JOURNAL ARCHIVE

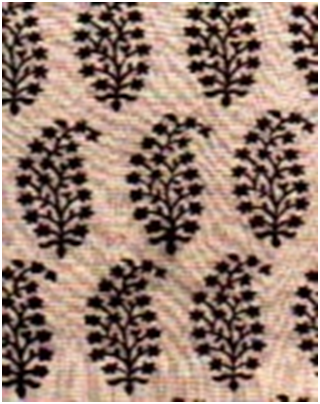

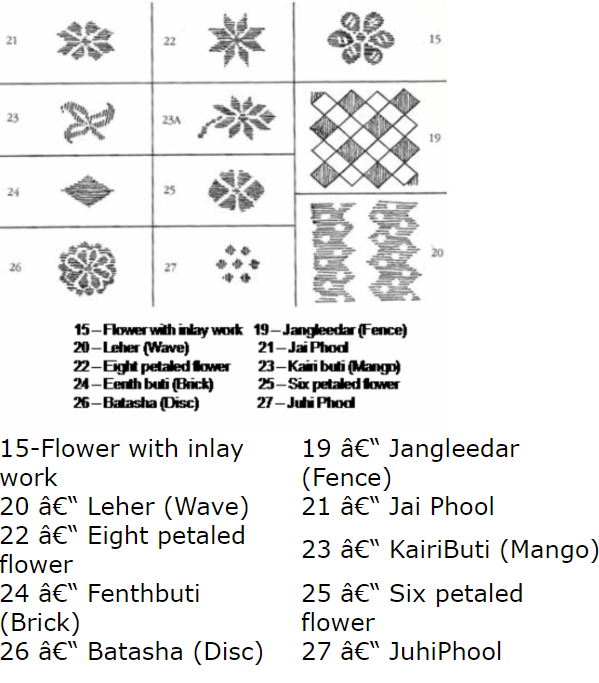

Introduction Mendh ki chapai is a resist style of printing that was practised locally in the town of Sanganer for the tribal Meena, Jat and Mali women. The wax resist enjoyed a similarity with dabu printing (Bagru village near Jaipur is famed for it), but unlike dabu which utilises mud as the resist, Mendh Ki Chappai utilised the more complex and ardous process of using beeswax as the resist material. The other special feature of the mendh was the fragrance of the fabric which was printed using beeswax/Mendh, a pleasant aroma, which was retained by the fabric for several washes. The beeswax for resist was procured from the forests, sourced from the Bhil tribal’s in exchange for money or goods, clothes or grain. In brief, the wax resisted the printed area and traditionally the colour palette was of a deep red combined with an indigo or black. With the first colour being wax resisted being the deep red colour, followed by the indigo or black colour, either in the indigo vat or mineral black colour. The origin and practise of Mendh printing is not clearly traceable, even though a very extensive library search was undertaken, but it seems to be unique to Sanganer as any information available mentions this geographic area. Sanganer is a famous printing centre and have recently acquired it geographical indication act of the small delicate floral spread that has famed the small town of printing. Sanganer is home to chippa community of printers and dyers. Chippa literally meaning the person who prints with the communities who are engaged in printing on cloth called chippas. The printing community was earlier in Amer who were brought and settled in Sanganer by Sawai Raja Jai Singh ji when his capital shifted to Jaipur. The printing settlement was near the banks of River Saraswati which is also called as Dravyavati. It is said that the waters of this river had such special qualities that it brought extra brightness in the colours, thus the colours produced in the Sanganer region had differentiable brightness. Sadly the river turned into a small canal and soon the water levels went down and the river has now completely dried up. The water supply is through motor, pumps and the water tanks. With more than 1000 families in the business of printing, the town of Sanganer is actively growing. The town contributes to the huge amounts of export of printed textiles to Asian, European and American countries. Other than the famous Sanganeri style of printing, mendh- wax resist style of printing was dominantly used for the local market. When the fine buti textile spread was used majorly for the exports and foreign markets, the bold and sharp prints were used for the local tribals. The tribal prints were resist dyed on a thick cotton cloth with floral butis on the spread of cloth namely phardas.

- The grey fabric is washed and bleached in the sun. To enhance bleaching the fabric is also bleached chemically with hydrogen peroxide. Traditionally no chemical bleaching was done and the fabric was bleached in entirety by the sun rays. The grey fabric is procured from Erode in Tamil Nadu.

- The sun bleached fabric is dried in the sun. The process is known as sukhai in the local language. The process of printing is a time-consuming process as after every step washing and drying is necessary. Process of washing is known as pachdai and drying of fabric is sukhai.

- The bleached fabric is then mordanted with harada. The process takes at least an hour. It is clearly known that natural dyes do not have affinity for the textiles. So the textile has to be made receptive to dye absorption - This process of mordanting the textiles is also known as pila karna or harada dyeing. Drying is followed.

- The fabric is printed in the usual style of Sanganer printing. In this printing two types of colours are used - red or black.The red colour printing paste is also known as begar. (Alum+ Gum+ Water+ Geru)The black colour printing paste is known as syahi. (Iron nails+ Jaggery+ Water are decomposed for 30 days, till it starts smelling foul)

- The fabric is washed and dried again.

- The fabric is now ready for the first resist printing phase. The ready mendh (Andoli ka Tel (1kg) + Cheed ka Tel ( ½kg) + Bee Wax (½ kg) + Paraffin Wax (½ kg)) in the earthen vessel or iron vessel known as mardiya is put over the heating coal. The temperature of about 65 degrees C is required for printing the wax.

- A wet cloth is put over the paatiya (Printing table). This is a very important step in the wax printing because this helps to cool off the wax on the fabric.

- The drying after wax printing is also done in shade or the wax may melt on the fabric.

- The fabric is then dyed in indigo. Two dips in indigo vat produces green colour while the 4-5 dips produce a darker indigo colour.

- The fabric is again dried in shade and then washed in hot water to remove the wax. The process of removing wax is known as ukala. Along with the hot water some soda khar is added for cleaning.

- The textile is given a final wash, rinsed and dried

Wooden or Metal hand blocks are used for the printing. One is the buti block and other is mendh block that is used to resist the printed pattern.

