JOURNAL ARCHIVE

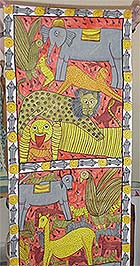

Introduction Pushpa Kumari belongs to the flourishing tradition of Madhubani painting which she learnt from her grandmother, Maha Sundari Devi, one of the pioneering Madhubani artists to work on paper. Selling from age 12, Pushpa’s uniqueness lies in her desire to experiment and develop new themes and treatments. She has pursued an artistic vision that derives greatly from the Madhubani tradition but which over the years, has been personalized with her own private preoccupations and quests. Interview At first glance, Pushpa Kumari looks like any other woman on the street, clad in a simple outfit, quiet and soft-spoken. Pause for a minute, look into her intense eyes and listen to her speak – suddenly you realize you are talking to someone exceptional, someone with deep spiritual moorings and immense artistic fervour. She has a strong and sure sense of herself, both as an artist and a person. Steal a glance at her intricate paintings and chances are that for a long, long time, you will not be able to take your eyes off her mesmerizing works of art. Her extremely fine black and white drawings are breathtaking, extremely detailed, mind-boggling in the complexity of line and form and yet beautiful and graceful in totality.

|

Life as a tree:- as it grows it also dries up and dies. Similarly as a human being attains another year in age, he loses that much of his life. Like the smoke disappearing into air, life also vaporizes. When the flames is put out only smoke is left. |

|

| The toddy palm gathers:- The life cycle of the Pasi caste Tapping the toddy tree. |

|

| Deepavali Festival |

|

| Cow & Bull being Mated |

Making palm sugar (gur):- Women of the Pasi caste engaged in making sugar from the sap of the palm tree.

Making palm sugar (gur):- Women of the Pasi caste engaged in making sugar from the sap of the palm tree. |

Mat weaving is an age-old cottage industry in India, with references dating back to the Atharva Veda (reference to kapisu or mats from grass). Indian folklore is also replete with incidental references in which the ancient sages were offered grass mats as seating. Mats made from grasses and reeds are abundant in India, especially in the more humid and swampy areas; local variations depend on the raw materials available and on other local conditions. The madur mats - made from the madur kathi reed (Cyperus tegetum and C. Pangorie) that grows in the swampy area around Midnapore in West Bengal - are the most popular of the mats produced in the state. The madur kathi grass from which these mats are woven grows particularly in the area around Midnapore, the coastal area of West Bengal west of the Ganges. Pranabes Das who along with his wife Saraswati Das weaves madur mats, says that the particular extent of the flooding in this area creating a particular kind of swamp condition - is what allows the madur kathi to grow here and nowhere else, for this grass needs a fairly specific amount of water. The overflooding in the three to four villages around Midnapore is not conducive to agriculture, not even to growing rice (which needs a fair amount of water). Thus, madur mats are specific to the Midnapore area.

textures, especially on the fine maslands. Otherwise, the green of the reed slowly fades to a pale gold as it dries with contact with air or with sunlight. Occasionally, natural dyes, made of mehndi leaves and other local plants are also used to created coloured borders; however, the madur mat weavers are so dexterous at creating colour vatiations and patterns using the natural colour striation of the madur kathi reed itself, that additional dyes are usually unnecessary.

textures, especially on the fine maslands. Otherwise, the green of the reed slowly fades to a pale gold as it dries with contact with air or with sunlight. Occasionally, natural dyes, made of mehndi leaves and other local plants are also used to created coloured borders; however, the madur mat weavers are so dexterous at creating colour vatiations and patterns using the natural colour striation of the madur kathi reed itself, that additional dyes are usually unnecessary.

|

This paper was presented at the 1997 Third International Conference on Design Education in Developing Countries, Technikon Pretoria, South Africa and published in Image & Text: Journal for Design (1997), Vol. 7, pp.3-8. It is reproduced here with the permission of the author. Brief SketchTechnology is often associated with the "magic and miracles of the glittering industrialized world" (Maathai, 1995). It is often seen as unattainable for the majority living in developing countries and the fact that it impacts directly or indirectly on every ones' lives is rarely acknowledged…. The producers of ethnic 'knick-knacks' in the South are caught in the developed / not developed "dualistic structure"(Plumwood: 43) so beloved by development theorists and practitioners….This paper discusses the current situation with regard to design, technology and development and the potential role for design of transforming technology from the unattainable and miraculous to the 'everyday'. The paper argues that the creativity of design can be used to perform magic that results in pleasurable and empowering technology. The status quo has to be challenged because as Plumwood continues to assert "once the process of domination forms culture and constructs identity, the inferiorised group ..[..].. Must internalise this inferiorisation in its identity and collude in this low valuation.." [I]t has to be recognised that 'universalism' and 'naturalism' can not be used to justify the status quo with regards to products designed and manufactured in the South. I am not suggesting that the production of handmade crafts be abandoned completely, or that it is in some way bad. Like technology, it exists in a globalised social structure and is only negative when seen as the 'other'. I am arguing for a pluralistic and creative approach to technology, one, or rather several, which may involve handmade artifacts, batch production, mass production etc running in parallel and occasionally converging. An approach which gives the producer and user control over what is being produced. As a designer, I perhaps not surprisingly believe product design practice has much to offer the transformation of technology. Not transforming through unattainable "magic and miracles" but by 'spilling' the secrets of the magic circle. Highlights

Section Titles of The Complete Paper |

|

INTRODUCTION |

GENDER, TECHNOLOGY AND DESIGN |

||

|

"OXFAM CATALOGUE SYNDROME" |

CONCLUSION |

||

|

PRODUCTION FOR MODERNISATION |

REFERENCES |

||

|

DESIGN AND DESIGNERS |

|

INTRODUCTION |

|

Technology is often associated with the "magic and miracles of the glittering industrialized world" (Maathai, 1995). It is often seen as unattainable for the majority living in developing countries and the fact that it impacts directly or indirectly on every ones' lives is rarely acknowledged. The observation that "common people and policy-makers alike [view modern technology] with a respect and wonder, usually associated with the occult", is also true for designers, (Saha, 1990). The South Commission (1990) suggests that countries of the South have consistently under valued the role technology plays in development and that a "sense of inferiority in the field of science and technology" is a fundamental problem. Here design has a critical role to play in making technology accessible at all levels. This paper discusses the current situation with regard to design, technology and development and the potential role for design of transforming technology from the unattainable and miraculous to the 'everyday'. The paper argues that the creativity of design can be used to perform magic that results in pleasurable and empowering technology. |

"OXFAM CATALOGUE SYNDROME" |

A number of non governmental organisations (NGOs) notably Oxfam, Traidcraft and others work internationally in the area of craft production for development as do several other organisations based nationally. These organisations produce catalogues to both promote their development work and sell the products manufactured by their projects. Oxfam is probably the best known organisation currently working in this field and I have therefore opted to describe the syndrome as the "OXFAM Catalogue Syndrome". However, the term is used generically throughout the paper. I would argue that design in countries in the South has been and continues to be trapped by the "OXFAM Catalogue Syndrome" (OCS). This syndrome has been derived from an observation made in the UK where several different catalogues promoting and selling articles from thermal silk long johns to microwaveable hot water bottles are received, usually unsolicited through the post or contained in the folds of the Sunday newspapers. In particular the Oxfam catalogue (or Traidcraft etc) arrives alongside the Innovations catalogue. The Innovations catalogue is packed with natty if often absurd technological gizmos for example electronic nasal hair removers, which are marketed along the lines of "transform your life! Indispensable! Time-saving!", which can be ordered through the post. The contrast between the two is highlighted by the difference in the running commentary each catalogue elicits. The Third World crafts achieve a brief "Oh this is pretty and would make a nice gift for…. " (fill in a relative for whom present buying is difficult) or "this must have taken a long time to carve, it's a bit expensive". In comparison the Innovations catalogue is poured over in detail with exclamations of "look what you can get now, clever isn't it" and even the extremes of technological irrelevance are grudgingly admired for the technical expertise, miniaturisation etc. The cost of the products is commented on but the expense is justifiable because of the amount of technology contained within.

