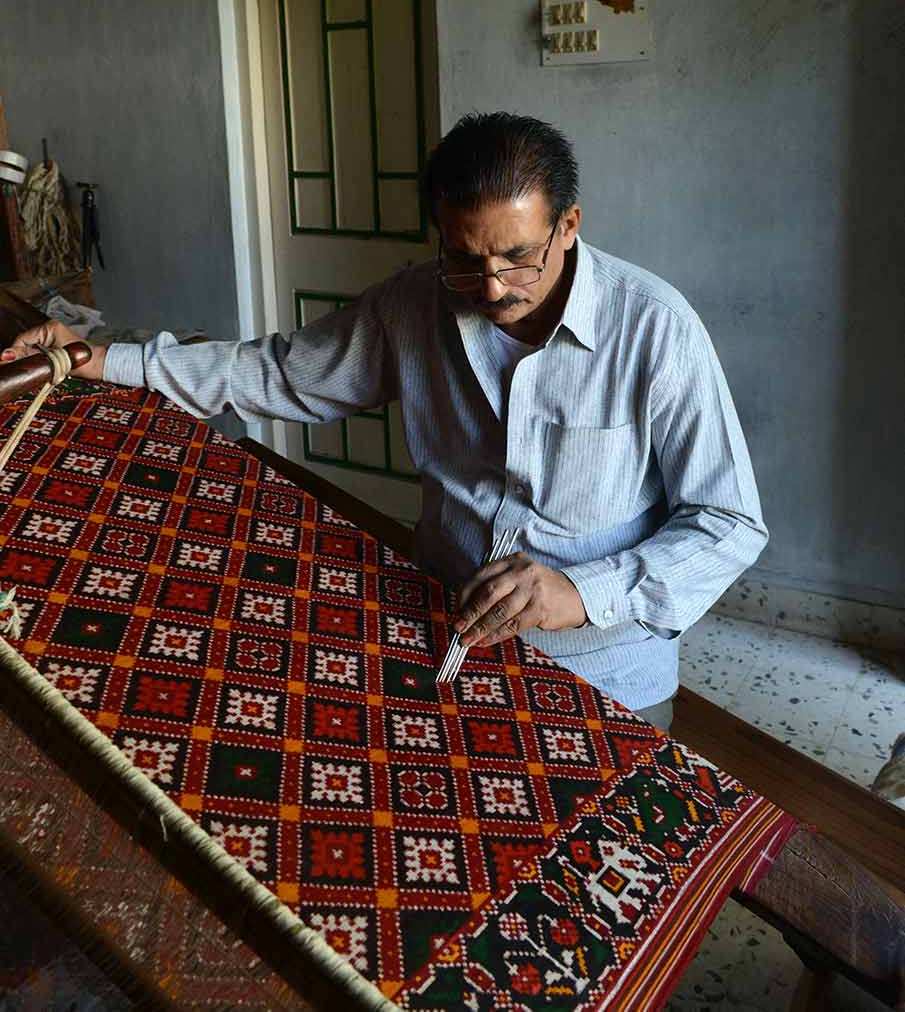

An artisan working on patola sari, Sam Panthaky/AFP[/caption]

An artisan working on patola sari, Sam Panthaky/AFP[/caption]

JOURNAL ARCHIVE

|

|

|

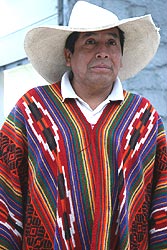

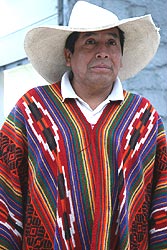

| We have to bear in mind that in Pre Incan time, numerous cultures were spaced throughout the territory, each with its own customs and traditions, working with whatever elements from nature they had at hand. These prevail to our time, making patterns and colours in jumpers and rugs distinguishable to different areas even now. The sierra is cold, thus using and extracting their base material, wool, from the “auquenidos” like the alpaca. (The auquenido is a camel-like animal, minus the humps) The coast-based cultures had no need for high cold resistant fabrics, using instead mostly cotton. Today, alpaca wool is still rich, warm and expensive; the animals pasture the high territory in the mountains and have their wool cut for the manufacture of chals, jumpers and chullos – a hat-like device that covers the head and ears. Baby alpaca wool is softer and even more demanded for its quality. Pima cotton is Peru’s best cotton, hand picked even today to avoid having the machinery tinting the white with yellow. The different use of colours in each region is due to the simple fact that e.g. a sierra flower won’t grow on the coast, or the colour of the soil in the jungle areas, called the “selva” is redder than the brownish coastal soil, thus each culture used whatever they had at hand for the fabrication of their textiles. | ||

|

|

| These images show products from an Indian market in downtown Lima, mainly wool articles from Huancayo, Cusco and Puno, all sierra territory. Today of course, many things have been modernized and are manufactured in factories, with many of the end products intended for export to the United States and Europe, where the market is rapidly growing. These tend to be family business, who maintain the base coloration and designs and of the region they came from. These designs replicate those made in ancient times and are meant to narrate a story, represent an animal which was considered divinity, show the path traveled by it’s people or show an ancient calendar, among others. | |

|

|

| The purses come from Arequipa and it's all hand sewn. The sewing is typically recognized as theirs, especially from the Colca area (which is one of the places where you can go see the condors in the early morning.) The condor has a strong link with Peruvian culture (songs, tales, etc.) The wall rug is describing a sierra scene, but it’s utility is different than the others. For starters, the details in it are sewn in high relieve rather than weaved and the colours used, bright green and pink, differ considerably from the usual. These are made by the sierra people, called “serranos” but who migrated to Lima. They are meant to show a scene in their life’s back home. | |

|

|

| The last textiles come from the amazons and are done by a tribe called the “Shipibos”. These are not meant to be exported, but rather are made just for recreation, which then end up in Lima for sale. The patterns made are random, whatever the person who made it felt like doing. It’s all hand painted using mud, flowers and the root of trees found in the jungle, giving the fabric a unique colouring and texture. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction Warli has been described as the art of the living. Unlike other folk traditions, it depicts not epics nor mythologies but the daily struggles and successes of the warli people, their lives dictated by climatic and seasonal changes. Austere in appearance, of stark palette, the paintings are neither. They are joyous and energetic, a celebration of life.

CREATING SHAADI KA CHOWKS

The warli women called Savasini meaning married women whose husbands are alive, paint a chowk or a square on their walls of their kitchen as they believe this is the most sacred wall in the house and therefore where the gods are placed. Before painting the wall surface is cleaned and polished, first with cowdung followed by Geru Mitti (red mud). The wall is polished by hand. With the help of a brush, the painter paints 'Shaadi Ka Chowk' on the polished wall and white colours are specially used for this. Apart from painting on the wall they are even drawn on clothes.

Availability of Raw Materials

| Nestling in rural Bengal, amidst the verdant paddy fields punctuated by picturesque pukurs (ponds) and grandiose antiquity, are entire weaver villages engaged in creating the equivalent of poetry on fabric. Triumphing over the trauma of partition, weaver families, which migrated to West Bengal in the 1950’s, have helped keep alive a priceless heritage of highly stylised weaving techniques honed over generations. |  |

| The handloom industry in the eastern region has had its share of bumpy rides, but Bengal handlooms have survived the ups and downs to become a household name among connoisseurs of handloom. | |

| Mr.S.K. Ghosh, ex director, D.C. handlooms, currently functioning as a consultant and resource person for the Handloom Cluster Development Scheme, accompanied me as a sensitive guide, specialist and activist, on my journey to discover the real face of handloom in Bengal and to gauge the response of weavers with regard to the new Cluster Development Scheme launched by the union government. |  |

