JOURNAL ARCHIVE

Jade is a rare variety of mineral rock, admired and used for creating exquisite items of multifarious utility in different parts of the world from time immemorial. Its inherent qualities such as hardness yet not appearing so, translucent glossy surface almost to a point of luminescence and beautiful colours fascinated not only the minds of wise men like Confucius, but also craftsmen who exploited these qualities as well as its flaws in creating objects of desire. Soon these became the pride of emperors of the medieval period. The evidence of earliest workings on jade comes from China, sometime in the Neolithic period, and it is the only country having a long and continued tradition of jade carving till date. Jade objects were also immensely popular with the Islamic rulers such as the Timurids of Central Asia, Safavids of Persia, Ottomans of Turkey and Mughals of India and in other cultures too.' Most of these rulers had fascination for jade and had commissioned variety of objects to be made in particular colour, texture, style and design. These objects reflect the distinctive style of their patron's taste. The main thrust here is to highlight the variety of jade objects created during the Sultanate and Mughal period, with special reference to collection housed in the National Museum of India. Etymology of Jade and its Popular Beliefs The English word 'Jade' is basically a misnomer that was derived from the Spanish terms Piedra de hijada meaning stone of the loins and Piedra de rinones meaning stone of the kidneys. Both of these terms were used after the belief of inhabitants of Mesoamerican civilization regarding curative powers possessed by jade, passed on to the Spanish Conquistadores in the 16th century. A similar word was also used by the French in the 17th century called l'ejade, most probably derived from the Spanish terms. The beauty of jade allured every culture but now here had it played a more significant role other than Asia. In China, jade was known as yu, the 'royal gem'. This gem par-excellence attracted the people of China and they also believe that it has several qualities. The few of them are jin means 'charity', gi refers to 'modesty', while yu signifies 'courage', ketsu symbolizes 'justice' and chi denote the 'wisdom'. Yasem is the term used for 'jade' in Persian language, which also included jasper and agate. The word yasab is used for jade in Hindi, which has been adopted from Arabic language. However, in Sanskrit or Hindi language no proper equivalent word for jade has been known so far. In Central Asia, it was referred to as Khas and the Turks called it Shootash. Greeks refer it as Nephros and in Latin it is known as Nephriticus. In ancient Egypt, jade was admired as the stone of love, inner peace, harmony and balance. Unlike the Chinese, who recognized certain virtues in jade, in India, apart from the sensuality of the material, jade was revered because it was believed to have possessed medicinal properties. It was thought that the liquor drunk from jade or agate cup allays palpitation of the heart and interestingly, a jade cup itself was believed to act as protection against poisoning. Furthermore, a heart patient was often advised to wear a jade amulet, known as hauladili. Jade: Its Variety and Source In scientific context to distinguish jade, is to dig deep into its mineral origin. This includes two main varieties according to their composition, i.e. Nephrite and Jadeite. The first variant, Nephrite, is a silicate of calcium and magnesium with its variation in colour caused by the amount of ferrous oxide (iron). In its pure form it is white in colour, but with the presence of iron its colour can vary to any shade of green, from light to dark. In China, jade in almost all occasion is referred to the Nephrite variety and much of it comes from the southern boundaries especially from the valleys of the rivers Kara-kash (Black Jade River) and Yarkand in the Kwen-Lun range. It is also found further north of the River Kashgar. The second variant, Jadeite, is a silicate of sodium and aluminium and is slightly harder than Nephrite. The presence of chromium results in the