As a consequence of these catalogues, the perception in the UK of what it is possible to design and manufacture in developing countries is tied to the Western ethnic 'knick-knack' market. I would suggest that the continued emphasis on producing artifacts for this market reinforces the "sense of inferiority" discussed by the South Commission because technology is largely absent in the production methods and completely absent in the products being offered for sale. The emphasis is on technology-free artifacts that are decorative first, useful second and devoid of moving parts be they cogs or 'chips'. It is argued that the observer can be made aware of the culture of the producer through a hand-made artefact or a visual image. However, with OCS, there is an inequality in consciousness between consumer and producer, a transformation of an artefact from meaningful object to one devoid of symbolism, (Brett, 1986; Sardar, 1993). Also present is the uneasy feeling of superiority on the part of the viewer. The impression of the 'other' is controlled and manipulated (Chowdry, 1995: 26). As we leisurely peruse the catalogue in the damp, grey UK, we imagine the exotic batik bedspread in our bedroom, the exquisitely carved coasters in our dining room and the expertly woven magazine rack at our feet in the lounge. And to cap it all we can supply our children with 'politically correct' wall hangings and t-shirts to counteract the effect of Barbie dolls and Game-Boys. Arguably this accessabilty to difference and the 'other' can result in greater understanding between cultures but what is being understood and where is the equality of understanding? Rather as Brett (1986) asserts this is the "commodification of aesthetic feeling and the imperialist assumption that the whole world is available". There is evidence of this in the introduction to the Autumn/Winter 1996 Oxfam catalogue. As a customer you are invited to:This begins to read like an introduction to a heritage theme park where tradition and culture are preserved and experienced through 'living' history. Both the romanticism of ethnicity and cultural imperialism become overwhelming. The relationship between the consumers and producers can be described further as a dualism, where as Plumwood (1993: 47), says it "is an intense, established and developed cultural expression of such hierarchical relationship, constructing central cultural concepts and identities so as to make equality and mutuality literally unthinkable". This is perhaps a harsh and shocking analysis of the relationship but the status quo has to be challenged because as Plumwood continues to assert "once the process of domination forms culture and constructs identity, the inferiorised group ..[..].. Must internalise this inferiorisation in its identity and collude in this low valuation..". Being technologically incapable, receiving the most patronising forms of 'appropriate' technology is the lot of the inferiorised. The emphasis on craft production for income generation and development is also part of this process of domination. Designers have a significant part to play in how technology is used for development. Noorgard (1995: 56) argues that "Societies, rather than picking and molding technology according to their values, are being shaped by technology". Countries in the South are being shaped by technologies the North deigns to allow them to have. This is not to suggest that given the choice the South would rush to adopt high-tech over and above the so called appropriate technologies but having the power to choose could optimistically lead to progress. I would suggest that it is here that design needs to be mobilised. Aesthetic, ergonomic and environmental considerations are all part of a designer's approach to technology (or should be!). Design is the interface between technology and people, and is therefore in some part responsible for the creation of identities and influencing cultural change . Design can be carried out in a participatory way again offering a bridge between people and technology, giving control over, rather than being controlled by technology. As Noorgaard (57) says "control [over technology] can only be exercised by each society developing a collective sense of self, defining its objectives, and thereby determining what progress is…"."choose from our exclusive range of hand-made products and food from around the world. Many of the products we have chosen for you reflect designs and materials that have been passed down from generation to generation, helping to preserve skills and age old traditions. Each of the hand-made items are unique, reflecting the touch of the individual craftperson."

Production For Modernisation

At the same time as design is caught by OCS, there is the paradox of production for modernisation through the manufacture of 'tradition'. Those who are producing the ethnic 'knick-knacks' are advised to do so to achieve development and ultimately, modernity. Whatever the liberality of cause espoused by the development / trade agencies involved in this production, they exist in and at least implicitly promote, capitalist market economies: the "goal of modernization theory" (Chowdhry, 1995: 28). Industrialised nations have not become so through the mass production of ethnic knick-knacks, but through the continued development of technology and products which utilise these technologies. Even where industrialisation has not been the goal innovation and design have been evident historically in the survival of the human race from agriculture to architecture, communication to travel. Products have not remained static so why in developing countries should they apparently come to a standstill in the name of 'development'? Buchanan & Margolin (1995: xii) argue that "design exists as the central feature of culture and everyday life in many parts of the world". However, the concentration on and promotion of ethnic artifacts has to large extent resulted in the tacit knowledge of design being lost through the "sense of inferiority" remarked on by the South Commission. The producers of ethnic 'knick-knacks' in the South are caught in the developed / not developed "dualistic structure"(Plumwood: 43) so beloved by development theorists and practitioners.

The cultural imperialism discussed above is also implicated in the control of technology and design. This is evident by the desire expressed in the North that "the Third World …avoid the wasteful and socially divisive path of marketing-led design in favour of socially useful products". As Whiteley (1993: 119) continues:The questions this raises are why are responsible design and market-led design seen as incompatible? And why should they be presented, as they usually are, as a dualism? I would suggest that this has been the result of the implicit cultural imperialism which continues in design for development. As we have seen above, the North perceives design in the South to be dominated by tradition and ethnicity. Design carried out in the North for the South is dominated by the image of 'appropriate' technology where this means solar power, fuel efficiency, basic needs etc. There are very few images of design being executed for the South by the South. The Ugandan design teacher, Pido (1995: 35) recognises that "There is a need to fit indigenous design to the cash economy" and suggests that "Design could blend skilled hand-production and domestic economic interest ….[to].. Produce consumer goods for ourselves." The key here is the production of consumer goods for the home market."The logic ought to be in favour of responsible design: Third World countries - almost by definition - are characterized by scarcity rather than surplus and merely owning a product ought, therefore, to matter more to people that its particular make or styling."

Design And Designers

Writers and practitioners from the South acknowledge that design is an "ancient activity" (Ghose, 1995: 193), and "an instrument of everyday life" (Pido, 1995: 35) but this 'everydayness' has resulted in both its invisibility and paradoxically its professionalization. The professionals live in the industrialized countries because I would suggest, design in many developing (and some industrialized) countries is only associated with craft production when it is considered at all. A vicious circle is beginning to become clear, one where the OCS can not be escaped from. OCS does not promote cultural diversity as it might first appear but initiates and sustains the dualism of tradition and modernity. The UNESCO paper (1988) on Human Resources Development, National Policies, Global Strategies and International Cooperation asks how "indigenous spiritual and cultural creativity [can be transformed] into initiatives and entrepreneurship" (in Cole, 1990: 374). This question needs to be asked of the development agencies and designers in the South should be the ones to do the answering. Ghose (1995) argues that governments will have to:

"introduce national design policies that will dovetail with developmental policies, thereby making design an agent of the visual manifestation of the ideologies of development. Thus, if the fundamental aim of the developmentalist is to provide national confidence and self-reliance and bring some sense of equity, visible symbols of this confidence will have to be shown not only in the styles of architecture adopted, but also in the materials and processes adopted, the manner of advertising undertaken, the styles of clothing exhibited, the nature of products manufactured, and the skill in converting modern imported technology into products distinctive for the specific needs of the people."