| Speeding through lush green mustard fields set jewel like amongst banana plantations, we headed towards the handloom clusters in the district of Nadia. Across the river Churni, home to over seven lakh weavers, Nadia occupies a very important place in the Handloom industry in the State of West Bengal and the handloom itself plays a pivotal role in its socio–economic status. The traditional production of Jamdani Saree of Nabadwip, Shantipuri of Shantipur and Tangail varieties of Fulia area have been popular in the domestic market years together. For the uninitiated, there are at least six varieties of Bengal handlooms, each deriving its name from the village in which it originated, and each with its own distinctive style. The undisputed queen of the range, however, is the fabled Jamdani, which in all its myriad local avatars continues to retain its original grandeur and sophistication. The initial version is referred to as Daccai jamdani, although it is now also produced in Nabadwip and Dhattigram, in West Bengal. Daccai Jamdani is distinguished from its mutant cousins by its very fine texture resembling muslin and its elaborate and ornate workmanship. The single warp is usually ornamented with two extra weft followed by ground weft. While the original Bangladeshi sari is almost invariably on a beige background, the Indian weavers are a little more adventurous in their choice of colour schemes. It is woven painstakingly by hand on the old fashioned Jala loom, and many take even up to one year to weave a single sari. It feels supple to touch and drapes gently to reveal the contours of the wearer. While the Daccai Jamdani is strictly a formal affair, the other Jamdanis are much sought after by fashion-conscious women for their elegance and affordability. These are mostly replicas of Jamdani motifs on Tangail fabric and are generally known by the confusing nomenclature of Tangail Jamdani. Although beige background is the most popular, these are available in a riot of colours, at affordable prices. Besides Tangail, Dhoneokali, Shantipuri and Begumpuri are the other popular styles of Bengal handlooms in the lower price range. Of these, Tangail, which comes from Fulia, has a fine texture, with its 100s count fabric and highly stylised motifs, while Dhoneokali is known for its stripes and checks. Over the years, the distinctive patterns have merged as weavers started experimenting with various combinations of design and yarn, so much so, it is now difficult to distinguish between the various styles, unless one is a technical expert. Bengal is a large hub of Indian saree suppliers and manufacturers. Besides being sold as exclusive items in saree shops all over India, these are also exported to other countries. | |

| Ground Realities The enterprising weavers of Fulia, have organised themselves into Self Help Groups that go by the common name of Fulia 1, 2 and 3. Mr. Amulya Kr. Basak, Manager of Tangail Tantujibi Unnayan Samabay Samiti Ltd, fulia no. 2 is an affable gentleman with an honours degree in Mathematics. The Samiti has currently 558 members and functions as a nodal agency between its members and the rest of the world. The three Fulia Samitis collectively have an export turnover of almost 15 crores approximately. Their main buyers are based at Italy, Japan and France. The domestic turnover is however around five crores. |  |

| Interestingly these groups do not export directly but procure and deliver orders to various ‘agents’ in and around Kolkata. As a matter of convenience, the big buying houses appoint these agents/merchants who in turn get the fabric woven by the weavers. The weavers therefore work with a reduced profit margin of a mere 15%. | |

| Mr. Basak expressed his desire to increase profits so that they could attain long term sustainability in direct export marketing. Another drawback of the existing arrangement was that the merchants in search of a perfect price had a tendency to source the goods from a variety of weavers or even distribute the order to other weaving centres like Benaras etc, thus making the prices and products more competitive. Therefore the Cluster Development Scheme’s focus on exportable items needs to be reviewed in light of this phenomenal loss of profit suffered by the weavers due to middlemen and duplication by other weaving areas. |  |

| As I walked around Fulia no 2, one saw a lot of activity, with woven fabric, scarves and sarees being received from members as well as yarn issued out to those wanting to take back fresh work. The cotton yarn currently used is procured from NHDC while the silk used is from Bengaluru and China as well. The Chinese yarn needs to be made into smaller hanks for better dyeing. |  |

|

One also saw hand spun 200s count Khadi yarn being prepared for degumming and scouring. This was procured from the nearby weaving area of Murshidabad, which traditionally is a stronghold of Khadi spinning and weaving. Although, Murshidabad is only a few hours away, the price quoted by the Fulia weavers for Khadi fabric was much higher than that of similar fabric from Murshidabad. |

The dye house was well equipped with an exclusive room for Natural Dyeing.

This technique was re-introduced into the area only a few years ago. Mr.Ghosh, displayed with great pride an extensive shade card of colours that could be produced locally, if the need arose. Currently Natural dyeing had been suspended for lack of orders.

|

| Design The TEXTILES COMMITTEE is looking after the Fulia cluster & Shantipur cluster. Mr. Saumen Mapdar is the Cluster Development Executive and senior quality assurance officer. He along with Mr. Debashish Shome, another technical expert from the Textiles Committee was present throughout my visit to Nadia. Mr. Mapdar was currently working on a layout of carry bags displaying the strengths of Fulia, while everyone enthusiastically suggested a variety of slogans that could be used as ‘catch phrases’ to represent this weaving area! As he candidly pointed out, they were there to assist the weavers to not only market themselves better but also provide improved technological support. |  |

|

Another prerequisite of the cluster development scheme is the presence of a ‘directory’ of traditional designs that can be used as a reference point for designers and buyers. These need to be collected by the Implementing agency through the effort of its Cluster Development Agent. My inquiry with respect to this yielded an exchange of furtive looks and an explanation that such an exercise had not been conducted since the cluster was a recently formed. However I was assured that my pending, subsequent visit to weavers’ houses would surely reveal some of their traditional design wealth. |

| The ‘export’ design repertoire of Fulia No 2 was pleasantly exhaustive and impressive. Their ‘Buyer’s Room’ was well stocked and nicely displayed. A variety of fabrics were visible – linen and silk scarves, attractive silk stripes, single indent cotton pieces, extra weft designs, Jacquards, embroideries (machine, and I wondered WHY?), Sari designs translated into scarves and many more combinations. The effort and sincerity of these weavers to evolve was visible and impressive. My only regret was the lack of a sustained effort to maintain a cultural identity that stood witness to years of traditional weaving expertise. |  |

| Although the domestic section had a variety of saris and designs in a plethora of colours and weaves, yet the perfect amalgamation of form, colour and function, blended into a symphony of Universal design, that is traditionally the strength of Indian aesthetics was painfully obscure. |

| It appeared that the Fulia weavers were already on the roll through their own enterprise, and one couldn’t help wondering how and where the Cluster Scheme would intervene in this cluster and whether there was a specific road map that was being followed. Answers to this question were non-specific and the plan was to follow the general guidelines of the Cluster Scheme. Some interesting and vibrant designs of scarves and sarees were seen at the office of Shri R.N Basak, who was once a member of the Fulia consortium but separated a few years ago due to ‘political’ reasons. He now weaves for some well know designer labels and even claims to have woven the ‘chhatri’ used during Priyanka Gandhi’s wedding. |  |

| A lot of talk about the cluster scheme and its benefits seem to emanate from its strongest votaries by default – those associated directly with implementing the scheme. The gentlemen accompanying me were the only visible references to some activity related to the implementation of this scheme, flaunted much as the trump card of the current union government. The general opinion about it varied from being vaguely hopeful to downright dismissive, as the weaver populace seemed in the grey and a bit unsure of its success. |  |

|

The local weavers have no time to waste in idle gossip. They had to finish what they were weaving so that they could get their wages of Rs 120/- to Rs 180/- per sari, depending upon the design. While the men were busy at the looms the women besides them alternated their chores between tending to the children and being actively involved in the pre and post loom processes. |

| Although these ladies assist the men in weaving delicate dreams, they themselves wore cheap printed polyester saris. Only the wives of the affluent master-weavers were seen flaunting their home produce. |

| This was nowhere more apparent than in the nearby town of Shantipur, where seven master weavers with about 350 looms approximately had just set up a consortia with a total turnover of Rs one crore. Infact the members of the Textile Committee accompanying me were visiting the area for the first time since the consortium was set up. |  |

|

Presently the traditional Shantipuri Sari is only marginally different from that produced at Fulia. For differentiation, I was shown a ball of wet puffed rice that is used to finish the Fulia sari while in Shantipur it is saboodana starch that is used. Here weaves, counts and designs seemed to have merged into each other to produce confusing products and even more bewildering nomenclature. |

