JOURNAL ARCHIVE

The Poetics and Politics of Indian Folk and Tribal Art

Issue #005, Summer, 2020 ISSN: 2581- 9410

Humans are cultural species. Culture is not a static thing but a dynamic one which grows and evolves. And there is no single form of it. It is manifested in tangible forms like manuscripts, monuments, paintings, sculptures, idols, textiles, things of everyday life, architectural splendours and so on and also in intangible forms like songs, dance, rituals, traditions, folk stories, legends, riddles, decorations, crafts, traditional knowledge about nature and universe, festivals, fairs etc. The present world is witnessing change in all spheres at an unprecedented pace. The cultural landscape is shifting and changing shape. This move is not limited to only physical shifting but is a move away from traditional way of life, continuity of culture, roots, identity and heritage. India is home to many tribes, communities, spaces and culture which are unique and offer diversity of way of life. Each of these communities are unique and hold together socio-cultural and artistic treasures. These are knowledge pools as everything else gets homogenized by the common yardstick of urbanization, globalization and such forces. Ladakh, known for its distinctive landscape located in northern most part of India is one of the highest inhabited place on earth and one of the most unique landscapes in the world with an equally unique culture. Ladakh is known for its distinctive landscape, its unique people, its harmonious attitude towards religion, its vibrant culture and rich heritage. In 2012 a museological research project work was started in Ladakh by the department of Museology, National Museum Institute under my coordination. The project though started with aim of the documentation of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Ladakh has grown multifold to include documentation of all aspects of tangible, archaeological, ethnographic, intangible cultural heritage. What does cultural terms, ideas and conventions mean for different people who practice culture? People who have never been to a museum? And for people who live a way of life so self-sustaining that in many of the the villages there are no shops or prospect of buying off the shelf for another hundred kilometers? Ladakh is one of the few remaining cultural oasis in India guarding an age old yet evolving way of life. Ladakh Covering an area of 87,000 sq Km and a population of 2.74 Lakh as per 2011 census. Ladakh is one of the most sparsely populated regions of India. Ladakh is not just a place but a culture created, preserved and sustained by its landscape, terrain and people. Ladakh was an ancient trade route and for centuries was traversed by caravans carrying textiles, spices, raw silk, carpets, dyestuffs and narcotics stable. It became to be recognized as the best trade route between Punjab and Central Asia. The place and its people are extensively documented in early text and photographs. In the Post-independence India, the region remained restricted for travel for many decades. In 1991, the Leh-Manali highway was opened to civilian traffic and along with the Srinagar-Leh highway it connected Ladakh to the rest of India. From the first decade of 21st century it has become an increasing popular choice for travel destination for Indians and foreigners alike. Heavy tourist traffic, highways crisscrossing Ladakh and used by a large number of vehicles (military convoys, trucks, private and public buses, and jeeps) during tourist season from June to October has changed the way world viewed Ladakh and how Ladakh now views the world from their home windows. This project has become an opportunity to study the changes and challenges being brought in by modern forces to the culture of region which was frog leaped into a new world. The project has metamorphosed in many sub projects leading to Capacity building and Training programme for the museums personnel and community, Museum goes to village programme, Community lead workshops. Some of the main Intangible Cultural Heritage elements documented in Ladakh are Losar(the Tibetan New year), Stone Carving for Mani Wall, Weaving, traditional doll making, Nuroz, Buddhist chanting and tent making(both weaving and setting up). Documentation itself has now progressed to include the archaeological site, petroglyphs, any monument or historic structure in the vicinity, the architecture of the region and so on. This study and its process itself is an ethnographic or rather ethnological study taking place. The project has resulted in an exhibition, three documentary films, workshops, an international seminar, training & capacity building programme and some more. We are at the cusp of setting up two community museums in two nomadic villages in Ladakh, Gya and Kargyam. It is interesting for these self-sustaining villages, their own long standing and evolving traditions, cultural beliefs, oral history, rituals, festivals and way of life has become a catalyst for the community to grasp and approach the issue of protection, documentation and representation of Heritage.|