Brush to clean the block after printing. The wax sticks to the block which is removed by this brush.

A burner to heat the wax which is fed with coal provides the required, even heat. The earthen vessel containing wax is put over the burning coal. The wax has to be heated continuously while the resist printing is being done.

Earthen/Metal vessel (maardiya) – This is the vessel for keeping wax. It is either metal or earthen pot that can be heated while printing is carried on. There are other vessels for bleaching, washing and cleaning.

Wooden or Metal hand blocks are used for the printing. One is the buti block and other is mendh block that is used to resist the printed pattern.

Brush to clean the block after printing. The wax sticks to the block which is removed by this brush.

A burner to heat the wax which is fed with coal provides the required, even heat. The earthen vessel containing wax is put over the burning coal. The wax has to be heated continuously while the resist printing is being done.

Earthen/Metal vessel (maardiya) – This is the vessel for keeping wax. It is either metal or earthen pot that can be heated while printing is carried on. There are other vessels for bleaching, washing and cleaning.

Indigo vats, gloves and a wooden stick- Indigo vat is known as maat/math. A 9-10 feet deep pitcher in the ground whose diameter is big enough to immerse the fabric and the free movement is a vat.

Indigo vats, gloves and a wooden stick- Indigo vat is known as maat/math. A 9-10 feet deep pitcher in the ground whose diameter is big enough to immerse the fabric and the free movement is a vat.

Uniqueness Or The Reason For Decline

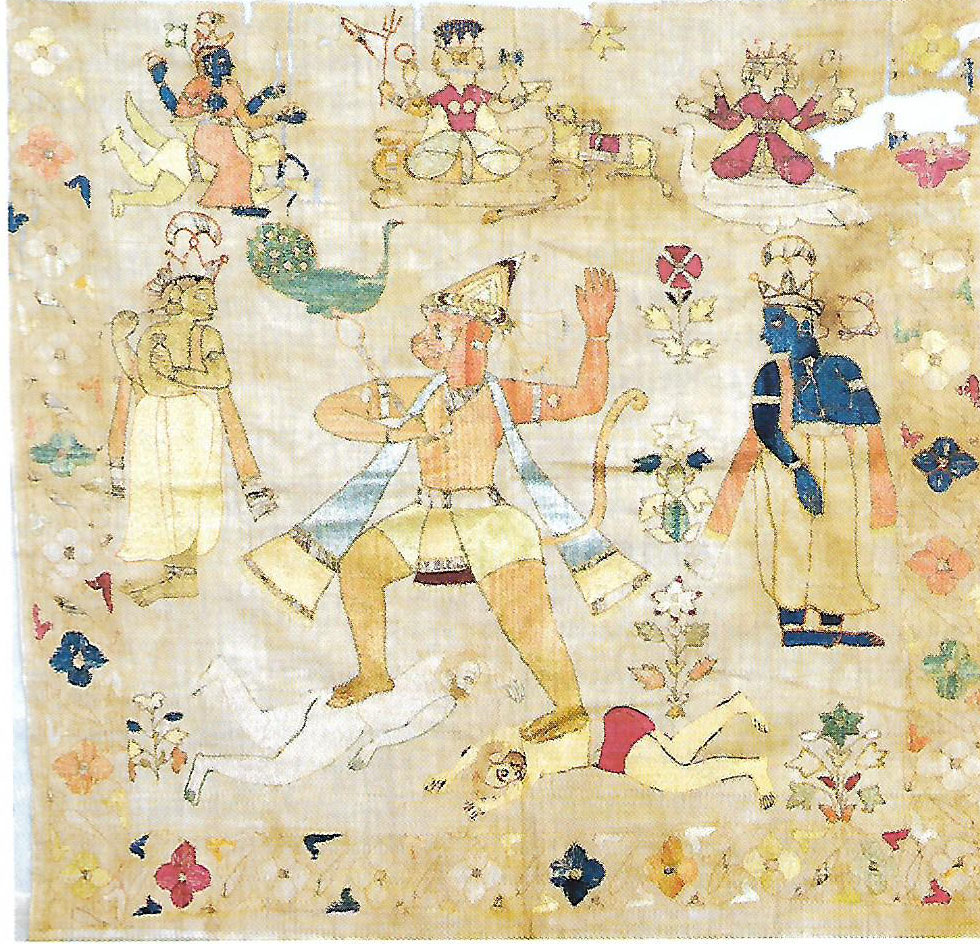

Cloth Hand woven fabric with a relatively low cotton count with substance and thickness enough to keep cool in summer and warmth in the cold. This special fabric was known as reja, thick coarse cotton cloth with the toughness to bear the daily rough wear. This tough fabric required special processing for it to be able to accept and retain colour, to a brightness and depth that was acceptable to the client. The processes of printing as followed for finer textiles was not sufficient for the reja, as the coarse thick fabric did not readily accept or retain the colours from this process. The beeswax in mendh ki chappai sank into the thick fabric, allowing it to retain the original richness of the colour resisted, while simultaneously allowing for repeated dips in the indigo or/and black dyes. The whole 5 square feet textile was used to make ghaaghras/lehengas. The phardas were yellow or jummerdi in colour. The Mali women wore lehenga of blue and red fabric, on which butas of coriander leaves, betel leaves, chaubundi etc were printed. They wore green dupattas with the motifs of dhaniya and chaubundi. While the Meena and other peasant classes wore yellow pharda. Jat women only wore red and black coloured chundaris.Replaced now by machine made textiles that now provide the main base for printing, the printer no longer needs to follow the demanding process of printing with mendh. The machine made reja cloth has become much more popular among the peasant communities of Jat, Mali and Meena women. The traditional consumers are no more wearing the mendh printed phardas. The reason perhaps is the availability of cheaper fabrics and the less demand for traditionally printed textiles. Presently there is no knowledge about the use of these products by these communities.

