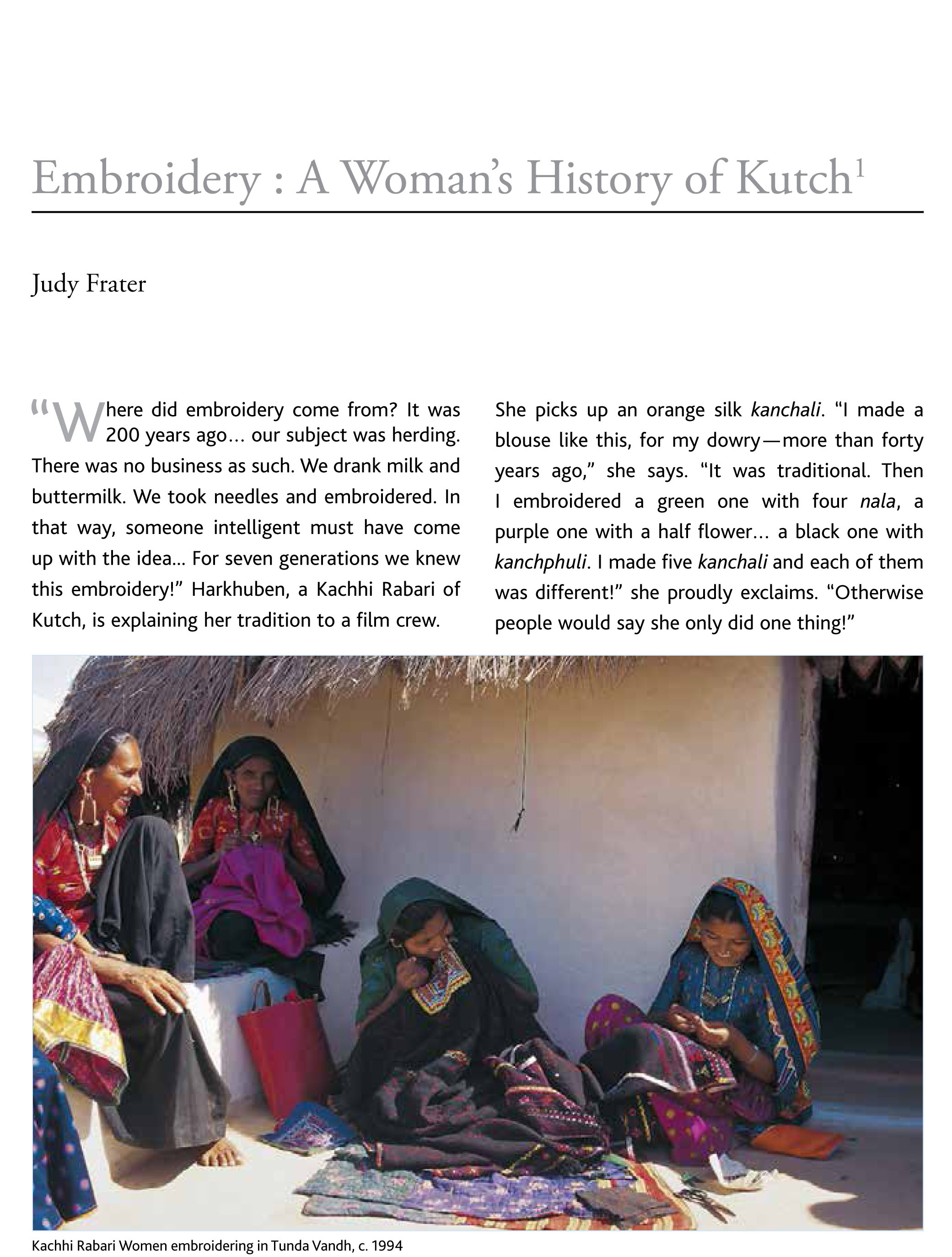

JOURNAL ARCHIVE

Noah Seelam/AFP

All over social media these days, people are making 100 Sari pacts to wear the elegant garment at least 100 times this year. It's a curious sad irony that, just as so many women seem to be rediscovering the sari, the government seems bent on putting an end to its handloom incarnation.

A move is on to repeal The Handloom Reservation Act, which since 1985 has been protecting traditional handloom weaves, especially saris, from being copied by their machine-made and powerloom competitors. It was a small but important protection for handloom weavers, who otherwise struggle to survive. Their yarn, their designs and their markets are under attack.

Now the powerful powerloom lobby is agitating to have this Act withdrawn. Meetings and consultations have been held, largely without the inclusion of handloom-sector representatives, and our representations and queries have gone unanswered.

One powerloom lobbyist at the meeting allegedly said that "we have progressed from the firewood chula to gas and electric stoves. If we need to hang on to technologies from our grandparents times, it is a mark of regression. Our children will laugh at us." Another claimed that "the customer prefers cheaper powerloom sari".

We need to challenge the statement that handloom is not viable in the market. This ignores the facts. Obviously the market has shifted from rural to urban, but it is a growing one, and we have figures to support that. This despite problems faced by weavers in yarn procurement and market access. Over the last five years the sale of handlooms has actually increased. Huge sales and eager footfalls at exhibitions organised by Dastkar, Sanatkada, and the Crafts Councils bear witness. Globally too, as understanding of the ecological properties and design virtuosity of hand-spun and hand-woven textiles grows, more and more international buyers look to India as a source. How tragic that instead of investing in this potential we are seeking to destroy it.

So why not powerloom, the lay person may ask. Isn't it cheaper, quicker and less laborious to weave?

To say that because we have powerlooms, we don't need handlooms is really so silly. To take the chula analogy, it's like saying because we have microwave ovens we don't need tandoors. Each serves its own unique purpose, and it's the Indian tandoor that creates our unique Indian cuisine and draws tourists and foodies. The handloom can create thousands of distinctive regional weaves and designs that no powerlooms can replicate, plus a tactile wonderful drape that is also irreplaceable by mechanised means.

How tragic that instead of investing in this potential we are seeking to destroy it.

If we remove the protection and incentives for handloom weavers to continue weaving their traditional products and saris, we would suddenly be bereft of our past. Each weave has a cultural tradition and a story, each one links us to our social and cultural roots. We would literally be naked without them.

Handloom lovers, it's time to raise your voice.

Noah Seelam/AFP

All over social media these days, people are making 100 Sari pacts to wear the elegant garment at least 100 times this year. It's a curious sad irony that, just as so many women seem to be rediscovering the sari, the government seems bent on putting an end to its handloom incarnation.

A move is on to repeal The Handloom Reservation Act, which since 1985 has been protecting traditional handloom weaves, especially saris, from being copied by their machine-made and powerloom competitors. It was a small but important protection for handloom weavers, who otherwise struggle to survive. Their yarn, their designs and their markets are under attack.

Now the powerful powerloom lobby is agitating to have this Act withdrawn. Meetings and consultations have been held, largely without the inclusion of handloom-sector representatives, and our representations and queries have gone unanswered.

One powerloom lobbyist at the meeting allegedly said that "we have progressed from the firewood chula to gas and electric stoves. If we need to hang on to technologies from our grandparents times, it is a mark of regression. Our children will laugh at us." Another claimed that "the customer prefers cheaper powerloom sari".

We need to challenge the statement that handloom is not viable in the market. This ignores the facts. Obviously the market has shifted from rural to urban, but it is a growing one, and we have figures to support that. This despite problems faced by weavers in yarn procurement and market access. Over the last five years the sale of handlooms has actually increased. Huge sales and eager footfalls at exhibitions organised by Dastkar, Sanatkada, and the Crafts Councils bear witness. Globally too, as understanding of the ecological properties and design virtuosity of hand-spun and hand-woven textiles grows, more and more international buyers look to India as a source. How tragic that instead of investing in this potential we are seeking to destroy it.

So why not powerloom, the lay person may ask. Isn't it cheaper, quicker and less laborious to weave?

