JOURNAL ARCHIVE

Raghunath Nama A spirit of innovation, a desire to combine all the traditional printing processes of India. To keep up with the hand printing and dyeing practices and along with small machine makers create equipment which would remove the dreary and harmful processes involved in printing and dyeing.

Mr. Jon Randall, who happened to find Raja ravi Varma playing cards during one of his purchases of old playing cards at an auction house in the U.K. was generous enough to add some significant insights as well as scanned images of the cards to Mr. Gordhandas' article on 'Playing Cards by Raja Ravi Varma.'- Asia InCH

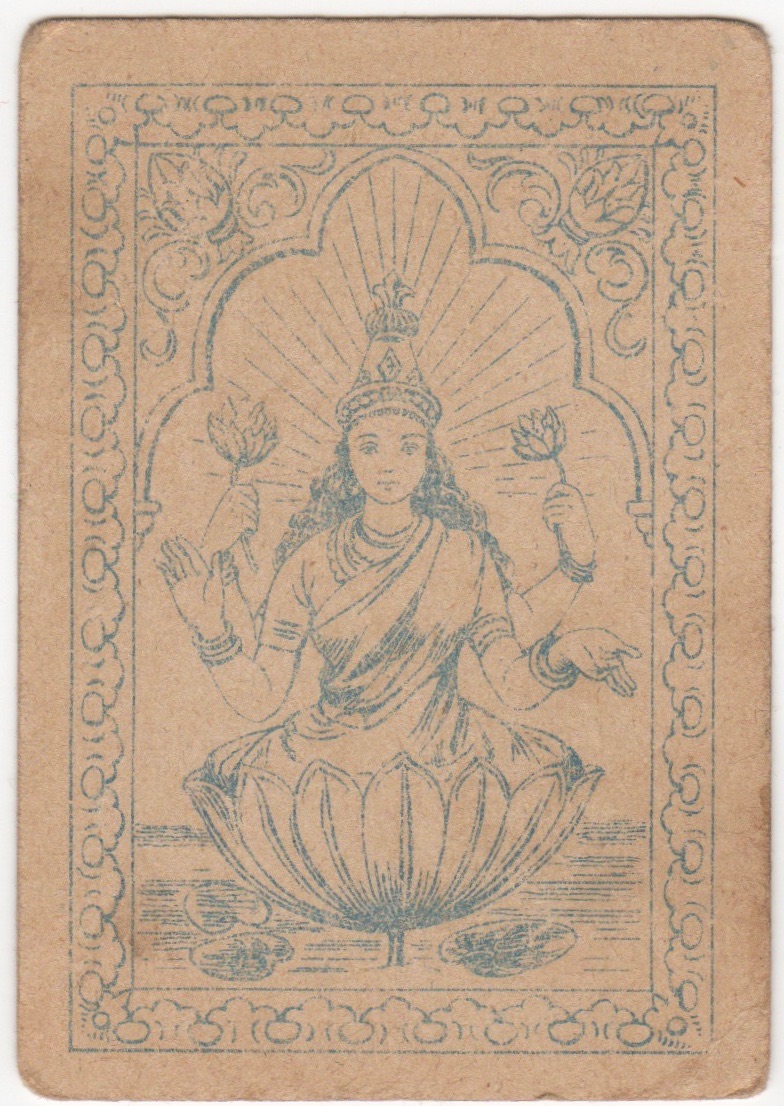

On purchasing a lot of ‘old playing cards’ at an auction house in the U.K. I was aware the lot included a mix of cards, some with Indian court cards, but having arrived late I was more concerned with checking out the French cards in the lot that had initially attracted me. The lot cost more than anticipated, but I was a happy man carrying a small box of cards to my car. Instead of tackling the 2 hour drive home immediately I eagerly looked through every card and sorted the packs out correctly. I’d not noticed the Ace of Spades to the Indian pack in my brief viewing of the lot prior to the auction ... Ravi Varma Press, Bombay. Interesting I thought, a new name to me and one of only a handful of Indian packs I’d seen. Amongst the mix of cards in my box I sorted one complete pack with an elephant on the back of the cards, it includes the joker and is in excellent condition, 11 cards (3S - KS) of the same court and back design in more used condition, another pack missing the 8H and including several faults with different court cards and an Indian girl as the back design, and a single pip card (6H) with a 3rd different back design of what to me looks like an Indian deity sitting in a flower.

At home a couple of evenings later I thought I’d research my new Ravi Varma Press playing cards. Search pretty much anything and Google will spit out multiple related hits. Not so with Ravi Varma Press playing cards. One solitary hit ... an article written by Kishor Gordhandas on craftrevival.org (there are now two hits, the other a US forum post in search of information on RVP playing cards).

With great interest I read the article, re-reading the final paragraphs a few times to fully digest them. As it sank in that RVP playing cards were incredibly scarce, I became excited to contact Mr Gordhandas and inform him that I had a complete RVP pack with different court cards to the Mythological and to the Historical packs illustrated on the website. Both the Mythological and the Historical packs have rounded corners, yet this ‘new’ pack of mine has square corners, leading me to believe this ‘new’ pack is actually older than the two known packs. The AS is also a different design, similar to the Historical pack, but with quite a few differences.

The court cards are not named, and my knowledge of historical India does not extend to identifying the significant characters that adorn this pack. I welcome any information or lead a keen reader may wish to pass my way regarding the possible names of those depicted on the court cards or regarding the general history of Ravi Varma Press playing cards I believe the article was written in 2008, and I was saddened to learn that Mr Gordhandas had passed away the following year. I feel from reading the article that he would’ve been delighted to see these cards of mine. It is my pleasure to add this short text together with comprehensive scans of the my RVP cards to the webpage started by Mr Gordhandas.

The artistic zeal and passion of Rajasthani artisans have always shown great respect to 'God' and 'Nature', which had inspired them to convert the harsh environmental conditions of the region into the world of colours. The painting canvas of the Rajasthani painters is very vast extending from havelis, palaces, forts to temples. These paintings are the real reflection of Rajasthani culture. Several subjects from the religious to secular and scenes from court life to hunting seens have been painted by the miniature painting artists, who have worked in various courts of Rajasthan. There are many prominent courts such as Mewar, Bundi, Kota. Bikaner, Marwar, Kishangarh and Jaipur where the tradition of painting was encouraged and patronized. Each of these centers has the distinct characteristics, reflected in their miniatures painting schools. These have been studied by several scholars.' The painting tradition in Rajasthan is not restricted to the miniature paintings on paper only, rather it has been practiced extensively on diverse mediums i.e. wall, cloth, wood, leather, marble etc.' Rajasthani paintings on wood, like any other medium, also illustrates an interesting and fascinating aspect of their indigenous styles. This has been less studied and published so far in comparison to miniature painting. These artefacts are from architectural panels to everyday objects of utility. The main thrust of the paper is to discuss some of the beautiful paintings on various wooden artefacts preserved in the collection of National Museum, New Delhi. Before going in detail, a brief survey of the carpenter and painter community will be undertaken. Khati and Suthar The khati and suthar community in Rajasthan are mainly involved in the mending of carts and all agricultural implements, however many times they are agriculturists also.' They claim to be the descendants of Vishvakarma, the celestial architect. The word suthar comes from Sanskrit word saatradhara. In Marwar, the term khati is commonly used for suthar, this seems to have derived from word kath, which refers to wood. In some districts khati is known as suthar, which are based on the particular kind of articles made or mended by these groups, where they reside and work. Traditionally khati and suthar do not intermarry and try to maintain their caste sensitivity. The Brahma Purana mentions that the suthars are said to be the offspring of Visvakarma and wood carpentry is their main occupation. The suthar community is distributed in many parts of Rajasthan, with a large concentration in and around Udaipur. In the suthar community, Vishvakarma has a special place, as they belief their origin back to this god and they also worship Ganesha, Amba, Lakshmi, Hanuman and other Hindu deities. They have an expert knowledge about carpentry from their childhood, as they get trained by observing their elders in these traditional craft. They share the regional trend in oral tradition and folk songs with the other communities. Bhats (local singers) praise the wood craftsmen in their singing: "If khati does not create plough, how would we get grains If they do not make the axis of chakki how would we get ground ata If they do not make khat we have to sleep on the floor; " etc. Chiteraas and Chejaraas

Apart from the strong presence of the khati and suthar community in Rajasthan, there were the chiteraas and chejaraas also and often they work together to carve or paint the palaces, temples and houses in the region. The fresco painting artists were called chiteraas (painters) and the chejaraas (masons), since they work both as painters and builders.

