JOURNAL ARCHIVE

|

Issue #002, Monsoon, 2019 ISSN: 2581- 9410 Introduction |

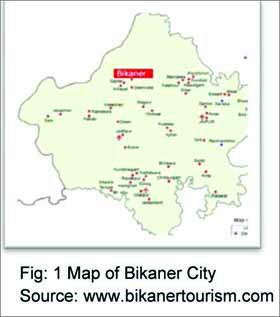

| Location of Nagasar

|

|

People of Napasar Population As per the population of India website (2014), the total population of Napasar is 19500, out of which 10101 are males and the rest 9399 are females. Most of the population of Napasar belongs to Brahman and Baniya castes. This village is small and is divided in different mohallas like Uttaradwas, Goyalon ka Mohalla and Deshnok roads. The major percentages of weavers and spinners are residing in these sections of the village |

|

Literacy Most of the men of the village have acquired education till middle school and there are very few of men who have done senior secondary or are doing graduation. On the other hand most of the women of older ages are completely uneducated, while there are also women of younger ages who are educated till senior secondary levels. The research revealed that the aim of acquiring education is becoming essential with the younger generation be it male or females. |

|

Profession

Napasar is a place of semi arid zone, where farming is done only for three to four months in a year. Therefore most of the people are dependent on textile industry for earning their livelihood. Khadi Gram Udyog and few other khadi institutions are providing job to spinners and weavers in the village. Most of the women of this village are hand spinners and they are either helping their family profession or are working as freelance spinners for different organizations or persons.

|

|

Napasar Hathkargha Vikas Samiti

In this slow and poor condition of weaving profession, there is still a hope for many weavers by a cluster called as Napasar Hathkargha Vikas Samiti. This samiti is a group of weavers working together under one roof in a workshop located at Deshnok road.

The cluster workshop was started by the aid of Rangsutra, an NGO headed by Ms. Sumita Ghose based in Delhi with its branches at Banaras and Bikaner. This cluster is presently, serving to the fabric demands of Rangsutra and few other small organizations like Maandana a fashion boutique from Bikaner. Tulsiram ji is a proficient and sample weaver of the cluster. He guides and trains other weavers working in the cluster workshop. He along with Om ji takes care of all the production orders. His career of weaving is more than forty years, and he is among the few who remembers about the age old techniques of fabric production and its raw materials at Napasar. Currently the cluster has 9 weavers on the list, and the number keeps increasing and decreasing depending on the amount of work with the cluster. The fabric production in the workshop is of mainly 100% cotton fabric in various densities and weights. The fabric is mainly used in apparels. There are about 7 big width looms and two small widths loom, with one sample loom created by Tulsiram ji. The cluster is developing fabrics for kurtas, waistcoats and lowers both for males and females. There are few more younger weavers in the cluster like:

Govardhan, who is a young weaver attached with the cluster since past few years. He is trained by his forefathers to weave. He intends to carry weaving as his profession for income generation. Ashok is the son of Tulsiram ji and is a young weaver. He has inherited the weaving craft from his father and forefathers. He also works independently as freelance weaver for other organizations along with the cluster.

Ramesh is the youngest weaver among all. He is just 19 years old and he hasn’t inherited the craft from his father or forefathers. He has learnt the craft of weaving at the cluster from Omji and Tulsiram ji. He doesn’t have loom at home, so he is completely involved with the cluster work. |

|

Handloom fabrics of Napasar

Weavers outside Napasar Hathkargha Vikas Samiti are creating woolen shawls and aasans given by Khadi Gram Udyogs or Pratisthans. This is a place where earlier double cloth fabrics were made of camel hair which were used as floor coverings. Also the double cloth technique was utilized in making large width carpets on smaller width looms. However with the elapse of time, the craft of making double cloth is lost and usage of camel hair as fibers is forgotten. Reason being that currently most of the homes at Napasar have replaced camels by transportation mediums like cars, bikes and cycles, which in turn have reduced the number of camels in the village. This has negatively affected all the crafts and products associated with the camels. The Napasar Hathkargha Vikas Samiti is trying to revive one such forgotten craft of its traditional weaving along with generating income sources for their weavers in its village. The cluster wants to give an identity to its village and its craft in local, national and international markets with quality products and designs. |

|

References http/www.bikanertourism.com http/www.weather-forecast.com http/www.msmedijaipur.gov.in/dips_bikaner.pdf http/www.napasar.info/home/History http/www.populationofindia.co.in/rajasthan/bikaner/bikaner/.napasar http/www.napasarweaves.com |

Issue #008, 2021 ISSN: 2581- 9410 Traditional craftsmanship is perhaps the most tangible manifestation of intangible cultural heritage. And it finds many varied ways to manifest in our daily lives – in the form of tools, decorative art, ritual objects, musical instruments, toys, household utensils, jewellery, costumes, textiles, traditional architecture and much more. Globalization, industrialization and consumerism has posed significant threat to the survival of these traditional forms of craftsmanship, like other forms of intangible cultural heritage. Over the past centuries, much of our Cultural Heritage has been irretrievably lost. We have witnessed and continue to witness the destruction and deterioration of these irreplaceable treasures. Other underlying causes of this prolonged and continuing tragedy are ignorance, indifference, lack of care and lack of appreciation. Since a significant part of our unique cultural heritage is retained in handicrafts, architecture and traditions, this heritage needs to be identified and protected or it may disappear forever. Thus, several cultural heritage experts have highlighted the need for safeguarding our traditional crafts not only to keep the community’s identity but also to give economic advantage and other values. Let’s understand what are these other values associated with Craft Heritage. It expresses a sense of community and ethnicity. Because craft is an expression of culture which conveys the spirit of the people who created them, it can help young people to acquire inter- and intra- cultural understanding and invite cross-cultural communication. Understanding one’s Cultural heritage teaches openness towards those who are different from each other. By putting people in touch with our own and other people's feelings, the culture/heritage mapping teaches one of the great civilizing capacities – how to be empathetic. It has the enormous power to join people of different backgrounds. Together people can discuss the shared symbols of their collective memory and consequently work together to rebuild their own identities. Accepting cultural diversity and its understanding helps develop mutual respect and renewed dialogue amongst different cultures In this sense cultural heritage also plays a vital role in the democratization process. Not so long-ago policy makers recognized that culture is imperative to any country in development, be it rich or poor. And that craft heritage can make a valuable contribution to conflict resolution as well. Since culture is ever evolving - resulting from a constant selection process for both cultural and political reasons, an understanding of this also gives a sense of what we have lost and what we have retained from the past (both tangible and intangible) – and hence what to retain consciously for the next generations. The future of our remaining craft heritage will depend largely on the decisions and actions of the present generation of young people who will soon become the leaders and decision-makers of tomorrow. In the above context, teaching about cultural heritage in schools becomes very crucial. Education at all stages has been regarded as a powerful instrument for social transformation. One of the major tasks of education in India today is to usher in a democratic, socialistic, secular society which removes prejudices among people. The objective of bringing in our Craft Heritage in schools is to help in the realization of these goals. Craft Heritage Education, therefore, in schools advocates the reaffirmation of identity, mutual respect, dialogue, unity in diversity, solidarity and a positive interaction among the cultures of the world. This issue presents views and essays on the above topic, by experts in the field. Ashoke Chatterjee writes about the quest, the purpose and the relevance of Craft Education in schools in India, learning from past experiences and preparing for the future.