Our guest column this month is from a rather unusual quarter. If we think of craft as skill and dance also as perfection of skill and both steeped in traditional knowledge systems Ashwini is rather concerned with the resistance amongst many practitioners and also consumers of dance to any form of change or experimentation and also the rather disturbing form of commercialisation being adopted for the knowledge to survive. Craft too suffers from this. Ashwini has written a personal piece for our July issue exploring these murky depths. Sometimes after dancing I ask myself: how do I see my training in dance? Am I merely re-producing what has been taught to me? Am I able to internalise what my hands and legs do? I am yet to find answers to these questions - it has been a process of searching. The dance schools would not want you to ask these questions. Most of the dancers would want to believe that Bharatanatyam is 'divine' and 'sacred', a form danced by lord Shiva and witnessed by Bharata, Nandi and other gods and hence cannot be and should not be questioned or changed by mortals like us. Just as our education system discourages us to ask questions, the dance education coaxes you to live in an illusion that 'traditional' can not be changed. As a student, few incidents made me re-think about what I was doing. I was learning padams, composed by Kshetrayya (a 11th C Telugu poet). I happened to read the translations of these padams by A K Ramanujam ('When God Is a Customer'). In one of the padams, the nayika, is angry at her lover that he has spent the previous night with another woman, asks him to leave when he visits her. As the poem progresses, even though they fight, there is a great amount of passion and attraction between the two. The hero (it could be the lover/ god as lover/ or the king who is the patron) intensely involved with the nayika goes to her to untie her blouse trying lustfully to cup her breasts. She on the other hand, even though angry, is willing to be seduced: it's a beautiful love game. I read this most sensuous, erotic poem and wondered what we were doing? We, in our class, following the Kalakshetra style of dance had chopped off the two stanzas out of three. We only talked about the nayika's anger. I asked my teacher and I was told that dance was 'spiritual' and had nothing to do with 'physical love' and it was devadasis who used dance to sell their bodies until Rukmini Devi 'sanitised' dance by bringing back the purity which was lost for a brief period of time in history! Soon after this I was reading Rustom Barucha's book on Chandralekha, where he writes about one of her early works ' angika' which includes a varnam in huseni raga. The nayika in the varnam, the court dancer, is addressing and accusing the king that he has fallen for the 'other' woman. The same varnam performed in Kalakshetra replaces the king's name with that of god, thus making it tame and sanitised, erasing all the possible erotic-sexual love between the two. A formula where shringara is replaced by bhakti, forgetting that shringara itself can be bhakti. A K Ramanujam called the lover-god as the customer in the house of love; Chandralekha carried it a step ahead. She kept the original version intact and also suggested that the lover is a 'male'. He may take on different roles- a lover, husband, the king, the patron, God, audience; but the 'male gaze' is the same. This opened up a new possibility of looking at Bharatanatyam as a form, which can go beyond meaningless boundaries. At this time, a friend who was equally passionate about her dance did her arangetram- the first public performance in the old-gurukula system. (Arangetram has now become a meaningless show to show off one's wealth, photo albums decorating the coffee tables, and ironically becoming the last performance for most of the dancers) I went to see her perform, I went through a strange experience. She was dancing and for the first time it felt as if I was watching a puppet perform; as if her hands and legs didn't belong to her body. I remembered Chandralekha saying, 'our dancers have stopped using their bodies'. These incidents had changed me- made it impossible for me to go back to the class where one could blindly go on dancing. As a student, one had to look into what 'was' dance and what it 'is' now and what it is to dance. Bharatanatyam till the 1930's when it was still called as 'sadir naach' was practiced and preserved by the community of devadasis. With the upper cast Brahmins taking over the dance scene, devadasis were reduced to take on the role of mere craftsmen training these dancers who became the artists/ performers/ ambassadors of the form. The form itself was made to change to suit the changed audience, also to suit the moral policing of the upper class and caste. Dancers were also eager to export Bharatanataym as 'Indian dance' in our capsule package to the west. On the other hand, few dancers felt that in this process of learning, which had become mechanical we have moved away from the body, which is the most basic of all. There was a need to explore creatively within the form or borrow meaningful insight from other creative forms. A modern movement in dance emerged as a critique of the 'idealisation' of the body in classical dance. Dancers tried to explore with other disciplines, with older forms like yoga, kalaripayyatu, chhau, etc. the idea was to concentrate on the totality of body expression. Whatever form one does, there is always a danger of falling into trap- where the body fails to 'speak' but only 'shows off'. As a performer, the dancer owes a serious responsibility to comprehend from the inside, the nature of each physical form they work with. Dance cannot be mere ornamentation or exploitation of the body, an instrument of skill and spectacle. Dance is rather a process of 'transformation' which involves a travel towards deeper interior spaces within oneself through ones work with the form and body. As a student, it is still the beginning. And I try to ask myself - how do I dance; instead of why do I dance. |

It has been such a long journey, and yet a journey that has only just begun. The August Business Meet in Chennai provided an overview of CCI’s first incursion into what should perhaps have been its foundation: what it takes to make the case for sustainable livelihoods through heritage crafts. We can look back on the seminar which CCWB and CCI together organized in the Victoria Memorial in February 2008 as a Council watershed. We had by that realized the scale of ignorance of the contribution artisans make to national wellbeing. Their economic contribution translated into national production and income figures was needed if wellbeing in other terms (social, political, environmental, cultural, spiritual) was to receive acknowledgement. The consequences of ignorance and neglect had become apparent. Like other activists in the sector, CCI and state chapters seemed destined to run between pillar and post begging for support that awareness could have made automatic. Why had such a lacuna come about in a country with the world’s longest tradition of living craft, where craft had been at the centre of its struggle for Freedom, had been incorporated in to national planning once Independence came, which only the other day was tom-toming its achievements in ‘craft renaissance’, and where even its President acknowledges handcraft as the largest source of Indian livelihood after agriculture? What could be done to resolve the lacuna? Who would do what needed to be done? How long would it take? The Victoria Memorial may have seemed a strange setting for such reflection. Was it not a symbol of a Raj that had forced the decline in Indian handcrafts so as to encourage British exports of machine-made products, a strategy Gandhiji would later counter through his swadeshi movement? Yet as Gopalkrishna Gandhi reminded us, perhaps our setting was not bizarre. After all, VM was built by Indian artisans. They had brilliantly adapted traditional skills to what was for them a contemporary need of commemorating Her Royal Majesty. It was precisely their capacity of innovation and moving with the times which CCI has endeavored to support and promote since its inception. That 2008 seminar shared our dilemma with participants from several sectors of knowledge and experience. What became clear in Calcutta was that our fears were genuine: there was indeed no reliable data on our sector, little appreciation of the cost of this ignorance to national progress, and no place where the responsibility for change could be clearly assigned. Yet change was needed --- and quickly, to counter a growing prejudice that dismissed craft heritage and activity as a ‘sunset’ industry irrelevant to Shining India. The change agent, it soon become apparent, would have to be CCI. No one else seemed to be around to do the job now. CCI might lack experience in data-gathering and statistical methodologies. It might lack economists on its teams and even contact with research institutions. As a small NGO, it could hardly claim the national reach that a data-gathering task like this requires. Yet first steps were needed, studies would have to begin, pilot demonstrations would have to be made --- not tomorrow, but starting yesterday. For this, CCI would require partnerships entirely new to it: with economists and other disciplines related to statistical analysis and planning. Partnership has been the key feature of the journey since 2008. It has taken us through many weeks and months of investigation, exploration and research, culminating in the “Craft Economics and Impact Study” (CEIS) shared with Council chapters in Chennai in August, and then with 20 partners brought together at the Crafts Museum in New Delhi in September, followed by a first round of discussion with senior experts at the Planning Commission. Along the way we have interacted with researchers, scholars and statisticians --- learning from them, and they in turn learning from CCI about a sector vital to every citizen and yet invisible to most despite its enormous scale and significance. As I write, CCI is preparing for another round of discussions in New Delhi, Raghav Rajagopalan in Chennai (who took courage from his development background to lead the CEIS team) is interacting with new partners representing national planning for skills, Shikha Mukherjee (who has strengthened the CEIS team with her economic reporting and networking skills) in Kolkata has just unearthed a treasure-trove of livelihood data and insights, and Ruchira Ghosh at the Crafts Museum is contributing economics know-how not usually associated with the collections in that marvelous institution. Wisdom has come from many sides, with amazing generosity. Development Commissioners for Handicrafts and Handlooms have given us opportunities to participate in the drafting of the 12th Five Year Plan, enabling us to bring to the table knowledge and concerns generated by the CEIS. Far from suggesting that CCI should leave economics to the experts, Planning Commission economists have appreciated the CEIS as a step that had to be taken to impact a much larger context of national policy and action. For them as with others, the CEIS is all about learning together. Learning together is perhaps the key lesson of these months of effort. Learning the economics of handcrafts is just the beginning of what is needed if India is to walk its decades-old talk about our glorious craft heritage. The work on cold statistics is enlivened by fresh understanding of values and issues that go well beyond numbers. We now have evidence to back past hunches of how ‘organized’ and innovative artisans really are (challenging the labels of ‘unorganized’ and ‘informal’ imposed on them), the resources of creativity and innovation they bring to industry well beyond crafts (machine tools, space applications, watches, industrial design), the huge contribution of women to the sector (as much as 50% in key production processes), the critical importance of craft activity to millions still on the margins of our society (women, minorities, tribal communities and those in remote and sensitive regions), the importance of hand production to environmental sustainability (use of local materials and the huge advantage of low carbon-footprint), the deep commitment of communities (including youth) to their heritage….the list goes on. This is a ‘sector of sectors’. To strengthen it demands bringing together many streams of knowledge and experience. Economics is clearly one of these, and yet only one. The future of Indian handcrafts now demands inter-disciplinary teamwork on a scale we have yet to imagine. CCI is familiar with building teams of artisans, craft activists, designers, marketing managers, administrators and planners. Tomorrow’s teams may include the economists we now know and a range of other expertise: livelihood management, sociology, anthropology, finance, corporate management, human rights, environmental science, media…. From the European Union has come that wonderful phrase “The future is hand-made” --- hand-made in India by a myriad partners holding hands?