| However, zari, viscose and nylon yarns were used with greater panache in this area. The most revealing and an example of the direct intervention of the cluster scheme was visible when I was shown by hopeful hands a few ‘new designs’ developed by them as directed by the Designer in charge of this cluster. These were silk cushion covers in shades of grey and brown. On their own these looked ordinary and could have been woven in any part of India – Benaras, Bengaluru etc. Where was the strength of Shantipur reflected in these? Besides why was a traditionally and predominantly cotton weaving area concentrating on weaving silk, while its core strength still remained un-exploited? These issues when aired met with a stunned silence. Mr.Ghosh stepped in to make these simple souls aware of the highly competitive and cutthroat export/ external market. He explained that the looms needed special reeds to work with the finer silk yarns. The cost was higher and greater risk involved. It was suggested that they work around their very own ‘Shantipuri designs’ maybe in simple tonal colours to start with. The general complaint was a lack of the physical presence of the designer coupled with an incomplete and vague design brief used as a reference by the designer himself. |  |

|

A small shed was being constructed in the village to accommodate a few looms and also function as the office of the consortium. Mr. Ghosh with his vast experience pointed out a major flaw in the new looms. His prompt and wise intervention made me marvel of the merits of such schemes, which although difficult to implement, could be precursors of transformation for those involved. |

| Without passionate dedicated officers the cluster scheme has the danger of disintegrating into yet another ambitious idea. And, it goes without saying that the products that are representative of its good intentions should also reflect them. Thoughtful, controlled and sensitive intervention was the key for its success. |

| My final stop was the Shantipur Kutirpara Co-op Weavers Society Ltd., one of the oldest weaver’s co-operatives. The mood here too seemed indifferent to the magic of the cluster scheme. The ground realities appeared to cloud any hopes of a magical turn - around through governmental intervention. As we sifted through their many samples highlighting the cluster scheme, the office bearers of the society busied themselves in dispensing weekly wages to their weavers. Amidst a cacophony of voices, as views were parried and ideas exchanged for and against the merits of the cluster scheme, language seemed only a barrier for the mind, the heart understood everything - their hopes, expectations, concerns and despair. |  |

| A silent resolve to continue our ‘Tuesday collective’ (an informal group comprising of Mrs. Kasturi Gupta Mennon, Mrs. Ritu Sethi, Mrs. Gulshan Nanda, Mrs. Rathi Vinay Jha, Mrs. Jasleen Dhamija and the baby of the group i.e. myself) efforts to be a truthful voice for these original masters of fabric and fantasy took root in my mind. I realised that only honest intentions and the ability to translate them into true action could create a force that might inspire these simple folks to continue and sustain their time-honoured traditions. This seemed imperative as ghosts of urban confusion garbed in ‘latest’ combat denims, slick tee shirts and garish georgette saris, humming nasal Himesh Reshammiya numbers threatened to take over the rural mindscape. Late in the evening as the warmth of the day gave way to the uneasiness of a cold night, the rustic landscape morphed into unnamed and unrecognisable shadows, sliced through rudely by our speeding vehicle. As I watched their mesmerising play, I realised that for our enterprising craftspeople the scarcity of resources or the hardships of daily life never acted as real impediments to their growth. For them life was tapasya, a penance to transcend the ordinary to experience the extraordinary. It was this extraordinary that manifested through their deft fingers to give a taste of bliss to both the creator and consumer. Today, unabashed and uncontrolled alien influences are making inroads into their sacred spaces leading to conflict, confusion and degeneration. It is these tamasic intrusions that we need to filter so as protect and prevent our traditional crafts and handlooms from decay. A movement to reconnect to all that is essentially Indian and truthful is the only way to regain and re-establish their past glory providing a conducive fertile ground to nurture the future. |

Discussion on India’s handloom heritage swings between extremes. Some influential minds would have us believe the fabric is doomed to extinction, given the versatility, speed and economy of computerized production on powered looms. A contrasting conviction is of millions dependent on India’s second largest source of livelihood, serving a huge market at home and abroad, and creating what for some is ‘the world’s greatest fabric’. There is another argument, less heard yet probably of greatest import. It regards the handloom as symbolic of an alternative paradigm of human development, placing human and planetary wellbeing at the centre of concern. In this perspective, the Indian handloom is more than a tool. It emerges as a composite world view, as a culture, and as resource of wisdom and innovation that can respond to contemporary challenges with extraordinary creativity. A middle path must find its way through the debate and into the market place, where the user is judge and jury. So, who needs or demands hand-made fabric? Can demand be built over competition from mass-produced imitations and alternatives? What does ‘handmade’ actually mean in this age of mixed skills, materials and technologies? The answers should belong to the buyer and the weaver, yet both voices are stifled. The extinction argument is the one proclaimed loudest, by lobbies claiming to speak for the consumer, yet without any mandate from her. Their political clout is not matched by activists and aesthetes, inspired by the ‘charkha century’, or by the discipline of alternative economics that is largely unaware of the craft sector’s antidote to jobless growth. Research-backed, demand-driven handloom strategies are nowhere in sight. The sector’s last marketing genius was Gandhiji. He changed the tastes of a nation through a handloom revolution that gave the last century its grandest design story. That message echoed after Independence. Pioneers like Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay and Pupul Jayakar made the hand-made indispensable to defining who we are and who we want to be. That is, until globalization and ‘liberalization’ cloned Indian dreams into Shanghai and Silicon Valley fantasies. The handloom became an embarrassment when technology could deliver facsimiles at fractional cost, and to uniform, mass-market standards. In shops stacked with mass-produced imitations, few discerned the difference. So why care? Heritage should now move off the body and into museums. These arguments led a few years ago to an outrageous decision (fueled by lobby pressure to scrap the Handloom Reservation Act 1985) to fix electric motors on handlooms. The announced intention was to reduce drudgery, lift earnings and liberate the poor weaver. At one stroke, millions of handlooms would become power-looms and heritage skills lost, perhaps forever. India’s weavers suspected crocodile tears. Protests across the country finally led to a PMO assurance that handloom definition would “remain in the purest form”. Soon, a handloom blitz was launched from Varanasi, a new Prime Minister’s constituency and home to the ultimate symbol of India’s craft genius. Fashion galas have followed, all with the objective of ‘lifting global handloom demand’. Politics has forced the doomsday scenario into the wings. There, its whispers continue unabated. Market demand is and will remain at the heart of this issue. Given the scale of the industry and the market, the absence of serious research over almost seven decades is truly astounding. A fabric some consider the finest and others regard as terminally ill has been produced, sold, imitated, dumped, defended and promoted at highest levels without clear demand evidence or supply response. At a mega Mumbai event, a design icon demanded to know why all the fuss? There was, she claimed, no lack of demand for handloom quality, either at home or overseas. “There is zero resistance on price. Buyers pay for quality. I can sell whatever I make, and I can sell it all at home. I don’t bother about exports”. Her constraints were all in the supply chain, and in the appalling poverty that claims most Indian artisans. Bottlenecks in yarn delivery, transportation, poor market knowledge creating confusion on consumer preferences, inadequate access (to credit, design, IPR and technical services), a Reservation Act that is seldom implemented, dumping from East Asia, dreadful conditions of work and living --- all offered testimony to decades of schemes that have failed to deliver. The need was management, not 5-star hoopla. If the future is a land we cannot visit, another generation of weavers must resolve the argument. Some are indeed exercising the option of exit from a hereditary profession. So do their peers elsewhere. Others long to remain in the tradition of their forbears, but with hope and dignity. Both demand new knowledge and access to its sources. Investment in entrepreneurship is a first essential. Professionalism could at last bring an end to the dreadful tradition of handloom fabric promoted as a rebate opportunity, signaling a product to be bargained down and treated as charity, not as ‘the world’s greatest fabric’ with USPs that youth can recognize as simultaneously economic, social, political, environmental, cultural and even spiritual. And not just at the high end: the humble gamcha has a hugely profitable local market. Cynics continue to suggest that anything the hand can do technology can do better, even as jobless growth stares India in its face. Should this argument be used to dismiss other advantages of hand, eye and mind? Indigenous knowledge is increasingly respected as India’s priceless intellectual capital in agriculture, water, health, well-being, education, housing, combating climate change and in the arts. If technological and managerial advances do not torpedo other sectors of Indian creativity, why stop at weavers? They have welcomed change, innovated technologies and served global demand for centuries. Why assume that the great textiles of the future will not emerge from those who created the greatest 20th century fabric? If cutting-edge indications are needed, listen to Nandan Nilekani: “Our mental models are outdated. Export led growth, ‘make in India’ and big firms are yesterday’s stories. The future lies in our domestic market….. In the new world order everything is micro, millions of small procedures aggregating their capability by using technology”. That is a truth young weavers across the country recognize. It is the opportunity they are demanding. It should be theirs. First published on July 16, 2016.