To say that because we have powerlooms, we don't need handlooms is really so silly. To take the chula analogy, it's like saying because we have microwave ovens we don't need tandoors. Each serves its own unique purpose, and it's the Indian tandoor that creates our unique Indian cuisine and draws tourists and foodies. The handloom can create thousands of distinctive regional weaves and designs that no powerlooms can replicate, plus a tactile wonderful drape that is also irreplaceable by mechanised means.

How tragic that instead of investing in this potential we are seeking to destroy it.

If we remove the protection and incentives for handloom weavers to continue weaving their traditional products and saris, we would suddenly be bereft of our past. Each weave has a cultural tradition and a story, each one links us to our social and cultural roots. We would literally be naked without them.

Handloom lovers, it's time to raise your voice.

Issue #10, 2023 ISSN: 2581- 9410 Although we are a team of transportation designers we ventured into the world of footwear due to the realization of design’s transformative power. Prior to establishing Earthen Tunes, our trio collaborated on a highly successful wheelchair project during our graduation thesis and this experience enlightened us to the immense potential of design thinking to positively impact the lives of Indians. Our exploration revealed a dearth of authentically Indian designs, as much of what we encounter is influenced by the West. This prompted us to question whether we could create something entirely new, unencumbered by external influences, to address the specific challenges faced by Indians. Following the success with the wheelchair project, the founders Santosh Kocherlakota, Nakul Lathkar and Vidyadhar Bhandare met in 2018 with a newfound purpose: to make a difference in rural India. While footwear for farmers was not an immediate decision, we embraced the essence of design thinking, which urged us to immerse ourselves in rural India, rather than merely analysing articles from the comfort of our homes. SEEDHE CARS SE CHAPPAL?- Why Earthen Tunes?

At Earthen Tunes, we understood that true innovation stems from first-hand experiences and empathy. and we ventured into the heart of rural India to grasp the nuances of everyday life, the challenges faced by our fellow countrymen and the essence of their unique identity.

The next sections talk about our journey of how we were able to create these farmer shoes from a traditional craft

BHAI BOHOT PROBLEM HAIN - RURAL INDIA JOURNEY (SUMMER 2018)

At Earthen Tunes, we understood that true innovation stems from first-hand experiences and empathy. and we ventured into the heart of rural India to grasp the nuances of everyday life, the challenges faced by our fellow countrymen and the essence of their unique identity.

The next sections talk about our journey of how we were able to create these farmer shoes from a traditional craft

BHAI BOHOT PROBLEM HAIN - RURAL INDIA JOURNEY (SUMMER 2018)

In the first part of our journey we delved into the intricate world of the farmer-to-food supply chain i.e. we tried to understand the complete farming supply chain from sowing to until the food ends up on our plate.

We started off our journey, from Nandad, Nakul’s ’ hometown and proceeded further into rural Maharashtra to places such as Wardha, Baramati

Immersed in the field, we sought to grasp the challenges faced by farmers, particularly during the scorching summer months.

Conversations flowed freely as we engaged with them, without any set agenda other than understanding their experiences. To gain deeper insights, we even tried our hand at activities such as operating tractors, experiencing first-hand the nuances and difficulties faced by these dedicated individuals.

In the first part of our journey we delved into the intricate world of the farmer-to-food supply chain i.e. we tried to understand the complete farming supply chain from sowing to until the food ends up on our plate.

We started off our journey, from Nandad, Nakul’s ’ hometown and proceeded further into rural Maharashtra to places such as Wardha, Baramati

Immersed in the field, we sought to grasp the challenges faced by farmers, particularly during the scorching summer months.

Conversations flowed freely as we engaged with them, without any set agenda other than understanding their experiences. To gain deeper insights, we even tried our hand at activities such as operating tractors, experiencing first-hand the nuances and difficulties faced by these dedicated individuals.

Throughout our six to seven-month journey, we encountered remarkable individuals engaged in even more transformative initiatives. One such person was Mr. Subash Palakar, a leading advocate of natural farming who also advises the Indian government. Attending his sessions broadened our perspective, igniting a spark of inspiration within us.

Another impactful experience was our participation in a run organized by the Paani Foundation, spearheaded by Mr. Aamir Khan. This initiative aimed to combat drought in rural Maharashtra by encouraging villagers to partake in activities that promote rainwater harvesting. Witnessing these endeavours only fueled our determination to create something impactful.

Throughout our six to seven-month journey, we encountered remarkable individuals engaged in even more transformative initiatives. One such person was Mr. Subash Palakar, a leading advocate of natural farming who also advises the Indian government. Attending his sessions broadened our perspective, igniting a spark of inspiration within us.

Another impactful experience was our participation in a run organized by the Paani Foundation, spearheaded by Mr. Aamir Khan. This initiative aimed to combat drought in rural Maharashtra by encouraging villagers to partake in activities that promote rainwater harvesting. Witnessing these endeavours only fueled our determination to create something impactful.

As the harvest season arrived, we explored the subsequent steps of the supply chain, witnessing the intricate economy that unfolds, from grain storage to the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC).

The visit to APMC revealed the disparities and exploitation faced by farmers at the hands of middlemen

Our exploration continued into the vast godowns, where we unravelled the logistics involved.

Eye-opening discoveries awaited us, such as the distressing reality of food wastage during storage and the delayed payment farmers endure after delivering their produce.

As the harvest season arrived, we explored the subsequent steps of the supply chain, witnessing the intricate economy that unfolds, from grain storage to the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC).

The visit to APMC revealed the disparities and exploitation faced by farmers at the hands of middlemen

Our exploration continued into the vast godowns, where we unravelled the logistics involved.

Eye-opening discoveries awaited us, such as the distressing reality of food wastage during storage and the delayed payment farmers endure after delivering their produce.

The warmth and openness of the local communities we encountered along the way were invaluable. Their willingness to share their experiences left a lasting impression, opening our eyes to the realities they face.

Upon returning from this transformative research, we meticulously compiled the problem statements we had gathered. Initially faced with a multitude of challenges, we narrowed our focus to five core issues that embody the essence of Earthen Tunes. These will shape our journey over the next decade, driving us to make a lasting difference in the lives of those who cultivate our sustenance.

BINA CHAPPAL KE?- FOOTWEAR RESEARCH( MONSOON 2018)

The warmth and openness of the local communities we encountered along the way were invaluable. Their willingness to share their experiences left a lasting impression, opening our eyes to the realities they face.

Upon returning from this transformative research, we meticulously compiled the problem statements we had gathered. Initially faced with a multitude of challenges, we narrowed our focus to five core issues that embody the essence of Earthen Tunes. These will shape our journey over the next decade, driving us to make a lasting difference in the lives of those who cultivate our sustenance.

BINA CHAPPAL KE?- FOOTWEAR RESEARCH( MONSOON 2018)

Of the shortlisted problems the first one we set out to solve was the issue of farmers walking barefoot. While there may be a romantic notion associated with barefoot walking, claiming a connection to Mother Earth and promoting good health, the reality for farmers today is quite different.

The soil and ecological conditions they encounter actually do more harm than good.

Imagine the common sight in rural areas: cracked and calloused feet, plagued by fungal infections, and even

snake bites. Farming, being a man-made endeavour, creates unique challenges that necessitate protective footwear

Of the shortlisted problems the first one we set out to solve was the issue of farmers walking barefoot. While there may be a romantic notion associated with barefoot walking, claiming a connection to Mother Earth and promoting good health, the reality for farmers today is quite different.

The soil and ecological conditions they encounter actually do more harm than good.

Imagine the common sight in rural areas: cracked and calloused feet, plagued by fungal infections, and even

snake bites. Farming, being a man-made endeavour, creates unique challenges that necessitate protective footwear

The common suggestion to use gum boots or Western-style footwear like Woodland fails to address the specific needs of Indian farmers. Pushing such products into the Indian market proves flawed, as farmers often end

up not wearing anything at all.

The common suggestion to use gum boots or Western-style footwear like Woodland fails to address the specific needs of Indian farmers. Pushing such products into the Indian market proves flawed, as farmers often end

up not wearing anything at all.