Using leather, multi-coloured threads, mirrors and cotton cloth the craftspersons of the Meghwal Community from the Banni and Pachchhan areas of Northern Bhuj create the most astonishingly gay and cheerful leather panels, mirrors, chappals and other decorative and utilitarian items made of leather. Leather work is a striking example of a craft that has successfully moved out of the village milieu into the urban market. The craftspersons fashion products of interest for the larger city markets with accustomed ease. Buying their raw materials locally - leather from Ahmedabad, mirrors from the village itself - they create products that are being marketed and sold internationally.

The products are gay and reasonably priced and sold in towns, on orders, at haats and exported.

The products are gay and reasonably priced and sold in towns, on orders, at haats and exported.

Kohlapuri chappals are handcrafted leather sandals that get their name from the place of their origin, the district of Kohlapur in the state of Maharashtra. Specific dates and details about the origin of this craft are unknown, but the cobblers of this district have succeeded in creating a globally recognised product. These chappals, which were probably worn only by the inhabitants of Kohlapur, are now worn all over India and abroad. They are especially popular among college- going students and tourists, who buy these chappals - which keep their feet cool during the hot summer months of India - at nominal rates.

Each piece, complete with intricate patterns, is handcrafted out of leather; even the cords used to stitch the sandals are made of leather and no nails are used in the production. The chappal is made of buffalo hide while fine goat leather is used for the plaited strips that decorate the upper portion of the chappal. The raw leather which is bought from traders is made pukka or hardened by drying and grazing it. After the grazing is done, the large pieces of leather are cut to the size required by using templates. The leather used is either in its natural tan colour or dyed deep brown or deep black maroon, depending on orders and requirements. The sole, which is the first part of the chappal to be made, is cut and then the two pieces of leather are pasted together and stitched with leather thongs for added strength. Before the edges are hand stitched the two portions of the leather sole are temporarily stuck together with finely grained black clay taken from the rice field. Industrial glue is used only for the sticking of rubber soles. Once the base of the chappal is ready, the main design is created. There are a number of designs that have evolved over time to cater to contemporary demands.

Each piece, complete with intricate patterns, is handcrafted out of leather; even the cords used to stitch the sandals are made of leather and no nails are used in the production. The chappal is made of buffalo hide while fine goat leather is used for the plaited strips that decorate the upper portion of the chappal. The raw leather which is bought from traders is made pukka or hardened by drying and grazing it. After the grazing is done, the large pieces of leather are cut to the size required by using templates. The leather used is either in its natural tan colour or dyed deep brown or deep black maroon, depending on orders and requirements. The sole, which is the first part of the chappal to be made, is cut and then the two pieces of leather are pasted together and stitched with leather thongs for added strength. Before the edges are hand stitched the two portions of the leather sole are temporarily stuck together with finely grained black clay taken from the rice field. Industrial glue is used only for the sticking of rubber soles. Once the base of the chappal is ready, the main design is created. There are a number of designs that have evolved over time to cater to contemporary demands.