| Tihar Jail Complex in New Delhi is one of the largest prison complexes in the world with a total population of around 12,610 prisoners. In a year about 70,000-80,000 prisoners remain lodged in these prisons for different duration. This prison population includes about 531 women prisoners with about 51 children below 6 years of age dependent upon them. | |

Tihar Prisons have a history of reformation programmes in tune with the current correctional philosophy. Education, Cultural activities, Vocational activities and Moral Education etc. have been going on in Tihar Jails for a long time as a part of the efforts of the Prison Administration for reformation of the prisoners. In the last five years the process has accelerated and received world wide attention. The reformation package tried out by the Delhi Prison Administration is popularly termed as "New Delhi correctional model", the basic characteristics of which are:

|

|

Tihar Jail is famous for the production of a variety of goods at its factory in Jail Number Two. The factory - a fully modernised and computerised unit - engages convicts productively in various activities like tapestry weaving, carpentry, chemical-making, paper making, tailoring and baking. Many of these reforms were initiated by Kiran Bedi while she was the police chief at Tihar from 1993 to 1995. One such project was to teach the women inmates weaving techniques.

The Project: WEAVING BEHIND BARSPeriod: 1994 - Team: PRIYA RAVISH MEHRA Sponsors: DANIDA (DANISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE) FROM THE ROYAL DANISH EMBASSY, NEW DELHI |

|

| Objectives Train the women inmates at Tihar weaving techniques and processes primarily as a medium of self expression and secondly an additional vocational skill which might be applied after their release. The intent was therapeutic. It aimed to empower the women socially, emotionally and economically. | |

|

In 1994, following an exhibition of her work at the British Council, Priya Ravish Mehra was invited to establish a tapestry weaving training program at the Tihar Jail. She maintains that tapestry weaving is an extremely introspective and meditative process. The fundamental characteristic of tapestry weaving is a simple frame on which weaving develops upwards - it is an open creative journey up the warp, one which she felt would channel the inmate's emotions and creativity slowly and methodically. |

| Priya began by presenting her work at the jail and gauging the interest of the inmates. Of those who attended the presentation and showed an interest in the program, twenty were selected to undergo training for three months. During these three months they were given a monthly stipend as an incentive to finish their training. The aim was to make the inmates self-reliant so that even if Priya left, the knowledge would be contained within the community and taught from inmate to inmate. Due to the strict rules on what might be used or brought into the facility, Priya had to devise simplified looms which did not contain nails and could be used to spin by fingers as needles and shuttles were banned. Each trainee was given one loom to work on. These were movable so the inmate could weave both indoors and outdoors. Workshops and classes were held on alternate afternoons for duration of three hours. | |

| Though the objective was not only to create professional weavers but to create modes of self-expression many women should surprising skill, dexterity and aesthetic sensibility. It led the project leaders to organize an annual exhibition of the weaves at the Danish Ambassadors residence where the larger public appreciated and acquired the pieces. From the pieces sold, after the cost of material was removed the profit was placed in the bank account of the weaver inmate. |  |

| After the initial twenty women were trained they have continuously passed on their knowledge to the other inmates. Each weaver is provided with her own loom. The program continues though Priya's involvement stopped in 1997. She found that the level or lack of education did not affect the quality of the work produced. She imparted the most basic weaving knowledge so has not to hamper the imagination of the women. She learnt that because these women led such regimented and controlled lives projects like Weaving Behind Bars helped them to function beyond their assigned space, to live outside the walls. For further information please contact Priya Ravish Mehra at [email protected] | |

It is said that “the best teacher one can have is necessity” and no doubt, man has learnt from nature the beautiful art of inter working indigenous materials to create objects for his personal use and existence. Stretches of tall grasses growing all over the world and providing sustenance to animals, birds and insects also stirred the imagination of man who, taking a clue from innumerable examples offered by Mother Nature through the intricate weaving of nests by birds, gossamer webs by spiders, the natural criss-cross weaving patterns of branches of trees, leaves and twigs, and the intertwining of grasses and reeds, saw possibilities within the reach of his nimble fingers to use the abundantly growing vegetation to make baskets, mats, ropes and what not.