Pl.12.1: (from left to right) upper row; orange chapdi (orange lac) ; lower row; yellow clay (peeli mitti) ; chalk powder (khadiya mitti)

Pl.12.2: Micro photo of panels back showing a primer layer of yellow mitti with orange chapdi

The wood has to be prepared first, before painting, by coating a primer layer of lac and clay. The two types of lac are orange chapdi (orange or light golden lac) or black chapdi (black lac) is usually used while giving the primer coating on the desired panel or surface. Lac is not used alone; the yellow clay (peeli mitti) or chalk powder (khadiya-mitti) is mixed (Plate12.1). For preparing the peeli mitti paste, water and chapdi with spirit is mixed. For making the khadiya mttii paste, water and linseed oil or edible oil is mixed. These two things were mix together and then rubbed on to the wood directly with a cloth (Plate 12.2). Once the surface is dried, it is burnished to achieve the even surface. When the smooth background is ready the chetaras first use to do the line drawing and then the painting. Artists use only natural colours for their art work, for example lamp black (kajal) is used for black, lime (safeda) is for white, indigo (neel) for blue, red stone powder (geru) for red, saffron (kesar) for orange, yellow clay (pevri) for yellow ochre and so on. These natural colours are mixed in limewater and used for painting. They remained vibrant for almost as long as the building lasted.' Some of these examples are evident in wood panels of the museum collection. Rajasthani Wood Carvings The wood carving collection in the Decorative Arts Department of the National Museum, New Delhi is rich and vibrant. It has different type of artifacts such as portions of architectural dwelling, door, window, temple chariot, deities' vehicles used for temple procession, temple mandapa, palanquin, swing, screen, panel(s) depicting Hindu deities, floral patterns and utilitarian objects. These artifacts are intricately carved in round and in bold or shallow relief. Many of these are decorated in colourful ways, besides inlay ornamentation. These wooden artifacts were crafted at various centers i.e. Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat and Rajasthan. Among all these centers, the collection of Rajasthani wood carvings is significant in many ways. As these artifacts show the different categories like architectural dwellings to utilitarian objects, which portray vivid subjects such as from religious to secular and were adorn with various techniques i.e. carving, painted' and painting'. The first two techniques are prevalent in many other production centers, but painting tradition has been persuaded by the Rajasthani artists in a remarkable and unique manner. Miniature painters of Marwar, Bikanar, Kotah, Jaipur schools have done the painting on wooden artifacts also, besides the paper painting. Artifacts of the architectural dwelling, palanquin, mirror, decorative panels, cot and throne legs, boxes, ganjifa cards and yoyos were adorned with beautiful paintings in around 18th to 19th century. The few wooden objects ornate with excellent paintings will be discussed in detail here.The first group discussed here is of five long architectural panels, which illustrates the painting in Marwar/ Bikaner style of 18th - 19th century. These panels depict popular genres and themes of Rajasthani miniature paintings such as Ragamala, Ganesha-Durga, Dhola-Maru, Krishna-Brahma and Hunting scene. All the paintings are executed in colourful manner on the red background except for the last one, which is on the black background. These panels appear to be from the upper portion of the door or window frame as the orientation of scenes in all the panels is horizontal. More importantly the narrow sockets on both the end panels are to fix the vertical panels or pillars, so that chauket (frame) of door or window should be properly completed.

Pl.12.3: Architectural panel depicting Ragas and Raginis, marwar, Rajasthan, 18th century, 76,485

Pl.12.4: Architectural panel illustrating goddesses queen Sraswati, Lord Ganesha and Durga Marwar, Rajasthan, 18th-19th century, 76,654

Pl.12.5: Architectural panel depicting the Dhola-Maru style Marwar/Bikaner School, Rajasthan, 18th -19th century, 76,695

The unique subject of 'Ragamala', the garland of Raga, is an interesting form of art that combines poetry and print to convey the mood of a melody.' This subject gained momentum in the early 17th century CE as miniature artists of Kotah, Bikanar, Jodhpur and Jaipur School had portrayed this subject extensively. Some of the raga-ragini themes are painted here in the first panel. (Plate 12.3) The panel depicts the concept of raga-raginis within the backdrop of within a temple, forest or an architectural setting depending upon the subject of the theme. Trees and architecture have been further used to divide the scenes. Illustration starts (from left to right) with the morning ragas, Bhairav raga, Kambati or Kambavati ragini, Ramkali ragini, Varari ragini, Maru ragini, Asavari ragini, Deshkhar raga and Nata raga." All the human figures are rendered with big eyes, sharp nose, broad forehead and wear traditional attires. The architectural pavilion, carpet, floor covering indicate that probably it was commissioned by royalty. The salient features of Marwari style painting of 18th century such as, well-built human figures marked with regional features and the blue-white clouds. The next panel illustrates Lord Ganesha in the center and queen /goddesses on throne i.e. Saraswati on a swan and Durga on a lion are seen on either side (Plate 12.4). Prominent depiction of trees, as dividers, full of leaves, fruits and birds make the entire composition very attractive. All the deities are adorned with colourful traditional Rajasthani outfit and lots ofjewellery and crown. A four armed Ganesh sits cross-legged on floral patterned carpet and holds a battle-axe/elephant goad (ankush), rosary and a bowl of sweets (modaka). Female devotees hold flywhisk (chauri), men standing in salutation gesture (anjali mudra) and children are seen standing around the deity. A four armed Durga is seen riding a lion, which moves majestically towards the center deity. She holds a sword, trident, umbrella (chhatra) and a disc (chakra). Goddess Durga is flanked by the trumpet bearer and the flag bearer. A four armed Saraswati sits on a swan facing Ganesha. She holds a book and a veena in her hands. A similar compositions depicting Ganesha and Saraswati in the grove are also seen in Marwar paintings.' Well dressed, crowned, two armed queen /goddess sits on throne. She is surrounded by four female devotees, who are paying homage to her. Sharp facial features, big eyes, broad forehead, proportionate bodies of all figures indicate their close resemblance of Marwar School made in the late 18th -19th century. This is a rare 19th century painting now housed in the Mehrangarh Museum Trust. Dhola-Maru, the famous love story of Rajasthan, is narrated in the third panel (Plate 12.5). Dhola-Maru, on a camel are moving towards the palace, which is being guarded by the watchmen. They are being chased by warriors, who are riding on horses and holding swords, spears and shields. The most interesting feature here is the depiction of desert topography shown along with trees in proper prospective. Such narration is often illustrated in the Rajasthani miniature painting as well. Composition of the theme includes, Dhola-Maru being chased by warriors while the pictorial divisions are added with trees. Illustration of human and animal figures and their facial features, their body movements etc, are quite close to Marwar/Bikaner school miniature painting tradition made around 18th - 19th century. The fourth panel portrays the most popular sport of Rajasthan royalty. This panel depicts the well dressed Rajasthani warriors in different groups, as riders on horses and elephants who are fighting and hunting (Plate 12.6). The lion hunters are using various kinds of weapons i.e. a bow, gun, sword, dagger and shield. The most interesting feature is the gunmen using two legged gun-stand, placed on the ground, for shooting the lion. The various animals like horses, lion, dogs, the jewelled elephant, and the movement of horse and lion is well illustrated in the panel. Such scenes are quite often seen in the Marwar/Bikaner school miniature paintings made around 19'h century.

Pl.12.6: Architectural panel illustrating a hunting scene marwar/bikaner, Rajasthan, 18th-19th century 76.486

Pl.12.7: Architectural panel depicting Lord Krishna and Brahma with Devotees, Bikaner, Rajasthan, 18th century 77.188

In the next panel of this group, Lord Krishna and Brahma are surrounded by attendants (Plate 12.7). Krishna stands under a tree playing his flute which everyone is enjoying and even the cows are looking at him affectionately. Brahma sits on the throne flanked by the chauri bearers and devotees on either side. Both the Lords are dressed in yellow dhotis, while devotees are in usual Rajasthani outfits. All the figures are slightly elongated, yet the facial features are prominent and resemble the Bikaner style of Rajasthani painting of the 18th century.The next important object with a colourful and vibrant theme is a rectangular wooden mirror frame. The frame of the mirror, on both sides of the lid with a metal sheet as a back covering and richly adorned with beautiful paintings (Plate 12.8). The subject remains the same - Hindu deities, portrayal of women and floral arrangement. Such mirrors are usually fixed on the walls in palaces or forts of Rajasthan. Covering the mirror is an ancient belief in many communities in India, so that it should be protected from evil. Often people use to cover their mirrors either with a fabric cover or with a wooden lid, which was sometimes decorated with beautiful paintings as also seen in this object.