occurrence of brilliant emerald green and also has much wide range of colours than Nephrite. Jadeite is also found in the shades of mauve, yellow, blue, brown, red, white and grey. Since, Nephrite also comes in some of the mentioned colours, distinguishing Jadeite only through colour, can lead to wrong conclusions.3Most of the Jadeite comes from Mogaung district in Upper Burma and is also found in Shensi and Yunnan province of China and Tibet. In terms of their surface when polished, Nephrite reflects a more greasy lustre whereas jadeite, a glassy shine. Apart from these two main varieties of jade, there are also false jade and other varieties4 of semi-precious stones, which have been used for making different utility objects. 'False jade' or 'jade look like' stone comes from Bhera (in Shahpur of Punjab province, Pakistan), which is pure serpentine or bowenite, called by the natives as sangayasm. Being softer than jade it can be easily worked upon and there is also a belief that number of big size objects, which have been fashioned during the post Shah Jahan period, have been made out of this stone. Jade: In Indian Context In India, antiquity of jade goes back to Indus civilization (c. 2500-2000 BCE). Beads made of jade along with other materials such as jasper, carnelian, agate, serpentine, lapis lazuli, onyx, and so on, in different sizes and shapes have been reported from the various Indus sites and mounds. In fact, the etched carnelian (sard) beads with white designs were exported far and wide, and also highly prized.5 Though jade objects have not been reported from historical sites but a few crystal caskets for keeping relics have been found at Piprahawa (Uttar Pradesh), Bhilsa (Madhya Pradesh), Sopara (Maharashtra), Mirpur-Khas (Pakistan) and Shah-ji-ki-Dheri (Pakistan). All these objects testify a rich Indian lapidary tradition. From Archaeological and literary evidences, it is well known that finished items of chalcedony, onyx, etc. were exported in great quantity to Rome during 1st and 2nd dcentury CE. Perilous says that vessels made of precious stones were brought from Ujjain to Broach for exporting them to Egypt. Sanskrit and medieval literature also describe the uses of precious stones for image making. The finds of various medieval archaeological sites also confirm the use of semi-precious and precious stone beads for ornaments. A few stone vessels have also been reported which were most probably, used for ritualistic purposes only. The use of jade, from bead to objects, was extended during the medieval period. Several beautiful artefacts were made during Sultanate and Mughal period, which are preserved in museums world over. Some of the spectacular jade artefacts were created during the Mughal period. The most distinctive feature was the surface ornamentation on these jade artefacts. Technical Know-How Jade being a hard stone, can't cut in the sense of carving. It can be abraded only by another harder stone. The process of working on jade can be found explained in detail in the Chinese records. For abrading and cutting jade from a big jade boulder, four band saw made of iron wires, metal and wooden tools of different sizes and an abrasive mixture made of quartz, topaz, corundum and diamonds were employed. Then the jade fragment was cut into definite shape according to the size of the object to be fashioned. Later on, the required design was drawn on the smooth surface of the stone by the master craftsman with ink. Subsequently, other craftsmen executed the design using various tools, such as wire saw, drill and a grinding wheel. The diamond drill is used in scooping out the inner portions, preparing loops and ring handles, chains and to carve geometrical and figurative designs in low relief. Pao-Yao (precious powder) was used for polishing the objects, with the help of wooden and leather grinding wheels of different sizes. Sometimes wax coating is applied for a better result. Chinese jade is well known for its relief carving with flora-fauna, human figures and even architectural pattern, while the Indian jade is known for its surface ornamentation. Decorating the jade objects with precious and