment for learning which is not merely physical but also psychological. Re-creating the condition of the ‘unknown’ is very crucial for awakening the inherent qualities in the learner. The difficulty in this would be that what was very natural needs to be recreated artificially and yet the artificiality needs to be hidden very carefully. The artisan must feel that there is someone to teach him, but no teaching should take place. This would retain authenticity and help the artisan to produce within the parameters of his cultural context.

The ‘Do Nothing’ method I used in working with traditional potters in Aruvacode from 1993 was a very good attempt in teaching without teaching or enabling learning without teaching. Here, the mistake I made was that I did not pretend to teach, and this created confusion among the artisans as to why I was there in the first place.

POTENTIAL OF DESIGN EDUCATION AMBIANCE FOR ESTABLISHING A LEARNING SPACE FOR ARTISANS

Among mainstream institutions only design education has the potential to come anywhere near the natural learning process, provided it is re-imagined consciously by learning from children’s and artisans’ learning processes.

Design education is fundamentally practice based and deals with materials and processes; development of aesthetic sense is part of the curriculum, and it is socially situated and deals with real problems.

This is where one could look for guidance in order to create a curriculum for artisans. But unlike the designer the artisan learns from the material directly. It is the material that guides the process as well as the aesthetic sensibility, which is the result of childhood rooting into their context.

So in in developing a curriculum, there can be mutual learning.

CURRICULUM BLUEPRINT - CONTENT AND CONDITIONS

A two-way strategy is required to address the continuation of crafts. One is to develop a system for the ‘upgradation’ of various skills related to understanding the market etc for the practicing artisan, and the other is for the children of artisans.

Craft Design School for Artisans’ Children

Because the conventional paradigm of education threatens all other ways of knowing, it is important to innovate and re-imagine a learning space for the continuation of crafts.

Rural Design Schools would be meant for children of artisans either as separate from the regular schools or integrated within them, so that artisans feel that what they do is worth learning and thus children practice crafts. Other aspects of traditional knowledge can also be included in these schools.

School for Practicing Artisans

The ‘School for practicing Artisans’ would be based on a vision of development in which artisans are once more connected to all stages of the craft process, part of a broader community that links suppliers, artisans, and buyers. The main aspect of this lies in exposing them to the modern urban craft situation.

There is no institutionalized mechanism in the country to enable artisans to upgrade or contemporize themselves. The artisan is made to depend on designers and managers, whose intervention is making crafts more homogenized. The modern development model of India has transformed its traditional craft economy, positioning local artisans as little more than labour for entrepreneurs, designers and middlemen. While many traditional artifacts have lost their utilitarian relevance and competitiveness at the local level, they have simultaneously become the bearers of cultural and ethical values. By giving rural artisan communities exposure to modern clients' tastes, the project will develop artisans' entrepreneurial, design, marketing and digital skills. This will allow them to take part in the emerging market for eco-friendly, socially just and culturally rich products.

Where and by whom?

More than the curriculum, location and administration of the program are important. If the institutions are placed within the context of their respective communities, children will be able to experience craft directly, and without much effort the transfer of knowledge will take place.

The people responsible for the centre have to have deep respect for the abilities of artisans and must treat them with respect at all levels.

In some sense, a very sensitive fencing is required so that artisans don’t feel inferior and start mindlessly imitating what is happening around them. So, the intervention must focus on creating self-respect in artisans, and encouraging the ability to create authentic products, the ability to solve problems etc

LESSONS FROM TRADITIONAL CRAFTS

There is more to learn from the knowledge paradigm of traditional artisans that can address the crisis of modern education at all levels. One can start with design education and then look at the total modern educational paradigm staring from children and going all the way to higher education.

The biggest crisis in school education is that fundamental values that are natural to children are being destroyed, values like dedication to work or learning, involvement, creativity, self-initiative and quest for knowledge, development of skills and even real values of love, care, co-operation etc.

Apart from obvious aspects in their lives such as sustainability, artisans offer lessons in the formation of values and attitudes towards work, the learning process, knowledge, skills and learning conditions etc.

The biggest advantage of tradition has been that living, learning and livelihood are integrated and hence it is rooted in experience. Every moment is a learning moment. The child engages with knowledge right from the womb, as pregnant women in traditional societies continue to work even till the ninth month.

The child is constantly immersed in an environment of knowledge creation yet hardly ever encounters teaching or instruction. All this happens in an environment of freedom and care so that the autonomy of the child is at work. The self is given importance without developing the ego.

Figurines by 20 year old Srimati Lakshmi who has never been to school

THE DO-NOTHING METHOD

Training (for want of a better word) evolved on the premise that the people in whom we are encouraging creativity are culturally and aesthetically far superior and have greater creative potential than their city counterparts. The Do-Nothing method was founded on the belief that each person is creative and intelligent and therefore the need is only to initiate a process by which the trainees become inspired to use their subdued potential. My efforts to initiate creativity among the artisans proved beyond a doubt that the trainer’s interventions, if at all, need to be restricted to erecting a fence against outside influences that corrupt the genuine aesthetic sensibility of the artisans.

HOW ARTISANS LEARN NATURALLY

The way artisan children learn their respective crafts is as simple as how one learns one’s mother tongue. There is no conscious teaching, no conscious learning, but within three to four years the child learns to speak.