P G J Nampoothiri and Gagan Sethi. Books for Change National attention is focused once again on the Gujarat pogrom of 2002. Conflicting accounts have emerged from the Supreme Court’s Special Investigation Team (SIT). Its apparent exoneration of Narinder Modi is challenged by the Courts amicus curiae, while a cover story in TIME on the Chief Minister as India’s icon of economic growth has failed to remove the visa ban imposed by the US since 2002 on grounds of human rights violations. This book recounts Gujarat’s tragedy from the perspective of a special monitoring group set up by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) soon after the killings began, on which the co-authors served. Their conclusion is chilling: “The vibrance of the State ensures that life is a series of celebrations from Kite Festivals to Garbas to Diwali and carnivals. The list is endless. In such a scenario, who wants to remember what happened to some of our own brethren just a few years back?” Reason enough for this riveting reminder of what happened during three terrible months in 2002, and in the ten years that have followed even if two baffling mysteries remain: what actually happened at Godhra station on 27 February 2002, and later the same day in the CM’s Gandhinagar office when instructions were given to assembled officials and police? Gujarat’s failed experiment in ethnic cleansing is traced back by Nampoothiri and Sethi to Gujarat’s age-old contacts with Islam and the impact of ‘divide and rule’ during British colonialism. The violence of Partition was followed by periods of harmony, including the unity of all communities during the Mahagujarat movement. The new states lofty ideals were shaken in 1969 when the Gujarati press “went berserk” in reporting an incident at Ahmedabad’s Jagannath temple, stoking unabated violence just as irresponsible Gujarati media would do again 32 years later. The authors describe 1969 as the “defining movement”, revealing the political possibilities of communal discord that would be exploited first by the RSS, Jan Sangh and Hindu Mahasabha, then by the Congress’ infamous KHAM strategy to regain lost power, by the VHP yatras of the 1980s that led on to the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, and finally to the destruction of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992. As Gujarat was swept into another wave of violence, its path to 2002 was being traced in blood. Losses in bye-elections and signs of Congress resurgence suggested the BJP’s need for what the author’s describe as “something spectacular”. A gory spectacle was offered by the tragedy at Godhara station on 27 February when 59 of kar-sevaks returning from Ayodhaya were killed in the inferno that engulfed Coach No S6. With the CM’s visit, the fateful decision was taken to transport the charred bodies by road to Ahmedabad, overruling the advice of the local Collector. As blood poured from stoked passions, Gujarat turned quickly into flame. Nampoothiri and Sethi were part of a special monitoring group set up by NHRC in soon after the killings began. Both had impeccable credentials in the service of their adopted state: Nampoothiri as a police officer since 1964 and Sethi as the co-founder of Ahmedabad’s renowned Janvikas-Centre for Social Justice. NHRC’s intervention helped the outside world to know correctly what was happening in Gujarat, although the Commission itself faced formidable hurdles to stay its hands. False claims were made that NHRC had denied hearings to petitioners, and that its Chairman Justice J S Verma was hostile to Gujarat because he had been involved as Chief Justice in legal positions on the Narmada Dam! The authors record the violence that was meticulously researched and planned, with mobs “fully prepared” through a “carefully crafted strategy of mass involvement of the public at large”. With few exceptions, Gujarat’s multitude of godmen, entrepreneurs and prominent citizens maintained a strict silence as the pogrom engulfed village after village, city after city in a conspiracy of silence shared by many. Desperate pleas to the police for help from terrified Muslim communities drew a response entirely new to Indian experience “We have no orders to save you”. What happened at a meeting in the CM’s office in Gandhinagar on the evening of 27 February 2002 has remained bitterly controversial ever since. Nampoothiri and Sethi recount the several versions of that event, recording the belief that “there was no discussion. The Chief Minister spoke and the others dutifully listened. No officer has cared to openly share information as to what transpired.....but secretly and in confidence a few have talked...The Chief Minister left no one in any doubt whatsoever on what was expected of them (and what was not). Undoubtedly the instructions were clear and simple....” The gruesome strategy to leave Gujarat’s Muslims homeless and hopeless is recalled in a heartbreaking litany of assault, murder, rape, arson and looting gathered by NHRC investigators. These include the burning of Best Bakery and 14 of those who lived and worked there, the trauma of Zaheera Sheikh who witnessed this slaughter, the heroism of gang-raped Bilkish Bano and her husband Yakub in braving threat to seek justice over ten years of intimidation, the slaughter at Gulburg Society of Congressman Ehsan Jafri and 58 others (calls to high places for help all ignored), the “indescribable bestiality” of the rape and murder of Kausarben and her unborn child, a thousand homes in Naroda torched, “not one shop in a stretch of about two kilometres could be saved”. The list continues, as does “the reluctance of various officials to honestly perform their duties” with “sickening regularity”. Traditional amity between Muslims and dalits and adivasis was broken by years of well-planned strategies for polarisation through “a strong dose of religion”. “Special care was taken to destroy heritage sites”: the monument to musician Ustad Faiz Khan and the Bandukwala library in Baroda decimated, as were 302 dargahs (including that of the medieval poet Wali Gujarati, bulldozered within sight of Ahmedabad’s Police Control Room), and over 200 mosques. Gandhi’s Sabarmati Ashram was targeted, even as his influence seemed to have fled Gujarat. Mayhem was facilitated by successfully dividing Muslims from other marginalised communities, Advisai and Dalit. Electoral roles were used to target Muslim locations with great precision, even in Gandhinagar’s “impenetrably fortified Secretariat”. Even after “inordinate, unpardonable delay in the army deployment” more than twelve hours after they have landed at Ahmedabad, the Army were made “to cool their heels ... waiting for red flags to be provided” while middle-class citizens participated in looting. Worse was to follow. Over 150,000 fled into some 150 relief camps hurriedly organized in mosques and graveyards. Denied State attention and even the most basic relief facilities, forcible closures were spurred by Modi’s description of relief camps as intolerable “children producing factories”. Innuendo was used to imply that the National Commission for Minorities, the Chief Election Commission and Human Rights Commission were all institutions biased toward Muslims. Compensation was denied, then withheld or set at absurdly low levels. Gujarat’s mature experience in Narmada rehabilitation and its 2001 earthquake management was now nowhere to be seen. Attempts to return home were faced with social and economic boycott, demands that none of the accused in neighbourhood criminal cases should be punished, and offers of compensation that were “sometimes less than even Rs100”. With the authorities making “no effort to conceal or disguise discrimination”, the authors devote one of the most perceptive chapters in this important book recounting “the short journey” from relief camps to colonies of 4,500 internally displaced families whose earnings have been crushed by some 75%. That remains today as one of the most tragic legacies of Gujarat 2002. Here and there, as NHRC record show, upright officers did their duty in face of unimaginable odds. Soon the “cynical attempt to capitalise on communal polarisation” would lead to Modi’s surprise recommendation in July to dissolve the Assembly, even in the midst of sporadic violence. In elections finally held in December 2002, the BJP returned to power with a two-thirds majority. The implications of this victory for Gujarat and for India have been debated even since. The book concludes with an analysis of Modi’s recent ‘Sadhabhavana’ extravaganzas: colossal melas at huge public expense, made famous by his refusal of a Muslim headgear, even as relief and compensation are denied to thousands after a decade of waiting. So what about the future? While the book attempts to shake a collective amnesia, the authors conclude with a telling observation. NHRC Chairperson Justice Verma’s letter to the Prime Minister in 2003 regretting that “not enough had been done to ensure the victims, our country and the world at last, that the instruments of the State are proceeding with adequate integrity and diligence to remedy the wrongs that have occurred” has to this day been left unacknowledged.