In quest for the perfect material our journey began again in Wardha, where we partnered with the NGO Dhara Mithr. Their generous support allowed us to delve into the world of natural fibres and craft our initial footwear prototypes using jute, banana, and cotton fibres. These prototypes showcased intriguing properties but fell short of meeting our stringent criteria for farmer footwear

In quest for the perfect material our journey began again in Wardha, where we partnered with the NGO Dhara Mithr. Their generous support allowed us to delve into the world of natural fibres and craft our initial footwear prototypes using jute, banana, and cotton fibres. These prototypes showcased intriguing properties but fell short of meeting our stringent criteria for farmer footwear

Undeterred, we pressed on to our next destination—Kerala. Here, we had the privilege of collaborating with the remarkable NGO KIDS, located in the picturesque town of Kottapuram. Operated by a local church, KIDS empowers single and widowed women by providing them with opportunities for skill development.

Working side by side with these talented artisans, we explored unconventional materials such as screw pine, water hyacinth, and coir.

During our time in Kottapuram, we also discovered an enthralling museum that showcased a treasure trove of natural fibres and intricate weaves. Unfortunately, despite the rich heritage and craftsmanship on display, the demand for these woven marvels had waned over time, highlighting the need for greater recognition and support.

Undeterred, we pressed on to our next destination—Kerala. Here, we had the privilege of collaborating with the remarkable NGO KIDS, located in the picturesque town of Kottapuram. Operated by a local church, KIDS empowers single and widowed women by providing them with opportunities for skill development.

Working side by side with these talented artisans, we explored unconventional materials such as screw pine, water hyacinth, and coir.

During our time in Kottapuram, we also discovered an enthralling museum that showcased a treasure trove of natural fibres and intricate weaves. Unfortunately, despite the rich heritage and craftsmanship on display, the demand for these woven marvels had waned over time, highlighting the need for greater recognition and support.

Continuing our quest, we collaborated with the Central Coir Research Institute (CCRI) in Allepay. Here, we honed our expertise in coir, while also experimenting with water hyacinth and sisal fibre to make footwear

Although these creations were aesthetically pleasing and offered a delightful wearing experience, they still fell short of meeting our ultimate objective: designing footwear specifically tailored for the needs of farmers

Despite our exhaustive experimentation with approximately 14 to 15 different fibres, it was an encounter in Maharashtra that introduced us to the elusive wool possessing the very properties we had been seeking all along. Intrigued by its potential, we eagerly delved into exploring the wonders this fibre held, paving the way for our next phase of innovation.

DESI MAGIC -THE WOOL JOURNEY (WINTER 2018 - SUMMER 2019)

Continuing our quest, we collaborated with the Central Coir Research Institute (CCRI) in Allepay. Here, we honed our expertise in coir, while also experimenting with water hyacinth and sisal fibre to make footwear

Although these creations were aesthetically pleasing and offered a delightful wearing experience, they still fell short of meeting our ultimate objective: designing footwear specifically tailored for the needs of farmers

Despite our exhaustive experimentation with approximately 14 to 15 different fibres, it was an encounter in Maharashtra that introduced us to the elusive wool possessing the very properties we had been seeking all along. Intrigued by its potential, we eagerly delved into exploring the wonders this fibre held, paving the way for our next phase of innovation.

DESI MAGIC -THE WOOL JOURNEY (WINTER 2018 - SUMMER 2019)

Among the myriad challenges we faced in our pursuit of natural fibres for footwear, one obstacle stood out prominently: -“water resistance”.

That’s when we stumbled upon a truly fascinating material that repelled water effortlessly. To demonstrate its remarkable properties, we even placed it atop our heads, and poured water over it and to our

surprise the water didn’t pass through.

Curiosity piqued, we delved further into the world of wool, particularly the traditional blankets crafted by certain communities known to endure for 20 to 25 years. Intrigued by this longevity, we embarked on a journey to witness the process first-hand.

Among the myriad challenges we faced in our pursuit of natural fibres for footwear, one obstacle stood out prominently: -“water resistance”.

That’s when we stumbled upon a truly fascinating material that repelled water effortlessly. To demonstrate its remarkable properties, we even placed it atop our heads, and poured water over it and to our

surprise the water didn’t pass through.

Curiosity piqued, we delved further into the world of wool, particularly the traditional blankets crafted by certain communities known to endure for 20 to 25 years. Intrigued by this longevity, we embarked on a journey to witness the process first-hand.

During our exploration, we immersed ourselves in wool economy. We discovered the source of the fleece, delved into the quality standards, and uncovered the age-old practices employed in blanket making

The wool economy serves as a vital source of income for pastoral communities across India. These indigenous wool varieties are primarily reared by the Kuruma, Kuruba, Golla and other specific communities residing in the Deccan region, encompassing Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra.

Interestingly, both men and women participate in the wool economy.

During our exploration, we immersed ourselves in wool economy. We discovered the source of the fleece, delved into the quality standards, and uncovered the age-old practices employed in blanket making

The wool economy serves as a vital source of income for pastoral communities across India. These indigenous wool varieties are primarily reared by the Kuruma, Kuruba, Golla and other specific communities residing in the Deccan region, encompassing Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra.

Interestingly, both men and women participate in the wool economy.

For instance, the shearing of wool is entrusted to the skilled katregar community, while women take charge of carding and spinning the fibres within their homes. Subsequently, the men weave the wool into intricate blankets. The entire process typically spans 10 days, with weaving alone requiring four to five days. Notably, every element employed in this craft is eco-friendly, and the looms utilized are among the oldest pit looms in the world

You’ll find the tools used here such as—a hand held spindle for yarn making, a scissor for wool shearing and a brush for applying tamarind kernel paste to reduce coarseness and enhance water resistance.

For instance, the shearing of wool is entrusted to the skilled katregar community, while women take charge of carding and spinning the fibres within their homes. Subsequently, the men weave the wool into intricate blankets. The entire process typically spans 10 days, with weaving alone requiring four to five days. Notably, every element employed in this craft is eco-friendly, and the looms utilized are among the oldest pit looms in the world

You’ll find the tools used here such as—a hand held spindle for yarn making, a scissor for wool shearing and a brush for applying tamarind kernel paste to reduce coarseness and enhance water resistance.

Sadly, this once-thriving craft faces decline as plastic alternatives replace the coarse wool blankets. What was once a bustling market in Karnataka is dwindling rapidly. Currently, the average age of weavers in this trade is 60 years, and there are no apprentices to carry the craft forward.

Sadly, this once-thriving craft faces decline as plastic alternatives replace the coarse wool blankets. What was once a bustling market in Karnataka is dwindling rapidly. Currently, the average age of weavers in this trade is 60 years, and there are no apprentices to carry the craft forward.

In fact, the state of the carding machine pictured here, installed by the government two decades ago, reflects the current state of the craft. With minimal use restricted to three months of the year, neglect has taken its toll.

However, we see a glimmer of hope—a potential synergy between our footwear needs and the demand for this remarkable material. By incorporating this wool into our shoes, we believed we could breathe new life into the craft, benefiting both farmers and the pastoral communities

YEH NAHI BANEGI - SHOE MANUFACTURING

In fact, the state of the carding machine pictured here, installed by the government two decades ago, reflects the current state of the craft. With minimal use restricted to three months of the year, neglect has taken its toll.

However, we see a glimmer of hope—a potential synergy between our footwear needs and the demand for this remarkable material. By incorporating this wool into our shoes, we believed we could breathe new life into the craft, benefiting both farmers and the pastoral communities

YEH NAHI BANEGI - SHOE MANUFACTURING

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eager to explore the potential for large-scale production, we contemplated engaging Women Self-Help Groups (SHGs) as well to bring in an aspect of circularity

Working in partnership with Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in both Chennai and Hyderabad, we encountered a promising revelation. In Chennai, the women of an SHG demonstrated remarkable skill by crafting a pair of our shoes in just one day.

Despite facing language barriers due to our limited fluency in Tamil, we effectively conveyed our design ideas, resulting in a clear understanding of the pattern and by incorporating principles of symmetry, user-friendly marking techniques and necessary tools, we observed the women’s impressive expertise in shoe production.

