JOURNAL ARCHIVE

Issue #008, 2021 ISSN: 2581- 9410 I will share my thoughts on the relevance of Gandhian Science in the Indian Cotton Textile Industry and I would like us to consider why it was that Gandhi chose the spinning of cotton yarn as the vehicle of swaraj Could anyone meeting Gandhi in say 1893 in South Africa, when he was a London trained barrister dressed in Western dress, representing a prosperous merchant in a civil court case, could such a person ever have thought that Gandhi would one day not only change his attire to become what the Prime Minister of Britain Winston Churchill sarcastically called a ‘half-naked fakir’ but be able to put his finger on the crucial issue of village India’s poverty? How did this middle-class urban person from a prosperous Kathiawadi family take up the cause of a simple wooden gadget on which cotton yarn was spun? Which, by the way he only saw for the first time in Bijapur village in Gujarat in 1917, when he was already 48 years old? But with his sharp insight into Indian village life Gandhi was quick to figure out that cotton yarn spinning as part of the making of cotton cloth was the key to the self-sufficiency of the Indian village, since it employed literally millions of people and was one in which no other country could match India’s strength. This is what he writes in his weekly paper Harijan in 1940: ‘The spinning wheel represents to me’ he writes ‘the hope of the masses. The masses lost their freedom, such as it was, with the loss of the Charkha. The Charkha supplemented the agriculture of the villagers and gave it dignity. It was the friend and the solace of the widow. It kept the villagers from idleness. For, the Charkha included all the anterior and posterior industries - ginning, carding, warping, sizing, dyeing and weaving. These in their turn kept the village carpenter and the blacksmith busy. The Charkha enabled the seven hundred thousand villages to become self contained’ Cotton cloth has been made in India for around 5 thousand years. Since at least the time of the Roman Empire there had been a demand for Indian cotton fabrics in Europe, and they had been exported from India in great quantities from then until the nineteenth century. But it was a one-way trade, since there was nothing the West produced that Indians wanted in return, so India had to be paid in gold and silver, creating balance of payments problems for even the mighty Roman Empire: Pliny, the Roman historian of the 1st century AD calculates the value of the cotton textile trade between India and Rome at a hundred million sesterces [equal then to 15 million rupees] every year, and he complains that India is draining Rome of her gold. The gold and silver which poured into India went into the hands of the millions of farmers who grew the cotton, the millions of women who spun the yarn, and the millions of weavers who wove the cloth. It was certainly the largest manufactured trade item in the world in pre-industrial times. Indian cotton cloth, paid for in gold and silver, was arguably the source of India's fabled wealth. Not just the quantity, people marveled at the quality and variety of Indian cotton fabrics. Suleiman, an Arab trader who visited Calicut in 851 AD writes in his diary “..garments are made in so extraordinary a manner that nowhere else are the like to be seen. These garments are wove to that degree of fineness that they may be drawn through a ring of middling size”. Tome Pires, a Portugese traveler of the 16th century writes in 1515 from Malacca describing the ships that came there from Gujarat and the Coromandel coast, “…worth eighty to ninety thousand cruzados”, he says, “carrying cloth of thirty different sorts..” a hundred years later Pyrard de Laval, a French mariner says that Indian fabrics clothed “ everyone from the Cape of Good Hope to China, man and woman, …from head to foot.” It was not just fine cloth that India exported. Excavations in Egypt of pieces of cloth dating from the 5th to the 14th century AD have brought to light the ordinary cloth that India made for ordinary people, which was also exported, samples of which can be seen today in the Newberry collection housed at the Ashmolean museum in Oxford. The many different regions of the Indian sub-continent, with their specific soils and their specific micro-climates, nurtured different varieties of cotton plants, each one specifically adapted to its particular conditions. Farmers used the best of their own seeds for the next year’s planting, so that over the centuries each variety of cotton plant was constantly refined and improved while retaining its distinctive character Then the cotton seeds were separated by hand from the lint on small household gins in the farmer’s house and the best ones were stored for the next year’s planting. Cotton lint was spun into yarn on household charkhas, producing the variety of yarns that gave Indian fabrics their fabled diversity. There was a charkha in every household, rich and poor. For the poorer folk, spinning was livelihood, for the richer ones it was a leisure pastime. Dhunkars/carders walked the streets twanging their carding bows, waiting to be called in by household spinners to make their ginned cotton lint into slivers. This idyllic picture was disrupted by the Industrial Revolution in England. It’s a well known story: the first machines of the industrial revolution were spinning machines. They ushered in the age of mass production: in the late 18th century the first spinning mill was set up in England, followed by many others. The mills needed large quantities of cotton as raw material and so Indian cotton became a commodity for export rather than raw material for small-scale local weaving. Household ginning was no longer adequate to gin the large quantities in a short time that export production required, so large ginning machines were introduced into cotton growing areas. In these large ginning machines the seeds of the different varieties of cotton which had been so carefully kept separate for centuries were all mixed together and desi varieties carefully cultivated over the ages became mongrelized, dealing a mortal blow to the legendary diversity of Indian cottons. The English spinning mills began turning out huge quantities of yarn. And who was to buy these huge quantities of mill spun yarn? the weavers of India of course! Mill-spun cotton yarn began to be exported from England to India, destroying the livelihoods of millions of Indian spinners. Here is an extract from a letter written in 1828 and printed in the newspaper Samachar, by one such unfortunate person. This is what she says: When my age was five and a half gandas (a ganda is 4 years so she would have been 22) I became a widow with three daughters. My husband left nothing at the time of his death wherewith to maintain my old father-and-mother-in-law and three daughters.... At last as we were on the verge of starvation God showed me a way by which we could save ourselves. I began to spin on takli and charkha. In the morning I used to do the usual work of cleaning the household and then sit at the charkha till noon, and after cooking and feeding the old parents and daughters I would have my fill and sit spinning fine yarn on the takli. Thus I used to spin about a tola. The weavers used to visit our houses and buy the charkha yarn at three tolas per rupee. Whatever amount I wanted as advance from the weavers, I could get for the asking. This saved us from cares about food and cloth. In a few years' time I got together seven ganda rupees. With this I married one daughter. And in the same way all three daughters. There was no departure from the caste customs. Nobody looked down upon these daughters because I gave all concerned, what was due to them. When my father-in-law died I spent eleven ganda rupees on his shraddha. This money was lent me by the weavers which I repaid in a year and a half. ...And all this through the grace of the charkha. Now for 3 years we two women, mother-in-law and I, are in want of food. The weavers do not call at the house for buying yarn. Not only this, if the yarn is sent to the market, it is not sold even at one-fourth the old prices. I do not know how it happened. I asked many about it. They say that bilati yarn is being largely imported. The weavers buy that yarn and weave. I had a sense of pride that bilati yarn could not be equal to my yarn, but when I got bilati yarn I saw that it was better than my yarn. I heard that its price is Rs. 3 or Rs 4. per seer. (she sees that even though the yarn is smoother it is also cheaper) I beat my brow (she continues) and said, 'Oh God, there are sisters more distressed even than I. I had thought that all men of Bilat were rich, but now I see that there are women there who are poorer than I’ I fully realized the poverty which induced those poor women to spin. They have sent the product of so much toil out here because they could not sell it there. It would have been something if they were sold here at good prices. But it has brought our ruin only. Men cannot use the cloth out of this yarn even for two months; it rots away. I therefore entreat the spinners over there that, if they will consider this representation, they will be able to judge whether it is fair to send yarn here or not. This letter is reprinted by Gandhi in his paper Young India in 1931. It is the arrogance of imperialism that allows manufacture of yarn in England from cotton grown by slaves a thousand miles away, in America, to be sold in markets more thousands of miles away, in India, undercutting local manufacture. And it is Gandhi’s perfectly tuned intuition that grasps this and makes the charkha the symbol of the antithesis of imperialism: Swaraj. An opportunity for change comes when India throws off the colonial yoke and becomes independent. Independence from colonial rule provides a chance for the country to get rid of the colonial spinning technology it is burdened with. If Gandhi’s ideas on yarn spinning had been considered at this seminal moment, perhaps this could have come about… but this was not to be; his ideas were rejected outright by fellow patriots. Nehru and the scientist Meghnad Saha unfortunately did not engage with Gandhi’s ideas, but brushed them aside on the grounds as Saha said, that he advocated a return to ‘old world ideology’, to be discarded in favour of modern science and technology. Tagore repeatedly warned of the oversimplification he considered was inherent in Gandhi’s call for all to spin: “It is essential that the responsibility of swaraj should be accepted fully”, he said “and not as a matter of homespun yarn alone”. In fact Tagore famously dismissed the charkha as a distraction from “our task of all-round reconstruction”, while the All India Congress, with Nehru at its head, disowned it. As to Gandhi’s companions they unquestioningly accepted his ideas, but none of them took up a deep study into the relation between the cotton plant and the spinning process. Perhaps if Gandhi’s life had not been so tragically cut short soon after India’s independence he would have looked deeper into the question of yarn making. Perhaps he would have pointed Maganlal, his research-minded nephew, towards developing a spinning technology that could innovate machines that used the principle of hand-spinning to produce the vast quantities of yarn that the millions of hand weavers of the day needed. It could have been done with persistence and belief in the importance of yarn-spinning, but instead independent India chose to retain the spinning technology introduced by the EIC. Which meant that if our indigenous cottons the herbaceum and arboreum strains of the gossypium plant did not produce the long, strong cotton fibre this technology demanded then they must be abandoned in favour of foreign varieties, the American and Egyptian hirsutums and barbadenses. In other words, the demands of the machine began to dictate what nature should produce. A change of cotton varieties meant a change of the whole ecosystem in which they were grown: while the desis had been grown as rain-fed crops, the American varieties needed irrigation – a major change with 3 results – it added the huge costs of irrigation to the expenditure that the farmer had to incur, it depleted precious ground water and it increased humidity in the cotton fields. A humid climate is what encourages pests and in irrigated fields they increased by leaps and bounds, so that more technology was introduced to control them, laying the path for genetically modified cotton seeds in which the gene of an insect, Bacillus Thurigiensis is introduced into the cotton seed, producing the BT cotton which is in general use today. It is in this specific instance – the introduction of foreign varieties of cotton to suit an alien spinning technology - that I particularly miss the presence of Gandhian thought. Newly independent India should have framed science and technology policies for specific Indian circumstances and the strengths of the Indian samaaj. If technology development had been in the hands of Gandhi and his followers this is what they would have done - they would have come up with a spinning technology that could handle the different varieties of cotton that grew in the different regions of the country, as our hand-spinning and hand-weaving technologies were designed to do. The Gandhian way would have been to reject a spinning technology unsuited to desi cotton varieties, unsuited to handling diversity. Perhaps then we could have avoided the replacement of our indigenous cottons with the Americans, that have brought so much despair to Indian cotton farmers that lakhs of them have committed suicide..part of the farm suicides that P Sainath, chronicler of rural India calls ”the largest wave of suicides in history” I myself have been involved with cotton yarn spinning for many years and at this point I would like to share with you a brief insight into what we call the Malkha initiative, in which some steps have been taken towards making yarn on a small scale suited to the small scales of cotton growing and hand-weaving, what Gandhi refers to as “the anterior and posterior industries”. Malkha spinning units have a hundred times fewer spindles than commercial mills, (400 as compared to 40,000) and they produce a hundred times less yarn (40 kilos) per 8 hour shift, enough for 40 hand weavers. And here are a few slides to show you how the Malkha units work:

1.Malkha buys unbaled cotton lint rather than the lint that has been steam-pressed

1.Malkha buys unbaled cotton lint rather than the lint that has been steam-pressed

2. In the Malkha unit the lint is fed into a carder, which produces

2. In the Malkha unit the lint is fed into a carder, which produces

3. Carded sliver This carded sliver then goes through various stages

3. Carded sliver This carded sliver then goes through various stages

4. Before it becomes

4. Before it becomes

5. Yarn.

5. Yarn.

6. The yarn wound onto bobbins then reaches the loom

6. The yarn wound onto bobbins then reaches the loom

While Gandhi was supremely confident of India’s ability to take a path to the future based on its own civilizational values and suited to its own circumstances, the new rulers of independent India preferred instead to follow the direction of its erstwhile colonial masters. They felt that the science and technology developed in the West was the best for India. They thought that India’s historical mastery of cotton cloth making was irrelevant in the modern world, that in this modern world small-scale, decentralized hand-production must be replaced by mass production in large, centralized, energy-intensive mills and factories. Mass production, they thought, would increase India’s material wealth and the well being of the country would automatically follow.

They were wrong.

Seventy-five years after independence India lags behind in providing food, health and education to large numbers of the people of the country We see the deficiencies of our health systems particularly in these covid times. Inequality between rich and poor is at stratospheric levels, with the richest 10% holding 77% of the country’s wealth, while the poorest suffer from poverty similar to that of the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, as Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen point out. And of course the wealth of the country is increasing at the cost of the exploitation of natural resources by industrial production.... of course the profits made through that exploitation of natural resources are accumulated by those who control that industrial production, while the costs of the destruction are borne disproportionately by the poor. Cutting down forests to build highways, building big dams to generate energy has benefited big industry while destroying local environments and disabling the local industries that for ages have used the resources of the forests and rivers without causing them any harm. Look for example at how river waters had been used for centuries: Local dyers such as the kalamkari hand-painters of Kalahasti and the indigo dyers of Ilkal attributed the brightness of their colours to the flowing water of local rivers and streams: “The water of Hirehalla nala was what gave our indigo dyeing its sheen” says one of the dyers of Ilkal. These waters no longer flow, they’ve been dammed upstream to generate electricity for big industries. Indigo dyeing has been given up altogether in Ilkal, while the artists of Kalahasti have ironically to resort to the water being pumped into fields for irrigation to wash their paintings.

There are other ways in which the rights of villages were breached by colonial administrators, and which have not yet been restored by the rulers of independent India. Activities in the village which were the prerogative of local communities were snatched from their hands by colonial administrators. For example, fishing in local village ponds was a right allocated to local fishermen, but during colonial times were sold to the highest bidder. Bamboo from the forests from which local bamboo artisans made things of village use was now sold to be pulped for paper in the large paper mills set up in colonial days. Similar fates befell the collectors of minor forest produce, as well as to tappers of toddy trees and to sea-side salt makers.

As artisanal industries declined the village as a community made up of people providing their skills to an interdependent village economy, an economy firmly rooted in its specific place now turned the village instead into a collection of individuals with no professional relations amongst each other, and no reason to remain where they were. They became rootless, a supply of cannon-fodder for the new mass-production industries that sprang up in urban centres far from their village homes. These new industries were structured around the technology of machinery, creating as Jacques Ellul, the 20th century French philosopher says “an artificial world and hence radically different from the natural world”. No longer were tools made to serve humanity, now humanity had to service the needs of the machine.