This change in base textiles usage has removed the necessity of using a wax resist process for printing. Removing distinctions in the type of blocks used, bringing uniformity to the processes that were earlier clearly defined, with printers specialising in techniques required for different clients, their individual pockets and base textile requirements. Blocks The mendh printing requires very fine blocks for printing in order that the resisted prints appear defined with greater clarity. Wooden or metal blocks have both been used in printing mendh. The blocks for mendh/beeswax printing are preferably made of metal, as the wax can be easily removed from the metal block. Though wooden blocks can also be used but they require extensive cleaning every time. The blocks are of three types – gad/background, rekh/outline and data/filler. These are the main buti blocks. The blocks for resist mendh are separate and need to have the same fineness and quality as for the buti block.The metal blocks being expensive compared to the wooden blocks and the preparation time lengthier is not used by the printing industry any more for any type of printing.

There has been a ban on the forest products due to black marketing and unnecessary deforestation and resource exploitation. Such bans have caused the crunch in raw material available and shooting up the price twice as much it was earlier.

Conclusion Of all the possible situations of prise rise of raw material, changing consumer buying behaviour, ardous printing procedure, and ban on some raw materials there is one problem that ties them all and that is the ignorance of people. This particular craft had been ignored in every aspect of its existence. Without proper intervention from either the craftsmen or the government the survival of the craft could not have been possible. The myriad possibilities of revenue that the direct style of printing was fetching the craftsmen they couls easily completely neglected the craft of local importance. The government negligence on providing no provisions for raw materials that have been otherwise banned aggravated the problems. And with the wide possible choices of fabric at much cheaper rates gave more buying power to the consumers in every promising way. Mass produced fabric have removed the differentiable community characteristics that were prominent through their clothing. Uniformity in the mass produced fabric has washed out the distinctness of individual fabric requirements across castes and communities. The rapidly changing patterns of the industry have caused the craftsmen to lose their ingenuity to the traditional styles.Hand screen printing is a common technique that has been carried out for years in the textile pockets of the country. It is essentially a stencil process. An open mesh fabric is used to hold in place the 'islands' of the stencil design through which inks are forced using a flexible blade of rubber or polyurethane called a squeegee.

History of Hand Screen Printing Screen printing is not a very old process. Some of the earliest applications can be found in medieval Japan. It appeared in Europe in the 18th century, particularly in France for stenciling patterns on to fabric In the 19th century it remained a simple process using fabrics like organdy stretched over wooden frames. Only in the twentieth century did the process become mechanized, usually for printing flat posters, packaging and fabrics. It became widely used to print colored wallpaper as a cheaper alternative to printing with wooden blocks.

Regions Known For Hand Screen Printing in India- Gujarat : Ahmedabad , Surat, Deesa, Kutch , Mandvi, Dhamadka, Mundra, Anjar, Jamnagar,Surendernagar, Jetpur, Vadodara

- Maharashtra : Bombay

- Delhi

- Haryana : Faridabad

- Rajasthan : Jaisalmer and Barmer, Jaipur, Sanganer, Bagroo, Pali

The first stage in the process of screen printing is the procurement of the fabric straight from the mills. Screen printing can be done on a whole range of fabrics. It can be done on cotton, jute, silk, polyester and any many more. The below mentioned fabrics are the most common used for screen printing -

- Sheeting (Markeen) 20/20 is the most commonly used fabric for printing. 20/20 is the yarncount by which the fabric is recognized, locally called the ‘taana-baana’ or warp-weft count. Thefabric construction of this sheeting is 60/60.

- Canvas is also used in large quantities mainly for home furnishings. The yarn count is again20/20 and fabric construction is 100/120.

- Voile is available in various thicknesses. The thinnest voile of 70/90 count is used aslining. The 80/80 voile and 100/100 voile are the good quality fabric for garments.

There are two main type of dyes used for printing:

There are two main type of dyes used for printing:

- Vat dyes

- Pigment dyes

- ink modifiers/ reducer - to adjust the viscosity of the ink

- extender - to retard drying speed if printing a big run

- solvent - to clean up with after the printing is over

- Transparent: These are "low solids" pigments: when the fabric is dry there is very littleresidue left on the fabric. They most closely simulate the look and feel of dye prints. They arevery transparent, which means that a color printed on top of a colored ground will be affected bythe color of the ground fabric. The transparent pigments have very limited use on darkgrounds.

- Opaque: These are "high solids" pigments: when the fabric is dry there is lots of residueleft on the fabric. They cause the fabric to be stiffer than the transparent pigments. However,they can be used to print light colors on dark grounds. Opaque pigments will soften when washed,and are not as harsh on the hand as a plastisol ink.

- Metallic: These are “high solids” and relatively opaque. To achieve a metallic look, it isnecessary that the metallic pigment remain on the fabric after printing. They are often made upof plastics, mica, and natural oxides.

The raw fabrics are mainly procured from large textile mills in Ahmedabad; Century Mills and Anglo French Mills in Pondicherry; Tirupati Mills and others from Bombay and Rajasthan. All the three main fabrics procured: sheeting, canvas and voile are 100% cotton. They are called as ‘Gray’ fabrics before the pre-dyeing stage. They are stored in the ‘Gray room’ where the fabric is first checked on lighted glass tables for any kind of defect before it is sent for dyeing.

Tools Used Wooden table:

A screen printing wooden table 18 m long (the longer the better) consists of a printing surface:a smooth table top or sheet of plywood with hinge clamps (gittis) attached. The ply surface iscovered with a jute fabric cover and a thick cloth to make the surface smooth. Below the ply is alayer of asbestos.

Wooden table:

A screen printing wooden table 18 m long (the longer the better) consists of a printing surface:a smooth table top or sheet of plywood with hinge clamps (gittis) attached. The ply surface iscovered with a jute fabric cover and a thick cloth to make the surface smooth. Below the ply is alayer of asbestos.

Steam boiler:

The boiler is connected through pipes, which run below the wooden tablebetween the asbestos sheet layer, and the printing surface. The heat produced by the boiler andtransferred through the pipes keeps the table warm, hence speeding up the drying process and alsoenhancing the color tones. Usually the heat provided is between 30-40 degrees C. It depends onthe kind of design: a dense design needs a higher temperature.