MP Ranjan has written about encouraging the development of fine craftsmanship capabilities across the entire Indian population to make India a creative economy of the future. The paper outlines ways in which new education for the creative economy can leverage the living resources of the Indian craft traditions to build a better and more rooted curriculum of the future for all students that is a vehicle for nurturing the creative traditions that India has been best known for, in the past.

I would like to thank Aditi Ranjan and NID Ahmedabad to allow us to republish MP Ranjan’s article in our issue.

Geetanjali Krishna writes about Shamsheer Ali, a Naqsha artist from village Khamaria in Uttar Pradesh and how he has altered the landscape of his community through his teaching skills, where craft remains tightly intertwined with people’s daily lives and livelihoods. Khyati Vinod and Shinjini present a case study of Khamir’s craft integrated curriculums for local schools in Bhuj, and the learnings from the same. With artisans extending their role from craft producers to cultural practitioners and teachers, this article relooks at the age-old debate between a literate individual versus an educated individual. Aruj Khaleeq, an interdisciplinary educationist from Pakistan who has been associated with educational leadership shares the perspectives of Educationists from Pakistan on inclusion of Craft Heritage in schools in Pakistan. Iti Saanchie Goswamy, a young design student explores the IT capital of India, Bengaluru to see how the traditional crafts people living in Bengaluru make best of the two worlds that coexist; understand their challenges to safeguard their traditional practices in a Globalized World of machines and technology; and compare the modern vis-à-vis the traditional ways of learning and passing on the knowledge, through a beautiful narrative of her personal experiences. It has been a pleasure to put together this issue for Ritu Sethi and Craft Revical Trust. I thank Ritu and Ahmad for their patience through the whole process especially the numerous delays due to Covid. I would also like to thank all the experts for their time and contributions. It's been a very fulfilling experience indeed. Hope you enjoy reading through the articles.Issue #006, Autumn, 2020 ISSN: 2581- 9410 This article describes an income-earning initiative for rural Maya artisans that my 3 colleagues and I established in Guatemala in 2009. We introduced a non-traditional craft, called rug hooking, and we created a design curriculum where literacy and numeracy were not a prerequisite for participation. About a year after introducing the craft, sensing the economic potential of hooked rugs to transform their livelihoods, we trained 9 of the rug makers as design teachers who in turn, trained more women. Within five years nearly 60 women were hooking rugs. My colleagues and I formed a legal Guatemalan non-profit called Multicolores. Our mission is to expand opportunities for our artisan members. Notably:

- Within 5 years of the first rug making class, in 2014 Multicolores was accepted to the International Folk Art Market in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the world’s most rigorously juried folk art event.

- Within six years of the first rug making class, in 2015 the women were recognized by the Alliance for Artisan Enterprise, a global competition sponsored by the Aspen Institute and US State Department to bring attention to the Craft Sector of the global economy, 65% of which is created by women.

- In 2019, ten years after the first rug making class, the International Folk Art Market bestowed one of six Community Impact Awards upon Multicolores in recognition of the economic impact of rug money upon the communities where the artisans reside.

Huipil (women’s blouse hand woven on a backstrap loom) from Chichicastenango.

Photo Credit: David Husom

While in Guatemala I met several dedicated women leading small artisan non-profits. They worked to create income-earning opportunities for rural Maya artisans marginalized by their paternalistic society through systemic poverty, racism, and more. I tried –without success- to reconcile the artisan’s poverty with their extraordinary textile accomplishments. The artisans weave complex and sophisticated cloth on backstrap looms- a loom that, after-all, is nothing more then a collection of sticks and threads. Yet, for many artisans, in spite of their weaving proficiency access to opportunity is denied and relentless poverty is a pervasive fact of life.

In order to remain competitive in the global market place, I knew these non-profit groups were continually interested in expanding their textile repertoire. And so Jody, an accomplished weaver, good friend and traveling companion and I offered to teach a weekend-long workshop on how-to-hook rugs. I reasoned that rug hooking, like back strap weaving, is a portable technique and therefore might appeal to the women. “Paca,” or recycled clothing would provide a readily available and affordable source of rug materials. (Paca arrives in Guatemala from the US by the bale: it’s a thriving industry.) Jody’s and my class was to teach the technique and then let our non-profit host, Oxlajuj Batz’ take it from there.

Huipil (women’s blouse hand woven on a backstrap loom) from Chichicastenango.

Photo Credit: David Husom

While in Guatemala I met several dedicated women leading small artisan non-profits. They worked to create income-earning opportunities for rural Maya artisans marginalized by their paternalistic society through systemic poverty, racism, and more. I tried –without success- to reconcile the artisan’s poverty with their extraordinary textile accomplishments. The artisans weave complex and sophisticated cloth on backstrap looms- a loom that, after-all, is nothing more then a collection of sticks and threads. Yet, for many artisans, in spite of their weaving proficiency access to opportunity is denied and relentless poverty is a pervasive fact of life.

In order to remain competitive in the global market place, I knew these non-profit groups were continually interested in expanding their textile repertoire. And so Jody, an accomplished weaver, good friend and traveling companion and I offered to teach a weekend-long workshop on how-to-hook rugs. I reasoned that rug hooking, like back strap weaving, is a portable technique and therefore might appeal to the women. “Paca,” or recycled clothing would provide a readily available and affordable source of rug materials. (Paca arrives in Guatemala from the US by the bale: it’s a thriving industry.) Jody’s and my class was to teach the technique and then let our non-profit host, Oxlajuj Batz’ take it from there.

Picking through piles of ‘paca’ for suitable rug material

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Picking through piles of ‘paca’ for suitable rug material

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Paca store.

Photo Credit: Mary Littrell

After the first class I began to understand that non-profits often did not possess the funds or capacity to fully explore the potential of a new craft like rug hooking. However, as a professional textile artist and design teacher, along with my knowledge of the US market, I had an inkling of the crafts potential in a way the non-profit leaders did not. When asked to teach a second workshop I readily agreed with one proviso: each participant would create her own design and the designs would be informed by the women’s traje.

Rug hooking is not a traditional craft- but by drawing inspiration from their extraordinary textile heritage- their cultural property- their rug designs, I reasoned, might stand out on the global stage. They could reinterpret tiny brocaded or embroidered elements of traje to create large-scale rug designs that speak of Maya heritage and culture.

Paca store.

Photo Credit: Mary Littrell

After the first class I began to understand that non-profits often did not possess the funds or capacity to fully explore the potential of a new craft like rug hooking. However, as a professional textile artist and design teacher, along with my knowledge of the US market, I had an inkling of the crafts potential in a way the non-profit leaders did not. When asked to teach a second workshop I readily agreed with one proviso: each participant would create her own design and the designs would be informed by the women’s traje.

Rug hooking is not a traditional craft- but by drawing inspiration from their extraordinary textile heritage- their cultural property- their rug designs, I reasoned, might stand out on the global stage. They could reinterpret tiny brocaded or embroidered elements of traje to create large-scale rug designs that speak of Maya heritage and culture.

Drawing a rug design at scale with inspiration from traje

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Drawing a rug design at scale with inspiration from traje

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

woman’s hand woven brocaded huipil (blouse) from Chajul, Guatemala.

Photo Credit: David Husom

Working as a dedicated team, Jody and I connected with Reyna Pretzantzin and Cheryl Conway Daly to establish a legal Guatemalan non-profit called Multicolores. All of us had glimpsed the potential for this technique as a possible economic game-changer for the rug makers. Now, by forming our own Guatemalan based non-profit we could freely explore the craft’s potential. Cheryl and Reyna would run the organization from Guatemala. In between our quarterly trips to Guatemala Jody and I would ply our networks in the US for support and more. In Guatemala, Multicolores would purchase the women’s rugs outright, not on consignment. In the US Jody and I would conduct rug sales. Proceeds would be returned to Multicolores.