This is the direction of technology development that India continues to follow today: in the view of the vast majority of the twentieth century Indian westernised elite the dominant position of Newtonian science is unquestioned. It seems as if that ‘science’ is synonymous with modernity and progress, and under its banner, it is possible to dub traditions as superstitions and to consign whole cultures to the dustbin of the unscientific. For example State policies devalue the knowledge of weaving communities, imposing alien technologies among skilled weaver communities that they have designated as primitive, such as the recent effort to introduce jacquard weaving on frame looms among the loin-loom weavers of North East India. If Gandhi’s views on the contrary had steered India’s technology development, it would be in the direction of flexibility rather than the uniformity necessary for mass production: we would have a plethora of flexible technologies that would adapt to the diversity of this vast subcontinent, as traditional Indian technologies, the charkha and the handloom are designed to do.

Flexible technology is what makes the spinning of multiple varieties of cotton possible, turning out different kinds of yarn in different regions that can be woven into a variety of cloths reflecting the heritage of each region. There’s no reason why modern technologies that enhance flexibility cannot be used for this purpose. Modern communication technologies such as social media can break the hold of the monopolistic market that demands large quantities of identical products; social media can broadcast information on small-scale local markets where the knowledge of the maker meets the expectation of the user directly, with just returns for the makers and made-to-order products for the buyers.

In the Indian situation diversity should be seen as an advantage, not a drawback. Diversity is the poetry of India’s cotton cloth; and it begins with the lint of the diverse cotton plants and needs spinning technologies suited to each. In our particular circumstances and considering our particular strengths we should encourage the development of a plethora of spinning technologies suited to spinning a diversity of yarns from a diversity of cotton varieties. We should do away with the dominance of industrial spinning machinery that demands from the farmer the one kind of cotton that it can process, and doles out to the weaver the one kind of yarn it can spin.

We should go in the opposite direction to that monoculture: growers, spinners and weavers of cotton in different regions should develop the particular technologies that suit them, which would make them confident in their own domains, participants in a network of equals. Technology development should be in the hands of the producers, anchored at the actual sites of production.

Today in the 21st century there are still millions of hand looms weaving cloth in India, distributed in the different parts of the country. A textile policy derived from the philosophy of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi would ensure that India would establish in this country a diverse, producer-owned, ecological industry in which local environments would be respected: the burden on nature would be limited by nature’s own boundaries. Subsistence for all rather than profit for a few would reign. This would be true swaraj, in tune with Gandhi’s maxim that “Earth provides enough to satisfy every man's need, but not every man's greed.”

Talk delivered at the Gandhi Science Lecture Series, Indian Academy of Sciences. 28 May,2021

[embed]https://youtu.be/oPq_OvVHwB0[/embed]

While Gandhi was supremely confident of India’s ability to take a path to the future based on its own civilizational values and suited to its own circumstances, the new rulers of independent India preferred instead to follow the direction of its erstwhile colonial masters. They felt that the science and technology developed in the West was the best for India. They thought that India’s historical mastery of cotton cloth making was irrelevant in the modern world, that in this modern world small-scale, decentralized hand-production must be replaced by mass production in large, centralized, energy-intensive mills and factories. Mass production, they thought, would increase India’s material wealth and the well being of the country would automatically follow.

They were wrong.

Seventy-five years after independence India lags behind in providing food, health and education to large numbers of the people of the country We see the deficiencies of our health systems particularly in these covid times. Inequality between rich and poor is at stratospheric levels, with the richest 10% holding 77% of the country’s wealth, while the poorest suffer from poverty similar to that of the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, as Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen point out. And of course the wealth of the country is increasing at the cost of the exploitation of natural resources by industrial production.... of course the profits made through that exploitation of natural resources are accumulated by those who control that industrial production, while the costs of the destruction are borne disproportionately by the poor. Cutting down forests to build highways, building big dams to generate energy has benefited big industry while destroying local environments and disabling the local industries that for ages have used the resources of the forests and rivers without causing them any harm. Look for example at how river waters had been used for centuries: Local dyers such as the kalamkari hand-painters of Kalahasti and the indigo dyers of Ilkal attributed the brightness of their colours to the flowing water of local rivers and streams: “The water of Hirehalla nala was what gave our indigo dyeing its sheen” says one of the dyers of Ilkal. These waters no longer flow, they’ve been dammed upstream to generate electricity for big industries. Indigo dyeing has been given up altogether in Ilkal, while the artists of Kalahasti have ironically to resort to the water being pumped into fields for irrigation to wash their paintings.

There are other ways in which the rights of villages were breached by colonial administrators, and which have not yet been restored by the rulers of independent India. Activities in the village which were the prerogative of local communities were snatched from their hands by colonial administrators. For example, fishing in local village ponds was a right allocated to local fishermen, but during colonial times were sold to the highest bidder. Bamboo from the forests from which local bamboo artisans made things of village use was now sold to be pulped for paper in the large paper mills set up in colonial days. Similar fates befell the collectors of minor forest produce, as well as to tappers of toddy trees and to sea-side salt makers.

As artisanal industries declined the village as a community made up of people providing their skills to an interdependent village economy, an economy firmly rooted in its specific place now turned the village instead into a collection of individuals with no professional relations amongst each other, and no reason to remain where they were. They became rootless, a supply of cannon-fodder for the new mass-production industries that sprang up in urban centres far from their village homes. These new industries were structured around the technology of machinery, creating as Jacques Ellul, the 20th century French philosopher says “an artificial world and hence radically different from the natural world”. No longer were tools made to serve humanity, now humanity had to service the needs of the machine.

This is the direction of technology development that India continues to follow today: in the view of the vast majority of the twentieth century Indian westernised elite the dominant position of Newtonian science is unquestioned. It seems as if that ‘science’ is synonymous with modernity and progress, and under its banner, it is possible to dub traditions as superstitions and to consign whole cultures to the dustbin of the unscientific. For example State policies devalue the knowledge of weaving communities, imposing alien technologies among skilled weaver communities that they have designated as primitive, such as the recent effort to introduce jacquard weaving on frame looms among the loin-loom weavers of North East India. If Gandhi’s views on the contrary had steered India’s technology development, it would be in the direction of flexibility rather than the uniformity necessary for mass production: we would have a plethora of flexible technologies that would adapt to the diversity of this vast subcontinent, as traditional Indian technologies, the charkha and the handloom are designed to do.

Flexible technology is what makes the spinning of multiple varieties of cotton possible, turning out different kinds of yarn in different regions that can be woven into a variety of cloths reflecting the heritage of each region. There’s no reason why modern technologies that enhance flexibility cannot be used for this purpose. Modern communication technologies such as social media can break the hold of the monopolistic market that demands large quantities of identical products; social media can broadcast information on small-scale local markets where the knowledge of the maker meets the expectation of the user directly, with just returns for the makers and made-to-order products for the buyers.

In the Indian situation diversity should be seen as an advantage, not a drawback. Diversity is the poetry of India’s cotton cloth; and it begins with the lint of the diverse cotton plants and needs spinning technologies suited to each. In our particular circumstances and considering our particular strengths we should encourage the development of a plethora of spinning technologies suited to spinning a diversity of yarns from a diversity of cotton varieties. We should do away with the dominance of industrial spinning machinery that demands from the farmer the one kind of cotton that it can process, and doles out to the weaver the one kind of yarn it can spin.

We should go in the opposite direction to that monoculture: growers, spinners and weavers of cotton in different regions should develop the particular technologies that suit them, which would make them confident in their own domains, participants in a network of equals. Technology development should be in the hands of the producers, anchored at the actual sites of production.