Steam boiler:

The boiler is connected through pipes, which run below the wooden tablebetween the asbestos sheet layer, and the printing surface. The heat produced by the boiler andtransferred through the pipes keeps the table warm, hence speeding up the drying process and alsoenhancing the color tones. Usually the heat provided is between 30-40 degrees C. It depends onthe kind of design: a dense design needs a higher temperature.

Screens:

The screen consists of a frame of wood or metal, stretched with mesh (jaali)made of monofilament polyester nylon fibers. The mesh count is simply the number of threads perlinear inch that are woven into the mesh, and is usually determined by the type of ink to be usedfor printing. Generally a mesh count of 16/64 is used. Finer mesh will allow a thinner inkdeposit. This is a desirable effect when printing very fine detail and halftones. Typically afine mesh should be 200-260 threads per inch. Water based inks work best on finer mesh. These aregenerally used in graphic and industrial printing. Course mesh will give a heavier ink deposit.This type of screen is used for flatter, open shapes. Typically a course screen mesh will be160-180 threads per inch. These are generally used in textile printing.Wood frames have been replaced by metal because they do not warp with water. The most commonly used types of wood are cedar and pine. Pine is preferred because it is more water resistant while it is light-weight. Metal frames are made out of aluminum or steel. Aluminum is generally preferred because it is light-weight yet sturdy. There are some applications where steel is preferred such as in very large printing frames used for long printing runs.

Screens should be as big as possible. Smaller screens are less expensive, but they are very hard to use. The margin between each side of the design and the inside of the frame should be at least 1/3 of the image size. So for e.g. for a design of size 18 x 24-in., the inside dimension of the screen should be 30 x 40-in. 1/3 of 18 = 6, so the top and bottom margins must be 6 in. each; 1/3 of 24 = 8, so the left and right margins must be 8 in. each; 18 + 6 + 6 = 30; and 24 + 8 + 8 = 40. This is the minimum size.

Screens:

The screen consists of a frame of wood or metal, stretched with mesh (jaali)made of monofilament polyester nylon fibers. The mesh count is simply the number of threads perlinear inch that are woven into the mesh, and is usually determined by the type of ink to be usedfor printing. Generally a mesh count of 16/64 is used. Finer mesh will allow a thinner inkdeposit. This is a desirable effect when printing very fine detail and halftones. Typically afine mesh should be 200-260 threads per inch. Water based inks work best on finer mesh. These aregenerally used in graphic and industrial printing. Course mesh will give a heavier ink deposit.This type of screen is used for flatter, open shapes. Typically a course screen mesh will be160-180 threads per inch. These are generally used in textile printing.Wood frames have been replaced by metal because they do not warp with water. The most commonly used types of wood are cedar and pine. Pine is preferred because it is more water resistant while it is light-weight. Metal frames are made out of aluminum or steel. Aluminum is generally preferred because it is light-weight yet sturdy. There are some applications where steel is preferred such as in very large printing frames used for long printing runs.

Screens should be as big as possible. Smaller screens are less expensive, but they are very hard to use. The margin between each side of the design and the inside of the frame should be at least 1/3 of the image size. So for e.g. for a design of size 18 x 24-in., the inside dimension of the screen should be 30 x 40-in. 1/3 of 18 = 6, so the top and bottom margins must be 6 in. each; 1/3 of 24 = 8, so the left and right margins must be 8 in. each; 18 + 6 + 6 = 30; and 24 + 8 + 8 = 40. This is the minimum size.

Squeegees:

A squeegee is a rubber blade gripped in a wooden or metal handle, which ispulled across the top of the screen. It pushes the ink through the mesh onto the surface of thecloth to be printed. Good squeegee blades print better and last longer. They come in variousdegrees of hardness. Medium hardness is the best. The longer the squeegee, the more difficult itis to print with, so it is always better to print with the squeegee running parallel to theshorter dimension of the screen. However, the squeegee should be at least 2 inches longer thanthe widest design to be printed.

Squeegees:

A squeegee is a rubber blade gripped in a wooden or metal handle, which ispulled across the top of the screen. It pushes the ink through the mesh onto the surface of thecloth to be printed. Good squeegee blades print better and last longer. They come in variousdegrees of hardness. Medium hardness is the best. The longer the squeegee, the more difficult itis to print with, so it is always better to print with the squeegee running parallel to theshorter dimension of the screen. However, the squeegee should be at least 2 inches longer thanthe widest design to be printed.

The Process of Hand Screen Printing The process of screen printing is of two main types:

Technique Based:- Table printing: Table printing method is none other than hand screen printing where woodenor metal screens are used and printing is done manually.

- Flat-belt printing: Flat belt printing is when the table is moving and the screen is set in a position.

- Rotary printing: An automated form of hand screen printing, Rotary screen printing works onthe same principle, but the screen is wrapped onto a cylinder that can be rotated, and the inksare applied from inside the cylinder with a squeegee.

- Pigment printing: It is like a coating of color on the fabric surface. The color does notseep into the cloth, hence its best done on a light colored base. The color fastness is very lowbut it is a much easier and faster process of printing. Pigment printing is used most for homefurnishings where the cloth does not have to be washed too often.

- Discharge printing: This process "extracts" the dye present in the fabric and replaces itwith the dye in the ink. The value of this process is that it gives the softest hand possible tothe fabric after printing and the color fastness is very good. Printers use it on dark fabrics togive them a hand similar to that possible on light fabrics with regular inks. After printing, thefabric is placed into or runs through a drying chamber where the old dye "steams" out and isreplaced.

The artwork or designs to be printed are either provided by the agencies placing the order with the textile unit or are supplied by the printers themselves based on traditional designs found in the region. They may also be inspired by designs published in various books or magazines, the latest forecasts predicting the color stories and print /graphic directions or from an existing line. Once the artwork is ready, one needs to color-separate the design so that different screens can be made for each color.

The artwork or designs to be printed are either provided by the agencies placing the order with the textile unit or are supplied by the printers themselves based on traditional designs found in the region. They may also be inspired by designs published in various books or magazines, the latest forecasts predicting the color stories and print /graphic directions or from an existing line. Once the artwork is ready, one needs to color-separate the design so that different screens can be made for each color.