Reyna, a professional Maya woman with a background in business and craft production and I worked closely as a teaching team. Her understanding of the women’s skill sets and cultural mores were indispensible: she knew when to push the students harder- and when to pull back.

Next was to coalesce the class around a list of six design principles. These principles conveyed, I thought, the most essential design concepts to create compelling works. The students, ages 15-48 years old, with zero-6 years of formal schooling, were tasked with creating icons to represent each principle. For the non-literate students, the icons made for familiar reference.

Design Principles:

woman’s hand woven brocaded huipil (blouse) from Chajul, Guatemala.

Photo Credit: David Husom

Working as a dedicated team, Jody and I connected with Reyna Pretzantzin and Cheryl Conway Daly to establish a legal Guatemalan non-profit called Multicolores. All of us had glimpsed the potential for this technique as a possible economic game-changer for the rug makers. Now, by forming our own Guatemalan based non-profit we could freely explore the craft’s potential. Cheryl and Reyna would run the organization from Guatemala. In between our quarterly trips to Guatemala Jody and I would ply our networks in the US for support and more. In Guatemala, Multicolores would purchase the women’s rugs outright, not on consignment. In the US Jody and I would conduct rug sales. Proceeds would be returned to Multicolores.

Reyna, a professional Maya woman with a background in business and craft production and I worked closely as a teaching team. Her understanding of the women’s skill sets and cultural mores were indispensible: she knew when to push the students harder- and when to pull back.

Next was to coalesce the class around a list of six design principles. These principles conveyed, I thought, the most essential design concepts to create compelling works. The students, ages 15-48 years old, with zero-6 years of formal schooling, were tasked with creating icons to represent each principle. For the non-literate students, the icons made for familiar reference.

Design Principles:

The design principles taped to the classroom wall.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

The design principles taped to the classroom wall.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

- Derive design inspiration from traje.

- Avoid common (trite) imagery, imagery such as hearts and houses that could originate from any culture anywhere.

- Combining figurative and geometric imagery is Ok.

- Vary the scale of your design elements.

- Infuse your design with vitality. The diamond on the left is plain; by adding additional elements to the diamond you create energy.

- The rug’s border should be proportionate to the rug’s dimensions.

Buddying up to role-play teacher-student.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

For many of the students the use of templates is a familiar practice, although with a far different application then we were using in our class. Easter is the most popular celebration in Guatemala. At Easter time, by day, religious societies and neighborhood organizations create elaborate temporary ‘street rugs’ to be admired by the community. The street rugs are made with flower petals, pine needles, colored sawdust, and other biodegradable materials. Templates cut from sheets of plywood help guide the creation of the designs. Then, by evening, religious processions along with marching bands parade through the streets destroying the temporary rugs.

Buddying up to role-play teacher-student.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

For many of the students the use of templates is a familiar practice, although with a far different application then we were using in our class. Easter is the most popular celebration in Guatemala. At Easter time, by day, religious societies and neighborhood organizations create elaborate temporary ‘street rugs’ to be admired by the community. The street rugs are made with flower petals, pine needles, colored sawdust, and other biodegradable materials. Templates cut from sheets of plywood help guide the creation of the designs. Then, by evening, religious processions along with marching bands parade through the streets destroying the temporary rugs.

Semana Santa template.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Semana Santa template.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Colored sawdust used to create a Semana Santa street rug.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Over an eighteen month long period I travelled to Guatemala quarterly to conduct workshops. From one workshop to the next Reyna and I built on sequential skill sets. In between workshops, Reyna provided follow-up, ensuring the women comprehended and implemented the workshop’s object lessons. The women would travel to our small office, some traveling from homes located four hours and many bus transfers away, to deliver rugs and receive payment. At the office, they would be welcomed with a snack and then Reyna would offer feedback, sometimes requiring the artist to change her design on the spot to comply with the design criterion before getting paid.

Other times Cheryl and Reyna travelled these same long routes to visit the rug makers in their remote villages. The two checked on production progress and also followed up with the artists-as-design-teachers to determine how the transfer of information was proceeding. Cheryl gathered baseline empirical data (number of people living in the dwelling, how many children lived in the dwelling and more). They also noted if the home had electricity or if there was a table and chair for the artisan to work upon- or- did the artist work at rug making while propped upon the family bed? It was during these community visits that seeds for Multicolores’ social programs were planted. (Multicolores now offers social services to our artisan members. The services require a measure of co-payment from the artists; we do not believe in ‘hand outs.’ Services include a program to buy furniture and lighting for the artist’s workplace, a family-wide health insurance plan and more.)

One day Yolanda, an accomplished traje weaver with an entrepreneurial spirit, whose rugs were consistently among the first to sell in any collection, complained to Reyna about the wages paid. She believed her rugs were a higher value then others because her rugs were more detailed and she did not think it fair that she was paid the same price as everyone else. She was right. A class discussion ensued about critiquing each rug. It was important to agree upon criteria for craftsmanship, color and design- and then assign a wage scale accordingly. We threw rugs on the floor until rugs covered the entire room. On our hands and knees we crawled across the floor examining each rug as a lively discussion ensued.

Colored sawdust used to create a Semana Santa street rug.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Over an eighteen month long period I travelled to Guatemala quarterly to conduct workshops. From one workshop to the next Reyna and I built on sequential skill sets. In between workshops, Reyna provided follow-up, ensuring the women comprehended and implemented the workshop’s object lessons. The women would travel to our small office, some traveling from homes located four hours and many bus transfers away, to deliver rugs and receive payment. At the office, they would be welcomed with a snack and then Reyna would offer feedback, sometimes requiring the artist to change her design on the spot to comply with the design criterion before getting paid.

Other times Cheryl and Reyna travelled these same long routes to visit the rug makers in their remote villages. The two checked on production progress and also followed up with the artists-as-design-teachers to determine how the transfer of information was proceeding. Cheryl gathered baseline empirical data (number of people living in the dwelling, how many children lived in the dwelling and more). They also noted if the home had electricity or if there was a table and chair for the artisan to work upon- or- did the artist work at rug making while propped upon the family bed? It was during these community visits that seeds for Multicolores’ social programs were planted. (Multicolores now offers social services to our artisan members. The services require a measure of co-payment from the artists; we do not believe in ‘hand outs.’ Services include a program to buy furniture and lighting for the artist’s workplace, a family-wide health insurance plan and more.)

One day Yolanda, an accomplished traje weaver with an entrepreneurial spirit, whose rugs were consistently among the first to sell in any collection, complained to Reyna about the wages paid. She believed her rugs were a higher value then others because her rugs were more detailed and she did not think it fair that she was paid the same price as everyone else. She was right. A class discussion ensued about critiquing each rug. It was important to agree upon criteria for craftsmanship, color and design- and then assign a wage scale accordingly. We threw rugs on the floor until rugs covered the entire room. On our hands and knees we crawled across the floor examining each rug as a lively discussion ensued.

Examining rugs to arrive at a consensus on quality and pricing.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Eventually Reyna asked the women, “Could they see a difference in quality- did some rugs have more detail then others?” “Yes,” they all replied, some rugs had much more detail then others. “Did some rugs adhere more closely to the design principles?” “Yes,” they did. “Were some rugs better crafted- for example, did some rugs lay more flat or have fewer threads on the surface?” “Yes,” they could see that too. “Well,” she asked, “do you think the rugs that are better crafted, that adhere to the design principles and have more detail should receive a higher price?” “Yes,” everyone agreed. Then she asked the women to carefully examine all the rugs one more time because we would now vote on rugs possessing the best examples in each of the three categories and their votes would define criterion henceforth -along with prices paid.

