JOURNAL ARCHIVE

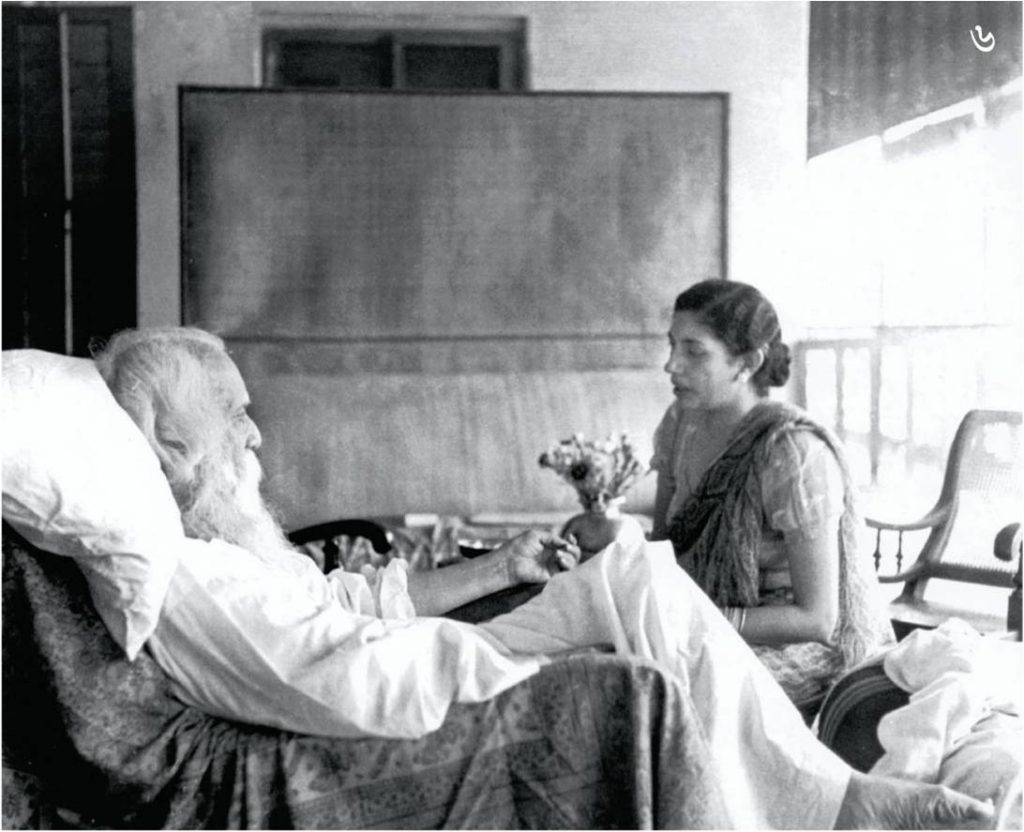

Issue #008, 2021 ISSN: 2581- 9410 Balaposh, a fragrant silk quilt, is an intriguing story of superb craftsmanship. Intriguing because only a single family in Murshidabad (West Bengal, India) know the secrets of the Mughal era Balaposh-making craft. In the 18th century, Murshidabad had reached the zenith of prosperity and was the biggest centre of trade and commerce in north India. The story goes that Nawab Shirajuddin , the heir of Murshed Kuli Khan, found the traditional quilts and wraps, made of animal hair and wool, a bit heavy for Bengal winter. He wanted something different, a quilt which would not be prickly or heavy. It was to be soft as a mother’s lap, warm and comfortable, yet light like a beloved’s embrace and fragrant like a flower! Those were the days of incredible flamboyance and glory. The Mughal love for beauty was still fresh in everyone’s mind. The master craftsman who took up the challenge was one Atir Khan and thus, Balaposh was born. It was expensive and at first, only used by royals and nobles. Even now the craft remains a closely guarded secret of the family of Atir Khan. His great grandson Sakhawat Hossain, who passed away recently, was the only master craftsman. Balaposh is not like kantha, razais or dohars. To appreciate why Balaposh is so special in a country where the art of quilt- making is so very common, we have to understand how it is created. In the last decade of his life, under gentle persuasion of Srimati Sr Ruby Palchowdhuri, Shakawat Hossain agreed to share the secrets of Balaposh-making for the first time, under the aegis of Crafts Council of West Bengal. For a single 6-feet-by-4-feet Balaposh, one needs two lengths of Bangalore or mulberry silk and a special type of cotton, which is lighter than kapas. The cotton fibres are meticulously cleaned and dyed in a dark colour. In a small room, not much larger than the Balaposh itself, the karigar places one length of silk on the floor, taking care that the cloth is secure. He props the other length directly 4 feet above the cloth on the floor. He then starts carding the cotton with his special instrument. The longer he continues, the lighter and fluffier the cotton gets. Soon, it is light enough to float up and then slowly settle on the cloth on the ground. Since the room is tiny, the cotton settles on the cloth and does not scatter. Once that is done, the karigar uses the back of his hand to smoothen the cotton evenly. No lump of cotton should remain. When all the cotton is finally in place, the top cloth is lowered very gently over the cotton fibres. Now, all three layers are stitched tightly. This is the most important skill because if not stitched tightly enough, the cotton layer moves around and gets lumpy. Before completing the sewing, the craftsman slips in tiny attar-soaked muslin pieces in four corners. The end result is a masterpiece of incredibly soft, shimmering, fragrant magic. What sets the Balaposh apart is its fragrant softness, the plain silky surface, with no visible quilting. The beautifully stitched taut borders ensure that the cotton wool layer does not get lumpy or move around even after a century. This Bengal craft deserves the patronage to revive it from dying or being copied/mislabelled by mass marketing imitations. The deliberate conservatism of the artisans has to be overcome and its geographical uniqueness protected and publicised. Fortunately, the last master craftsman has trained his daughter so nurture his family tradition.