Color separating a design from the original artwork means breaking down the design by color into a number of separate designs, from which screens/masters are made. The separations are printed over each other in layers, to create the original design. There are a number of ways to achieve color separations:

Color separating a design from the original artwork means breaking down the design by color into a number of separate designs, from which screens/masters are made. The separations are printed over each other in layers, to create the original design. There are a number of ways to achieve color separations:

- Using artwork pens to trace the design and draw on an overlay sheet

- Taking a number of photocopies and blocking the unwanted portions

- Computer scanned imaging & graphic color separation

This process is best performed using a lighted glass table, where light shines through the design, highlighting the areas to be copied. A separate tracing paper is used for each new layer/color separation such that each color is on its own piece of tracing sheet. When the sheets are superimposed on each other the original design is created. The ink used is opaque and completely black. The black areas of the tracing sheet are where the ink, of any color, will pass through the screen.Gray areas will give unpredictable results. Line thickness and fineness of detail are limited by the fabric to be printed on, screen mesh used, inks used, and other minor factors.

This process is best performed using a lighted glass table, where light shines through the design, highlighting the areas to be copied. A separate tracing paper is used for each new layer/color separation such that each color is on its own piece of tracing sheet. When the sheets are superimposed on each other the original design is created. The ink used is opaque and completely black. The black areas of the tracing sheet are where the ink, of any color, will pass through the screen.Gray areas will give unpredictable results. Line thickness and fineness of detail are limited by the fabric to be printed on, screen mesh used, inks used, and other minor factors.

By Hand: Blocking the Design By taking multiple copies of the original design, each separation is created by blocking out parts on each layer. This process is more accurate than tracing the design as each design is identical. However, blocking requires more thought and delicate separation, as complex designs (5 colours or more) can get confusing.

Transferring the Design Onto Screens Step 1 Preparation A metal frame of the size of the artwork is pulled out. Red lacquer is applied over the frame to prevent it from rusting over time. Then the mesh is stretched over the frame and nailed to hold it in position and red lacquer is applied again

Step 2 Cleaning the mesh

After the screen is stretched on the frame, there are still many dust particles adhered on the screen even though they are not visible to the naked eye. Hence the screen is washed with soap and left to dry.

Step 3 Mixing the screen emulsion

Photo screen emulsion is mixed with sensitizer (ammonium dichromate) before using. This is because they have a longer shelf life before they are combined. The ratio is 10:1 (e.g. in 1 kg emulsion put 10 g sensitizer). This is done in a dark environment. A thick coating of the emulsion is then applied on the screen and left to dry under the fan for almost an hour till it completely dries.

Step 4 Photo Stencil Exposure

Step 2 Cleaning the mesh

After the screen is stretched on the frame, there are still many dust particles adhered on the screen even though they are not visible to the naked eye. Hence the screen is washed with soap and left to dry.

Step 3 Mixing the screen emulsion

Photo screen emulsion is mixed with sensitizer (ammonium dichromate) before using. This is because they have a longer shelf life before they are combined. The ratio is 10:1 (e.g. in 1 kg emulsion put 10 g sensitizer). This is done in a dark environment. A thick coating of the emulsion is then applied on the screen and left to dry under the fan for almost an hour till it completely dries.

Step 4 Photo Stencil Exposure

A separate screen is made for each color in the artwork such that when all of them placed over each other would create the original design. Once the coating has dried, the positive film is placed on the camera table. Then the screen is placed in the exact position for a mirror image to be taken. The camera (lighted table) is switched on and the screen is exposed to the light for 1.25 minutes. The exposure time could vary depending on the design. The light does not pass through the black/opaque areas and the rest of the screen gets exposed. The exact design may not be visible completely till the emulsion is washed off.

Step 5 Screen Washout

The screen is taken to the washout stand and a jet of water is used to wash off the emulsion till the screen mesh is visible.

A separate screen is made for each color in the artwork such that when all of them placed over each other would create the original design. Once the coating has dried, the positive film is placed on the camera table. Then the screen is placed in the exact position for a mirror image to be taken. The camera (lighted table) is switched on and the screen is exposed to the light for 1.25 minutes. The exposure time could vary depending on the design. The light does not pass through the black/opaque areas and the rest of the screen gets exposed. The exact design may not be visible completely till the emulsion is washed off.

Step 5 Screen Washout

The screen is taken to the washout stand and a jet of water is used to wash off the emulsion till the screen mesh is visible.

- Direct dyes

- Procion dyes

- Ramazol dyes

Once all the supplies are assembled: the screens, the colors and the dyed fabric, the next step is to set the table for printing. The dyed fabric is laid on the table and stretched firmly using soft pins at close intervals. Then the hinge clamps or stoppers (‘gittis’ as they are called locally) are set.

Once all the supplies are assembled: the screens, the colors and the dyed fabric, the next step is to set the table for printing. The dyed fabric is laid on the table and stretched firmly using soft pins at close intervals. Then the hinge clamps or stoppers (‘gittis’ as they are called locally) are set. The setting of the gittis requires skill. The screen for the first color to be printed is kept on the printing table. Three registration stops are marked on the surface of the printing table. These are such that there is one stop at each of the lower ends of the design to be printed, and one right in the center. The registration stops ensure that the placement of the screen is in exactly the same place each time relative to the image printed.

The setting of the gittis requires skill. The screen for the first color to be printed is kept on the printing table. Three registration stops are marked on the surface of the printing table. These are such that there is one stop at each of the lower ends of the design to be printed, and one right in the center. The registration stops ensure that the placement of the screen is in exactly the same place each time relative to the image printed.

- Testing the screen to see if the image has been burned in properly, identifying forpinholes, blockages, and any other areas of deficiency.

- Checking the repeat to find the most accurate measurement.

- Testing the colors to see if there is any color shift between color dabs and productionconditions.

- Testing the ground under production conditions.

-

- Firstly, in production alternate frames are printed. Errors in the repeat do not show upuntil all the fabric has been committed and the alternate frames are filled in. Also, if thefabric shrinks too much it may ruin the repeat. Shrinkage sometimes does not show up until 30minutes after the fabric is printed. It is then too late to fix the problem. There may be largelosses of fabric, at the customer's expense.