Ghose (1995: 188) suggests that indigenous design can not be separated from technology transfers, foreign aid and trade.." and obviously the reality for many governments of developing countries is that their hands are tied by 'tied aid', structural adjustment, loan repayments etc. As Ghose (2001) says "design and development is a quest for non-standardized answers in an age of standardization" .

Deforge (1995: 21) argues that technological objects have two functions, "utilitarian and sign". The technological component of an object gives it another dimension, often concealed and unconsidered. Design makes implicit and explicit decisions about how to use the technological component and if, as Deforge argues technology has always avoided ethical questions, it follows that designers have too. Responsibility is required of designers to ensure technology is put to honest, open use and not used to conceal inadequacies. Technology is too frequently proclaimed as a cure all; from clean and easy housework to clean and easy war, from solar powered stoves to smart bombers. The emphasis on technological developments, has suggests Eisler (1990: xx), been on destruction and domination and that it is this emphasis "rather than technology per se, that today threatens all life on our globe." Walsh, et al (1992: 49) point out that it is "very easy to ignore the wider consequences of design". This is pertinent to both the negative and positive aspects of design: It is easy to ignore the environmental consequences of the 'throw-away society' and equally easy to ignore the potential in design for creating positive change. Both require the designer to accept a degree of responsibility, move beyond their own personalised fantasies and seek the views of the potential users/customers. This is not to devalue the tacit knowledge which is "regarded as an essential component of the skills and quality of designers", but to suggest that design involves the potential users in the "product development process" (Walsh, et al: 50; 243). Walsh, et al (52) identify four "common features" in design practice which may provide a useful guide to understanding the role of design in the product development process. The authors refer to the following as "the '4 Cs' of design":"Creativity: design requires the creation of something that has not existed before (ranging from a variation on an existing design to a completely new concept).

Complexity: design involves decisions on large numbers of parameters and variables (ranging from overall configuration and performance to components, materials, appearance and method of manufacture). Compromise: design requires balancing multiple and sometimes conflicting requirements (such as performance and cost; appearance and ease of use: materials and durability). Choice: design requires making choices between many possible solutions to a problem at all levels from basic concept to the smallest detail of colour or form."

I would suggest that the four words; creativity, complexity, compromise and choice, have similar meanings in development where situations are often complex and require a creative approach to choice and usually result in compromise. The "4 Cs of design" could be used to emphasis the importance of the design process and the potential of technology.

|

Gender, Technology and Design |

||||||||||||

|

Another layer of inferiority is added by the remarkably globalised "cultural stereotype of women as technologically incapable" (Wajcman, 1994). The technical empowerment of women is vital to effective development efforts but whilst technology remains gendered so will it's inherent power (Stamp, 1989). Too many technological advances have resulted in women's lives deteriorating despite the "potential to transform lives…in a positive way." (Ng Choon Sim & Hensman, 1994). The role of designers is to package technology to make it accessible, desirable and usable to the people who live with and employ it (Dormer, 1991). Unfortunately, technology remains "both the social property and one of the formative processes of men" (Cockburn, 1994: 56) and designers are predominantly male. Consequently the people for whom technology is made accessible are usually men. As an inanimate object technology can cross international and cultural boundaries but as it does so it remains the "social property" of men and in many instances comes to represent "…the strongest force of male dominance [in] the public sphere…" (MacKenzie & Wajcman, 1994: 22). This is evident in military hardware, the electronics industry (where women are employed for their 'nimble fingers'), and water pumps (where men are trained to service them) amongst many others. One of the guiding precepts of design as it is taught and practised (certainly in the North), is that people buy particular artifacts in order to express and/or confirm their identity. If this the case then designers have a considerable part to play in defining the cultural system. However, unless cultural systems are redefined in relation to women, women will continue to be disempowered by technology. Technology will further entrench cultural "taboos" rather than negate them. Both men and women will be the poorer. Buchanan (1989: 98) highlights the problem of "technological reasoning, where beliefs and values always condition products, whether they are recognized explicitly, are implicitly assumed, or ignored completely". The belief that women are technologically inept is so ingrained that it is invisible never mind ignored. Once again this is apparent in the dualistic structures: culture/nature, modernity/tradition and developed/undeveloped. These dualisms provide a key to understanding the complexity of the relationships between gender, technology, design and development and how the OCS is involved in sustaining these relationships:

For a dualism to exist there has to be a relationship of dominance, one is seen in the terms of the other. The relationship of dominance implicit in the OCS is there both for women and men. There is an urgency to move towards 'multicultural' designers as Balaram (1995: 137) asserts "for designers to be convincing they too have to become involved with the object of design …. Only then can they expect to produce artifacts that are meaningful in the sense of reflecting the very mythology that guides users.." Equally there is an urgency to involve women in design, or rather recognise and validate the invisible design already being carried out by women (this is also the case in industrialised countries). Design carried out cross-culturally can add a layer of obscuration to technology for men and an additional layer is often applied for women. If, as Krippendorf (1995: 157) argues so eloquently product semantics goes further than "industry's immediate concern with production and consumption [because it is concerned with the] celebration of wholeness …the respect for mythology and archetypes that are rooted deep in the collective unconscious…", then the absence of cultural and gender diversity amongst global / international designers is an anathema. At the very practical level, the absence of women designers results in the "application of 'tacit knowledge' about women users' needs happen[ing] only rarely in product design" (Walsh et al, 1992: 244). Parpart & Marchand (1995: 17) highlight the role of the "analyst/expert" which they say "reminds us of the close connection between control over discourse/knowledge and assertions of power". The Northern design discourse is rarely 'bothered' by or with discourse from the South. Equally it is rarely concerned with women and/or gender, occaisionally chapters are written by women from a feminist perspective or feminism/women and design is mentioned by the male author (Walker, 1989; Attfield, 1989: Buckley, 1989; Whitely, 1993). In product design practice, design is only gender aware in so far as giving products masculine and feminine attributes for the differentiated markets. Of course what it is to be feminine is decided by male designers and as Eisler (1990: xviii) says "in male-dominated societies anything associated with women or femininity is automatically viewed as secondary …. To be addressed, if at all, only after the 'more important' problems have been resolved". I suggest that if design addressed gender seriously it would be able to fully understand that although professional designers have "long argued that..[they] represent the human being and the human dimension of product development" they no longer have to struggle to come to terms with the fact they do not "possess special knowledge about what people want and need.." (Buchanan & Margolin, 1995: xiv). Designs' creative energies could then be applied to possibly revolutionary ideas for development, both in the North and South. |

||||||||||||

| Conclusion Design treats women in much the same way as development is addressed, there is the patriarchal assumption that 'we' know best and as a consequence we rarely look at alternatives. Development agencies are adopting participatory approaches and dealing with issues of empowerment but design has a long way to go. At present design models are largely incompatible with those of development and consequently there is a lack of awareness of the issues by both parties. Through the OCS indigenous designers are being sold a model of design that is fossilised and can make no use of technological innovation. Production methods might be incrementally improved but the artifacts produced remain firmly situated in the tradition and decoration department and continue to be for export. Southwell (1995) has suggested that design could take a participatory approach, using and adapting a development model in order to improve the process of design. It could also help make those involved in development aware of what design has to offer. Also attention to the "4 Cs" discussed earlier could provide an accessible design discourse which, if used along side participatory methods, could help bring design and development together. A discourse that can be mutually understood is necessary if the work of designers is to "contribute more concretely and effectively toward a more humane existence in the future" (Rams, 1989: 113).Design is critical for the integration of technology into social structures, for making technology accessible and creating identities and consequently culture. Obviously technological progress has to be approached with caution to avoid the linear model highlighted by Norgaard (1995: 55), where "better science leads to better technology and more rational social organization and thereby to more material well-being through more effective control of nature". However unless technological progress is allowed to play a part in the products being designed and manufactured the current state of stasis will remain. It is also important to remember that tacit knowledge has to be allowed to develop or it too will stagnate. I would suggest that imagination is needed to explore the possibilities of technological integration, to break down the barriers built by the "OXFAM Catalogue Syndrome". Design could provide the method to do this.There has to be a recognition that technology is not a 'universalism' and that 'naturalism' can not be used to explain the status quo with regard to women's involvement with technology. Equally, it has to be recognised that 'universalism' and 'naturalism' can not be used to justify the status quo with regards to products designed and manufactured in the South. I am not suggesting that the production of handmade crafts be abandoned completely, or that it is in some way bad. Like technology, it exists in a globalised social structure and is only negative when seen as the 'other'. I am arguing for a pluralistic and creative approach to technology, one, or rather several, which may involve handmade artifacts, batch production, mass production etc running in parallel and occasionally converging. An approach which gives the producer and user control over what is being produced. As a designer, I perhaps not surprisingly believe product design practice has much to offer the transformation of technology. Not transforming through unattainable "magic and miracles" but by 'spilling' the secrets of the magic circle. | ||||||||||||

