JOURNAL ARCHIVE

Issue #002, Monsoon, 2019 ISSN: 2581- 9410

Kaavad is created in a small village in Rajasthan.

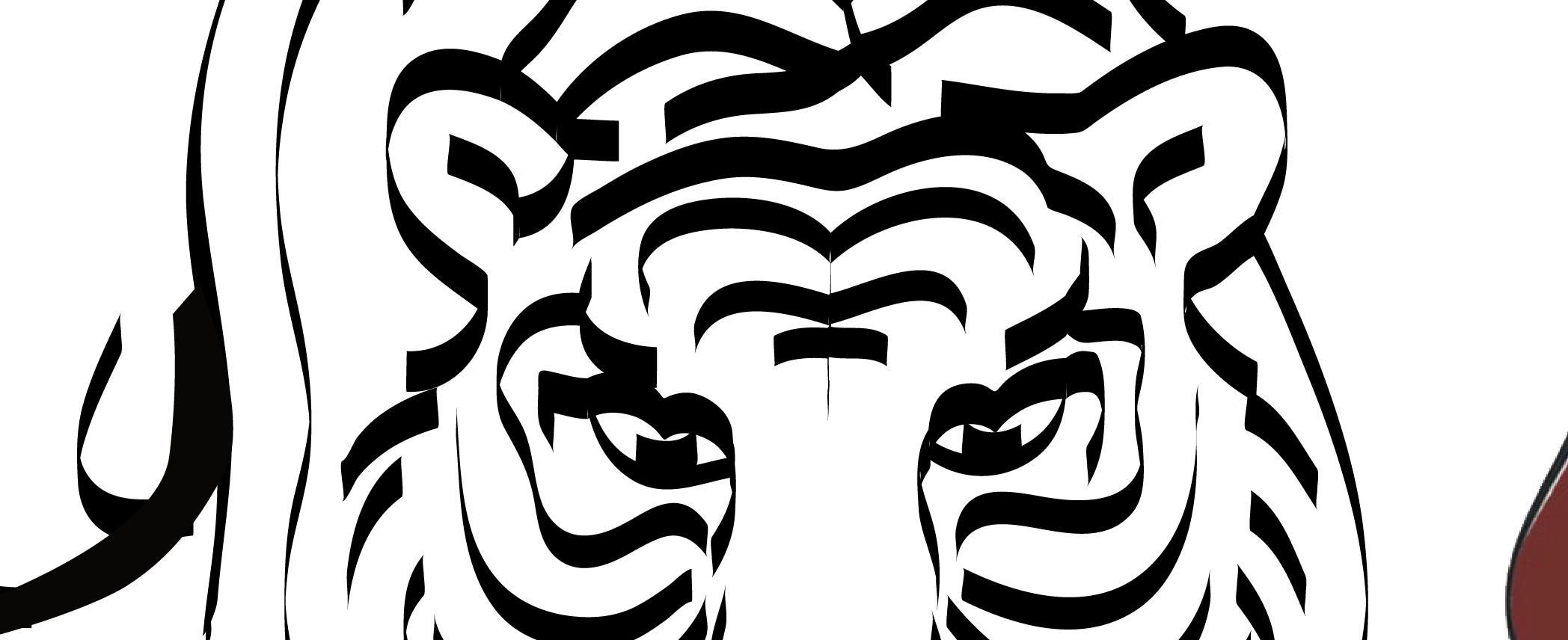

Kaavad is a wooden handcrafted and painted object. Traditionally made in mango wood this ingeniously crafted narrative device illustrates detailed figures and scenes from mythology on every panel. The rectangular shaped traditional wooden kaavad is always 12” in size for the convenience of Bhats (singers of kaavad) to travel around the villages. The kaavad is made up of wooden door that is hinged into two-three panels on each side of the door. As each panel opens the story unravels finally to the grand ending where the inner doors to the sanctum sanctorum are opened and the deity revealed for the devotees. The devotees then donate some money before the doors are shut till the next retelling. The Kaavadiya Bhat who travels from village to village with kaavad hanging from his neck recites the holy stories and maintains the family genealogies.

Kavad not just only finds association with its maker and singer but also with the patrons for whom it is sung. The last panel of kaavad is a devoted section for the patrons of Bhats. Painted in bright and vivid stones colours in red, blue, yellow, white, skin colour the shapes are usually outlined in black. The bhats instruct the Suthar to draw the figures of the patrons (called as Jajmaans) as ordered by the patrons. For example if the patron wants to see himself sitting on a camel, the image is drawn in the same way.Though the kaavad making is practised in Bassi (mewar1 region), the devotees to the kaavad reside in and around the areas of Jodhpur (marwar region).

Kavad not just only finds association with its maker and singer but also with the patrons for whom it is sung. The last panel of kaavad is a devoted section for the patrons of Bhats. Painted in bright and vivid stones colours in red, blue, yellow, white, skin colour the shapes are usually outlined in black. The bhats instruct the Suthar to draw the figures of the patrons (called as Jajmaans) as ordered by the patrons. For example if the patron wants to see himself sitting on a camel, the image is drawn in the same way.Though the kaavad making is practised in Bassi (mewar1 region), the devotees to the kaavad reside in and around the areas of Jodhpur (marwar region). Associated with legendary historical background the craft of kaavad making is more than 400 years old and has shaped into an important cultural context of Rajasthani folk art. It is said that when Shravan Kumar was taking his blind parents for a pilgrimage, Raja Dashrath accidentally killed him with an arrow mistaking him for a deer while hunting. Extremely apologetic for his deed he asked dyeing Shravan’s last wish. It is then, when Shravan asked Raja for now he would not live to take his parents for the pilgrim, he wants the holy shrine to reach his parents. As for Shravan’s parents the Kavad was symbolised as a gateway to God for the followers who are not able to take the pilgrimage. Since the by gone era it was embedded in the tradition of Rajasthan.

Associated with legendary historical background the craft of kaavad making is more than 400 years old and has shaped into an important cultural context of Rajasthani folk art. It is said that when Shravan Kumar was taking his blind parents for a pilgrimage, Raja Dashrath accidentally killed him with an arrow mistaking him for a deer while hunting. Extremely apologetic for his deed he asked dyeing Shravan’s last wish. It is then, when Shravan asked Raja for now he would not live to take his parents for the pilgrim, he wants the holy shrine to reach his parents. As for Shravan’s parents the Kavad was symbolised as a gateway to God for the followers who are not able to take the pilgrimage. Since the by gone era it was embedded in the tradition of Rajasthan. Traditionally, the Mango tree wood was used, but now Aadu timber is used. The wood is available in abundance in the forests around the village. The woods are mostly cut by Muslim community of the village as wood cutting is not considered righteous in Hindu community. The raw material is in abundance and easily available as the village is located in the Arravali hills. The hills are a rich source of timber. The timber is first procured in the log form which is cut into smaller blocks of wood and flat pieces to be used for kaavad making.

Traditionally, the Mango tree wood was used, but now Aadu timber is used. The wood is available in abundance in the forests around the village. The woods are mostly cut by Muslim community of the village as wood cutting is not considered righteous in Hindu community. The raw material is in abundance and easily available as the village is located in the Arravali hills. The hills are a rich source of timber. The timber is first procured in the log form which is cut into smaller blocks of wood and flat pieces to be used for kaavad making. Gum is used to make colour paste viscous enough to stick to the wood. The gum along with appropriate amount of water is mixed with powdered colour. The gum was earlier brought by the Bhils who bartered gum for food or money. Now the gum/Gond is easily available in shops. The craftsperson buys gum available with the tribals. Non availability of gum sometimes causes them to buy from shops.

Tools

The tools are basic tools used in carpentry. The vernacular names of the tools are as follows:

Gum is used to make colour paste viscous enough to stick to the wood. The gum along with appropriate amount of water is mixed with powdered colour. The gum was earlier brought by the Bhils who bartered gum for food or money. Now the gum/Gond is easily available in shops. The craftsperson buys gum available with the tribals. Non availability of gum sometimes causes them to buy from shops.