Pl.12.8: Rectangular mirror with paintings Bikaner/Marwar paintings with Nathwara style, Rajasthan, 19th century

The front of the lid illustrates five pairs of Krishna-gopis' raasalila around Ganesha, who sits in the center. Four armed Lord Ganesha holds a sweet (modak), lotus, elephant noose and beaded string. The crowned and bejewlled Ganesha has a halo and is dressed in yellow dhoti. He sits on a throne, which has a parasol (chhatra) covering; such a depiction is often seen in the Bikaner, Jodhpur and Jaipur style of miniature paintings. 1' Krishna and gopis are dancing with daandiya (dancing sticks) and are shown holding various musical instruments such as the dholaka, and manjira. The gopis are dressed in orange and green lehenga (long skirt), yellow choli (blouse or upper garment), orange odhani (head covering). On the reverse side of the lid, there is a royal portraiture of a Rajasthani lady on a bright orange background decorated with floral borders (Plate 12.9). She is dressed in an orange lehenga, a maroon choli and a green odhani along with a borlajhumar (head ornament), pair of long ear rings, many necklaces and bangles. These features indicate a blend of Bikaner and Marwar miniature paintings with the Nathdwara style of early 19th century paintings.

Pl.12.9: Portrait of lady, Bikaner, Marwar painting with Nathwara style, Rajasthan, 19th century

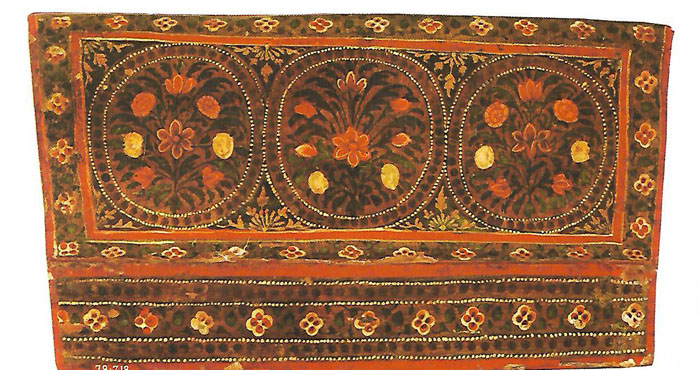

Two small wooden boxes of rectangular and octagonal shapes are the next objects of discussion, which illustrates an interesting example of 20th century folk style painting. Some of the popular Rajasthani subjects have been illustrated on a brown and red background. The rectangular box has three inner divisions which gives the impression that it could also be a scribe box. It depicts the story of Laila-Majnu on a brown background (Plate 12.10). The outer case of the box depicts Laila-Majnu, wherein a man in a garden is shown smoking a huqqa along with an another horse rider and a camel rider, while the top portion shows a man, probably Majnu, resting with a women, perhaps Laila, while other warriors are about to attack them. The octagonal box has small in-built legs with religious motifs such as a rosary, holy books etc. (Plate 12.11). Depiction of Lord Shiva, Ganesha, Vaman, the scene of samundra- manthan and courtly scenes are depicted all around the box. The lid of the box depicts the scene of Krishna steeling butter from the gopis. Group of three small size fragmentary panels are the last one to be discussed in this paper, which could be from Marwar or Jaipur School probably dated to late 18th to early 19th century. These panels depict floral patterns rendered in naturalistic manner on a black or golden background. Colourful flowers, arranged in rows are beautifully portrayed in these panels. Such flower buties are very common in borders of Rajasthani miniature paintings and in printed textiles. These panels could be a part of a palanquin seat or a throne as it appears on one side of the panel, which has a decoration on both the sides and is slightly curved from the center (Plate 12.12). The small surface of the rectangular panel painting is composed of two parts, broad upper and lower narrow portions. One side of the upper portion depicts three men hunting a lion within an oval frame, which is further encased within rectangular double borders of red colour and floral creepers in between. The other side is decorated with three roundels set within rectangular frames, arranged in a row. A similar kind of a floral composition within roundels is seen on one of the side panels of Raja Man-Singh's throne depicted in a famous painting of Raja Man Singh's raj tilak (coronation ceremony). This painting depicts the coronation ceremony of Raja Man Singh, which took place in 1804 CE and is housed in the Mehrangarh Museum Trust. Painted by the court painter Amar Das, it shows Raja Man Singh sitting on a golden throne in an open courtyard under a canopy surrounded by courtiers and women. The lower narrow portions, of both the sides, illustrate small red-white flower buties with green floral creepers on golden background. This portion was probably fixed on the side frame of the throne.Panels, mirrors, boxes all these paintings show the colourful and lively illustration of painting of Marwar, Bikaner and Jaipur Schools of Rajasthan. The use of bright colours, powerful line drawing for illustrating Hindu deities, human and animal representation are closer to the miniature painting tradition which was once profusely executed on paper or cloth.

Pl.12.10: Laila-Majnu story on a rectangular box, Rajasthan. 20th century

Pl.12.11: Octagonal depicting Hindu Gods and other scenes, Rajasthan, 20th century

Pl.12.12: Floral decoration on a rectangular panel, Marwar/Jaipur, Rajasthan, 19th century

Notes and References 'R. Parimoo, Rajasthani, Central Indian, Pahari and Mughal Paintings: (N.C. Meta Collection) Vol I-II (Ahmedabad; 2013); N. Misra, Splendours of Rajasthani Paintings: Gulistan of Alwar School (Delhi:2008); R.Crill, Marwar Paintings (Delhi: 1999); Daljeet, Immortal Miniatures: From the Collection of National Museum (New Delhi: National Museum, 1996); S.N Jai, Splendour of Rajasthani Painting (Delhi: 1991); A. Coomaraswamy, Catalogue of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Part-5: Rajput Painting (Boston: Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1927). 1. Jaitly, Crafts Atlas of India. Delhi; A. Nath and Francis Wacziarg (1987). Arts and Crafts of Rajasthan. (Ahmedabad: 2012). 'Census ofI ndia (1901), 218. 'Author is thankful to Dr. Naval Krishna, former Deputy Director, Bharat Kala Bhavan for sharing this information. 'Author had gathered this information in a personal interview with traditional Rajasthani artists, who were skilled in painting on wood, besides other mediums in December 2012. `In the painted category, colours were applied all over the object. In painting category, on the prepared smooth surface (any medium) painting is done with the help of colour and brush. 'The length of these panels varies from 2.5 to 3ft. and width remains approximately 1 ft. 'Raga poems written in Sanskrit or vernacular languages describe in words the feelings evoked by a raga or musical mode. This group consists of five, six or seven notes arranged in a specific sequence, which expresses a mood (joy, yearning, etc.), and a season and a time of day or night. Each Ragamala usually consisted of thirty-six or forty-two leaves and was organized in a system of families where each family was headed by male (raga), who had several wives (raginis) and sometimes sons (ragaputra) and or daughters (ragaputris) Daljeet, V.K. Mathur and R. Shah, Fragrance of Colours (New Delhi: National Museum, 2003), 3-4. "Author is thankful to Dr. Daljeet, former curator (Painting), National Museum, New Delhi for help and guidance in identifying the ragas and raginis. 20. Diamond, Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur (USA: 2008), p1-20. Ibid.,p1-39 J.M. Dye, The Arts of India: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (USA: 2001), 292-97. A similar style of an enthroned painted Ganesha with his vahana (vehicle) is housed in the personal collection of the Maharaja of Bikaner. This painting is attributed to the artist Hashim. Jaipur School at Bikaner, late 18th century. Gouache and tooled gold on wasli, 17.7 x 12.8cm.<www.Indianminiaturepainting.co.u1c/Bikaner_Ganesha_Hashim_16410.html> "Diamond, 31. First published in Rajasthani Miniature Painting- Tradition and Continuity, National Museum Institute|