Issue #10, 2023 ISSN: 2581- 9410

My experiments and interpretation

Indian textile traditions, rich and diverse, today have a special place for linen, a yarn with a history as rich as the culture itself. As a versatile and sustainable yarn, linen has found itself a new definition in modern India's fashion panorama, notably through our disruptive innovation of the linen sari and its ever going popularity amongst the sari lovers.

My journey with linen began many years ago. I started my design carrier as a menswear designer in an Indian corporate firm. That is when I first started working with linen textiles for men’s shirts. My first notes were: Linen whencompared to cotton or silk was thicker, more coarse and it wrinkled. But the very same features made it special, a textile that had a personality of its own and one had to work around it. Difficult to manipulate and control this yarn with its quiet luxury and unique personality soon became my favourite.

I moved into a craft cluster project after 4 years of corporate job. The 3 years I spent on this project opened my eyes to the unique possibilities in the handloom sector and handwoven textiles. I took a sabbatical from active work once my son was born, but those slow and mindful 5 years laid the foundation of all my future work. As I was planning to get back to design and textiles I consciously started looking at the work of various artisans and designers in this area. My strong desire was to create a contemporary, easy and minimalistic sari that was modern yet deeply rooted in our textile tradition.

When I looked at Indian sari in 2009- 2010 from a city context it was surely an epitome of feminine grace and Indian heritage but it did carry a bit of formality with it and was either limited to a festive wardrobe or occasion wear. During the same time there was also an ever-growing chatter about younger generation losing interest in the sari. We saw a rise in the sari support groups and platforms both online and offline. There seemed to be a new found revolution where women wanted to reclaim the sari and re frame their relationship with this beautiful textile.

With this background I asked myself a simple question, what is the sari I would want to wear. It took me days to put my ideal sari into words: a sari that is elegant and minimalistic at the same time, where the texture and the feel does the talking, a canvas that gives the wearer an opportunity to showcase their personality through it and doesn’t define them. And I instantly thought of linen a yarn whose quiet luxury had bewitched me long time back.

Once I decided to work with linen on a handloom in 2010, the next question was which cluster. Being familiar with Banaras and Maheshwari weaving clusters I started speaking to the weavers in these regions. My research on yarn source led me to Jayashree Textiles, a company under the Aditya Birla group of companies that is the leading linen brand in India. It is the biggest integrated linen factory in the nation and has cutting-edge spinning, weaving, and finishing equipment.

After sourcing the yarn I started my experiments in Varanasi and Maheshwar, the weavers here were proficient in handling both silk and cotton in warp and weft. But due to the properties that make linen yarn brittle when dry we were unable to put a linen warp in these clusters and the blend with cotton warp or silk warp was unstable to start with, also with a result not to my liking.

Further study of the yarn and its behaviour made it clear that we needed an environment with moisture to make this yarn work on the handloom, and the weavers in Varanasi gave me a lead to Phulia region in west Bengal.

When I first approached the weavers there, most of them couldn’t come to terms with doing Linen on wide width (sari) and refused. I had already created the linen sari in my mind, I couldn’t take no as an answer. I was persistent. I finally found someone who was willing, Mr Sarkar a seasoned weaver working on linen blended stoles for export market, he told me the difficulty of moving the yarn on a bigger width, when he had problems in making the stoles. Linen breaks easily when dry and can’t take the rigour of the handloom. I requested him to at least try and all the loss would be on me if we fail. He agreed to work on a sari reluctantly and I returned to Singapore where I was living at that time. I would touch base with him every now and then for the progress and he would update me. We had agreed that the sari will be woven with a loose weave and the loom setting would be done in a way that we have a gauzy textile easy to drape and not too heavy. After a few months I got a message from him and received a parcel and as I opened it I saw my dream in front of my eyes. It was the right weight, the natural linen tone, the soft silver selvedge’s as I wanted to stay away from the traditional border and the raw texture of mother nature itself. That moment was one of the most satisfying and happy moments of my career.