Abstract Urmul Marusthali Bunkar Vikas Samiti (UMBVS) is a community-based organization that has succeeded in improving the social and economic status of handweavers in villages of Western Rajasthan. This article gives a narrative account of the formation of UMBVS and the changes in circumstances among traditional pit loom weavers who have joined UMBVS and received training in the weaving of new products for urban markets. The vision and persistent efforts of key leaders have helped UMBVS to thrive despite many challenges, not only in product and market development but also in generating the trust and participation essential to community development. The article includes the background of chief executive Ram Chandra Barupal whose commitment has helped weavers break the constraints of poverty. The author's experience at the Urmul Phalodi Weavers' Centre and nearby villages conveys the atmosphere of the place and the voices of the people. Weaving New Freedoms in Rajasthan Proud and industrious artisans were once the backbone of Indian economy, providing much of the goods and services that our people needed. Today these artisans have been marginalized by the modernization and industrialization of society. Though some have managed to adapt to changing times and a few have even thrived, most of them live in abject poverty with no hopes for a better tomorrow. (1995, Status Report of India's Artisans) Urmul Marusthali Bunkar Vikas Samiti (UMBVS) is a grass roots organization in rural Rajasthan that is well-known in India for improving the economic status of handweavers and contributing to the survival of traditional crafts. In a relatively short period of time, UMBVS evolved into a hriving community- based organization by building on traditional crafts skills and knowledge and bridging the gap between rural artisans and urban consumers. As a consequence of integrating craft and community development weavers and their families are finding new freedoms and possibilities. UMBVS is one among many craft development organizations in India that are confronting the enormous challenges of establishing sustainable employment within viable craft communities. To name but a few others: Dastkar Andhra in Andhra Pradesh, SEWA Luchnow in Uttar Pradesh, REHWA Society in Madhya Pradesh and Jawaja Weavers' Association in Rajasthan are several examples of organizations that address the needs of handweavers and help create conditions for sustainable social and economic development. It is my intention in this article to examine one such organization. I focus on the story of the Urmul weavers, including, the emergence and development of UMBVS, the role of chief executive Ram Chandra Barupal, and events I experienced during my visits to weaving villages. The common aims and challenges among different craft development organizations will be pursued in another article. Journey to Urmul Phalodi I arrived in Jodphur, Rajasthan, with my husband after an eleven hour overnight bus ride, 526 kilometres northwest of Ahmedabad in the state of Gujarat. The next morning David and I travelled four more hours by train to Phalodi, 125 kilometres away. We sat on wooden enches; open windows let in the warm November air. Going west from Jodhpur we entered a vast expanse of sparsely vegetated land. We passed dry cultivated fields and sweeping sand dunes and the train stopped at each town along our route. Men in white dhoti's and turbans and women in colourful saris sat with us on the train. I had arrived for my first time in India nine weeks earlier to begin research sponsored by a fellowship from the Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute. My intention was to investigate community- based initiatives that support the continuity of handweaving skills and knowledge in India. I wanted to learn about innovative education and development projects that involved handweavers. Beginning in New Delhi and continuing in Ahmedabad at the National Institute of Design, I talked with many people who were knowledgeable about the complex problems faced by handweavers in India. Now, I was on my way to Phalodi to visit a weavers' organization that I heard was exemplary as a development initiative. The train arrived at Phalodi station and we hired an auto rickshaw to take us to the outskirts of town where Urmul Phalodi Weavers' Centre was located. We were greeted warmly at the entrance to a large stone-built complex and taken to a guest room on the second floor that opened onto a large balcony. Within a few moments of settling into our room, a student from the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) in Delhi came to tell us that a jeep was leaving shortly for one of the weavers' villages and we were welcome to come along. After a meal together, I climbed into the back of the jeep with the four students and we rode along a narrow highway, bouncing over potholes and raised sections of the road. Speaking loudly over the noise of the jeep, I learned that the students were doing a Craft Documentation Project, travelling from village to village in Rajasthan studying traditional handicrafts. Pitloom Weavers of Western Rajasthan After about twenty miles we turned off the main road onto a one lane paved road. Soon we were following a track across dry sandy soil, with the jeep kicking up dust until we stopped next to several mud houses with thatched roofs. We were taken to where a weaver worked. Hundreds of fine black warp threads stretched parallel a few inches above the ground, extending approximately fifteen feet from the weaver's sitting position in a thatched roof shelter. A young man, seated on a thin cushion on the ground, passed a shuttle of fine black cotton back and forth across the width of the warp. With his feet, the weaver operated treadles located in a small pit dug in the earth below the loom. The treadle action moved the loom harnesses which separate different groups of warp threads. With skilful fingers, the weaver quickly manipulated the yarn to make detailed design motifs in a black and white fabric. This weaver was one of twelve men from his village of Bengiti who had been trained at the Weavers' Centre and become members of UMBVS. Traditionally the weavers of this area wove plain cotton cloth for pattus (shawls) or woolen dhurries for floor coverings, working on traditional two foot wide pitlooms that are used extensively in India. During three months of training at Phalodi, they learned to weave new designs on looms of three, four or five foot width. They also learned about the aims of UMBVS. On completing their training, weavers could buy a new wider loom at half price and they were given yarns to start weaving designs on order. Although many of the weavers of Bengiti were away from the village working in the fields until evening, we were taken to see one other weaver. A woman in purdah, face covered with a bright yellow fabric, was sitting at a pitloom just outside the door of her house, weaving a two foot wide piece with no design details. She had learned to weave five months earlier when three women from the village took part in the first UMBVS weaving training program for women. Traditionally, men are weavers in most regions of India and women help by doing the tasks of winding yarn and making the warp. However, when women expressed interest to join UMBVS and learn to weave, a new training program was started. We returned to Phalodi as the sun was setting. Skeins of coloured yarn were spread out to dry all along the balcony railing of the Weavers' Centre. That evening, Ram Chandra Barupal, Chief Executive, and Revata Ram, manager of income generation programs, visited us. With one of the NIFT students translating, we learned that two people who worked for Urmul spoke English and they would be arriving the following day. The fact that none of the managers of UMBVS know English is considered a problem for the organization because English is the language for dealing with the outside world. The next morning, smells wafted up from juniper wood fires heating huge metal dye vats. We watched as two strong young men lifted a heavy metal rod holding about ten skeins of hot wet yarn that had been submerged in the vat. They carried the dripping weight over to a rack and then repeated these motions with three more rods full of dyed yarn. Then, wearing long rubber gloves, they washed each skein in soapy water, squeezing out the remaining water. Supervised by the dye manager, these men had learned the exacting process of yarn dyeing, and each month dyed approximately 120 kilograms of yarn needed by weavers to fill orders. In another room four men worked cutting woven cloth into sections for cushion covers, measuring and joining fronts to backs, and sewing finished edges. Across the hall, there was a storeroom with floor-to-ceiling shelves of colourful woven products, such as shawls, bedspreads, cushion covers and upholstery material. In this room, the stock manager receives new products from the villages and, after quality checking, ships the pieces to fill orders in metropolitan areas. The weavers' training area, a large room at the back of the building, was temporarily being used for making door and window frames for a new weavers' centre in Pokhran about sixty kilometres away. The Phalodi Weavers' Centre had become too small for the growing organization and a new much larger building was under construction. Urmul Marusthali Bunkar Vikas Samiti Formally registered in January 1991, UMBVS began with seventy weavers from six villages. In 1997, membership had grown to one hundred and fifty weavers from thirteen villages in three districts of West Rajasthan. Weaving is central to the organization and other activities include: a women's development program, an integrated rural development program, and the implementation of an extensive education program in conjunction with the Rajasthan Government. Since its inception, the vision of UMBVS has been: "To establish a society free of inequalities and oppression." The mission is "To organize the target group and help them to participate freely in all aspects of their development by making them more aware of their rights; to keep traditional craft alive by upgrading their skills." The goals are to free weavers from exploitation by traders and middlemen, provide alternative marketing support and regular remunerative employment, and to bring about social and economic development, including the preservation of art and culture in a professionally managed environment (UMBVS unpublished report, 1997). Before UMBVS began training weavers to make new designs and establishing markets to sell their products, weavers in many villages had stopped weaving. Some of them had been investing money in yarn, dyeing the yarn, weaving, and then taking their products to markets. Sometimes their work would sell, but often they lost their investment and had to take out loans from money lenders, which resulted in the loss of some of their belongings. Some weavers had arrangements with merchant-middlemen from big towns like Jodphur, Jaiselmer and Bikaner. The middlemen provided weavers with dyed yarn, but paid very low wages for the weaving while selling it at a good profit. Now, as members of UMBVS, weavers are paid at the end of each month by a production manager who picks up finished work and pays on a piece rate basis according to the size and detail of each design. UMBVS then sells their products to stores in major Indian cities and also for export. Over a ten year period, UMBVS has emerged as a vibrant, successful organization through the energy and commitment of key people brought together during desperate circumstances. Ram Chandra Barupal is one of the key figures. On my last day in Phalodi I had opportunity to tape record a translated interview with him, learning how his vision and effort in the face of many challenges are integral to the Urmul story.

RAM CHANDRA BARUPAL

Ram Chandra came from a village in Jaiselmer district where the stony, rough land was not conducive to farming. He attended school until ninth grade, and then left against the wishes of his parents because he saw that his family was poor and he needed to earn some money. He did physical labour, including work in the salt mines. Although his father did not weave, Ram Chandra used to sit at his great uncle's loom whenever the old man stopped weaving to go to eat. Sometimes Ram Chandra wove several inches, but got it wrong, or sometimes he broke a warp thread. Afraid he had spoiled the weaving, Ram Chandra ran away when his great uncle returned. But sometimes he got it right. At sixteen he decided to learn to weave. His family mocked him because they wanted him to go to school. So Ram Chandra worked alone to figure out how to make a warp. The first one took him seven days to make properly and then there were other difficulties with the loom set up. After twelve days of weaving he completed his first pattu which he sold in the market for 14 rupees. Out of that, ten rupees paid for the wool. Ram Chandra persisted even though no one supported what he was doing. Weaving appealed to him and he appreciated the historical and cultural aspect, knowing his ancestors had also been weavers. He thought weaving was a better way to earn money than doing tough physical work. Gradually he earned ten to fifteen rupees for his pattus above the cost of the wool. He began to weave for villagers who wanted his pattus while other weavers were selling outside the village. Later he began buying wool in bulk and having other weavers make pattus which he sold at fairs and outside markets. Nobody in his village knew how to do the traditional embroidery weave. So Ram Chandra bought a woven pattu from a fair and over six months he perfected the technique of inlaid weft. Gradually he became known for his unique pattus. People could look at them and know that he had woven them. Since he was able to weave fast and his quality was very good, he began to earn up to thirty rupees for a pattu while others earned ten to twelve rupees. When his family was in debt, Ram Chandra stopped weaving for two years to earn more money. He took out a loan to buy seed to sell. He sold food at hotels and at fairs. He bought sheep and goats, reared them, and took them to sell in big markets in Delhi. He invested in a fodder machine and made fodder for cattle. But he didn't make a profit from any of this work. When the Government of India sponsored a famine relief effort in the nearby Bikaner district in 1987, Ram Chandra went to work there on a watershed management project, building a small dam. Whenever he earned some money he returned to his village and his loom to weave.THE URMUL TRUST