The Sarprakshak Training Program was organized in Pune and Ahmedabad by Craft Revival Trust in association with Jeevika. The aim of the workshop was to train the snake charmers as snake educators. The snake charmers were taken to the Zoo in Ahmedabad, exposed to lecture-demonstrations at the Pune Snake Park. They interacted with forest officers to educate them about wildlife laws. This was crucial as there is a ban on the snake charmers occupation as per the Wildlife Protection Act. The focus of the Sarprakshak project is to use the traditional knowledge of the snake charmers for conservation. Over 30 lectures were organized by the country’s leading snake experts and 21 snake charmers traveled from Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi to attend the workshop. The piece below is by Raju Paswan, Community Coordinator, Sarprakshak Project. He has been working closely with the snake charmers and shares some of his experiences here. Prior to this workshop, whenever the name of the Jogi Nath snake charmers was mentioned the popular image of men with snakes draped around their necks, arms and in cane baskets in their bags would arise in my minds eye. My vision would blur with the image of thousands of snakes. Upon encountering and working with the snake charmers I came to realize that there was nothing to fear from them, that they were men just like me, earning a living, keeping alive their traditional livelihood. During the workshop my association with the snake charmers grew to a level where they showed their acceptance of me by referring to me as ‘Raju Nath’, awarding me the status of an honorary member of their community, a sign of their friendship and respect. 21 snake charmers (sapehras) between the ages of 25 and 60 participated in the workshop. They were actively involved in the various sessions, carefully listening to the information being provided them and actively responding with their own views and opinions. The sapehras were a well of information about their community and entertained us with oral narratives which are part of their culture. Though the snake charmers are commonly known for their acts with the snake, I was mesmerized by the skill of the sapehras with the been (bamboo flute used by the snake charmers) whose rhythm and beat had everyone swaying to the tune. They are also skilled in treating snake bites and have an immense knowledge of the medicinal properties of herbs and plants. The organizers learnt that the charmers were initially reluctant to come to the workshop and they feared legal action might be taken against them (Note: snakes are declared endangered species and under the Wildlife Protection Act, anyone caught with a snake can be prosecuted). But they were put at ease as the workshop addressed these issues and alleviated their fears. It was explained that the workshop was to help them to adapt their skills for a more viable employment opportunity while protecting their traditional knowledge. During the workshop the sapehras were asked to work in groups to make suggestions and responses to the topics in discussion. I found myself facilitating the groups’ productivity, understanding group dynamics and encouraging all members to participate. Rather then passively listening to the lectures the snake charmers were active in suggesting what they may do alternative to catching snakes. One day Roshan Nath (participant) suggested that as keeping and showing snakes is illegal and that the snake charmers are untrained for other work the perhaps the government can provide them with the task of protecting snakes. The sapehras repeatedly mentioned their love and respect for snakes and that their sense of community and identity stems from their work. Beyond my role as coordinator of the workshops I also became their friend, mentor and audience. After the days workshops would be over they would come to me and want to talk about what had been discussed, air their views and ask for clarifications. Though their chatter was constant I was constantly amused and entertained. I found that our endeavor to initiate a dialogue and mutual learning was achieved. |

The Harivansha, Gita Govinda and Vishnu, Bhavata, Bharmavaivart Purana are a few important texts which talk in detail about Krishna’s life and his spiritual teachings. These teaching were propagated through religious teachers, priests and saints in different periods in their own ways. Various stories from Krishna’s life, his lilas (his deeds/performances towards the human being) became the source of inspiration for the artists to carve, or put in paint the life stories on stone, bronze, terracotta, paper or cloth, which became the most effective way to reach the common man. Interestingly, weavers and embroiderers also followed the path of other artisans and they made a number of pichhavais, Odhanis, dusbalas, coverlets, hangings etc. which illustrate various life-scenes of lord Krishna though weaving, printing and embroidery work. Krishna in textiles is usually represented in his famous posture of Venugopal through weaving. Episodes of Krishna’s life were illustrated in Kalamkaries through printing and painted techniques. The maximum depiction of Krishna’s life scene was done through the embroidery work of different regions. The most popular motif often found in textiles is the Rasamandal or Rasa through embroideries in Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat, painting on Nathadwara picchavais, and machine made lave pichhavai. Authors have discussed sculptures, terracottas and paintings at length but Rasa on textiles attracted little attention. Rasa as a subject, as a motif is difficult in weaving, but it is beautifully illustrated on embroidered rumals/coverlets from Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat; it has stylistic variations-painted and lace pichhavais. There are few points in this context, which will be examined here. Before going to the subject of Rasa in textiles in detail, brief explanation of the concept of ‘Rasa’ as discussed in literature is necessary. ‘Rasa’ or ‘circle dance’ of Lord Krishna with gopis (cow herds) on the Autumn Moon is one of the most passionate lilas of Bhagwan Shri Krishna, Which is full of life, yet close to God. The most appropriate meaning of Rasa is that the ‘gopis’ are individual souls (jivatmas) and ‘he’ is the supreme soul. (Paramatma) their love is the longing of the individual for the divine. All impediments must be removed before the union takes place. Artistic composition of such a highly philosophical subject is well conceived and transcribed by the Indian artists as reflected in various art forms. Artists had portrayed the subject as beautifully as narrated in literature. The usual depiction of Rasa as it appeared in different mediums is that of Krishna dancing, with the gopis in circle around the seated or standing image of Krishna who is sometimes with Radha. Musicians, drummers, plants, trees, birds, moon etc. are often portrayed around the Rasa to give the ambience of forest. The whole composition is done within a square frame, which adds to the beauty and the artistic sense of the artist.

Any motif, when it starts from the temple (our temples have the credit of introducing most of the art motifs) and reaches the common man makes evident the real achievement of the artist. Almost a similar thing happens with the Rasa motif. Starting with stone sculptures it reached the hands of the women of Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat who expressed it in the form of delicate embroidered coverlets which makes clear the popularity of the subject. As Rasa motif is often found in embroideries, and embroidery is considered to be a folk art so it is a real achievement of the artist that he had made the complex motif in such an easy way that it communicated even the spiritual meaning effectively. Carving of the Rasa motif in relief, on the plain surface of stone and terracotta, or making the colourful painting on paper is easy in comparison to weaving. First we will consider Rasa as it appeared on different textiles. The embroiderers of Himachal Pradesh generally exploit this motif by doing embroidery on rumal, better known as ‘Chamb rumal’. Apart from Chamba rumal this motif is quite often found on ‘Chaklas’, embroidered coverlets, of Gujarat. Two types of pichhavais are also found with the similar motif, one is painted pichhavai and the other is, the machine made lace pichhavai. Before the study of numerous Rasas on Chamba rumal, let us consider the Chamba rumals of Himachal Pradesh.

The most picturesque and colorful embroidery was done on Chamba rumals of Himachal Pradesh, which gained popularity around 18th -19th century. The best-known rumals are from Chamba,

probably they were made at Chamba and hence it got the name of Chamba rumal. Usually these rumals are embroidered on white hand spun muslin cloth (the use of coloured rumals is also attested, National Museum has red coloured muslin Chamba rumal) with colorful floss silk of untwisted threads. Double satin and chain stitches are the main stitches used for embroidering these rumals which give the effect of do-rukha or double sided. Sometimes it becomes difficult to identify the reverse side of the rumal, which is its beauty. These rumals were made for covering the gifts offered to bridegroom from bride’s side or vice versa at the time of marriage, or as cover to the offering made to God. ‘Folk’ and ‘Classical’ are the two types of Chamba rumals, which were found simultaneously during the 18th 19th centuries. As far as the patterns and motif are concerned. Depiction of the Rasa motif is most popular, other motifs are inspired by Krishna’s life-scenes, Siva, Rama, Hanuman, Hunting, Nayika-bheda and geometric designs.

The National Museum has several Chamba rumals in its collection, which depict the Rasa theme both in folk and classical style. Both types of rumals beautifully illustrate the Rasa motif in their own way. It is very difficult to draw a line between the folk and classical style, still, by placing together and studying them thoroughly it can be said that there is a drastic contrast between them. In comparison to the classical style, the folk style of rumals often show the poor lines drawn in bright colours, even the embroidery work (stitches) is done in a very rough manner. After studying the folk style of Chamba rumals, few observations can be made about them.

Mostly, the folk style Chamba rumals (which are in larger numbers in comparison to classical ones) depict four or five pairs of Krishna and gopis, in dancing posture. These figures do not give the clear facial features; the human figures are done in folkish style. In some of the rumals it becomes very difficult to identify the figures of Krishna and gopis. Generally, Krishna is embroidered in the centre, but sometimes, the floral motif is also done in the centre. Most of these rumals are done on coarse cotton cloth embroidered with bright colour silken threads. The National Museum has several such rumals. One such rumal depicts four pairs of Krishna and gopis dancing around the Vishnu figure (PI. 1). Here the artist had made both the figures in similar fashion; both wear long tunic type langha, choli and patka. The blue colour of the face and crown indentify Krishna. The Gopis and Krishna are dancing, holding a flower in hand. The usual floral creeper borders is done in colourful manner. Depiction of animals and birds are around the Rasa and side borders. Double satin and cross-stitches are used for embroidering the patterns, while edges are worked in buttonhole stitches. Cotton cloth has been used for embroidery and interestingly there is a triangular seal, which reads, “FINLAY CAMBELL & Co. MANCHESTER” On the basis of line work, done in folk style, the embroidery work, and the use of bright colours, this rumal can be dated to the first quarter of the 20th century.