- Secondly, prices are based partially on the maximum use of the print tables. To hold up theuse of a 30 m table to test 5 m is not efficient, and would result in higher prices all around.Unfortunately, it takes almost as much energy and labor to print 5 m as it does 30 m. Screenshave to be pulled, fabric set, gittis set, colors mixed, fabric has to dry, screens to be cleanedand put away. Many of these tasks take the same time whether 1 m is printed or 60 m. Theefficiencies of scale play an important role in hand printing small runs.

‘Screen printing is like ski jumping. Once you start, there's no convenient stopping place until the end.’

The process of hand screen printing involves two people at a time. The screen for the color that prints first is pulled out and positioned on the printing table, position set according to the gittis (stoppers). The first color is poured on to the screen and two people walk up and down the tables printing each color frame by frame, with the large squeegee pushing the desired color through the screen onto the fabric. Every alternate frame is printed. By the time the first round is over, the colours would have dried and the fabric would be ready for the second round of printing. This way, the process is repeated as many times as the number of colors to be printed.

Color Check After the cloth is printed and completely dried, it is put into the boiler and steamed so that the colors come out intense and dark. This process also makes the colors seep into the cloth ensuring a fine hand.

After the cloth is printed and completely dried, it is put into the boiler and steamed so that the colors come out intense and dark. This process also makes the colors seep into the cloth ensuring a fine hand.

After the desired color has been achieved, the fabric is washed. It is uring this time that the fabric might shrink by 8-10%. After it dries, it goes for quality check. The quality check is done for misprint or overlapping of design, bleeding of colours, large intervals between the screen shifts and color fastness.

After the desired color has been achieved, the fabric is washed. It is uring this time that the fabric might shrink by 8-10%. After it dries, it goes for quality check. The quality check is done for misprint or overlapping of design, bleeding of colours, large intervals between the screen shifts and color fastness.

The hand screen printed fabric is used in a variety of purposes mainly for home furnishings and garments. Home furnishings include quilted products like quilts, pillow covers and cushion covers and non-quilted items like table covers, bed covers, bed skirts, runners, mats, napkins, cushion covers, pillow covers and curtain panels. Garment accessories like scarves, bandanas and sarongs are also quite in demand for the export markets.

Marketing

Screen printed fabrics have good markets both in India and abroad. The main markets for this fabric are in the US, Germany and Hungary. Recently Japan has also shown interest in screen prints coming from India. There is a huge demand for screen printed fabric in the domestic market also.

Changes in Recent Years

By definition, a print is an image that has been produced by technical means, which enables it to be multiplied. The art of hand block printing and screen printing to produce attractive fabrics of rich colors and patterns is age old. With an ever increasing market for these printed textiles in oversees markets, newer designs and color combinations are being constantly experimented with. With new market directions, new technologies like rotary printing and ink-jet printing are emerging with fast growth and strong market penetration.

The hand screen printed fabric is used in a variety of purposes mainly for home furnishings and garments. Home furnishings include quilted products like quilts, pillow covers and cushion covers and non-quilted items like table covers, bed covers, bed skirts, runners, mats, napkins, cushion covers, pillow covers and curtain panels. Garment accessories like scarves, bandanas and sarongs are also quite in demand for the export markets.

Marketing

Screen printed fabrics have good markets both in India and abroad. The main markets for this fabric are in the US, Germany and Hungary. Recently Japan has also shown interest in screen prints coming from India. There is a huge demand for screen printed fabric in the domestic market also.

Changes in Recent Years

By definition, a print is an image that has been produced by technical means, which enables it to be multiplied. The art of hand block printing and screen printing to produce attractive fabrics of rich colors and patterns is age old. With an ever increasing market for these printed textiles in oversees markets, newer designs and color combinations are being constantly experimented with. With new market directions, new technologies like rotary printing and ink-jet printing are emerging with fast growth and strong market penetration.

Issue #10, 2023 ISSN: 2581- 9410

Hand spinning is an ancient technique and it is considered that it started in India. The craft form initially used the hand spindle or drop spindle technique to spin the natural fibres. The equipment like Doshi Charkha (traditional big wheel charkha) or other Kisan Charkha or Peti Charkha (Box Charkha) came into existence later. It was a wide spread practice in Indian villages to hand spin the local fibres like wool and cotton using Charkhas. Each region of state of India has their unique Charkhas.

Khamir’s tryst with hand spinning started with Kala cotton initiative. In 2007, after completing weaver solo exhibitions at New Delhi, we conceived the entire concept and started organising it, the hand spinning on Ambar Chakha was inherent part of the concept. As there were no Ambar spinners available in Kutch, we approached Udyog Bharti, a Khadi organisation based in Gondal city of Saurashtra to help us. They dedicated one of their group of spinners for the process. As payment of Khadi was decided on counts and Kala cotton was a coarse fibre with possibility of thicker count of 20s or less than it, the payment was lower than other Khadi counts of 30s and 40s. Also, there was a lot of struggle on the part of weavers to organise the weaving. We also provided continuous feedback to the hand spinners, which we receive from the weavers. The team members of Udhyog Bharti were kind enough to hold the spinning for almost two years, after that they told us to organise it elsewhere. We started looking back in Kutch and approached the Khadi organisations here. As it didn’t work out through Khadi organisations, we took the work in our hands to organise Ambar spinning on our own. We identified hand spinners in Tara Majal village, who own Ambar Charkhas and were not associated with any Khadi organisation. We started working with a group of 7 women there. The first task was to upgrade the Ambar Charkhas as many were not in working condition.