Tools

The tools are basic tools used in carpentry. The vernacular names of the tools are as follows:

- Basola

- Reti

- Tankla

- Badi Reti

- Guniya

- Kasariya

- Prakaar

- Jammur

- Radda

- Hathodi

- Fine Reti

- Karot

Conclusion

Folk art lives the culture of a region. Rajasthan offers myriad instances of the living heritage. The tradition of kaavad making and singing also takes us to an exhilarating path of spirituality and wisdom where the simplest of hand tools can craft an ingenious art of cultural importance. Stories of Kaavad mirrors the illustrated past of Indian tradition and heritage that essentially forms the root to a growing tree of knowledge and wisdom.

Unfortunately the recent trends have undermined the potentially strong source of educational tool that a Kaavad is. Story telling has been and will remain the most engaging and amazing way to shape not only young minds but to direct the adults at the time of confusion. The idea of using a kaavad as an asset for educating the young minds is a sustainable goal yet to be achieved.

References

Erstwhile pre-British era the region of Rajasthan was divided into eastern and western cultural zones divided Aravalli hills. The eastern zone comprises of 4 main cultural zones Dhunhar, Mewat, Harauti and the Mewar while the western side is the Marwar cultural zone. As given in U. B. Mathurs Folkways of Rajasthan.

Conclusion

Folk art lives the culture of a region. Rajasthan offers myriad instances of the living heritage. The tradition of kaavad making and singing also takes us to an exhilarating path of spirituality and wisdom where the simplest of hand tools can craft an ingenious art of cultural importance. Stories of Kaavad mirrors the illustrated past of Indian tradition and heritage that essentially forms the root to a growing tree of knowledge and wisdom.

Unfortunately the recent trends have undermined the potentially strong source of educational tool that a Kaavad is. Story telling has been and will remain the most engaging and amazing way to shape not only young minds but to direct the adults at the time of confusion. The idea of using a kaavad as an asset for educating the young minds is a sustainable goal yet to be achieved.

References

Erstwhile pre-British era the region of Rajasthan was divided into eastern and western cultural zones divided Aravalli hills. The eastern zone comprises of 4 main cultural zones Dhunhar, Mewat, Harauti and the Mewar while the western side is the Marwar cultural zone. As given in U. B. Mathurs Folkways of Rajasthan.

The search of Adivasi textile craft turned into a reality yatra to Bastar and Kotpad. As usual the start of every journey begins with train yatra connecting cities to towns and towns to rural villages. It was peak of summer 2000; I was still studying at NIFT. Along with other classmates, Ireached Raipur station from Delhi and then to Bastar in a state transport bus cutting around the steep edges of the hills. I remember, the initial two daysof experience at a dingy local lodge turned into excitement when we found an accommodation in a forest guest house and a jeep with the help of local IAS officers. Little did we know that our excitement and fantasy of Adivasi land will turn into nightmare,until we faced the first encounter at the guest house? As we peeked inside the guest house we saw the care takers sleeping upside down on the couch in the lounge area, eyes half closed and the stench of local liquor all over the room. Everything appeared very absurd and not so good feeling about the space and place. But we had no choice. So, this was the opening of our journey and start of more such excitement to come. There was a small ground for haat in front of the guest house which was often crowded early in the morning. Sometimes, I used to go with my sketch book and draw women selling vegetables. Some of them would pose for me and rest of them would pierce their eyes inside my sketchbook. I loved it and admired different expression of different people. Sketching was fun. It was one of the ways I captured people in my memories, my thoughts and imaginations. I sketched people sitting, chatting and doing other job work. Morning routine started with visit to villages Tokapal, Nagarnar and Kondagoan to study textiles, dhokra casting, and terracotta and wrought iron though textiles remained our focus area. Tokapal and Nagarnar villages were our main centres to learn about traditional Bastar textiles.My Bastar Yatra was my first field trip when the agitation for Chattisgarh state was going on. Whist travelling inside the remote villages I admired the space of weaver’s abode and small mud house of Adivasi people with thatched roof and the local objects.Looking at Adivasi womenengaged in different activities and the innumerable stories I heard, it was inspiring, to learn, unlearn and capture memories inside the camera, diary and my sketch book.While doing research work for one month in the Adivasi land, travelling five to eight villages was like an experience in itself. The sight of flowering mahua trees, women collecting mahua, gourd hanging around the shoulder and people fishing using local fish traps was enchanting but at the same time hard realities of life also struck my mind when we saw middle men cheating artisans, master crafts person exploiting small artisans, people starving for basic amenities and I cannot forget the obnoxious trader selling dyed colourful chicksin the Jagdalpur market to attract customers. Research work started with textiles as the prime area of research documentation. Weaver’s of Bastar had an interesting story to share. Weavers claim themselves to be Panika-the followers of Santkabir. Kabir was a weaver and a poet from Banaras, preaching the union of Ram and Rahim –the beliefs of Hinduism and Islam. Panika’s ancestors migrated to this region several hundred years ago and adapted the local Adivasi traditions of region. Panika people belief in Kabir and weave the cloth for Adivasi communities. Kabir is the dharm of Panika people.The cloth of Kabir shares syncretised relation between two different communities.The cloth or pata of Kabir is adored by Adivasi people. Once upon a time, it was worn by the entire Adivasi community. Sharing local traditions together, Panika and Adivasi communities were interdependent on each other. Panika sing the folk songs of Kabir and believe in nature god like Adivasi. Their belief reflects in the textiles.The material culture narrates how local stories travel, beliefs and patterns of nature are incorporated into textiles. With time, culture and practices change. The weaving tradition of Adivasi pata reduced with the advent of mechanised factory produced material available in the local market. The story of Adivasi cloth still breathes with handful of Kabir weavers. The two weavers Sindu Das andVijay Kumar Das from Bastar narrated innumerable stories and superstitious beliefs related to Adivasi cloth. Sindhu Das commitment to create exclusive textiles and Vijay Kumar’s dedication to Kabir dharma opened up several nuances of Adivasipata. In the year 2009-10 Small Study grant (India) from Nehru Trust for the Indian Collections at Victoria and Albert Museum supported me to pursue my research on Adivasi textiles and the methods of natural dyeing from the border area of Odisha and Bastar. I was visiting almost after almost a decade. There was shift in the lifestyle of people which I guess is inevitable. Culture keeps shifting and altering, so is the social and cultural context of region and the people in relation to material culture. Panika weavers who have retained the age old tradition of weaving and natural dyeing are still struggling for sustenance. The following research abstract is gist of NTICVA work which was later published in Imagining Odisha book, Praffula publication in 2013.

