JOURNAL ARCHIVE

The crafts activist’s response to the designer’s note today says communities with age-old creative traditions deserve much more than ‘crude shortcuts’

An outfit from the Sabyasachi x H&M collab, Wanderlust

Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s response to the joint letter by a collective of Indian craft organisations, voicing concerns about his digitally-printed Sanganeri and Kalamkari lookalike collection for global brand H&M, had lots of words — basically saying that by putting Indian textile traditions in a mass production medium he hoped it would then generate a demand for the authentic artisanal product. Well, here’s hoping!

Laila Tyabji

The trouble with global clothing chains is that their existence depends on creating new trends on a seasonal basis in order to maintain a constant demand for their products. What’s ‘in’ today is not ‘in’ next season. Old stock is junked. That’s why it is known as fast fashion. Seeing a new range promoted by H&M in malls and high streets across the world creates avid demand at first, but then comes the saturation. Will customers really clamour for genuine handblocked Indian prints once they’ve bought the H&M versions, or will they simply move on to the next latest thing?

Nurturing artisinal luxury

I too have an H&M story. About 18 years ago, Action India, an NGO that works with deprived women in Delhi and its environs, approached Dastkar for help. H&M, under fire for sourcing cut-price merchandise from Asian sweatshops, had funded a project with women in Hapur, Uttar Pradesh, to train them to make beaded wristbands, then greatly in demand at their stores. The brand committed to placing orders once the women had mastered the skill. The accessories department at New Delhi’s National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) was commissioned to do the training and develop designs. However, when the project ended, the Swedish company decided that there was no longer a demand for the bands.

A quick recap

An outfit from the Sabyasachi x H&M collab, Wanderlust

Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s response to the joint letter by a collective of Indian craft organisations, voicing concerns about his digitally-printed Sanganeri and Kalamkari lookalike collection for global brand H&M, had lots of words — basically saying that by putting Indian textile traditions in a mass production medium he hoped it would then generate a demand for the authentic artisanal product. Well, here’s hoping!

Laila Tyabji

The trouble with global clothing chains is that their existence depends on creating new trends on a seasonal basis in order to maintain a constant demand for their products. What’s ‘in’ today is not ‘in’ next season. Old stock is junked. That’s why it is known as fast fashion. Seeing a new range promoted by H&M in malls and high streets across the world creates avid demand at first, but then comes the saturation. Will customers really clamour for genuine handblocked Indian prints once they’ve bought the H&M versions, or will they simply move on to the next latest thing?

Nurturing artisinal luxury

I too have an H&M story. About 18 years ago, Action India, an NGO that works with deprived women in Delhi and its environs, approached Dastkar for help. H&M, under fire for sourcing cut-price merchandise from Asian sweatshops, had funded a project with women in Hapur, Uttar Pradesh, to train them to make beaded wristbands, then greatly in demand at their stores. The brand committed to placing orders once the women had mastered the skill. The accessories department at New Delhi’s National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) was commissioned to do the training and develop designs. However, when the project ended, the Swedish company decided that there was no longer a demand for the bands.

A quick recap

- The recent Sabyasachi x H&M collection, Wanderlust, is flying off the shelves. But away from ringing cash registers, debates are raging about mass-produced designs and artisans not getting their due. The open letter to the designer highlighted the crux of it. ‘Many of the publicity statements speak of this collection as linked to Indian design and craft, while carefully omitting the fact that it has not been manufactured by any artisan’, it stated, adding that while Wanderlust talked about being traditional, nothing in it was handmade. In his response, however, Sabyasachi shared that the line was not meant as a substitute for the artisanal; it was meant to reach more people. ‘The H&M collaboration was part of a different mission, a mission to put Indian design on the international map… Just as ‘Make in India’ needs to be encouraged, so should ‘Designed in India’.’

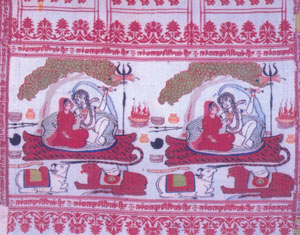

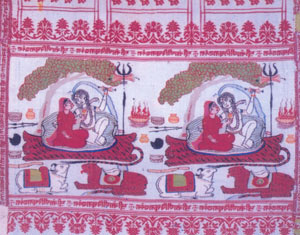

Sanjhi- the hand-cutting of paper for ritualistic and ceremonial rangolis - is commonly understood in its contemporary form as a ritualistic craft used in temples, and sometimes homes, for the worship of Lord Krishna. It is believed to have originated, according to the thesis forwarded by Asimakrishna Dasa, in his book "Evening Blossoms: The Temple Tradition of Sanjhi in Vrindavana", as 'a ritual worship undertaken by unmarried girls all over northern India to obtain a suitable husband'. Thus, while the temple craft is practised only by male priests and their male apprentices, the folk aspect of the craft was, and is, practised chiefly by unmarried girls. This craft, which involves the cutting of an intricate stencil depicting scenes from the life of Lord Krishna and the use of this paper stencil in creating a rangoli or floor decoration, became a temple tradition (according to Dasa) in the 17th century, 'when the devotional bhakti movement linked it to games played by Radha and the Hindu god, Krishna. While the ritual of sanjhi, in its devotional and decorative aspects, continues in villages and homes in north India, the temple tradition seems to have become confined to three important temples at Vrindavana and a single temple at Barsana, Radha's village. It is important to remember that all sanjhis, whether a part of the folk tradition or of the temple tradition, are made to be worshipped. According to Dasa: "At the time of worship they are transformed from works of art fashioned by human beings into a divine being, Goddess Sanjhi... the transformation from design to goddess comes about naturally with the offering of food bhoga followed by ritual worship aarti performed with burning wick and an offering of water.'" This explains the fact that effacing each sanjhi the next day and painstakingly beginning to create another one is seen not as tedium but a labour of love, 'to please Lord Krsna'. Presently the art of using the sanjhi is practised mainly in the temples and homes in Vrindavana in Uttar Pradesh and it is used to depict the different episodes in Lord Krishna's life; these episodes are linked to festivals in the Vraja calendar. The most important of these festivals is the vraja yatra, a period of 45 days in September and October when pilgrims from all over India visit the sites associated with the life of Lord Krishna. During this period sanjhis are used to decorate specific locations and places along the parikrama. The episodes in Lord Krishna's life that are depicted through sanjhis change every day, with appropriate themes adorning specific locations. For instance, at Govardhan the traditional sanjhi is one that will depict Lord Krishna lifting the mountain with his finger. At Barsana, the sanjhi depicts Lord Krishna playing Holi with Radha and the gopis. When the sanjhi is unveiled in time for the evening prayers it is worshipped to the accompaniment of songs narrating stories about Lord Krishna's life. The sanjhi is effaced in the morning and a new characterisation is then made. At the end of the pitr-paksha, a fortnight when Hindus perform rites for and offer prayers to deceased ancestors - when sanjhis are ceremonial - the materials used are then disposed off in the river Yamuna.

Underpinning the tradition in which unmarried girls create sanjhis is a legend that states that after due penance, the mind-born daughter of Brahma (the Creator in the Hindu trinity of Brahma-Vishnu-Mahesh, or the Creator-Preserver-Destroyer respectively) was granted three boons. She asked that her commitment to a single husband would remain unbroken and also that all those who worshipped her would have their wishes fulfilled. Transformed into the daughter of Agni (Hindu god of fire), she was taken up by the sun in whose orb she took the form of the threefold Sandhya. Sandhya represents not only the three junctures - dawn, noon, and dusk - but also the rituals to be performed at those times by men of the three upper castes (the twice-born).

Some link 'sanjhi' with 'samdhya'/ 'sandhya', which stands for 'evening' in Sanskrit and with 'sanjha', which is 'evening' in Brajabhasha (the language of Braja) and Hindi, thus linking the ritual with the time of worship, when the rangoli is traditionally unveiled to the sound of chanting in the temples.

Underpinning the tradition in which unmarried girls create sanjhis is a legend that states that after due penance, the mind-born daughter of Brahma (the Creator in the Hindu trinity of Brahma-Vishnu-Mahesh, or the Creator-Preserver-Destroyer respectively) was granted three boons. She asked that her commitment to a single husband would remain unbroken and also that all those who worshipped her would have their wishes fulfilled. Transformed into the daughter of Agni (Hindu god of fire), she was taken up by the sun in whose orb she took the form of the threefold Sandhya. Sandhya represents not only the three junctures - dawn, noon, and dusk - but also the rituals to be performed at those times by men of the three upper castes (the twice-born).