Some of the rumals are worked in the folk style but done in a relatively better way from artistic point of view. The National Museum has one such rumal which depicts four pairs of dancing couples around a seated Vishnu image within a circle (PI. 2) on the muslin cloth. Treatment of dancers and their facial appearance indicate that it was done in folk style, but the balance of colours and the beautiful costumes make it a rather good quality work. The pattern is embroidered with double satin stitch, which is of a good quality when compared to the earlier one. Cross and buttonhole stitches are also used –all this appears to be of the last quarter of the 19th century. So in folk style also rumals are done in the beautiful manner.

Any motif, when it starts from the temple (our temples have the credit of introducing most of the art motifs) and reaches the common man makes evident the real achievement of the artist. Almost a similar thing happens with the Rasa motif. Starting with stone sculptures it reached the hands of the women of Himachal Pradesh and Gujarat who expressed it in the form of delicate embroidered coverlets which makes clear the popularity of the subject. As Rasa motif is often found in embroideries, and embroidery is considered to be a folk art so it is a real achievement of the artist that he had made the complex motif in such an easy way that it communicated even the spiritual meaning effectively. Carving of the Rasa motif in relief, on the plain surface of stone and terracotta, or making the colourful painting on paper is easy in comparison to weaving. First we will consider Rasa as it appeared on different textiles. The embroiderers of Himachal Pradesh generally exploit this motif by doing embroidery on rumal, better known as ‘Chamb rumal’. Apart from Chamba rumal this motif is quite often found on ‘Chaklas’, embroidered coverlets, of Gujarat. Two types of pichhavais are also found with the similar motif, one is painted pichhavai and the other is, the machine made lace pichhavai. Before the study of numerous Rasas on Chamba rumal, let us consider the Chamba rumals of Himachal Pradesh.

The most picturesque and colorful embroidery was done on Chamba rumals of Himachal Pradesh, which gained popularity around 18th -19th century. The best-known rumals are from Chamba,

probably they were made at Chamba and hence it got the name of Chamba rumal. Usually these rumals are embroidered on white hand spun muslin cloth (the use of coloured rumals is also attested, National Museum has red coloured muslin Chamba rumal) with colorful floss silk of untwisted threads. Double satin and chain stitches are the main stitches used for embroidering these rumals which give the effect of do-rukha or double sided. Sometimes it becomes difficult to identify the reverse side of the rumal, which is its beauty. These rumals were made for covering the gifts offered to bridegroom from bride’s side or vice versa at the time of marriage, or as cover to the offering made to God. ‘Folk’ and ‘Classical’ are the two types of Chamba rumals, which were found simultaneously during the 18th 19th centuries. As far as the patterns and motif are concerned. Depiction of the Rasa motif is most popular, other motifs are inspired by Krishna’s life-scenes, Siva, Rama, Hanuman, Hunting, Nayika-bheda and geometric designs.

The National Museum has several Chamba rumals in its collection, which depict the Rasa theme both in folk and classical style. Both types of rumals beautifully illustrate the Rasa motif in their own way. It is very difficult to draw a line between the folk and classical style, still, by placing together and studying them thoroughly it can be said that there is a drastic contrast between them. In comparison to the classical style, the folk style of rumals often show the poor lines drawn in bright colours, even the embroidery work (stitches) is done in a very rough manner. After studying the folk style of Chamba rumals, few observations can be made about them.

Mostly, the folk style Chamba rumals (which are in larger numbers in comparison to classical ones) depict four or five pairs of Krishna and gopis, in dancing posture. These figures do not give the clear facial features; the human figures are done in folkish style. In some of the rumals it becomes very difficult to identify the figures of Krishna and gopis. Generally, Krishna is embroidered in the centre, but sometimes, the floral motif is also done in the centre. Most of these rumals are done on coarse cotton cloth embroidered with bright colour silken threads. The National Museum has several such rumals. One such rumal depicts four pairs of Krishna and gopis dancing around the Vishnu figure (PI. 1). Here the artist had made both the figures in similar fashion; both wear long tunic type langha, choli and patka. The blue colour of the face and crown indentify Krishna. The Gopis and Krishna are dancing, holding a flower in hand. The usual floral creeper borders is done in colourful manner. Depiction of animals and birds are around the Rasa and side borders. Double satin and cross-stitches are used for embroidering the patterns, while edges are worked in buttonhole stitches. Cotton cloth has been used for embroidery and interestingly there is a triangular seal, which reads, “FINLAY CAMBELL & Co. MANCHESTER” On the basis of line work, done in folk style, the embroidery work, and the use of bright colours, this rumal can be dated to the first quarter of the 20th century.

Some of the rumals are worked in the folk style but done in a relatively better way from artistic point of view. The National Museum has one such rumal which depicts four pairs of dancing couples around a seated Vishnu image within a circle (PI. 2) on the muslin cloth. Treatment of dancers and their facial appearance indicate that it was done in folk style, but the balance of colours and the beautiful costumes make it a rather good quality work. The pattern is embroidered with double satin stitch, which is of a good quality when compared to the earlier one. Cross and buttonhole stitches are also used –all this appears to be of the last quarter of the 19th century. So in folk style also rumals are done in the beautiful manner. The second group of Rasa on Chamba rumals is of the ‘classical’ style, done in the most beautiful manner with good line work, soft subdued colours and good embroidery work. After studying the classical Chamba rumals depicting the Rasa subject a few observations may be made regarding its stylistic variation in regard to composition, movement and number of figures, colours, stitches, etc. These variations appeared because these were made in different periods and regions of Himachal Pradesh. The most common features in these rumals

is that the artists of Chamba rumals have generally used blue colour for the depiction of Krishna (same as n paintings), Kesariya (yellowish orange) for depiction of Krishna’s dhoti. Gopi are portrayed in a colourful manner, usually in langha. Choli and odhani. Apart from similarity, some variations are also there.

The second group of Rasa on Chamba rumals is of the ‘classical’ style, done in the most beautiful manner with good line work, soft subdued colours and good embroidery work. After studying the classical Chamba rumals depicting the Rasa subject a few observations may be made regarding its stylistic variation in regard to composition, movement and number of figures, colours, stitches, etc. These variations appeared because these were made in different periods and regions of Himachal Pradesh. The most common features in these rumals

is that the artists of Chamba rumals have generally used blue colour for the depiction of Krishna (same as n paintings), Kesariya (yellowish orange) for depiction of Krishna’s dhoti. Gopi are portrayed in a colourful manner, usually in langha. Choli and odhani. Apart from similarity, some variations are also there. First is the central figure in the rumals. Usually Krishna is depicted either scated or standing on a lotus in the innermost circle, sometimes we get Radha also along with Krishna. Apart from Krishna the lotus is also found in the innermost circle in some of the rumals. So it can be said that the depiction of lotus is the symbolic representation of Krishna. Besides these, there is an interesting Chamba rumal in the collection of the National Museum that represents the sun symbol in the innermost circle (PI. 3). This rumal depicts five pairs of Krishna gopis dancing around the sun. The large circular sun having flames all around is depicted with eyes, hair, mouth and moustache. All the dancers are in motion and interestingly they are holding sticks and playing with it in a fashion similar to the Guarati community’s ‘Dandiya Dance’ during the Navaratri Festival. The broad border illustrates the heavily embroidered floral creeper designs and are worked in bright colours. Use of bright colours, style of gopi’s costumes ornamention, jewellery and

the use of double satin stitch (not with fineness) give the impression of its late workmanship, around first quarter of the 20th century.