Today in the 21st century there are still millions of hand looms weaving cloth in India, distributed in the different parts of the country. A textile policy derived from the philosophy of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi would ensure that India would establish in this country a diverse, producer-owned, ecological industry in which local environments would be respected: the burden on nature would be limited by nature’s own boundaries. Subsistence for all rather than profit for a few would reign. This would be true swaraj, in tune with Gandhi’s maxim that “Earth provides enough to satisfy every man's need, but not every man's greed.”

Talk delivered at the Gandhi Science Lecture Series, Indian Academy of Sciences. 28 May,2021

[embed]https://youtu.be/oPq_OvVHwB0[/embed]

Ganesa, the lord of ganas, is considered the god of good luck and auspicious happenings. He is known by various names like Vighneswar Siddhidata, Girijaputra etc. Ganesa is worshipped alike by devotees of all communities. The birth-story of Ganesa has been referrd with slight variations in many Puranas, as Padma Purana, Matsya Purana, Linga Purana, Brahmavaivarta Purana. ,Skanda Purana and Siva Purana. The last one deals with this theme in such an interesting manner that during the late medieval period it becomes very popular among the artists, who carved out or painted the episode based on this text. Two doors have formed the subject matter of this paper. The story of the birth of Ganesa mentioned in Siva Purana states that once Jaya and Vijaya, friends of Parvati advised her to have a guard of her own, as almost all the ganas belonged only to Siva but Parvati did not pay any attention to this idea Once Siva entered the apartment in spite of Nandi's check, who was guarding the door. At this moment Parvati felt the need of having her own guard. Accordingly, she modelled a male child out of her toilet paste and infused life in it. Afterwards Parvati posted him at the main gate with instruction not allowing anyone inside as she was going for bathe. Meanwhile Siva came and tried to enter into the apartment. The guard, at the gate, did not allow him, even after a hot discussion. Parvati enquired about the noise and knowing the situation, she sent her approval to the guard to resist forced entry of Siva into her apartment. War took place between both the parties in which Parvati's Ganas won the war. This made Siva furious, Narad's admiration for Parvati's Gana made him more violent and he chopped off the head of Parvati's Gana On hearing this, Parvati also became very furious. By the time, all gods assembled there and tried to mediate. At last Parvati agreed on this condition that her son should regain life, which was accepted by Siva. He sent his gana's in northern direction and asked them to bring head of the first person whom they meet first. Accordingly, the head of baby elephant was brought by Ganas and it was fixed by Siva and Ganesa gained life and received the blessings of the gods (who assembled there at that time) including Siva himself. Besides this, the story is mentioned in Padma Purana, Marysa Purana,Skanda Purana, Brahmavaivarta Purana and Linga Purana also. While the former three refer the core of the story same as Siva Purana, where Parvati models that child out of the paste the latter two (Brahniavaivarta and Linga Purana) present comparatively altogether a different story which is not relvant here to the depiction of the door. While Padma and Marysa Purana present lord Ganesa with the elephant head right from very beginning Skanda Purana mentions that after cutting the head of Parvati's Gana, Siva fought with Gajasura and brought his head and fixed it on the top of the child's body. It is only in the Siva Purana that the Ganas brought the head of elephant on the order of Siva as depicted on doors, therefore, it is relevant that it is based on Siva Purana only," as scenes are painted like it. Presently two doors painted with the theme of Ganesa's birth, are housed in the National Museum, New Delhi. These belong to Orissa and are painted in folk styles and probably of 19th century. One of these has 24 medallions depicting the story of Ganesa's birth in great details (referred further as 'A') (Pl. l) while other one has only 10 medallions painted only with the events of the story (referred later as 'B') (Pl. 2). Both are rectangular in shape, but different on top. Door 'A' has semi-circular top, door 'B' has flat top. In the centre of both the doors elephant headed Ganesa is presented in a dancing pose under pyramidal shaped sikhar of a shrine. It is surrounded by medallions which are painted with the scenes related to the birth story of Ganesa On door 'A' six armed Ganesa is shown dancing on a lotus pedestal. He is carrying a rosary, ankusa, broken tooth and modaka. In the upper pair of hands he holds a snake forming a sort of canopy over his head. The Ganesa of door 'B' is only four armed. Rosary is replaced by the snake here. Both the images of Ganesa are highly bejewelled and dressed in yellow dhoti and his vahana rat is shown near by the row of animals, as elephant and deer. Floral motifs and geometric patterns are beautifully painted in both the doors. While painting these doors artists have followed the version of Ganesa's birth mentioned in Siva Purana. The story starts from the top centre medallion in door 'A'. First three roundels present the general scenes showing Parvati and Siva standing on the mount Kailas in their usual abode. However, the door 'B' presents only one roundel, with the theme here. They are shown in front of a beautiful house. The fourth medallion of the door 'A' depicts Narada visiting Parvati. But this theme describes slightly later in medallion three of door 'B'. The actual story of the Ganesa's birth starts from the fifth medallion where Parvati is shown busy in modelling a child out of her toilet paste. She is assisted by her maid. In door 'B' this important event is absent. Parvati seated with her baby boy blessed by Lord Visnu standing nearby is the theme of roundel two. This is depicted in sixth roundel of door 'A' also, where Parvati is standing with her baby in front of Lord Visnu. In the seventh medallion of door 'A' child is shown paying respect to his mother by touching her feet. The next roundel presents Parvati seated in a cane in anjali mudra. The next two scenes, the most important ones in the story, are common in both the doors. In first scene child is depicted with staff in the hand, guarding the door and stopping even the Siva's entry into the house. (Pl. No. 3) (details of door B). This makes Siva furious and later on he enters into hot arguments. The next part of the story, when the maid informs Parvati, who was curious to know about the happening of outside, is depicted in the following roundel of door-'A', The story is further carried out in the 12th roundel of door 'As, where Narada and Siva are standing face to face. Perhaps this represents the moment when Narada asked Siva regarding the happenings and started praising Ganesa (as mentioned Siva Purana). However, this theme is slightly varied in 6th roundel of door 'B' where Visnu and Narada are shown discussing. In the 13th roundel of door 'N Siva is ordering his Ganas for fighting with Parvati's Gana. And the most interesting part in this, is Parvati's maid appears again in the following scene conveying the approval of Parvati to Ganesa for his deeds as narrated in Siva Purana also. The next part of the story was taken by both the artists of door 'A' and 'B' where both the parties (Siva's and Parvati's Ganas) are arguing amongst themselves as mentioned in Siva Purana. Battle was fought which ended in Parvati's victory. Siva-Ganas returned back to their master with lowered heads and this forms the scene of roundel 16th in door 'A'. As mentioned in the Siva-Purana. Visnu and Siva are shown discussing in the next roundel This theme has been depicted on the door ‘B’ too. Siva Purana and Skanda Purana refer that at last to end the struggle Siva decided to cut-off the head of Gana and it is truly represented in both the doors. Parvati and her maid are shown paying respect to Lord Siva in the roundel of door 'A'. In the next roundel Parvati is shown seated in a sad mood because of her son's death and Siva is shown ordering his Ganas. For the point of identification of textual reference these scenes are the most important as they give the clue that this story is based on Siva Purana only. Skanda Purana refers that after the cutting off the head of Parvati's Gana Siva fought with Gaja-sura and brought his head and fixed to the child. But in the Siva-Purana the Ganas who on the command of Siva went to the northern direction and brought the head of single tusked elephant whom they met first in the direction and this forms the subject of 22nd roundel. In the next roundel, Siva is shown fixing the head of elephant on the baby body. However, in door 'B' all these episodes are missing and in the end both the doors present Ganesa seated with his parent. From the above representation it can be clearly concluded that the artist of the door 'A' was fully aware of the story of Siva Purana while the artist of door 'B' either has the vague idea of the story or he was under the restriction with the limitation of space. These types of doors were made for temples as well as for palaces also under the traditional art of Orissa. This art of painting the wooden doors and Patachitra is mostly practiced in the states of Sonepur and Ranpur. Usually painters prepare the background by coating it with a mixture of chalk and gum made from tamarind seeds. This mixture gives the surface a leathery quality on which the artist paints freely with colours made from various types of clay and stones. For example red colour from Hingala stone, white from Sankha, yellow from Hartala, blue from blue stone and black from the domestic soot. So this pictorial conception of art has special and peculiar forms and types evolved by the native Orissan genius. REFERENCES