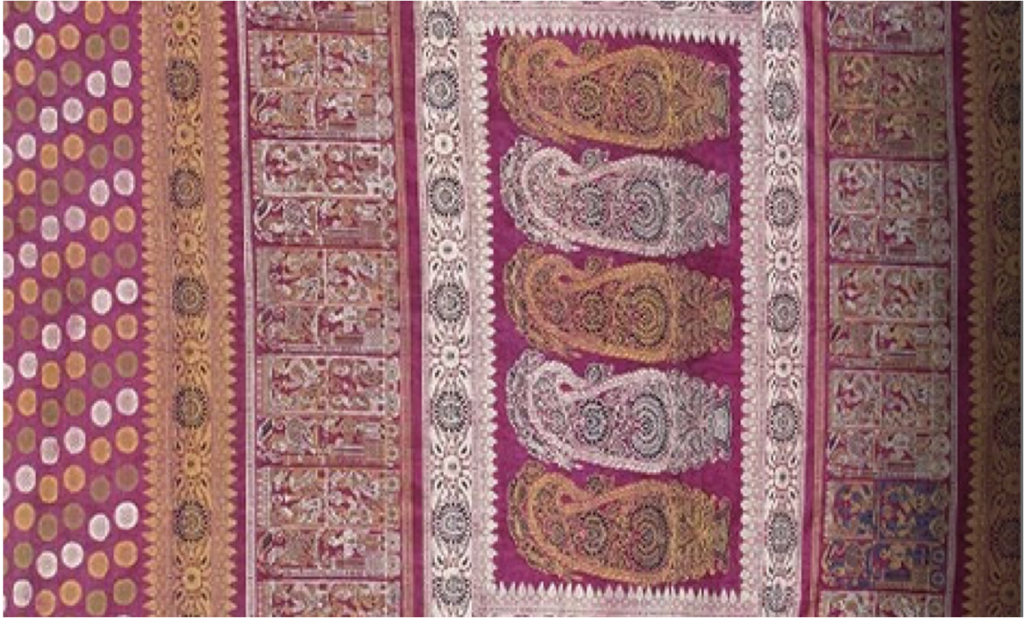

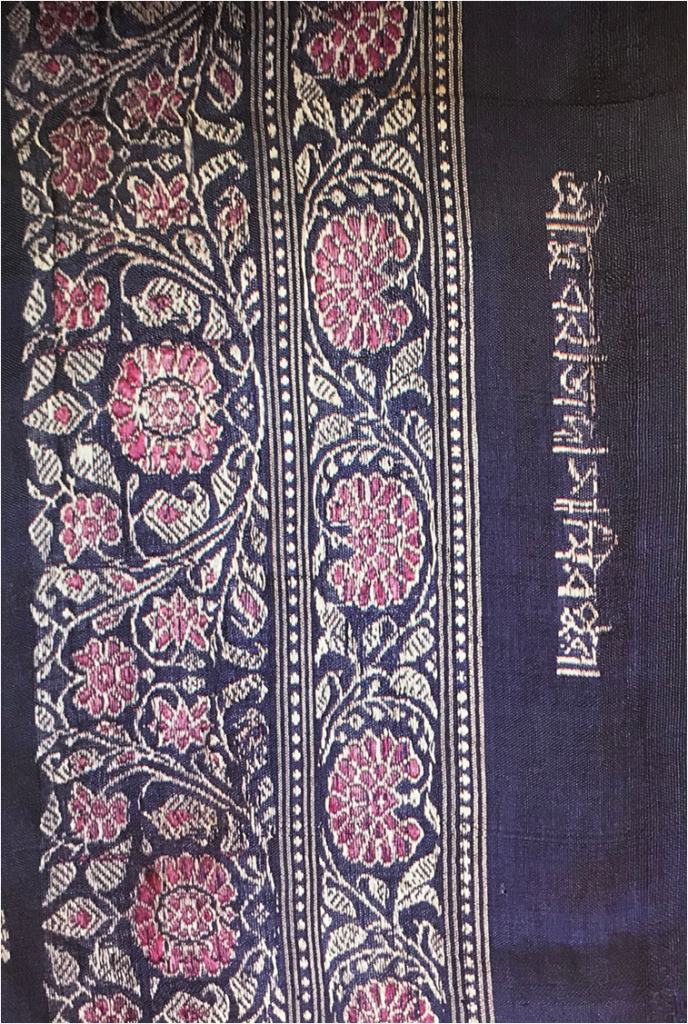

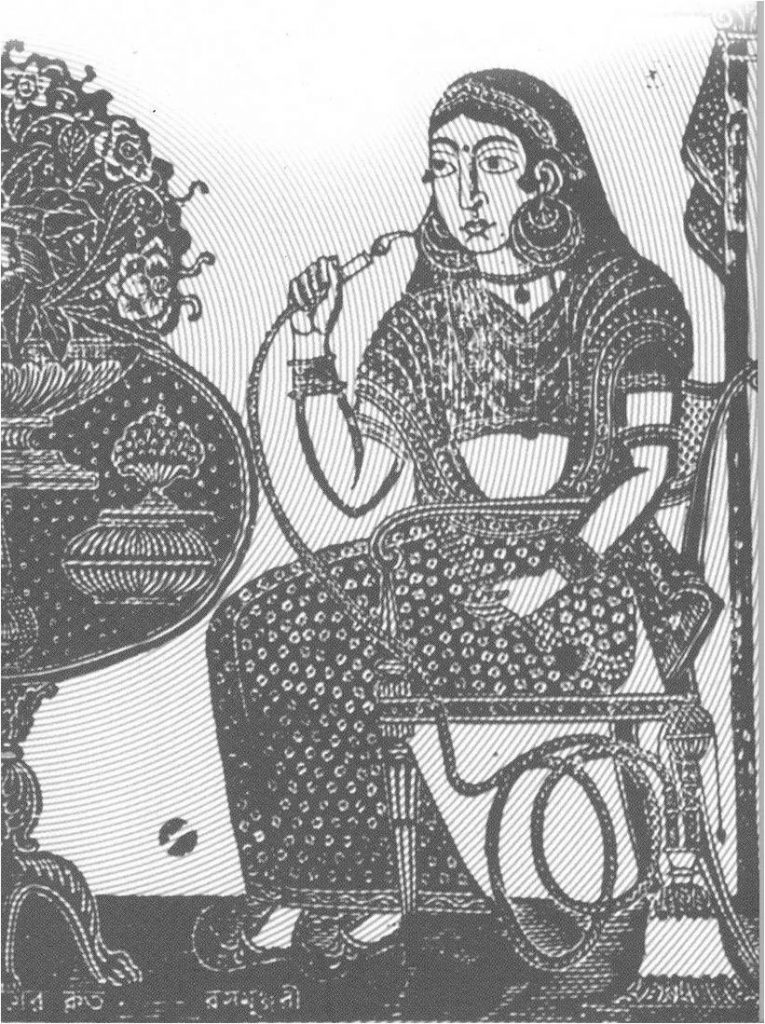

Geographical Background Bishnupur is an earthy town, 110 kilometers from Kolkata and situated in Bankura district. The town is well connected with cities like Kolkata, Durgapur, Burdawan by train and bus. The climate here is hot and dry. Not enough rainfall takes place here during monsoons. Places around Bishnupur are mostly barren and the plateau ofBengal falls in this region. Temperature during summer goes up to 38 degree c, and in winter it drops to 10 deg c`. The town has atleast 12 water resources (Bandh) of different sizes. The colour of the soil is red here, which is very unique to this place. Historical Background Silk is an English word and the synonym of it is Resham which is used in French also. Though researchers say that China was the inventor of silk, but the use of pattavastra (silk) was age old in India. Another name of it is Kousaya which is mentioned by Koutilya in his book ‘ Arthashastra’. In the history of textile in Bengal, Baluchari came much after muslin. Two hundred years ago Baluchari used to be practiced in a small village called Baluchar, situated in Murshidabad district. From the name of the village the sari was named Baluchari. In 18th century, Nawab of Bengal, MurshidKuli Khan shifted his capital from Dhaka to Murshidabad. He was the person who patronized the rich weaving tradition and Baluchari flourished from that time onwards. From its birth period itself Baluchari was the adornment of the elite class. During the period of Delhi-Bengal political intimacy, it was the product of high demand in Mughal court and other royal families of the country. In the middle of the 19th century, elite Bengali house wives used to wear Baluchari. Rabindranath Tagore's brother Abanindranath has written that Maharshi Debendranath's (Tagore's father) wife is wearing Baluchari on the occasion of Maghotsava. The last known weaver of Baluchari was Dubraj Das, who died in 1903. Several saris have been found signed by him. The aspect of signing his name is probably one of the rare instancesof an Indian craftsmen branding his product. But the flourishing was not there for all the time. Because of some political and financial reason Baluchari's of Baluchar village became a dying craft. The village Baluchar drowned in Ganges because of a deadly flood. The fine silk posed a threat to the imported English fabric. The British inflicted punishment on the weavers, thus compelling them to completely give up this profession. Another reason was the dwindling nobility and the lack of patron. The craftsmen were forced to resort to other profession in order to survive. In the first half of 20th century the famous artist Subho Thakur, who was the director of the Regional Design Centre felt it necessary tore-cultivate the rich tradition. Though Bishnupur was always famous for its silk, he invited a master weaver Akshay Kumar Das from Bishnupur to his center to learn the technique of jacquard weaving. Akshay Kumar went back to Bishnupur and worked hard to weave Baluchari on his looms. Bhagwan Das Sarda from the Silk Khadi Mandal helped him with financial and moral support. After a long trial Gora Chand and KhuduBala a weaver couple from Bishnupur finally wove the first Baluchari there, using Akshay Kumar's design.