|

References Attfield, J. (1989) FORM/female FOLLOWS FUNCTION/male: Feminist critiques of design, in J.Walker, Design history and the history of design. Pluto Press, London & Colarado. Balaram, S. (1995) Product symbolism of Gandhi and its connection with Indian mythology, in V.Margolin & R.Buchanan (Eds) The idea of design: A Design Issues Reader, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London. Brett, G. (1986) Through our own eyes: Popular art and modern history. Heretic, UK. Buchanan, R. (1989) Declaration by design: Rhetoric, argument, and demonstration in design practice, in V.Margolin (Ed), Design discourse: History, theory, criticism. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. Buchanan, R. & Margolin, V. (Eds)(1995) Discovering design: Explorations in design studies. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. Buckley,V. (1989) Made in patriarchy: Toward a feminist critique of women and design, in V.Margolin (Ed), Design discourse: History, theory, criticism. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. Chowdry, G. (1995) Engendering development? Women in development (WID) in international development regime, in M.Marchand & J.Parpart (Eds), Feminism, postmodernism, development. Rouledge, London and New York. Cockburn, C. (1994) The material of male power, in D.MacKenzie & J.Wajcman (Eds), The social shaping of technology. Open University Press, Milton Keynes and Philadelphia. Cole, S. (1990) Cultural technological futures. Alternatives, 15, 373-400. Deforge, Y. (1995) Avatars of design: Design before design, in V.Margolin & R.Buchanan (Eds) The idea of design: A Design Issues Reader, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London. Dormer, P. (1991) The meanings of modern design: Towards the twenty first century, Thames & Hudson, London. Eisler, R. (1990) The chalice and the blade: Our history, our future. Pandora, London. Ghose, R. (1995) Design, development, culture, and cultural legacies in Asia, in V.Margolin & R.Buchanan (Eds), The idea of design: A Design Issues Reader, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London. Krippendorf, K. (1995) On the essential context of artifacts or on the proposition that "Design is Making Sense (of Things), in V.Margolin & R.Buchanan (Eds), The idea of design: A Design Issues Reader, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London. Maathai, W. (1995) A view from the grassroots, in T.Wakeford & M.Walters (Eds), Science for the earth: Can science make the world a better place? Wiley, UK. MacKenzie, D. & Wajcman, J. (Eds)(1994) The social shaping of technology. Open University Press, Milton Keynes and Philadelphia. Marchand, M. & Parpart, J. (Eds)(1995) Feminism, postmodernism, development. Rouledge, London and New York. Ng Choon Sim, C. & Hensman, R. (1994) Science and technology: Friends or enemies of women? Journal of Gender Studies, 3, 3, 277-287. Norgaard, R. (1995) Development betrayed: The end of progress and a coevolutionary revisioning of the future. Routledge, London & New York. Oxfam FairTrade Company catalogue, Autumn-Winter 1996 Pido, O. (1995) Made in Africa. Design Review, 4, 15, 30-35. Plumwood, V. (1993) Feminism and the mastery of nature. Routledge, London & New York. Rams, D. (1989) Omit the unimportant, in V.Margolin (Ed), Design discourse: History, theory, criticism. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. Saha, A. (1990) Cultural impediments to technological development in India. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 10, 8, 25-53. Sardar, Z. (1993) Do not adjust your mind: Post-modernism, reality and the other. Futures, October, 877-892. South Commission (1990) The Challenge to the South: The report of the South Commission. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Stamp, P. (1989) Technology, gender, and power in Africa. International Development Research Centre, Canada. Wajcman, J. (1994) Technology as masculine culture, in The Polity Reader in Gender Studies. Polity Press, Cambridge. Walker, J. (1989) Design history and the history of design. Pluto Press, London & Colarado. Walsh, V., Roy, R., Bruce, M.,& Potter, S. (1992) Winning by design: Technology, product design and international competitiveness. Blackwell, Oxford. Whiteley, N. (1993) Design for society. Reaktion Books, London. |

||||||||||||

|

CATEGORIES: Technology & Craft, Design & Technology, Women & Technology KEYWORDS: Craft, Design, Technology, Cultural Imperialism, Oxfam, North (Consumer)-South(Producer) Divide, Women |