- Besides the doors, which is the theme of this paper, one four feet high ivory tusk is also carved with the same theme of Ganesa's birth story in small 36 scenes. This marvellous piece of art is the property of the Mess. Handicrafts Board. New Delhi. This tusk has been published by Mrs. K. Lal for U.S.S.R., Festival of India Catalogue, New Delhi. 1987. PI No. 86.

- Siva-Purana, ed. J.L. Shastri, Vol. II, Rudrasamhita, ch. 13-17.

- Brahmavaivarta Parana, Baburam Upadhaya, 1981, Prayag, ch. 8-12, pp. 674-697.

- Linga Purana, ed. J.L. Shastri. Part 11, Vol.6, ch. 103, pp. 576-579.

- Matyasa Purana Kalyana, 1985, ch. 154, pp. 643-644. Padma Purana ed : J.L. Shastri. ch.1 (Shrsti Khanda)

- Kalyana's Devata Anka, Gita press

- Siva Purana, ed. J.L. Shastri. Vol. II Rudrasamhita 17

- In Mukteshvar of Bhuvneswar. there is an old and beautiful temple of Lord Ganesa which was built in between 800-1060 A.D. It has an image of eight armed dancing Ganesa. He also holds the snake in the same manner. Kalvana's Ganesa Anka, 1974, pp. 445.

- May be artist does not want to paint the toilet scene or it can be local variation also.

- May, Sept. 55, Ancient Arts and Crafts in Orissa, by P.S.R. Sharms. pp. 73.

- Indian Crafts, D.N. Saraf, Delhi. 82' pp. 54-55.

- This was told by the Pata-Chitra artist of Orissa who came to New Delhi for their skill demonstration.

- Siva-Parvati are standing in abode in a garden.

- Parvati is seating near Siva.

- Parvati is in Anjali Mudra seated in front of Siva.

- Parvati is seated in a sad mood and Narad is standing in front of her.

- Parvati is standing with her baby and her maid standing at her back.

- Parvati is standing with her baby and lord Visnu standing in front of her.

- Baby is touching Parvati's feet.

- Parvati is seating in Anjali mudra in a cave.

- Baby is standing outside the cave.

- Siva being stopped by the baby for entering the cave.

- Parvati is being told by her maid inside the cave.

- Siva is seated on a rock and Narada standing in front of him.

- Siva ordering his Gana.

- Maid is talking to the Gana.

- Battle scene.

- Siva Gana are standing with the lowered head in front of their master.

- Siva and Visnu are discussing.

- Siva and Parvati's Gana's fighting.

- Maid is praying Siva.

- Parvati is touching the feet of Siva.

- Parvati is seating in sad mood and Siva ordering his Ganas

- Ganas bringing the elephant head.

- Siva is fixing the elephant head on the Parvati's Gana.

- Ganesa is seating with his parents.

- Siva is standing and Parvati seating in Anjali mudra in front of a house.

- Parvati is seated with a baby in her lap and Visnu standing.

- Parvati and Narad are standing.

- Parvati's Gana is guarding and her maid seating inside the cave.

- Siva being stopped by the Gana into the cave.

- Narada and Visnu are standing.

- Siva's and Parvati's Ganas are discussing.

- Siva is in attacking pose.

- Parvati is seating with a head-less child and Siva standing in front of her.

- Ganesa is seated with her parents.

Destruction of her murals shows the rot in the museum.

The mindless destruction of Ganga Devi’s extraordinary last works at the Crafts Museum is terribly sad. It highlights the caste system between art and craft, the indifference to the creative integrity of a craftsperson’s vision. The quoted reaction of a Crafts Museum official, “Don’t worry, I’ll get another kohbar ghar painted” shows that, even for someone who claims to have worked there for 30 years, one piece of craft is much like another. So Ganga Devi is no more, let’s get Sita Devi or Champa Devi or Ambika Devi.

It’s all Madhubani after all, so what’s the difference? There was an eerily similar response when rumours of the transformation of the Crafts Museum into a Hastkala Academy evoked a public outcry. “Why the fuss? Nothing much happens in the Craft Museum,” was one bureaucrat’s reaction.

Typical is the lack of communication and consultation. Bureaucrats naturally cannot be experts in everything. They need inputs from specialists. Earlier, there was always a process of consultation. When new schemes were being planned, when changes in an established institution or practice were contemplated, when programmes needed evaluation, a committee or working group would be set up, consisting of a cross-section of experts — representative, knowledgeable, and hopefully objective. If there was occasionally too much talk and not enough action, there was at least informed debate.

These days, this interaction with civil society is simply not happening. Ad hoc decisions are taken and no one knows how and why.

Occasionally there’s a political agenda but often (as in the case of the Ganga Devi murals, I suspect) the people involved are neither wilfully wicked, nor have axes to grind. They simply don’t know much about the matter and take knee-jerk decisions without asking anyone or thinking them through. Whether it’s building a six-storey glass and concrete building next to a heritage site, changing handloom policy, withdrawing Delhi’s bid to be a Unesco Heritage City, deciding who is to head a prestigious cultural institution, or even renaming a road, neither legalities nor long-term implications are considered. Things are decided by a few individuals who then become defensive and surprised at the ensuing outcry. Not rolling back the decision becomes a matter of prestige.

To return to the Ganga Devi murals, the present head says the decision was taken before her tenure, and the former director, Ruchira Ghose, says that though the space certainly needed major repairs, the destruction of the artworks was done after she left. Since I myself was on the museum rejuvenation committee previously, I can vouch that though we all agreed that the building urgently needed restoration and upgrading, destroying existing parts of the collections was nowhere on the agenda. The murals could have been restored. Intach performs miracles. There is a paradox here, however. The cost of proper professional restoration is considerably more than a Madhubani craftswoman would receive for an original painting. Restoration is seen as a 21st-century technical skill, Madhubani, a rural “handicraft”. No surprise it was decided to simply paint over the pieces. Unfortunately, we were not consulted. The last meeting I attended was in mid-2014.

At that time, slabs of plaster were falling dangerously from ceilings supported by wooden struts, the godowns which housed the priceless reserve collections were seeping damp and mildew, the galleries had no temperature or humidity controls.

We were all ecstatic that the long-delayed funding had finally come through, and that the museum would be brought to international standards.

In the last six months, media reports and rumours about the future of the Crafts Museum and its amalgamation into a Hastkala Academy began circulating. No one in the sector was informed or consulted. Ministry officials were tight-lipped, saying only that “the status of the Crafts Museum would remain unchanged”. Why can’t we know what’s planned for its future?

When the prime minister talks of Make in India and Skill India, he should rcall those amazing undervalued skills we already have. Let’s not demolish them in our haste to acquire new ones.