A hand spinner from Arikhana village, one of the hand spinners joined hand spinning recently (Photo courtesy: Fumie) (24th January, 2023)

We were in search of a technical person and the spinning women gave us a name of Mansangbhai, who was working with a Khadi organisation at that time. We searched for Mansangbhai and located him in Bhuj where he was working as a gate keeper of an ATM. We requested him to allocate some of his time for the hand spinning initiative. Mansangbhai helped us to improve the conditions of Ambar charkha and also organised the registration of the hand spinners in 2015-16. His continuous engagement helped to increase output and earnings of Ambar spinners. We expanded the hand spinning with Mr. Bimal Bhati joining the team in July, 2017. Bimal having a degree in textile technology, was working with production department at Welspun industries in Anjar before shifting to Khamir. He worked with wool spinners in Khamir. His technical understanding helped to organise wool spinning. He joined cotton spinning work as a coordinator. His sustained interest and inputs helped us to spread our work to nearby villages. The request mostly came from the existing spinners of Manjal, who wanted us to give hand spinning work to their relatives living in nearby villages. We spread to Sanosara and Nana Nandra villages. In parallel, the processing of Kala cotton was organised in form of a cotton mill located in Paddhar village. That helped us to organise the supply of rovings and carded cotton locally.

A hand spinner from Arikhana village, one of the hand spinners joined hand spinning recently (Photo courtesy: Fumie) (24th January, 2023)

In an internal review of Kala cotton initiative in 2018-2019, Archana Shah, founder of Bandhej, suggested to Khamir to promote pure hand spinning. We didn’t put conscious efforts in that direction, but when we tried, the journey of hand spinning took an easy turn from Ambar charkha to single needle Peti charkha (Box Charkha). Bimal met few women who were familiar with the Box Charkha spinning and having small instrument with them too. He gave them raw cotton and asked them to prepare the yarn. Thus, the first samples were prepared. The hand spinning on Box charkha was a slow production process, but it helped to revive the hand spinning skills and generates a lot of livelihoods by giving work to more women.

A hand spinner from Arikhana village, one of the hand spinners joined hand spinning recently (Photo courtesy: Fumie) (24th January, 2023)

The journey with hand spinning started towards beginning of 2019 on Peti charkha with three spinners in Nandra village, Abdasa block of west Kachchh. This revival of hand spinning technique which was lost or stopped before the earthquake has come alive after almost 3 decades. We needed to organise the carded cotton from the mill in form of Puni. This was procured easily from the Paddhar spinning mill which was set-up by two local entrepreneurs after they noticed the potential of kala cotton for the region.

Hand Spinners from Mota Nandra village, one of the first hand spinners of Kala cotton with Peti charkha

The number of hand spinners slowly and steadily increased. We did a training with Nagendra Poludas Satish of Kora design. The training helped us to understand the count based hand spinning system. We introduced the same on the ground and transferred the current weight based payment system to count based payment system. This new system helped us to rationalise wages as well as organise the yarn properly for weavers. The spinners were introduced to the entire weaving system so that they could understood the importance of counting system.

Lady Bamford Foundation, Jaipur sanctioned a training support grant to hand spinners. We enrolled 30 new spinners under the support and expanded our work to Moti Vamoti village and organised a training of spinners from the village. The Covid pandemic started in the middle of the training and soon we understood that it is very important to provide continuous work to hand spinners at their homes during the pandemic like situation.

We organised an online fund raising campaign called “Kantai Se Kamai” to include more hand spinners during Covid. The campaign received tremendous support. One of our well-wisher put us in touch with Mr. Vikram Lal of Lal family foundation. He liked the idea and immediately sanctioned the support. This gave a new boost to our ground efforts and number of women doing hand spinning doubled to 80 in a short period of time. We increased the work intake during the peak of Covid waves to ease the income, livelihoods related issues. We also introduced a yearly bonus system. This system was introduced to increase the income of spinners and recognise and encourage those who are doing good work.

A grand mother and grand dauther with the book “Craft future”, which has their combine photo on the cover. At the event in Bhuj haat (8th October, 2021)

We continued our efforts after Covid pandemic. We started celebrations and encouraged coming together of hand spinners. Post Covid pandemic, one such program was organised at Bhuj Haat, where large number of hand spinners joined together for the first time. Archana ben Shah wrote a book titled “Crafting future” and a hand spinner grandmother and daughter received a space on the cover page of that book. We celebrated that achievement in presence of same grandmother and daughter at the event. It was one of the rare recognitions received.

Hand spinners spinning together during Ratia Baras celebrations on 21st September, 2022 at Khamir

We initiated the celebration of Retia Baras, a birthday of Gandhi ji according to Indian calendar with spinners on 22nd September, 2022. We invite spinners across all the villages to Khamir campus and they spin together. In last such celebration, we invited hand spinners of Rajasthan associated with Nila House. It was a unique get together and celebrations of hand spinners working and living in distinct regions.

The number of hand spinners actively working with us are 125 and Ambar spinners are 15. We wish to create a unique model to demonstrate that hand spinning is a relevant idea in present times.

Hansaba, A Kala cotton spinner speaking at the event in Bhuj haat (8th October, 2021)

Khamir’s main objective to encourage the hand spinning as part of Kala cotton is to revive hand spinning skill and provide sustainable income to women based in villages. The women living in villages has limited work options. Moreover, we work with the women of Darbar communities who do not venture out of their home to earn livelihoods. The hand spinning is not a full time livelihood and women can do it at their own pace and free time once they complete their house hold work. The average income is somewhere between 1500 to 3000 based on amount of work done and yarn count. We also provide them yearly bonus of 10 to 15 % according to the scale of work done by them.

The initiative has opened up many possibilities of connecting hand spinning with handloom weaving. The initiative is generating interest among young spinners and weavers. Many young girls are spinning at home in their free time. The hand spinning is also part of Khamir’s craft curriculum initiative.

Abstract

Our understanding of design has been evolving steadily over the past 100 years and in recent years there has been a rush of new research into a variety of dimensions and Ethics is one the many dimensions that have received research attention. In this paper we look at the various dimensions of design and at current and past definitions to see the contemporary understanding of the subject as we see it today with the aid of models that the author has evolved over several years of reflection and research.

We then trace the evolution of design as a natural human activity and restate this history in terms of the major stages of evolution from its origins in the use of fire and tools through the development of mobility, agriculture, symbolic expression, crafts production and on to industrial production and beyond to the information and knowledge products of the day. This sets the stage to ponder about the future of the activity and of the discipline as we see it today.With the use of a model the expanding vortex of design value and action is discussed with reference to the role of ethics and value orientation at each of the unfolding stages through which we have come to understand and use design over the years. Beginning with the material values of quality and appropriateness we explore the unfolding dimensions of craftsmanship, function, technique, science, economy and aesthetics that has held the attention of design philosophers and artists over the post renaissance period.