Some link 'sanjhi' with 'samdhya'/ 'sandhya', which stands for 'evening' in Sanskrit and with 'sanjha', which is 'evening' in Brajabhasha (the language of Braja) and Hindi, thus linking the ritual with the time of worship, when the rangoli is traditionally unveiled to the sound of chanting in the temples.

Hindu religion and scriptures have inspired human beings to live a spiritual life. These scriptures were predominately composed in Sanskrit with the Vedas being the oldest Sanskrit literature. The hymns or mantras, Sanskrit phrases, sacred symbols, Hindu Gods and historical epics of Hindu religion have always enlightened human minds. Since historical times, these hymns were recited on every occasion, be it joyous or sad. These sacred symbols were used to energize the universe with positivity. Now days, these hymns and sacred symbols are incorporated into the modern attire. The motifs inspired from historical epics and ethnic drapes of sari and dhoti are very much in fashion in present times. Sanskrit was part of our lives centuries back and even today in some or the other way, it is connected with us.

Costumes of early times

The term costume can be referred to as a dress in general or a particular class or period with distinguishing characteristics. Costume is one of the most visible signs of civilization. It provides the visual evidence of the life style of the wearers. Each community had different costumes. It was the community that used to decide what to wear, how to wear, the distinctions to be made in the costumes on the basis of sex and age, class and castes, religion and region, occasion and occupation. There used to be a community sanction as to which part of the body was covered or what was to be left bare, how to conceal and how to reveal. National costumes or regional costumes expressed the local identity and emphasized uniqueness.

In early times, the attire of Indian men included unstitched garments like the dhoti, the scarf or the uttariya and the turban. On the other hand, women used to wear the dhoti or the sari as the lower garment in combination with the Stanapatta (the breast band). The whole ensemble was of unstitched garments.

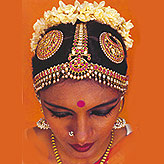

The bindi and its symbolism

Bindi, sindoor, tikka, pottu are the synonyms of the holy dot that was worn on the forehead. It was either a small dot or a big large round, sometimes shaped like a long straight vertical line, sometimes in a miniature alpana with a fine-tipped stick in triangles and circles to work out a complicated artistic design.

The word bindi is derived from the Sanskrit word ‘bindu’ or ‘drop’. It signifies the third eye of a person. It is a symbol of auspiciousness, good fortune and festivity. In older days, a small circular disc or a hollow coin was used to make a perfect round on the forehead. The conservative woman still uses kumkum or sindoor for making a bindi.

The jewel on the nose

Traditional Indian women always wore a nose-ring. In India the outside of the left nostril is the preferred for piercing as this is supposed to make childbirth easier. This is because Ayurvedic medicine associates this location with the female reproductive organs. In the old days, the bride’s nose was pierced and the auspicious nose-ring was worn during the pooja or prayer of Goddess Parvati.

The story of the sari

The origin of sari is obscure. But, Indian sari is the oldest existing draped garment as it has been mentioned in Vedas (the oldest existing manuscript since 3000 BC). Sari can be called a versatile cloth because it could be worn as shorts, trousers, flowing gown-like or skirt-like.

The word sari is derived from the Sanskrit words ‘Sati’ and ‘Chira’ meaning ‘a wearable length of cloth’. It is a long length of cloth measuring from 4 to 8 meters tied loosely, folded and pleated. It could be turned up into a working dress or a party-wear dress with manual skills. A woman’s ethnicity, class or caste background and the social norms influenced her choice of fabrics, colors and pattern. For instance, in North India a widow was expected to wear white, the color of mourning while red was considered the color of joy and marital bliss worn by the brides. These differences are noticeable even today especially in rural areas and traditional tribesWoman usually tucked the sari till the ankles, while the women who had to work in water or fields could tuck the front pleats between the legs to the back and tie the upper portion round the waist for free movement of hands and legs. At the same time it was as safe a dress as trousers. A nine yard sari was embellished with embroidery and gold designing. A gold, silver or cloth belt was fastened which kept pallu/ the end piece, pleats and folds in position. Rani Lakshmi Bai fought enemy troops on horse back wearing sari in the form of trousers and fastening the pallu with the silver or cloth belt. Tight tucking of the front pleats in the back was called Veeragacche (soldier’s tuck).

Varieties of saris

The sari is divided into 3 areas-

The story of the sari

The origin of sari is obscure. But, Indian sari is the oldest existing draped garment as it has been mentioned in Vedas (the oldest existing manuscript since 3000 BC). Sari can be called a versatile cloth because it could be worn as shorts, trousers, flowing gown-like or skirt-like.

The word sari is derived from the Sanskrit words ‘Sati’ and ‘Chira’ meaning ‘a wearable length of cloth’. It is a long length of cloth measuring from 4 to 8 meters tied loosely, folded and pleated. It could be turned up into a working dress or a party-wear dress with manual skills. A woman’s ethnicity, class or caste background and the social norms influenced her choice of fabrics, colors and pattern. For instance, in North India a widow was expected to wear white, the color of mourning while red was considered the color of joy and marital bliss worn by the brides. These differences are noticeable even today especially in rural areas and traditional tribesWoman usually tucked the sari till the ankles, while the women who had to work in water or fields could tuck the front pleats between the legs to the back and tie the upper portion round the waist for free movement of hands and legs. At the same time it was as safe a dress as trousers. A nine yard sari was embellished with embroidery and gold designing. A gold, silver or cloth belt was fastened which kept pallu/ the end piece, pleats and folds in position. Rani Lakshmi Bai fought enemy troops on horse back wearing sari in the form of trousers and fastening the pallu with the silver or cloth belt. Tight tucking of the front pleats in the back was called Veeragacche (soldier’s tuck).

Varieties of saris

The sari is divided into 3 areas-

Attire across genders and castes

Dhoti was the male counter part of sari. Men used to wear colorful dhotis with brocaded borders in a number of styles.

Attire across genders and castes

Dhoti was the male counter part of sari. Men used to wear colorful dhotis with brocaded borders in a number of styles.

Sari or dhoti has always been the most flexible dress for both men and women. Being an un-sewn cloth length, it could be worn parted and tucked breech-like for horse-riding, for swimming and other sports, it can be tightly worn and for martial sports and battle it can be draped in a short length. It gives an elegant appearance to men when the embroidered and fully pleated saris with big borders swayed as they walked majestically towards the durbar hall (royal senates).

Sari or dhoti has always been the most flexible dress for both men and women. Being an un-sewn cloth length, it could be worn parted and tucked breech-like for horse-riding, for swimming and other sports, it can be tightly worn and for martial sports and battle it can be draped in a short length. It gives an elegant appearance to men when the embroidered and fully pleated saris with big borders swayed as they walked majestically towards the durbar hall (royal senates).

Commoners wore saris without undergarments. A few of them could cover upper parts of their bodies with another piece of cloth.

Commoners wore saris without undergarments. A few of them could cover upper parts of their bodies with another piece of cloth.

Ancient brassieres

Majority of female figures in ancient Indian scriptures are devoid of a blouse, but there are some evidences depicting Indian women wearing brassieres. The first evidence of brassieres in India is found during the rule of king Harshavardhana (1st century) in Kashmir. Sewn brassieres and blouses were also worn during the Vijayanagara Empire.

Ancient brassieres

Majority of female figures in ancient Indian scriptures are devoid of a blouse, but there are some evidences depicting Indian women wearing brassieres. The first evidence of brassieres in India is found during the rule of king Harshavardhana (1st century) in Kashmir. Sewn brassieres and blouses were also worn during the Vijayanagara Empire.

Impact of ancient Indian scriptures on modern attire

“The language of Sanskrit is of a wonderful structure, more perfect than Greek, more copious than Latin and more exquisitely refined than either.”

- Sir William Jones

Sanskrit had once been an official language of India. Various measures have been taken to uplift the position of Sanskrit by Government as well as private bodies. For instance, the National Anthem of India is 90% Sanskrit, Sri and Srimati are the official forms of addressing an individual, the motto of Lok Sabha is Dharma chakra (“The Wheel of Law”), the All India Radio has adopted as its guiding principle and motto the Sanskrit expression Bahujana-hitaya bahujana-sukhaya (“For the good of the many and for the happiness of the many”), The Life Insurance Corporation’s motto is Yogaksemam vahamy aham, which is a quotation from the Bhagavad Gita, meaning “I take responsibility for access and security”, the great principle of India’s foreign policy is expressed by the Sanskrit term ‘Panca Sila’( means five principles).