Indian art is dominated by two major elements nature and religion. Man has been fascinated by the nature form the very beginning and tried to understand the power and wealth of it. Time to time, he also got frightened with nature and started worshiping it, as one finds the concept of nature inspired god-goddess in the beginning. Later on, during the royalty/federal setting, one come across the artistic activities influenced by religion and temple gave the momentum to spread then prevailing religions, Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. Soon these places became the cultural activities center throughout the country and nature got prominent place in the artistic expression of the artists of India. While representing the early art, artists had often picked up nature based motifs to express different aspects and mood of human being. This trend can be witnessed throughout theIndian art history and gives the unique distinctiveness to the Indian art, which has been admired globally. The imaginative and sensitive artist had often illustrated full blossom flower to show the joy of human being. Similarly depiction of fruits in art was to symbolize the fertility, sun to represent day, moon and starts to portray night and so on. In fact nature had played a vital role to understand the art in a more meaningful manner. Almost all the elements of nature, except fruit have been extensively portrayed from sculpture to painting and religious art to utility art. Banana, grapes, jackfruit, pomegranate and mango are the few fruits which were often depicted in Indian art. Among all these fruits, mango is one such fruit, which has got maximum importance from all corners, whether it is literary acknowledgement, religious, sensitive and artistic expression. Here is an attempt to look at the journey of mango motif from fruit depiction to ornaments motif used for architectural decoration to jewellery motif to objects of day to day life and the final culmination of mango motif is as floral buti known as kalka, kalgha, kairi developed by textile designers. Mango in Indian Literature Indian literature gives numerous references of fruits, its importance in daily life as well as ritualistic life, which indirectly informs many aspect of environment and flora-fauna of that period. It is believed that before starting agriculture man was initially depended on fruits. There is little reference of fruit trees in Rigveda, but increased in Brahmanical literature. Epics, purana's, kavya and other Hindu, Jain and Buddhist literature provide various references of mango. The first reference of mango tree as 'amra' is mentioned in Satapatha Brahmana. Lots of references of amra occurred in both the epics. The Aranyakakancja in Ramayana and Vanaparva of Mahabharata mentions the frequent use of mango beside other fruits, which were offered to the guests, sages and visitors who use to visit Ayodhya princes and Pandvas at the time of their exile in forests. The most vivid description comes from different puranas about the mango fruit, leaves of mango tree, its wood and tree etc. Brahmavaivarta Purana has listed number of fruits and amra is also metioned, Vamana Purana informs the name cuta besides amra for mango, Varaha Purana also refers both the names for mango. Vayu Purana mentions the word amra for mango. Bhagavata Purana also mentions that mango tree is present on mountain Mandar Puranas give the importance and benefits of planting tree for common man and it further records that, who plant five mango trees during his life, will never go to hell. The most interesting reference of amra comes from Matsya Purana, which records the tradition of donation of fruits to sages by devotee. It further says that in absence of fruit (possibly during the off season) donating metal fruit was suggested and prescribes sixteen type of fruits can be made of gold, silver or copper that according to their own status a devotee should procure and donate to sages. Here the mango fruit is in the list of fruits recommended to be made of copper. Literature of Kalidasa, Amarkosa and Navasahasrankacarita" and Divyasrayamahakavya" text of historical mahakavya of mediaeval period also gives references of mango fruit. The Purarnic and Kavya literatures refer the mango fruit, its different names and its use. Importance of mango in daily and ritualistic life also been mentioned in different literary texts. Tradition and Importance of Mango Tree Hindus consider the mango tree as symbol of Prajapati, Lord of all creation. Among all the fruits, mango is considered sacred and important, as all its parts are very useful in human's life. Mango leaves and wood were considered to be very auspicious for ceremonial use and ritualistic customs in the past and tradition still exists. Such as, tying the mango leaves at entrance doorframe of Hindu's house on every auspicious occasion is still being practiced. Mango wood remains the best for hawan (auspicious fire worships) in every Hindu's household and similarly mango fruit, considering the symbol of fertility, is often given to house lady at the time of ritual ceremony. Mango tree is also associated with marriage of Siva-Pdrvati. As per temple belief Siva-Piirvati reunited under a single mango tree with the help of her brother Visnu." Therefore the name Ekambaranatha (Eka-one; amra-mango and natha-Lord) was given to lord Siva which is being called today as Ekmbareswara. It is believed that 2500 year old mango tree is inside the Sri Ekambaregwar temple compound, which is in Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu, which is the famous seat of Hinduism. This temple was made during the Pallava period (8th-9th century). Beside tree, as per popular belief this temple also has 3500 year old trunk of mango tree, which is being worshiped by all devotees who visit the temple even today." (Author witnessed during personal visit to the temple in September 2010) One of the pillars in the main mandapam of his temple depicts the Tapasvani Parvati doing penance under mango tree as mentioned in literary texts that Tapasvani Parvati did her tapasya (penance) under the mango tree. Buddist consider the mango tree holy ever since Lord Buddha was presented with a groove of mango tree He performed an important miracle of Srawasti under a mango tree. A pillar from Bharhut, dated 2nd century B.C., illustrates the mango tree. An architectural panel form Bharhut stupa of Suriga period beautifully illustrates the bunch of mango fruits in between the story of Dabbhapuppha Jataka. The famous jain goddess Ambika, who is also known as Amba, Arnbalika, Ambali and Ambi is an important Yaksi goddess of Jain iconography. Concept of mother goddess always portrays her as she holds baby on her lap. Iconographic texts referes that four armed goddess always sits under mango groove and holds amra-lumbi, bunch of mango, in her one of hand. The earliest known example of Ambika is from Aihole, Bijapur, Karnataka, which is dated to mid 7th century A.D. As per literary sources of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, mango tree gets due importance and also well documented and beautifully illustrated in early Indian art The foremost example is concept of salbhanjika always illustrated by yaksi holding branch of tree, which is full of fruit, leaves and flowers. Quite often mango tree is being represented in early examples of yaksi. Indian art has several such examples; one such example is from the northern gateway of great Sanchi stupa dated 1st century B.C. where yaksi is holding branch of mango tree, which is full of mango fruits. Mango tree is also illustrated in sandstone pillar of Suriga period (2nd century) where Suvarna Kakkata Jataka has been depicted. Similar composition is evident in Gupta period sculpture from Deogarh, Madhya Pradesh, dated to 4th-5th century A.D. It depicts Rama, Laksamana sitting with guru Vasistha under mango groove." Divine lovers, sitting under a mango tree, is a beautifully representation of sandstone sculpture from Nachna Kuthara, Madhya Pradesh. Similar mango grooves are evident with Jain goddess Ambika’s and so with Buddhist images too. Early depiction of salbhanjika holding branch of tree, which remain full of fruits, flowers and leaves, Hindu, Jain and Buddhist god and goddess were also shown sitting under mango groove which clearly shows the importance of mango tree throughout its history. Mango Shape Adopted as Decorative Motifs The mango remain associated with human's day-to-day life, its importance has being described in literature also and probably its roundish curved shade, which has many element from design point of view might have inspired the artist to work on it. Therefore some of the early Indian art sculptures illustrates that mango shape adopted as a decorative motif. The earliest example of mango shaped motif used in architectural decoration is available from Suriga period, which is dated to 2nd century B.C. Tow red sand stone pillars from Amin, Haryana (displayed in the gallery of National Museum, New Dehli) illustrates yaksa image and amorous couple on the front side, while back of both these pillars depicts floral pattern having border of mango or kalka pattern all around. A pillar from Bharhut, 2nd century B.C., depict dream scene of queen Maya Devi in the centre medallion and interstingly its side border on lower portion depicts branch of mango tree with mango fruits. As mango fruit is considered a symbol of fertility so depiction of mango branch here is quite appropriate. Mango shape adopted in Jewellery and Decorative Arts Objects Mango shaped motif was also used for ornamenting jewellery items like head ornament, bajubanda (armlet) and necklace from 1st century A.D. onwards. The Kusana period Naga and male head depicts mango shaped (upside down) jewel inside turban. This style of head ornament reminds the later period sarpech, which is feather like turban ornament. Sarpech, known as jigha/kalghi also, is fixed on turban in the cener and it became very poplar during Mughal and provincial courts. Slowly and gradually wearing sarpech became so fashionable that in Punjab region, at the time of wedding, it has became compulsory to wear kalghi in turban by the grooms. Beside head ornament, kalghi shaped ornament was also noticed in the example of bajubanda in Gandhara style of stone sculptures of Kusana peiod. A schist stone Gandhara sculpture illustrates images of jewelled Avalokitesvara. He wears bajubanda, which illustrates many mango motifs arranged in ornamental design. such depiction can also be seen in image of Visnu and various god-goddess of Pala period. One such image of Lord Visnu depicts the stylized form of kaighi or mango pattern beads used in necklace and bajubarida also, as depicted in Taxila gold jewellery and in some stone sculptures too of later period Several example of mango shaped sindurdani (collyrium container), perfume bottle, huqqa base, flower vase and lime boxes from 17th century A.D. These artifacts were made of different material like silver, brass, bidri ware, ivory and semi precious stones with various techniques. Artistically created these objects at Rajasthan, Delhi, Bidar (Deccan) and many other centres clearly reflect that mango shape was very popular. Such simple and elegant shape was extensively used by artists for creating artistic things of daily utility as well as luxury things. Mango or Kalka motif on textiles The final culmination of mango motif was its introduction in Indian traditional textiles, which is known as kalka, kalgha, cari, keri, kairi, kuniabuta etc. Cotton. silk, wool all three fibers were used by the weaver, printer and embroidered to create artistic textiles and costumes. Popularity of kalka motif on Indian textiles was so much that besides domestic market such textiles were extensively produced for export market also in England, Eurpoe, South East Asia, Africa and many other parts of the world. This also inspired the French and British designers to initiate its production in their countries, which is popularly known as Paisley in the international textile market. 'Paisely', 'palm', 'tear drop pattern', boteh/buta/cone', 'pine', 'keri' and 'kalgha are the terms used by textile experts for this mango shaped kalka motif so far Frank Ames has suggested that this motif was developed in Persia and in 16th century when Kashmir and Persia enjoyed the close association it was adopted in Kashmir shawls. Monnique Strauss is off the opinion that either it has first appeared in Persia or India. She suggests the word 'pine' is most widely used in the English speaking world, Sherry Rehman and N. Jafri prefers the term 'keri', which has come from mango." 'Kalgha' word has been referred by Goswamy while describing the pattern of Kashmir shawls." Usually the row of kalka motifs found on the pallu (end panel) of Kashmir's shawls, path-a, dosalla etc. in 18th century. It is a fact that early Indian textiles in lesser number have been reported so far, but continuity of Indian art provides some very interesting references that this kalka motif has been carved on the costumes of images carved in stone and ivory besides other art forms prior to 18th century. More importantly some of the printed and cotton textiles specimens provide important links, which are dated to 15th century and found at Fustat, and South East Asian countries. Indian textiles and costumes from the very beginning are known for floral decoration and more importantly quite often similar illustration is available on plastic art too. Terracotta, stone and bronze sculptures of different period beautifully illustrate the floral pattern, geometric designs and stylized ornamental motifs on attire of divinities and other carved figures. Wall paintings at Ajanta, Aurangabad, Maharastra, and paintings on Bagh cave at Madhya Pradesh, which are dated to 2nd to 5th century A.D. illustrates the numerous textile and costume design. These paintings provide good overview of floral pattern decorated costumes used by royal, dancer, courtier, soldiers and common man also. Jain pata paintings and miniature paintings of 5th-6th century also gives the continuity of same tradition. Birds, flowers, fruits and geometric patterns have been extensively found on attires, bed spreads and furnishings in number of early Indian art work. Besides paintings, sometimes the stone and bronze sculptures also provide important references in this regard. Some of the images portray their outfit beautifully decorated with ornamental pattern. One such stone sculpture of Mohini (lady with mirror) is evident from Gadag, Dharwad district of Karnataka, Southern India from 12th century A.D. Bejewelled and well dressed Mohini stands under mango grove in tribhanga posture, like salabhanjika of early period. The dhoti or sari of Mohini is beautifully decorated with stylized kalka buta with two leaves. This is a first clear example of use of kalka motif for decorating the textile known so far. Under the Bhillama rulers in the western Chalukayas of Kalyana this region flourished in art, culture and also important trade center, which were connected with other parts of the country. Number of stone sculptures of this period gives evidence of artistic execution of mango tree, mango fruit and its leaves in stylized forms. These example show that kalka motif was adopted on textiles somewhere in 12th century probably in Karnataka region. Similar style of motif is also found on textile fragment found at Fustat, Egypt and Heirloom from Sulaveshi, Indonesia, which is dated to 14th-15th centuries A.D. Fustat piece, depicts the mango with leaves design, which resembles Mohini's attire pattern." Long piece form Sulawesi depicts stylized trees, single leaves and one of the trees bears fruits, which resembles the mango fruit. Both these cotton specimens are painted and printed in blue and red colour with mordant dye and paint. It appears that this kalka motif was first used in Southern or western part of the country. As textiles extensively travelled from one part to another, therefore probably this motif was also adopted by many textile artisans from west to east and from east to north for decorating textiles and Kashmir took lead in popularizing the motif through shawls. For making this pattern known around the World in 18th century French and English shawl designer contributed a lot. At first, French agents reached Kashmir so that they can improve the traditional designs. The British shawls were made in 1784 by Edward Barrow of Norwich, which developed the pioneer center of imitation shawl industry in Europe. Edinburg weavers were probably the first to imitate the Kashmir motifs and texture as well. By 2nd half of 18th century Paisley, which was few miles to the south west of Glasgow, took lead for producing shawls. Paisley centre started as offshoot from Edinburg, but soon became more popular internationally. Conclusion Some scholars suggest that kalka motif has Persian origin; however the importance of mango tree, fruit and leave is very strong in Indian ethos right from the beginning. Literary evidences inform about the daily utility of mango tree, leaves and fruit besides its ceremonial and religious customs. The use of the shape of depiction of mango tree and fruit in Indian art is also well reflected. Indian artisans had used the shape of mango in many ways and kalka motif is one of them. Therefore, it is possible that creative and imaginative Indian artists had taken liberty of using the mango motif or kalka in textiles from 12th century onwards may be from southern or western India. Kalka or kairi buti have been extensively used for decorating the Indian textiles from the length and width of the country, especially from 18th century onwards. Examples of the three material worked in almost all the prominent techniques. Numerous textile examples are available illustrating the haw motif such as woollen shawls from Kashmir and silk and zari brocaded Banarsi sari (north), cotton printed table covers from Masulipatinam (south), printed yardage from Gujarat and Rajasthan (west), silk Baluchari sari of Murshidabad (east), embroidered chikankari coverlet of Lucknow (north) or kantha coverlet (east) and many more. The design of kalka also spread all over the world like its sweet smell and taste, which remain the most favourite fruit among Indians of all ages and period. Further Reading