Artisans’ learning process is in fact the learning process practiced by all indigenous communities. How a farmer’s child learns farming or how a traditional vaidya’s child learns their ‘craft’ follow the same process. Observe, immerse, explore experientially (playfulness, play and ‘toy’ making), and imbibe. The child learns without teaching nor conscious learning. The self-organizing system is at work. In fact, in most indigenous languages there is no word for teaching as learning is natural and it happens without any effort.

Traditional artisans’ learning is experientially rooted, learner driven. It has the quality of re-creating, re-inventing and re-living knowledge. In the absence of conscious teaching and teacher, children ‘learn’ from everyone and everything around. Naturally, children of artisans are adept in learning from materials and they learn the craft as though the materials themselves have taught them.

The cognitive conditions ensure the first handedness in these learnings and help learners situate themselves in the cultural conditions of their life.

HOW CHILDREN NATURALLY HAVE THE POTENTIAL OF BECOMING ARTISANS

The cognitive conditions in non-literate cultures are such that every child is a potential artisan. All children are constantly exploring various objects, exploring their materiality, making props for their reenactment of experiences (what modern adults call toys and play). This the perfect foundation for children to acquire the qualities of a true artisan. Of course, now that the school has invaded children’s lives this potential has become rare, and with the general contempt for working with hands, this is becoming even rarer.

Children are able to connect with materials very intuitively. Their instinct guides them to respond to materials and situations and their bodies then learn properties and possibilities of materials experientially. This is true of all children. Why do children bounce while sitting on a sofa? Isn’t this a behavior that can be seen in children all over the world? Why are all children responding in the same manner? They are equipped to make sense of the world around them autonomously.

The knowhow resides in the body and the learner imbibes the movements of the older generation. Instructions and information have hardly any role in the traditional system.

THE CONFLICT BETWEEN TWO PARADIGMS- TRADITIONAL CRAFT LEARNING AND THE MODERN EDUCATIONAL CONTEXT

The Paradigms of the process of learning among artisan communities and in modern institutions are very different. One is a holistic process in which learning happens in the act of living itself without much effort from the learner nor any conscious teaching by the one who knows, whereas in modern institutions the process is fragmented, hierarchy is established by the act of teaching, and both teacher and learner put in extra effort.

So, a curriculum for artisans developed within the framework of the modern educational paradigm would be even more problematic as the very terms of reference are so different. In the indigenous system, materials more or less dictate the process to be adopted in order to work with them, and more importantly the sense of beauty is derived from the characteristics of the material and the process of engagement itself. The indigenous system is about alignment of the inherent potential in humans with the potential in materials. Modern education approaches all this from the point of view of filling the deficit.

The fundamental difference between modern education and traditional learning is that modern education starts with the ‘known,’ a readymade curriculum and a very systematic method segregated from life, whereas the artisan way of learning happens in the midst of life and the realm of the ‘unknown.’

So, what would the blueprint for an artisan curriculum look like? And what should it not be?

Craft intervention from ‘experts’ stresses don’ts. The artisan is becoming a laborer instead of being creative due to insensitive intervention from design experts. First and foremost, an appropriate education must create an environment for learning which is not merely physical but also psychological. Re-creating the condition of the ‘unknown’ is very crucial for awakening the inherent qualities in the learner. The difficulty in this would be that what was very natural needs to be recreated artificially and yet the artificiality needs to be hidden very carefully. The artisan must feel that there is someone to teach him, but no teaching should take place. This would retain authenticity and help the artisan to produce within the parameters of his cultural context.

The ‘Do Nothing’ method I used in working with traditional potters in Aruvacode from 1993 was a very good attempt in teaching without teaching or enabling learning without teaching. Here, the mistake I made was that I did not pretend to teach, and this created confusion among the artisans as to why I was there in the first place.

POTENTIAL OF DESIGN EDUCATION AMBIANCE FOR ESTABLISHING A LEARNING SPACE FOR ARTISANS

Among mainstream institutions only design education has the potential to come anywhere near the natural learning process, provided it is re-imagined consciously by learning from children’s and artisans’ learning processes.

Design education is fundamentally practice based and deals with materials and processes; development of aesthetic sense is part of the curriculum, and it is socially situated and deals with real problems.

This is where one could look for guidance in order to create a curriculum for artisans. But unlike the designer the artisan learns from the material directly. It is the material that guides the process as well as the aesthetic sensibility, which is the result of childhood rooting into their context.

So in in developing a curriculum, there can be mutual learning.

CURRICULUM BLUEPRINT - CONTENT AND CONDITIONS

A two-way strategy is required to address the continuation of crafts. One is to develop a system for the ‘upgradation’ of various skills related to understanding the market etc for the practicing artisan, and the other is for the children of artisans.

Craft Design School for Artisans’ Children

Because the conventional paradigm of education threatens all other ways of knowing, it is important to innovate and re-imagine a learning space for the continuation of crafts.

Rural Design Schools would be meant for children of artisans either as separate from the regular schools or integrated within them, so that artisans feel that what they do is worth learning and thus children practice crafts. Other aspects of traditional knowledge can also be included in these schools.