Now-a-days, Sanskrit hymns and scripts are seen printed on costumes and painted on body.

Impact of ancient Indian scriptures on modern attire

“The language of Sanskrit is of a wonderful structure, more perfect than Greek, more copious than Latin and more exquisitely refined than either.”

- Sir William Jones

Sanskrit had once been an official language of India. Various measures have been taken to uplift the position of Sanskrit by Government as well as private bodies. For instance, the National Anthem of India is 90% Sanskrit, Sri and Srimati are the official forms of addressing an individual, the motto of Lok Sabha is Dharma chakra (“The Wheel of Law”), the All India Radio has adopted as its guiding principle and motto the Sanskrit expression Bahujana-hitaya bahujana-sukhaya (“For the good of the many and for the happiness of the many”), The Life Insurance Corporation’s motto is Yogaksemam vahamy aham, which is a quotation from the Bhagavad Gita, meaning “I take responsibility for access and security”, the great principle of India’s foreign policy is expressed by the Sanskrit term ‘Panca Sila’( means five principles).

Now-a-days, Sanskrit hymns and scripts are seen printed on costumes and painted on body.

Bhartiya scriptures include the Vedas, the Upvedas, and the Vedangas, the Smritis, the Darsh, the Shastras, the Upnishads, the Puranas, the Mahabharat, the Ramayan, the Gita, the Bhagwadgita and the writings of the jagadgurus, acharyas and saints. All this scriptures are composed in Sanskrit- the language of religion and culture. These scriptures talk about energy, universe and creation. Spiritual and intellectual efforts of hundreds and millions of people over millennia have graced India with a rich and complex culture. In present era also, those spiritual efforts are inspiring human beings to live a spiritual life. Their preachings have also inspired the designers to incorporate the holy Sanskrit ‘shlokas’ and sacred symbols into the modern attire.

Bhartiya scriptures include the Vedas, the Upvedas, and the Vedangas, the Smritis, the Darsh, the Shastras, the Upnishads, the Puranas, the Mahabharat, the Ramayan, the Gita, the Bhagwadgita and the writings of the jagadgurus, acharyas and saints. All this scriptures are composed in Sanskrit- the language of religion and culture. These scriptures talk about energy, universe and creation. Spiritual and intellectual efforts of hundreds and millions of people over millennia have graced India with a rich and complex culture. In present era also, those spiritual efforts are inspiring human beings to live a spiritual life. Their preachings have also inspired the designers to incorporate the holy Sanskrit ‘shlokas’ and sacred symbols into the modern attire.

Visualizing increases awareness and memorizing. The historical epics of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, murals of Hindu Gods, sacred symbols like Swastika and Aum have become an eminent part of fashion and are creating awareness and spreading message of spirituality across the globe. These are painted not only on fabric but also on body in the form of tattoos. Huge canopies, wall panels, carpets, prayer mats, dress materials and jewelry are designed using the ethnic mantras or symbols.

Tattooing and body painting is common amongst youth and these sacred symbols and hindu deities are the preferred tattoos by youth.

Visualizing increases awareness and memorizing. The historical epics of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, murals of Hindu Gods, sacred symbols like Swastika and Aum have become an eminent part of fashion and are creating awareness and spreading message of spirituality across the globe. These are painted not only on fabric but also on body in the form of tattoos. Huge canopies, wall panels, carpets, prayer mats, dress materials and jewelry are designed using the ethnic mantras or symbols.

Tattooing and body painting is common amongst youth and these sacred symbols and hindu deities are the preferred tattoos by youth.

The word swastika in Sanskrit means "well-being." This symbol has been an ancient and noble symbol of cosmic order and stability. In the Vedas, India's most ancient scriptures, the swastika is called "the sun's wheel" and is associated with astrological ritual and flourishing cosmic periods. In modern times, swastika is painted on t-shirts, kurtis, body and used in making jewellery.

The word swastika in Sanskrit means "well-being." This symbol has been an ancient and noble symbol of cosmic order and stability. In the Vedas, India's most ancient scriptures, the swastika is called "the sun's wheel" and is associated with astrological ritual and flourishing cosmic periods. In modern times, swastika is painted on t-shirts, kurtis, body and used in making jewellery.

Interesting pendants are designed taking these sacred symbols as an inspiration. Pendants and rings with inscriptions of Lord Ganesha, swastika designs, Lord Shiva and Krishna, Aum, Sanskrit words and phrases.

Interesting pendants are designed taking these sacred symbols as an inspiration. Pendants and rings with inscriptions of Lord Ganesha, swastika designs, Lord Shiva and Krishna, Aum, Sanskrit words and phrases.

Sanskrit is slowly coming up and it must be respected and regarded across the globe. This language is a repository of valuable knowledge of ancient Indian heritage. Though it’s use in day to day life has reduced but it has always been a part of our lives centuries back and even today in some or the other way, it is connected to us.

Bibliography:

Sanskrit is slowly coming up and it must be respected and regarded across the globe. This language is a repository of valuable knowledge of ancient Indian heritage. Though it’s use in day to day life has reduced but it has always been a part of our lives centuries back and even today in some or the other way, it is connected to us.

Bibliography:

|

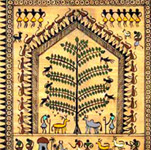

Folk paintings are pictorial expressions of village painters which are marked by the subjects chosen from epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata, Hindu `Purana`s as well as daily village life, birds and animals and natural objects like sun, moon, plants and trees. The color used extend from a vast range of vivid vibrant colors to subdued low hues, mainly derived from the natural material, while papers, cloth, leaves, earthen pots, stone and mud walls are used as canvas. Folk paintings are so variable from region to region dependant on various factors including the availability of material in different area. In arid Rajasthan the colors in the folk painting are vibrant and lustrous, painters in colorful Bengal seem to search for relief in sober subdued tones. Artists in Orissa pick out palm leaves for painting. While the women of north India found the whitewashed walls a setting for their colorful paintings, while Oriya artists choose red-clayed wall for white and black paintings. Saura (also spelled as Saora) are one of the tribal communities of Orissa. The Saora painting is a traditional folk art of the “Saura” tribe of Orissa. They are adept in art, painting and craft. Their well known Saora paintings are fascinating among the people of India. Saora paintings are done to please the Gods and the ancestors. These drawings are also made for averting disease, promoting fertility, festive occasions, in honor of their deceased and for ceremonial functions. Often, the artist painting on the village walls are directed by dreams and moments of enlightenment. Some of the characteristic features of these paintings include that the Saoras like many other tribes of India have a custom of making drawings on the walls of their homes. Motifs include horses, riders, monkeys climbing or perched on trees, deer, peacock, dancing villagers, elephants, lizards, tigers, goats, monkeys, sun, moon, huts, cattle, women with baskets, flowers, birds, combs, villagers playing musical instruments like trumpets, drums, gongs, ‘Idital’ the tribal deity, religious folklore, priests, worshippers. Sometimes they also depict dream sequences, seed sowing ceremony, harvesting, and hunting. They show a strong bond between nature and man by their paintings. Saora painting is painted with figurative pattern and figures are drawn in a stylized manner. A sense of energy and rhythm is seen in Saora painting. Figures are seen holding each other hands and dancing, beating the drums, hunting, riding on the horse, doing their daily chores. All natural scenes are depicted in a very unconventional manner. The central theme of most Saora, Ittal is a house which is represented by a circle. Figures are placed in the panels like circle, triangular around the Ittal. The composition of Saora paintings are filled with beautiful representation of flora, fauna and animal life. They express their philosophy that religion is about worshiping, respecting and protecting the nature. Process: Traditionally, the Saora painting, which are called ‘ittal” are made by anyone who is good in drawing and the artist need not be a priest, but if he becomes adept is known as an ‘Ittalmaran” or picture man. Saora believe they often do see the pattern of their ittals in their dreams. The artist needs excellent skills to make these paintings since the work on these paintings is fairly elaborate. For wall paintings, a brush is made from a bamboo split, while black colour is collected from soot generated out of lamps, sun-dried rice is crushed to from white powder, and all these are mixed in water, and juice from roots and herbs to make a paste. The colour that is finally obtained is black and white. In recent times, artists have also started painting on paper, and on 'American' card boards, and use acrylic colors to paint. Motifs are stylized and drawn in a particular manner. Different geometrical shapes are used to draw the motifs like for human figure, two opposed triangles which meet tip to tip is drawn first, then add arms, legs and head. They follow the similar technique for the rest motifs. This Saora printing resembles Warli painting of Maharastra. But it is more intricate and colorful than Warli. Saora paintings have now become the source of livelihood for many Saora families. Traditionally painted on walls, these painting are today painted on ply wood, canvas, cotton cloth, and paper and tusser fabric. Today, the artists are exploring different mediums and formats to make Saora painting more appealing.