- Satapatha Brahmana, XIV.7.41.

- Brahmavaivarta Purana, 13.28.30.

- Vamana Purana, 6, 105; 12.51, 17.52; 58.8.

- Varaha Purana, 55.42; 146.64; 168.24; 39.44.

- Vayu Purana, 69.307; 69.308.

- B.L. Mall, Trees in Indian Art, Mythology and Folk Lore, New Delhi, 2000, p.36.

- Matsya Purana, 96.9.11.

- Kumarsambhava, 3.32.

- Amarkosa, 88.33

- Navasahasrarikacarita, 1.33; vi.779.

- Divyasrayamahakavya, xvi.73.

- B.L. Mall, op.cit., p.40.

- D.D. Shulman, Tamil Temple Myths, USA, 1980, pp.171-172.

- S.P. Gupta (ed.), Masterpieces from the National Museum Collection, New Delhi, 1985, p.97.

- S.P. Gupta (ed.), op.cit., p.101; M.S. Randhawa, Cult of Tree Worship in Buddhist-Hindu Sculptures, New Delhi, 1964.

- P. Pal, The Sensuous Immortals, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1977, p.48.

- S.P. Gupta (ed.), op.cit., p.132.

- M.N.P. Tiwari, Ambika in Jain Art and Literature, Delhi, 1989, p.16.

- Ibid., p.17.

- Ibid., p.21.

- S.P. Gupta, op.cit., pp.93-104.

- C. Sivaramamurti, The Art of India, Japan, 1966, p.300.

- V. Dehejia, Discourse in Early Buddhist Art, New Delhi, 1997, p.91, fig. 63.

- C. Sivaramamurti, The Art of India, New York, 1977, p.446.

- B.N. Goswamy, Essence of Indian Art, San Fancisco, 1985, p.33, pl. I.

- S.P. Gupta, op.cit., pp.114-132.

- C. Sivaramamurti, op.cit., p.280.

- Buddha in Indian Sculptures, Austria Exhibition Catalogue, April-July, 1995, pl. 80, p.131 and pl. 55, p.98.

- F. Ames, Woven Masterpieces of Sikh Heritage, U.K. 2010, pl. 1.

- S.P. Asthana, Taxila Jewellery, (ed) S.P. Gupta, Masterpieces from the National Museum Collection, Delhi, 1985, p.225.

- Alamkara, Singapore Exhibition Catalogue, Ahamdabad, 1994, pp. 110 and 112.

- F. Ames, Woven Masterpieces of Sikh Heritage, U.K. 2010, p.

- 33. M.L. Strauses, Romance of the Kasmere Shawl, Ahmedabad, 1986, p.11.

- S. Rehman and N. Jafri, The Kashmir Shawl, Ahmedabad, 2006, pp.300-302.

- B.N. Goswamy, Piety and Splendour, Delhi, 2000, p.190.

- K. Desai, Jewels on the Crescent, Ahmedabad, 2002, pp. 4, 41 and 73.

- Ibid., p.78.

- D.C. Ganguly, The Struggle for Empire, (ed) R.C. Majumdur, vol-v, Bombay, 1957, pp.185-186.

- K. Desai, op.cit., pl. 41; P. Pal, op.cit., pl. 84; C. Sivaramamurti, op.cit., 1977, pl. 446-293

- M. Gittinger, Master Dyers to the World, Washington D.C., 1982, p1.42, p.54.