School for Practicing Artisans

The ‘School for practicing Artisans’ would be based on a vision of development in which artisans are once more connected to all stages of the craft process, part of a broader community that links suppliers, artisans, and buyers. The main aspect of this lies in exposing them to the modern urban craft situation.

There is no institutionalized mechanism in the country to enable artisans to upgrade or contemporize themselves. The artisan is made to depend on designers and managers, whose intervention is making crafts more homogenized. The modern development model of India has transformed its traditional craft economy, positioning local artisans as little more than labour for entrepreneurs, designers and middlemen. While many traditional artifacts have lost their utilitarian relevance and competitiveness at the local level, they have simultaneously become the bearers of cultural and ethical values. By giving rural artisan communities exposure to modern clients' tastes, the project will develop artisans' entrepreneurial, design, marketing and digital skills. This will allow them to take part in the emerging market for eco-friendly, socially just and culturally rich products.

Where and by whom?

More than the curriculum, location and administration of the program are important. If the institutions are placed within the context of their respective communities, children will be able to experience craft directly, and without much effort the transfer of knowledge will take place.

The people responsible for the centre have to have deep respect for the abilities of artisans and must treat them with respect at all levels.

In some sense, a very sensitive fencing is required so that artisans don’t feel inferior and start mindlessly imitating what is happening around them. So, the intervention must focus on creating self-respect in artisans, and encouraging the ability to create authentic products, the ability to solve problems etc

LESSONS FROM TRADITIONAL CRAFTS

There is more to learn from the knowledge paradigm of traditional artisans that can address the crisis of modern education at all levels. One can start with design education and then look at the total modern educational paradigm staring from children and going all the way to higher education.

The biggest crisis in school education is that fundamental values that are natural to children are being destroyed, values like dedication to work or learning, involvement, creativity, self-initiative and quest for knowledge, development of skills and even real values of love, care, co-operation etc.

Apart from obvious aspects in their lives such as sustainability, artisans offer lessons in the formation of values and attitudes towards work, the learning process, knowledge, skills and learning conditions etc.

The biggest advantage of tradition has been that living, learning and livelihood are integrated and hence it is rooted in experience. Every moment is a learning moment. The child engages with knowledge right from the womb, as pregnant women in traditional societies continue to work even till the ninth month.

The child is constantly immersed in an environment of knowledge creation yet hardly ever encounters teaching or instruction. All this happens in an environment of freedom and care so that the autonomy of the child is at work. The self is given importance without developing the ego.

Banyan tree mural 10 feet height–This was the first mural done in 1997 at Hotel Pankaj, Trivandrum.

Banyan tree mural 10 feet height–This was the first mural done in 1997 at Hotel Pankaj, Trivandrum.

Private collection Size 8 feet by 10 feet. The potters were trying out a new technique of using colorto define the shape

In today’s technological world, learning from people considered backward will be a challenge. The real damage of education is the installation of superiority over our natural tendency for humility and openness. It is the educated elite who have to do the unlearning that is required to renew our respect for the rich cultural offerings of traditional communities. This is an arduous, long process.

All photos by Jinan K.B.

Private collection Size 8 feet by 10 feet. The potters were trying out a new technique of using colorto define the shape

In today’s technological world, learning from people considered backward will be a challenge. The real damage of education is the installation of superiority over our natural tendency for humility and openness. It is the educated elite who have to do the unlearning that is required to renew our respect for the rich cultural offerings of traditional communities. This is an arduous, long process.

All photos by Jinan K.B.