Now I had the linen sari, but I wanted to be sure of the product, its features and how it behaved before introducing it. We all know Linen as a yarn is cherished for its comfort, unlike synthetic materials that trap heat, linen allows the skin to breathe, making it an ideal choice for the Indian climate. Linen's natural properties make it resistant to bacterial growth, further enhancing its suitability for tropical and subtropical environments. I started wearing this sari and was amused by the sheer beauty of the drape, the way it followed my contour and allowed me to breath, wrinkled as the day proceeded but looked even more charming. It had a natural lustre, and Its rich texture and the distinctive crumples added a sense of understated elegance to the fabric.

That was the day 13 years ago that decided the course of my design carrier. I called the weaver and congratulated him for the work. Surrounded with tant, silk and jamdani saris he was utterly confused with my excitement on a sack like textile. I soon went to India and planned a small collection of saris with few more designs. I had to give him entire advance for the project as he felt it was a big risk to start making linen saris for which he felt there was no market. We started working on two looms he had. In a matter of 4-6 months we had a small collection of 12 saris. by then I had shifted back to Mumbai. I met Radhi Parekh of Artisans Gallery in Kalaghoda and we planned a show around the Khatwa work I was doing with a few artisans and introduce the linen saris.

The exhibit was a huge success and as they say rest is history. I met my very first clients at that exhibition, they were as excited to see the linen saris as I was to create them, they are now regular linen sari wearers and I am still in touch with them . From the very beginning we have placed linen at the forefront of our textile narrative and we stay true to it till date.

I feel by adopting linen as a primary material, we have in a way given traditional weavers an opportunity to diversify their craft and engage with contemporary fashion narratives. In the last 13 years we have continued to experiment on the loom with this yarn. whether its new textures or the usage of slub yarns, experimenting with tye-dye, zari and silk insertions or contemporary interpretations of jamdani weaving our linen saris are a testament to the versatility of this age-old yarn. They exhibit a harmonious blend of traditional weaving techniques and modern designs. The brand's approach to linen reflects a nuanced understanding of the material's potential, both in terms of comfort and design.

Notably, the linen saris have gained popularity for their elegant minimalism. The lightweight, breathable linen is perfect for daily wear, while the intricate craftsmanship and unique designs make them suitable for more formal occasions.

Beyond saris, we have also experimented with linen in a range of contemporary apparel. We have used handwoven Linen for dresses, tunics, and trousers with our distinct aesthetic that reflects the brand's commitment to sustainable luxury.

In conclusion, linen as a yarn holds a significant position in the Indian textile tradition. Its unique properties have allowed it to flourish in the Indian context, both as a material for traditional crafts and in contemporary fashion narratives. Through innovation, linen continues to evolve while maintaining its intrinsic relationship with sustainable and comfortable living. Linen, it seems, is not just a yarn, but a testament to the artistry of weavers, the vision of designers, and a commitment to sustainability and style. It is also a successful example of collaborative work both in terms of designer and weaver and foreign yarn on Indian Handlooms and just opens our minds to possibilities that await us.

|

Please click on the link to read the article:

|

"...like the tribal sculptors, who praise the 'direct' method of casting (hollow casting) illustrated in this exhibition, it bears also a deeper, more anxious significance for the artist, since in the interval between the drawing off (of the wax) and the pouring in (of the metal) his creation has become void and can be recovered only by a successful pour; a failure means that all his work is lost with the wax (since the clay envelope, and with it its negative impression of the wax, are necessarily broken up), and he must begin again, perhaps never again to recover his original inspiration. We may say, with reason on our side, that the act of creation in lost-wax casting consists in the modeling of wax, yet we need not be surprised if to the tribal sculptor with his traditional philosophy of vital force, and perhaps to the true artist everywhere, the moment of pouring seems like a mystical act of procreation..." From Introduction by William Fagg to a catalogue of an exhibition - Lost Wax Metal Casting on the Guinea Coast. Institute of Contemporary Art, London, March 1957 Lost wax or cire perdue metal casting is practiced in many areas in India, but the folk brasses cast with this method in the Bastar region of middle India contain certain tribal elements that set them apart. Bastar is located in the southern region of Madhya Pradesh where the state borders Andra Pradesh. The craftsmen of this area belong to the Ghadwa or Gharua Scheduled Caste, also known as Kaser, Ghasia, Mangan and Vishwakarama, although most of these names are self-proscribed by the craftsmen in order to raise their social status. The Ghadwa create jewelry, local deities and daily utensils for the villagers of their area. The jewelry items consist of pairy = anklets, aenthi = toe rings, fulli = nose pins and ghungru = decorative bells. Figural images not only include local deities but also extend to votive forms of snakes, horses, ritual pots, as well as other birds and animals used for decorative objects. Although these craftsmen are spread throughout the region, a slightly larger settlement exists in Kondagaun and Jagdalpur where items are created on a small industry scale.

| Ram Wax Model – By Chattisgarh Craftsman, at Crafts Museum, New Delhi, now in private collection, United States |

| Pichki and Pharni, image by author |

| Ganesh Playing a Gong – By Chattisgarh Craftsman, at Crafts Museum, New Delhi, now in private collection, United States |

| Village Woman Wax Model – By Chattisgarh Craftsman, at Crafts Museum, New Delhi, now in private collection, United States |

| Woman prepares a meal while her husband performs Puja – By Chattisgarh Craftsman, at Crafts Museum, New Delhi, now in private collection, United States |