- R. Crill. Trade, Temple and Court, Mumbai, 2002, pt. 3, p. 20.

- John Irwin, Shawls, London, 1955, p.15.

- Ibid., p.19.

- Ibid., p.20.

- Ibid., p.23.

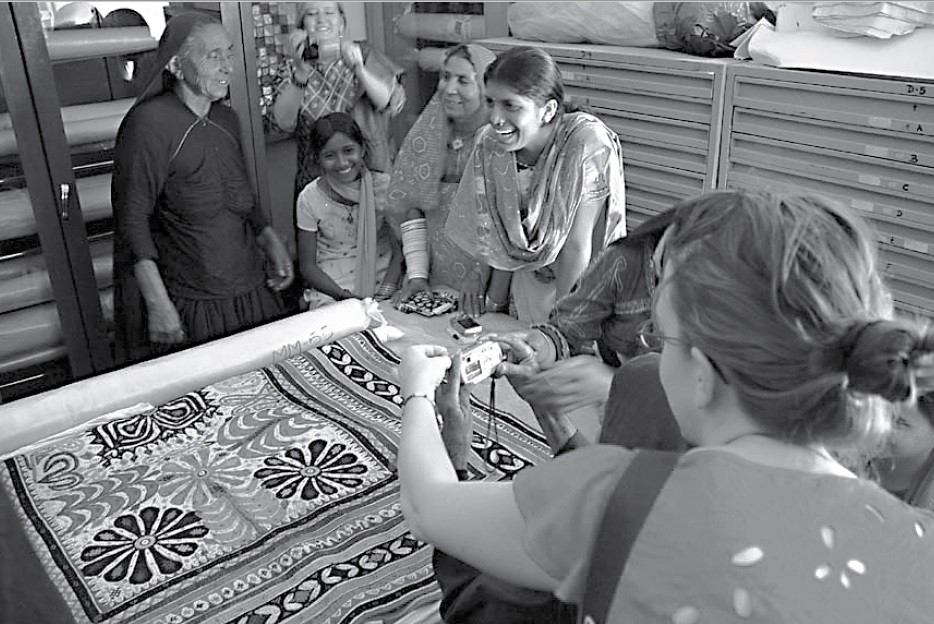

| Kala Raksha has emerged as an important force and influence in the effort to preserve and sustain India’s craft heritage, as well as for understanding its contemporary relevance. Mahatma Gandhi and those who struggled with him for independence recognized the central role of handcraft to India’s civilization, values and aspirations. In the complex transition from a colonial economy to industrialization and development that followed freedom in 1947, India became the first country to integrate craft into national planning. Although much has been achieved since then, the craft sector is in crisis. Globalization, the pressures of consumerism, changing lifestyles and conflicting notions of modernity have all combined to make this a critical moment for the sector. The need is to demonstrate the relevance of craft to sustainable livelihoods for millions of Indians, and as a means for empowering those who remain at the margins of society and of what many consider ‘progress’. Kala Raksha has demonstrated the relevance of craft as an important opportunity for sustainable rural livelihoods in one of India’s harshest environments, as well as the relevance of crafts to wider issues of empowering women and the marginalized. Kala Raksha and the Kala Raksha Vidyalaya have together helped to bridge the gap between the traditional knowledge held by rural communities and the demands and opportunities of new and changing markets, demonstrating that these links are possible without damage to the integrity of cherished values. In addition, and perhaps most significantly, Kala Raksha has worked to remind us all that crafts have an importance beyond incomes as a force for identity and self-worth in an era of such rapid change. The Kala Raksha Vidyalaya is perhaps the first effort of its kind, bringing contemporary design education to those for whom access is most often denied because of poverty, illiteracy and gender. This in itself is a huge, revolutionary achievement which can have a ripple effect of enormous significance to India and the world.

|

| At a Symposium on Indian Textile Traditions at the Artisan students, staff and jury members began the first annual Convocation Mela of Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya with great anticipation. From 21-26 November 2006, the graduating class of 2005-06 proudly presented their collections for spring-summer 2007 on the beautiful rural Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya campus in Tunda Vandh, Mundra Ta, Kutch. The first ever professional collections completely designed, produced and presented by traditional artisans of Kutch included home furnishings, accessories and garments in themes of nature and culture. The students also included documentation of their courses on colour, concept, market trends, finishing and presentation. |  |

|

From 21-23 November, the collections were juried by eminent experts in art and craft, including Ashoke Chatterjee, Gulshan Nanda, Jaya Jaitly, Laila Tyabji, Subrata Bhowmick, Darshan Shah, Debbie Thiagarajan, and Sheela Lunkad who gave valuable, lively and professional feedback to the graduating students. |

|

On the 23rd evening, the four day public mela was inaugurated by the Convocation ceremony, presided by Maharao Shree Pragalmalji and Maharaniji Priti Devi of Kutch and coordinated by Compere Chandrapal Bhanani. Honoured guests were greeted by members of the Kala Raksha family. Director Judy Frater, Advisor Dr. Ismail Khatri, and Jury Members Subrata Bhowmick, Laila Tyabji, and Ashoke Chatterjee spoke about the confluence of craft, design, market and education that is needed for artisans to succeed today. The Maharani and jury members presented graduation certificates and colour wheels donated by The Color Wheel Company to each of the twenty-five students. Prizes were awarded for Best Collection, Best Presentation, Most Marketable and Most Improved. Maharao Shri Pragmalji gave the keynote address in Kutchi language, much to the artisans' delight. The evening concluded with dinner, followed by the premier of "The Kala Raksha Story: Nurturing the Art of Craft", a short documentary by Parthiv Shah, and a concert of traditional Kutchi music. |

|

|

On the 24th evening, the students' final collections were showcased in an elegant and glamorous fashion show choreographed by Utsav Dholakia. Triumphant artisans walked the ramp alongside lovely models. The local people were thrilled with the events, never before seen in this region. The 25th evening local groups presented their music and dance. From the veiled welcome song to the ebullient "sanedo" of students and friends, this was a richly varied cultural program, and a fitting grand finale. |

|

All evenings were attended to standing room only. In the three days of celebration, over 6,000 people visited the campus. Days saw visitors trying their hands at block printing, pottery and embroidery, with guidance from artisans in the KRV studios. They enjoyed spontaneous concerts of folk songs, and Kutchi food, and took trips in camel and decorated bullock carts to the neighbouring Rabari village, Vandh. But most of all they appreciated the exciting new craft designs. The students earned over Rs. 1,00,000 in direct sales - unprecedented in a rural Kutch event. Orders were placed for about the same amount, giving encouragement to the new designers. |

|

|

Sadly, the celebration was marred by the fact that the lush campus, its dormitories, studios and exhibition hall all painstakingly constructed in traditional building techniques - as well at the world famous Rabari village, Tunda Vandh, are slated to be the site of two large power plants. |