|

With the onset of the new economic order in the early nineties, I believed that a special thrust had to be given to the craft sector to enable it to face the challenges of the coming decade. Crafts had to be looked at through hard economic mindsets rather than remain a part of a romantic-looking poster. This article was published in The Indian and World Arts and Crafts Journal in January, 1993 and reprinted in A Podium on the Pavement, New Delhi: USBPD, 2004. There are some favourite catchwords of the nineties which signify people's concerns and indicate an increased awareness of a new set of world values. Some of these are 'eco-friendly', 'women's issues', 'holistic development', 'crafts', 'vegetarianism' and 'organic' materials for health. These are a part of the concerns of those seeking more peaceful alternatives for survival in a world which continues to be overtaken by profit and poverty-poverty not just of the economic variety, but a depletion of the moral fibre of ideologies and of humanitarian concerns. Unfortunately, however, the real agenda is drawn up by those who speak of 'global markets' and a 'New Economic Order'. In this context it is important for all of us who are in some way involved in the propagation of our indigenous arts and crafts to shed the image of ourselves as the beautiful people of the crafts movement and see the situation as it really is. If we are prepared to do that we may manage to equip ourselves with enough commitment to convert our concerns into an abiding article of faith impinging on all spheres of our work and affecting all sections of our society. This alone will ensure the dignified survival of the craftspeople of India. The urgency of the situation is belied by the proliferation of craft shops, boutiques, bazaars and emporia in the more well-to-do neighbourhoods of the country. Crafts are more popular, handlooms are more fashionable-this is the impression created. But is it really so? How many craftspeople and weavers are benefiting? The data collected by the Operations Research Group, a Tata-owned organization which serves the mighty corporate sector, found that in 1989-90, 69 per cent of the total artisan households in India earned up to Rs. 750 per month, which works out to Rs. 5 per day per head in an average household of 5 persons. Among the minorities and the really poor, where a family includes elders and more than three children the situation obviously becomes much worse, only 0.3 per cent of all artisans earn Rs. 4,000 a month. Among rural artisans (who are much larger in number than the urban artisans), 29.6 per cent households earn only Rs. 350 per month, 47.9 per cent earn between Rs. 350 and Rs. 750, 19.4 per cent earn between Rs.751 and Rs. 1,500 and only 3.1 per cent earn Rs. 1,500 a month. That is as high as it goes. The craftspeople who come to the Surakund Crafts Mela, the Crafts Museum and the periodic bazaars are still only a chosen handful. Repeatedly buying the odd Tilonia chappal, Jawaja handbag or Sambalpuri ikat sari while thousands of roadside patterns, village weavers and deprived shoemakers go under because their markets have been taken over by the 'New Economic Order' must make us sit up and realize that there is far more that we have to do for the crafts and crafts people of India to survive as a thriving sector of a self-reliant economy. For this the attraction to handicraft and handlooms, the arts and folk styles of daily life must not just remain in the domain of the educated elite. Handicraft and handloom bazaars should not be popular just because we get 'arty' things at a fairly inexpensive rate but because health, environment, education, self-value, exposition of cultural diversity and other such vitally important areas are linked to the need for sustaining crafts. We need to get beyond the romantic and aesthetic to face the grim realities of what craftspeople are up against. For this we must draw in shoppers from a vast section of people and link their concerns with the crafts movement more directly. Let me demonstrate the ecology argument with a few examples. Take the kulladh - the earthen cup-made by our potters all over the country. With one crore passengers travelling by rail everyday, one lakh potter families would be kept at work daily if each traveller took just one cup of tea in a kulladh instead of a plastic or paper cup. The mud of the kulladh goes back into the earth without harming it. Hygiene is maintained by ensuring that it cannot be reused. Paper is saved and non-degradable plastic is avoided. Imagine the dimensions of a simple decision to use kulladhs everywhere-at every bus stand, canteen, cafeteria, roadside tea shop and, of course, the 'arty' restaurants? Not only the all-things-ethnic lovers but political parties, trade unions, schools, hospitals, offices and voluntary organizations across the country could lobby for implementation of this policy in their sphere of influence. Then it would be a real movement which would be difficult to destroy because there is simply no argument to do so. Economists should calculate how many kulladhs could be used in a day if all these organizations were to convert themselves accordingly. The employment thus generated would excel that of the corporate sector which is capital intensive and mechanized. Clay and fuel would be required but it is time that the potter's right of access to these should equal the access of industrial houses to materials required for paper pulp, yarn and various other products. How many craft-lovers and craft-users can channel their efforts into making this a reality? People connected with the large corporate sector would not just decorate their gardens or front lobbies with earthenware pots to show their love for crafts, but should see that in their entire sphere of influence everyone uses only the simple lowly kulladhs. It is when such objects are used as a matter of course rather than as a fad of the intellectual and social elite that the crafts of India will find their rightful place. The vanguard or catalyst role has, of course, to be played by this section of our society, to influence all other sections. The widening of our horizons as to what constitutes handwork will also help the crafts movement go forward immensely. Compartmentalised activity has in a way immobilized a concerted surge forward. For instance, for creativity to continue and encompass changing trends in society, traditional skills need encouragement to adapt and recreate rather than remain purist. Classical traditions in music, dance and theatre are lending themselves to modern themes, both secular and social, but crafts have not been helped to do so to the extent necessary or possible. Stone and wood carvers steeped in the tradition of making statues of god and goddesses, kalamkari artists depicting religious epics, mithila painter's familiar images can surely allow more space for secular or non-sectarian themes such as the glorification of Nature, equality of the sexes, care for the community, importance of the girl child, anti-dowry, anti-rape campaigns and the preservation of water and other forms of energy. Surely our craftspeople should make their skills relevant to mainstream issues instead of constantly glorifying only gods and propagating myths and superstitious beliefs. If those of us who are part of the crafts movement are shocked and angry with the destruction of the mosque at Ayodhya and the Shiv Sena attack on Muslims and all sorts of other 'outsiders' in Bombay, should we not guide our artisans to be relevant even outside the religious mindset? This is not to undermine the kind of sustenance religious festivals and establishments give to the artisan sector. For instance, the palm leaf baskets and tiny earthenware dishes with ghee wicks used or prashad and offerings at the Lord Jagannath temple at Puri keep thousands of potters and basket makers employed. Tomorrow, of course, the religious order may not be concerned if these are replaced by plastic and aluminium containers made in factories, but for the present at least, religious activity sustains artisanal activity quite unnoticed and unprotected by the doyens of the craft movement. Can we protect these markets or create new ones on such a scale? These are crucial questions require considerable introspection before they can be answered. Educationists also have a special role to play, for which the promoters of arts and crafts must make special efforts to encourage. There have been valiant but minuscule efforts at orienting unique and rich contribution the craftsperson can make if they are taught at regular schools. The spiritual value of handwork, the recognition of our aesthetic heritage an respect for this toiling section of society that goes beyond admiring them as museum piece curiosities are important seeds to be sown in fresh minds. If our children at school can spend a couple of hours a week talking to, and working under, the benign direction of an illiterate potter or weaver, the value of real education would be understood by them. Many simple scientific principles can be taught by craftspeople. Regional embroidery traditions could be learned by young school girls. Why should Archie comics, Walt Disney cartoons or Barbie dolls define the world of fun and entertainment for our children? Have we nothing to offer from our folklore which could be depicted by folk painters? It goes without saying that the use of regional languages as a medium is important if we want to spread the movement beyond the English-speaking dapper youth of our jhuggi jhonpri (slum) colonies take to Fido-Pepsi T-shirts and imitation Levis much faster than our children agree to go to a birthday party in handloom or khadi clothes once they are old enough to say 'no'. While we continue to expect government to formulate bold and far-reaching policies to help the craft sector; we should realize that the responsibility really lies with us. The minister in charge of handicrafts and handlooms has most often had the least clout in the cabinet, and could not possibly support the economic reforms being pushed through by the government to the obvious detriment of his portfolio; so he probably has to remain silent. Most ministers will promise help to diametrically opposed platforms and, in that kind of situation, the group with the most money or political muscle wins. It is never the crafts sector unless we become their effective vanguard, not just their buyers of baubles. When we influence the local teashop owner to switch to kulladhs, or force the imposing Krishi Bhawan to use handmade palm leaf waste baskets, instead of frittering our energies in symposiums, seminars and lectures, esoteric and academic, the crafts 'movement' will truly move ahead. |