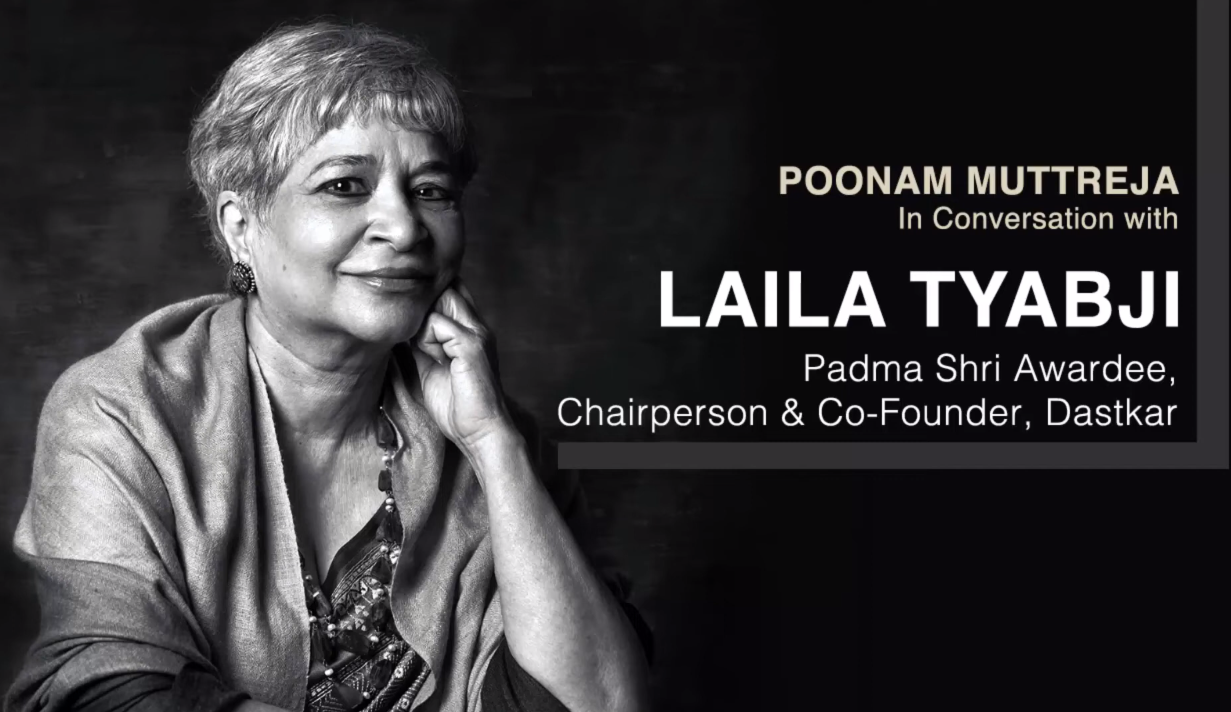

In a culture where people seldom speak their minds to friends, the historian and international textile authority could be a fierce critic when she felt one was going astray. [caption id="attachment_198234" align="alignnone" width="569"]

Lotika Varadarajan. Courtesy: Laila Tyabji[/caption]

Lotika Varadarajan, the historian, international textile authority, inspirational teacher and an intrepid traveller, passed away a few days ago. She was a friend for over three decades; a source of knowledge, support and inspiration, serving too on the board of Dastkar in the 1980s. Even more valuable, in a culture where people seldom speak their minds to friends, she could be a fierce and articulate critic when she felt one was going astray.

I Ioved her passion, her drive and dedication, her mischievous humour. Her esoteric unexpected bits of knowledge about everything from the 17th-century trade routes, which brought my ancestors to India from Yemen, to the flowers that cows were fed to make their urine more yellow (an essential element in the original kalamkari process). Her delight at a new snippet of information or the achievements of a craftsperson. The unforgettable way her rather serious face would suddenly light up with a radiant smile, her luminous brown eyes (always heavily outlined with kohl) glowing with warmth and fun. She loved a joke, and cracked many, often at her own expense or that of her frequently malfunctioning hearing aid.

Her small, neat figure, always in a firmly-wound handloom sari, the pallav tucked in at the waist, will be much missed in craft discussions and forums, her head cocked to hear every last word, her precise, carefully chosen but never minced words, her determination to get to the bottom of everything, regardless of the ticking clock or the place. I was once captured by her in Khan Market and cross-examined for 15 minutes on the provenance of my sari while a road jam of cars blew their horns in increasingly loud disapproval. Varadarajan was impervious, having discovered a variation of Siddipet weaving she was unaware of.

How disappointed she was when someone’s depth of knowledge or curiosity didn’t match her own. Learning of my family’s Arab roots, she was aghast at how little I knew of their voyages to India. “But Laila, you must find out! It’s very important…..” I remember her saying reprovingly. She herself knew the type of ship they must have travelled on, the wood it was made of, the shape of the sails and prow, the seasonal winds that blew them to the sands of Cambay…. Medieval maritime trade was one of the many areas she made her own.

Others included Kalamkari and Ajrakh block printing, Paithani weaving, Indo-Portuguese embroidery, indigo dying, Kerala and Kutch boat building, the ethnography of Karappur royal garments, the Fustat textiles, Konyak tribal traditions, loom technology, the contents of Shivaji’s toshakhana and the calendrical systems of the Nicobar islands. In each case, folk memory was her favoured source material, as vital as the historic documents she tracked down in libraries all over the world.

Her list of publications and papers is mind-boggling, as she travelled from the Northeast to the Andamans, Lakshadweep and Indonesia, to Portugal, Italy and Greece, to the USSR, South America, Southeast Asia and Australia; speaking at conferences, uncovering and sharing data and information, making friends and admirers everywhere. She wore her scholarship and international renown lightly but was never casual about scholarship itself. Nothing made her crosser than superficial generalisations unbacked by research and hard facts. She was a purist too, disliking some of the aberrant directions Indian craft had taken in search of new markets. Her disapproval of “those horrible synthetic black mannequins” we used to display garments at Dastkar exhibitions was a fond joke.

Nevertheless, she was far from the stereotype singleminded strait-laced academic, beginning with her inter-community romance and marriage in England – a Bengali girl marrying a Tamil-Brahmin in the 1950s. At her remembrance service, one of her research students told a lovely story of Varadarajan opening her wine cabinet one evening and discovering its rather meagre contents. “Put on some lipstick and let’s go,” she urged the young researcher, and off they went to a reception at one of the embassies, where they had several glasses each of a more satisfactory vintage.