Reyna gave each woman bits of paper to vote their opinion on: 1) best craftsmanship (the rug laid flat and had little or no frayed threads resting on the rug’s surface); 2) the design was taken from traje; and 3) the rug was detailed and possessed energy and vitality. Votes were tallied and scores were announced. Some of the women lobbied for a higher score but eventually all rugs were graded and the women had arrived, more or less, at a consensus. Their decision resulted in a three-tiered pricing system and very quickly thereafter, almost overnight, or so it seemed, design and craftsmanship improved.

Like artists everywhere, the women’s designs continue to evolve. A 2018 Story Rug workshop built upon the women’s design skills with two new compositional techniques. Composition making techniques covered in this workshop, with ongoing follow up conducted by Maddy Kreider Carlson, Multicolores’ new Creative Director were: 1. Incongruous use of imagery. (Think of the Mexican painter Frieda Kahlo’s self portrait as a wounded deer. Incongruous use of imagery invites combining images which may not exist in real life to convey an emotional truth.) And 2. Hierarchical proportion (the use of exaggerated scale to signify importance and design focal point). As a result of this workshop, and Maddy’s on-going follow-up, the women accessed fertile new sources of design inspiration. Incorporating their new knowledge with their previous skills, the artists began to create rugs portraying cultural and community myths, family stories and more.

Informally, on occasion, I’ve asked several of the artists if the design skills learned in rug making have influenced or been applied to other areas of their textile production. While no means exhaustive, they each replied “yes.” Some of the artists create beadwork to supplement their income; others weave huipils and traditional garments. Each artist said they are now able to articulate their design decisions and approach these decisions more intentionally.

Multicolores provides on-going access to opportunities to their membership on two fronts: Social services and remedial artistic training. Of key importance, the organization buys all members’ production --provided the works adhere to established criteria. Knowing their work will be purchased by the organization allows the artists a measure of financial ease along with an ability to plan their lives.

In addition to accessing social services mentioned briefly earlier in this article, and participating in classes to expand their artistry, the women enumerate other benefits: they grow confident. They begin to view themselves as capable of success in the market place. As their self-esteem rises, family members begin to perceive them differently, too. Respect grows.

In Guatemala, women from small rural villages seldom have opportunities to travel to other regions of the country or indeed, their wider communities. They seldom grow friendships beyond their church or immediate community or language group. They seldom have an opportunity to meet or interact with foreigners. Yet through their association with Multicolores opportunities are made available; the artists gain confidence navigating transportation systems as they periodically commute to our workshops and office. Through their participation in workshops they come together with their fellow Multicolores artists from disparate regions and language groups. They come to know one another as Maya women who face similar challenges in different communities. They come to know one another as artists and makers of one-of-a-kind rugs. They grow mutual respect and draw inspiration from each other’s artistic accomplishments. Like women everywhere, who come together united in purpose, friendships are born. By participating in weeklong rug hooking tours, where North Americans travel to Guatemala to learn the craft from the Maya artists, they engage with foreigners through the common bond of rug hooking. They share photographs and stories about their respective families, they learn about the joys and sometimes the sorrows of one another’s lives as they explore rug hooking the Maya way. And finally, the women of Multicolores are offered opportunities to share their knowledge and mentor others.

To learn more about our work in Guatemala, read Rug Money: How A Group Of Maya Women Changed Their Lives Through Art And Innovation published by Thrums Books, 2018. Visit Multicolores at www.multicolores.org.

Examining rugs to arrive at a consensus on quality and pricing.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Eventually Reyna asked the women, “Could they see a difference in quality- did some rugs have more detail then others?” “Yes,” they all replied, some rugs had much more detail then others. “Did some rugs adhere more closely to the design principles?” “Yes,” they did. “Were some rugs better crafted- for example, did some rugs lay more flat or have fewer threads on the surface?” “Yes,” they could see that too. “Well,” she asked, “do you think the rugs that are better crafted, that adhere to the design principles and have more detail should receive a higher price?” “Yes,” everyone agreed. Then she asked the women to carefully examine all the rugs one more time because we would now vote on rugs possessing the best examples in each of the three categories and their votes would define criterion henceforth -along with prices paid.

Reyna gave each woman bits of paper to vote their opinion on: 1) best craftsmanship (the rug laid flat and had little or no frayed threads resting on the rug’s surface); 2) the design was taken from traje; and 3) the rug was detailed and possessed energy and vitality. Votes were tallied and scores were announced. Some of the women lobbied for a higher score but eventually all rugs were graded and the women had arrived, more or less, at a consensus. Their decision resulted in a three-tiered pricing system and very quickly thereafter, almost overnight, or so it seemed, design and craftsmanship improved.

Like artists everywhere, the women’s designs continue to evolve. A 2018 Story Rug workshop built upon the women’s design skills with two new compositional techniques. Composition making techniques covered in this workshop, with ongoing follow up conducted by Maddy Kreider Carlson, Multicolores’ new Creative Director were: 1. Incongruous use of imagery. (Think of the Mexican painter Frieda Kahlo’s self portrait as a wounded deer. Incongruous use of imagery invites combining images which may not exist in real life to convey an emotional truth.) And 2. Hierarchical proportion (the use of exaggerated scale to signify importance and design focal point). As a result of this workshop, and Maddy’s on-going follow-up, the women accessed fertile new sources of design inspiration. Incorporating their new knowledge with their previous skills, the artists began to create rugs portraying cultural and community myths, family stories and more.

Informally, on occasion, I’ve asked several of the artists if the design skills learned in rug making have influenced or been applied to other areas of their textile production. While no means exhaustive, they each replied “yes.” Some of the artists create beadwork to supplement their income; others weave huipils and traditional garments. Each artist said they are now able to articulate their design decisions and approach these decisions more intentionally.

Multicolores provides on-going access to opportunities to their membership on two fronts: Social services and remedial artistic training. Of key importance, the organization buys all members’ production --provided the works adhere to established criteria. Knowing their work will be purchased by the organization allows the artists a measure of financial ease along with an ability to plan their lives.

In addition to accessing social services mentioned briefly earlier in this article, and participating in classes to expand their artistry, the women enumerate other benefits: they grow confident. They begin to view themselves as capable of success in the market place. As their self-esteem rises, family members begin to perceive them differently, too. Respect grows.

In Guatemala, women from small rural villages seldom have opportunities to travel to other regions of the country or indeed, their wider communities. They seldom grow friendships beyond their church or immediate community or language group. They seldom have an opportunity to meet or interact with foreigners. Yet through their association with Multicolores opportunities are made available; the artists gain confidence navigating transportation systems as they periodically commute to our workshops and office. Through their participation in workshops they come together with their fellow Multicolores artists from disparate regions and language groups. They come to know one another as Maya women who face similar challenges in different communities. They come to know one another as artists and makers of one-of-a-kind rugs. They grow mutual respect and draw inspiration from each other’s artistic accomplishments. Like women everywhere, who come together united in purpose, friendships are born. By participating in weeklong rug hooking tours, where North Americans travel to Guatemala to learn the craft from the Maya artists, they engage with foreigners through the common bond of rug hooking. They share photographs and stories about their respective families, they learn about the joys and sometimes the sorrows of one another’s lives as they explore rug hooking the Maya way. And finally, the women of Multicolores are offered opportunities to share their knowledge and mentor others.