Executive Summary Background

- Income Generation

- Deeper Issues

- Concept of the Design School for Artisans

- Rationale and Structure

- Building Market Knowledge and Market Linkages

- Funding

- Design Instruction and Institutional Links

- Construction of Facilities

- CAD Center

- Equipment and Tools

- Kala Raksha Museum

- Conservation of Objects

- Mobilization

- Objectives

- Expected Results

- Project Management and Expertise

- Marketing Experts

- Faculty Trainees

- Mentors

- Business Plan and Marketing Strategy

- Establishing Data Bases

- Developing Market Orientation and Teacher Training

- Instruction

- Participants

- Expected Outcomes

- Course Content

- Convocation/ Jury/ Exhibition

- Future Plans

Introduction Traditional crafts are endangered. The attention focused on craft today attests that we recognize this fact. Artisans struggle to earn wages that may not even equal those of manual labour. The social status of the artisan is still sadly low. Moreover, the social mobility of artisans is limited by chronically low levels of education; and the perceived irrelevance of the education available perpetuates the status quo. A spectrum of Government offices, programmes and schemes, as well as non-government organizations are trying many ways to save traditional crafts. There are various forms of subsidy, bazaars and melas organized for marketing, Master Craftsman and Shilp Guru awards, and seminars to raise awareness and respect. But the fact is the Shilp Gurus, those craftspersons most highly honored, are still asking for the most shockingly basic facilities- a place to work, a railway pass, free admission into museums- to see their own heritage! And they protest that in the committee to select Master Crafts persons, there is not a single artisan. Something is not working. To foster genuine sustainability, to restore the vitality of traditional craft, these issues must be addressed by artisans themselves. To enable this, we must address the most pressing need in India today: relevant education for rural people. TRADITIONAL CRAFT Traditional crafts existed integrated into local social systems. Some crafts, typically those done by men, such as block printing, hand weaving and pottery, were professional. Others, typically those done by women, such as folk embroidery, were personal and never thought of in commercial terms. Regardless of commercial orientation, the user of the craft was intimately known. Design was an integral part of craft. The artisan was designer, producer and marketer simultaneously. S/he knew which design would be used by which person, because there was a direct connection between aesthetic style and culture. Designs evolved; innovation is critical to living art. But the changes were slow, subtle innovations within a tradition... a pattern within a pati, a new fiber or colour for the border of the traditional dhablo (blanket). If interaction was required, the user interacted directly with the artisan. CHANGING TIMES, CHANGING MARKETS In the last few decades, these traditional crafts have undergone tremendous change. As local villagers seek cheaper mass produced functional wares, artisans are compelled to find new markets. Fortunately, at the same time sophisticated urban markets have welcomed the concept of traditional crafts. However, traditional work is often not saleable because the object itself, its colour, style or price are not appropriate to the current market. These crafts must adapt to their new clientele. Since the new market is no longer local, nor are crafts necessarily produced for utilitarian purpose, the functional basis that drove innovation is altered. In addition, since the market has expanded, innovations must now be faster and less subtle. Instead of varying the pattern within a pati, the pati itself must be changed. A different consciousness is essential for craft to succeed in this market. THE DIVISION OF ART AND LABOR With these major changes in the market for handmade products, it has been recognized that new design is needed to make craft sustainable. Conventionally, this has been perceived as a need for design intervention. It is assumed that intervention takes place in the form of trained designers giving new designs to artisans, the implication being that designers have knowledge that enables them to conceive of aesthetically appropriate products, while artisans have the skills to produce such designs. Artisans are asked to make what someone else tells them to make, rather than work from their own sense of aesthetics. This can result in dis-empowering artisans if it is done without explanation or means of access. I recall vividly an incident in which patchwork cushion covers were being sorted by staff and designer into good and bad piles. One senior artisan, observing, became increasingly agitated. When her own piece went into the reject pile, she visibly resigned, exclaiming, "Then just tell me what to do; I don't know what you want." In another instance, a group of Jat women who do cross stitch embroidery and had been working commercially on block printed patterns for some time refused to take on new work without a pattern printed on the cloth. They had given up their confidence in their traditional art, which of course is worked out by counting. A third, telling incident comes from Rabari embroiderers. When presented with a set of four alien coloured threads, Rabari women balked. "If we use these, it won't be Rabari," they said. In traditional work, there is no distinct separation of colour, stitch, pattern and motif; these work together in units. Design intervention separates these elements and juxtaposes them in new and, for the artisan, cryptic ways. Simultaneously with design intervention, design, or art, is separated from craft, or labour. When design is reserved for a professional designer and craft is relegated to the artisan, the artisan is essentially reduced to a labourer. The separation of designer and artisan thus elevates the status of the former and lowers that of the latter, reinforcing the low social status of craft. One further concern about the separation of design and execution of craft is that it supports the factory model. This seems to emanate from an assumption of an industrialized society. If craft tries to compete with industry, it will surely fall short, in terms of manufacture and in terms of price. The personal character, the intimacy, the hand made quality itself is what will enable craft to survive in an industrial world. The strength of hand craft is that it expresses a whole world. This concern invokes the long-standing discussion on the distinctions between craft, art, and design. Craft implies skill, doing, a hobby or practical profession. Art implies creativity, imagination, expression. Design implies mediation. Craft has always been design based because it relies on a consumer. Craft, like design is fundamentally based on satisfying the user's aesthetic needs, rather than purely expressing feelings. But in a sense, traditional craft was really traditional art, in that the maker managed concept as well as execution. Depending on the level of professionalization, laborers would then be employed. "All craftspersons are designers. But all designers are not craftspersons," a Shilp Guru says, and his audience responds with spontaneous applause. Few would dispute the aesthetic value of traditional work. We can perceive in it a sort of living quality, though we might not easily define what that is. New work, while appropriate to the new market, does not have that elusive living quality. It lacks the integrity of cultural expression, or the spirit of the artisan. Those honored artisans, Master Craftsmen and Shilp Gurus, express frustration at current trends. A shilp Guru holds up a golden box he made. "Look at this," he says. "This is beautiful." And it is. "They tell us to make it cheaper, faster..." "That's not what we do!" echo the Salvis, the last artisans of patolu weaving. It is when the art of tradition-based work is lost that the tradition is endangered. Surely, design input is needed for new markets. Neither the concern for this problem nor the schemes are wrong. But the approach to the problem needs to be altered. Designers must learn to think like artisans, someone suggested. But the real problem is that no one wants to be a laborer. If we want craft to flourish, we first have to attend the artisan. Craft must be re-integrated and the artisan must be significantly involved in both design and craft aspects. CREATIVITY AND DESIGN IN A LIVING TRADITION When artisans are engaged in finding their own solutions to problems, they find the satisfaction of creativity. If we examine an example of a living tradition, that of textile arts of the Kachhi Rabaris of Kutch, we find that artisans have not only ability but great interest in the creative aspect of their craft. The women of this nomadic community in the process of settling have had to enter the world of cash economy as income from traditional sources ceased to be adequate for survival. Whether earning by manual labour or through their traditional embroidery skills, Rabari women now face the dilemma of multiple demands on limited time. At the same time, requirements for traditional embroidery for dowry have increased. Unmarried girls, put into conflict, have responded by learning to balance and prioritize. For their traditional work, they have begun to use time savers such as machine embroidery, ready-made rick rack and ribbons. The minimization of labour in traditional art has allowed entry of new elements. With exposure to new markets through settling and embroidering commercially, Rabari women have gained access to a vast array of new materials, colours and patterns. Remarkably, Rabaris choose new elements according to their own, still vital sense of aesthetics-- essentially following the design brief. The labor savers expressly enable more rapid execution. As a result, artisans have become eager for ever rapid changes in style which are no longer subtle variations of pattern within a pati, but entire revamping of the concept of a piece. Thus, fashion has emerged as a concept. In new Rabari traditions, while innovation and fashion do not draw on the commercial work from which women may be earning, the pace and extent of innovation have followed the development of wider markets. In embracing fashion, artisans have not only demonstrated their ability to innovate but- more important- their capacity to do so quickly and more radically. Another aspect of new traditions worth noting is that bad habits of commercial craftsmanship have not crept in. Women welcome time saving devices, but not compromises in craftsmanship. Within the community, fine skill and sensibility are still a matter of personal worth. By focusing on the labour aspect of embroidery, and eliminating some of the tedium of hand work, Rabari women have not only enabled their traditions to remain economically viable. They have also shifted the focus of creativity. Different skills have become important in new fashion-traditions: choosing from the array of available materials, conceptualizing patterns. Witness the innovation of Monghiben on the traditional ludi, the identifying woolen veil. Monghi wanted to excel in displaying her creative skills on her wedding ludi. Yet she knew that she would wear it only for a few hours. In any case, if she wore it more often, her efforts would be lost in wear and tear. Defining the problem, she devised an ingenious solution: showcase bands elaborately worked with machine and hand embroidery, which she attached to the borders of her veil. The bands could then be reused by her younger sister or, if no longer in fashion, double as a toran. The new styles in fact allow women to focus on design rather than execution. Most noteworthy, Rabari women enjoy the designing aspect of the new traditional work. Monghi has become a celebrity and an inspiration to her peers. AN ARTISAN CENTERED APPROACH The question then is can artisans apply their ability to innovate toward making art appropriate for the current market? If they gain the same skills and knowledge as professional designers, and learn to access their market, can they solve their own design problems? Could they find appropriate solutions for the persistent problem of cost vs. fair wages, and nurture the critical element of cultural expression? What if artisans learn to think like designers! If one recognizes the creative capability of artisans, in terms of cost efficiency and feasibility it is more practical to think of training traditional artisans in design principles than to train designers in craft traditions. Further, in terms of the survival of craft traditions, it is far more sustainable. Encouraged by working collaboratively with artisans in design, Kala Raksha is planning an institution to address the issue of craft design in a new way. Kala Raksha Vidyalaya is envisioned as an educational institution specifically for artisans of Kutch. Traditional artisans rarely gain access to contemporary formal design training due to social and financial barriers. The institution envisioned will differ from others primarily in that its environment, curriculum and methodology will be designed to be appropriate for adult artisans with a vast existing body of traditional knowledge, who are currently working in their field. Master artisans will participate in developing the institution, to insure that these goals are met. Personalization is a critical and powerful element in effective education. The Vidyalaya will thus address the issues of relevant education and self confidence while building the capacity to design for new markets. To facilitate the shift of market, and relationship to the new market, Kala Raksha Vidyalaya will address and interlink three broad areas: thorough understanding of traditional crafts, contemporary design input, and access to markets. UNDERSTANDING TRADITIONAL CRAFTS Traditional artisans have an incomparable fortune in the deep knowledge and hereditary skills of their craft. Imbibed from childhood as an inextricable part of a way of life, both knowledge and skills are almost involuntary. Yet, like breathing, craft knowledge and skills may not be consciously attended. The Vidyalaya will guide artisans to examine their own traditions, and others. Study and reflection will enable them to most effectively access their body of existing knowledge. Drawing on experiences with the Kala Raksha Folk Art Museum and Resource Center, the course will include documentation, presentation, and study of traditions. Artisans will learn to observe, record, use, and above all appreciate their known traditions in a conscious way. DESIGN Self confidence in the ability to solve problems is the most important and enduring benefit of education. Contemporary design, the major course of Kala Raksha Vidyalaya, will focus on a conscious approach to design principles and problem solving. Artisans will gain conscious knowledge and learn skills relating to design, which they will apply in authentic situations in their respective media. Technical assistance will be provided as needed, but with focus on understanding the limitations and possibilities of technology. Artisans will learn to use technology to expand their scope, rather than feel circumscribed within its limitations. As artisans of Kala Raksha noted, "We need to learn what is new, what we don't already know." "Embroidery is what we do," one woman explained. "Education is different; education is essential." With the wealth and depth of traditional knowledge, artisans will be able to quickly absorb and utilize design related information. Artisans' experiences confirm the profound utility of design education. Ismail Mohammed Khatri, a block print and dye master of Dhamadka and Advisory Board member of Kala Raksha Vidyalaya, relates how as a young boy he was skilled in making wooden blocks. With indigenous tools and methods he could innovate within existing patterns. Then a young designer from NID gave him a compass and showed him how to make a perfect square. From that simple, appropriate technology, he says, he knew he could create infinite new patterns for the rest of his life. In a recent project for the Manly Art Gallery and Museum in Australia, artisans were asked simply to express their experiences of the massive earthquake that devastated Kutch in January 2001. The same senior artisan who had given up confidence when her patchwork cushion cover went into the reject pile created an incredibly complex and vibrant work, including innovative three dimensional techniques. In this case, she was able to extend beyond her capacity simply with encouragement and protected space to explore --rarely found in the work-driven daily life. And after completing the piece, she was eager for the opportunity to do further expressive work. In a concerted effort to bridge the digital divide, new technology will be an important component of the artisan design school. Using new technology as an extension of existing knowledge will enable quick acceptance of the medium itself, encourage artisans to think in new ways, and help them to access new markets. After a first encounter with computer aided design at an education workshop at Jiva School, a young Rabari artisan enthusiastically exclaimed, "A week ago we didn't know what a computer was, and today we can use it to make designs!" ACCESS TO MARKETS Access to new markets is the critical issue, and will prove the ultimate success of the Vidyalaya's education. Artisans want results, Ismail Khatri emphasizes. The only motivator for working artisans is improved income. Understanding the market must drive design innovation. Exposure to target markets will be essential. Why is Ismail more successful than most of his traditional community? The design training he has enjoyed, aptitude to learn, but also exposure. Ismail has been able to establish direct links to his customers. "We learn to understand what they want; we get the courage to experiment," he explains. "After that, it has its own perpetual motion." In this component of education, exposure to markets will be insured in two way interaction: artisans will go out and clients will come in. Professionalism will be encouraged to facilitate the interaction. And to bridge the existing cultural gap, artisans will also learn to access resources, so that they can solve future problems. For this, information technology offers great potential to artisans as a means of overcoming social and physical barriers to markets which can appreciate and afford their work at fair prices. Not every graduate of Kala Raksha Vidyalaya will become a local designer, just as not every college graduate becomes a professor. Nor will the institute obviate the need for professional designers from outside the artisan community. But the education of the Vidyalaya will change the working relationship between graduates and other designers to be more egalitarian. The education experienced will be relevant to the artisan's life. It will enable him or her to be more capable and confident in work, and in operating in a world beyond the familiar village setting. And hopefully it will enable artisans to value education and encourage it in their families. By engaging the contemporary world through relevant design education, artisans can re-integrate their art, and revitalize its spirit so that it expresses a whole, new world. FURTHER READING Frater, Judy "Traditional Art in the Eye of the Artisan: Changing Concepts of Art, Craft and Self in Kutch," Seminar 523, March 2003. New Delhi. "Contemporary Embroideries of Rabaris of Kutch: Economic and Cultural Viability," Textile Society of America Proceedings, 2002. "This is Ours:' Rabari Tradition and Identity in a Changing World," forthcoming in Nomadic Peoples "Rabari Embroidery: Chronicle of Tradition and Identity in a Changing World," forthcoming in a Crafts Council of India publication 1999 "When Parrots Transform to Bikes: Social Change Reflected in Rabari Embroidery Motifs," Nomadic Peoples (NS) Vol. 3, issue 1. 1995 Threads of Identity: Embroidery and Adornment of the Nomadic Rabaris. Ahmedabad: Mapin. Kak, Krishen, "Integrating Crafts and the Educational System," paper presented at the Crafts Council of India/ Development Commissioner for Handicrafts/ Export Promotion Couoncil for Handicrafts International Seminar on "Crafts, Craftspersons and Sustainable Development," New Delhi, November 16-18, 2002 Rudolph, Steven- personal communication. See also http/www.Jiva.org Tyabji, Lalia, ed. "Celebrating Craft," Seminar 523, March 2003. New Delhi