|

While Americans in the northeast huddle in their thick winter coats and sweaters the European and America tradeshows are just starting to heat up for their first round of the year. Few consumers think or know about how the products they buy end up on the shelves and racks of American department and import stores, but these items have long lives before they reach the cashier counters and homes of Americans. This past January I attend the New York International Gift Fair and experienced a crucial part of this journey firsthand. The New York International Gift Fair occurs twice a year, once in January and again in August, and highlights some of the newest and hottest trends in home décor and gifts. The fair consists of six sections of products including general gifts, high-end design, museum store items, garden accessories, tableware and, of course, handmade. In the handmade section buyers can find a range of product from African wooden turned jars to Guatemalan hand-woven pillows. The fairs, a vital part of the marketing cycle in the United States, are a place where producers, exporters and importers can showcase new products to buyers. These buyers in turn place orders for products that will ultimately end up in stores and catalogs for some of the most popular chains in America. As I wandered the 18 miles of display area housed in one of New York's largest convention centers, I had a glimpse of the newest trends for this year. The products that are displayed in the most recent round of tradeshows were designed as long ago as six months and will not hit the store shelves for another six months giving artisans and producers enough time to fill large orders. These products also reflect a huge effort on the part of designer and product developers, who stay abreast of new trends in colors, materials, textures and patterns. These designers will help artisans develop new lines and collections that will be hopefully be favored in international, regional or local markets. This year I saw a tendency to geometric patterns, richer and deeper colors and a reflection to the past in terms of patterns and product shape. However, as a design consultant pointed out to me, there is also an emerging trend to use natural materials in their unrefined forms. This move away from refined, sculpted and treated natural materials reflects the use of cheaper, non-handmade components to replicate the look and feels of natural materials. One of the most vital components of the international market that artisans and designers have to be aware is the competition that factory made goods create. Goods from large factories in China, for example, use cheap labor, factory methods and inexpensive materials in order to produce items that seem handmade. These products are sold at extremely low prices and draw buyers, and ultimately customers, away from the more expensive handmade items. Because of this artisans need to keep their designs fresh and new in order to gain the attention of the international market. However, artisans can direct their products toward niche markets that require high quality and fair trade practices. These niche markets are often demanding and constricting with little leeway for new and learning producers. As an employee of Aid to Artisans I had the opportunity to attend the organization's Market Readiness Program which they hold biannually at the New York International Gift Fair. This training program, aimed at exporters and producers from developing countries, makes critical connections for people who rarely get exposed so fully to the American marketplace. The program consists of seminars, tours and product reviews, all given by seasoned consultants who have worked with ATA before. The seminar topics range from design trends to costing and pricing talks, giving producers and exporters a feel for the vast amount of knowledge needed to successfully access the American market. Of course this experience was eye opening for me as well giving me a behind-the-scenes look at the process of bringing craft from the artisans workshops to the buyers attention. One of the most exciting moments for me during my time in New York was witnessing and facilitating an actual interaction between an importer and a producer. By acting as a liaison between certain ATA contacts and our trainees I introduced a museum shop quality importer to a craft producer from Bolivia. This woodworker created beautiful and intricate carved animals painted in traditional, bright colors. And although the conversation between the importer and producer happen almost completely in a language I didn't understand, the excitement and sense of opportunity that hung thick in the air was enough to effect me. I walked away from that experience with a richer understanding of how craft can make its way from the small villages of a rural section of South America to the shelves of the San Diego Zoo museum shop to the mantles of American homes. |

Issue #002, Monsoon, 2019 ISSN: 2581- 9410 Few people are aware that the pre-spinning technology of cotton yarn making is damaging to cotton. After cotton from the fields is ginned in ginning mills, it is baled in steam presses for transport to spinning mills. Baling compresses trash such as bits of seed coat or leaf into the cotton and makes the soft lint into a hard, compact mass, like a block of wood. This hard mass has then to be unbaled and brought back to its original soft, fluffy state which in the spinning mill is done through the blow-room. By the time the delicate fibres of cotton have gone through these violent processes they are no longer springy but limp and lifeless and have lost a large part of their good qualities. A group of us realized this some years ago, and took up an experiment to spin cotton on a small scale in a way which would cut out some of the damaging processes and which would make yarn specifically for handloom weaving.

Issue #002, Monsoon, 2019 ISSN: 2581- 9410 In 2010, I was very fortunate to be awarded a ‘Making Space: Sensing Place (MS:SP) Crafts Fellowship’, part of the HAT (‘Here and There’) International Exchange and Residency Programme managed by A Fine Line: Cultural Practice. The MS:SP Craft Fellowship included a three-month residency programme for two artist-craftspeople from the UK, two from Bangladesh and one from India. The project offered time to undertake research and develop new work; experience and respond to museum collections, arte-facts, places and spaces; and offer opportunities to observe, work and collaborate with artists and craftspeople from the UK, Bangladesh and India.

Metal is a material I enjoy: the way it moves, its resistance, its feel, its weight, how it changes when heated, its shine, its smell, the sounds of it when worked…. Initial research for the fellowship identified specific things that I felt had a direct connection to my own practice as a metalworker and which I would welcome the opportunity to see and learn more of during the residencies. These included the stunning coiled silver neckpieces or torques called Vadlo or Vaidlah from Kutch in Gujarat, India and the ear pieces, sometimes of known as ‘Nagali’ earrings, which again come from the same region and make use of coiled gold or silver wire.

Metal is a material I enjoy: the way it moves, its resistance, its feel, its weight, how it changes when heated, its shine, its smell, the sounds of it when worked…. Initial research for the fellowship identified specific things that I felt had a direct connection to my own practice as a metalworker and which I would welcome the opportunity to see and learn more of during the residencies. These included the stunning coiled silver neckpieces or torques called Vadlo or Vaidlah from Kutch in Gujarat, India and the ear pieces, sometimes of known as ‘Nagali’ earrings, which again come from the same region and make use of coiled gold or silver wire.

During my time on the fellowship I was particularly drawn to the woven metalwork baskets, bronze casting and brass working traditions of Bangladesh as exciting areas of metalworking practice to explore and learn more of.

During my time on the fellowship I was particularly drawn to the woven metalwork baskets, bronze casting and brass working traditions of Bangladesh as exciting areas of metalworking practice to explore and learn more of.

Bangladesh is one of the poorest and most densely populated countries in the world. It is predominantly a rural country, with around 80 percent of the 160 million people living in rural areas. There are stark contrasts between life in the cities and life in the villages. Rural areas are often isolated with limited access to infrastructure or services. Much of the country is low-lying delta floodplain, prone to extreme seasonal flooding and cyclones during the wet season. Despite this hardship, Bangladesh has a rich and vibrant culture, including metalworking traditions that can be traced back as early as the first century BC.

Bangladesh is one of the poorest and most densely populated countries in the world. It is predominantly a rural country, with around 80 percent of the 160 million people living in rural areas. There are stark contrasts between life in the cities and life in the villages. Rural areas are often isolated with limited access to infrastructure or services. Much of the country is low-lying delta floodplain, prone to extreme seasonal flooding and cyclones during the wet season. Despite this hardship, Bangladesh has a rich and vibrant culture, including metalworking traditions that can be traced back as early as the first century BC.

There is sometimes a wealth that comes from poverty or hardship, the resourcefulness and ingenuity of people, particularly craftspeople, working with limited materials and resources, can often result in the production of highly sophisticated, informed and creative solutions to problems. During the course of the fellowship I have been excited and inspired by seeing creative communities and examples of the honest, inventive and creative ways in which craftspeople go about making work, with what seems like little or no resources.

During my stay in Bangladesh I had read about a small hamlet a short distance from the capital Dhaka where craftsmen had developed a process of collaborative hammer-working to produce brass, bronze and bell metal products; school and temple gongs, ritual dishes and engraved trays both for the home and tourist markets.

There is sometimes a wealth that comes from poverty or hardship, the resourcefulness and ingenuity of people, particularly craftspeople, working with limited materials and resources, can often result in the production of highly sophisticated, informed and creative solutions to problems. During the course of the fellowship I have been excited and inspired by seeing creative communities and examples of the honest, inventive and creative ways in which craftspeople go about making work, with what seems like little or no resources.

During my stay in Bangladesh I had read about a small hamlet a short distance from the capital Dhaka where craftsmen had developed a process of collaborative hammer-working to produce brass, bronze and bell metal products; school and temple gongs, ritual dishes and engraved trays both for the home and tourist markets.

With help and guidance from Shahriar Shaon, an artist and film editor, Shawon Akand, from CRAC (The Centre for Research on Art and Culture), Mokadesur Ahmed Tushil and Britto Arts I was able to visit the workshops to see if this craft tradition was still being practiced. Our journey took us by bus, auto-rickshaw, cycle-rickshaw and by foot. With each stage the pace of travel slowed, we came closer to the landscape and the surroundings became gentler on the eye and the ears.

With help and guidance from Shahriar Shaon, an artist and film editor, Shawon Akand, from CRAC (The Centre for Research on Art and Culture), Mokadesur Ahmed Tushil and Britto Arts I was able to visit the workshops to see if this craft tradition was still being practiced. Our journey took us by bus, auto-rickshaw, cycle-rickshaw and by foot. With each stage the pace of travel slowed, we came closer to the landscape and the surroundings became gentler on the eye and the ears.