The mindless destruction of Ganga Devi’s extraordinary last works at the Crafts Museum is terribly sad. It highlights the caste system between art and craft, the indifference to the creative integrity of a craftsperson’s vision. The quoted reaction of a Crafts Museum official, “Don’t worry, I’ll get another kohbar ghar painted” shows that, even for someone who claims to have worked there for 30 years, one piece of craft is much like another. So Ganga Devi is no more, let’s get Sita Devi or Champa Devi or Ambika Devi.

It’s all Madhubani after all, so what’s the difference? There was an eerily similar response when rumours of the transformation of the Crafts Museum into a Hastkala Academy evoked a public outcry. “Why the fuss? Nothing much happens in the Craft Museum,” was one bureaucrat’s reaction.

Typical is the lack of communication and consultation. Bureaucrats naturally cannot be experts in everything. They need inputs from specialists. Earlier, there was always a process of consultation. When new schemes were being planned, when changes in an established institution or practice were contemplated, when programmes needed evaluation, a committee or working group would be set up, consisting of a cross-section of experts — representative, knowledgeable, and hopefully objective. If there was occasionally too much talk and not enough action, there was at least informed debate.

These days, this interaction with civil society is simply not happening. Ad hoc decisions are taken and no one knows how and why.

Occasionally there’s a political agenda but often (as in the case of the Ganga Devi murals, I suspect) the people involved are neither wilfully wicked, nor have axes to grind. They simply don’t know much about the matter and take knee-jerk decisions without asking anyone or thinking them through. Whether it’s building a six-storey glass and concrete building next to a heritage site, changing handloom policy, withdrawing Delhi’s bid to be a Unesco Heritage City, deciding who is to head a prestigious cultural institution, or even renaming a road, neither legalities nor long-term implications are considered. Things are decided by a few individuals who then become defensive and surprised at the ensuing outcry. Not rolling back the decision becomes a matter of prestige.

To return to the Ganga Devi murals, the present head says the decision was taken before her tenure, and the former director, Ruchira Ghose, says that though the space certainly needed major repairs, the destruction of the artworks was done after she left. Since I myself was on the museum rejuvenation committee previously, I can vouch that though we all agreed that the building urgently needed restoration and upgrading, destroying existing parts of the collections was nowhere on the agenda. The murals could have been restored. Intach performs miracles. There is a paradox here, however. The cost of proper professional restoration is considerably more than a Madhubani craftswoman would receive for an original painting. Restoration is seen as a 21st-century technical skill, Madhubani, a rural “handicraft”. No surprise it was decided to simply paint over the pieces. Unfortunately, we were not consulted. The last meeting I attended was in mid-2014.

At that time, slabs of plaster were falling dangerously from ceilings supported by wooden struts, the godowns which housed the priceless reserve collections were seeping damp and mildew, the galleries had no temperature or humidity controls.

We were all ecstatic that the long-delayed funding had finally come through, and that the museum would be brought to international standards.

In the last six months, media reports and rumours about the future of the Crafts Museum and its amalgamation into a Hastkala Academy began circulating. No one in the sector was informed or consulted. Ministry officials were tight-lipped, saying only that “the status of the Crafts Museum would remain unchanged”. Why can’t we know what’s planned for its future?

When the prime minister talks of Make in India and Skill India, he should rcall those amazing undervalued skills we already have. Let’s not demolish them in our haste to acquire new ones.

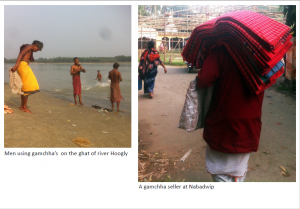

Games are a common passion, a common pastime which cross all sections of the community. Playing or watching games form a highly significant aspect of culture, both because of their importance in peoples lives and their capacity to bring families and communities together and because of the degree of creativity and skill that go into devising them. No indoor games match the passion with which cards are played in India. One such card game, now facing extinction is Ganjifa.

The next, more detailed, reference is found in the Ain-I-Akbari, a book written by Abul Fazl Allami towards the end of the 16th century during the reign of the great Mughal emperor Akbar (1542-1605). Abul Fazl devotes a short chapter to the games - chess and ganjifa - played by Akbar.

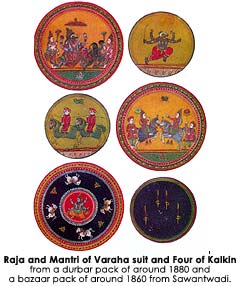

Card playing became very popular and widespread in the 17th and 18th century at the innumerable Indian courts, especially within the zenanas (women's quarters) where Ganjifa was the recourse from institutional boredom. With rising popularity it became the subject of much writing and beautiful decks were created for the nobility made of ivory or tortoise shell inlaid with precious stones (called darbar kalam). But the game was so popular it spread among the common people, who used cheaper sets made from wood, palm leaf, pasteboard, and various other inexpensive materials (called bazaar kalam).

The game spread with the expansion of the Mughal Empire. The Deccan belt, with its intermingling of North and South, Hindu and Muslim cultures became fertile ground for the development of a variety of games and cards. The hinduization of Ganjifa cards contributed to their spread and popularity and was played in Rajasthan, Bengal, Nepal, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Karnataka.

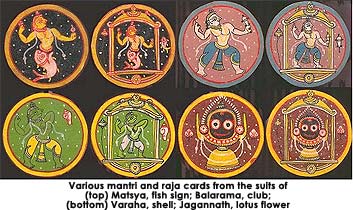

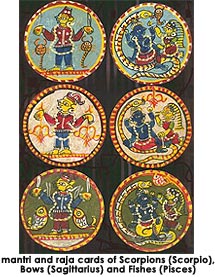

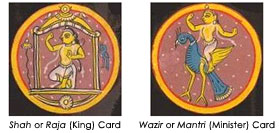

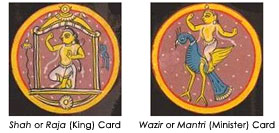

The practice and the rules of the game, played for centuries in India - across palaces and hovels - is now almost wiped out replaced, we hope not irrevocably, by the western import of the 52 set game. These cards, now curiosity items for tourist, are still hand-made and hand-painted by skilled craftsmen (chitrakara). Therefore, each deck is a truly unique item. Despite the many changes, the general structure of any Ganjifa deck is not really different from other kinds of pattern. The suits are always made of twelve subjects, whose backgrounds are colored. Their values include pip cards running from 1 (or ace) to 10, and two courts: a minister (or counsellor) and a king.

Despite the many changes, the general structure of any Ganjifa deck is not really different from other kinds of pattern. The suits are always made of twelve subjects, whose backgrounds are colored. Their values include pip cards running from 1 (or ace) to 10, and two courts: a minister (or counsellor) and a king.

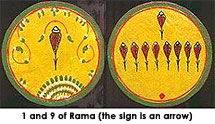

The pips are small suit signs, more or less stylized, arranged in patterns of various fashion, a free choice of the artist who painted the deck, though often influenced by the regional trend.