Reference:

http/www.janganman.net/indian-culture-indian-folk-painting.html

http/www.potliarts.com/shop/

http/www.rareindianart.com/index.php?main_page=page&id=34

http/www.indianetzone.com

http/www.rangeenkagaz.com

http/www.potliarts.com/shop/

http/india4you.com/srcm-saura_painting.php

http/www.rareindianart.com/index.php?main_page=page&id=34

Reference:

http/www.janganman.net/indian-culture-indian-folk-painting.html

http/www.potliarts.com/shop/

http/www.rareindianart.com/index.php?main_page=page&id=34

http/www.indianetzone.com

http/www.rangeenkagaz.com

http/www.potliarts.com/shop/

http/india4you.com/srcm-saura_painting.php

http/www.rareindianart.com/index.php?main_page=page&id=34

`Sati’ `satika' (in Sanskrit), 'sari’ `scree' ‘dhoti’ `luga' (in Hindi), are the words used for the traditional female garment of India, although women in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka also wear the sari. This long drape is simple to wear by just wrapping and folding, which can be done in many ways. Various wearing styles often provide the regional identity of the wearer. The length and width of sari varies to region and quality of yarn' This rich, vibrant world of sari was produced by using various raw materials such as muslin, cotton, silk, cotton with zari, silk with zari etc. These were woven in different techniques like plain weave, jamdani, ikat, zari brocade, tapestry etc. Sometimes these were embellished through embroidery, printing or painting. The vast range of motif and design, from human to animal figurine and from bird to floral pattern, enriches its grace and elegance. All these aspects make 'the sari' an exclusive and exquisite attire among all other garments of Indian women. The anatomy of a traditional sari comprises of `field', 'anchal' or 'end panel' and 'side borders'. The fields of sari remain either plain or all over patterned with buta/butis (big/small size flower motif) or stripes or checker and many more designs. The anchal or pallu are usually woven with heavy patterning such as those seen in the Baluchari sari of Murshidabad (Bengal) or zari brocade from Varanasi, (Uttar Pradesh) or Kanchivaram (Tamil Nadu) or tapestry weaving from Paithan (Maharashtra) etc. Sometimes these pallus are decorated with simple stripes like the Cant saris of Bengal or the tribal saris of Madhya Pradesh. Beautiful fringes or tassels were often added to end pallu, which adds charm to the garment. Borders, warp-wise, on both sides of field are the usual style in most saris and provide a good fall to sari when worn. The pattern of side borders usually corresponds to the design of the field, of late patterning in similar design all over the sari has become popular, and this doesn't provide any place for the end panel or border. The term 'sari' or`saree' has originated from the Sanskrit word ‘shati' and ‘shatika'. However, its evolution has ancient roots, which may be found in Rig Veda which refers to this garment as 'neevi' or ‘nivi’. Sanskrit literature often mentions 'adho-vastra', which refers to lower garment. 'Uttriya' and 'kanculi, breast band, were other garments for women.3 The popular story book of 4th-5th CE titled, Panchatantra' records the word sari. A reference to the sari occurs in Sabha Parv of the epic Mahabharata, where Daupadi's chirharan episode has been mentioned. It narrates that Daupadi's sari was extended by Lord Krishna, when Dushashna tries to pull it off in the court of Dhritrastra (Kaurva king of Hastinapur). The epic Ramayana also mentions the word shati. The shati refers to adho-vastra in both the epics, which are dated around 4th century BCE to 4th century CE. Buddhist (Vinaya Pitaka) and Jain (Kalpasutra) texts also provide a great deal of information on women's garment. Other important references are obtained from various travelers' accounts, where social, religious and cultural life of a particular period and region gets mentioned and many times sari and its wearing styles are narrated. An important description of sari and its wearing style is recorded in an early 15th century CE Portuguese traveler's account.' The Hindi ritikalin literature which dates back to 18th-19th century provides plenty of references to the sari, its colour, texture and quality.

Apart from literary references, sculptural evidences (stone, terracotta and bronze) also throw light on the evolution of sari, which is very interesting and fascinating. The earliest example of drape is evident from stone image of a bearded priest, which belongs to Harappan Civilization, (c.3500-1500 BCE). The Priest is draped with shawl or cloak, which comes in front under the right arm, covers the upper body, goes to left shoulder and finally falls at the back. To some extent such draping style is followed in the sari as well. The stone images of yaksha-yakshi illustrate antariya or dhoti, which belongs to 3rd-2nd century BCE. Apart from stone images, the illustration of wearing sari is depicted in many terracotta sculptures from Sunga period, which dates back to 2nd century BCE.

[caption id="attachment_179544" align="alignright" width="183"] 1. Lady dressed in antariya or dhoti and patka or sash stands on vase. Antariya is draped around legs, which is popularly known as 'langha' style. One end of the sash is tied an antariya and goes around both shoulders and falls in front. Gandhara, 2nd century CE, stone size- 20.2 x 10.4 x 4.7cm; Acc no: 59.533/3 10.4[/caption]

1. Lady dressed in antariya or dhoti and patka or sash stands on vase. Antariya is draped around legs, which is popularly known as 'langha' style. One end of the sash is tied an antariya and goes around both shoulders and falls in front. Gandhara, 2nd century CE, stone size- 20.2 x 10.4 x 4.7cm; Acc no: 59.533/3 10.4[/caption]

A terracotta female figure, housed in the Ashmolean Museum (United Kingdom), is adorned with langavali dhoti' or `draped between the legs' and the pallu goes over the left shoulder. She is adorned with elaborate headdress and jewellery like yakshi images of early phase. Female figures of the Gandhara period (1st-2nd century CE), sculptures especially queen Maya, her escorts and Goddess Hariti, beautifully represent the attire of that period. (Plate 1) These sculptures show the long anatariya worn in `kachcha' or ‘langha' style, which covers the waist portion and one end, is continued over the left shoulder. The Gandhara sculptures are very important examples especially in the context of a sari like garment and its draping style. Many terracotta temples were made during the Gupta and post Gupta periods in Uttar Pradesh, Western Region and Kashmir. These temples were decorated with panels and tiles, which usually portrayed man's day to day activities besides other scenes. Panels of the brick temple of Bhitargaon (Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh) depict several examples of male and female costumes. Women, in one of the panels, stand in front of a male figure and hold a water vessel. She is adorned with a sari, while the man is in a long garment. Other panels, from the same site, illustrate procession scenes or amorous couples where women are in a sari while men are in loincloth. The Gupta period (c.300-550 CE) terracotta sculpture (in Brooklyn Museum, U.S.A.) depicts a lady wearing a full skirted sari draped around her entire body. This resembles the nivi style of sari wearing, where the sari is wrapped with a front set of pleats on the skirt, and the body wrapping up over the wearer's torso.

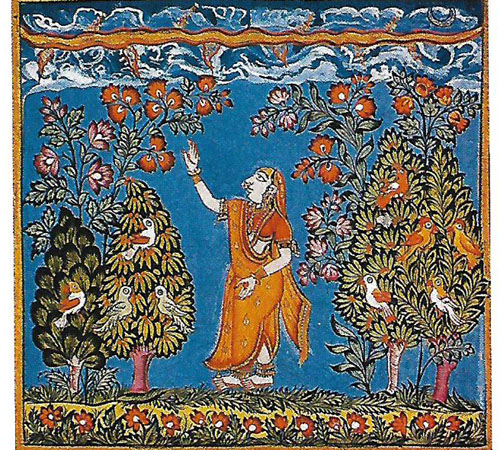

2. Folio from Rasmanjari manuscript depicts lady in garden. She wears lagvoli sari having pleated the lower portion, and draped the pallu on the front, covering her head and finally falling at the back. Early 18th century CE; Martha/Deccan style; size- 12 x 30 cm; Acc. no: 61.1185

Women use to drape the sari across the legs and tied up in the front is this style. This gives flexibility to women while carrying out the work in the agricultural field or sea or any other work. Several Maharashtrain, groups have migrated down to Karanataka and Andhra Pradesh from time to time, and they played an important role in the social and cultural life of locals. Interestingly, several women of Karanataka and Andhra Pradesh still have the similar wearing style of sari, as reflecting in number of miniature paintings of the region. (Plate 2) The brick temple of Harwan (Kashmir) of the post Gupta period (c. 5th-6th century CE) reflects the continuity of the Gandhara trend. One such terracotta tile depicts a woman dressed in a sari with pleats, which she has lifted from one side. She covers her head and shoulder, while both ends of the garment hang on either side. The length of sari is up to the ankle. (Plate 3) Another tile from same center depicts a woman carrying a pot. Her sari has a loose flared lower portion; pallu comes in the front, diagonally, and covers the left shoulder and head. The portion of end panel after the head covering falls at the back.