Passing by people working in paddy fields, we walked along narrow pathways raised above the fields, heading for a small hamlet perched on a high earth bank. The man-made mound on which the cluster of buildings sat had been built to protect the properties from the annual floods during the wet season.

Passing by people working in paddy fields, we walked along narrow pathways raised above the fields, heading for a small hamlet perched on a high earth bank. The man-made mound on which the cluster of buildings sat had been built to protect the properties from the annual floods during the wet season.

Each year, during the dry season, the families dig clay and deposit it on the mound to raise the height or increase the size of the plot, in an attempt to protect the property from the rising waters during the monsoon rains.

Each year, during the dry season, the families dig clay and deposit it on the mound to raise the height or increase the size of the plot, in an attempt to protect the property from the rising waters during the monsoon rains.

We were drawn by the sound of hammering to a small workshop where a group of men were forging out flat discs of metal, stretching them to the required diameter, cutting the rims and forming the edges.

To get the initial disc of metal, the men cast a brass or bronze 'bell-metal' mix called 'pitol', from scrap. The scrap metal is sourced from old arte-facts and objects or is recycled waste and off-cuts from their own manufacturing process. The metal is melted in small crucibles made from river clay mixed with jute, rice husk and sand to give it its refractory properties and pre fired in the same charcoal and coke furnace used to smelt the scrap metal. The molten metal is poured into open shallow molds to make flat circular ingots approximately 15-20cm in diameter.

We were drawn by the sound of hammering to a small workshop where a group of men were forging out flat discs of metal, stretching them to the required diameter, cutting the rims and forming the edges.

To get the initial disc of metal, the men cast a brass or bronze 'bell-metal' mix called 'pitol', from scrap. The scrap metal is sourced from old arte-facts and objects or is recycled waste and off-cuts from their own manufacturing process. The metal is melted in small crucibles made from river clay mixed with jute, rice husk and sand to give it its refractory properties and pre fired in the same charcoal and coke furnace used to smelt the scrap metal. The molten metal is poured into open shallow molds to make flat circular ingots approximately 15-20cm in diameter.

Stretching these cast discs to the required thickness and diameter for the finished products is demanding work. Brass and the majority of its alloys are not very malleable and are hard to manipulate. The metal is prone to splitting and cracking when hot forged, especially if overheated or overworked. The men work together to share the physical workload.

Stretching these cast discs to the required thickness and diameter for the finished products is demanding work. Brass and the majority of its alloys are not very malleable and are hard to manipulate. The metal is prone to splitting and cracking when hot forged, especially if overheated or overworked. The men work together to share the physical workload.

In the workshop the men sit themselves around the edge of a sunken hollow. In the centre of the pit is a large metal post or ‘stake’ set deeply into the ground. Beside the depression is a coke hearth or ‘forge’ formed by a raised earth platform protected by sheets of corrugated iron and earth walls. A hand powered fan or ‘blower’ feeds air into a ‘pool’ of burning coke, increasing the temperature of the fire. Heating the metal makes the material more plastic, allowing it to be stretched and formed more easily.

Together, the men forge a stack of up to 8 of the ingots at a time working together to stretch the hot metal into thin sheets.

In the workshop the men sit themselves around the edge of a sunken hollow. In the centre of the pit is a large metal post or ‘stake’ set deeply into the ground. Beside the depression is a coke hearth or ‘forge’ formed by a raised earth platform protected by sheets of corrugated iron and earth walls. A hand powered fan or ‘blower’ feeds air into a ‘pool’ of burning coke, increasing the temperature of the fire. Heating the metal makes the material more plastic, allowing it to be stretched and formed more easily.

Together, the men forge a stack of up to 8 of the ingots at a time working together to stretch the hot metal into thin sheets.

See an overview of the workshop and the processes here:

http:/www.youtube.com/user/sj97dp?feature=mhum#p/u/1/KUDdqIJv6Pg

The way the men work is quite magical to see. The hammer-work develops in rotation as more and more of the men start to hit the metal. As each individual adds to the hammering sequence his first blow is struck then he misses a beat, indicating his addition to the order of blows, he then joins in at the faster pace. The finish is also signaled by a change in sequence of the hammering, some blows are placed to the centre and sometimes the direction or order of the blows is reversed or changed. The hammering continues until the metal is no longer hot enough to work, and the discs are returned to the hearth to be re-heated. The process repeats until the desired size or thickness is achieved.

See an overview of the workshop and the processes here:

http:/www.youtube.com/user/sj97dp?feature=mhum#p/u/1/KUDdqIJv6Pg

The way the men work is quite magical to see. The hammer-work develops in rotation as more and more of the men start to hit the metal. As each individual adds to the hammering sequence his first blow is struck then he misses a beat, indicating his addition to the order of blows, he then joins in at the faster pace. The finish is also signaled by a change in sequence of the hammering, some blows are placed to the centre and sometimes the direction or order of the blows is reversed or changed. The hammering continues until the metal is no longer hot enough to work, and the discs are returned to the hearth to be re-heated. The process repeats until the desired size or thickness is achieved.

The rhythm of the work is musical and the men use long and elegant hammers, designed to allow lots of blows to the metal in close proximity to each other and in quick succession. It is like a musical performance. Sound is key to the process, the sound of the metal and the stake varies from a dull ‘thud’ to a higher pitched ‘ping’ guiding both the individual with the tongs as to the angle and position of the plates he holds, as well as the craftsmen with the hammers and where they should place their blows.

Between each ‘heat’ the hammer workers sit and talk or undertake other tasks in the processing of the metal, such as cutting, forming, cleaning or engraving the discs.

The rhythm of the work is musical and the men use long and elegant hammers, designed to allow lots of blows to the metal in close proximity to each other and in quick succession. It is like a musical performance. Sound is key to the process, the sound of the metal and the stake varies from a dull ‘thud’ to a higher pitched ‘ping’ guiding both the individual with the tongs as to the angle and position of the plates he holds, as well as the craftsmen with the hammers and where they should place their blows.

Between each ‘heat’ the hammer workers sit and talk or undertake other tasks in the processing of the metal, such as cutting, forming, cleaning or engraving the discs.

When forged to the correct diameter the discs are trimmed and filed to a more uniform shape. The edge of each disc is marked out with a line from a set of dividers. An individual holds the marked disc at an angle on the side of a cast metal stake and positions a chisel, made of tool steel, along the line. The chisel is ‘handled’ with a piece of split bamboo, bound with wire. Another person acts as the ‘striker’, hammering the chisel into the brass plate to cut the edge. Again there is a fluid rhythm to the work, demonstrating both precision and co-ordination between the two men.

When forged to the correct diameter the discs are trimmed and filed to a more uniform shape. The edge of each disc is marked out with a line from a set of dividers. An individual holds the marked disc at an angle on the side of a cast metal stake and positions a chisel, made of tool steel, along the line. The chisel is ‘handled’ with a piece of split bamboo, bound with wire. Another person acts as the ‘striker’, hammering the chisel into the brass plate to cut the edge. Again there is a fluid rhythm to the work, demonstrating both precision and co-ordination between the two men.

The edges of the discs are filed and then formed either using a hammer over a smaller stake or working the metal into a depression formed in a stone, set into the workshop floor.

The edges of the discs are filed and then formed either using a hammer over a smaller stake or working the metal into a depression formed in a stone, set into the workshop floor.

Other workshops existed in the same hamlet and we followed the other sounds of metal being hammered and worked to discover a second workshop. Like the first, this space was of a timber construction clad with corrugated iron for a roof and with an earth floor raised above the surrounding ground.