The female octopus is born, grows to maturity, gives birth to her clutch of children, and promptly dies. I often think it must be wonderful to have ones role in life, its purpose and parameters, so clearly defined. I, on the other hand, for the last fourteen years in DASTKAR have straddled, often uneasily, the twin roles of designer and development person.Working in the field of traditional craft, the two are not always synonymous, though design can lead to development, and development should be designed. There is a conflict both of function and responsibility. Whose creativity are you to express, your own or the craftsperson's? Who is your client - the consumer, who wants an unusual and exciting product at the most competitive price; or the craftsperson - who needs a market for his product as similar to his traditional one as possible, so that it does not need constant alien design interventions, or conflict with the social, aesthetic and cultural roots from which it has sprung. Those of us who have gone through a formal art or design education have been taught to realise our own creative imagination to the full, and given the technical expertise and tools to do so. Working with craftspeople, one has to dampen ones own creative flame in order to light the craftsperson's fire. One must push, not pull..... The purpose of ones sample design range is to inspire craftspeople to do their own further innovation, not stun them into passive replication. They must be taught to use their minds and imagination as well as their hands.Craftspeople must be involved in every aspect of design and production and understand the usage of the product they are making. The interventionary voluntary agency or designer must also understand and study the craft, the product and the market they are trying to enter.Often there is a perception of organisations like the Crafts Councils and DASTKAR as arty-farty ladies obsessed with design. This obsession is seen as revealing our inherent superficiality and inability to think in truly "developmental" "issue-based" terms. Just as craft itself is rejected as a viable economic activity by those marching into the 21st Century to newer, more technological tunes. But artisans still make up 23 million of our working population; and to talk about the craft sector as a means to sustainable employment, without talking of design is like talking about the issue of the Child without talking of education.Crafts producers cannot be economically viable unless their product is marketable. The product can only be marketable if it is attractive to the consumer. i.e. if the traditional skill is adapted and "designed" to suit contemporary consumer tastes and needs. Design does not mean making pretty patterns. It is matching a technique with a function.All over India women are being taught to sew, embroider, appliqué, crotchet, knit and tat, with the bait of becoming economically independent. Almost always the second object they are taught to make (the first is a cushion cover!) is a tea-cosy, regardless of the fact that less and less Indian homes use tea-cosies. The shape is always wrong (is it a bolster cover or a dunce-cap?) because the craftswomen do not understand the usage, and have never been shown a teapot. Similarly, table mats are always made with the decorative motif squarely in the middle of the mat, because no one has explained that is precisely the area that is covered by the plate, and therefore can (and should!) remain unadorned.We should not be embarrassed or defensive about an emphasis on product design and marketing as the catalyst and entry point for development in the craft sector. The overwhelming demand for these services from craftspeople all over the country, and the disastrous results when supposed Income Generating Projects are left to flounder without guidance, should answer any doubts about the superficiality of this approach, or whether it is required. A recent survey of one of the craft producer groups we work with in Bihar showed the importance of an integrated approach to craft development and marketing. Sales generated through six DASTKAR exhibitions and Bazaars for which they were assisted with product design, raw material identification, production and quality control guidance were over 3 lakhs, as opposed to a total of less than 1 lakh at seven other Bazaars (including the CAPART Mela!) over the same period, selling their standard products.Why do craftspeople with centuries of a skilled tradition need these outside interventions at all is a question frequently raised. Looking at the distortions and deterioration caused by so many interventions, however well intentioned, does give one pause. But tradition must be a springboard not a cage. Craft, if it is to be utility-based and economically viable, cannot be static. It must respond to changes of markets, consumer needs, fashion and usage. It is the role of the designer and product developer to sensitively interpret these changes to craftspeople who are physically removed from their new marketplaces. In Ancient India, every individual had an implicitly defined role in society, ordained by birth. Craftsmanship was a heritage, tempered by years of arduous apprenticeship in chhandomaya (the rules of rhythm, balance, proportion, harmony and skill), controlled and protected by the structure and laws of the guild. In the guild the master craftsman, the raw apprentice and the skilled but uninspired jobsman all had a place and purpose. (Today’s craftsperson has to be all things in one, including his own entrepreneur.) The craftsman had the status of an artist. As a member of a society with strict rules and hierarchies, both within his guild and the outside world, he and his products were protected, and their quality and traditional continuity controlled. Customers were close at hand, their lifestyles not too markedly different from his. Whether his skills provided simple village wares or jewelled artifacts for the temple, it was a supportive interdependence based on a mutual need, understanding and appreciation. The craftsperson was his own designer, and the embellishments came only after the shape was perfected to the function. The aesthetic and the practical blended in a natural rather than artificially imposed harmony. Today most craftspeople, practicing traditional skills but vying with machines, speeded up deadlines and 'craze for forrun' fashions, no longer protected by guilds or the enlightened, hands-on patronage of court or temple, are increasingly faced with the problems of diminishing orders and the debasement of their craft. They are making products for lifestyles remote from their own, and selling them in alien and highly competitive markets. Their own lives and tastes have suffered major transformations - alienating them further from their skills and products. A traditional juthi-maker may still embroider gold peacocks onto a pair of shoes whose turned up toes echo the ends of his moustache, but he himself will probably be wearing pink plastic sandals! An alabaster Buddha will have a red bulb and electric flex spawning out of its belly in a mad attempt to contemporise it into a bedside lamp. Consequently, craft has degenerated today from a stunning ritual object of worship to bric-a-brac that sells on the pavement for Rs. 10.00. Though many Government and non-Government agencies have discovered traditional craft as a vehicle for income generation, its usage has not always been accompanied by a sensitivity to the needs of the craftsman and the consumer, or an analysis of the market. And, as the tourist and export demand for instant "ethnic" has grown, middlemen and traders, many of them ignorant and exploitative, have also jumped onto the bandwagon of craft production and sale. This has resulted in many of the more intricate and unusual forms and skills being abandoned, with the quick production of a cheap product being the priority. Motifs, techniques, stitches and usages distinctive to particular communities and areas have been merged and muddled together. The everyday utilitarian crafts have suffered too; bypassed in favour of more eye-catching, ornamental ones. The cheap, tacky looking yoke pieces, skirts and patches sold on the Janpath sidewalks and at the Surajkund mela under the generic brand name of "mirrorwork" and "Kutchi bharat" bear little relation to the extraordinary embroideries various Kutchi communities make for themselves, or their potential for further development. This