semi-precious stones is a special technique often used by the Indian artisans. The process of fashioning a jade object is difficult and time consuming, yet the Indian craftsman with a rich lapidary tradition, were able to give a new look to Jade carving which came to be popularly known as 'Indian Jade or Mughal Jade'. Jade artefacts created during the 16th century were in darker green colour, plain, simple but elegant. Slowly carving in relief became an integral part of these objects. Later on, the profuse use of inlaying gems and gold on the surface of jade objects can be seen. From Jahangir's reign jade show intricate and ornate workmanship which reached a point of excellence in the time of Shah Jahan. Use of gold sheet inlay on jade was also one of the important styles and the best example of it is an 18th century jade surahi (flask)' in the National Museum collection. The globular body with long neck surahi is inlaid with diamond-shaped small jade pieces surmounted with gold wire. Each of the joints is beautifully decorated with six petal flower motifs, which have been worked with gold leaf covering and glass. Precious gems like rubies, emeralds, uncut diamonds and semiprecious stones were also inlaid to synch these objects to the opulent surfaces of the buildings which were now decorated with intricate patterns in pietra-dura technique. In this method of surface ornamentation after making the required design, precious and semi-precious stones were inserted in sockets coated with glue along with lac. Then a thin gold or silver foil is used to secure the stone. Later golden wires were provided around the stones to reinforce their position. The use of enamelling (minakari) was also employed to surface ornamentation. It has been also further exploited to create an imitation of the inlaying technique. In this method, instead of using precious stones, enamel is used in the colours of gems, keeping the use of gold wire intact, to trick the eye to think it's inlaid with gems. Sometimes the surface of the enamel portion is incised with simple motifs imitate the carved rubies and emeralds. Besides inlay, enamel jade artefacts are decorated with etching and painting by the skilled Indian artisans. National Museum Collection of Jade Artefacts The collection of jade artefacts in National Museum is not very large compared to other museums, yet the variety within this small number allows scope and opportunity to study some of its important stylistic development in terms of ornamentation and objects. Small but significant collection has artefacts of different types, which can be broadly divided into four major groups; weaponry, utilitarian, jewellery and courtly lifestyle. There are also few artefacts with great significance, having inscribed the name of Sultanate and Mughal emperors. Another noteworthy aspect about the collection is that these objects represents the variety of ornamental techniques such as; simple carving, relief carving, stone inlaying, enamelling, etching and painting. Weaponry Medieval period emperor's love for weaponry is evident on jade hilts for daggers, swords and archer's ring. The hilts of the daggers were generally carved out of jade and with many of these daggers given away as gifts along with khilaat (robe of honour) mentioned in several entries to the personal memoirs' of the Mughal emperors, the style of these daggers were soon imitated beyond the Mughal court. In most of the miniature paintings of this period, khanjaras (daggers) and jamdhars (thrusting daggers) can be seen tucked away ostentatiously on the folds the pataka. Initially, these hilts were kept plain, where the elegance and simplicity was acknowledged through the colour and texture of jade. One such beautiful dagger in the collection known as pesa-kabza, with a plain deep green jade hilt, is a Persian style dagger probably introduced in India by the Mughals. In terms of its simple yet robust design, it suggests an early date of origin, somewhere in the 17th century. Near the joint of its Damascus steel blade on the jade hilt, it displays intricate foliate motifs in gold, achieved through koftgari (false damascening) technique.