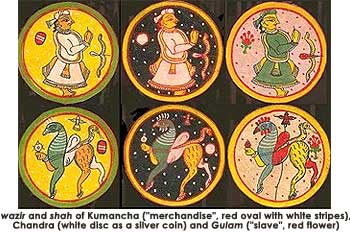

The illustrations depict human figures and incarnations of many Indian divinities, posing in different attitudes, that change in accordance with the pattern of the deck and with the regional custom. Ganjifa packs that come from the same area not only have similar illustrations but matching backgrounds too, differing from those of decks made elsewhere. The use of different background colors for identifying the suits of the deck was once found also in the other variety of traditional Persian cards, the As-Nas, now extinct. The geographic origin of a deck affects its background colors, one different for each suit, thus alternative names for Ganjifa decks, according to how many suits they have, are atharangi ("eight colours"), navarangi ("nine colours"), dasarangi ("ten colours"), baraharangi ("twelve colours"), and so on. In patterns with more than eight suits, some colors may appear similar, but in this case the rim, clearly different, provides an easy reference.● Mughal Ganjifa

This style of Ganjifa was created and used by the Mughal courts and among the known patterns is probably the variety closest to the original pattern once used in Persia.

It has 96 cards divided into eight suits. The court cards are usually referred to with their old names: wazir (the minister), while the king is called shah (also padishah, or mir, probably short for amir).

In most parts of India, the wazir and shah subjects feature human figures (the king either seated on a throne or under a canopy, the minister often mounted, with or without his retinue). But in decks made in Odisha they are replaced by characters of the local mythology and religion.● Dasavatar Ganjifa

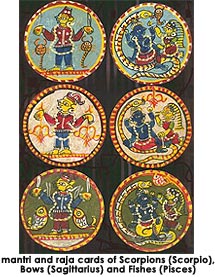

Although the game played with Ganjifa cards flourished among the Mughals in its 8-suited version, the Hindu players felt the need of a scheme somewhat closer to their homeland traditions. Therefore, they sought inspiration in themes borrowed from the local religion for illustrating the court cards, and creating their own suit signs.

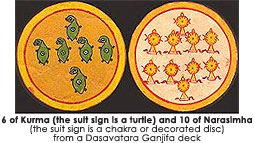

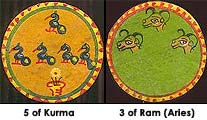

The main non-Mughal Ganjifa pattern is the Dasavatara. This word literally means "ten incarnations", referring to the human and animal appearances traditionally chosen by god Vishnu for revealing himself, in opposition to evil.

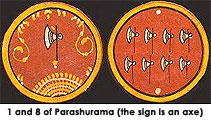

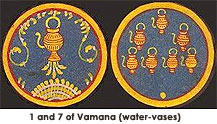

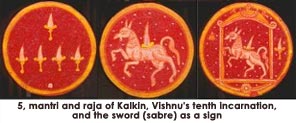

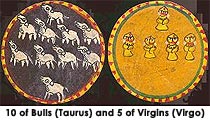

Such incarnations, usually ten but sometimes more, according to the local beliefs, are as follows: Matsya (fish), Kurma (tortoise) Varaha (boar), Narasimha (half man, half lion), Vamana (dwarf), Parashurama (Rama with an axe), Rama (hero of the Ramayana), Krishna, Buddha and Kalkin (the incarnation yet to come)

The number of suits in the Dasavatara Ganjifa are ten (five "strong" and five "weak"), and their signs reflect the features of the religious theme. Eight out of ten suits are standard, found in all decks, while two of them may vary from region to region, chosen among a number of optional ones (see the following table).

However, often Dasavatara Ganjifa decks have more than ten suits: two additional ones are common, but larger sets may count up to 20 or 24 suits (i.e. 240 to 288 cards, a rather unusual composition). Some names of the Dasavatara suits are those of the incarnations to whom they refer, while all the signs are symbols of their feats; besides the customary ones, some alternative signs are sometimes preferred.

Some names of the Dasavatara suits are those of the incarnations to whom they refer, while all the signs are symbols of their feats; besides the customary ones, some alternative signs are sometimes preferred.

| Suit Names (Incarnations) | Suit Signs (alternatives shown in square brackets) |

| Bishbar suits | |

|

Parashurama

Rama

Kalkin

Balarama (optional)

Buddha (optional)

Jagannath (optional)

Krishna (optional) |

axe

monkey [ bow and arrow ] [ arrow ]

sword [ horse ] [ parasol ]

plough [ club ] [ cow ]

shell [ lotus flower ]

lotus flower

cow [ crowned bust ] [ blue child ] [ chakra ] |

| Kambar suits | |

|

Matsya

Kurma

Varaha

Narasimha

Vamana |

fish

turtle

shell

chakra (decorated disc)

jug / vase |

| additional suits (if any) | |

|

Ganesh

Kartikkeya

Brahma

Shiva

Indra

Yama

Hanuman

Garuda

Krishna

Narada |

rat

peacock

vedas (scriptures)

drum

thunderbolt

snake noose

club

small Garuda

flute

vina (Indian lute) |

● Bird Motif Ganjifa

A particular variety of Ganjifa cards is the one in which the ordinary suit signs are replaced by birds (or, more seldom, by other animals too). It is found especially with a Mughal composition, i.e. eight suits. More recently, also a few Dasavatara samples have been made with ten suits, each of which is represented by a different bird; the small flower vase at the base of each pip card is merely decorative.The choice of using birds as suit signs is not terribly surprising, considering the many included in Hindu mythology, among which are the crow (vehicle of Shani), the peacock (vehicle of Kartikkeya), the parrot (vehicle of Kamadeva), the swan (vehicle of Saraswati and Brahma), plus a few mythical creatures such as Garuda (half man and half eagle, vehicle of Vishnu) and Arva (half horse and half bird).

The birds featured in Ganjifa cards (i.e. the pips) are small and rather stylized, but the suits can be told also by the colour of the background, and by the personages of the court cards, who sometimes hold the traditional sign (sword, shell, jug, etc.), or are recognizable by their particular shape.● Other Ganjifas

Besides the Dasavatara and the Mughal Ganjifa (including the "birds" variety), several other patterns exist, yet less common than the two aforesaid ones. They feature specific themes with a various number of suits.

-

Rashi Ganjifa: Rashi (zodiac) Ganjifa is a twelve-suited pattern that features zodiac symbols as suit signs. The Indian or Vedic zodiac is similar to the Western one: it divides the year into twelve periods or "houses", each of which is identified by a symbol.

-

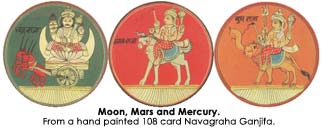

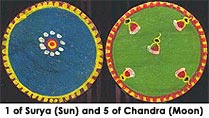

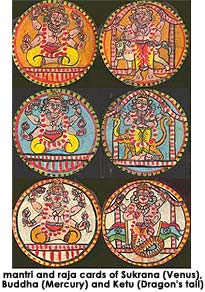

Navagraha Ganjifa: Navagraha means "nine planets". In Hindu culture, these planets are believed to bestow humans with special gifts, and are worshipped as gods (specific prayers are recited to each of them). In India this is an important cult; in fact, the Navagraha Ganjifa pattern was created at the beginning of the 20th century by Shankar Sakharama Hendre, whose project was to sell cards to raise enough money for building a temple dedicated to the Nine Planets, in Bombay. Although his goal was not achieved, the Navagraha Ganjifa survived. In this pattern each suit represents a planet; but the last two, Rahu and Ketu, are actually lunar nodes, namely the ascending node and descending node, respectively referred to as "dragon's head" and "dragon's tail", and often pictured as a bodyless head and a headless body. Each planet is a deity itself, to which a month, a zodiac sign, a color, a gem and a steed are matched.