To learn more about our work in Guatemala, read Rug Money: How A Group Of Maya Women Changed Their Lives Through Art And Innovation published by Thrums Books, 2018. Visit Multicolores at www.multicolores.org.

Hooked rug, 5’x7’ rug by Irma Churunel depicting Nahuales or Maya glyphs; recycled clothing on cotton ground cloth.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Hooked rug, 5’x7’ rug by Irma Churunel depicting Nahuales or Maya glyphs; recycled clothing on cotton ground cloth.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Hooked rug, 4’x 6’ rug by Yolanda Calgual Morales depicting traje of Chichicastenango surrounded by nature. Made with recycled clothing on cotton ground cloth.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Hooked rug, 4’x 6’ rug by Yolanda Calgual Morales depicting traje of Chichicastenango surrounded by nature. Made with recycled clothing on cotton ground cloth.

Photo Credit: Mary Anne, Wise

Issue #006, Autumn, 2020 ISSN: 2581- 9410 INTRODUCTION No one had ever come up with the concept of teaching design to artisans until 2005, when Judy Frater launched Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya. Hence, teaching artisans design was new for anyone who taught in the formative years. Furthermore, for each course we were presented with a curriculum and we had to create a syllabus. Craft in the Indian context is passed on from one generation of artisans to the next. The making skills can be acquired in a conventional design school, but that would be incomplete knowledge. What about the cultural context? Hence, when teaching design to crafts people it came naturally for us to learn and draw from the local culture to make education meaningful. We customized classroom activities according to the group dynamics every year, emphasizing experiential learning. Both of us have taught various courses within the Design and Business and Management for Artisans (BMA) courses at Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya and Somaiya Kala Vidya. Here we reflect on our experiences of teaching traditional artisans. Shwetha In 2008, when I was approached to teach the course Concept, Communication, Projects for artisans, I was intrigued but extremely nervous. Travelling from Bangalore to the middle of a desert itself was quite an adventure. Two flights and a long drive later, I found myself in a beautiful campus oasis. It was truly unlike any “college” I had been to. I was nervous because I did not know the language and was concerned about whether the students would be able to follow my broken Hindi. As I was settling down, a vehicle came up the dusty road. The students started pouring out, 12 men, most of them 5-10 years older than I was. They were busy unloading their luggage, talking to one another and had not noticed me. Suddenly one student saw me and before he could stop himself said, “Arre yeh to bacchi hain!” (She is a child). Even as the other students tried to shush him, I found myself blurting out, “Haan chhoti hoon, lekin hum ek doosre se seekh sakte hain na? “(well yes I am younger than you, but maybe we can both learn from each other?) I told them frankly that coming from South India, I had only bookish knowledge about their crafts, so if they taught me about their craft, I could teach them about design. That set the tone for the rest of the class and has been the mindset with which I approach every class I have taught in SKV: a mutual need to learn and explore. The diversity of the crafts that we had to deal with in the men’s course (weaving, bandhani and Ajrakh) and the different age groups meant I had to think differently while planning the exercises. I had to start with familiarizing myself with the local culture, understanding each student's craft, customs and rituals. Conceptualizing and designing exercises that appealed to each craft and were adaptable was key. My first teaching assignment was quite an eye opener and I had to learn to let go of certain teaching methods that were deemed the “correct” way. For instance, in a conventional setting the students are required to work in the classroom /studio for a set number of hours, In SKV the students are allowed to go around campus and work on their assignments; they are not bound by the classroom and there is an understanding that faculty will be available for them at all times. I had to think of innovative, very often experimental ideas to get the point across. More importantly I learned to adapt and go with the flow.

Jivaben presenting a product developed for a selected consumer to LOkesh 2009.

credit : Judy Frater

LOkesh

I had conducted workshops for traditional artisans in which I had instructed them to make new motifs or products that I had designed. But my first experience of teaching design to artisans was when I was invited to Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya in 2007. Until then, I had never thought an artisan could design new ideas. The challenge I perceived was how to make a village artisan think of new designs for a wider audience. I was taken aback with the rich presentation the students made on the first day of class. I felt a pressing need to understand who these women were. Where did they come from? From the very first day, after class I started visiting the village to educate myself about their cultural background. Thereafter teaching became easier as I started using examples from what I saw in their village and homes to explain concepts of design. I formed a deep appreciation of their ethnic background; that was the starting point for my long teacher-student relationship. I felt I was learning from them as much as I was teaching.

CONNECTING WITH CULTURAL / GEOGRAPHIC CONTEXT

Shwetha

I agree that the most interesting and important factor has been to bring in the cultural context while teaching. Given that the students come from culturally rich backgrounds and craft is an integral part of their lives, I find it most effective to draw from experiences and examples to which the students can relate. This experience differs for each student, be it by craft, gender or geography.

Men’s and women’s classes are separate at SKV. When I teach both men's and the women's courses, the drastic differences in their experiences and exposures is clear. I make a conscious effort to provide different examples and parallels while teaching different groups. For instance, when providing the women an example of the design process in which all components come together to create a final design/product, I give them a cooking example, of how different ingredients put together make the final dish. For the men, I try and relate it to the dyeing process or the setting up of a loom, which involve different steps, all of which need to be completed in order to get a final product. Drawing from what students know and understand makes it easy to convey the point.

LOkesh

During the Concept, Communication, Projects course the students learn how to work on a theme, starting with a colour story. The theme becomes a direction for innovation within their textile tradition. A professional international colour forecast that is donated to Somaiya Kala Vidya is presented to the class. The presentation is in the format of visual boards creating stories such as Going Back to Nature, Constructivism in Art, Drowning in Splendor etc. Each story is accompanied by a set of 6 to 7 colours. Students are encouraged to select the colour story they like most considering their craft context.

Knowing the culture and language is an advantage for the teacher. However, the key is to creatively make connections between local culture and design concepts. When I present the colour forecast, I equate it to the local term varta, (story). We discuss how heritage and craft have a story. The characters in this story are motifs having meaning for maker and user; the raw materials relate to the region or a trade system; layouts and colours are specific to age groups, and so on.

Colour is usually the first element to which a consumer is attracted. With an international colour forecast, seeds for new design collections are sown. How relevant an international colour forecast is to India is less relevant here. Important is that it offers a good starting point for learning. The colour forecast has proven a successful tool without fail over the years. During my class the mantra for interpreting this tool is ‘think globally and act locally.’ While we refer to international forecasts, the interpretation takes place in the artisan’s world. What I offer is a look at their familiar world with a fresh perspective.

At each stage of the learning process, the students are offered options, rather than forcing one idea on them. This gives students ownership and encourages them to take independent, creative decisions. Eventually their field experience and explorations become the foundation for a new design concept which culminates in a collection.

OVERCOMING LIMITATIONS OF THE SITUATION: THE CAMPUS/ STUDENT BACKGROUND

Jivaben presenting a product developed for a selected consumer to LOkesh 2009.

credit : Judy Frater

LOkesh

I had conducted workshops for traditional artisans in which I had instructed them to make new motifs or products that I had designed. But my first experience of teaching design to artisans was when I was invited to Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya in 2007. Until then, I had never thought an artisan could design new ideas. The challenge I perceived was how to make a village artisan think of new designs for a wider audience. I was taken aback with the rich presentation the students made on the first day of class. I felt a pressing need to understand who these women were. Where did they come from? From the very first day, after class I started visiting the village to educate myself about their cultural background. Thereafter teaching became easier as I started using examples from what I saw in their village and homes to explain concepts of design. I formed a deep appreciation of their ethnic background; that was the starting point for my long teacher-student relationship. I felt I was learning from them as much as I was teaching.