Later on, these hilts were being carved in the shape of birds and animal's head and flowers, which gained immense popularity. The pommel of one of the hilts in the collection,sinuously ends with flowers buds emerging from long elongated leaves. The hilt is also ornamented with enamel and gold wire. Dagger with hilt carved in the form of a flower or a bud finds mention in Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri, the memoirs of Jahangir as phul-katara. Another hilt in the collection, probably of a straight dagger shows derived vegetal design with a forked pommel surmounted by a bud like button. As seen in the miniature paintings with their intricate husiyas (borders) where depiction of birds and animals as the main subject or as part of the khatayi (foliate arabesque with birds and animals), they too became popular subjects in the hilts. In the hilts, heads of animals such as deer, ram, horse, lion, tiger and even birds such as parrot were carved with great detail in jade. In the collection, the horse headed hilt of a khanjara (Fig.1) shows a magnificent thoroughbred with its mane gently falling over its neck.

Fig 1: Horse-headed hilt of khanjara (dagger), carved in relief, Late 17th century, Mughal, Northern India, Lt. 12.3, Wd. 6.7, Ht. 2cm , Acc.no. 54.59/1(b)

Next important part of this category is the wide range of zihgirs (archer's rings). The 'archer's ring' is a specially designed ring, which was worn by an archer in the thumb of the left hand at the time of archery. While pulling the string for shooting the arrow, it helps in safe-guarding the thumb, so that the string of the bow would not damage the fingers. Jade was a popular material although there are few in other materials like ivory, brass, gold, agate, emerald' (belonging to Nadir Shah made from an emerald taken from the treasury of Hindustan) and other stones which were used in making them. Some of these archer's rings are studded with gems, worked upon with enamelling and inlaying technique with intricate designs, of which a fine example is the one belonging to Prince Salim (later Jahangir). They too are often seen in miniature paintings dangling from the waistbands.' One of the archer's rings in the collection is carved in light translucent jade with leaf motifs in low relief is an artistic expression.

Utilitarian ArtefactsVarious objects of utility such as cups, plates, vases, spoons and even objects for storage were carved out of jade in the royal karakhanas (workshops), which is believed to have started with the Sultanate period and continued during the Mughal period onwards. The earliest jade utilitarian artefact in the museum's collection is a small hawan-dasta (mortal pestle), which is inscribed in Nastaliq script in Persian/Arabic language on both the outer walls of hawan (Fig.2). The first inscription on one side wall reads "Ya' Safi”, which means 'O almighty God', (who gives health). The other side wall illustrates "Banda-I-Khaksar Muhammad Qutab Shah", which refers 'Mohammad Qutub Shah, the ruler of Golconda'. The inscription indicates that this object once belonged to the imperial possession of Qutub Shah, the ruler of Golconda.

Fig 2: Hawan (mortal) inscribed with the name of Mohammad Qutub Shah, ruler of Golkonda, 17th century, Decean, Lt. 11.7, Wd. 6.7 cm, Acc.no. 59.236(a)

An English merchant William Hawkins visited the court of Jahangir in 1609 and estimated somewhere around 25 kilos of uncut jade in the royal treasury with more than 500 cups carved elaborately. He also adds that most of these might have been manufactured during Akbar's reign as it was only the fourth regnal year of Jahangir. One of the plates in a dark green Nephrite (Fig.3) dated to the last quarter of the 16th century is believed to be one of the few surviving jade objects from the reign of Akbar. The plate is shallow and is carved with the utmost simplicity devoid of any decorative motifs that is seen in objects of later period. Another object of utility, similar to the simplicity of the plate but definitely from a much later date is the spoon (Fig.4) delicately carved out of jade.

Fig 3: Shallow plate, last quarter of 16th century Mughal, Northern India, Dia. 24.3 cm, Acc.no. 59.14/43

Fig 4: Simple elegantly carved spoon, 18th century, Mughal, Northern India, Lt. 13.8, Wd. 2.7, Ht. 1.4 cm, Acc.no. 62.2938

Various shapes were explored by the artisans in creating these objects of utility. A small cup in the collection is carved out of jade with an interesting concept of bud which forms the handle. The field of the cup is carved with floral motifs of Mughal repertoire. A feature that is seen in most of these objects is that in terms of shapes, inspiration from nature such as leaves, flowers or shells is often used either literally or in a stylised manner. A dish in the form of a sea shell carved out of an almost white colour jade might have been used for serving mouth fresheners. Another interesting shape can be seen in a brownish colour jade of a shallow dish with handles containing rosettes. The body of the dish is also carved in a fully blossomed flower.Bowls of various kinds are also found in numbers, of which many seem to be wine cups, as often seen in the miniature paintings of Mughal period. One of the bowls, which is perfectly hemispherical in shape contains petal or leaf like motif carved in low relief, might have been a wine cup. The role of inscription is also very important although rare, as it gives out a clue about the date or in many cases, the owner's name. A small cup most probably a wine cup (Fig. 5) contains the inscription reading "Shah Akbar". It refers to Akbar II (r. 1806-37), who was the father of the last emperor Bahadur Shah II. The cup contains an intricate low relief carving of a chrysanthemum on the surface.