3. Tile depicting lady holding a pot in her left hand while see clutches a portion of the sari from her right hand. Its seems to ends of sash are hang on both sites. 5th-6th century, Harwan, Kashmir, Terroctta , size; 46 x 42.2 x 4.8cm; Acc.no. L.186

Some terracotta temples in Bengal were constructed in a later period, and these have also highlighted the garment tradition of that phase and region. Another important aspect is the folk tradition of painting and sculpture in the eastern, northern and southern region, where women are dressed in a sari besides other garment. Apart from paintings and sculptures, there are some references of sari in numismatics especially on Gupta period coins. A gold coin of Samudragupta (c.330-380 CE) illustrates the Goddess Lakshmi, who wears a loose flared sari like garment; especially the drape around the legs gives the feel of loosely worn sari. (Plate 4)

4. Coin depicting Goddess seated on a throne and adorned with loosely draped sari like attire 4th century CE,gold,size: Dia-2 cm; Acc.no: 51.50/2

In addition to sculptural art, there are several examples of paintings on walls, cloth, wood etc., which show females in different types of attire and sari is one of them. Cave no I of Ajanta mural (Western Maharashtra) shows a woman sitting with a man looking up at the courtly scene. She wears a short sari with narrow warp-wise borders and weft-wise stripes draped over her left shoulder. In another example an old woman looking around a door in a voluminous sari in the kachchha style is painted in the cave no VIII. Sometimes one gets the depiction of a stitched upper garment along with a lower garment, from cave paintings of Ajanta and Bagh (Madhya Pradesh). The illustration of a dancer in a long, full sleeved choli with an apron is one of the important examples found from Cave I of Ajanta. Her dancing pose gives the impression that her lower garment is flared and has flexibility. A number of surviving paintings, done on wood, cloth and paper, mainly from western India show women as Goddesses, musicians, dancers and maids busy in daily activities are dressed in a sari. Most of these examples illustrate two prominent styles; 'single piece or loosely draped sari and 'tight fitting around legs, with odhani or patka. The Jain Kalpa Sutra (15th century CE), paintings on paper, depict the female figures wearing dhoti-scarf covering her coiffure and a part wrapped round the waist and bodice. (Plate 5) This draping style of sari, as represented in Jain paintings, traveled in many parts and in south India, where it got illustrated in wall paintings. Depiction of Kalpsutra's style of sharp edges in pallu of sari one can see in the murals of Lepakshi temple. There are several other noteworthy mural paintings in south Indian temples, which illustrate social life and various textiles and costumes. The important ones are - Rajarajeswara temples of Tanjore (early 11th century A.D), Virabhadra temple at Lepakshi (mid-16th century), Virupaksha Temple, Vijaynagara (17th century), Ramalinga Vilasam Palace (Ramanathapuram) (18th century). Often these mural paintings show females are in saris and blouse or choli. These saris have pleats in front, it covers the waist and pallu falls in front from right shoulder, which comes from left shoulder. Women with full or half sleeve blouse are shown in the Virupaksha temple and Tiruvalur temple paintings.

5. Jain Kalpasutra folio show Goddess is surrounded by female attendants. All of themare adorned in sari, which has angular lower portion, while pallu or utteriya around shoulders and half sleeve blouse or choli of contrast colour. 15th century CE, Language prakrit; Script: Devanagri; Paper; Size: 12 x 30 cm; Acc. no: 48.29

Persian manuscripts and the Deccani school paintings of 16th -17th century CE also provide illustrations of the many interesting garments of men and women. The sari-choli; lengha-choli-odhani remain the popular woman garments as depicted in these paintings. The Tarif-i-Hussain Shahi, the earliest and one of greatest Deccani illustrated manuscripts from Ahmadnagar (1565-69 CE) illustrates women in sari and half sleeved choli. Ragini Patahmshika (1590-95 CE), from the Ragamala series, belongs to the Bijapur/ Ahmadnagar style of painting. This illustrates three women wearing a sari having pleats in front and an anchal, with pointed edges which covers the waist, then goes over the left shoulder and then on the right shoulder, finally falling on the front side. The pointed edges of the pallu and pleated attire were the characteristics of Jain Paintings. (Plate 6) Perhaps it is an attempt by the artists to show the natural movement of fabric. Later on, from the 19th century onwards the depiction of the sari became more popular in the miniature and folk paintings of Bengal, Orissa and the Southern region.With the passage of time sari also underwent many changes in raw material, design, composition and construction etc. This happened due to many reasons such as fashion, change of users' taste, re-invention, royal patronage etc. Around the mid-18th century weavers of the region of Maheshwar made special sari, which were inspired by the carving of temples and palaces of Alilyabai Holkar, queen of the Holkar state. These silk and cotton Maheshwari saris were woven with small butis, stripes and in soft soothing colours, which reflect royal elegance. The region of Paithan in Maharastra was patronized by royal ladies of Maratha and Peshva rulers and the Paithani sari industry flourished during their rule. This tradition traveled down south with them and royal ladies of Nizam of Hyderabad, (Andhra Pradesh) were also fond of Paithani sari. The charm of Paithani sari, shaloo (chaddar) etc. had attracted the contemporary painters also and the best examples are to be found in the paintings of Raja Ravi Verma. This artist has painted most of his female figures adorned with rich and vibrant Paithani/Madurai and other traditional saris'. There are references that designers from Paris or other places were also involved in designing saris for these royal princes and queens in the first quarter of 20th century. Two designer chiffon saris designed for the Princess of Hyderabad and Berar, are at present housed at the Fashion Institute of Technology and Louvre Museum, Paris. Changes took place, in each time phase, either in the drape style of the sari or some new garments were attached with it and each time the sari has enhanced beauty. With the sari kanchuli/ choli/ jumpher /blouse, as an upper garment, were added in different times and regions. Another important garment attached to sari is the petticoat, a lower garment. This long skirt is used for tucking in the pleats of sari.

6. Painting 'Ragini Patahmshika' show there females in sari-choli. The multiple pleats of sari are in the lower portion, then pallu covers the waist portion and go to head, finally falls either in the front or at back. Ahmandnagar/Bijapur, Deccan, c 1590-95 CE, Opaque watercolour and gold on paper, size: 26 x 20 cm, Acc.no. BKN 2066.

All these literary, epigraphic, numismatic arid sculptural references to a sari show the continuity of this garment, perhaps the oldest indigenous women attire. Initially during the Vedic period women were using anatariya' (lower garment), `uttariya' (upper garment) and 'kanculi' or kayaband' (waist band). From Sunga and Kushan period onwards slowly and gradually we do get the narration of garment like a sari and by the Gupta period draping style of sari became much clearer. Initially with the saris, choli or jampher and then the blouse was added. Later on, the petticoat (long skirt) was added and presently these two garments have become an integral part of the sari. Now internationally sari is known as Indian women's attire and it has traveled a long way. From all these years not only the sari's wearing style has developed, but also variety of manufacturing techniques, designs, new materials etc. All these gave a new dimension to saris in each period and region. Changes do happen but the charm and grace of sari remain the same. NOTES- Chishti. R.K. & Sanyal A., Madhya Pradesh Saris of India, (ed) Singh M, New Delhi, 1989, pp-25-46.

- http://sanskritdocuments.org/dict/dictall.html

- Rai. L., Hindi Ritikavya Ke Adhar par Parchalit Vastron ki Adhayan in The Research Bulletin (Arts), Punjab University, Chandigarh, No. LIV, (V],1966. p-1.

- Panchatantra, I, 144.; Sulochana Ayyar, Costumes and Ornaments as depicted in the Sculptures of Gwalior Museum, Delhi, 1987, p-36

- Rajagopalachari C, Mahabharata, Bombay, 1975, pp-94-95.