is not just aesthetic disaster, but bad economics as well. Thousands of women with high-level skills and earning power are reduced to breaking stones for a living, while the antique pieces their grandmothers made sell in the Sunder Nagar boutiques for a fortune. At a CCI Seminar on crafts in 1991, Reema Nanavaty recalled the inception of SEWA's project in drought-ridden Banaskantha, "But even before water, the major problem of the women was work. Whenever you talk to the women, the first thing they ask about is work. Everything else is secondary." Today the old embroideries they were selling off their backs are the design inspiration for contemporary garments that earn the craftswomen incomes of Rs. 1000 to 1200 a month. People often say, why don't Indian craftspeople simply make the same beautiful things they used to? The reason for this is so obvious we have literally been blinded by it. Craftspeople cannot afford to keep samples and so have never seen what their forefathers used to make. Craftspeople's data banks are in their minds and fingertips but, if you paint Mickey Mouse to order often enough on a papier-mache box instead of a Mughal rose, eventually the memory of the rose will fade away. The irony is that it is we who are fortunate enough to acquire the beautiful objects that are their heritage; we who have access to museum collections and reference books. It is we, therefore, who must be aware of and sensitively interpret a craftsperson's tradition to him. This is our responsibility. A craftsperson does not have the confidence to say "no". He needs the order too much. As a result we have all turned into instant "designers" - often, alas, without introspection or homework. A bored housewife clips a cross stitch motif of be-ribboned kittens out of WOMAN & HOME and turns it into a kantha sari pallav; an exporter (too dependent on air-conditioning to trek out to Saurashtra) gives a patchwork toran to be replicated in Trans-Jumna - and adds a dash of Punjabi phulkari embroidery just for fun. Instead of re-interpreting the legendary skills of Kerala wood carvers to make new furniture, a glass sheet is perched on the top of antique boat prows or a truncated pillar to awkwardly transform them into a table. Nor are good ideas and good intentions alone enough to guarantee the desired results. Some years ago a funding agency commissioned a talented young designer to do a design project for an NGO working with tussar weavers. She developed a stunning range of high fashion Western garments which were show-cased at a high-profile exhibition in Delhi. But the producer group - tribal women who were part of a Gandhian Ashram in the depths of rural Bihar - were unable to fulfill the orders as they didn't have the requisite tailoring skills (the original sample range had been made by a friendly exporter in Noida) and the whole exercise, (and an investment of over 4 lakhs) was a disaster. The Ashram women trailed around for years to Melas and Bazaars trying to discount-sale the stock piles of unsold samples, all now out of date, crumpled and shop-soiled, and finally the IGP programme folded up altogether. The means and the ends, the design and the beneficiary, must meld and match together. Only then can long-term objectives be met. The motifs and usage’s of a craft tradition cannot and should not remain static. But changing them requires knowledge, sensitivity and care. NID designers, often slanged by the development world as being too rarefied and impractical, have achieved some significant successes in projects for Jawaja, Gurjari and Urmul, and in the North East, where their input has been long-term and sustained; and the NID student craft documentations are a invaluable reference source. An essential tool in craft development is that motifs, designs and techniques be documented and accessible. DASTKAR's project with Madhubani painters in North Bihar - one of the poorest, most backward parts of India - was an example of changing the function, changing the design and finding an appropriate though radically different usage for a traditional craft through the process of documenting its motif tradition. Discovered in the 60's, the votive paintings of Mithila, transferred from village walls to handmade paper, were an instant artistic craze. The paintings rapidly became something of an interior decoration cliché in contemporary urban Indian homes looking for an "ethnic" identity. Village women of all levels of skill and artistry were persuaded by eager traders and exporters to abandon their sickles for the brush. Inevitably there was a surfeit, and then a hiatus in the market. By the 80's, Madhubani painting as a marketable commodity was dead. You cannot, however, tell women who have tasted economic independence to go back to painting their walls. New ways of tapping this creative source needed to be found. DASTKAR felt the decorative motifs, the floral borders, the peacocks and parrots, the interlocking stars and circles, that embellished the Kohbar, encircling the Gods and knitting them into their cosmic patterns, were in themselves a rich directory of design motifs and decorative elements that could be used on products of daily usage and wear. Sarees, dupattas, soft furnishings, are by their function, less subject to the vagaries and shifts of consumer fad. The transition from iconographic art to functional craft need not be crass or commercial, if sensitively done. Not by gods and goddesses being transferred blindly by the hundred to cushion covers, but by women being taught to use their own artistic instincts in new ways. More dramatic, more spontaneous, more personally creative, I think, in many ways than an invocatory Kohbar being painted for money and hung mindlessly on a restaurant wall. In the devastation that followed the 1989 earthquake it was those women in North Bihar who were wage earners through craft who were able to sustain and succour not only their own families, but those of other less fortunate villages. That same strength today, gives them the power to say no to social practices or religious taboos that aim to victimize them. A craft designer, (whose ultimate objective is the coordinated development and self sufficiency of the craftsperson rather than herself) must keep in mind the existing skill levels of her target group. The designer must not just work with one or two master craftspersons. The sample range will be wonderful but production a disaster. She must project her initial designs to available skill levels, and use successive sampling workshops to gradually upgrade skills and design sensibilities. In the DASTKAR Ranthambhore project, working with almost unskilled women - their hands more used to wielding the scythe than the needle - the first patchwork range was made up of 6 inch squares and strips in very basic permutations. Vivid and unusual combinations of colours and prints disguised the crudity of stitchery and simplicity of design. They sold well, as do the much more complex designs of tiny triangles, hexagonals and stars in subtle colourways the women have gradually been trained to do in the intervening five years. Creating a simple but effective design, using a small budget and limited resources, is an exciting test of a designers skill. Seeing the growth and confidence of a newly emerging crafts community successfully selling products they have made themselves for the first time, using skills they never knew they had, is even more exciting. There are two cardinal principles:- one, the customer does not buy out of compassion. The product must be competitive in price, in aesthetic, in function, and two: The ultimate skill of the craft designer lies in making herself redundant. SEWA Lucknow is often cited as the NGO success story in using a traditional, almost moribund, skill (chikan embroidery) as a means to a 2 crore turnover and social and economic empowerment for thousands of women. But "design" in that intervention went far beyond the cut of a kurta or the application of a new embroidery buta. It included skill upgradation, the documentation and revival of traditional stitches, embroidery motifs and tailoring techniques, the introduction of new kinds of raw material (ranging from kota to tussar), sizing, costing, quality control and production planning - and an alternative marketing and promotional strategy that would enable a small, broke NGO to compete effectively with the entrenched dalals in the Chowk. The approach and philosophy was always:

- to provide ideas and stimuli for creativity and innovative product design in the craftswomen themselves.

- to explain the rationale behind items developed and guidelines laid down by us.

- to develop a product range that incorporated the different skill levels of all members of the group.

- to keep the product usage and price applicable to widest possible market and consumer.

- to harmoniously incorporate the motifs, techniques and shapes of traditional chikan-kari into completely new products.

Issue 1, Summer 2019 ISSN: 2581 - 9410 The concern on ecological principles is forcing the design fraternity to turn towards more sustainable design solutions. There is a strong reaction against the dehumanizing effects of the Industrial Revolution and consequently, there is an attempt to go back to the traditional skills of design, craftsmanship, and community services (William Morris). The universal trend is shifting its focus from mass industrial products to localized and customized product lines, which are ecologically sustainable. The requirement of ecologically sustainable designed products are directing the universe from globalization to regionalization and further to localization (Shashank Mehta ).Local regional products are gaining recognition and are appreciated in urban and global markets as they are constantly evolving and innovating ways for survival and sustaining under serve constraints. There is tremendous scope for these regional product ideas and traditional knowledge skills to be developed for contemporary applications in India. A sustainable developed methodology for this rural and regional design industry is needed to convert the tradition skills and culture ideas of the specific region into marketable products at the grassroots level. So far, the interventional development programme in this sector is not effective enough because of unstructured and insensitive planning. India has many unexplored regional areas with rich traditional skills waiting to be brought into the main stream of contemporary business. We need to do much more than what has been done or achieved so far. My recent study in Kundera, a small village of Rajasthan gave me an insight and helped me understand a multitude of individuals, families and groups of people perpetuating traditional knowledge based activities of their forbearers. The purpose of my paper is to explore the possibilities of a structured methodology to offer assistance to enthusiastic women artisans of Kundera village of Rajasthan for their empowerment. The study will explore and identify their potential /talent/ aesthetic qualities and their aspiration and try to find the ways to use and apply their potentials and skills to the craft and business practices to gain empowerment .The paper will identify the various possible working segments within the working environment and try to address each issue according to their requirement and then create a structured methodology for implementation. The study investigates the issues of empowerment for the rural artisan from the currently existing and running craft initiative programmes within the country.

Introduction

The Ranthabhore National park in Swai Madhopur District of south east Rajasthan was created to enable the Tigers to live and move freely amidst the flora and fauna that were his traditional birthright, creating this space and freedom, however meant that villages, whose ancestors had for centuries lived within the environ of the park lost their homes and had to be resettled though these villages were settled in the areas outside the park. They lost their access to wood,A Directional Study water, and traditional farming lands. As an initiative to support these villages, Dastkar (NGO) Ranthambore was created with the objective of acting as a catalyst in rebuilding the displaced communities’ social and economic foundations. In the spring of 1989, Dastkar, Ranthambhore took charge of the income generation programme for the villagers particularly women. Today the cooperative has been providing training to about 300 women earning about 26 to 78 euros per month. Business turnover is about Rs 70,000/- per annum and aiming to achieve about a million rupees soon. The craft stores are mushrooming in a great speed all over the country because universal trend is shifting its focus from industrial products to localized and customized product lines, which are ecologically sustainable. There is tremendous scope for these regional product ideas and traditional knowledge skills to be developed for contemporary applications in India. Craft is a significant sector in India, not only because of its intrinsic cultural and aesthetic value but also because of its promising economic development. Handicraft employs more than 9 million people in India and contributes about 1.6 billion Dollars to export earning and 4 billion dollars to domestic earnings but it still reaps fewest benefits from the lucrative markets and even the most talented often live in abject poverty. Although, most artisans are highly skilled but still and have low social status. With the growing demand of handcrafted product, there has been a great pressure to produce more products to cater to the demand, hence more work forces is needs to be created in the present set up of Dastkar Ranthambhore center too, to help economic development in the country. To train more people in craft sector and build capacity in the present set up of Dastkar Ranthambore center for production increase, few near by villages of Ranthambore were visited; where more women artisan could be trained and brought to support the development of indigenous, localized, network.The Problem