Fig 5: Cup inscribed with the name of Shah Akbar, Late 18th - Early 19th century, Mughal, Northern India, Dia.9.3, Ht. 5.5 cm, Acc.no. 61.506

In the category of objects of a more storage related function, one tumbler and a small cup like vessel with a lid are in the collection. Both the objects are remarkably carved with lids that fit perfectly on the mouth, and foliate motifs in low relief. The relief carving in these artefacts generally consist of stylised motifs such as rosettes, quatrefoils, to extremely sophisticated natural floral motifs comprising chrysanthemums, clematis, poppies, zinnias, roses and so on. A mirror frame in jade with the mirror now missing has profusely carved surface with floral motifs.The Indian artisans did not stop at just achieving excellence in carving interesting shapes in jade but went further in putting their own stamp, exploring various other surface ornamentation techniques. One of which was the inlaying technique with gems or enamel with reinforcements by gold wire. A bowl (Fig.6) is one of the finest examples in this category with its surface inlaid with uncut diamonds together with enamel and gold wire. Another example is the plate' with similar surface ornamentation, with replacement of diamonds by the use of jade pieces in darker colour, which are surmounted with gold wire.

Fig 6: Bowl with diamonds, enamel and gold wire, Late 18th - early 19th century, Mughal, Northern India, Dia. 13.5, Ht. 6.5 cm, Acc.no. 48.9/48

jewellery ItemsApart from utilitarian artefacts, the next important category is jewellery being made out of jade or by using it as a base for other stones. One of the examples is a bazubanda (armlet), carved out of jade and studded with emeralds and rubies. The stones also contain very low relief carving, a signature style of Mughal gems with gold paint around them. Inspired from the pietra-dura technique, a plaque (Fig.7) is inlaid with jade over jade. The concept is to play with the contrast between shades of jade create a sort of monochrome effect. Perfectly calibrated small pieces of dark green jade are cut according to the dictate of the design, to be inserted into the sockets. The use of gold wire for the boundaries and carving on these small jade components enhances the beauty of the plaque. Another object of self-adornment is a belt buckle carved intricately in the form of a flower with ruby studded at the centre. The buckle has a beautiful woven zari belt and the fineness of the object reflects its royal ownership in the 18th century. Apart from these, there are many examples of pendants studded with jewels which formed a common feature in this phase.

Fig 7: Plaque inlayed with darker jade , which is secured with gold wire, late 17th- early 18th century, Mughal, Northern India, Lt.4.5, Wd. 3.7, Ht. 0.1 cm, Acc.no. 48.9/4(2)

Painting in the real sense, was rarely done in jade objects, as the surface and colour of the jade in itself was so attractive that it would have been a waste to cover it. A very rare triangular plaque (Fig.8) encircled with small beads of rubies contains a scene where an ascetic is discoursing the king. Above these figures are inscriptions in Devanagari script, which reads "Kalidasa", "Vrksa (tree) tulasi ka and "king Pariksita Hastanagara" and a line from the verse of Hindi Poet Ghulam Nabi Raslin Bilgrami is all around the edges.

Fig 8: Triangular plaque painted with name of Kalidasa, vrksa tulasi ka, king Pariksita and verse from poet Ghulam Nabi Raslin Bilgrami and encircled with rubies, 19th century, Northern India, Lt. 13, Wd. 11.5 cm, Acc. no. 57.116/6