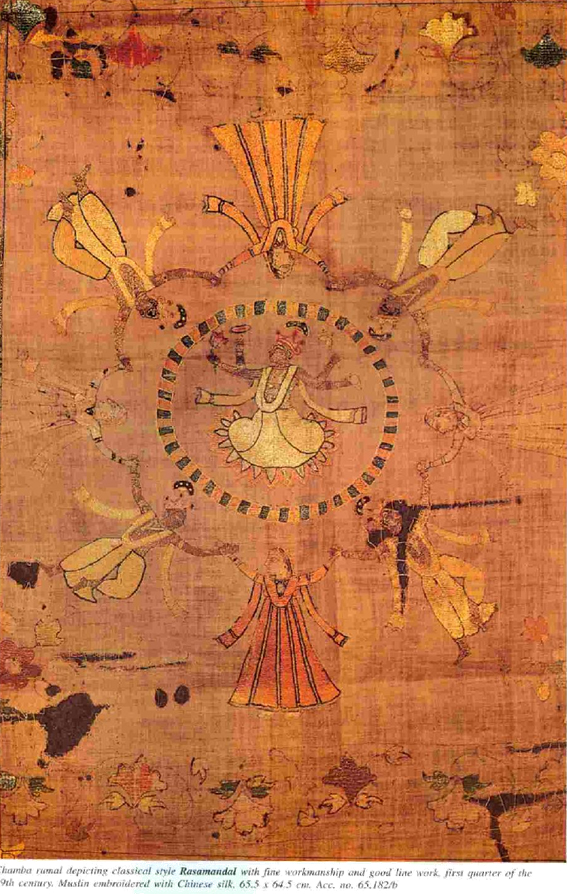

The next important aspect that appears in the classical Chamba rumals is the number of dancing couples in the circle. Four pairs of dancers is the minimum number and the maximum is eight pairs. Quire often five, six and seven pairs of Krishna and gopis are found in these rumals. Early rumals generally depict four or five pairs of dancers and slowly and gradually it increase up to eight pairs. The National Museum has a very early rumal which depicts four pairs of dancers; all are holding each others hands while dancing (PI. 4). These are embroidered on fine muslin cloth in fine double satin stitch with Chinese threads. Extremely fine line work and use of soft subdued colours for dancer’s costumes suggest its date to first quarter of nineteenth century.

In the number of dancers there is one rare and most important rumal in the National Museum collection (PI. 5). In this extremely rare Chamba rumal depiction of double circles of dancers around the seated Krishna and Radha figure, is noteworthy. Interestingly enough, seated Radha-Krishna is shown in the square frame instead of circular frame. In this rumal Krishna is dancing with gopis who had formed the two circles. This type of narration can be seen in some miniature/pichhavai paintings of Rajasthan. Loard Siva, Ganesha and Brahma are witnessing the dance of Krishna. Musicians, trees and peacocks are worked all around. Although the line work and style of embroidery are not of good quality and appear to be in folk style, still this type of double circle dance is rarely seen on textiles. It is an important work of art. The subject, narrative style, subdued coloured silk thread and stitches indicate its date around second quarter of the 19th century.

First is the central figure in the rumals. Usually Krishna is depicted either scated or standing on a lotus in the innermost circle, sometimes we get Radha also along with Krishna. Apart from Krishna the lotus is also found in the innermost circle in some of the rumals. So it can be said that the depiction of lotus is the symbolic representation of Krishna. Besides these, there is an interesting Chamba rumal in the collection of the National Museum that represents the sun symbol in the innermost circle (PI. 3). This rumal depicts five pairs of Krishna gopis dancing around the sun. The large circular sun having flames all around is depicted with eyes, hair, mouth and moustache. All the dancers are in motion and interestingly they are holding sticks and playing with it in a fashion similar to the Guarati community’s ‘Dandiya Dance’ during the Navaratri Festival. The broad border illustrates the heavily embroidered floral creeper designs and are worked in bright colours. Use of bright colours, style of gopi’s costumes ornamention, jewellery and

the use of double satin stitch (not with fineness) give the impression of its late workmanship, around first quarter of the 20th century.

The next important aspect that appears in the classical Chamba rumals is the number of dancing couples in the circle. Four pairs of dancers is the minimum number and the maximum is eight pairs. Quire often five, six and seven pairs of Krishna and gopis are found in these rumals. Early rumals generally depict four or five pairs of dancers and slowly and gradually it increase up to eight pairs. The National Museum has a very early rumal which depicts four pairs of dancers; all are holding each others hands while dancing (PI. 4). These are embroidered on fine muslin cloth in fine double satin stitch with Chinese threads. Extremely fine line work and use of soft subdued colours for dancer’s costumes suggest its date to first quarter of nineteenth century.

In the number of dancers there is one rare and most important rumal in the National Museum collection (PI. 5). In this extremely rare Chamba rumal depiction of double circles of dancers around the seated Krishna and Radha figure, is noteworthy. Interestingly enough, seated Radha-Krishna is shown in the square frame instead of circular frame. In this rumal Krishna is dancing with gopis who had formed the two circles. This type of narration can be seen in some miniature/pichhavai paintings of Rajasthan. Loard Siva, Ganesha and Brahma are witnessing the dance of Krishna. Musicians, trees and peacocks are worked all around. Although the line work and style of embroidery are not of good quality and appear to be in folk style, still this type of double circle dance is rarely seen on textiles. It is an important work of art. The subject, narrative style, subdued coloured silk thread and stitches indicate its date around second quarter of the 19th century. The third point is the dancing posture of the dancers. In most of the rumals the dancers are depicted in two different postures while dancing. In the first style the dancers are shown dancing and facing each other, while in the second style these dancers do not face each other, they are depicted dancing behind each other. Another observation is that in some of the rumals dancers are depicted facing the inner most circle and in some rumals they faced the outer side. Next is the dancing movement of the dancers in the rumals.

Usually, the steps of dancers are shown in movement, in rhythm, as if they are dancing on the fast music with full involvement. In a few early rumals dancers are shown in static form without any movement, as if they are dancing at one place only. It reminds the prevalent dance style of Himachal region where the movement of dancers is slow in comparison to Punjab areas, where the movement of dance is very fast.

As noted earlier, the folk style rumals do not care for line work and therefore fee hand work can be seen. On the other hand, most of the classical Chamba rumals are done with extremely fine line work, which indicates that this kind of work is definitely done by the experienced and trained artists. By examining the line drawing, composition, subject, embroidery work and the colours it has been found that there is a close affinity between the classical Chamba rumals and miniature paintings of this region. The use of soft and subdued colours, well balanced colour contrast and the subject composition all point towards the workmanship of professional artists who were actively working in the courts of Himachal Pradesh. By now most of the scholars have accepted that Pahari miniature artists had done the line drawing of classical Chamba rumals.

in this context there is an interesting point to be noted regarding the subject of Rasa. This Rasa motif is not found in Pahari miniature paintings as prominently as in the numerous Chamba rumals. The reason could be that the Pahari miniature artists who were working for the court of Himachal Pradesh probably were not free to work accordingly to their own choice. Artists had to follow the instructions of their masters; usually they were supposed to paint the rulers or the court activities or whatever their masters asked them to paint. And while making the rumals these artists were free to depict the subject of their own choice, which means that the subject of Rasa was close to a Pahari miniature artist, and that is why this subject is found so often in Chamba rumals.

The third point is the dancing posture of the dancers. In most of the rumals the dancers are depicted in two different postures while dancing. In the first style the dancers are shown dancing and facing each other, while in the second style these dancers do not face each other, they are depicted dancing behind each other. Another observation is that in some of the rumals dancers are depicted facing the inner most circle and in some rumals they faced the outer side. Next is the dancing movement of the dancers in the rumals.

Usually, the steps of dancers are shown in movement, in rhythm, as if they are dancing on the fast music with full involvement. In a few early rumals dancers are shown in static form without any movement, as if they are dancing at one place only. It reminds the prevalent dance style of Himachal region where the movement of dancers is slow in comparison to Punjab areas, where the movement of dance is very fast.

As noted earlier, the folk style rumals do not care for line work and therefore fee hand work can be seen. On the other hand, most of the classical Chamba rumals are done with extremely fine line work, which indicates that this kind of work is definitely done by the experienced and trained artists. By examining the line drawing, composition, subject, embroidery work and the colours it has been found that there is a close affinity between the classical Chamba rumals and miniature paintings of this region. The use of soft and subdued colours, well balanced colour contrast and the subject composition all point towards the workmanship of professional artists who were actively working in the courts of Himachal Pradesh. By now most of the scholars have accepted that Pahari miniature artists had done the line drawing of classical Chamba rumals.

in this context there is an interesting point to be noted regarding the subject of Rasa. This Rasa motif is not found in Pahari miniature paintings as prominently as in the numerous Chamba rumals. The reason could be that the Pahari miniature artists who were working for the court of Himachal Pradesh probably were not free to work accordingly to their own choice. Artists had to follow the instructions of their masters; usually they were supposed to paint the rulers or the court activities or whatever their masters asked them to paint. And while making the rumals these artists were free to depict the subject of their own choice, which means that the subject of Rasa was close to a Pahari miniature artist, and that is why this subject is found so often in Chamba rumals. Apart from Chamba rumals, one more kind of embroidery, ‘Chakla’ of Gujarat, also illustrates the Rasa motif. ‘Chakla’ is the term used for square embroidered rumals, made of either cotton or satin silk base cloth and embroidered with silken threads.