CONNECTING WITH CULTURAL / GEOGRAPHIC CONTEXT

Shwetha

I agree that the most interesting and important factor has been to bring in the cultural context while teaching. Given that the students come from culturally rich backgrounds and craft is an integral part of their lives, I find it most effective to draw from experiences and examples to which the students can relate. This experience differs for each student, be it by craft, gender or geography.

Men’s and women’s classes are separate at SKV. When I teach both men's and the women's courses, the drastic differences in their experiences and exposures is clear. I make a conscious effort to provide different examples and parallels while teaching different groups. For instance, when providing the women an example of the design process in which all components come together to create a final design/product, I give them a cooking example, of how different ingredients put together make the final dish. For the men, I try and relate it to the dyeing process or the setting up of a loom, which involve different steps, all of which need to be completed in order to get a final product. Drawing from what students know and understand makes it easy to convey the point.

LOkesh

During the Concept, Communication, Projects course the students learn how to work on a theme, starting with a colour story. The theme becomes a direction for innovation within their textile tradition. A professional international colour forecast that is donated to Somaiya Kala Vidya is presented to the class. The presentation is in the format of visual boards creating stories such as Going Back to Nature, Constructivism in Art, Drowning in Splendor etc. Each story is accompanied by a set of 6 to 7 colours. Students are encouraged to select the colour story they like most considering their craft context.

Knowing the culture and language is an advantage for the teacher. However, the key is to creatively make connections between local culture and design concepts. When I present the colour forecast, I equate it to the local term varta, (story). We discuss how heritage and craft have a story. The characters in this story are motifs having meaning for maker and user; the raw materials relate to the region or a trade system; layouts and colours are specific to age groups, and so on.

Colour is usually the first element to which a consumer is attracted. With an international colour forecast, seeds for new design collections are sown. How relevant an international colour forecast is to India is less relevant here. Important is that it offers a good starting point for learning. The colour forecast has proven a successful tool without fail over the years. During my class the mantra for interpreting this tool is ‘think globally and act locally.’ While we refer to international forecasts, the interpretation takes place in the artisan’s world. What I offer is a look at their familiar world with a fresh perspective.

At each stage of the learning process, the students are offered options, rather than forcing one idea on them. This gives students ownership and encourages them to take independent, creative decisions. Eventually their field experience and explorations become the foundation for a new design concept which culminates in a collection.

OVERCOMING LIMITATIONS OF THE SITUATION: THE CAMPUS/ STUDENT BACKGROUND

Discussing with Lakhuben Rabari her presentation and display 2013.

credit : Judy Frater

Shwetha

The simple, small town campus of SKV, and the students’ limited experience present challenges. The Merchandising and Presentation course completes the students’ design education. In this final course students view and review their entire year's work. They learn how to effectively present themselves, display their products, and create brand identities and communication collaterals. The design course culminates in a jury made up of professionals from the textile and craft industry, wherein the students' work and final collections are displayed and critiqued. Lack of confidence and the language barrier make the students hesitate while presenting. The way I approach it is to start from understanding each student's journey. Identifying each student’s” Aha” moment is the first step. Once students manage to identify that moment, it becomes easier for them to view their journey and build a presentation from there.

Students learn different display techniques. The core focus is on using available materials and innovating to showcase their craft and culture effectively through their display. Getting students to explore their surroundings and find or make props using materials around them makes them think creatively and helps overcome the resource limitations. Suddenly an earthen pot lying in the corner becomes a display prop for a stole, branches are tied together and made into a stand for products. I have found that some of the most authentic and evocative displays come out of the material and spaces around us.

LOkesh

In the Market Orientation course, students learn costing. During one costing exercise, I encountered a woman artisan who could barely write anything except her name and numbers. She knew how to count, but she could not write the calculations. I encouraged her to write calculations and draw her product so she remembered what the context was. I was surprised to see her spend time after class hours learning how to write multiplications. The class was a mix of older and younger students. The younger girls were fast with calculation would explain to the older woman and soon she could also manage. In turn, the younger girls learned from the experience of the older craftswoman. Thus a mix of age in the same class, a unique feature not practiced in mainstream design institutes in India, becomes an advantage.

To address the limitation of non-literacy, I made a template with symbols. I used symbols of thread/ yarn/ cloth for depicting raw materials, a symbol of a fan for overheads, a van denoting transportation cost, a sales tag for selling price, a bag of cash for profit and so on. The template had a place for drawing the product or placing a photo of the product with a code number. All the information depicted through symbols is also mentioned in Gujarati text. Therefore, in the future, whenever confused the artisan could re-confirm the information through a family member or friend who could read.

We also taught costing new designs through cooking! The artisans were assigned to cost their textiles. Following this they cooked a meal, starting from purchasing the materials to preparing the food, serving and costing it. Usually artisans forget to account for the cooking gas and the value of their own time. The breakup of visible and non-visible elements of cooking is applied to learning to cost textile products.

PRACTICAL and EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

Discussing with Lakhuben Rabari her presentation and display 2013.

credit : Judy Frater

Shwetha

The simple, small town campus of SKV, and the students’ limited experience present challenges. The Merchandising and Presentation course completes the students’ design education. In this final course students view and review their entire year's work. They learn how to effectively present themselves, display their products, and create brand identities and communication collaterals. The design course culminates in a jury made up of professionals from the textile and craft industry, wherein the students' work and final collections are displayed and critiqued. Lack of confidence and the language barrier make the students hesitate while presenting. The way I approach it is to start from understanding each student's journey. Identifying each student’s” Aha” moment is the first step. Once students manage to identify that moment, it becomes easier for them to view their journey and build a presentation from there.

Students learn different display techniques. The core focus is on using available materials and innovating to showcase their craft and culture effectively through their display. Getting students to explore their surroundings and find or make props using materials around them makes them think creatively and helps overcome the resource limitations. Suddenly an earthen pot lying in the corner becomes a display prop for a stole, branches are tied together and made into a stand for products. I have found that some of the most authentic and evocative displays come out of the material and spaces around us.

LOkesh

In the Market Orientation course, students learn costing. During one costing exercise, I encountered a woman artisan who could barely write anything except her name and numbers. She knew how to count, but she could not write the calculations. I encouraged her to write calculations and draw her product so she remembered what the context was. I was surprised to see her spend time after class hours learning how to write multiplications. The class was a mix of older and younger students. The younger girls were fast with calculation would explain to the older woman and soon she could also manage. In turn, the younger girls learned from the experience of the older craftswoman. Thus a mix of age in the same class, a unique feature not practiced in mainstream design institutes in India, becomes an advantage.

To address the limitation of non-literacy, I made a template with symbols. I used symbols of thread/ yarn/ cloth for depicting raw materials, a symbol of a fan for overheads, a van denoting transportation cost, a sales tag for selling price, a bag of cash for profit and so on. The template had a place for drawing the product or placing a photo of the product with a code number. All the information depicted through symbols is also mentioned in Gujarati text. Therefore, in the future, whenever confused the artisan could re-confirm the information through a family member or friend who could read.

We also taught costing new designs through cooking! The artisans were assigned to cost their textiles. Following this they cooked a meal, starting from purchasing the materials to preparing the food, serving and costing it. Usually artisans forget to account for the cooking gas and the value of their own time. The breakup of visible and non-visible elements of cooking is applied to learning to cost textile products.