BISHNUPUR

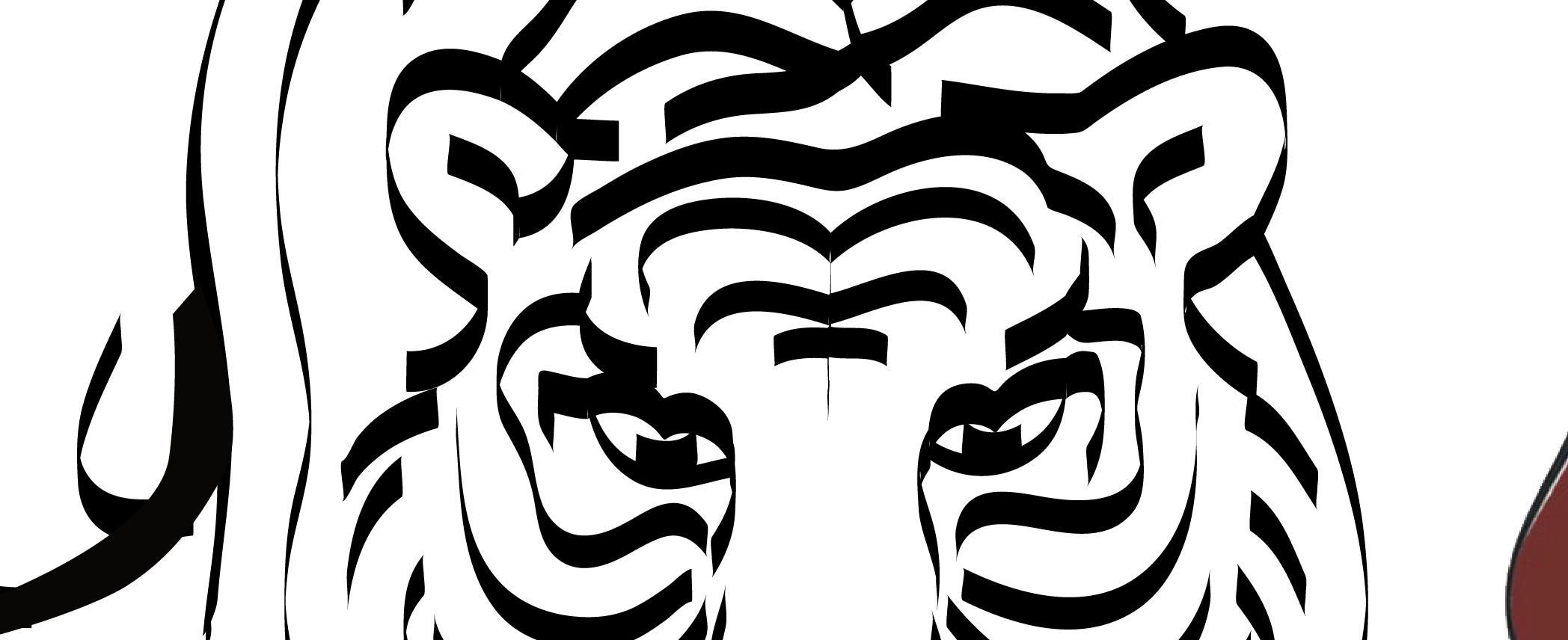

It is said silk, conch and amburi (tobacco) are the specialty of Bishnupuri. Bishnupur was the capital of Malla dynasty. Different kinds of crafts flourished during this period in the patronage of Malla kings. In music also Bishnupur gharana developed during the rule of this dynasty. Temples made of terracotta bricks were another achievement of these rulers. A major influence of these temples can be seen in Baluchar saris. It is common to weave mythological stories on Baluchar, which is often taken from the walls of temples. Bishnupur the tiny town with its rich heritage in handloom, handicrafts and music has gone into oblivion. Patrapara is a dingy alley where even in midnight the rustic sound of jacquard paddle can be heard. This is the place where most of the Baluchari weavers are concentrated. History of Silk The possibility of making cloth from the filament that the silkworm spins into a cocoon was first discovered in China about 2600 BC. Legends tell us that a cocoon accidentally dropped into a cup of tea that a Chinese princess was having in her garden. The hot liquid softened and loosened the fibre, which the princess pulled and drew away from the cocoon as a continuous strand. Another story sites Empress Si-ling-Chi as the first producer of silk fiber. She is venerated as the Goddess of the silk worm. The Chinese who first cultivated the silk worm and developed a silk industry endeavored to keep the source of the raw material secret. Caravans carried silks into the nearest regions where they were traded for 100 years. It is believed that silk was introduced into Europe by Alexander the Great in the fourth century BC. A large silk industry eventually developed in Southern Europe and subsequently spread westward because of the Muslim conquest. Spain begun to produce silk in the 18th century. Italy begun silk production in 12th century and was the leader for 500 years. Production Process The weaving of Baluchari is an intricate process, and requires ample time and labour. A proper and pre-settled division of labour can be seen in this pocket. Previously the system used to weave Baluchari, was called Jala draw-loom system. The silk yarn used in Baluchari was not twisted and therefore had a soft and heavy texture. The usual size of old Baluchari used to be of 447cm(length) 112cm(wide) and count of the thread was 43 warp and the 32 weft. This is the only sari from the Eastern region created on the draw-loom, which contains complicated mechanism for weaving multi warp and multi weft. The ground colour in which the cloth was available, were limited. These pieces are still fresh after hundreds of years. Before modern chemical dyes were introduced, vegetable dyes were used to dye yarn, both silk and cotton, with very fine results. Earlier the technique was very time consuming and expensive. It is said, to complete one sari of Baluchari craftsmen took seven years. The fineness and the class of the earlier versions cannot be replicated. Today, jacquard looms are used to weave the Baluchari sari. The size of modern Baluchari is 558cm (length) &112cm (wide) and the count of the thread is 38 warp and 35 weft. However, people who have seen the Baluchari of yore swear that the current ones are not a patch on the old, in quality and in technique. The Production Process of Baluchari Can Be Divided into Several Parts Cultivation of cocoons. Processing of yarns. Motif making. Weaving. Cultivation of cocoons Since the discovery so many years ago that the fiber, or filament composing the cocoon of the silkworm can be unwound and constructed into a beautiful and durable fabric Silkworms have been bred for the sole purpose of producing raw silk. The production of cocoons for their filament is called Sericulture. Under scientific breeding silk worms may be hatched 3 times a year. Under natural condition breeding occurs only once a year. Life cycle of the cocoon is as follows: The egg which develops into a larva or caterpillar- the silkworm. The silkworm which spins its cocoons for protection, to permit development into the pupa, or chrysalis. The chrysalis, which emerges from the cocoon as the moth. The moth of which the female lays eggs, so continuing the life cycle. Within three days after emerging from the cocoons, the moths mate, the female lays 350 to 400 eggs. Each egg hatches into what is called an ant. It is a larva about 1/8 inch (3mm) in length. The larva requires careful nurturing in a controlled atmosphere for approximately 20 to 32 days. During this period, the tiny worm has a voracious appetite. It is fed five times a day on chopped mulberry leaves. After four changes of skin, or molting, the worm reaches full growth in the form of a smooth greyish white caterpillar. Its interest in food ceases. It shrinks somewhat in size and acquires a pinkish hue, becoming nearly transparent. A constant restless rearing movement of the head indicates that the worm is ready to spin its cocoon. Processing of Yarns Silk yarn is procured from Mysore and the neighboring Maldah district. To make the yarn soft, it is boiled in a solution of soda and soap. Then the yarns are dyed in acid colour, according to the requirement of the sari. After boiling and dyeing, 1 kg of yarn shrinks and reduces to 700gms.The yarn is stretched from both the sides in opposite directions putting same force with both palms. This process is needed to make the yarn crisper. Then the yarn is dried in sunlight for few hours. Dried yarns are fixed on a wooden roller (fandali) and one yarn is made from two yarns. In case of Mysore silk one yarn is made from two yarns because the quality is better. But for the Maldah silk three yarns are needed to make one. The final twisted yarn is rolled on a wooden frame, called Latai. In case of Tussar, first the cocoon (tussar seed) is boiled in plain warm water to make it soft. Then they take out at at least 8 to 10 yarns to twist one final yarn(tussar yarn is very fine). The wooden frame (latai) goes to a person, who fixes up all these frames on a bigger frame, which can consist of atleast 30 to 35 smaller frames. Then he transfers these yarns from latais to another frame according to length of the sari. Simultaneously he can roll yarns for minimum 30 saris. The whole process is called Purni. After this process the yarns are rolled on a wooden rod in a round shape. These round shaped yarn balls comes to another worker, who transfers these yarn balls on a wooden beam. Small beams are called Sisaban and bigger ones are called dhal. Now these beams are ready to be fixed in the loom for weaving. Making of the motifs for pallavs and other part of Baluchari is in itself an intricate process. First a person draws the design on a graph paper. Then he colours it according to the requirement of the sari. Coloured graph paper is sent to a person, who punches the card according to the design. He puts a card (piece board) 6.2/33cm, inside the punched box. The graph consists of several squares. These squares again have 8/8small squares. The card puncher takes every small square, sees its colour and punches the card. He punches the card with a metal rod called tobna. He punches the white square and keep the coloured square flat. Generally in Baluchari only two colours are used, but in intricate ones sometimes more than four colours are used. To make the motif for one sari atleast 7000 cards are needed. After punching is over, these cards are sewed in order and fixed in the jacquard machine. From one set of cards more than one sari can be woven. Cards are punched using a mallet and two punches. The small punch is used for the pattern and the large one is used for locating the holes. There is a metal matrix on a wooden base, on which the card is placed with a second matrix fitting over the top. Each hole in a card represents a lift of a shaft matches a marked square on the weave draft. Weaving After jacquard loom has been introduced, a Baluchari takes five to six days to complete. Two weavers work on it, in shift basis. To tighten the sari from both the side while weaving a metal and wooden clip is attached. It is called Katani. To keep the yarn tight from the other side of the loom, some weight is hanged. This weight consists sand, rolled yarn etc. It is called jak. For the border, yarns pass through a framed net called jalipata. A metal handle is fixed on the one end of the beam, where the finished sari rolls down. This handle is called kheel. After little weaving is over, water is sprinkled on the woven part and polishing is done with an oval shaped tin sheet. This tin sheet is called sana. Time to time wax is put on the yarn to make it more even and slippery. During the weaving of paisley (buti) a small boy is needed to weave the buti, and the main weaver weaves the sari. Design Baluchari as mentioned earlier was the sign of aristocracy, the attire of status. This sari had enjoyed special patronage of the Murshidabad Court since the 17th century. There developed a school of design where stylised form of human and animal figures were integrated with floral and geometric motifs in woven materials. Nawabs and Muslim aristocrats used the material mainly as tapestry. But elite Hindus made it into saris in which the ground scheme of decoration became a very wide pallav, often with a large mango or paisley (buti) motifs at the center, surrounded by smaller rectangles depicting different scenes. The sari borders were narrow and had floral motifs. The whole ground of the sari was covered with small paisley and other floral designs. The interesting feature of earlier Baluchari was stylised bird and animal motifs that were incorporated in the paisley and other decoration. Scenes from the Nawabs' court used to be the previous and older design influence. For example When the British took over Bengal, sahibs and memsahibs appeared, a sahib smoking hukka, and the mem fanning herself. The advent of railways and steamboats was also most interestingly documented on these saris. After little weaving is over, water is sprinkled on the woven part and polishing is done with an oval shaped tin sheet. This tin sheet is called sana. Some of the famous scenes are hunting scene of Nawab, running horse with a rider, warrior with a spear in hand, Nawab smoking hukka, etc. some of the contemporary design used in Baluchari are stories from epics, like Pancha Pandava, Shakuntala, Meerabai, Krishnalila, Madan Mohan, temples of Bishnupur etc. Saris depicting wedding scenes are a delight too. The pallav starts with small rectangles all showing palanquin bearers, seemingly carrying the bride. The next line of panel shows the bride and the groom before the holy fire, the line below it shows the couple facing each other. The main panel at the centre shows the exchange of garlands. This is then followed by the rectangles in the same order as at the beginning of the pallav. The border of the sari has musicians playing songs at the wedding. Other depictions include cavalry. The decoration on the rest of the sari could be tiny bunches of flowers, paisleys. The symbolic use of colour has played a part in Indian life atleast since Vedic times. The Sanskrit word for caste, varna, literally means colour and certain colours are traditionally associated with different castes. These caste colours have been reflected in traditional saris something which is still adhered today, even though it is now much more diluted. In terms of clothings and colours Brahmins were traditionally associated with white, as any form of dying was regarded as impure. Today colour has become a more dominant factor in women's clothing, and white is often only worn on ritual occasions such as special pujas. In eastern region it is never worn during wedding because white is also regarded as the colour of mourning. The colour red was associated with kshatriyas, although today it is commonly worn by brides of all castes during wedding. Red is regarded as the auspicious because it has several emotional, sexual, fertility - related qualities, making it a suitable colour for brides and young married women. The Vaisyas were traditionally associated with the colour green but today it usually has an Islamic connotation. The name for green is often the same for the colour yellow, such as pitambara. The colour yellow is traditionally regarded as the colour of religion and asceticism, as saffron yellow or orange is the colour of Sadhus and other individuals who have relinquished their caste and family to lead a spiritual life. On the first day of hindu wedding ceremony in the eastern region the bride is washed in haldi (turmeric) to ritually purify her, after which she wears a yellow sari. Today yellow is also regarded as the colour to be worn on special occasions. Blue is the colour relegated to the Sudras, and high caste Hindu's avoided this colour because the fermentation process used to create indigo was regarded as ritually impure. Among caste Hindus blue and black were both considered as the inauspicious colours, reflecting sorrow. But in Baluchari the colour blue is widely used since its birth. Today blue is a widely used and worn colour and many older women and widows tend to wear saris with muted tones of blue, black, green rather than the pure white sari.MOTIFS USED IN BALUCHAR SAREES