It is a shared opinion that the transition towards sustainability is a continuous and articulated learning process, which requires radical changes on multiple levels (social, cultural, institutional and technological). It is also shared that, given the nature and the dimension of those changes, a system discontinuity is needed, and that therefore it is necessary to act on a plan. The challenge now is to understand how it is possible to facilitate and support the introduction and diffusion of such innovations. ( Carlo Vezzoli, Fabrizio Ceschin and René Kemp) The cluster development programme created by the Government of India so far, are mainly related to very few surface areas. Design & technology training under these schemes aims at, up gradation of artisans’ skills without reaching to the core areas of understanding, which in return marginally improves or diversifies the existing product line. Hence sustainability and empowerment still remains questionable. Though, these schemes do help in developing a few new design as prototypes to some extent for the market but since these schemes are of such short duration within limited time and with unstructured approach with randomly selected team of trainers, mostly fall short of expectation of organizers and artisan both. Even the supply of improved/modern equipments to the craft persons during the training programmes to create products under these schemes, does not mean much as the artisans are not gone through a proper structural training to be able to use these equipment to its fullest potential. Further to this, the to lack of intensive market survey prior to these developmental work shops the product which get developed through intervention are not in tuned with the market demand, hence, designed prototypes remain in cold storages as these products fall short of understanding the demand of the market. The promotional sales organized by organizing the Craft bazaar and handicrafts expos to facilitate direct sale of articles produced by the artisan by the government, still remains an unsuccessful venture because of the artisans’ lack of confidence in their own created products due to improper training programmes They usually do not take owner ship and onus of their own initiative and depend on the government or their design trainers. As government run programmes are trying their best to promote craft Industry by providing many government run schemes but the effort is not enough or structured well to cater the demand of handcrafted business. There is a demand of well-structured craft initiative programmes from all the stakeholders in India if one wants the success of this industry.FIELD EXPERIENCE

The Potential and The People

India is known to be culturally rich with rich traditional skills in almost in all the regional areas. Interiors of India are still with no assistance and initiatives from government and NGO’s. Though, there is tremendous scope for these regional product ideas and traditional knowledge skills to be developed for contemporary applications in India. Ranthambhore in Rajasthan showed enough interventional potential. Villagers had lost their homes, and had to be resettled in the areas outside the park loosing their access to farming lands. They did not have any traditional craft practice for their survival but were practicing craft mainly to create their daily requirements. Their source of income was most unpredicted in this scenario they all surviving on hard labor including the women of the village. Experiencing the regional people in their own natural habitat trying to find opportunity in the spectacular skills, unique imagery, and also fast disappearing appreciation for their own inherent traditional skills, all were astonishing facts, which needed reassurance and appreciation to bring them to empowerment. The groups of 30 women artisan from different age groups and economic back ground, who were enthusiastic, eager and passionate to work and learn new skills, belonged to same village from same community. The interaction with these women artisan was satisfying learning experience. It was surprising to find some of these women were reasonably educated and they could read and understand simple instructions. They took the lead during the first interaction and became the interface between their community and us; the mobilizing factor become easy; they could quickly translated the questions into local dialect if some one found it difficult to understand the instruction or questioned asked. The initial interactive conversational sessions mainly revolved around their family responsibilities, their personal problems, their economic front, community restrictions and also family disputes and of course about their aspirations, goal and desire where do they like to see themselves. The interaction and Intervention remained shared and not imposed one in the familiar and friendly environment. The idea was to unwind them completely so that, they are able to freely share their personal inhibitions, discuss freely about their skill potentials and capabilities and talk about problem they foresee in undergoing a training programme or spending their valuable work time with us.Their Awareness and Enthusiasm

The biggest asset with these women artisan was that they all were familiar with Dastkar unit (NGO involved in craft initiative programmes) close to their village and were also aware of those women who are engaged in doing craftwork and business work, like visiting the various Bazaars and selling their products and are economically self-sufficient. They seemed aspired to be like them in similar situation with similar standing in their communities. They wanted to learn all the skills involved in craft business, so that they can earn for themselves and be independent like those women working with Dastkar unit.Skill Potential

Visit to women habitats was to understand them more holistically with their families, neighbors and surroundings to explore and identify artisan’s potential /talent/ aesthetic qualities on an individual base. Auditing their skill level for the training programme became clearer as one could notice, enough hand crafted products lying around in their humble dwellings for their personal use. The homes were simple with a very few items aesthetically arranged according to their sensibilities. Their floor covers were made of used fabric (as to utilize the fabric better and in more sustainable manner) put together aesthetically in some kind of geometric structural pattern. The walls were extremely well decorated, with hand, painted local motifs and with locally available natural colours. The floors were clean with patterns created on mud by using hands. The most interesting product, which the whole community had created individually, was the pot stand. Female of the house is required to fetch the water from near by well. They keep the earthen pots one on the top of other on their head, to balance these pots they put a kind of a ring on their head under the pots, which serves as stand. The entire village community very well constructed applying various handcrafted techniques created this ring individually. The skill audit revealed that there was no dearth of basic skills in the community. Each of them had some kind of skill or the other at different level. Some showed interest in embroidery while other showed interest in sewing or machining. There were other women who were interested in weaving the basket from naturally available grass for their bread. Some showed interest in local motif development for the painting purpose while others showed potential in articulated communication skills. It was motivating enough to realize that the participation of stake holders was at its fullest and there was no dearth of basic talent in the region. Skill mapping and creating inventories of their skill potential, design sensibilities all became important facts to start up the intervention plan.Experiencing The Market for the Available Skill