PRACTICAL and EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

Reaching a consensus on the exhibition name and teams - BMA 2014

credit: Judy Frater

Reaching a consensus on the exhibition name and teams - BMA 2014

credit: Judy Frater

Discussing Brand USP by researching existing brands, BMA 2014.

Credit : Judy Frater

Shwetha

A key factor I keep in mind while designing exercises is to make them practical and fun. I feel students understand concepts better when an activity makes them think creatively and get involved.

The culmination of the Business and Management for Artisans course (BMA) is an exhibition planned by the students, from choosing the venue, logistics, display, PR etc.

They are split into groups and each group takes on responsibilities like logistics, stock taking, expenses...etc. Doing this exercise, not only are students involved in every aspect, they also understand the amount of work that goes into setting up an exhibition and value it more. They learn to take responsibility for their decisions.

Students often need financial aid for the exhibition, usually for advertisements and PR. I give them the task of creating a pitch and negotiating with SKV for a Win-Win situation. This is always an eye opener: they never thought they could ask!

Discussing Brand USP by researching existing brands, BMA 2014.

Credit : Judy Frater

Shwetha

A key factor I keep in mind while designing exercises is to make them practical and fun. I feel students understand concepts better when an activity makes them think creatively and get involved.

The culmination of the Business and Management for Artisans course (BMA) is an exhibition planned by the students, from choosing the venue, logistics, display, PR etc.

They are split into groups and each group takes on responsibilities like logistics, stock taking, expenses...etc. Doing this exercise, not only are students involved in every aspect, they also understand the amount of work that goes into setting up an exhibition and value it more. They learn to take responsibility for their decisions.

Students often need financial aid for the exhibition, usually for advertisements and PR. I give them the task of creating a pitch and negotiating with SKV for a Win-Win situation. This is always an eye opener: they never thought they could ask!

Juned Khatri studying ship-making for his theme 2016.

credit : LOkesh Ghai

Juned Khatri studying ship-making for his theme 2016.

credit : LOkesh Ghai

Somaiya Kala Vidya class of 2019 field trip to Khari Nadi.

credit : LOkesh Ghai

LOkesh

In Concept, Communication, Projects, the students learn how to draw inspiration from local culture or nature. Instead of borrowing reference images form a magazine or downloading from the internet, they experience their inspirations.

The forecast theme of Constructivism in Art was localized and experienced by visiting local potters in Gundiyali village, followed by studying the art of ship-making by hand at Mandvi port. For the theme of Going Back to Nature, the class visited a wild life sanctuary followed by a visit to an ancient river bed. During these site visits the students drew, painted, took photographs, recorded sounds and collected natural elements such as leaves and pebbles. Thus they experienced the inspiration, and through the process generated visual imagery for reference, making the project original and personal.

PEER LEARNING AND INDIVIDUAL ATTENTION DURING CLASSES

Somaiya Kala Vidya class of 2019 field trip to Khari Nadi.

credit : LOkesh Ghai

LOkesh

In Concept, Communication, Projects, the students learn how to draw inspiration from local culture or nature. Instead of borrowing reference images form a magazine or downloading from the internet, they experience their inspirations.

The forecast theme of Constructivism in Art was localized and experienced by visiting local potters in Gundiyali village, followed by studying the art of ship-making by hand at Mandvi port. For the theme of Going Back to Nature, the class visited a wild life sanctuary followed by a visit to an ancient river bed. During these site visits the students drew, painted, took photographs, recorded sounds and collected natural elements such as leaves and pebbles. Thus they experienced the inspiration, and through the process generated visual imagery for reference, making the project original and personal.

PEER LEARNING AND INDIVIDUAL ATTENTION DURING CLASSES

Tosif Khatri explaining his Logo concept to the jury members 2019

Credit : Judy Frater

Shwetha

Peer learning and providing individual attention are key concepts in SKV. We encourage alumni to participate as jury members and share their feedback with the students after each course. In the last course, Merchandising and Presentation, students’ families are invited for the presentation of the entire year's work and they are encouraged to participate in the Q & A sessions. The feedback and recognition from families, who are often artisans themselves, means a lot to the students.

To critically analyze one's own work and showcase the best pieces becomes important; in a limited space like an exhibition, what one chooses to display can make him stand out from the crowd. Faced with the dilemma of trying to fit an entire year's work into two panels, students are often unable to choose their best work or to recognize their strengths. An exercise that works is to encourage students to ask classmates to give them critical feedback and choose the pieces they like best. Often students are surprised with the selections, as they would not have viewed their own work in the same way.

Similarly, designing a logo is a very personal endeavor, and students often get stuck or too attached to convey a particular idea or concept. An effective exercise is asking students to exchange their logo ideas with each other for a few hours. This works on two levels: students have to explain their concepts to their peers, which helps them articulate their thoughts. Second, students get a fresh perspective, and a different direction from which to work. It encourages them to learn from their peers and value each other’s feedback.

Tosif Khatri explaining his Logo concept to the jury members 2019

Credit : Judy Frater

Shwetha

Peer learning and providing individual attention are key concepts in SKV. We encourage alumni to participate as jury members and share their feedback with the students after each course. In the last course, Merchandising and Presentation, students’ families are invited for the presentation of the entire year's work and they are encouraged to participate in the Q & A sessions. The feedback and recognition from families, who are often artisans themselves, means a lot to the students.

To critically analyze one's own work and showcase the best pieces becomes important; in a limited space like an exhibition, what one chooses to display can make him stand out from the crowd. Faced with the dilemma of trying to fit an entire year's work into two panels, students are often unable to choose their best work or to recognize their strengths. An exercise that works is to encourage students to ask classmates to give them critical feedback and choose the pieces they like best. Often students are surprised with the selections, as they would not have viewed their own work in the same way.

Similarly, designing a logo is a very personal endeavor, and students often get stuck or too attached to convey a particular idea or concept. An effective exercise is asking students to exchange their logo ideas with each other for a few hours. This works on two levels: students have to explain their concepts to their peers, which helps them articulate their thoughts. Second, students get a fresh perspective, and a different direction from which to work. It encourages them to learn from their peers and value each other’s feedback.

LOkesh teaching Ramesh Mesaniya 2019.

Credit : Judy Frater

LOkesh teaching Ramesh Mesaniya 2019.

Credit : Judy Frater

Beginning the Concept, Communication, Projects course with LOkesh Ghai

Credit : Judy Frater

LOkesh

At SKV the classroom has an environment that is both disciplined and friendly. A lot of class is about constructive dialogue, sometimes individually, sometimes in group discussions with peer learning. Students are encouraged to voice any challenge they face. During the Concept, Communication, Projects course, Poonambhai, a weaver, chose ‘air’ as his concept. I assigned him to depict air in his design. He protested that air cannot be depicted in weaving as it has no form. I asked him how one could feel air in weaving? After some discussion, he concluded that a missing yarn would be one way of showing air in weaving.

While sketching theme ideas on paper, Poonambhai was frustrated by the restriction of his colour palette. Again, he learned to design with restriction. Through individual encouragement and attention, he learned to move out of his comfort zone. He expanded his markets and started using new colour combinations. Over the years after graduation he has enjoyed exploring new colour stories.

GAMES AND ROLE PLAY

Shwetha

Teaching presentation skills and body language in the Merchandising and Presentation course becomes a bit difficult without offending anyone’s sensibilities. I have found role play exercises effective. This way, students experience and realize rather than being told what to do.