FLOWERS Various types of floral forms abound in Indian saris. Although the Islamic depiction of flowers is purely decorative, various Hindu saris represented it as a good luck, health and prosperity. Flowers also represent the female principle. In Indo-Aryan language flower additionally refers to aspects of female anatomy. Flowers are also used as fertility symbols also, especially lotus and jasmine. LOTUS One of the most complex and enduring symbol in Baluchar saris, is lotus. It represents spiritual power and authority. It also symbolize the material world in all of its many forms. Indian mythology depicts Vishnu asleep upon the serpent Ananta drifting on the eternal sea of milk, where he dreams the universe into existence, features a lotus blossom issuing from Vishnu's navel, upon which Brahma sits. This is the symbol of the creation of the material universe. Such symbolisms are concepts of fertility and fecundity. Lotus symbolizes prosperity and material wealth. THE KALGA he kalga motif is now very ubiquitous in Indian saris, especially in Baluchar. It is locally known as kalka. It is hard to imagine that the motif is only 250 years old. It evolved from 17th century floral and tree of life design that were created in tapestry woven Mughal textiles. The early designs depicts single plants with large flowers and thin wavy stems, small leaves and roots. In the course of time the design became denser, with more flowers and leaves. The term Kalgahas come from Urdu word qalb which means hook. THE PEACOCK The peacock has several associations that at first glance appear to be unrelated. It depicts immortality, love, courtship, fertility, regal pomp, war and protection. Its traditional significance is probably lost, but nevertheless its depiction and symbolism has a long and complex history. THE FISH Fish are potent fertility symbol in Hindu castes in India, indicating abundance of food, wealth and children as well as the generative power of supernatural. The fish is also an avatar of Vishnu who as the preserver is associated with prosperity and material comforts. THE ELEPHANT The elephant is considered an auspicious animal, traditionally associated with water and fertility, and with royalty and regal power. It also depicts the success of the following year's crop. The sheer physical power of elephant has traditionally been harnessed during war, natural disaster which again have regal associations. THE CONCH The conch shell is both a symbol of Vishnu and Nada Brahma, God in the form of sound. It is one of the eight auspicious symbols, representing temporal power, and conch was used in ancient India as a war bugle. DRAPING A BENGALI SAREE lst Bengali saris are six yards in length which is measured by the distance between the elbow and middle finger tips. If measured by hand, it is twelve times the length from the tips of the fingers to the elbow. This length is usually just enough for three to five folds in the front, for covering the head (ghomta) and for aanchal (pallav) which is about one meter. Bengali women drape their saris from the right hip over the bosom and the left shoulder. Then it covers the head, and from under the right armpits, it is thrown over the left shoulder. The packaging of the Baluchari is a simple process. To pack a sari two persons are needed simultaneously. First the whole sari is rolled down on a round shaped beam. The beam is taken out from the loom and brought it to a open space, where enough sunlight is there. Though water is put during weaving for polishing, enough sunlight is required for drying. After drying two persons start folding the sari stretching it from both the side tightly. A thin metal rod is kept on each fold temporarily to give it a precise fold. A thin starched brown paper is put inside the sari to give the fold a proper shape. The last step is to put the sari inside a thick transparent polythene bag. Quality Quality of the Baluchari sari is taken care of precisely. The quality largely depends on the skill of the weaver. Those who maintain the quality appoint experienced weavers. In contrast those who cannot afford them, employ weavers who are young and less experienced. The quality is checked from the dying of the yarn to the packaging of the sari. Better quality Mysore silk is used for a good order. If even they see there is some problem while packing the sari, they reject it and sell it in cheaper rate. But the rate of rejection is remarkably less for a experienced and reputed Mahajan. Marketing Producers of Baluchari has fixed market in Kolkata and other big cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Bangalore etc. Weavers are always busy meeting this demand. There are people, who come from nearby cities like Durgapur, Kolkata, Burdwan, to buy saris directly from the Mahajans. In this case these customers get it a little cheaper. Here Mahajan plays the role of the middleman, between the weaver and the customer. Weavers participate in different fairs and exhibitions through organisations like West Bengal Handicrafts Development Corporation, Crafts Council of West Bengal, KaruUdyan etc. State government organises yearly handicrafts fair (hastshilp mela) at the state capital, where the craftsmen meet the buyer directly. Distribution The saris are supplied to West Bengal Handicrafts Development Corporation and sold at the government emporium Manjusha. It is also sold at the Government handloom emporium Tantuja, and Tantushree. The products are also sold to private shops which are situated in the big cities and nearby towns.ISSUES