While this development was encouraging, we recognized the need for further refinement to ensure large-scale production feasibility. This concept remains an integral part of our grand vision, and we aspire to revisit it in the future.

BECH KE DIKHAO-SHOE PILOT TESTING (MONSOON 2019)

Eager to explore the potential for large-scale production, we contemplated engaging Women Self-Help Groups (SHGs) as well to bring in an aspect of circularity

Working in partnership with Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in both Chennai and Hyderabad, we encountered a promising revelation. In Chennai, the women of an SHG demonstrated remarkable skill by crafting a pair of our shoes in just one day.

Despite facing language barriers due to our limited fluency in Tamil, we effectively conveyed our design ideas, resulting in a clear understanding of the pattern and by incorporating principles of symmetry, user-friendly marking techniques and necessary tools, we observed the women’s impressive expertise in shoe production.

While this development was encouraging, we recognized the need for further refinement to ensure large-scale production feasibility. This concept remains an integral part of our grand vision, and we aspire to revisit it in the future.

BECH KE DIKHAO-SHOE PILOT TESTING (MONSOON 2019)

As our vision gained momentum, we approached IIT Madras, seeking both financial support and incubation.

Though intrigued by our idea, they were cautiously optimistic, desiring proof of its viability. Their challenge to us was clear: demonstrate market viability by selling a few pairs of our shoes.

If successful, IIT Madras would provide us with the incubation opportunity.

For manufacturing the pilot shoes, we ventured to Ambur, collaborating with a local manufacturer to produce 30 pairs of our shoes (design shown in picture)

As our vision gained momentum, we approached IIT Madras, seeking both financial support and incubation.

Though intrigued by our idea, they were cautiously optimistic, desiring proof of its viability. Their challenge to us was clear: demonstrate market viability by selling a few pairs of our shoes.

If successful, IIT Madras would provide us with the incubation opportunity.

For manufacturing the pilot shoes, we ventured to Ambur, collaborating with a local manufacturer to produce 30 pairs of our shoes (design shown in picture)

|

|

Subsequently, our goal became associating ourselves with IIT and the immense opportunities that would arise from such a partnership.

Fortunately, IIT Madras reviewed our pilot results and agreed to incubate our venture, providing us with a robust platform to showcase our products at various forums. The exposure garnered valuable feedback, enriching our journey further

LIFT OFF - PRODUCT LAUNCH (AUGUST 2021-PRESENT)

Subsequently, our goal became associating ourselves with IIT and the immense opportunities that would arise from such a partnership.

Fortunately, IIT Madras reviewed our pilot results and agreed to incubate our venture, providing us with a robust platform to showcase our products at various forums. The exposure garnered valuable feedback, enriching our journey further

LIFT OFF - PRODUCT LAUNCH (AUGUST 2021-PRESENT)

|

|

|

|

After multiple Iterations we have launched YAAR shoes into the market. The YAAR range consists of 2 variants -Himachal wool and Deccani wool. The YAAR shoe is also cross subsidised for the farmers to make it more affordable for them

After multiple Iterations we have launched YAAR shoes into the market. The YAAR range consists of 2 variants -Himachal wool and Deccani wool. The YAAR shoe is also cross subsidised for the farmers to make it more affordable for them

|

|

|

|

|

|

Our shoes have also been supported by Hon Minister KTR garu of Telangana Government and Prof. Ashok Jhunjunwala from IIT Madras

Our shoes have also been supported by Hon Minister KTR garu of Telangana Government and Prof. Ashok Jhunjunwala from IIT Madras

Earthen Tunes has impacted to lives of over 2000 farmers and have provided over 6000 hours of employment to about 11 weaving and allied activity clusters

We plan to reach over 10000 farmers by the end of 2023-24 and provide livelihood to about 20 weaving clusters across the Deccan region, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand

Earthen Tunes has impacted to lives of over 2000 farmers and have provided over 6000 hours of employment to about 11 weaving and allied activity clusters

We plan to reach over 10000 farmers by the end of 2023-24 and provide livelihood to about 20 weaving clusters across the Deccan region, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand

The Contemporary Significance of Bamboo

Bamboo is being rediscovered by mankind in the age of the information revolution, environmental consciousness and space exploration. As a potential renewable resource and an inexhaustible raw material, if properly managed, bamboo could transform the way we think about and use man-made objects to improve the quality of life. In many economically deprived countries bamboo could provide the answer to the distressing problems of employment generation and of providing basic shelter and amenities in an affordable and dignified manner. It also holds promise of the spawning of a host of new industries that are ecologically responsible while providing for the manufactured artefacts for a new age. An agro-industrial infrastructure could well bridge the urban-rural divide in many regions of the world. Can this promise be realised?Notwithstanding the complexity and magnitude of these assumptions it seems appropriate that these propositions need to be addressed with all seriousness and a multi-disciplinary approach be developed to realise this latent potential. The design disciplines that have emerged in this century have been increasingly drawing on the systems metaphor to cope with the complexity in the real world of resource identification and problem solving. It is here that the lessons from the Bamboo Culture could provide a direction to mankind. Above all the subtle messages embedded in the Bamboo Culture can be re-articulated by mankind today with the aid of some of our very powerful analytical and conceptual tools available to us in this age. Never before has mankind been so fortunate to be in the possession of such a vast and widely networked information base along with the capacity to process this knowledge base for the benefit of all mankind.Last year, I was fortunate to be a member of an editorial group that met at Singapore to assemble an annotated bibliography on the engineering and structural properties and applications of bamboo. The group led by Dr Jules Janssen of the Eindhoven University of Technology worked for four days at the IDRC office (International Development Research Centre, Canada) accessing satellite databases and team contributions to complete the editorial task which is now in production. IDRC's massive investments in bamboo research around the globe are indicative of the resurgent interest in bamboo. These researches however, need to be given a larger framework to make the individual research efforts more meaningful and to enable us to pattern these contributions in a holistic perspective. Hence I shall use this opportunity to elaborate the ideas that I had barely sketched out in my contribution to that editorial effort. Further, I shall try and link these to the deeper concerns that have grown over the years as a design teacher at India's premier design institution while grappling with the immense problems faced in India's developmental efforts along with the conviction that design as a discipline has a pivotal role to play in alleviating some of these seemingly insoluble problems of immense complexity.Bamboo: A Personal Journey

My own interest has been in the structural use of bamboo which extends from large structures including houses and bridges, that is structures of an architectural scale, as well as the application of bamboo in furniture and small craft products. Being an industrial designer interested in the use of bamboo, particularly with reference to its conversion into useable products of everyday value, I have been focussing on the way bamboo has been used by local communities in India, particularly with reference to the northeastern states of India. I have surveyed the bamboo growing regions of India intensively with my colleagues at the National Institute of Design and the results of this research have been published in our book titled Bamboo and Cane Crafts of Northeast India.Bamboo is found in most parts of India and has been traditionally used to solve a variety of structural and constructional problems in the Indian subcontinent. A very interesting observation that we have made in the course of our studies is the nexus between the form of bamboo structures and a set of influencing parameters. These include the variety in types of local bamboo species, its distribution and variability over climatic zones, the availability of particular species and its translation into products and structures for local application. These factors have all had an overriding cultural connotation particularly in the detailing and formal expressions that are chosen by local communities in solving their structural and constructional problems. Product variability in form and structure seems to be quite independent of product function and dominated by considerations of cultural differentiation expressing a need for an unique identity at the community level. Properties of material and structure, and their appropriate interpretation in product detailing are a high-point of almost every traditional product that has emerged from a very long process of cultural evolution. These findings have convinced me that we need to understand this material at many levels simultaneously to be able to use it effectively.We have followed up our field research work with several attempts dealing with the design of contemporary products and structures using bamboo. Through these experiences we have further confirmed the need for a very precise understanding of the physical and mechanical properties of bamboo. However, I would also like to stress that in order to ensure its successful utilisation over diverse climatic and cultural zones these physical and mechanical properties need to be carefully juxtaposed with cultural and formal practices that are evident in the expressions of local communities. In order to bring about a simultaneous correlation between the various types of information that would be required by any engineer, designer or local craftsman to utilise this raw material in situations such as ours it would perhaps be important at some stage to reorient and enlarge the scope of the ongoing research and development work to include several aspects relating to the cultural dimensions in the use and conversion of bamboo into useable products and structures.The purpose of the International Bamboo Culture Forum at Oita Japan as stated by Dr. Shin'ichi Takemura is to develop an agenda for the setting up and providing a focus for the development of design activities that are ecologically responsive and humanely sensitive. This conference in Oita which is one of a series of efforts planned to set up the agenda for the proposed Asian Design Centre gives me the unique opportunity to connect and reflect on two of my favourite topics, that is, Bamboo and Design. Firstly I shall spell out the issues and messages that map out the boundaries of the Bamboo Culture after which we can explore the various dimensions of the new awareness relating to the use of the systems metaphor in design and their mutual interdependence.