* to be published in Handmade in India, a National Institute of Design Publication

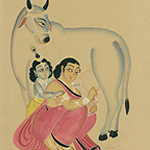

An ancient one and the artists who create them are known as Patua. This tradition features long vertical multi paneled scrolls known as patas (paintings) or jorana patas (rolled paintings) since the scrolls are rolled up for storage and transportation. Each panel represents a particular sequence in the story and as they are unrolled for viewing, the accompanying couplet or story is recited. Painted on sheets of paper glued at the edges to form one continuous roll, these scrolls are mounted on cloth (usually old saris) for greater strength and flexibility. Traditionally, the performer would carry these scrolls from door to door, and depending on people’s request, particular stories would be narrated for a small fee, either in cash or kind. In 1983, at the age of 21, Kalam held the first show of his works. Soon, Kalam achieved great renown for his finely detailed works, exhibiting his patachitrapaintings at the West Bengal Pavilion, India International Trade Fair, Delhi in 1987, 1988 and 1989. His scrolls on the French Revolution done for the French Cultural Centre in Kolkata were hailed as a new innovation in patachitra art and he collaborated on shows with artists from other countries. Once he mastered patachitra painting, Kalam focused his attention on yet another Bengali art tradition, namely Kalighat paintings. At first, he was inspired by the paintings of yore and then later developing his own individual repertoire of contemporary Kalighat paintings. Kalighat paintings are believed to have originated in the nineteenth century with the establishment of the Kali temple in the city of Kolkata. Initially developed as religious souvenirs for pilgrims coming to the temple, Kalighat paintings of gods and goddesses were rendered quickly by artists sitting outside the temple. Using water-colours and cheap mill made paper, the artists executed drawings as per the buyer’s request for a small fee. Typically, Kalighatpaintings are not overly embellished or crammed with imagery as in many other folk art styles such as Madhubani or Pabuji phads or Puri paintings. Rather, Kalighatpaintings display a minimalist yet striking treatment of subject matter. Gradually, secular themes began to be introduced and Kalighat paintings became a means of social commentary. When Kalam Patua began making Kalighat paintings, the tradition had all but died out, replaced successively by cheaper wood-prints and then machine printed images. He began by learning from existing works, painstakingly copying the pieces till he mastered the art. It was not easy as he had a full-time job in the post-office but soon, reviving Kalighat art became a passion. Once he became confident of his brush-strokes, he began experimenting with themes, coming up with truly original interpretations of contemporary events and world-views. Kalam has participated in several shows including the The Margi & The Desi curated by Dr. Alka Pandey at Lalit Kala Academy, New Delhi, (2004); Bouro-64, along with a group of artist from Switzerland at the Birla Academy Of Art, Kolkata, (1996); and a two-man show along with a German artist organized by Poliphony, a group of employees at Alliance Française, Kolkata, 1994. In 2002, he was invited by the Canadian Museum Of Civilization to demonstrate his art in Canada. In 2003, Dr Jyotindra Jain curated a solo show by Kalam at Gallery Espace, New Delhi. His works are part of the permanent collection of National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi and in several private collections in India and abroad. Kalam’s works never fail to delight – the bold lines and soft swathes of colour, the fine detailing and bare background, creating sheer visual beauty. One can look at his works a million times and always find something to delight in.