Economics A complete Baluchari sari costs more than Rs. 2,500. The weaver who comes to the Mahajans for work, gets Rs.450 to Rs.500 for one sari. Each sari is completed by two craftsmen, after sharing the wage each of them get Rs.200 to Rs.250 per sari. These weavers can make maximum five saris in a month. It can be noted that this kind of weavers are more in number at Bishnupur. For those who have looms at their own house get approximately Rs.1000 for one sari. They do the dyeing, spinning of the yarn and other small jobs on their own. Education Bishnupur has several higher secondary schools and colleges. All the craftsmen send their progeny to school, and they are keen to teach their children properly before they join the family business. Rate of literacy is remarkably high here. Gender Women in weaver families take equal part in the making of the sari, beside their household work. They do the full processing of yarn which is the most important part of the sari. Some of them weave small materials like shawl, but women do not participate in the weaving of the sari. There is no bias and restriction in girl education. Health During the rolling of tussar thread the worker (mostly women) stretches both the legs in front and roll the thread from cocoon (tussar seed) on the upper level of their thigh. During this process the skin of that particular portion becomes tender and the yarn sometimes cuts through the skin (Tussar threads are sharp). To concentrate on minute designs, only one light hangs on top of the loom. Rest of the loom doesn't get much light. Though major part of the weaving is a precision job, it is strenuous for the eye. Most of the weavers get spectacle after joining this work. Weavers start working after taking early lunch by 10:30 am. When they weave, the beam where the sari rolls down, strikes their stomach. They experience permanent abdominal pain. A weaver has to lift heavy jacquard paddle, which weighs 25kgs. According to them they do not get nutritious food, to lift something so heavy so often. Design Sampling and cataloguing system are not yet in practice here. They do not have proper records of their previous works and designs. Old and traditional designs need to be preserved, there is need of proper efforts to catalogue or sample these designs. If the craftsmen can't do it then external efforts can prove to be veryhelpful. Socio-cultural Issues People involved in Baluchari making, belong to weaver's community. Locally they are called Tanti. Now because of the prosperous future of the craft, lot of people from other community have also started this work. Traditional weavers of this sari have got the title khan. It is said that the title is given to them by local Malla kings. Rich weavers have more than one loom at their workshop. Locally they are called Mahajans. There are two kinds of weavers in Bishnupur. Some of these weavers come to Mahajans to work at their looms. They make the sari in shifts for the Mahajan. All raw material is provided to them by Mahajan. These weavers work for four to five hours at a stretch and they work eight to nine hours in a day. Two weavers work on one sari. These weavers are more in number at Bishnupur. There are other kind of weavers who have looms at their own house. Mahajan provides them all necessary raw materials. They weave the sari for the Mahajan within a certain time period. They fix up a price for the sari with the Mahajan, and the weaver is bound to sell the sari to him. Except the weaving part, there are other processes like processing of yarn, motif making, which is done by other people. They do these jobs as part time basis. The processing of thread is mostly done by women. Development Introduction of Jacquard loom itself is a remarkable development which has taken place in this sector. This mechanical loom has enabled them to produce high quality saris in much lesser time. State government started a scheme of providing loan to poor weavers, and they organize yearly handicrafts fair at the state capital. Weavers participate in important fairs like textile fair, Kamala Mela, through the help of NGO'S like Crafts Council of West Bengal. They participate in fairs at foreign countries like England, Canada etc. Mechanisation of small tools saves their time, e.g. (Mechanisation of yarn rolling machine). Problems Identified At Bishnupur most of the weavers are very poor. Their one and only way of earning is weaving. But the system of work prevailing here is exploitation of poor weavers by rich Mahajans. State and Central Government organizes awards for master craftsmen every year. But surprisingly the award always goes to the middleman who actually makes their work done, not to the poor craftsmen who puts his skill. These poor weavers always live in oblivion without any recognition. State government provides loan for the poor weavers. But the money goes to the wrong pocket most of the time. A co-operative exists here called Baluchari Workers Co-operative. It is the organization of mostly wealthy weavers. All Baluchari workers see no hopes from this Co-operative. In Bishnupur mostly saris are in production. As product diversification they have not yet experimented much, though they possess a rich design vocabulary. These weavers just produce shawls and blouse pieces using same designs of saris. Problem faced by the weavers: lack of space Lack of raw materials Lack of variety in colour shades to try new variations. Lack of transport Lack of official staffs for managements of business transactions Lack of funds to purchase looms. Lack of funds to start a dying section in the village. Promotion The craftsmen do not make many efforts for the promotion for the craft. Government has been putting efforts for their upliftment. They have opened handicrafts marketing centre where they have registered craftsmen's name. They have given them identity card, through which they are invited in fairs and exihibitions organised by State and Central Government. NGO's and cooperatives are also helping these craftsmen to market their products. But because of the lack of awareness and ignorance craftspeople cannot take full advantage of these schemes. There are renowned designers who are using traditional crafts skills in their work. If their attention focuses on to this craft pocket, it will be a major help for the craftsmen. Steps Taken By the Government In West Bengal more than five lakhs families are dependent on the handloom industry, out of every sixty, one man is a handloom man. 500 million fabrics are woven in India , and 270 million meters comes from Bengal alone. The government is endeavoring to bring 60% of these weavers to a cooperative scheme. By the March 1980 statistics, 23.2% (41,200 weavers) have bought under the cooperative scheme in West Bengal. There are 1261 handlooms cooperatives in Bengal of which 813 are active. It is hoped to commence atleast another 550 cooperative societies . India has 23 weavers service center, of which one is in Kolkata. They work for the development of and refinement of handloom designs and to provide the required outputs. Problems of Handloom Sector in Bengal Lack of working capital, Uncertainty of sales, Shortage of raw materials The Government has been spending a considerable amount of money on buying cooperative shares with the objective of strengthening their financial base and to help them to attain qualifications to receive bank loans. After much efforts the Reserve Bank of India has come up with a refinancing scheme for the handloom industry, through which Rs. 3,453.17 lakhs of financial aid was given. Without a well defined marketing channel the weavers will neither get guarantees nor interests for undertaking new productions nor for evolving new designs. The state apex cooperative association and the state handloom and garments rights association has united with them and is taking liabilities incurred for marketing garments of new designs. The cooperative association with the help of its 90 handloom selling centers called Tantuja and Manjusha and the development corporation with their 30 Tantushree shops are selling handloom products both within and outside the state. West Bengal in totally dependent on the Southern states for its supply of hanks in the state as compared to its weaving requirements. Suggestions Generally these craft products have less utilitarian vision, this way the market of the product becomes very limited. New products which meet urban trends and fashions should be produced. The new product range could be shawls, scarves, dupatta etc. The craftsmen are not aware of the changing market trends, thus they end up producing the same stuffs for ages. The craftsmen should be made aware of current market trends so that they can accustom themselves in the present scenario. The products are not tagged, which actually hampers in their promotion. It is important to give an identity to these products, which can be given by tagging them. The tags should have information about the craftsmen and the production. This can be very well used as an effective promotion strategy. The competitive advantage here is the product itself which represents a rich weaving skill. It is very necessary to make the weaver aware of this fact and train him to encash this advantage. Handloom expos at the national level seems to be a potent strategy for the marketing of the handlooms, as no other medium offers the customer such a variety of products from all over India as these expos do. Most expos are immensely successful and hence prove the need for more of these marketing channels for handloom products in the future. Acknowledgment I am sincerely grateful to Ruby Pal Choudhury (Hony. Gen. Secretary, Crafts Council of West Bengal) for equipping me with not only essential contacts but financial support as well on behalf of the council. I am deeply thankful to state award winner Baluchari weaver, Biswanath Khan and his family for their generous hospitality inletting me stay and study the craft at their residence. I also extend my thanks to Meenakshi Singh for her able guidance to complete the document. Lastly I convey my thanks to Anupriya Singh and PrachiPatankar for helping me completing the document.| Bamboo is abundantly grown in the forests of Madhya Pradesh, particularly in the eastern districts of the State. This Central State of the Indian sub-continent had dense forest cover that had been studied by British foresters over two hundred years ago. Traditional communities in Madhya Pradesh have used bamboo for several centuries as a basic resource material for basketry, home building and for agricultural supports. When industrialisation touched Madhya Pradesh the bamboo resources were exploited for the production of paper and rayon in a few large-scale mills set up near the forest tracts. Bamboo is treated as a minor forest product and is managed and monitored by the forest departments of the Government of Madhya Pradesh. One species dominates the forest tracts of Madhya Pradesh and this is Dendrocalamus strictus, which grows in the rain fed forest tracts in abundant quantities. The forest working plans for each district takes care of management and utilisation of these bamboo resources. State and National laws govern the extraction and movement of these bamboo resources within and outside the State. The local communities of bamboo workers called Basods are given special privileges in the use of the local resource through legal dispensation that is monitored by the forest departments at the district level. The Basods make their livelihood from the conversion of the bamboo resources into baskets for local and up-market uses and their relationship with the forest resource is a tenuous one. Another species of bamboo that is found in the forest is Bambusa bambos (Bambusa arundinacae), which is planted by the foresters in rain fed gullies and near streams. This species is also planted as homestead bamboo plantations near homes and farms of local settlers since it is a useful species for basketry and housing needs. In spite of this abundance of bamboo resources and other natural resources the State of Madhya Pradesh is seen as a backward one in development terms. There is much rural poverty and the financial resources of the state are quite strained in meeting the very basic infrastructure needs of its people in the rural areas are deprived of visible signs of sustained development. Is it possible to change this state of affairs that seems to have been perpetuated for so long without the introduction of very heavy capital flows from outside to induce growth and prosperity in the region? We now believe that it is possible to bring about dramatic change in the local condition through an integrated set of measures and actions by both government and local residents alike along with a well-developed master plan for the sustainable use of the potential of the bamboo resources of the State. The potential of bamboo as an economic driver has been demonstrated in many ways in recent years by field success in China and a few East Asian countries. The growth of new industries based on local bamboo resources has been an eye opener for many people and the lessons that this holds for a State like Madhya Pradesh is a source of hope and conviction that could influence decisions at the macro and micro economic levels alike. While the State Government can mobilise policy change and provide the necessary supports and incentives for the growth of an economic region based on bamboo, the local people, both farmers and entrepreneurs, could make the efforts to coordinate their moves to be in sync with new opportunities that can unfold from investments in innovation and subsequent investment supports in a synchronised manner. New Models for Growth For such a coordinated set of actions and commitments to take off we will need to change entrenched mind-sets about bamboo, which is a very old material in the region. It is here that innovation and training will need to play a critical role in first creating sufficient evidence of potential new applications and value generation which is followed by a sustained programme of capacity building in terms of human resources that are required to exploit this potential with the new knowledge resources that are available today. One major policy thrust that is critical for the bamboo sector to grow in the State is the shift in focus from forest based bamboo resources to farm based supplies, which do not exist today, in any significant volume. The new applications that provide value added possibilities require bamboo that is consistent in quality and this can only be provided by plant stocks that are intensively managed so that the desired quality is selectively bred into the crop by good practices that are embedded into the cultivation and harvesting of the natural resource. This may increase the base cost of the bamboo itself but it will also increase employment at the farm level, which will be a welcome source of revenue for local people in the State particularly in the rural areas. Better quality of bamboo thus produced can be used for numerous value added applications through a programme of sustained innovation and design which could be the focus of the micro enterprises that could be established on the basis of such availability of new bamboo resources locally. Such micro industries could support very large employment with very little capital outlays and can be the mainstay of the local cluster that is based on the bamboo resource. These micro industries could produce a vast range of low technology intensive products for local consumption as well as finished goods for up-markets in the district headquarters and major towns of the region. The product categories that could be sustained in this value added market are furniture for local housing, toys and children’s furniture, agricultural implements and garden structures such as local green houses for value added agriculture, housing components and kitchen accessories and baskets that are traditional and still in demand. It should not be mistaken that this is a call for a return to some old or traditional situation based on the historic uses that bamboo was used in the past, nor are we seeking the return of the “good old days” that we Indians talk about our glorious civilisation of 5000 years vintage. The call is for investments into modern innovations that are needed and implicated in rural India if the rural producers and users can get social and economic equity in employment, and economic growth in an increasingly globalised world economy. Besides these micro enterprises that are small family or small group ventures we can anticipate the establishment of viable small and medium enterprises if funds are made available with adequate incentives from the Government to exploit another class of semi-industrial products which too are high in employment generation potential and which have local uses as substitutes for many potential imports from urban based industries. These applications include processed bamboo components using simple machine tools arranged into small and medium sized industrial units that are both viable and able to produce goods for the local and up-market needs in a competitive manner. These machines and power tools that can help transform the local economy too need to be innovated and developed, each offering an interesting new avenue for value added product creation and for the creation of quality labour opportunities that are not based on human drudgery alone. Bamboo used as splits, rods, sticks, rounds, squares and shavings or fibres can all be used to make commercial products such as matchsticks, agarbatti sticks, agricultural props and poles for fruit orchards. However for the strategy to fructify the early stages of conversion must be mechanised through the creation of small and effective machine tools that can be both managed and maintained in the rural setting even if they are not produced in the region. The advantages of globalisation can be leveraged here by helping the local craftsman obtain the best possible tools from across the world if these are carefully selected and made available locally so that their livelihood is protected and developed in balanced manner. Bamboo can be converted and explored in other ways as well. Bamboo culms that are solid or with very small lumens as seen in some species could be further extended to the production of panel boards using splits and squared rods, which will