Objects of Courtly LifestyleThe higher luxury quotient of the objects in the fourth category generally suggesting to a more court or harem lifestyle, are clubbed together. The huqqa or hukah, an Iranian term for water pipes used for smoking tobacco, was gradually becoming a common feature at the courts and harem. It is also known as guda-gudi in Hindi and 'hubble-bubble' in English. It is believed that Portuguese had introduced tobacco smoking in India around 15th-16th century. The popular conception of smoking tobacco through water base being less harmful, led to its popularity during Akbar's period, although Akbar banned its practice. However, from Jahangir's reign onwards it became a common feature in the society. The rare narval shape huqqa (Figs.9, 9a, 9b) belonging to Jahangir himself is a masterpiece and displays the ingenious skill of the Indian craftsmen. The entire huqqa is made of jade very artistically, except small smoking pipe holder which is beautifully enamelled. The narval huqqa base is fixed on six legged stool with a long detachable smoking pipe and cilama (tobacco container). Rare and important Persian and Arabic inscription in Nastaliq script is on the upper edge and lower portion of the cilama as well as on pedestal's upper portion. The inscription on the cilama mentions the name "Padshah Jahangir" and the date "1032 Hijri" (1626 CE) along with beautiful couplets of Hazarat Amir Khusrau of 13th century. The pedestal is scribed with Surah Ikhlas from Holy texts.

Fig: 9a Fig: 9b

Two other later period huqqas from the collection are special not just for their attractiveness but for the technique of painting that is employed in their surface ornamentation. A small huqqa with a globular water flask and a surmounted cilama with lattice work contain lotus motifs painted on its surface using gold paint. The artist has restricted the gold painted lotuses to outlines in order to keep the sensuous surface of the pale jade revealed. Another huqqa base is painted again using gold paint in ajali (grilles or the lattice work pattern of Mughal jharokhas or windows) pattern and inlaid with turquoise beads.The muhanala (mouthpiece) is an important component of the huqqa. An interesting aspect of the mouthpiece is that a huqqa was shared in a gathering between groups, but everyone had their own personal muhanala. While smoking huqqa, these personal muhanalas were placed on to the smoking pipe, as it went passed on from one another. In a way this was a practice keeping in view the concept of personal hygiene. This aspect of the muhanala paved in way for exclusiveness and customisation in its design. There are muhanalas made of various materials as per the specifications of the user. On most occasions carved out of jade, there are simple ones or extremely flamboyant examples with elaborate inlaying and enamelling designs.

Fig 10: Canvara having jade handle with metal wires ending with silk tassels, carved, studded with precious stones, late 18th-early 19th century, Mughal, Northern India, Lt.43 (with handle & tassels), Wd. 3cm (handles upper portion) Acc.no. 57.99/1

Another object that forms an important part of the court insignia is the canvara (fly-whisk). It was more frequently manufactured in metal such as silver, but there are few exquisite surviving examples in jade. A relatively small canvara (Fig.10) is carved out of jade with flat metal wires with silk tassels in place of Yak hair. The handle is painted in gold with a chevron (zig-zag) pattern generally seen on the pilasters of the Ivan (gateway) or walls of Islamic monuments. The handle ends with an intricately carved floral opening which supports the flat metallic wires. This floral opening also contains intricate minakari (enamel) with gold wire ornamentation. Another object belonging to a similar family is the zafar-takia (armrest), whose handle is carved in ivory and painted with delicate geometric motifs and the final rest in jade. The jade rest contains floral patterns in relief.A technique such as incision was also employed in surface ornamentation, where the outline of the design or motif is incised onto the surface and filled with paint. The masaladana, a small box with compartments for storing spices or mouth fresheners (Fig.11), has floral motifs incised onto the lid and then filled with a black paint. In the central portion, it has a small turquoise bead inlaid to break the monotony and enhance the beauty. A similar object in the collection, although with a different surface ornamentation is a small yet striking gilauridana (box for keeping betel-nut). The pale pink enamel is placed amidst the gold wires to trick the eye for being rubies. This gilauridana also has well planned out segments to hold lime and other condiments used for chewing betel leafs.