To introduce the importance of display and presentation, I usually kick off the course with a role play exercise of students acting as shopkeepers. Each shopkeeper is given a list of their store's characteristics. For example, one store would have a good display of products and good knowledge but rude behavior/disinterest toward customers, etc. The rest of the class acts as customers and visits each “Shop.” At the end of this exercise we discuss how they felt. This often leads to a healthy discussion on behavior, knowledge, display...etc.

In the Post Graduate BMA course, when I taught Sales and Marketing, one of the most fun exercises we did was split the students into groups and ask them to put up two food stalls; they were given a budget and a brief. One group had everything ready, but were so caught up that they forgot to inform us of their opening time. Another group had ice cream and though they scored on having a higher margin product, it was a really hot day and they struggled to serve us. Through this exercise we managed to touch on aspects like customer research, budgeting, promotion, etc.

IMPROMPTU EXERCISES

While teaching artisans, one thing is clear: as faculty we need to be flexible in our plans and adapt. Sometimes the exercise planned might not catch the attention of the students or it might feel a bit too complicated. At those times we usually have to think on our feet and come up with immediate ideas and solutions to get the point across in an interesting way.

LOkesh

During the Analyzing and Maximizing Business Performance course of the BMA, students make a detailed analysis of their sales at their exhibition. On the first day of the women’s session, everyone was too afraid to make a mistake dealing with actual sales figures. This prompted me to make up a game that would break the ice with numeracy. I told a student to throw a die, multiply the number by one hundred and that equals your sales. If you got number six, it was considered as sales cancelled and the amount was reduced from the current sales figure. The student passed the die to the next player and whoever made a thousand sales first was the winner. The game brought back enthusiasm for numbers and we went back to the invoice bills for accounting.

Shwetha

The first time I taught brand identity, the students had to translate concepts and ideas such as quality, good, and tradition into visual forms. I was struggling to explain how to simplify a concept in a drawing. After dinner the students were bored and wanted to play a game. I realised we could play Pictionary. Suddenly it went from a fun game to a teaching moment, where the students were trying to show concepts in simple line drawings. It has now become a favorite, a game in which students learn to depict and convey feelings, objects, and intentions visually.

CONCLUSION

As teachers our belief that artisans can learn design and implement this learning has only grown over the years. The artisan communities have experienced the benefit of education, thus encouraging the next generation of artisans to enroll and continue with their tradition of craft. We have been surprised by both men and women artisans' ability to find design solutions and rise to the challenge.

Over the years we have changed teaching methodology and the way we approach subjects to adapt to the ever changing market and technological advances. As faculty, we continue to learn about emerging trends and technology so we can adapt and evolve the syllabus for the students.

Teaching artisans at SKV, experiential learning, connecting to local culture, and engaging in dialogue result in a successful class. The role of the faculty is not to impose his or her aesthetics but to nurture how the students visualize an idea.

In the Post Covid situation, the way consumers think and shop will change drastically. Most exhibitions that artisans would have attended are going online and becoming virtual exhibitions. With removing the sense of touch and feel that is so inherent to craft products, it becomes even more critical that products are presented well, communication is clear and the story telling is apparent. For the future we as teachers will also need to adapt and change the way we teach and what we teach accordingly.

Beginning the Concept, Communication, Projects course with LOkesh Ghai

Credit : Judy Frater

LOkesh

At SKV the classroom has an environment that is both disciplined and friendly. A lot of class is about constructive dialogue, sometimes individually, sometimes in group discussions with peer learning. Students are encouraged to voice any challenge they face. During the Concept, Communication, Projects course, Poonambhai, a weaver, chose ‘air’ as his concept. I assigned him to depict air in his design. He protested that air cannot be depicted in weaving as it has no form. I asked him how one could feel air in weaving? After some discussion, he concluded that a missing yarn would be one way of showing air in weaving.

While sketching theme ideas on paper, Poonambhai was frustrated by the restriction of his colour palette. Again, he learned to design with restriction. Through individual encouragement and attention, he learned to move out of his comfort zone. He expanded his markets and started using new colour combinations. Over the years after graduation he has enjoyed exploring new colour stories.

GAMES AND ROLE PLAY

Shwetha

Teaching presentation skills and body language in the Merchandising and Presentation course becomes a bit difficult without offending anyone’s sensibilities. I have found role play exercises effective. This way, students experience and realize rather than being told what to do.

To introduce the importance of display and presentation, I usually kick off the course with a role play exercise of students acting as shopkeepers. Each shopkeeper is given a list of their store's characteristics. For example, one store would have a good display of products and good knowledge but rude behavior/disinterest toward customers, etc. The rest of the class acts as customers and visits each “Shop.” At the end of this exercise we discuss how they felt. This often leads to a healthy discussion on behavior, knowledge, display...etc.

In the Post Graduate BMA course, when I taught Sales and Marketing, one of the most fun exercises we did was split the students into groups and ask them to put up two food stalls; they were given a budget and a brief. One group had everything ready, but were so caught up that they forgot to inform us of their opening time. Another group had ice cream and though they scored on having a higher margin product, it was a really hot day and they struggled to serve us. Through this exercise we managed to touch on aspects like customer research, budgeting, promotion, etc.

IMPROMPTU EXERCISES

While teaching artisans, one thing is clear: as faculty we need to be flexible in our plans and adapt. Sometimes the exercise planned might not catch the attention of the students or it might feel a bit too complicated. At those times we usually have to think on our feet and come up with immediate ideas and solutions to get the point across in an interesting way.

LOkesh

During the Analyzing and Maximizing Business Performance course of the BMA, students make a detailed analysis of their sales at their exhibition. On the first day of the women’s session, everyone was too afraid to make a mistake dealing with actual sales figures. This prompted me to make up a game that would break the ice with numeracy. I told a student to throw a die, multiply the number by one hundred and that equals your sales. If you got number six, it was considered as sales cancelled and the amount was reduced from the current sales figure. The student passed the die to the next player and whoever made a thousand sales first was the winner. The game brought back enthusiasm for numbers and we went back to the invoice bills for accounting.

Shwetha

The first time I taught brand identity, the students had to translate concepts and ideas such as quality, good, and tradition into visual forms. I was struggling to explain how to simplify a concept in a drawing. After dinner the students were bored and wanted to play a game. I realised we could play Pictionary. Suddenly it went from a fun game to a teaching moment, where the students were trying to show concepts in simple line drawings. It has now become a favorite, a game in which students learn to depict and convey feelings, objects, and intentions visually.

CONCLUSION

As teachers our belief that artisans can learn design and implement this learning has only grown over the years. The artisan communities have experienced the benefit of education, thus encouraging the next generation of artisans to enroll and continue with their tradition of craft. We have been surprised by both men and women artisans' ability to find design solutions and rise to the challenge.

Over the years we have changed teaching methodology and the way we approach subjects to adapt to the ever changing market and technological advances. As faculty, we continue to learn about emerging trends and technology so we can adapt and evolve the syllabus for the students.

Teaching artisans at SKV, experiential learning, connecting to local culture, and engaging in dialogue result in a successful class. The role of the faculty is not to impose his or her aesthetics but to nurture how the students visualize an idea.

In the Post Covid situation, the way consumers think and shop will change drastically. Most exhibitions that artisans would have attended are going online and becoming virtual exhibitions. With removing the sense of touch and feel that is so inherent to craft products, it becomes even more critical that products are presented well, communication is clear and the story telling is apparent. For the future we as teachers will also need to adapt and change the way we teach and what we teach accordingly.