- Ramayan, 5-19-3.

- Chandra. M., Costumes and Textiles of Sultanate period, in Journal of India Textile History. Vol. 6 (1961) pp. 5-6.

- Rai, ibid, pp-1-8.

- The breaded Priest is in Karchi museum, Pakistan.

- L. Linda, The Sari: Styles- Patterns- History- Techniques-London, 1995, p-10.

- Linda, ibid, pp-10-11.

- Singh, R.C., Bhitargaon brick temple, in Bulletin of Museums and Archaeology in UP., Number 8., Dec. 1971, p-32, pl-1.

- Singh, [bid, p-33, p1-2.

- Linda, ibid, p-11

- http://dakinidesigns.net/1000petals/BlueAvatar/ bharatanatyam/Resources/Margarets_sari_paper.pdf, p-8

- Housed in Metropolitan museum, acc.no. 1994.77.

- Dasgupta. P., Temple Terracotta of Bengal, New Delhi, 1971

- Jam. J., National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum, New Delhi, Ahmedabad, 1989, pp-123-129

- Vanaja R., Coins & Epigraphs in Master pieces of National Museum Collection, (ed) S.P.Gupta, New Delhi, 1985, p-140, p1-177; p-141, p1-180.

- Ghosh. A, Narita Murals, New Delhi,1987, pl-)000/1

- Linda, bid, p-10.

- Seth. M, Indian Painting: Tile Great Mural Tradition, USA, 2006, ibid, p-59.

- 13th-15th centuries manuscript cover in wood are painted, which are preserved in Jain Bhandhara and other libraries. The Jain cloth and paper painting tradition specimens found in museums.

- http://www.jaindharmonline.comiliteralanjnIt.htm

- Sivaramamurti, C., South Indian Paintings, New Delhi, p-118, p1-72.

- Sivaramamurti, ibid, p-105; p1-59; pp-123-125; p1-77-79.

- Manuscripts like; Tarif-i-Hussain Shahi, Pem-nem and paintings housed in City Palace, Jaipur, (Rajasthan) National Museum, National Gallery of Modem Art (New Delhi),

- Melnemey. T., in Sultans of Deccan India, 15---1700 (ed) Haidar N and Sardar M., USA, 2015, pp-56-57.

- Mathur, V.K., in Nauras the Many Arts of the Deccan, (ed) Bahadur. P. R., and Singh K., New Delhi, 2015, p-106.

- Skelton. R., Arts of Bengal,(Exhibition catalogue), London, 1979 pl- xii.; Seth, ibid.

- Dhamija J., Pathan' Weavers: An Ancient Tapestry art; in Marg; The Woven Silks of India, (ed) Dhamija, J., Mumbai, 1995, p-80

- Kapur, G. Ravi Varma's Unframed Allegory, in Raja Ravi Verma, New Delhi, 1993; pp-96-103.

- In some mural paintings of south India it has been observed that women were wearing sari without upper garment. However earlier references mentions that kanchiki (kind of breast covering) was the garment used to cover the breast portion besides choli was also used by some women. The present form blouse became popular in the last century.

- Bhandari V. Costume, Textiles and Jewllery of India, Tradition in Rajasthan, Delhi, 2004, pp-8-9.

- Author is thankful to Dr. R.K. Tewari (Dy. Curator), Dr. S.V. Tripathi (Curator), Shri Tej Pal Singh (Dy. Curator) and Dr. V.K. Mathur (Curator) for providing the images of coin, manuscript, archeology and miniature painting respectively and Shri Rakesh (photographer) for the images.

The eighteenth-nineteenth centuries witnessed the exquisite embroidery work on cotton or silk textiles, costumes and furnishings made for domestic and export markets. These beautiful needle works were created by using floss silk thread embroidered with variety of stitches and the prominent one was 'satin stitch', the focus is on this stitch here. The satin stitch embroidery, around this period, was practiced in Gujarat, Delhi, Agra and Deccan region, but the way it was carried out in the Western Himalayan region is un-parallel in beauty and grace. The 'Western Himalayan states' or 'Punjab Hill states' provides such a variety that we see the picturesque and folk style coverlets (popularly known as Chamba rumal) with religious subjects from Hill region and geometrical floral pattern decorated coverlets were more close to plains. The tradition of embroidering costumes, furnishing and miscellaneous things were also prevalent in the hill regions. Each of the broad categories have many sub-groups, on the basis of embroidery technique, design, pattern and the base fabric, while use of floss silk threads and satin stitch remain common. The intricately embroidered coverlet and hanging stands out among all varieties of Himalayan region needle work and had attracted art lovers, visitors to the region and textile historians. Many travelers, scholars had contributed about the aesthetic beauty of these coverlets, its various styles etc. Scholars had tried to identify the different production centers with the help of old museums specimens and had compared it with Pahari miniature paintings. However, there is no unanimous opinion regarding the origin and practice of satin stitch in the region, which is mostly considered to be 'Chinese or Persian or Turkish or perhaps Indigenous'. If outside influence is there, then from where and how it has reached to Himalayan states, what was the route; who were the people practicing it and if its indigenous then how long the satin stitch has been practiced in the region and which were the centers. These are some of the unsolved questions. An attempt has been made here, to understand the use of satin stitch, its variations, its application on variety of objects of 'Western Himalayan Region' besides other centers, how it has travelled to the region and the possible connections. This will be discussed taking into consideration of available specimens preserved in museums, private collections and written records. Satin Stitch Stitches used in Pandri embroideries has been referred as 'double satin stitch' by some scholars', while some put it in darn stitch category.2 George Watt, a renowned scholar, whose noticeable contribution on Industrial Art of India was in between 1884-19033.He describes the technical difference between satin and darn stitch very clearly: - "In the satin stitch, the needle catches a hold of the sides or outlines of the structures to be ornamented and returns backwards and forwards until the required covering has been effected. Occasionally it goes round and round so that the work is double, that is to say, it is the same on both sides. So also it is not infrequent for satin stitch to be padded or cushioned by patchwork or by thick threads first sewn over the portions that are to be subsequently elaborately embroidered." "In darn stitch the needle runs along nipping up small portions of the textile at intervals" Another detail description of both the stitches we get from Reader's digest, which mention:- "Darning stitch is basically several rows of running stitches used for filling it, consists of long floats of stitches with few fabric threads. It has variations like basic darning which is single sided and stitches are aligned in brick arrangement. Double darning is double sided where one row of stitches is worked in first journey and then spaces are filled with stitches in return journey. Work is carried in structured rows." "Satin stitches are used for filling with a smooth surface. It has variations like basic satin, long and short, encroaching and brick" The close examinations of Indian variations of satin stitches have several styles, which create not only the soothing effect, but also the different variations. Such variations are possible by modifying the basic stitches, resulted effect and impact differently. Dr. Rohini Arora has done in-depth study on variety of satin stitches and its uses in pahari embroideries, this will be discussed in details in her paper. Satin Stitch Embroidery Tradition of India The surface ornamentation on textiles and costumes through needle work has a long history in India. Excavation findings of bone and metal needles from Harappan sites6indicate the early existence of some form of stitching. Although a few early pieces are available from 15th-16thcenturies onwards, but literary references of ancient and medieval period texts mention that the trappings were embroidered with threads, metallic thread and even the gems. However, in the absence of any technical details we are not sure about the nature of embroidery practiced in early days. Kashmir, Agra, Delhi, Banaras, Sind, Baluchistan and Kathiabad, Quetta, Bombay, Bengal, Azamganj, besides Chamba, Kangra and Kullu of Himalayan states were the centers, where satin stitch embroideries were practiced. This is mentioned in the catalogue of "Indian Art exhibition", which was held at Delhi in 1903. Author of catalogue G. Watt mentions that rumals (Handkerchiefs) made as table cover were made in Kashmir. The silk was used and stitches are mostly chain and satin.8Delhi and Agra cities of Mughal period had the advantage of rich populace and patronage. Many forms of needle work were practiced here and satin stitch embroidery is one of them. Artisans with adoptability and sensibility created things like curtains, screen cloths, table centers etc. These things were embroidered with silk or metal threads with satin stitch on the silk or velvet as base fabric, as per the requirements of European. In Baluchistan also 'satin stitch' and 'double satin stitch' embroidery was practiced, besides other varieties. This was practiced on cotton or linen handkerchief and on the table cloth. Among the peasant community of Kathiawar region of Gujarat chakla (square coverlet), caps, toranas, (door hanging) were embroidered with beautiful floral patterns often done with satin stitches. In Delhi exhibition, in 1903, a beautiful tea table cloth was exhibited, which was embroidered with colour silk in double satin stitch was recorded from Quetta. Another example of this exhibition in the loan collection was six kamarband (waist band). These satin stitch embroidered beautiful kamarband show tiny floral buffs, with colourful silk threads are like delicate painting. All these got attention of art lovers, got recorded in the exhibition catalogue. Prior to Delhi exhibition catalogues, the technical details are not available. This official catalogue is very significant, as it provides the detail description of art work, their products, production centers, manufacturing process, master price winning master artists etc. We are not aware of whereabouts' of specimens reported in Delhi exhibition; however the early published examples show the religious themes. One of the earliest embroidered specimen work in satin stitch, known so far, in Calico Museum, Ahmedabad (Gujarat), is a narrow Jain band or panel which depicts eight Vidyadevi (Goddesses of learning) This 15th-16th century red cotton panel is divided into nine compartments, which is surrounded by floral borders. A decorative disc is in center; while four divisions on either side show four-armed goddess gracefully seated under arched toranas. This religious panel has been worked in satin stitch and laid threads couched with contrasting colours. There are two more specimens of similar style of workmanship; one is in the Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum, Hyderabad and another is in the Musee National des Arts Asian Antiquities, Gumit. The uses of these narrow band is not very clear, perhaps these were given to Jain nuns on their invitation, or may be to wrap around manuscripts or hang behind the platform where Jain religious leaders held discussions. Around the same period there is reference of coverlet embroidered with satin stitch in Chola Sahib Gurudwara, Gurdaspur district, Punjab. It is believed that this rectangular coverlet is embroidered by Bibi Nanaki (1464-1518) to gift her brother Guru Nank Dev at the time of his marriage in 1487. Instead of religious theme, this white cotton coverlet shows several female and male busy in day to day activities of life; horse rider, man running with bird, female standing under the tree, deer etc. Embroidered with silk threads in maroon, green, pink, yellow etc gives the impression of early work of the region. Contrast to religious theme and figurative work, floral pattern dominates in the embroideries of Deccan region, which was also carried out with silk and metal threads in satin stitch. Several embroidered floor coverings, hangings, carpet's coverings made in Deccan are the prized possession of several museum and private collections. As per Japanese archival records, embroidered furnishings were exported around mid-18th century from Golconda of Deccani region to different parts of the world. These reached Japan through Dutch East India Company, on which a Japanese Scholar Dr. Yumika Kamada of Waseda University, Tokyo, had carried out an in-depth research. These hangings, carpets and floor spreads show floral pattern embroidered with floss silk and silver threads on cotton base fabric with satin stitch besides other stitches. These textiles illustrate medallion design and tree of life with peacocks, birds etc. The uses of such embroidered textiles differed from country to country. In Japan flowering tree type hanging reached in 1774, where these were used by the Taishi-Yama, one of the thirty-two floats, during the annual Kyoto Gion festival. Castle in the Netherlands attests that embroideries from Deccan were brought to decorate the castle's interior. These floral patterned furnishings were embroidered with bright silk colour, sometimes shaded also. 19th century cotton base mat embroidered with floral pattern with silk and metal thread are in Mehrangarh collection, Jodhpur and National Museum, New Delhi. Around same region and time, important specimens are found with white cotton costumes, parkas embroidered with silk metal threads with satin stitches, which dates back to late 18th to early 19th century. National Museum has a few white cotton patkas, which shows beautiful tiny floral motifs on end panel and narrow border on horizontal side (plate-3.1) besides a white cotton angrakha is also embroidered in same fashion. [caption id="attachment_188176" align="alignright" width="235"]