The Urmul Trust, an autonomous organization based in Lunkaransar in the Bikaner district, began work in the field of primary health care and non-formal education in 1986. A year later, Rajasthan experienced its worst drought of the century and people faced near starvation. Under the leadership of Sanjay Ghose, the Urmul Trust started an experiment in income generation based on dormant wool-related crafts of the region. Local women knew how to spin and the raw materials and equipment were available locally. Urmul Trust arranged to sell all the yarn that the women produced to a Government Khadi agency in the area. While six hundred women were employed in thirty villages around Lunkaransar, the Urmul Trust accumulated fifteen hundred kilograms of spun wool. However, the Khadi agency refused to buy the yarn because it was not produced by a certified body within their jurisdiction. Sanjay Ghose and others at Urmul Trust began looking for alternative places to sell the spun wool. An itinerant salesman told them that the pattus he was selling had been made by the weaver, Surjan Ram, of the village Bhojasar. They went to meet Surjan Ram who was working with about ten weavers who filled orders for Jodhpur merchant-middlemen. After some discussion, a decision was made for Urmul Trust to supply wool to the weavers and then purchase everything they made on a piece rate basis. Dastkar, an NGO based in Delhi, helped Urmul Trust by arranging exhibitions and selling the woven products at city bazaars. Sanjay Ghose and Tarun Salwar (who joined Urmul Trust after completing studies at London School of Economics) saw the potential for a good income generation project in the weaving of pattus using the two traditional embroidery styles of the region, Bhojasari and Mhulani. They needed weavers who were able to do this, but only a few in Bhojasar knew the embroidery style. Surjan Ram suggested they go to the annual fair near Pokhran to meet weavers selling woven products. At the fair, Surjan Ram put Sanjay Ghose and Tarun Salwar in contact with two master weavers, who introduced them to another weaver who knew the Mhulani embroidery style. This weaver told them about Ram Chandra, who wove the Bhojasari embroidery style. In this way, a network began among the weavers who later became the managers of UMBVS. Several people from Urmul Trust went to meet Ram Chandra. Impressed by his work, they asked him to weave for them and Ram Chandra started right away. Others from Urmul Trust and two designers from National Institute of Design (NID) made trips to watch him weave. They asked him to come and work for them in Lunkaransar, offering him a stipend of 450 rupees per month to learn new designs and train other weavers. At the time, Ram Chandra was earning more than 800 rupees by sitting at his loom. So he told them, "I'll learn here. I've learned myself. Give me a new design and I'll figure it out myself." He refused to go to Lunkaransar but they persisted and came back two or three times. When he did go, Urmul Trust again asked him to train local weavers in Lunkaransar. He said, "No." There were weavers he knew in his village that he wanted to train first. After teaching them for one year to weave and do the embroidery styles, then he would be ready to train other weavers. Urmul Trust agreed to his condition of training weavers in his own village first.FORMING THE WEAVER'S SOCIETY

Five weavers from the Phalodi district went to live in Lunkaransar and Urmul Trust laid the foundation for their knowledge about creating and running an organization. The weavers learned the basics of marketing, accounting and yarn dyeing. They learned to weave new embroidery style designs and products designed by a student from NID. Surjan Ram began working as middleman for Urmul Trust, taking wool to weavers in the villages and bringing finished products back to Lunkaransar. In the first year, they trained fifty local weavers. Few weavers in the villages were clearly informed about the Urmul Trust. They thought it was a rich international organization and they wanted to earn as much money as possible. The weavers produced in quantity, but their quality suffered and Urmul Trust accumulated a large amount of poorly made unsold products. Urmul Trust called a meeting of weavers and 150 attended. Sanjay Ghose explained Urmul's objectives to the weavers, saying, "You are poor people who have been taken advantage of. We want to organize you into a group that one day will stand on it's own" (Barupal interview, 1997). Product-related marketing problems had to be faced. Pattu weaving was traditionally done in wool, but the market for new woollen products such as cushion covers was seasonal. And people living in the cities of South India did not want wool furnishings because even the winter months are not cold. With product and marketing advice from Dastkar, the decision was made to weave with cotton in order to reach a broader market and provide a steady income to weavers throughout the year. There were also problems with the yarn dyeing being done in the villages. Because the colours bled, the popularity of products diminished and sales stagnated. After Ram Chandra and several others were trained at Lunkaransar in the use of new chemical dyes, the quality of yarn colours improved. Products started to do better in the market but there was still trouble with quality and with sending products on time. Some sections of Urmul Trust complained about the high costs of covering the weavers' annual losses. They said they could no longer accept poor quality work. Sanjay Ghose and Tarun Salwar went from village to village to talk with weavers, explaining that Urmul Trust was a large institution with health and education programs and it was not imperative for them to support the weavers. They decided to shut down the weaving production for two months to emphasize the need to increase the quality of finished work, stop taking things for granted, and begin to stand on their own feet without depending on Urmul Trust. Only the very good weavers and the trainers continued weaving during that time. In 1989, a meeting was called at Phalodi to discuss the formation of a weavers' organization separate from the Urmul Trust. Subsequently, meetings were held in the villages to encourage weavers to become active in strengthening the organization. To instill a sense of ownership for the society, each weaver was asked to contribute 1000 rupees as capital; profits and losses would be shared by each member. According to Sanjay Ghose, UMBVS "was borne out of a sense of desperation. They had to do something to get work otherwise they would have been reduced to absolute penury" (Ghose, 1992). UMBVS was registered formally and an elected executive committee was comprised of the five weavers who had been working at Lunkaransar. These leaders went back to Lunkaransar to learn more about running an organization. Each according to their interests, they learned about stocks, accounting, and marketing.. The UMBVS leaders wanted to leave Lunkaransar and set up their organization in Phalodi, a central location for the weaving villages of Jodhpur, Jaiselmer and Bikaner districts. Sanjay Ghose and Tarun Salwar were keen for the weavers to go on their own, but others at Urmul Trust did not support the idea. Instead of waiting and possibly not having any support for the idea later, the UMBVS leaders decided to leave for Phalodi. It turned out that half the weavers wanted to work in Phalodi and the other half wanted to stay in Lunkaransar. Some weavers mistrusted the leaders. They believed the leaders would exploit them, earn all the money, and do nothing for them. To settle the dispute, a compromise was reached and Urmul Trust sent four people to Phalodi to work there, including a manager, a designer, and an accountant. After a while the UMBVS leaders realized that the managerial staff sent from Urmul Trust had high expenses on marketing trips. The Urmul staff stayed in hotels that suited their higher social background. When costs were totalled the leaders realized how much profit was needed just to cover these expenses. They decided to manage without the staff from Urmul. However, some weavers opposed this idea, continuing to mistrust the leaders and believing that the presence of the Urmul Trust staff members ensured fairness. Despite the resistance of some weavers in the villages, the leaders persisted. They wanted the freedom to run the organization themselves. They knew they were being blamed losses that were due to a management problem. So they sent the staff from Urmul Trust back to Lunkaransar. Then the leaders were very strict about their own expenditures because they wanted to prove UMBVS could make a profit. They lived spartenly; they took buses, never taxis, and they slept in inexpensive tariff hostels where sleeping was outside. By the end of the first year in Phalodi, UMBVS made a profit. After covering the Urmul Trust losses of the previous year, the organization was able to distribute a bonus to the weavers. Receiving a bonus for the first time, the weavers finally believed in UMBVS and saw that the leaders could manage the organization on their own. Living and working in a rented house in Phalodi, the weaver-managers were discriminated against because of caste. UMBVS needed their own building, especially for the training of weavers. A weavers' meeting was called and the weavers decided to contribute to the purchase of land. UMBVS also applied for and received international funding from Action Aid and Save the Children's Fund. In 1994, the construction of Urmul Phalodi Weavers' Centre was completed and UMBVS began to train more weavers.In the Village of Karwa