Here the men were also working on the production of bowls and discs, there was clear evidence of the stages of production around the space, with small groups focused on a range of different tasks in the process – some were forging in the same way as those had been in the previous workshop, stretching out the cast discs of metal.

Other workshops existed in the same hamlet and we followed the other sounds of metal being hammered and worked to discover a second workshop. Like the first, this space was of a timber construction clad with corrugated iron for a roof and with an earth floor raised above the surrounding ground.

Here the men were also working on the production of bowls and discs, there was clear evidence of the stages of production around the space, with small groups focused on a range of different tasks in the process – some were forging in the same way as those had been in the previous workshop, stretching out the cast discs of metal.

Here there were examples of the crucibles, some filled and ready to be capped and heated for the casting process, others stacked ready to be filled. Stacks of large ceramic discs stood close by, these are the moulds where molten metal is poured to make the initial discs.

Here there were examples of the crucibles, some filled and ready to be capped and heated for the casting process, others stacked ready to be filled. Stacks of large ceramic discs stood close by, these are the moulds where molten metal is poured to make the initial discs.

Others were ‘planishing’ the cast discs, knocking out the worst of the dents and evening out the metal by hammering the plates onto the flat surface of a large stake. A part of the group were lined up along one side of the workshop engaged in scraping the surface of the discs smooth.

Others were ‘planishing’ the cast discs, knocking out the worst of the dents and evening out the metal by hammering the plates onto the flat surface of a large stake. A part of the group were lined up along one side of the workshop engaged in scraping the surface of the discs smooth.

Sometimes the scraping was by hand; using hardened steel blades set into a bamboo shaft. The sharp scraper is steadied by a steel bar both of which the craftsman holds together in his left hand and which are separated between his fingers and tensioned against the edge of the disc in his right.

Sometimes the scraping was by hand; using hardened steel blades set into a bamboo shaft. The sharp scraper is steadied by a steel bar both of which the craftsman holds together in his left hand and which are separated between his fingers and tensioned against the edge of the disc in his right.

As he works the scraper over the surface of the disc he releases the tension in his grip in the right hand, allowing the scraper to move, in a controlled way, with each successive movement, across the disc and towards the centre.

As he works the scraper over the surface of the disc he releases the tension in his grip in the right hand, allowing the scraper to move, in a controlled way, with each successive movement, across the disc and towards the centre.

The disc is held in position by three pieces of material. The first is a small stake in the ground with a slot cut into the diameter; this holds the base of the disc. The second is a stick, which again has a slot cut into it, and this supports the top of the disc. This is held in place by the weight of the craftsman’s left leg bearing down upon it. The third is a larger lump of wood / a brick or pad of cloth which sits behind the disc and supports it from flipping sideways or slipping backwards. The whole of the craftsman's body is used to secure and work the piece. The workload is very physical and the men's heels wear impressions into the ground. The scraping starts at the edge and moves toward the middle, the disc is rotated to work across the whole of the surface, producing interesting patterns as the marks, from the scraping, catch the light.

The disc is held in position by three pieces of material. The first is a small stake in the ground with a slot cut into the diameter; this holds the base of the disc. The second is a stick, which again has a slot cut into it, and this supports the top of the disc. This is held in place by the weight of the craftsman’s left leg bearing down upon it. The third is a larger lump of wood / a brick or pad of cloth which sits behind the disc and supports it from flipping sideways or slipping backwards. The whole of the craftsman's body is used to secure and work the piece. The workload is very physical and the men's heels wear impressions into the ground. The scraping starts at the edge and moves toward the middle, the disc is rotated to work across the whole of the surface, producing interesting patterns as the marks, from the scraping, catch the light.

The shavings from the brass that accumulate on the floor are collected and re-melted to make more discs. The scrapers are honed using emery type grit spread out on hardwood logs beside the workers. The men, as in most workshops I have seen in Bangladesh, work on the floor.

The shavings from the brass that accumulate on the floor are collected and re-melted to make more discs. The scrapers are honed using emery type grit spread out on hardwood logs beside the workers. The men, as in most workshops I have seen in Bangladesh, work on the floor.

Sometimes the scraping was done on an improvised lathe where the disc of metal is attached to a block of wood, which is, in turn, attached to machine made from bicycle components set into the workshop floor or attached to the structure of the workshop.

Much of the technology here is based upon work without electricity, only around 19% of the rural population has access to electricity, and even in the cities this is often interrupted by power-cuts.

The metal is held in place using heated plant resin as an adhesive. The resin is softened over a small ceramic kiln filled with burning charcoal, again heated with the aid of a small, hand powered, blower.

Sometimes the scraping was done on an improvised lathe where the disc of metal is attached to a block of wood, which is, in turn, attached to machine made from bicycle components set into the workshop floor or attached to the structure of the workshop.

Much of the technology here is based upon work without electricity, only around 19% of the rural population has access to electricity, and even in the cities this is often interrupted by power-cuts.

The metal is held in place using heated plant resin as an adhesive. The resin is softened over a small ceramic kiln filled with burning charcoal, again heated with the aid of a small, hand powered, blower.

When in position, the disc (and the resin) is quickly cooled using damp cloths. The resin hardens as it cools and this secures the disc in position. A stick with a metal ferrule at its end is used to make the disc run true. The left foot controls this, as both hands are occupied with the disc and the lathe. Once secured and centered a scraper is passed across the surface of the disc as it rotates.

When in position, the disc (and the resin) is quickly cooled using damp cloths. The resin hardens as it cools and this secures the disc in position. A stick with a metal ferrule at its end is used to make the disc run true. The left foot controls this, as both hands are occupied with the disc and the lathe. Once secured and centered a scraper is passed across the surface of the disc as it rotates.

See more of the workshops here:http:/www.youtube.com/user/sj97dp?feature=mhum#p/u/2/Ine5BEzxXWg

In the workshops there were between 6 - 9 men working together. They work collaboratively in order to be able to afford the costs of the materials and equipment and to share the physical workload. Producing the plates takes quite a lot of time and effort.

The men in the first workshop said that the dishes sell by weight, between 1000Tk - 500Tk per Kg depending upon the metal % mix. Plates weigh between 1 - 2 kgs,

See more of the workshops here:http:/www.youtube.com/user/sj97dp?feature=mhum#p/u/2/Ine5BEzxXWg

In the workshops there were between 6 - 9 men working together. They work collaboratively in order to be able to afford the costs of the materials and equipment and to share the physical workload. Producing the plates takes quite a lot of time and effort.

The men in the first workshop said that the dishes sell by weight, between 1000Tk - 500Tk per Kg depending upon the metal % mix. Plates weigh between 1 - 2 kgs,

The workshops sell their products through an agent, who sells at the wholesale markets in Dhaka. The agent provides the metal and pays the workers a making charge. The workers provide the tools and the fuel. In our limited discussions the comments from the craftsmen focused on the lack of machinery available to them.

I was struck by the ingenuity and invention, utilizing limited resources and collaborative working to overcome restrictions and limitations in the making process. It was clear that the metalworking processes these men used had developed in response to their environment and resources. There was very little wastage of materials through reuse and recycling. There was a beauty to the sound and the ‘performance’ of the metalworking process, but there was also an immense amount of time and labour that went into the making of these objects. The lack of power tools and mechanical processes made me rethink what the term ‘hand made’ really means and what the value of craft skill was and whether this method of manufacture was sustainable. It’s clear that Bangladesh is changing, I wonder whether the cultural shift in the capital and across the country will change the demand for the skills of these men and

The workshops sell their products through an agent, who sells at the wholesale markets in Dhaka. The agent provides the metal and pays the workers a making charge. The workers provide the tools and the fuel. In our limited discussions the comments from the craftsmen focused on the lack of machinery available to them.