These Chakla were popular among the kati communities in Katihawad region of Gujarat in and around 8th-19th centuries. The Indian tradition of re-cycling things helps not to waste things, but indirectly it is a loss of old traditional things, especially in the field of handicrafts and handlooms, therefore early textile pieces cannot be found. Chakla is one such example, which was used for wrapping the gifts of bride often given to the bride by her mother. Later on these were used as hangings to decorate the bride’s new house or often converted into covers and stuffed with cotton. Usually, the Chaklas were embroidered with elongated darn stitches and a type of feather stitch. Later on, around the 20th century, mochi craftsmanship was introduced and Chaklas were made in the chain stitch also. Generally, mochi embroiderers were engaged in the service of Kathi nobility of the period. They were employed mainly for preparing the embroidered articles for the dowry of the Kathi brides. The ground cloth of Chakla is generally of cotton or silk in indigo, red, orange, yellow or green colour. For embroidery, the artists always used the silk threads and the bright colours like red, yellow, green, maroon, white and black. These Chakla usually depict vividly subjects or motifs such as geometric patterns, flora-fauna and the Rasa.

The National Museum has a beautiful Chakla that depicts the Rasa motif in the most colourful manner (PI. 6). Four pairs of dancing Krishna and gopis around the central figure of standing Krishna and Radha, is shown in the circle. All the four pairs are facing each other very passionately and with full involvement. Dancers are in full movement and they are holding, the stick in their hands. Around the Rasa there is the circular floral border and corners of the Chakla depict wrestling, a pair of peacock, parrot and monkey are on the other side. The Chakla is beautifully embroidered with close herringbone stitch and outlined with chain stitch on the yellow satin silk background, which has a purple border. This border depicts the floral creeper pattern in a colourful manner. An additional zari border is attached to the purple border which indicates that this Chakla may have been used for hanging after being used for wrapping gift. Its date appears to be around the first quarter of the 20th century.

Apart from Chamba rumals, one more kind of embroidery, ‘Chakla’ of Gujarat, also illustrates the Rasa motif. ‘Chakla’ is the term used for square embroidered rumals, made of either cotton or satin silk base cloth and embroidered with silken threads.

These Chakla were popular among the kati communities in Katihawad region of Gujarat in and around 8th-19th centuries. The Indian tradition of re-cycling things helps not to waste things, but indirectly it is a loss of old traditional things, especially in the field of handicrafts and handlooms, therefore early textile pieces cannot be found. Chakla is one such example, which was used for wrapping the gifts of bride often given to the bride by her mother. Later on these were used as hangings to decorate the bride’s new house or often converted into covers and stuffed with cotton. Usually, the Chaklas were embroidered with elongated darn stitches and a type of feather stitch. Later on, around the 20th century, mochi craftsmanship was introduced and Chaklas were made in the chain stitch also. Generally, mochi embroiderers were engaged in the service of Kathi nobility of the period. They were employed mainly for preparing the embroidered articles for the dowry of the Kathi brides. The ground cloth of Chakla is generally of cotton or silk in indigo, red, orange, yellow or green colour. For embroidery, the artists always used the silk threads and the bright colours like red, yellow, green, maroon, white and black. These Chakla usually depict vividly subjects or motifs such as geometric patterns, flora-fauna and the Rasa.

The National Museum has a beautiful Chakla that depicts the Rasa motif in the most colourful manner (PI. 6). Four pairs of dancing Krishna and gopis around the central figure of standing Krishna and Radha, is shown in the circle. All the four pairs are facing each other very passionately and with full involvement. Dancers are in full movement and they are holding, the stick in their hands. Around the Rasa there is the circular floral border and corners of the Chakla depict wrestling, a pair of peacock, parrot and monkey are on the other side. The Chakla is beautifully embroidered with close herringbone stitch and outlined with chain stitch on the yellow satin silk background, which has a purple border. This border depicts the floral creeper pattern in a colourful manner. An additional zari border is attached to the purple border which indicates that this Chakla may have been used for hanging after being used for wrapping gift. Its date appears to be around the first quarter of the 20th century. It will be interesting to compare the Rasa on both the rumals as these have some similarities and some differences. Before discussing the similarities let us see the differences. The basic difference between the two rumals is the base fabric.

Muslin cloth had been used for embroidering the Chamba rumal while coarse cotton or satin silk has been used for embroidering the Chakla. It may be noted that double satin stitch is generally used in Chamba rumals and mochi stitch is frequently used in Chakla. Colours used for embroidering the Chamba rumals are soft and subdued, while Chaklas were generally of bright colours.

As compared to differences, there are more similarities. The first and the foremost similarity between both the rumals is their utility. Both rumals are for covering gifts during the marriage used. Next is size. The Chamba rumal and the Chakla are quite close to each other. The usual size of the Chamba rumals is 78x77 cm. and the size of Chakla is 79x80 cm. The third point is, that in Chamba rumals the floral creeper border is done to make the square frame that is used as the main pattern for decorating the rumal. This is the case of Chakla also. The subject of both the rumals also has a few motifs common to each other, such as geometric forms, ogee, flora and fauna and Rasa. Now let us look at the Rasa rumals. In both the rumals composition of Rasa subject is done in similar manner. Depicting the four pairs of Krishna and gopis within circular frame, movement of dancers, depiction of Krishna and Radha in the innermost circle in Chakla – all these are worked in the same style as in Chamba rumal. By comparing other things also it appears that there are ore similarities in composition, design and size.

It will not be out of context to mention the discovery of B.N. Goswamy regarding the original homeland of Chamba Miniature artists. Prof. Goswamy is of the opinion that some of the miniature artists of Chamba had come from Saurashtra as mentioned in the “Babis of Pandas” of Haridwar. If this theory is accepted then the reason of similarities in both the rumals is clear. Probably some Gujarati artists, who settled in Chamba, Combined their own traditions with the local traditions to produce the rumals.

Next are the two pichhavais (used as hangings behind the images of gods in the shrine),- the painted pichhavai and lace pichhavai. Painted, embroidered or woven, large (around 121 to 315 cm) pichhavais, were used as hanging at the back of the image. Sometimes these were used to decorate the temple and walls, especially during, the ceremonies, related to Krishna, which were the main features of the vallabhacharya had founded this sect. Usually painted on dark blue or white cotton cloth, these pichhavais were painted with white grey, blue-black, yellow and orange colours with touches of silver and gold dust. These large pichhavais depict vividly Krishna’s life and different festivals related to Krishna. Among a number of festivals (there are 24 main celebrations) depiction of Rasa or Sharda Purnima festival is the most popular one, which usually shows Krishna dancing with gopis in the grove. In some of the Nathadwara style pichhavais the number of gopis is more. There are groups of musicians around the Rasa. In some of the pichhavais, the border is quite broad. This border is divided into several sub-sections, which illustrate the life-scenes of Krishna. Painted Rasa pichhavais were very popular because of their colorfulness and good line drawing work.

It will be interesting to compare the Rasa on both the rumals as these have some similarities and some differences. Before discussing the similarities let us see the differences. The basic difference between the two rumals is the base fabric.

Muslin cloth had been used for embroidering the Chamba rumal while coarse cotton or satin silk has been used for embroidering the Chakla. It may be noted that double satin stitch is generally used in Chamba rumals and mochi stitch is frequently used in Chakla. Colours used for embroidering the Chamba rumals are soft and subdued, while Chaklas were generally of bright colours.

As compared to differences, there are more similarities. The first and the foremost similarity between both the rumals is their utility. Both rumals are for covering gifts during the marriage used. Next is size. The Chamba rumal and the Chakla are quite close to each other. The usual size of the Chamba rumals is 78x77 cm. and the size of Chakla is 79x80 cm. The third point is, that in Chamba rumals the floral creeper border is done to make the square frame that is used as the main pattern for decorating the rumal. This is the case of Chakla also. The subject of both the rumals also has a few motifs common to each other, such as geometric forms, ogee, flora and fauna and Rasa. Now let us look at the Rasa rumals. In both the rumals composition of Rasa subject is done in similar manner. Depicting the four pairs of Krishna and gopis within circular frame, movement of dancers, depiction of Krishna and Radha in the innermost circle in Chakla – all these are worked in the same style as in Chamba rumal. By comparing other things also it appears that there are ore similarities in composition, design and size.

It will not be out of context to mention the discovery of B.N. Goswamy regarding the original homeland of Chamba Miniature artists. Prof. Goswamy is of the opinion that some of the miniature artists of Chamba had come from Saurashtra as mentioned in the “Babis of Pandas” of Haridwar. If this theory is accepted then the reason of similarities in both the rumals is clear. Probably some Gujarati artists, who settled in Chamba, Combined their own traditions with the local traditions to produce the rumals.