After a morning exploring the Urmul Weaver's Centre, David and I were greeted by Kunjan Singh, returning from Bikaner. Kunjan had been hired by UMBVS as a designer after completing her studies at the National Institute for Fashion Technology eighteen months earlier. For her NIFT diploma project she had documented the handwoven textiles produced by Urmul weavers and she had created a design collection of home furnishings and apparel for production by UMBVS. Kunjan invited us to go with several of the UMBVS managers to a meeting in the village of Karwa, sixty kilometres or about an hour and a half jeep ride away. After lunch, we travelled narrow roads through dry land, occasionally passing clusters of houses, or women walking with large bundles of sticks for firewood on their heads. At times we passed camels pulling a load of wood or a large metal storage tank for water. These sights were continually new for me. The spaciousness of the desert and clean air was a blessing in comparison to the crowded polluted cities of Delhi and Ahmedabad. During the ride, Kunjan explained that a semi-annual meeting was held in each village to discuss whatever issues or problems of weaving production had occurred in the preceding six months. The UMBVS managers also share information about new designs, markets, and initiatives. Kunjan said the scope of UMBVS continues to expand and people from more villages want to become members of the society. Before a new village joins UMBVS, a detailed study is undertaken of the village, the people, the agriculture, economy, incomes, and resources. However, the managers do not want the organization to become too big and they train only five new weavers a year. Arriving in Karwa about four o'clock, we went directly to an area adjacent to the weaving manager's pitloom, where a long warp stretched out from the thatched roof shelter. The weaving manager and two elders greeted us. An Indian cot was put out and David and I were told to sit there. Everyone else sat on a carpet on the ground. We were served tea and Kunjan translated some of what was being talked about. We learned that the meeting would be delayed until weavers working in the fields returned at the end of the day. Kunjan suggested we walk around. There were several connected buildings belonging to two brothers and their families. A hard packed earth courtyard between a circular mud house and a rectangular stone house had been swept meticulously. We were introduced to the weaving manager's wife who greeted us from behind her veil and spoke to us intently in Hindi. Children stood nearby looking at us curiously. Walking further, I was attracted by a long blue warp stretching out from another weaving site. We were welcomed to go inside to look at the loom. When David asked about an object he saw hanging from the roof beams, the weaver took down a five stringed instrument, unwrapped its cloth cover and began playing. Within minutes a dozen young men appeared, some with small drums or hand cymbals, and together they played and sang. Kunjan explained later that they were singing a devotional song to Lord Ganesh who protects their weaving. It was a song about a weaver preparing his warp and being ready to weave. While the men and boys were singing, I noticed the peg positioned a short distance from the warp beam on the right hand side of loom. The peg is tied with a rope that holds the warp in tension. Called the Viniak, another name for Lord Ganesh, this peg is the most sacred part of the loom. Each time a weaver starts to weave, he prays to the Viniak or touches it as a form of respect. During festivals he puts jaggery (ground sugar that is considered auspicious) on the Viniak as an offering of food (Singh interview, 1997). Dusk arrived by the time we returned to the meeting place and were told that the meeting would not occur until late that evening. Ram Chandra said this was a good time for me to put questions to the weavers. Five Karwa weavers sat with two elders and my four companions from UrmulPhalodi. I was pleased to be given this unexpected opportunity. I asked: What is different now that you are weaving for Urmul? One young man said that now he has much more respect from people in the village. He used to take construction work to earn money, but now weaving lets him earn money and feel respected at the same time. An elder expressed the satisfaction of being respected for their work, in contrast to the sense of desperation that forced them to take anything in pay. There used to be competition; if someone asked 10 rupees for a piece another would undercut him by saying his weaving was only 8 rupees. Now there is a fixed price for each piece which everyone knows. "We are a community now," he said. It was dark when we ate dinner prepared by the weaving managers' wife. Then David, the weaving training master, and I were driven back to Phalodi, leaving the others to stay in the village of Karwa for a late night meeting. The next day we joined them at a different village for another of the semi-annual meetings.Changes and Challenges for Weavers

Weavers are traditionally lower caste people who have been oppressed for a very long time. According to Ram Chandra Bharupal, the most important achievement of UMBVS has been to help weavers break out of the constraints of the caste system. As they became united and formed a strong identity, they were able to fight back. Over time, there has been a significant psychological change, a feeling of relief and self-respect. Ram Chandra said, "You don't have to drink water separately or pour it from a vessel untouched. It is a change to your psyche that you are not looked down upon so much anymore. It is no longer only the higher castes that are worthy. Weavers can say, "We are useful too. We too can sit on the chair. We can wear good clothes." In addition, weavers' social and economic status in the villages has improved. Because of their success in earning a decent living through weaving, weavers are viewed differently by other villagers. Their voices are heard more often. Earlier, weavers worked for the well-off higher caste people. They took loans from them, and were indebted to them. Under UMBVS a new kind of prosperity has freed them from confinement of caste and low status. Very few weavers are in debt, but if needed they can take out a loan from the society. Women also can have savings and get loans. In order to initiate a women's development program, the men who were weavers agreed to put thirty percent of their monthly pay directly into the wives' accounts. UMBVS managers are prepared to meet more challenges. Ram Chandra said, "It is a changing, dynamic process. When something demands that you learn, you set about learning it." Recently they tackled the legalities and paperwork for government permission to receive international funds directly rather than indirectly through other organizations. The next challenge is to learn about forming a company and getting an export license to be able to bypass the middlemen in international sales. Marketing continues to present major challenges. Although UMBVS has established reliable contacts they still need to assess and expand their markets. To fill export orders they have to maintain a high standard of quality because products with small flaws are sent back. They have to be very specialized and meet deadlines, and at the same time, take into account that weavers are farming during the four months of agricultural season. UMBVS works through consultation with the weavers, who feel in turn it is their wishes being carried out, their organization being run. However, the UMBVS leaders are continually trying to involve more weavers in the community development process. Some weavers are initially concerned about their own welfare, but discussions at annual meetings, awareness camps and exposure visits teach them to see others' point of view. Summary Reflection An enormous commitment of time and energy is required in the operation of UMBVS to bring the benefits of the organization to as many people in the villages as possible. Given the hardships that arise from extreme climatic conditions, rigid social system, and poor access to health and education programs, an organization that helps villagers break the constraints of poverty is highly regarded. UMBVS builds on the skills and knowledge of weavers as a base for economic and community development, and in the process, contributes to the preservation of local culture, specifically, a unique form of handweaving. The Urmul Trust played an important role in bringing together the best weavers of the region for an initial income generation project, then giving the weavers access to knowledge and information that eventually allowed them to manage UMBVS on their own. Input from experts on product and design development and marketing was also essential in moving toward the weavers' economic survival. The vision and determination of Ram Chandra Barupal, along with the other weaver- managers, has been instrumental in the formation and ongoing development of the organization. The UMBVS managers have taken on immense challenges, keeping the needs of the village weavers continually in mind. Initially, competition made building trust and developing a sense of shared ownership a struggle. Weavers and their families are learning to overcome attitudes that have restricted them in the past; they are learning new ways of working and living in their communities. By being participants in the opportunities offered to them through UMBVS they are creating a conducive climate for preserving handweaving and achieving new freedoms. References Barupal, Ram Chandra. Interview by C. Jongeward, translation by Ardash, tape recording. November, 16, 1997. Phalodi, Rajasthan. Ghose, S. 1992. The Urmul Experiment. In Report of the National Meet of the Crafts Council of India. New Delhi. Satyanand, K. and Singh, S. 1995. India's Artisans: A Status Report. Society for Rural, Urban and Tribal Initiatives (SRUTI): New Delhi. Singh, Kunjan. Interview by C. Jongeward, tape recording. November, 8, 1997. Phalodi, Rajasthan. Urmul Marusthali Bunkar Vikas Samiti. 1997. Unpublished report, photocopy. Phalodi, India. This article was published in 1998 in Convergence,31(4), a publication of the International Council for Adult Education The author acknowledges the financial assistance of the Government of India through the India Studies Programme of the Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute.| The Project: WEAVING PEACE Design Student: SMITHA MURTHY, SRISHTI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY Location: BONGAIGAON, ASSAM Duration: 6 MONTHS - MAY 2002 TO NOV. 2002 Sponsor: THE ACTION NORTH EAST TRUST (ANT) | |

|

Background About the Community The BODOs, a tribal community in Assam, have been involved in a political struggle against the Assamese for the last two decades. The ethnic conflict has been exacerbated by the erosion of farming land of the tribal community by the main rivers, thus creating a struggle for resources between different communities. Many landless families survive on the men's daily wages and the sale of vegetables by the women in the local haats, both not being reliable or steady sources of income. Reaching the markets takes much time and energy, as the women have to walk many miles. Almost all BODO women can weave as the craft is passed on from generation to generation. As weaving is a household activity, every home has a throw and fly shuttle loom. Traditionally the women wove textiles for themselves and their families in their spare time. Using acrylic yarn, that was easily available, the woven items were the dokhna and chaddar, an unstitched traditional garment, around 50 inches wide and 3 meters, long that is draped from the chest to the ankle and is tied above the chest and at the waist. |

| Almost all BODO women can weave as the craft is passed on from generation to generation. As weaving is a household activity, every home has a throw and fly shuttle loom. Traditionally the women wove textiles for themselves and their families in their spare time. Using acrylic yarn, that was easily available, the woven items were the dokhna and chaddar, an unstitched traditional garment, around 50 inches wide and 3 meters, long that is draped from the chest to the ankle and is tied above the chest and at the waist. | |

| The Mission Women weavers, especially the landless, needed a market to transform their weaving activity into a significant source of steady income. This required a market that appreciated hand woven products; product diversification and adaptation of the colours and designs to suit customer preferences - a risk that individual landless weavers were unable to take.It was hoped that through this project, the women who otherwise supported their family income by selling vegetables, would now get a constant source of income. |  |