find application in the production of furniture and local housing. Simple composite and lamination technology can be adopted to make a wide range of boards and members for many new applications in the domestic, industrial and retail space which could be a very effective timber substitute in the years ahead. The fibreboards that are possible from bamboo can be used for a great many applications and here the large resource found in the forest can be used to achieve high quality results. All this will only be possible if and only if the products made from these new enterprises find market acceptance both locally and in up-market applications. This is where the need for sustained investments in design are implicated to help local entrepreneurs move forward with well designed and tested solutions which are both innovative thereby providing additional value when compared to the traditional applications that have been used so far. Further, when we advocate new farm based cultivation models for the State we need to look at the needs of the farmers closely from the experience at other places. Farm Based Economic Model We anticipate at least three types of farm production based on scale of operation, all of which are simultaneously viable in the region since they can cater to different downstream user groups in a sustainable manner. The micro enterprises may well be based on own farms that are homestead based with little excess production available for distribution. However the fact that these enterprises have a sustainable supply of good quality raw material under their control they are better equipped to face competition and price fluctuations in the market place. The second scale of farm could be in the form of small and medium sized farms managed by local farmers that produce the quality of materials required by the local small industries, some owned by the farming families and others by partner cooperatives in nearby areas. The third scale of farm production could be in the form of large corporate farms that could be set up to meet the needs of large scale users in various industry segments and for the open market for particular quality bamboo materials. Here we anticipate the cultivation of a number of other species based on demand both local and up-market. Such a cluster of farm based bamboo production and utilisation can be envisaged and supported by Government policy and banking supports which would lead to a sustained economic growth that is based on one of the fastest growing plant resource known to mankind. This will only be successful if the products of the industries can fetch a better value for the producers and create a brand value in the minds of the users that is both satisfying and acceptable. Bamboo has many useful parts and the farm-based strategy must look at the real possibility of full biomass utilisation as a strategic goal of the proposed programme. While each part may have multiple uses each such use should be evaluated in the context of the total value that any particular pattern could generate for the farmer, the local population, the environment and the down-stream craftsmen, entrepreneurs and the markets as a whole. For instance bamboo leaves could be a very good source of fibre for the production of fibreboards and even handmade paper. However this use if exploited fully would deprive the soil of certain natural nutrients, which would otherwise be available. Bamboo shoots can be extracted from most species as a source of human food or animal feed. Some species are preferred for shoot extraction but in most cases selective extraction of shoots makes the clump grow more robust and provide healthier culms. Therefore a balanced utilisation model at the farm level may call for such discriminated multiple uses that could maximise the benefits that would accrue to the producers and the environment alike. It is here that a sustained programme of local research that is based on these new farms would need to be undertaken in local institutions and in collaboration with local producers and users. The leaves of the bamboo plant, the culm sheaths, its rhizomes and branches are all valuable raw materials that could be the subject of future studies and design strategies. Such an approach makes sense in a farm based model since the seasonal nature of culm harvesting could be spaced out with periods of other activities that are based on the different parts of the bamboo plant which would help create off seasonal rural labour which can have a positive effect on the local economy. The farmers being in control of these varied uses can plan according to the viability of each option and achieve excellent results on the whole. Research and design can indeed provide such solutions if adequate investments are made towards innovations in this sector which can then be owned and used by the local producers from a common pool of knowledge that is generated by local institutions. This kind of innovation and dissemination will help create sustainable industries that could be set up with very limited induction of capital from external sources. Local labour and enterprise can be directed and coordinated by policy initiatives of Government to grow what could be best described as an agro-industrial district cluster based on bamboo. This bamboo district cluster model would support many scales of farming as well as many scales of production, each with their own sets of products and services. The setting up of this district cluster would create multitude of opportunities for the offer of services that are needed in any such industrial cluster. Communication, transport, food, accounting, skilled labour and educational and training infrastructure could be planned and catalysed with local participation. Power is one of the critical needs for such an agro-industrial district cluster but here again bamboo could be used from the forest to produce local power using gasification as a method at fairly reasonable levels of local investment if central power supply is likely to be delayed or found unviable. This kind of localised growth could create islands of prosperity in a very short time even in the remote districts that have unreliable power supply as of now. This kind of localised power supply opens up new possibilities for the exploitation of the bamboo resources of the forest areas. Government policy is needed here to regulate the use of forest-based bamboo to ensure sustainable extraction and use. Here we see the possibility of two initiatives for policy that could benefit the local population and the environment alike. The degraded forest areas need government supports to make the joint forest management schemes to work better. Greater ownership for the local population is one such initiative that needs to be explored. The active forest areas that are not within the conservation zone too needs to be brought under the JFM schemes on a long term basis to ensure sustainability of the forests while extraction of bamboo and other forest produce continues on a regulated basis. The other zone that is the core conservation zone will need another set of guidelines and a regulatory framework that involves locals as well as Government representatives in coordinated teams. Human Resource Development Madhya Pradesh has also stayed backward due to poor infrastructure and low productivity of its rural populations due to low levels of education and poor access to finance and other resources and infrastructure. This needs to be changed and the bamboo initiative can give a focus to the kind of education and training that is imparted to the local human resources. New local institutions and processes may be needed that could help develop the required knowledge and innovation resources in a continuing and sustained manner. Knowledge about cultivation and management of farm based bamboo resources will improve productivity and this will help the local population to exploit the incentives that are on offer as part of the overarching development strategy of the Government of Madhya Pradesh. Further, skill development and training that is focussed on the introduction of new and improved products and processes will set the local producers on a growth path of better productive use of their human skills and natural resources of bamboo. Better quality of farm based bamboo and better products from the planned clusters will create a new and valuable brand for the bamboo initiative that will have a ripple effect that has far reaching implications for the sustained growth of the local economy. With the possibility of multiple centres or clusters growing up and being located in at least ten eastern districts of Madhya Pradesh, will be a power house of innovation and change that can transform the economic landscape of the whole State. Bamboo is projected to become a major industry across India with the efforts of the Planning Commission and the Central Governments Mission approach. The State of Madhya Pradesh is very well positioned to share the resources being disseminated by the various Central schemes through its own progressive policies and initiatives that are already under way. If there is so much potential, why then is the situation still bleak for the rural producers of Madhya Pradesh? Why is the demand for industrial uses of bamboo tapering off from the paper mils and rayon mills located near the region? Why are the forest depots getting such a low return for the stocks lying with them? The answer to these questions perhaps lies in the lack of innovation in this industry and this could be changed with some policy and investment initiatives that can change local perceptions and also create real new opportunities where none seemed to exist in the past. This is an ideal setting to demonstrate the power of design at the strategic level. Innovation and Design The locally abundant species of bamboo, Dendrocalamus strictus has not so far fetched a premium in any market. In fact the traditional users are also finding substitutes for this material. Paper producers are now using agricultural residues and imported wood pulp as their main source while pressing for reduction in the price of bamboo supplied by the forest department. Such natural pressures for change and obsolescence take place everyday in all sorts of industries. It is here that some of these industries have realised the power that active innovation and design can play in making viable new schemes when old models start to fade. At NID we explored the possible applications of D.strictus through a number of creative and innovative exercises to discover a real potential, which may only be the tip of the iceberg. With the assistance and sustained support of the Development Commissioner of Handicrafts, Government of India, the NID team was able to carry out experimental design investigations on a few popular bamboo species with an aim of discovering and developing products suitable for rural production. While in the past many of these explorations looked at product diversification in the traditional handicrafts sector in the recent efforts a greater emphasis was placed on products for rural use. While export markets helped spawn a cash rich economy it is a very sophisticated operation that can be mastered only if a very high degree of entrepreneurship exists in the region along with high quality of trained human resources. In many remote rural situations these conditions are hard to find and the result is that such products need not contribute to the local economy since the value added is located at the market end and not in the hands of the producer. It is in such a situation that the focus on products for local use and in nearby markets would create innovations that can create new market opportunities in the rural hinterland for the local producers. At a meeting called by the UNDP in Delhi I had called this strategy as innovations at the “thick end of the wedge”. Low technology innovations that can be used and exploited by rural farmers and producers can be as forward-looking and critical for economic growth as the so-called “cutting edge” innovations that are being achieved by our hi-tech industries and the software sectors. Rural users and producers need such innovations desperately to change their condition for the better, with a little help from Government policy and infrastructure that facilitates sustained innovation that can move many pressing needs towards viable solutions that can be locally implemented. Gandhijis strategy of Khadi needs to be given new meaning through such initiatives by using advanced knowledge resources available to us in a sustained programme of research and design to create solutions that can generate rural prosperity and economic growth across that region. Bamboo has this inherent capability if used in conjunction with high quality innovation and good business models to bring about dramatic change in our village economy. It is indeed a seedling that can spread wealth, and we need to take these moves forward in a determined and systematic manner. Sustained investment in an institutional and industrial setting will show many new and exciting applications that will help keep the industry viable and profitable in the years ahead. The properties of the local bamboo needs to be continuously explored and the findings must be fed back into training programmes for local craftsmen and farmers so that these are assimilated into the local knowledge which will be at the centre of the value addition strategy of the proposed local district clusters. Such a knowledge rich approach will provide a stable demand for the produce of the region and help it compete with other species and materials occupying the product landscape of an active market economy that India is heading towards. Promoting the local innovations and protecting it through brand building and exposure to markets across India would fall on Government promotional agencies working in concert with the associations of local producers. Such an integrated development model can be sustained since bamboo is such a versatile material and the social and political hope and economic value that the proposed process can unfold and release will make it a major economic driver of the State economy if carefully managed and implemented as an integrated multi-layered strategy. References Charles and Ray Eames, The India Report, Government of India, New Delhi, 1958, reprint, National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, 1997 Victor Papanek, Design for the Real World, Thames & Hudson Ltd., London, 1972 Stafford Beer, Platform for Change, John Wiley & Sons, London, 1975 V S Naipaul, India: A wounded Civilization, Penguin Books Ltd., Harmondsworth, Middlesex, 1979 M P Ranjan, Nilam Iyer & Ghanshyam Pandya, Bamboo and Cane Crafts of Northeast India, Development Commissioner of Handicrafts, New Delhi, 1986 Tom Peters, Liberation Management: Necessary Disorganization for the nanosecond Nineties, Pan Books, London, 1993 J A Panchal and M P Ranjan, “Institute of Crafts: Feasibility Report and Proposal for the Rajasthan Small Industries Corporation”, National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad 1994 M P Ranjan, “Design Education at the Turn of the Century: Its Futures and Options”, a paper presented at ‘Design Odyssey 2010’ design symposium, Industrial Design Centre, Bombay 1994 National Institute of Design, “35 years of Design Service: Highlights – A greeting card cum poster”, NID, Ahmedabad, 1998 M P Ranjan, “The Levels of Design Intervention in a Complex Global Scenario”, Paper prepared for presentation at the Graphica 98 - II International Congress of Graphics Engineering in Arts and Design and the 13th National Symposium on Descriptive Geometry and Technical Design, Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil, September 1998. S Balaram, Thinking Design, National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, 1998 M P Ranjan, “Design Before Technology: The Emerging Imperative”, Paper presented at the Asia Pacific Design Conference ‘99 in Osaka, Japan Design Foundation and Japan External Trade Organisation, Osaka, 1999 M P Ranjan, “From the Land to the People: Bamboo as a sustainable human development resource”, A development initiative of the UNDP and Government of India, National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, 1999 M P Ranjan, “Rethinking Bamboo in 2000 AD”, a GTZ-INBAR conference paper reprint, National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, 2000 M P Ranjan, Yrjo Weiherheimo, Yanta H Lam, Haruhiko Ito & G Upadhayaya, “Bamboo Boards and Beyond: Bamboo as the sustainable, eco-friendly industrial material of the future”, (CD-ROM) UNDP-APCTT, New Delhi and National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, 2001 M P Ranjan, “Beyond Grassroots: Bamboo as Seedlings of Wealth” (CD-ROM) BCDI, Agartala & NID, Ahmedabad, National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, 2003M P Ranjan, “Feasibility Report: Bamboo & Cane Development Institute, Agartala”, UNDP & C(H), and National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, 2001 Tom Kelley & Jonathan Littman, The Art of Innovation: Lessons in creativity from IDEO, America’s leading design firm, Doubleday Books, New York, 2001 Vidya Viswanathan & Gina Singh, “Design makes an Impression: Indian Industrial Design gets ready to hit the big time…”, in Businessworld, New Delhi, 22 January 2001 pp. 20 – 31 K Sunil Thomas, “Better By Design: India finds itself at the crossroads of a revolution…”, in The Week, Kochi, 23 September 2001 pp. 48 – 52 Charles Wheelan, “Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science”, W.W.Norton & Company, New York, 2002 Amartya Sen, “Employment, Technology & Development”, Oxford University Press, (Indian Edition), New Delhi, 2001 Surjit S. Bhalla, “Imagine There is no Country: Poverty, Inequality and Growth in an Era of Globalisation”, Penguin Books, New Delhi, 2003 Planning Commission, Government of India, “National Mission on Bamboo Technology and Trade Development”, Planning Commission, Government of India, New Delhi 2003 Enrique Martinez & Marco Steinberg, Eds. Material Legacies: Bamboo”, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, 2000M K Gandhi, Khadi (Hand-Spun Cloth) Why and How, Navjivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, 1955 Paper prepared for publication in the pre-conference souvenir for the World Bamboo Congress, New Delhi from 27tn February to 4th March 2004. |