Knowledge Base of the Bamboo Culture

The manner in which bamboo has been traditionally used by the people in India, China, Japan and several other Asian countries demonstrates a very deep understanding of the workings of ecological principles and the subtle connections between human endeavour and the environment. In our search for sophistication we seem to have lost our tenuous links with the life sustaining processes on earth and seem to be madly accelerating both socially and technologically in an impossible to sustain direction. Total replacement of products of a throw-away culture is unfortunately preferred to the repair and continuous maintenance that is practised in the Bamboo Culture. This has resulted in massive garbage heaps accumulating in our backyards and the creation of museums of garbage. Can we afford to head in this direction? The advanced industrial nations of the West and unfortunately Japan as well seem to be leading the way to self destruction by the materialist and irresponsible consumerist practices and aspirations that are being driven by systematic propaganda in an information rich world. In India too, we have the educated elite aping these practices and aspiring for similar lifestyles quite unperturbed by the ecological consequences and, seeing their behaviour, our disadvantaged rural brethren too aspire to similar unattainable life goals. It is here that I feel we need to rethink our directions and draw on the lessons of the Bamboo Culture. I am not advocating a return to the past. On the contrary I am very much at ease with the computers and other products of human genius including the conceptual tools of our age. I see hope in trying to bridge these seemingly opposing positions in finding a sustainable direction for the future of man on this planet.

Man's use of bamboo in the development of human civilization perhaps predates the Stone Age and the Iron Age as a study by G Gregory Pope seems to suggest. Pope's thesis based on the study of fossil records of the distribution of animal species when juxtaposed with the occurrence of traces of human settlements over the globe along with other indirect evidence suggests that the Asian regions housed the origin and flowering of human civilizations rooted in the availability of bamboo. If this is so, history will be rewritten to give bamboo a catalytic role in the cradle of human civilization which was overlooked due to lack of any subterranean traces caused by the biodegradable nature of bamboo. The theory is quite plausible and it provides some clues on the prehistoric origins and development of man and shifts the focal point to our region of the world.

These regions of Asia have had an undisturbed association with bamboo and in many inaccessible parts of India and most of other East Asian countries this link survives in the lives and practices of its people even today. These need to be systematically and sympathetically studied by contemporary man to distil the essence of the millennia old wisdom that even today resides in these local associations with bamboo. These proposed studies are not merely aimed at the conservation of archaic practices for the sake of some romantic or sentimental mood. They should be aimed at discovering the larger patterns that lie embedded in the details of each product, practice or ceremony associated with the use of bamboo.

Bamboo: The Tasks Ahead

Keeping this pattern discovering task as the focus of the study and as the overarching objective the other areas of knowledge need to be correlated and systematically interwoven to map the boundaries of the knowledge base that I prefer to call the New Bamboo Culture. Some of these are listed below, and would naturally be elaborated with the intervention of others from a variety of special disciplines.

|

When enumerators from the national Economic Census 2012 knock on your door later this year, give them a special welcome. Census 2012 is going to be hugely significant for CCI and all crafts activist in the country --- and you may well be part of the preparation the enumerators will have gone through in order to do their job. That job is linked to CCI’s “Craft Economics & Impact Study” (CIES) which was completed last year (see Learning Together, Newsletter February 2012). The February Newsletter attempted to keep members informed of developments that have followed the submission of the CEIS to Government, soon after the Study was shared at the Business Meet last August. The Study and its recommendations were then reviewed by a partnership group which came together at the Crafts Museum in New Delhi in September. That was when members of the CEIS team (Raghav Rajagopalan, Gita Ram, Manju Nirula, Shikha Mukherji and I) met with key officials in the Planning Commission and at the Office of the Development Commissioner. CEIS had an impact. Early in March, the Commission called a series of meetings bringing together activists from civil society and a range of Ministries and Departments at the Centre who are (or should be!) concerned with the wellbeing of artisans and their crafts. Those discussions on the CEIS and related experience have proved hugely significant. The CEIS premise (which echoed concerns expressed earlier in discussions with stakeholders leading up to the 12th Five-Year Plan) was accepted that national data currently available on the sector is dangerously inadequate. It does not reflect in any way the size and scale of the contribution which artisans make to the national economy. It was also accepted that unless this foundation of facts is rectified, policies and schemes as well as investment in the craft sector will continue to miss the bus. At the Planning Commission, two decisions were taken that will have far-reaching effect. One was to include crafts and artisans in the 6th Economic Census 2012. Another was to follow the Census with a ‘Satellite Account’ specific to the sector, which will provide details which cannot be captured in the Census 2012 focus on ‘commercial establishments’. Following these decisions, the Central Statistical Organization (CSO) and the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) have looked at CCI for support on next steps. These have included the framing of guidelines and key questions to be used by field enumerators to correctly identify craft activities and artisans, development of tools and materials to be used in the Census process (including in the training of enumerators and their supervisors), a listing of activities and processes involved in 40 selected crafts identified by the DC(H), and linking these to established statistical codes used to classify commercial activities for Census purposes. The materials developed for the Census include generic and state-specific illustrated maps (developed by CCI with a team of researchers coordinated by Vidya and Gita), bringing together available information with the 560 crafts analysed in “Handmade in India” (Aditi and MP Ranjan, NID), using that publication as a key resource. PPTs are also being prepared to use field examples that can sensitise Census staff on the processes and activities involved in craft production, and the numbers/levels of artisans that need to be included in the understanding of ‘artisans’ and craft production. This has been a huge task, carried out by a small team at the CCI office in Chennai, with support from Manju and the Delhi Crafts Council office. The Census 2012 surveys commercial establishments, i.e. of products and services exchanged in the marketplace. The Census will provide broad indicators of the size and contribution of the craft/artisanal sector to the economy. It will include as ‘commercial establishments’ those who produce for market sale and where the activity of respondents represents more than 180 workdays in the year ---- thus excluding many activities in the sector that are beyond these limitations, such as seasonal work that does not extend over 180 days. These exclusions can be of critical importance to craft activists, as well as other details such as the contribution of women artisans, the invisible half of the sector. These important aspects will be covered by the more detailed analysis of the sector to be made through the ‘Satellite Account’ that is to follow the broad outlines revealed by the Census 2012. Hopefully, data from the Census will be enough to provide a wake-up call to the nation on the importance of crafts and artisans, and begin the process of reforming national policies and programmes. The crunching of data emerging from the Census 2012 will take time (60-100 days after the Census’ field process is completed). Therefore there will be ample opportunity to understand and use the data as it emerges so as to influence the Satellite Account process. Studies may be needed in preparation for the Satellite Account, and CCI intends to be an active partner in these preparations. Raghav, Manju and Gulshanji represented CCI at a May 4 meeting at the Planning Commission, where progress on Census/Satellite Account was reviewed. Of particular importance were two issues. One was the understanding that handloom production would be integrated with the Census’ understanding of ‘craft’. Another was the ‘guideline’ that has finally emerged to help describe the sector:

“Handicrafts are items made by hand, mostly using simple tools. While they are predominantly made by hand, some machinery may also be used in the process. Skills are normally involved in such items/activities, but the extent thereof may vary from activity to activity. These items can be functional, artistic and/or traditional in nature”.