I was born on August 15, 1967 in a poor handloom family located at Srikalahasti town. Since my childhood, I have been fascinated with line drawings on the slate and making clay toys. Understanding my interest in the art, my father enrolled me in Kalamkari art classes in my 12th year under Late Sri S. Rambhoji Naik, (National Awardee) who was also working as a technical assistant in Government Kalamkari training centre, Srikalahasti. I learnt the art alongside continuing my school education. I trained for nearly 10 years from my kalamkari teacher besides my higher education. During the period of training I got lot of exposure in making different shades of natural colours using plants, leaves and flowers. I work mainly with natural dyes on cotton cloth.

Although Kalamkari art is an ancient Indian traditional painting, particularly related to the Hindu mythology, I have also made number of paintings on the other themes such as Buddha, Jesus Christ and everday life in our village. For the first time, in the Kalamkari art field, I have drawn very small size figures (5 cms in height) with a bamboo stick pen (Kalam). For this type of miniature painting (Sampoorna Ramayan), I was awarded the prestigious ‘National Award’ for the year 1992 from the Honorable President of India. I got special notice for my paintings ‘Weaving woman’ and ‘Farmer in the field’ which highlighted the plight of poor handloom and farmer families. I have illustrated “Mangoes and Bananas” by Nathan kumar Scott, Tara publishers, Chennai and “How to learn Kalamkari” (awaiting publication).

Although Kalamkari art is an ancient Indian traditional painting, particularly related to the Hindu mythology, I have also made number of paintings on the other themes such as Buddha, Jesus Christ and everday life in our village. For the first time, in the Kalamkari art field, I have drawn very small size figures (5 cms in height) with a bamboo stick pen (Kalam). For this type of miniature painting (Sampoorna Ramayan), I was awarded the prestigious ‘National Award’ for the year 1992 from the Honorable President of India. I got special notice for my paintings ‘Weaving woman’ and ‘Farmer in the field’ which highlighted the plight of poor handloom and farmer families. I have illustrated “Mangoes and Bananas” by Nathan kumar Scott, Tara publishers, Chennai and “How to learn Kalamkari” (awaiting publication).

I have also had special exposure on temple architecture. I have visited important ancient temples likeTanjore, Madurai, Kanchi, Trichy, etc. which are famous for sculptures of Hindu mythology, to study and understand the different styles of idols. In addition to kalamkari, I have made many cement sculptures for temple decoration. After the death of my art teacher in 1989, I have been continuing this art by giving free training to a large number of students at Srikalahasti town, Chittoor district. So far I have trained eight students.

I have also had special exposure on temple architecture. I have visited important ancient temples likeTanjore, Madurai, Kanchi, Trichy, etc. which are famous for sculptures of Hindu mythology, to study and understand the different styles of idols. In addition to kalamkari, I have made many cement sculptures for temple decoration. After the death of my art teacher in 1989, I have been continuing this art by giving free training to a large number of students at Srikalahasti town, Chittoor district. So far I have trained eight students.

Founder of Kalamkari Hastha Kala Kendram (Regd. No. 229 dt 1997):

Kalamkari hastha kala kendram (Before registration it was Sri Rambhoji Naik kalamkari Kala Kendram) was started in 1989 in memory of late Shri Rambhoji Naik, National Awardee in Kalamkari and also my kalamkari art teacher. This is one of the small organizations promoting and identifying traditional arts and artisans for their improvement. Since 1989, every year on August 31st we celebrate its Anniversary. As a part of this annual ceremony, we conduct drawing competition to students (From LKG to Bachelor degree students) and also felicitate the traditional artisans who have not gained much recognition. Since beginning I have been serving as a General Secretary for this organization.

Founder of Kalamkari Hastha Kala Kendram (Regd. No. 229 dt 1997):

Kalamkari hastha kala kendram (Before registration it was Sri Rambhoji Naik kalamkari Kala Kendram) was started in 1989 in memory of late Shri Rambhoji Naik, National Awardee in Kalamkari and also my kalamkari art teacher. This is one of the small organizations promoting and identifying traditional arts and artisans for their improvement. Since 1989, every year on August 31st we celebrate its Anniversary. As a part of this annual ceremony, we conduct drawing competition to students (From LKG to Bachelor degree students) and also felicitate the traditional artisans who have not gained much recognition. Since beginning I have been serving as a General Secretary for this organization.

Work in Museum Collection:

Work in Museum Collection:

- Madras Craft Museum(Craft Foundation): Sampoorna Ramayanam miniature painting (2.00X1.30 Meter), which was selected for National Award in 1992.

- The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, UK: One large kalamkari painting (5.00 x 2.60 Meters) namely “Sampoorna Ramayanam” (which was selected for ‘Mahatma Gandhi Birth Centenary Memorial award’ in 1993, from Victoria Technical Institute, Chennai) was purchased by the Ashmolean Museum (Eastern Arts section).

- Shilpa kala vedika, Shilparamam, Hyderabad: For the first time, in the kalamkari art field, a major kalamkari panel work around 150 running meters prepared. The painting was made on silk cloth using natural dyes and all the figures related to rural and traditional musicians (not mythological pictures).

- Handicraft emporiumssuch as Victoria Technical Institute, Chennai, Andhra Pradesh Handicrafts Development Corporation, Kalanjali, Contemporary Arts & Crafts, Hyderabd; Kaveri, Dastkar, Craft Council of India, Craft council of Andhrapradesh, etc. have collected my work.

Awards Received:

Awards Received:

- Mahatma Gandhi Birth Centenary Memorial Awardin 1986 from Victoria Technical Institute (VTI), Madras for Sri Rama Pattabhisekham Painting.

- Mahatma Gandhi Birth Centenary Memorial Awardsecond time in 1990 from Victoria Technical Institute (VTI), Madras for Sri Sita Rama Charitra Painting.

- Mahatma Gandhi Birth Centenary Memorial Awardthird time in 1993 from Victoria Technical Institute (VTI), Madras for Sampoorna Ramayanam Painting.

- National Award(Govt. of India) in 1994 from Honourable President of India at New Delhi for Sampoorna Ramayan Painting.

- Outstanding Young Person Awardin 1994 from the Junior Chamber, Tirupati, India.

- Exhibition and Demonstration at National Level Exhibition Taj Festival 1993, Agra conducted by the Ministry of Textiles, Govt.of India.

- Kalamkari art demonstration at Surajkund Mela – 95, New Delhi conducted by Govt.of India.

- Exhibition & Demonstration at International Art Festival (Art in Action), Oxford, UK during the period of 13 – 16, July 1995 13 – 16, July 1996 15 – 18, July 1998 18 – 21, July 2002

- Exhibition & Demonstration at Nehru Centre, London, UKduring the period of 23-25, July 2002

- Exhibition & Demonstration at UNESCO, Toulouse, FranceSponsored by CIES, France in 1996

- Exhibition at FIAS, Institute of Aeronatique, Toulouse, France in 1996

- Participation in National Award winners Exhibition in 2001at Shilparamam, Hyderabad