The full series of planets (some have alternative names, according to the different parts of the country) are: Surya/ Ravi (Sun) on a 7 horse-drawn chariot, Chandra (Moon) on an antelope-drawn chariot, Mangala/ Kuja (Mars) on a buffalo or goat, Budhan/ Buddha (Mercury) on a lion with elephant's trunk, Guru/ Brihaspati (Jupiter) on an elephant or goose, Sukrana/ Sukra (Venus) on a horse, Sani/ Shani (Saturn) on an eagle or crow and Rahu (Dragon's head) and Ketu (Dragon's tail) who have no vehicles.

Besides the Ganjifa varities mentioned so far, some others exist: the Ramayana Ganjifa, a twelve-suited pattern inspired by the Sanskrit epic Ramayana, the Ashtamala Ganjifa, inspired by eight episodes of Krishna's life as a youth, and the Ashtadikpala Ganjifa which refers to the eight cardinal directions.

Ganjifa are traditionally round, measuring approximately from 20 mm to 34 mm to 120 mm in diameter.

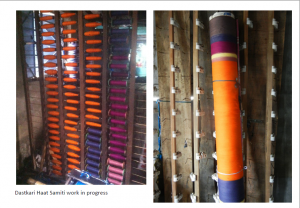

Today Ganjifa cards are made of layers of pressed paper, but in Odisha cloth is still used. At first, paper layers (normally six) are layered and glued together, primed with lime, dried, burnished, cut, painted and lacquered. The lacquer is made from Indian shellac (chapra) or other natural resins which give the cards the required stiffness, protection and smoothness in handling. Cloth cards are made from cotton waste rags, soaked and starched with glue made from tamarind seeds; when dry, by using a mold the starched cloth is cut into discs, two of which are glued together to make individual cards; a paste made from chalk is then applied to make the surface even, and the deck is finally painted. Paints were traditionally made from mineral or vegetable substances are today increasingly replaced by readily available synthetic colors.

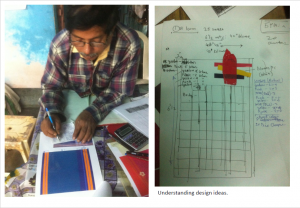

The process of making cards is shared by the entire family of chitrakars. Much of the preparatory work is done by women. Pip cards are painted by junior artists, figure cards by senior ones. They begin on previously prepared colored backgrounds by first outlining the figure in white or lighter colors and then they successively paint the details in different colors finishing the figure with a thin outline in black. Each artist evolves a personal style in spite of his fidelity to traditional conventions.

The cards are painted plain red or orange on the back. Cards from Odisha have yellow, green, blue and black backs and increasingly in recent years, brown backs rendered in cheap paint made from lal mati (red mud). Occasionally one finds the backs decorated with a rim line or small central flower. Fully ornamented backs are rare as the artist has to take special care to make the backs identical so as not to create any tell-tale irregularities. Some decks are housed in a wooden box or case, often decorated with themes consistent with the pack's pattern. Each region has evolved its own distinctive type for instance, in Rajasthan boxes are short and oblong painted predominantly in green or crimson, in Sawantwadi they are cubic are commonly in red, in Andhra Pradesh they are long with bulging sides painted in green, in Mysore they are oblong or cubic, in Odisha cubic in black, brown and yellow and in Kashmir long boxes with floral patterns. The paintings vary from region to region, from floral motifs to elaborate processions. All boxes have a sliding lid.

Some decks are housed in a wooden box or case, often decorated with themes consistent with the pack's pattern. Each region has evolved its own distinctive type for instance, in Rajasthan boxes are short and oblong painted predominantly in green or crimson, in Sawantwadi they are cubic are commonly in red, in Andhra Pradesh they are long with bulging sides painted in green, in Mysore they are oblong or cubic, in Odisha cubic in black, brown and yellow and in Kashmir long boxes with floral patterns. The paintings vary from region to region, from floral motifs to elaborate processions. All boxes have a sliding lid.

Regrettably, due to the lack of request, during the past decades the making of these decks, once a common activity throughout India, has considerably subsided, and is now no longer very common. The game too is certainly endangered, but not extinct, and especially in the state of Odisha the locals are still known to play with Ganjifa sets.

Regrettably, due to the lack of request, during the past decades the making of these decks, once a common activity throughout India, has considerably subsided, and is now no longer very common. The game too is certainly endangered, but not extinct, and especially in the state of Odisha the locals are still known to play with Ganjifa sets.

The main centres of Ganjifa manufacture are Sawai Madhopur and Karauli in Rajasthan, Sheopur in Madhya Pradesh, Fatehpur District in Uttar Pradesh, Sawantwadi in Maharashtra, Balkonda, Nirmal, Bimgal, Kurnol, Nossam, Cuddapah and Kondapalle in Andhra Pradesh, Mysore in Karnataka, Puri, Sonepur, Parlakhemundi, Barapalli, Chikiti and Jayapur in Odisha, Bishnupur in Bengal and Bhaktapur, Bhadbaon and Patan in Nepal.

From this basic play, variations are derived. A univeral characteristic of Ganjifa games, whether played with eight, ten or twelve suits: the two court cards always rank highest in each suit, but in half the suits the numerical cards then rank in one order and the other half in the opposite order. The objective of the game is to win as many tricks as possible.

To a game in which the evocation of "your Rama did this" or "your Matsya lost and my Narasimhan won" was said to remit sins, Ganjifa today is a craft in crisis. In the coming years, unless the cards can make a transition from museum collections to the drawing rooms and card tables, it is an art which will become extinct.

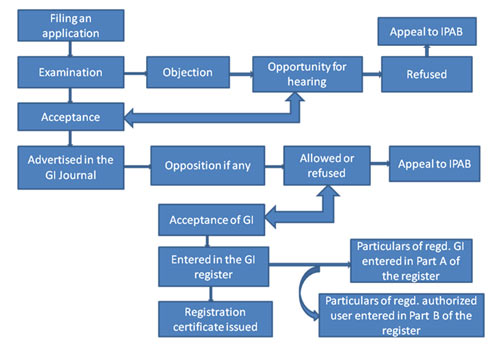

Importance Of GI Registration:

Under the law of Geographical Indications in India, only if a Geographical Indication (hereinafter referred to as, “GI”) is registered in India, then the registration affords legal protection by enabling infringement action possible. Further under the TRIPS Agreement, to which India is one of the signatories, registration in the home country (i.e. country of origin) is a pre-requisite for registration in other member countries.That apart registration enables protection of the GI and its promotion. It confers exclusive right to the producers concerned to produce and market the GI goods. Production and sale by anyone other than the producers concerned is an offence punishable under the GI law.Registration therefore enables the entire world demand to be catered to by the producers concerned as opposed to it being met by the world at large, prior to registration. Therefore registration paves the way for the concerned producers to cater to the entire market demand. It thereby increases the sales of the producers, thereby increasing their turnover and profits. This in turn leads to national development and prosperity. This is also called as the cascading effect of GI registration.Further, GI protection ensures that the consumers get only original GI goods from the place of origin, thereby preventing them from deception and ensuring originality. It forms the basis for initiating infringing action, and to curb piracy and entry of spurious goods into the market.

What Could Be Protected?

A name or a figurative or geographical representation or any combination of them suggesting the geographical origin of goods to which it applies can be protected as a GI in IndiaExample: Pochampally Ikat, Sri Kalahasti Kalamkari, Kashmir Pashmina, Kashmir Sozani, Muga Silk & Madhubani Paintings, Sikki Grass Products of Bihar.Who Is Entitled To Seek Protection Of A GI?

Any association of person or producers or any organization or authority established by or under any law and which represents the interests of the producers concerned is entitled to file an application for registering the GI concerned.Example:

|