The challenge of ‘defining’ crafts and artisans has been a major one. A workable definition had emerged years ago at the time of the 8th Five Year Plan. The CEIS suggested a definition based on it. Things got complicated when the Supreme Court issued its own definition --- one that was directed at resolving export legalities, not at national data requirements! A ‘guideline’ was needed to address a concern within the Planning Commission and the Ministry of Statistics on distinguishing between crafts and other handmade products (papads, pickles, bricks, bidis etc) that Government does not want to include in its understanding of crafts/artisans. The matter came up again at a June 1 meeting at the CSO, attended by Gita, where the Census 2012 time-table was worked out. Field work will begins after the rains in October, continuing till August 2013. The important issue for CCI is to assist the training that will soon begin throughout the country to sensitise enumerators and supervisors to their field tasks. Details of the training process will emerge from a meeting in New Delhi in late June. Meanwhile, CCI has been asked to assist by identifying resource persons in every region who can be associated with the training process, sharing their knowledge of local crafts in the local language. The support of State Councils and other partners will thus be critical as so much now depends on successfully and quickly sensitizing and ‘educating’ enumerators and their supervisors to the sector. By the time this Newsletter appears, several readers will have been contacted and involved. The range of materials being developed in the course of these efforts will also be of great use and benefit to all craft activists. These can help ensure that future planning and field action are more focused. In addition, the Planning Commission is considering research studies that can support the proposed Satellite Account. It has also expressed its concern to better understand the problems and aspirations that are driving artisans today, most particularly those of the younger generation. Here again are opportunities for advocacy, and for the changes we have all felt so necessary in the way official agencies reach out (or fail to reach out) to artisans through existing schemes --- as well as on changes needed within the NGO sector. That, in a nutshell, is where we are today. So keep in mind all that is at stake when Census 2012 comes knocking at your door!Issue #006, Autumn, 2020 ISSN: 2581- 9410 There are many ways in which education can support the personal and creative development of traditional artisans. In this article, we will focus on how these experiences can expand an artist’s view of himself in the world and the possibilities for innovation and self-expression. Education can remove perceptual limits created by limited knowledge of what exists beyond the village and imposed by outsiders’ ideas about indigenous artisans and how to define and evaluate their work. Oaxaca is known around the world as a center of folk art and craft. The state’s sixteen indigenous ethnic groups make up a significant portion of the population and the majority of traditional artisans. The three artisans whose stories we will examine here are all Zapotec and come from traditional villages. In Oaxaca, it is common for villages to be known for a specific craft, and in these villages one can find hundreds or even thousands of individuals who work in the medium and style for which the village is known. While there are subtle differences in the use of color and motif among the artisans of a village, the primary differences between artisans are found in the quality and subtlety of their work, rather than the use of dramatically different materials, techniques or motifs. A relatively small number of artisans have made the decision to innovate in ways that significantly and often dramatically distinguish their work from that of their neighbors. Based on the stories of our three artisans, I propose that access to education and direct interaction with artisans and buyers from outside the local environment can open the eyes of traditional artists to innovation that defines their personal styles. All three were trained in the basics of their craft by their parents and other elders of their communities. The work they produce today, while clearly based in the traditions and aesthetics of their communities, stands out from that of their neighbors in both quality and creativity. They have found ways to successfully develop a personal style and expression in their work, while remaining firmly rooted in the life and traditions of their communities. And they attribute this growth and development, at least in part, to participation in workshops and education programs outside their communities. Before we look at our three artisans and their work, it is important to set the context. In addition to the work created by traditional village artisans, Oaxaca is also known for graphics, painting and other “fine arts” and has produced such world-renowned artists as Rufino Tamayo, Francisco Toledo and Rodolfo Morales. We can understand the way different creative pursuits are viewed by looking at the language used to discuss them. Painting and graphic arts are referred to with the word “arte,” meaning art, while work in pottery, textiles, and other traditional media are called “artesania,” meaning crafts or “the work of artisans.” Historically, “arte” described objects that were purely decorative, while “artesania” described useful objects that were made by hand, originally for local use. However, under colonization, usage developed to reflect not a pure, logical distinction, but a division based also on the history of the artform and the people most associated with it. So “arte” expresses the European tradition of fine arts while “artesania” is seen as the continuation of local, indigenous traditions. Thus, even though the vast majority of work currently created by village artisans is purely decorative and produced only for an outside market, it is considered “artesania” rather than arte, and is viewed and evaluated accordingly. Most people see fine art and traditional craft differently. In fine arts, the focus is on the individual style of the creator and artistic innovation. No matter how competent one’s technique, one cannot become a great painter or sculptor without developing a personal style and aesthetic. In artesania/folk art/traditional craft, on the other hand, the focus is on the connection to tradition. What is important is that the creator is part of a community where others make similar items from similar materials, using similar techniques and motifs. The focus is on conserving cultural and artistic traditions, rather than on self-expression and innovation But how do we interpret this in the Oaxacan context, where the most appreciated and sought after folk art, while tied to earlier local traditions, is made purely for sale outside the community, was developed for export and in many cases involves objects developed in the second half of the 20th Century? While there have been weavers in Teotitlán for thousands of years, for centuries they wove simple blankets and serapes for the local market. Only in the mid-20th century did the Teotitecos start to weave brightly colored rugs and tapestries for sale in Mexico City, the US and beyond. The designs based on the stonework of the ruins of Mitla now considered “traditional” for weaving from Teotitlán were an innovation by the weaver Arnulfo Mendoza in the 1970’s. Today, local rugs and tapestries are rarely used in the village homes, even by those who make their livelihood producing them. Similarly, the highly ornamented black ceramic pieces for which the village of San Bartolo is known represent a tradition developed in the 1950’s in order to create a product attractive to tourists. Before that, local potters used the same clay to create pieces with a matte gray finish used to store consumable liquids. The focus was on making pieces that were durable and would not leak. Today, most pieces created in the workshops of the village will not hold water and are created for purely decorative use by outsiders. There is only a single potter in San Bartolo who routinely makes “apaztles” (large open bowls) for serving Tejate; ollas for storing water; bottles for storing mezcal and colanders for separating corn from its husk when preparing tortillas. So, why do people talk about these items as if they represent ancient traditions and why do those who have set themselves up as arbiters see innovation as a problem, rather than a strength? Based on conversations with curators, funders and other self-appointed “specialists” in Oaxacan craft or folk art, it seems that a major factor is that these people, most of whom come from outside Oaxaca and virtually all of whom are of predominantly European descent, look at art and craft created by indigenous people though a strongly colonial lens that intentionally supports what is perceived as perpetuating tradition and hinders or devalues what is seen as breaking tradition. When I told the director of a group based in America that supports exhibitions of “traditional” Oaxacan folk art, that I was curating an exhibit focusing on innovation in Oaxacan folk art, she said, “Innovation can be a slippery slope.” When I asked why, she answered, “Because the artists don’t always know where to stop.” I wondered why she thought she had the right to decide how much innovation was too much and to believe that traditional artisans are not able to make that decision for themselves. It seems that that well-educated, middle- and upper-class people of European descent from Mexico, the United States and elsewhere have a vested interest in supporting the manufacture of items that they believe are representative of ancient traditions. They want to believe that the indigenous communities in which folk art and craft are made somehow represent an earlier period in human development and that by visiting these communities they can experience something about their own past. This creates a value system that promotes connections to community and past and censors “too much” individual style or self-expression – the very things that are most valued among artists of European descent and those who work in the media and styles derived from European fine arts. The individuals who support this perspective say that their goal is to keep ancient traditions alive. Unfortunately, they either do not realize that many of the traditions they are supporting are relatively recent innovations developed purely in response to outside markets, or perhaps they simply adjust reality to fit what they want to believe. And they never seem to ask why or for whom traditions should be preserved? They say they want to “help the (poor) artisans,” but rarely actually ask artisans what they want or what would be helpful to them and their communities. They seem to think that artisans can make beautiful things but cannot determine what they want and need, what fits within the boundaries of their traditions, or when it is appropriate for them to work outside those boundaries. The creativity of indigenous people is lauded and coveted, but it is assumed that they are somehow less thoughtful or rational and thus unable to determine what serves them. This perspective also wants to believe that while European culture developed, indigenous people are somehow frozen in time. The reality is that in living traditions, innovation and tradition are two sides of a single coin. The traditions create the framework that defines what is possible while innovation allows each maker to respond to changes in the availability of materials, changes in the market and fashion, personal taste and choice, and other factors that are ever changing. And the only valid arbiters of the appropriate boundaries for a living tradition are those who work in that tradition and members of their communities. I believe that the colonial perspective on indigenous art and craft has been a major damper on the development of truly innovative work as those who are drawn to innovation and personal expression have had to fight to get their work seen and promoted. This is finally changing as Oaxacan artists are finding markets for their work among buyers who value the creative, but with most exhibits and publications on Oaxacan art still focusing on what they understand as traditional, this is an ongoing challenge. Now let’s consider our three artisans and the role education played in their professional development. Moises Martinez Velasquez grew up in San Pedro Cajonos, one of the few Oaxacan villages where the tradition of raising silkworms and processing the silk they produce has been kept alive. Moises learned the basics of the process from his elders and is now the leader of a 13-member family cooperative. When Moises was learning to produce silk textiles, the only natural dyes used in the village were Mexican Marigold and Cochineal. All the garments were woven with undyed yarn and some garments were dyed red when they were removed from the loom. At first, the work done by Moises and his family closely resembled that made by other producers in the region.