Next are the two pichhavais (used as hangings behind the images of gods in the shrine),- the painted pichhavai and lace pichhavai. Painted, embroidered or woven, large (around 121 to 315 cm) pichhavais, were used as hanging at the back of the image. Sometimes these were used to decorate the temple and walls, especially during, the ceremonies, related to Krishna, which were the main features of the vallabhacharya had founded this sect. Usually painted on dark blue or white cotton cloth, these pichhavais were painted with white grey, blue-black, yellow and orange colours with touches of silver and gold dust. These large pichhavais depict vividly Krishna’s life and different festivals related to Krishna. Among a number of festivals (there are 24 main celebrations) depiction of Rasa or Sharda Purnima festival is the most popular one, which usually shows Krishna dancing with gopis in the grove. In some of the Nathadwara style pichhavais the number of gopis is more. There are groups of musicians around the Rasa. In some of the pichhavais, the border is quite broad. This border is divided into several sub-sections, which illustrate the life-scenes of Krishna. Painted Rasa pichhavais were very popular because of their colorfulness and good line drawing work. Second, the lace pichhavais were made in Germany for export purpose. This type of work was very popular in northern Germany in the 18th and 19th centuries. At first designs were made by hand and later on these were woven with machine. These lace pichhavais depict several eposdes of Krishna’s life like, Dana Ekadashi, Nauka Vihar and Rasa. The National Museum has beautifully made cotton lace pichhavai depicting the Rasa (PI. 7). This pchhavai illustrates eight pairs of Krishna and gopis, but here the number of gopis has been increased. Instead of eight gopis with eight Krishnas sixteen gopis are depicted. Two gopis are standing on either side of Krishna, which is the style of Nathadwara painting. Radha and Krishna are dancing in the centre. All the figures are worked in Nathadwara style costumes and crown. Peacock and peahen are dancing while musicians are standing in the corner. The border depicts rows of cows and dancing peacocks. Usually these cotton lace pichhavais are made in white colour and to give a clear view, the artists took the support of dark colour cotton lining. Made by the foreign weavers on the basis of the patterns and compositions, which were supplied by the Indian artists, these pichhavais were very interesting.

Thus the subject of Rasa has been examined and found that the embroidered, painters and lace weavers mostly used this subject. But to articulate and transcribe the Rasa motif through weaving in traditional Indian textiles is very difficult, because weaving has its own language, chemistry and manipulation, which is a long, lengthy and complex process. Execution of a motif from the artist’s mind to a weavers loom is complex path. In brief, the first stage of crating the motif is doing the pattern with line drawing on paper, done by the artist. The second stage is the transformation of the motif form paper to graph, indicating the same colour scheme as depicted in the drawing. In the third stage the graphed motif is converted on gata (hard paper) by punching. Now accordingly this punched gata is tied with Naksha and jala is prepared. Once the jala is prepared the pattern comes out automatically, while weaving on the loom.

Second, the lace pichhavais were made in Germany for export purpose. This type of work was very popular in northern Germany in the 18th and 19th centuries. At first designs were made by hand and later on these were woven with machine. These lace pichhavais depict several eposdes of Krishna’s life like, Dana Ekadashi, Nauka Vihar and Rasa. The National Museum has beautifully made cotton lace pichhavai depicting the Rasa (PI. 7). This pchhavai illustrates eight pairs of Krishna and gopis, but here the number of gopis has been increased. Instead of eight gopis with eight Krishnas sixteen gopis are depicted. Two gopis are standing on either side of Krishna, which is the style of Nathadwara painting. Radha and Krishna are dancing in the centre. All the figures are worked in Nathadwara style costumes and crown. Peacock and peahen are dancing while musicians are standing in the corner. The border depicts rows of cows and dancing peacocks. Usually these cotton lace pichhavais are made in white colour and to give a clear view, the artists took the support of dark colour cotton lining. Made by the foreign weavers on the basis of the patterns and compositions, which were supplied by the Indian artists, these pichhavais were very interesting.

Thus the subject of Rasa has been examined and found that the embroidered, painters and lace weavers mostly used this subject. But to articulate and transcribe the Rasa motif through weaving in traditional Indian textiles is very difficult, because weaving has its own language, chemistry and manipulation, which is a long, lengthy and complex process. Execution of a motif from the artist’s mind to a weavers loom is complex path. In brief, the first stage of crating the motif is doing the pattern with line drawing on paper, done by the artist. The second stage is the transformation of the motif form paper to graph, indicating the same colour scheme as depicted in the drawing. In the third stage the graphed motif is converted on gata (hard paper) by punching. Now accordingly this punched gata is tied with Naksha and jala is prepared. Once the jala is prepared the pattern comes out automatically, while weaving on the loom. Now let us examine the case of Rasa motif in brocade textiles in the background of complexity of weaving, Indian has a tradition of brocade from very early days. The zari brocades that have ome down to us are from the 16th century onwards. As far as the patterns or motifs found on saris and odhani are concerned it is found that Indian weavers had woven the most figurative patterns onn loom. Baluchar of Bengal, Patola of Gujarat, Banaras, Gujarat and Kanchivaram brocade are the few best examples of Indian brocade textiles. These woven fabrics illustrate human figures on train, a number of persons riding on a train, a number of persons riding on a boat, horse rider, Nawab smoking a buqqa, flora and fauna, kalka, jala, buta, buti, etc. in spite of such a figurative depiction none of them ever illustrates the Rasa motif, although the illustration of the medallion in silk and zari weaving does appear in Banaras and Gujarat brocade of early 20th century. Char-bagh type Banaras brocade adhani depicts the beautiful medallion in four colours. These odhanis illustrate the floral creeper designs in between the medallions. Gujarat brocade sari depicts the medallion near the pallu, the end piece of a sari. Generally this medallion depicts the floral creeper, sometimes it depicts row of lions in movement (PI. 8). But they do not illustrate the Rasa motif in Zari brocade weaving. Probably this motif is very complex to weave as a pattern. To make a minimum four to five pairs of human figures in motion, that too within a circular frame and treatment of human figures facing each other is very difficult to create, since the usual practice of making the motif/pattern is one block of motif, which is repeated all over the fabric to create the entire design. And the entire pattern comes all over the fabric for the design. Probably it is difficult to create a pattern that has limitations in carrying out several figures within the circular frame.

Similar to brocade medallions there is one more variety of medallions found in the dye odhani of Saurashtra and Kachchha. Fabrics used for odhani were generally made of satin silk or cotton. Usually the entire Odhani is decorated with figurative designs, floral creepers, parrots, elephants and a medallion in the centre. The medallion generally ill.

Now let us examine the case of Rasa motif in brocade textiles in the background of complexity of weaving, Indian has a tradition of brocade from very early days. The zari brocades that have ome down to us are from the 16th century onwards. As far as the patterns or motifs found on saris and odhani are concerned it is found that Indian weavers had woven the most figurative patterns onn loom. Baluchar of Bengal, Patola of Gujarat, Banaras, Gujarat and Kanchivaram brocade are the few best examples of Indian brocade textiles. These woven fabrics illustrate human figures on train, a number of persons riding on a train, a number of persons riding on a boat, horse rider, Nawab smoking a buqqa, flora and fauna, kalka, jala, buta, buti, etc. in spite of such a figurative depiction none of them ever illustrates the Rasa motif, although the illustration of the medallion in silk and zari weaving does appear in Banaras and Gujarat brocade of early 20th century. Char-bagh type Banaras brocade adhani depicts the beautiful medallion in four colours. These odhanis illustrate the floral creeper designs in between the medallions. Gujarat brocade sari depicts the medallion near the pallu, the end piece of a sari. Generally this medallion depicts the floral creeper, sometimes it depicts row of lions in movement (PI. 8). But they do not illustrate the Rasa motif in Zari brocade weaving. Probably this motif is very complex to weave as a pattern. To make a minimum four to five pairs of human figures in motion, that too within a circular frame and treatment of human figures facing each other is very difficult to create, since the usual practice of making the motif/pattern is one block of motif, which is repeated all over the fabric to create the entire design. And the entire pattern comes all over the fabric for the design. Probably it is difficult to create a pattern that has limitations in carrying out several figures within the circular frame.

Similar to brocade medallions there is one more variety of medallions found in the dye odhani of Saurashtra and Kachchha. Fabrics used for odhani were generally made of satin silk or cotton. Usually the entire Odhani is decorated with figurative designs, floral creepers, parrots, elephants and a medallion in the centre. The medallion generally ill.