Objectives

The project was called 'weaving peace'.

|

|

|

PHASE 1 An attempt was first made to spread the idea to all the villages involved. Textiles woven by weavers of other states were shown to the stake holders. This actually boosted their interest in the project. The idea of urban people wearing and using textiles woven by them fascinated them the most. |

| Simultaneously the designer started a thorough research into the variety of traditional motifs, colours, raw material, the origin and stories behind the creation of each motif. With this knowledge the acceptability of traditional motifs and colours for a probable market was identified and studied. Documenting traditional motifs and designs of the BODOSs to create a reference point for future development became an ongoing process throughout the project. A number of villagers and people with different issues relating to the BODOs were spoken to for feedback and information. | |

| PHASE 2 The designer studied and learnt the weaving technique practiced so that developments could be demonstrated on the loom rather than conveyed verbally or through drawings. While she was there at the behest of ANT, the designer had to gain the trust of the weavers and establish her own equation with them. In her own words, she was completely paralyzed due to the language barrier. |  |

|

The process started with Smitha, the designer, communicating first with the men of the community, establishing her credentials and gaining the confidence of the women. What helped was the fact that she was from Bangalore, where many of their own children were studying. She ate and drank whatever they offered, keen not to give offence to anyone. Seeing Smitha's daily struggle of commuting 30 kms on a bicycle to reach their communities, weaving herself, making the prototypes - and all this without knowing their language - won the respect of the weavers. |

| PHASE 3 After studying the old, heirloom dokhnas and chaddars, four main motifs that the weavers were familiar with were chosen which were mixed and matched to create new designs. The colour pallet was retained for its close identity with the community. Each of the five traditional colours ranging from lemon yellow, orange to deep red had its own significance and its own local name.The borders used were traditional - on both striped and plain cloth. Experimentation was carried out with uneven borders and different pattern were created using the same warp. |  |

| PHASE 4 Sampling Stage - 4 months The beginning was made with five weavers in one village using cotton yarn, which itself was difficult, as the cotton yarn broke and faded more easily when compared to acrylic or synthetic yarn they had gotten used to. Slowly the cloth was woven. The women were paid for their time and effort - an amount much higher than that paid to other Assamese weavers. | |

|

PHASE 5 The initial products developed were unstitched textiles like shawls, stoles and scarves which helped the weavers adapt to further developments and initiated them into commercial weaving for a distant market. The warps were planned in a way they could be turned into skirts and garments similar to those worn by Manipuri women, a culture they were familiar with.The next stage was the production of garments: Prototypes of the stitched and completed products were made and included jackets and skirts. This excited the women who admired and tried out each garment. Production of ready make garments was a different matter altogether and it was imperative to find somebody close by. Eventually they located a boutique in Guwahati, in Assam that could stitch the garments. |

| PHASE 6 The textiles and products were exhibited and sold at 'Nature Bazaar', an exhibition organized by Dastkar in New Delhi November 2003. The products received a very good response from a distant urban market. | |

| In Retrospect Smitha Murthy, Designer, Weaving Peace Project December 2004 | |

| Today when I look back to the journey from the five weavers we started sampling with to the 130 weavers we support today I feel one big achievement has been that women now see weaving as a constant source of income and not just a leisure activity. There has been constant appreciation for the designs and textiles from consumers and I see great potential ahead. The weavers are now registered under a different name- 'aagor', and have formed a managing committee of their own. I would however call this project truly successful when I see the women running this weaving program successfully on their own. I hope the day is not too far when people identify the BODOs as creators of classic textiles with vibrant colours and intricate weaves and not just as people fighting for their right and land. | |

|

Through analysis, observation and discussion we need to reach an understanding, and if possible consensus, on what can be done to improve the marketability of the crafts and the status of crafts persons in the eight North-Eastern states and provide them opportunities and options. During my few visits – not too many in number but spanning over a period of twenty five years, some impressions have stayed. |

|

|

On my first visit to Sikkim I was fascinated by their weaves, though I was left with the impression of the prices being too high. When I did the costing, I realized that the weaver, for almost eight hours of non-stop work on the back strap loom was earning a pitiful Rs.10 only. She was not even getting 30% of the cost as 60% was going towards raw-material with 10% on incidentals. It should actually have been the other way round. |

|

|

|

|

Two years ago, I visited a village in Nagaland where there were two National Awardees in basket making. The price of the basket quoted to me was Rs.3000/-. It was artistic, authentic and extremely well finished. The problem was how many can he sell at that price. |

|

|

Going into details, I was told that the master basket maker himself goes to the forest to select the bamboo, cuts it, dries it, keeps it on top of a special open oven to destroy the fungus and then dries it for several days before it is ready to be cut into fine splits. It takes two weeks to process the bamboo. He uses only one implement the dao. One wonders why a group of people do not get together to do the various mundane jobs and leave the master to just weave the basket. One also wonders why tools made especially for the various processes are not accepted by the craftsmen. One also wonders why the various Bamboo Missions cannot make splits and why they cannot encourage basket weavers to use them where they are being made. |

|

|

|

|

There are many such stories but I would like to start with a statement that whatever one makes, the final test is the market place. If it sells, it’s a success because it brings money to the maker. As one goes around the fifty stalls at the Uttara Poorav Utsav North-East craft festival in Dilli Haat (28 Jan-8 Feb, 2009) one realizes that there are two distinct characteristics of the displayed merchandise – the revival of traditional designs – like in Assam and the attempt at contemporizing the existing items without deviating from traditional skills. |

|

|

I would like to take up here the case of the second category which can find a market for the bulk of consumers – creation of contemporary life style items inspired by and with the use of traditional skills. This includes garments, cushion covers, mats, basket trays and file folders, jewellery, wooden bowls and cutlery among others. |

|

|

|

|

We are therefore trying to focus on items that can compete in the market – have a good finish and an aesthetic design. They have to be a good quality, have a utility value and yet be able to fetch a price that makes them worth the while for a craftsperson. The market has three important components, design, quality and price – each enhances the other. The fact that sales are not good enough to provide continuous year round orders, points towards the problems. |

|

|

Difficulty in procurement of raw material specially yarn which is particularly unique to the North East. By and large, weavers buy yarn from the ‘Marwari’ and beads from the ‘Bhutia’. Cost is reduced by using acrylic and synthetic yarns. The weaver is not concerned where the yarn comes from. At the North-East Festival a start has been made by setting up stalls of yarn providers and the subsequent interaction on quality and price has led to the opening of new avenues. |

|

Price is a very important factor in finding a market. In an effort to reduce prices, the quality of raw-material is being compromised and the wages of weavers being reduced which eventually is reflected in the quality and finish going down. Situation on the ground points towards non-contextualized assistance, indifferent Govt. schemes, badly conceptualized with no follow up and monitoring of implementation, middlemen exploitation at acquisition of raw material level, poor design assistance, not cognizant of changing market dynamics. |

|

|

|

|

|

Schemes well intended but jobs half done, require just one little step forward to make them more efficient. Here are some suggestions: Hundreds of design schemes every year have not created even a stir, leave alone a revolution because they are not linked to the market. |

|

|