Pl. 3.1 : Patka (Sash) has plain field and pallu (end panel) depict tiny flower buti on pallu central or south India, late 186 to early 19th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and metal threads, satin stitch. Photo-Courtesy: National Museum, New Delhi.[/caption]

Pl. 3.1 : Patka (Sash) has plain field and pallu (end panel) depict tiny flower buti on pallu central or south India, late 186 to early 19th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and metal threads, satin stitch. Photo-Courtesy: National Museum, New Delhi.[/caption]

Often we find the book covers made of wood, palm with cloth covering to cover the sacred texts. Many times the Jain book covers, rectangular in shape, were made either painted or covered with cloth and in many cases these are embroidered with distinct patterns. Several 18th or early 19thcentury book covers have been found in Jain bhandars and in museum collections. The book covers, in Calico museum, are beautifully embroidered with silk or silver-silver gilded wires on velvet or silk base fabric. National Museum also has 19th century embroidered book cover, which depicts four-armed Goddess flanked by male and female winged attendant within rectangular frame in front; while back show flower composition and pair of peacock. Uses of satin stitch with colourful silk threads come out well on metal thread background. (Plate 3.2 &3.3) Another type of book covers are embroidered with floral pattern. The 19th century book covers of Calico Museum, show the fine embroidery work depict different type of floral plants like three poppy plants, flowering plants with leaves and flowers or peacock etc. Some of them depict shaded work of satin stitch in green, indigo colours, which are similar to furnishings and patkas from Gujarat or Deccan. Another example of shaded satin stitch embroidery is the girdle, carpet, canopy, part of borders which show flowering plants with leaves and flowers worked in green shaded with indigo. Among these 19th century examples, a small canopy is a beautiful example of satin stitch workmanship. Such silk canopy was hung over the seat of Jaflower buin monks, depicts floral medallion in the center with flower upon each outer cusp and corners illustrate quarter medallion and conventional cypress trees grow towards the central motif.

The costumes, furnishings and religious textiles were embroidered on velvet, silk or cotton fabric which were worked with satin stitches. The symbolic motifs, narrative figurative or tiny tis are the patterns appeared on

Pl. 3.2 : Manuscript cover show the four-armed goddess flanked by winged morchhal (peacock feather flying whisk) bearers on either side, western India, late 18th to early 19th century, cotton base has metal thread ground and embroidered with silk metal threads, satin stitch. Photo-Courtesy: National Museum, New Delhi.

Pl. 3.2 : Manuscript cover show the four-armed goddess flanked by winged morchhal (peacock feather flying whisk) bearers on either side, western India, late 18th to early 19th century, cotton base has metal thread ground and embroidered with silk metal threads, satin stitch. Photo-Courtesy: National Museum, New Delhi.

Pl. 3.3 : Reverse view of manuscript cover show pair of peacock and flower motifs Photo-Courtesy: National Museum, New Delhi.

Pl. 3.3 : Reverse view of manuscript cover show pair of peacock and flower motifs Photo-Courtesy: National Museum, New Delhi.

these artifacts. These were produced at different centers in north, west and southern region of India around late eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