And when she was invited to spend several months in Europe as a visiting scholar in the 1980s, she landed up in the office with a wonderful old Himachali woollen pattu, demanding I design a stylish coat for her, one that she could wear with her saris. I enjoyed that and so did she.

My favourite memory is when, in the midst of some scholarly get-together at the India International Centre, a long-lost male acquaintance came up and regaled us with rather raunchy anecdotes of their shared university days, (she was at Miranda House and then Cambridge) and how her voluptuous hourglass figure, in a tightly wrapped sari even then, was the cynosure of adolescent masculine eyes. It’s the only time I saw her disconcerted.

As much a part of her as her scholarship was her enormous generosity of spirit. She was always ready to share information, to introduce a researcher to a source, to act as a host and go-between for two people she felt would enjoy meeting one another. In the secretive, often suspicious world of academia this was quite rare. Her home was a haven to family, friends, visiting international scholars, young students. She opened many doors for me, both of knowledge and friendship, over the years. One sentence will always resonate: “To sacrifice craft traditions at the altar of modernity is tantamount to adding yet another dimension to the poverty of the mind.”

Thank you, dear Lotika. Rest in peace. I will miss you.

Lotika Varadarajan. Courtesy: Laila Tyabji[/caption]

Lotika Varadarajan, the historian, international textile authority, inspirational teacher and an intrepid traveller, passed away a few days ago. She was a friend for over three decades; a source of knowledge, support and inspiration, serving too on the board of Dastkar in the 1980s. Even more valuable, in a culture where people seldom speak their minds to friends, she could be a fierce and articulate critic when she felt one was going astray.

I Ioved her passion, her drive and dedication, her mischievous humour. Her esoteric unexpected bits of knowledge about everything from the 17th-century trade routes, which brought my ancestors to India from Yemen, to the flowers that cows were fed to make their urine more yellow (an essential element in the original kalamkari process). Her delight at a new snippet of information or the achievements of a craftsperson. The unforgettable way her rather serious face would suddenly light up with a radiant smile, her luminous brown eyes (always heavily outlined with kohl) glowing with warmth and fun. She loved a joke, and cracked many, often at her own expense or that of her frequently malfunctioning hearing aid.

Her small, neat figure, always in a firmly-wound handloom sari, the pallav tucked in at the waist, will be much missed in craft discussions and forums, her head cocked to hear every last word, her precise, carefully chosen but never minced words, her determination to get to the bottom of everything, regardless of the ticking clock or the place. I was once captured by her in Khan Market and cross-examined for 15 minutes on the provenance of my sari while a road jam of cars blew their horns in increasingly loud disapproval. Varadarajan was impervious, having discovered a variation of Siddipet weaving she was unaware of.

How disappointed she was when someone’s depth of knowledge or curiosity didn’t match her own. Learning of my family’s Arab roots, she was aghast at how little I knew of their voyages to India. “But Laila, you must find out! It’s very important…..” I remember her saying reprovingly. She herself knew the type of ship they must have travelled on, the wood it was made of, the shape of the sails and prow, the seasonal winds that blew them to the sands of Cambay…. Medieval maritime trade was one of the many areas she made her own.

Others included Kalamkari and Ajrakh block printing, Paithani weaving, Indo-Portuguese embroidery, indigo dying, Kerala and Kutch boat building, the ethnography of Karappur royal garments, the Fustat textiles, Konyak tribal traditions, loom technology, the contents of Shivaji’s toshakhana and the calendrical systems of the Nicobar islands. In each case, folk memory was her favoured source material, as vital as the historic documents she tracked down in libraries all over the world.

Her list of publications and papers is mind-boggling, as she travelled from the Northeast to the Andamans, Lakshadweep and Indonesia, to Portugal, Italy and Greece, to the USSR, South America, Southeast Asia and Australia; speaking at conferences, uncovering and sharing data and information, making friends and admirers everywhere. She wore her scholarship and international renown lightly but was never casual about scholarship itself. Nothing made her crosser than superficial generalisations unbacked by research and hard facts. She was a purist too, disliking some of the aberrant directions Indian craft had taken in search of new markets. Her disapproval of “those horrible synthetic black mannequins” we used to display garments at Dastkar exhibitions was a fond joke.

Nevertheless, she was far from the stereotype singleminded strait-laced academic, beginning with her inter-community romance and marriage in England – a Bengali girl marrying a Tamil-Brahmin in the 1950s. At her remembrance service, one of her research students told a lovely story of Varadarajan opening her wine cabinet one evening and discovering its rather meagre contents. “Put on some lipstick and let’s go,” she urged the young researcher, and off they went to a reception at one of the embassies, where they had several glasses each of a more satisfactory vintage.

And when she was invited to spend several months in Europe as a visiting scholar in the 1980s, she landed up in the office with a wonderful old Himachali woollen pattu, demanding I design a stylish coat for her, one that she could wear with her saris. I enjoyed that and so did she.

My favourite memory is when, in the midst of some scholarly get-together at the India International Centre, a long-lost male acquaintance came up and regaled us with rather raunchy anecdotes of their shared university days, (she was at Miranda House and then Cambridge) and how her voluptuous hourglass figure, in a tightly wrapped sari even then, was the cynosure of adolescent masculine eyes. It’s the only time I saw her disconcerted.

As much a part of her as her scholarship was her enormous generosity of spirit. She was always ready to share information, to introduce a researcher to a source, to act as a host and go-between for two people she felt would enjoy meeting one another. In the secretive, often suspicious world of academia this was quite rare. Her home was a haven to family, friends, visiting international scholars, young students. She opened many doors for me, both of knowledge and friendship, over the years. One sentence will always resonate: “To sacrifice craft traditions at the altar of modernity is tantamount to adding yet another dimension to the poverty of the mind.”

Thank you, dear Lotika. Rest in peace. I will miss you.