Experiencing the retail options of crafted products and then trying to balance the market requirement with the skill available of the artisan for manufacturing purposes seemed a focused idea for intervention purpose. Simultaneously visits to understand the regional and metro market within the country for product ideas and product categories to consolidate the intervention process for the artisan, if one wanted to start the intervention soon. A continuous auditing and evaluation of the product along with the journey taken so far in developing the product becomes important steps to keep abreast with the craft intervention for the business purpose.Availability of Regional Resource

Experiencing and understanding the region for natural and industrial material resources, skills availability and other human resources all became important factor for the intervention .The Idea

To develop workable self-managed people centric and independent model for competent business does not remain a Herculean task if crucial needs are satisfied through training and nurturing the required potential of an individual. It was evident after the field experience that the regional women needed empowerment. Traditional hand skills needed to be brought into professional enterprise as an important initiative. Women needed to be encouraged to work in a systemized manner where they can earn sustainable income for their empowerment and dignity of their life. Appropriate provision needed to be created which are not only culturally compatible but suitable to the needs and has potential for their earnings.Directional Move Towards Intervention

One needs to first understand the socio- cultural, personal and economic needs and requirements of the artisan along with their aspirations and then try developing clusters into professionally manage self reliant-units with a strong build up plan according to individual and collective needs of the cluster then, creating an effective member participation and mutual cooperation for the women artisan to work more cohesively within their community by encouraging each of them to work in cooperatives to facilitate the mobilization of productive resources and efficient technologies. Further to this, assessing the productive contribution of the individual woman and identifying areas where productivity can be enhanced in design, technology, and marketing, organizational skills leadership, budgeting and planning by allowing the potential in each person individually to unfold in harmonious way for their development then, moving towards identifying the current needs and future trends in craft sector and then coordinating and integrating efforts to promote skills by training them accordingly for regional, local and national markets requirements.Intervention

Artisan need a complete composite and amalgamated development plan for holistic learning and development for their empowerment. The intervention programme needs to be very broad minded approach. Training will depend on an individual’s competence level. There may be few artisans better then the others in certain skills or not good enough or are average in conceptual front or at organizational skills. All would require training of different kind and of different level according to their personal and collective needs. Structure and level plan according to the requirement of that particular cluster addressing each issue needed to be identified. The area of intervention was defined, in Design, Technology and Marketing and organizational skills.| Structure | Levels | ||

| Design | Sensitivity towards Design principals | Understanding and appreciation for local regional visual language | Synthesis of local and urban visual vocabulary |

| Technology | Understanding of hand tool equipments | Understanding of Basic machine techniques | Knowledge of application of tool for design development |

| Marketing and organizational skills | Understanding of Product development process and planning | Timely delivery and building confidence and leadership quality | Product budgeting costing, sale through effective product delivery |

Slots and Grouping

Exploring the potential further after the initial basic fundamental training, the artisans need to be offered a directional training to understand the requirements of the cluster and the skill potential that they already have and try to balance the both with the further training programme which is simplistic achievable in reality without any long durational and major training intervention since the training programme will only require the enhancement of the potential in them not a major intervention in alternative method of skill development work. This way of intervention not only will reduce the interventional time but also build confidence in the artisan because of the maturity level witch they would have already achieved in their own interested work. Catering to this structural plan then offering assistance to individuals for their development makes the intervention programme more successful. The artisan would soon learn to balance their skill potential with confidence to the demand of the markets. They will learn to balance the situation and realize, if certain skill or sensibility has not been appreciated or understood by markets in the present context, they will need to alter it or defuse it to some extend for better fit. Training needs to enhance and upgrade the available potential. It needs to begin by encouraging and pushing the cognitive skills in the artisan where knowledge, skills, and abilities of the individual artisan are brought out to the best of its potential. Knowledge referring to a body of information which they are exposed during and after the training and then applying it directly to the performance of a function without any out side helps by using their skills as an observable competence to perform a learned psychomotor act. Artisan need to apply their learnt ability as competence to perform an observable behavior or a behavior that results in an observable product. This cognitive evolution is similar to the stages of an infant development. First, the infant constructs an understanding of the world by coordinating sensory experiences (such as seeing and hearing) and then tuning this knowledge with physical actions. Infants gain knowledge of the world from these physical actions, then they perform on it. An infant progresses from reflexive, instinctual action at birth to the beginning of symbolic thought toward the end of the stage. Similarly, if the interventions are well defined in sensitive manner it will have stronger repercussions. One does not need time, improving hand skills in the embroidery patterns (which artisan already have at different level, some more or some less) which needs to be practiced by the artisan after the initial required training but what they need to be acquiring is knowledge and skills that can be directly be applied in the artisan’s own art to enable innovation appropriate to contemporary markets.In Design

The knowledge, skill and ability will make them confident in developing their own composition, colour application, line and form structures, so that they can make conscious efforts in developing their own design and try to implement their learning and knowledge by themselves into their craft practice and dovetail their new leanings of fundamentals into their interpretation of local and regional vocabulary according to their sensibilities and usage. This will encourage them to appreciate their own cultural identity without dilution of their ideas. They need to be encouraged to develop their individualistic taste in a very regionalist manner as their expression in craft vocabulary.In Technology