Satin Stitch Embroideries from Western Himalayan States The 'Western Himalayan States' or 'Punjab Hill States' have rich tradition of satin stitch embroideries done on coverlet, hanging, costume, fan, cap, floor spread, chaupar spread, etc. Floral, geometric, secular and religious themes were creatively produced on these textiles. The square or circular coverlets were perhaps made more, which are in most of the Indian textile collections. These white/red coloured cotton/mulmal coverlets were embroidered with floss silk threads and sometimes with metal threads with various types of stitches and satin stitch remain the main. These stitch could be either single or double satin, which were worked in two distinct styles; folk and classical. The theme of Lord Krsna (Raslila, Krsna playing flutes, Krsna in garden, Krsna flying kites) were embroidered on these coverlets under the influence of Bhakti movement around 12th-13th centuries. Besides Krsna, aivite themes were also illustrated; the prominent ones are Holy Family, Gajantaka, Garigadhar Siva with Gangd or with Bhagirathi etc. Scenes from Ramayana, Ganega, Hanuman, Goddesses etc. are the other subjects often occurred on these coverlets. These coverlets have multiple uses, covering the offerings to God-Goddess and to offer to Goddess temple of the region. Apart from religious uses, these were also used as scarf tying on head known as thathu '. Sometimes Krsna or gopas in Kangra paintings are shown wearing such scarf. Many times Chhabri (basket) are also shown covered by circular pieces known as chhabu. Sometimes long rectangular hangings, to some extent created in classical style, were especially made to gift some important visitor to the region. As one such hanging has been gifted by Raja Gopal Singh to Lord Mayo, (Governor General of India) when latter visited the Chamba valley on 13th November 1871. This is in Victoria and Albert museum collection and depict Mahabharat battle scene. The war theme appears to be popular during the 18th century as two such long panels have also been reported, besides the first is in Calico Museum and another one is in National Museum. For the big size hanging another subject often appeared is the Nayak-Nayikabheda. This literary subject has been much painted in Pahari miniature paintings and 'Pahari embroideries' also. In the Hill States there were many tribes like Gaddi, Gujjar, Kinners, Lahila, Pangwala etc. Costumes of these people have influence of Punjab and Jammu region. Gaddi women wear chola and dora in their daily life. As Gujjar male use to wear a Kashmiri type of short and Punjabi type tamba, while women wear paijama, loose shirts and a long piece of cotton cloth to cover the shirt. People of these states like to wear colourful costumes and some of costumes were beautifully embroidered. Choli, kamarband, scarf and caps are the pieces, which are embroidered with intricate work." Rosary cover (gaumukhi, dice boards (chaupar spread) manuscript cover or wrap, fan are the other embroidered cloth. These are embroidered with floral, geometric patterns. Chamba Rumal or Pahari Coverlets: Nomenclature The usual notion is that the term `Chamba Rumal was coined by J.P. Vogel, who visited in 1903 in the region and got impressed by the fine quality of workmanship.34Around this period another catalogue was published titled, 'Indian Art at Delhi', which do not mention the term `Chamba rumal. Rather G. Watt, author of the catalogue mentions, those embroideries were practiced at Kangra and Kullu center besides Chamba. He further mentions that, “the shepherdesses (perhaps he refers to folk style) as also the ladies of the palaces have from time immemorial wiled way their leisure time in embroidering cotton handkerchiefs done by a form of double satin stitch”. This description informs that handkerchiefs were embroidered at other centers, besides Chamba, where these were embroidered with brilliant coloured flowers and animals or mythological human group.35 Prior to Delhi exhibition another exhibition was held at Glasgow in 1888 tiled, 'Glasgow International Exhibition' and T.N. Mukharji wrote the catalogue of this exhibition named as 'Art Manufactures of India'. Mukharji records, 'the embroidery known as Chamba Rumals are peculiar to Chamba and Kangra. He further talked about the embroidery wrought in the household of one of the Rallis (Queen) of Chamba is kept in the Indian Museum at South Kensington (now named as Victoria and Albert Museum, London), perhaps refer to famous Mahabharata Hanging. Yet another, state level exhibition was held in 1881 at Lahore titled 'Punjab Exhibition. The report of this exhibition mentions the practice of embroidering handkerchief in hills (of Punjab states). Apart from new products, old specimens were also exhibited as sample, which were loaned from different people and places. Report further mentions that Raja of Chamba lent collection of many things and the elaborate pictorial rumals were one of them, which were embroidered in silk and gold on both sides. These coverlets were exclusive examples of miniatures like embroideries, done using satin stitches, stands out from other objects produced at various centers of Himalayan region and other centers. The other thing is significant here is that this was the period (1871 to 1903) when embroidered rumals or handkerchiefs were embroidered at many regions of Punjab Hill states. However, due to its qualities the Chamba, Kangra and Kullu handkerchiefs got noticed and recorded. Politically this period was the rise of Chamba state and Raja Sham Singh (r.1873-1904) was the ruler. His contribution in field of art and culture is very significant. Rumals or hangings produced during this phase are preserved in two museums, known so far. These are Victoria and Albert, London (hereafter as V&A) and Indian Museum, Kolkata (hereafter as IM). The records of TM do not specifically use the Chamba rumals term but refers embroideries from Himalayan region. In the case of V&A name of Chamba, Nurpur and Baghal or Arki have been mentioned for these coverlets. Scholars like Mulk Raj Anand, A.K. Bhattacharyya, Kamla Devi Chattopadhya, Jasleen Dhamija, V.C. Ohri, Subhashini Aryan and others have mentioned about Chamba rumals and it was practiced in the region in the entire hill region in 180,-19th centuries." V.C. Ohri records that Mandi, Suket and Bilaspur embroidery is different from Chamba. Further he say that chamba rumal style of embroidery was declined at Kangra, Guler, Nurpur, Basohli etc. due to withdrawal of patronage in the first half of 19th century. S. Aryan mentions such embroidery was practiced at Kangra, Nurpur, Kulu, Mandi, Bilaspur, Suket (Sundernagar), Chamba, Basohli, Jammu and other parts of Himachal Pradesh, Jammu Punjab region. These scholars have identified centers for production of rumals and hangings with the help of miniature paintings. Some of the prominent were Kangra, Nurpur, Kulu, Mandi, Bilaspur, Suket (Sundernagar), Chamba and others (present Himachal Pradesh). Apart from Himachal, these were practiced in Jammu, Basohli, and other parts of Jammu state and to some extent in Punjab region also. All these references clearly indicate the valuable contribution of Rajas' of Chamba state in preserving this embroidery skill and hence it flourished in the region during mid-eighteenth century. The special contribution of Raja Gopal Singh, Raja Sham Singh and Raja Sir Bhuri Singh (r.1904-1919) is great, who took special interest to popularize the coverlets. This is also the known fact that Raja Raj Singh (r. 1764-1694) annexed Basohli (in 1782) and Kangra (in 1788). Thereafter many painters and artists, who were losing support from these Hill states, got the royal patronage from Chamba Raja's, as by this time Chamba state became stronger. It seems Chamba Ranis' and ladies of rank were involved in creating coverlets and hangings with the support of Rajas, who were propagating these coverlets or hangings in the courts of East India Company, display in exhibitions, gifted to the visitors of their state. Another important fact is that Raja's of Chamba had matrimonial allegiances with Basohali, Kullu, Mandi, Jammu, Jasrota, Guler, Kangra, Nurpur. They were married to princess of these different states and also their daughters were married to other hill states prince and kings (for details please see the chart). Moreover, the artists who were doing the line drawing of classical style of coverlets were many times the court painters of these states and often keep shunting for the sack of royal patronage. Therefore, many themes appeared in Rang Mahal of Chamba Palace, Pahari Paintings also appeared on coverlets.°Themes of Guler, Kangra school paintings also appeared in coverlets. Many such important and significant coverlets and hangings were embroidered in classical style, as the line drawing were done by the court artists, may be as per the guidelines of royal court and under direct supervision of royal women. Therefore, as these handkerchiefs were embroidered and used all over the Himalayan region, also in Jammu and Punjab region. Since these were practiced in many hill states, therefore will be more appropriate to use the term `Pahari coverlets' instead of `Chamba rumals ' as suggested by Dr. Subhashini Aryan, who had done a lot of work on this subject. Satin Stitch of Himalayan Region: Possible Connection Most of the scholars and researchers agreed the use of dorukha or double satin stitches for embroidering the miniature painting like coverlets or hangings is exclusive to the Himalayan region. But scholars do not have one view on the origin of satin stitch and believe that on Himalayan embroideries there is influence from outside, which could be Chinese, Persian/Turkish. There is the possibility that maybe it has indigenous roots, perhaps, Rajputana, and it has been nurtured by the Turks, Tughlaq, Mughal and British, who came in the region for various reasons. Chinese: The Religious Connection The costumes, religious textiles and miscellaneous items were embroidered in China with many different kinds of stitches and satin stitch is one of them. The earliest available example of satin stitch Chinese embroidery is found from a tomb of the state of Chu of the Warring Sates Period (475-221 BCE). It is embroidered with a dragon-and-phoenix design and more than 2000 years' old. This tradition continued in later period also and several embroidered textiles have been reported from China and stitch satin embroidered evidences are reported from Yung (1279-1368) and Ming period (1368-1644). The beginning of fifteenth century evident embroidered religious hangings and panels especially from the reign of emperor Yongle (r.1402-1424). Emperor Yongle was one of the great emperor of Ming dynasty (1368-1644), whose cultural, commercial and political activities gave a new dimension. He had high regards for Buddhism and established relations with Tibet, although he respects the other religions also. Constant exchange of art ideas and techniques between China and Tibet can be seen during this phase. This is evident in the art works, decoration of several religious places and embroidered hangings were one of them. Several big hangings and small votive panels were embroidered with Buddhist deities, with satin, couching and running stitches on satin silk base fabric. Many of these hangings show the theme and its treatment reflect the influence of Nepali-Tibet style and the workmanship shows the Chinese origin. Such hangings/banners were perhaps, commissioned by emperor, as four complete banners with Yongle inscriptions are known so far. [caption id="attachment_188179" align="alignright" width="238"]