Issue #10, 2023 ISSN: 2581- 9410 I (Shama Pawar) came to Hampi in 1997 as a young artist and little did I know that Anegundi - Hampi would be my life’s work. Even on my first visit I enquired if there was a village, a living settlement within the site. It was then that I was directed to Anegundi, a historical settlement that predates the Vijayanagara Hampi. Located on the banks of the Thungabhadra this region has been known as a pilgrimage place ever since the 6CE. The Chalukyan inscriptions call it Pampakshetra. In the 14th Century the Vijayanagara Capital was established in Hampi and the rest is history. My work has little to do with history. I certainly use it as an inspiration and certainly think of it as a Heritage Resource. The word “Heritage” though has a different connotation for me. It is not limited to just architecture or other conventional aspects be it intangible or tangible. For me Heritage is everything that shapes our being. Everything from nature, culture, irrigation systems, agriculture. These are the aspects that have influenced the living culture of the World Heritage Site of Hampi.

Anegundi View from Elepahant stable

64 pillar matapa

I would like to point that the work that I have done through The Kishkinda Trust and as convenor for INTACH does not limit itself to craft. We call the model “Rural Development in a Heritage setting”. All the projects that we undertake look at holistic model. In 1999 when the cottage industry was set up there was a need to attract tourists to the area and therefore we made responsible tourism as one of our initiatives. To ensure that there is a positive impact of visitors coming to the village we started the Solid Waste Management Program. Finally, to ensure that the future generation sees has broader horizons than just engaging in agriculture we started an Education through performing arts program.

Banana Fibre is not a traditional material used in the area; it is something that we as The Kishkinda Trust introduced in 1999.

Why Banana Fibre? It has to do with a Vijayanagara Era Irrigation system that is still in use in the area that allows for flood irrigation and the growth of Banana plantations. This was going to be a resource that was going to be available for many years to come unless the ecology of the place completely changes.

There are 2 types of banana fibres available namely extracted and un extracted.

Extracted Banana Fibre involves mechanical as well as automated mechanical extraction technique.

Available only once in a year after Banana Harvest. It requires Machinery for Extraction. Requires ample storage space as extraction happens only once a year. Harvest has to be done on a large scale and requires heavy vehicles for transport.

Unextracted Banana Fibre

At TKT we use the unextracted banana fibre which is quite coarse and its usage is limited to lifestyle accessories only due to its tensile strength and textural properties. Available through the year barring the months of Monsoon. Requires no machinery for extraction. This is a waste product for the farmer. Can be stored by artisans at their homes as the material is available through the year. Harvest can be done by individual artisans and require the simplest agricultural tools. Transport is easy as the material is quite light.

Banana Fibre is not a traditional material used in the area; it is something that we as The Kishkinda Trust introduced in 1999.

Why Banana Fibre? It has to do with a Vijayanagara Era Irrigation system that is still in use in the area that allows for flood irrigation and the growth of Banana plantations. This was going to be a resource that was going to be available for many years to come unless the ecology of the place completely changes.

There are 2 types of banana fibres available namely extracted and un extracted.