Moises Martinez Velasquez Huipil. Handspun silk dyed with indigo

Then Moises was invited to a natural dye workshop, hosted by the Textile Museum of Oaxaca and everything changed. The workshop was taught by a traditional dyer from another Oaxacan village, who not only demonstrated how to achieve a wide range of tones with Cochineal by varying the ph of the dye bath, but also demonstrated the use of Indigo, which added blue, purple and green to Moises’ range. Because the workshop focused on wool, Moises had to adapt the recipes he learned to work on silk. After extensive experimentation, he developed a palette that includes many shades of blue, a wide range of pinks, fuchsias, and reds made with cochineal, golden yellows made with Mexican Marigold, and a range of greens and purples created by dyeing with indigo over shades created with cochineal and marigold. The new colors and increased variety led to an immediate increase in sales of the family’s work. From this, Moises learned that providing options beyond those that were considered traditional expanded the market and provided opportunities for increased income. Because Moises took the time and effort to experiment and find the best ways to create a wide range of rich colors on silk, the family’s work stands out from other silk textiles made in the region, whose color range is more limited and less saturated. During this period, Moises also came to see himself as a dyer and to develop pride in his ability to produce colors that were not seen elsewhere.

Moises Martinez Velasquez Huipil. Handspun silk dyed with indigo

Then Moises was invited to a natural dye workshop, hosted by the Textile Museum of Oaxaca and everything changed. The workshop was taught by a traditional dyer from another Oaxacan village, who not only demonstrated how to achieve a wide range of tones with Cochineal by varying the ph of the dye bath, but also demonstrated the use of Indigo, which added blue, purple and green to Moises’ range. Because the workshop focused on wool, Moises had to adapt the recipes he learned to work on silk. After extensive experimentation, he developed a palette that includes many shades of blue, a wide range of pinks, fuchsias, and reds made with cochineal, golden yellows made with Mexican Marigold, and a range of greens and purples created by dyeing with indigo over shades created with cochineal and marigold. The new colors and increased variety led to an immediate increase in sales of the family’s work. From this, Moises learned that providing options beyond those that were considered traditional expanded the market and provided opportunities for increased income. Because Moises took the time and effort to experiment and find the best ways to create a wide range of rich colors on silk, the family’s work stands out from other silk textiles made in the region, whose color range is more limited and less saturated. During this period, Moises also came to see himself as a dyer and to develop pride in his ability to produce colors that were not seen elsewhere.

Moises Martinez Velasquez, Scarf. Handspun silk. Warp ikat dyed with cochineal

Moises Martinez Velasquez, Scarf. Handspun silk. Warp ikat dyed with cochineal

Moises Martinez Velasquez, Huipil. Silk dyed with Mexican marigold, indigo and cochineal

Moises Martinez Velasquez, Huipil. Silk dyed with Mexican marigold, indigo and cochineal

Moises Martinez Velasquez, Huipil. Silk dyed with Mexican marigold, indigo and cochineal

Over several years, Moises also learned to experiment with different ways of applying the dyes in order to create pattern. He saw how dyeing yarn prior to weaving allowed for the creation of multi-colored garments and started experimenting with stripes and plaids in various color combinations. He also participated in ikat workshops at the Textile Museum and learned to adapt the techniques he learned to his family’s work and market. From the first experiments with ikat, he found that while the pieces take longer to produce, they sell very quickly, even at a higher price. Now, most pieces produced by the family are still dyed a single color, but they routinely produce pieces with yarn-dyed stripes and more complex patterns, created with ikat. This expanded range has caught the eye of buyers and collectors not only in Oaxaca, but also at national craft fairs in Mexico and international events in the US. The work created by Moises and his family is now considered by most experts to be the most interesting and highest quality silk created in Oaxaca.

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa grew up in a textile producing family in Teotitlán del Valle. Like most weavers in the village, he first learned to weave rugs when he was quite young. Juan Carlos grew up during a period when natural dyeing was quite limited in Teotitlán, so he was not initially impressed by the options the traditional natural dyes offered and was not particularly interested in working with dyes.

Moises Martinez Velasquez, Huipil. Silk dyed with Mexican marigold, indigo and cochineal

Over several years, Moises also learned to experiment with different ways of applying the dyes in order to create pattern. He saw how dyeing yarn prior to weaving allowed for the creation of multi-colored garments and started experimenting with stripes and plaids in various color combinations. He also participated in ikat workshops at the Textile Museum and learned to adapt the techniques he learned to his family’s work and market. From the first experiments with ikat, he found that while the pieces take longer to produce, they sell very quickly, even at a higher price. Now, most pieces produced by the family are still dyed a single color, but they routinely produce pieces with yarn-dyed stripes and more complex patterns, created with ikat. This expanded range has caught the eye of buyers and collectors not only in Oaxaca, but also at national craft fairs in Mexico and international events in the US. The work created by Moises and his family is now considered by most experts to be the most interesting and highest quality silk created in Oaxaca.

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa grew up in a textile producing family in Teotitlán del Valle. Like most weavers in the village, he first learned to weave rugs when he was quite young. Juan Carlos grew up during a period when natural dyeing was quite limited in Teotitlán, so he was not initially impressed by the options the traditional natural dyes offered and was not particularly interested in working with dyes.

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa, Scarves. Merino and silk dyed with indigo

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa, Scarves. Merino and silk dyed with indigo

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa, Scarf. 100% merino wool dyed with indigo and cochineal.

When Juan Carlos joined a textile collective in the village, he was invited to participate in a workshop on natural dyes, led by a teacher from outside Mexico. This workshop opened his eyes to the range of colors and shades that can be created with a limited number of dyes and got him more excited about the possibilities. He participated in a workshop on growing dye plants that included discussions of how to pick seeds, prepare the earth, plant the seeds, tend to the plants and harvest the dye material. The workshop also included excursions outside Oaxaca to the Museo del Agua in the state of Puebla and an Eco Reserve in the state of Veracruz. Participation in this workshop gave Juan Carlos a vision of possibilities he had never considered. As he relates, most people in the village complete no more than an elementary school education and do not travel far from the village, so their vision is somewhat limited. After participation in these workshops, Juan Carlos began to grow dye plants on his property in the village and also did extensive experimentation with both the dyes that can be collected locally and with Indigo and Cochineal, which he buys in Oaxaca. As he grew more adept in working with the dyes, the range and subtlety of Juan Carlos’ palette grew, along with his interest in working with the dyes. Within a couple of years, he was doing all the dyeing not only for his own weaving, but also for the weaving done by other members of his family.