In the last fifty years our attention has shifted through the work of several design thought leaders to aspects of impact of design on society, communication and semiotics, environment and even on politics and culture with some discussion on each of the major contributors in this ongoing discourse. The further developments that lead to systems thinking and on to the spiritual levels are introduced to place the ethical debate at the centre of the design discourse at each of these levels of engagement.Some critical case examples are introduced to exemplify the arguments that have been made to establish the various levels of ethical actions that design has discovered and with these the author will argue that design is evolving to a more complex form that will require new kind of integrated design education that is already being experimented with across the world in the face of a series of crisis that we have been facing in industrial, economical, social, and most visibly at the political and ecological levels. These ethical lessons are still diffuse and disconnected in the fabric of design action across the world and we will need to find ways of bringing these to the hand, head and heart of design education if we are to find a new value for design that will help us address the deep crisis that we are facing today.

The full paper addresses the following six questions by expanding on each as we go forward with the discussions that each question entails.

|

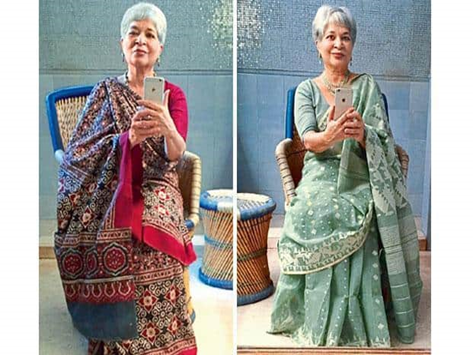

In the late 1990’s when Craft Revival Trust started its explorations of the bylanes and corners of craft practice amongst the first traditions tracked were those of handblock printing and dying. The unearthing of the carved bust of the priest-king at Mohenjodaro draped in a shoulder cloth with trefoil motifs, references in ancient texts, visual and archaeological evidence all date the dyeing and patterning of textiles on the sub-continent back several millennia. Of the many traditions of handblock printing that continue to be practiced in India from the celebrated to the relatively unknown, the tradition of Bagh in Madhya Pradesh holds its own. This bustling small township known for its ancient Buddhist mural painted rock cut caves is home to the Khatri chippas the hereditary printing and dyeing community. The Khatris trace their ancestry to Larkana in Sind from where their long march eastwards began over 400 years ago. Their wanderings led them to several places including Bagh where they settled near the mineral rich waters of the Baghini River, its flowing waters vital to the printing process. Catering to the textile needs of the regions tribal populace of Bhil and Bhilals the Khatris printed and dyed the lugada saris, ghagra full length gathered skirts, angocha shoulder cloth and odhni head mantles. This customary wear was worn for occasions like weddings and celebrations and ppurchased by tribal communities either with cash or bartered with forest produce during the lunar month of Kartik, around Diwali and at Phagun, the harvest period around the festival of Holi With changing times and the availability of cheap mill made textiles the ties between the block-printer and their traditional tribal patrons diminished and the Khatris of Bagh began to explore new avenues to stay relevant. The patriarch of Bagh printers the late Hajji Ishmael Khatri, awarded by the President of India with the honorific of Shilpguru, was instrumental in placing Bagh on the handblock print map. In the late 1980’s he collected disused blocks from other printers, made new blocks from old and damaged ones, researched and single handedly collated and built up the Bagh motif directory. This design repertoire rooted in tribal culture extended from floral butis and vines to a vast range of jaal trelliswork and geometric patterns, all startlingly contemporary in look. Ishmael experimented with layouts and colors, created variations in shades and established Bagh as a block printing center to be reckoned with. The printers in Bagh follow the mordant dye printing technique to create their striking deep red and iron black handblock printed textiles. This complex manual process requires patience, skill and dexterity with the printing of a sari, for instance, taking a minimum of three weeks to complete. At the very core of the process is the block itself, with the quality of the print dependant on the skill of the block-maker. Intricately carved by specialist block-makers in Pethapur, Gujarat in long lasting teak wood, the block-makers follow the exact specification of the printers. Even before the printer starts the process of stamping the first block several steps have to be completed to ready the fabric to accept the print and the color. The cloth either cotton or silk is first washed to remove all impurities and then soaked overnight in a mixture of arandi-ka-tel/unrefined castor oil, alkaline mineral salts and goat dung. When this mixture is completely fused into the fabric it is then treated with harda/myrobalam nut powder. These processes soften the fabric making it receptive to the dye and ready for printing. The printer lays the cloth onto a low table, dips the block, usually 6x6 inches in size, into the color tray ensuring that no extra color adheres to the block. He then carefully places the corner of the block on to the fabric setting its position before lowering the whole block down. With a firm, sure hand he thumps the block with his fist thus ensuring an even print. This process is then repeated again and again till the whole fabric is printed. Each print aligned and flush with the next. With experience a block printer can average about ten meters in a day. The deep black color is extracted from rusted iron fermented with molasses or as is more common now from iron ferrous sulphate/ hara kasish. The shades of red emerge when the patterns printed with the mordant alum are dyed in the synthesized alizarin red dye bath. Boiled in huge copper vats set on wood fired furnaces, the yellow Dhavda/Axle wood tree flowers are added in to brighten the color. The fabrics are constantly shifted and turned in the vats with long wooden sticks as the mixture boils for over 4 hours, deepening the color. The alum print ensures that when the fabric is dyed, only the alum printed areas retain the red color as it holds fast the dye, like a glue, to the areas it has been hand blocked on. The fabric is then washed in the river Baghini, rich in copper and other minerals. It is from its waters that the dramatic blood-red and iron-black motifs associated with the Bagh handblock printed textiles emerge. [gallery ids="165473,165474,165475,165476,165477,165478,165479,165480,165481,165482,165483,165484,165485,165486,165487,165488,165489,165490,165491,165492,165493,165494,165495,165496,165497,165498"] First published in Sunday Herald on 17th May, 2015.

By Design: Sustaining Culture in Local Environments

Issue #004, Winter, 2020 ISSN: 2581- 9410