Extracted Banana Fibre involves mechanical as well as automated mechanical extraction technique.

Available only once in a year after Banana Harvest. It requires Machinery for Extraction. Requires ample storage space as extraction happens only once a year. Harvest has to be done on a large scale and requires heavy vehicles for transport.

Unextracted Banana Fibre

At TKT we use the unextracted banana fibre which is quite coarse and its usage is limited to lifestyle accessories only due to its tensile strength and textural properties. Available through the year barring the months of Monsoon. Requires no machinery for extraction. This is a waste product for the farmer. Can be stored by artisans at their homes as the material is available through the year. Harvest can be done by individual artisans and require the simplest agricultural tools. Transport is easy as the material is quite light.

What started off as an experiment with a Handful of women; today Banana fibre has become the craft identity of the area. I am a firm believer that creative energy such as craft should not be curtailed. Most crafts are a great example of how techniques and crafts only grow when they are not limited to geography, a particular community etc. The Kishkinda Trust has trained more than 1000 individuals in the Hampi region in different skills. Our goal is to set up the cottage industry and hand it over to the community to run the same. We have achieved the same with Banana Fibre to a certain extent and are taking strides towards each artisan becoming an entrepreneur in their own right and be completely independent of The Kishkinda Trust.

What started off as an experiment with a Handful of women; today Banana fibre has become the craft identity of the area. I am a firm believer that creative energy such as craft should not be curtailed. Most crafts are a great example of how techniques and crafts only grow when they are not limited to geography, a particular community etc. The Kishkinda Trust has trained more than 1000 individuals in the Hampi region in different skills. Our goal is to set up the cottage industry and hand it over to the community to run the same. We have achieved the same with Banana Fibre to a certain extent and are taking strides towards each artisan becoming an entrepreneur in their own right and be completely independent of The Kishkinda Trust.

There are benefits and challenges to working with new materials, techniques or technologies. The challenges are certainly endless but are some benefits. Since we are a non-traditional cottage industry we are not bound by what we do and how we do it. The artisans have gotten used to experimenting be it materials or techniques. Since this is a contemporary craft it has always looked at products from a contemporary lens. Also, material availability has always pushed us towards using whatever resources are available in our vicinity and not look too far for the same.

There are benefits and challenges to working with new materials, techniques or technologies. The challenges are certainly endless but are some benefits. Since we are a non-traditional cottage industry we are not bound by what we do and how we do it. The artisans have gotten used to experimenting be it materials or techniques. Since this is a contemporary craft it has always looked at products from a contemporary lens. Also, material availability has always pushed us towards using whatever resources are available in our vicinity and not look too far for the same.

In 2017 the area was faced with a major Water Hyacinth problem. The water bodies were completely choked up by this invasive weed. Water Hyacinth is an environmental hazard that covers up water bodies cutting off access to Sunlight and thus causing problems to sous-marine ecosystems due to depleting oxygen levels. We looked at an ecological problem as a solution for livelihood through crafts.

We are hoping that we are able to benefit from the MGNREGA scheme which harvests the water hyacinth from water bodies. This would make it possible for us to train more individuals and start a new cluster of Artisans working with Water Hyacinth. We truly believe that water hyacinth could be used in an innovative way that go beyond craft.

In 2017 the area was faced with a major Water Hyacinth problem. The water bodies were completely choked up by this invasive weed. Water Hyacinth is an environmental hazard that covers up water bodies cutting off access to Sunlight and thus causing problems to sous-marine ecosystems due to depleting oxygen levels. We looked at an ecological problem as a solution for livelihood through crafts.

We are hoping that we are able to benefit from the MGNREGA scheme which harvests the water hyacinth from water bodies. This would make it possible for us to train more individuals and start a new cluster of Artisans working with Water Hyacinth. We truly believe that water hyacinth could be used in an innovative way that go beyond craft.

Moving towards securing futures

We at TKT look at securing futures for communities in our region by investing in energies in creating Heritage Resources like natural fibre. What we mean by creating Heritage resources is growing trees to create infrastructure and add value to the produce that one can obtain from them. Also change the way we look at agriculture, look at the market needs and respond to the change in an informed manner. In this endeavour we have recently signed an MOU with Karnataka State Rural Development and Panchayati Raj University, Gadag. We hope that partnerships such as these will help us achieve the model of Rural Development in a Heritage Setting.

When it comes to existing cottage industries, we do understand the need to move on with times and the need for a craft to evolve. Up until now Banana Fibre rope that is used as the raw material has been completely handmade. We are cognizant that in the years to come the number of people who wish to make handmade rope might decline. We have already started researching how it is possible to make high quality machine made rope. This advancement will help keep the craft alive.

There is a need for an ecosophical way of life in places that have never before experienced such a large influx of visitors. The key is to change the approach at the onset which is able to put dynamic systems in place.

Moving towards securing futures

We at TKT look at securing futures for communities in our region by investing in energies in creating Heritage Resources like natural fibre. What we mean by creating Heritage resources is growing trees to create infrastructure and add value to the produce that one can obtain from them. Also change the way we look at agriculture, look at the market needs and respond to the change in an informed manner. In this endeavour we have recently signed an MOU with Karnataka State Rural Development and Panchayati Raj University, Gadag. We hope that partnerships such as these will help us achieve the model of Rural Development in a Heritage Setting.

When it comes to existing cottage industries, we do understand the need to move on with times and the need for a craft to evolve. Up until now Banana Fibre rope that is used as the raw material has been completely handmade. We are cognizant that in the years to come the number of people who wish to make handmade rope might decline. We have already started researching how it is possible to make high quality machine made rope. This advancement will help keep the craft alive.

There is a need for an ecosophical way of life in places that have never before experienced such a large influx of visitors. The key is to change the approach at the onset which is able to put dynamic systems in place.

| Introduction The art of Bandhani is highly skilled process. The technique involves dyeing a fabric which is tied tightly with a thread at several points , thus producing a variety of patterns like Lehriya, Mothda, Ekdali and Shikari depending on the manner in which the cloth was tied. |

| History Different forms of tie and dye have been practiced in India. Indian Bandhani, a traditional form of tie and dye, began about 5000 years ago. Also known as Bandhni and Bandhej, it is the oldest tie and dye tradition still in practice. Dyes date back to antiquity when primitive societies discovered that colours could be extracted from various plants, flowers, leaves, bark, etc., which were applied to cloth and other fabrics. Even though color was applied they didn't consider this dyeing. It was simply a form of embellishment. What was considered dyeing was the art of using color to form a permanent bond with fiber in a prepared dye bath. Ancient artists discovered that some dyes dissolved and gave their color readily to water, forming a solution which was easily absorbed by the fabric. Herbs and plants like turmeric and indigo were crushed to a fine powder and dissolved in water so that cotton material could be dyed in deep colours. These colours have been used in India since ancient times and are considered to be the origin of the art of dyeing. Throughout Asia, India and the Far East, traders packed tie and dye cloths as part of their merchandise.It is difficult to trace the origins of this craft to any particular area. According to some references it first developed in Jaipur in the form of Leheriya. But it is also widely believed that it was brought to Kutch from Sindh by Muslim Khatris who are still the largest community involved in the craft.Bandhani was introduced in Jamnagar when the city was founded 400 years ago. Bandhani fabrics reign superme in Rajasthan and Gujarat which are home to an astounding variety of traditional crafts. Century-old skills continue to produce some of the most artistic and exciting wares in these two states and are popular all over the world. Rajasthan is a land of vibrant colors. These colors are a striking part of the life there and are found in the bustling bazaars, in fairs and festivals, in the costumes worn and in the traditional paintings and murals. |

| Regions The art of Bandhani is practiced widely in Rajasthan, with Barmer, Jaipur, Sikar, Jodhpur, Pali, Udaipur, Nathdwara and Bikaner being the main centers. Bandhani comes in a variety of designs, colors and motifs and these variations are region-specific. Each district has its own distinct method of Bandhini which makes the pattern recognizable and gives it a different name.The centers of tie and dye fabrics in Gujarat are Jamnagar in Saurashtra (the water in this area brings out the brightest red while dyeing) and Ahmedabad.The craftsmen from Rajasthan are easily recognized because they grow the nail of their little finger or wear a small metal ring with a point to facilitate the lifting of cloth for tying. The Gujarati craftsmen, however, prefer to work without these aids to ensure no damage is done to the cloth when one works with bare hands. |

| Raw Materials The fabrics used for Bandhani are muslin, handloom, silk or voile (80/100 or 100/120 count preferably). Traditionally vegetable dyes were used but today chemical dyes are becoming very popular. Various synthetic fabrics are also highly in demand. Mostly synthetic thread is used for tying the fabric.The dominant colors in Bandhani are bright like yellow, red, green and pink. Maroon is also popular. But with changing times, as Bandhani has become a part of fashion, various pastel colors and shades are being used. The Bandhani fabric is sold with the points still tied and the size and intricacy of the design varies according to the region and demand. Bandhani forms the basic pattern on the fabric which is decorated further by various embroideries. Aari and gota work are traditional embroideries done in zari and are popular with Bandhani. These days a lot of ornamentation is done on Bandhani fabric to make it dressy and glittery for ceremonial occasions. |