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa, Scarf. 100% merino wool dyed with indigo and cochineal.

When Juan Carlos joined a textile collective in the village, he was invited to participate in a workshop on natural dyes, led by a teacher from outside Mexico. This workshop opened his eyes to the range of colors and shades that can be created with a limited number of dyes and got him more excited about the possibilities. He participated in a workshop on growing dye plants that included discussions of how to pick seeds, prepare the earth, plant the seeds, tend to the plants and harvest the dye material. The workshop also included excursions outside Oaxaca to the Museo del Agua in the state of Puebla and an Eco Reserve in the state of Veracruz. Participation in this workshop gave Juan Carlos a vision of possibilities he had never considered. As he relates, most people in the village complete no more than an elementary school education and do not travel far from the village, so their vision is somewhat limited. After participation in these workshops, Juan Carlos began to grow dye plants on his property in the village and also did extensive experimentation with both the dyes that can be collected locally and with Indigo and Cochineal, which he buys in Oaxaca. As he grew more adept in working with the dyes, the range and subtlety of Juan Carlos’ palette grew, along with his interest in working with the dyes. Within a couple of years, he was doing all the dyeing not only for his own weaving, but also for the weaving done by other members of his family.

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa, Scarves. Merino dyed with indigo and cochineal and undyed alpaca

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa, Scarves. Merino dyed with indigo and cochineal and undyed alpaca

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa, Scarves. Merino, alpaca and silk dyed with Mexican marigold, cochineal and indigo

In addition to workshops on dyes and dye techniques, Juan Carlos participated in a number of workshops on design, which he says expanded his vision of both how to combine colors and patterns and how to think about design as part of a project. He started working with 4-harness looms that allow for more complex patterns to be woven without the need for the counting of warp threads or the manipulation of the weft. Through experimentation, he became adept at working with finer yarns and creating cloth that is an appropriate weight for scarves, shawls and other garments. He also developed designs for a laptop bag and other items no one else was making locally. Juan Carlos’ experimentation with natural dyes allows him to use a wide range of rich tones and his experimentation with design has led to a plethora of color combinations, stripes and patterns, thus making his work unique in the village. When he realized that buyers from outside Oaxaca were put off by the texture of the wool available on the local market, he started to seek out yarns made from softer, higher quality wool and has also worked with combinations of wool with alpaca and or silk. At first, he was concerned that the high cost of the raw materials would make these items hard to sell, but he found that he could successfully price the higher quality items to cover his material costs and still pay himself more for his work. The combination of his use of color and design along with the high quality of the materials he is using has placed his work in a category of its own.

Juan Carlos Contreras Sosa, Scarves. Merino, alpaca and silk dyed with Mexican marigold, cochineal and indigo

In addition to workshops on dyes and dye techniques, Juan Carlos participated in a number of workshops on design, which he says expanded his vision of both how to combine colors and patterns and how to think about design as part of a project. He started working with 4-harness looms that allow for more complex patterns to be woven without the need for the counting of warp threads or the manipulation of the weft. Through experimentation, he became adept at working with finer yarns and creating cloth that is an appropriate weight for scarves, shawls and other garments. He also developed designs for a laptop bag and other items no one else was making locally. Juan Carlos’ experimentation with natural dyes allows him to use a wide range of rich tones and his experimentation with design has led to a plethora of color combinations, stripes and patterns, thus making his work unique in the village. When he realized that buyers from outside Oaxaca were put off by the texture of the wool available on the local market, he started to seek out yarns made from softer, higher quality wool and has also worked with combinations of wool with alpaca and or silk. At first, he was concerned that the high cost of the raw materials would make these items hard to sell, but he found that he could successfully price the higher quality items to cover his material costs and still pay himself more for his work. The combination of his use of color and design along with the high quality of the materials he is using has placed his work in a category of its own.

Carlomagno, The Drunks

Carlomagno, The Drunks

Carlomagno, Death’s Cart

Carlomagno Pedro Martinez grew up in a family of potters in San Bartolo Coyotepéc. His parents taught him and his siblings to work with clay when they were quite young. At 18, Carlomagno went to study at the Taller Rufino Tamayo in the city of Oaxaca. The curriculum of the Taller intentionally blurs the boundaries between “art” and “craft” and teaches the students that whatever their medium, they can use their creativity to expand boundaries and express themselves. Once Carlomagno began to conceive of himself as an artist and his work as art, everything changed. He moved away from making the vessels traditionally created by potters in the village and started creating figurative and narrative pieces based on prehispanic myths and legends and local Zapotec culture, often with social and political messages. When he first moved in this direction, some thought Carlomagno was abandoning the tradition, but others recognized that his work, which still used the local clay and traditional methods of working and firing, was simply the latest in many innovations that had already taken place in the village. Carlomagno quickly got the attention of galleries and museums around Mexico and beyond. This led to opportunities for travel to Mexico City, the US and Europe where he saw his work exhibited alongside that of other artists and came to truly accept his role. He says that this travel not only cemented his identity as an artist, but also allowed him exposure to important works of art from many traditions and cultures and from many time periods, thus expanding his vision of what is possible

Carlomagno, Death’s Cart

Carlomagno Pedro Martinez grew up in a family of potters in San Bartolo Coyotepéc. His parents taught him and his siblings to work with clay when they were quite young. At 18, Carlomagno went to study at the Taller Rufino Tamayo in the city of Oaxaca. The curriculum of the Taller intentionally blurs the boundaries between “art” and “craft” and teaches the students that whatever their medium, they can use their creativity to expand boundaries and express themselves. Once Carlomagno began to conceive of himself as an artist and his work as art, everything changed. He moved away from making the vessels traditionally created by potters in the village and started creating figurative and narrative pieces based on prehispanic myths and legends and local Zapotec culture, often with social and political messages. When he first moved in this direction, some thought Carlomagno was abandoning the tradition, but others recognized that his work, which still used the local clay and traditional methods of working and firing, was simply the latest in many innovations that had already taken place in the village. Carlomagno quickly got the attention of galleries and museums around Mexico and beyond. This led to opportunities for travel to Mexico City, the US and Europe where he saw his work exhibited alongside that of other artists and came to truly accept his role. He says that this travel not only cemented his identity as an artist, but also allowed him exposure to important works of art from many traditions and cultures and from many time periods, thus expanding his vision of what is possible

Carlomagno, The Dandy

Carlomagno, The Dandy

Carlomagno, Tribute to my Dog Courage

In addition to pursuing his own career as an artist, Carlomagno has served for many years as director of the Museo Estatal de Arte Popular de Oaxaca (The State Folk Art Museum of Oaxaca.) In his role as museum director, he has organized many exhibits that show the range of work currently coming from the workshops of Oaxaca, the most innovative as well as the most traditional, and has also offered a range of workshops to help local artists and artisans expand their vision, learn new techniques and explore artistic possibilities. In this way, he shares his own expanded vision of what indigenous artists from Oaxaca can attain and supports the development of new generations of artists and craftsmen.

These three examples demonstrate how education can help indigenous artisans to explore options they may not see in their villages and to determine the direction they want to take with their work, based on their own inspiration, desires and values. Education took these artists beyond the limited normative colonial rhetoric that seeks to define and limit what is appropriate for indigenous people to create.

Photo Credits

All photos are by the artists

Carlomagno, Tribute to my Dog Courage

In addition to pursuing his own career as an artist, Carlomagno has served for many years as director of the Museo Estatal de Arte Popular de Oaxaca (The State Folk Art Museum of Oaxaca.) In his role as museum director, he has organized many exhibits that show the range of work currently coming from the workshops of Oaxaca, the most innovative as well as the most traditional, and has also offered a range of workshops to help local artists and artisans expand their vision, learn new techniques and explore artistic possibilities. In this way, he shares his own expanded vision of what indigenous artists from Oaxaca can attain and supports the development of new generations of artists and craftsmen.