Fig 11: Masaladana (spice box), engraving filled with colour and precious stone, 18th century, Northern India, Lt. 13.7, Wd. 10.1, Ht. 2.7 cm, Acc.no. 57.116/4

Carved hilts or cups, jewel's inlayed pendants or plates, enamel ornate bowl and plaque with beautiful painting are some of the important artefacts, are the prized possession of the National Museum. The lapidary tradition got mentioned in literature and also illustrated in the miniature paintings, especially in the royal portraits or picnic scenes. Original artefacts housed in museums world over and indirect narration in literature and paintings clearly reflects the medieval emperor's passion for jade artefacts. These beautiful and artistically created artefacts show the Indian jade carver's excellence, while on the other hand findings of several inscribed objects validate the emperor's pride. References- Markel Stephen mentions about the use of jade in Pre-Colombian Central and Mesoamerica and with the Maoris of New Zealand, The World of Jade, Marg Publications, Mumbai, 1992.

- Ibid., 4.

- Geoffrey, Wills. Jade of the East, New York: Weatherhill, 1981, p.15.

- Markel Stephan mentions at least thirty other varieties of semi-precious stones are known 'averturine quartz', 'beryl', 'jasper', 'bowenite' and several other serpentine, The World of Jade, Marg Publications, Mumbai, 1992.

- Gregory L. Possehl, The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, Vistane Publication, New Delhi, 2002, pp.95-97.

- William H. Schoff, The Periplus of the Erythrean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century (New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1912), chapter 48.

- Exhibition catalogue, Alamkara: 5000 years of Indian Art, Ahmedabad, 1994, p.62.

- Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur, Memoirs of Zehir-ed-din Muhammed Babur, Emperor of Hindustan, Trans. John Leyden and William Erskine, Annot., rev., Sir Lucas King. Vol.2, repr., Vintage Books, New Delhi, 1993, p.128.

- Nuruddin Muhammad Jahangir, Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri, or Memoirs of Jahangir, 2 Vols. in one, Trans. Alexander Rogers, ed. Henry Beveridge, Munshiram Manoharlal Publications, New Delhi, 1968, pp.396-397.

- The parrot headed dagger carved in 'mutton-fat' jade (white) is seen in the mid-18th century miniature paintings of Raja Balwant Singh, painted by Nainsukh, in Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai.

- Gul-Badan Begam, The History of Humayum (Humayun-Nama). Trans. Annette S. Beveridge, Atlantic Publishers and Distributers, New Delhi, 1990, pp.120-121.

- G.N. Pant and Yashodhara Agrawal, A Catalogue of Arms and Armour in Bharat Kala Bhavan, Parimal Publication, New Delhi, 1995, p.11.

- Linda York Leach, Mughal and other Indian Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library, Vol., Scorpion Cavendish, London, 1995, p.466.

- Exhibition catalogue, Gioielli dall'India dai Moghul al Novecento, in Galleria Ottavo Piano, Milano, 1996, p.187.

- Authors are thankful to Dr. Naseem Akhtar, former curator (Manuscript), National Museum, for reading the entire inscribed jade artefacts of the museum collection.

- W. Foster, ed. Early Travels in India, 1583-1619, London: Oxford, 1921, pp.102-103.

- Exhibition catalogue, Alamkara: 5000 years of Indian Art, p.62.

- Exhibition catalogue, "Treasures of Indian craftsmanship from the 16th to 19th century from the National Museum", New Delhi in the Albertinum Dresden State Art Collection, 1985, p.42.

- Dr. Naseem Akhtar et al, Islamic Art of India, Malaysia: Islamic Arts Museum, 2002, p.135.

- Exhibition catalogue, Gioielli dall'india dai Moghul al Novecento, in Galleria Ottavo Piano, Milano, 1996, p.186.

- The mid eighteenth century poet Ghulam Nabi Raslin Bilgrami's famous works Ang Darpan and Rasprabodh are preserved in the Rampur Raza Library.

- Dr. Naseem Akhtar et al, 2002, p.136.

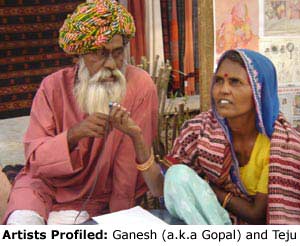

JOGI ARTGanesh and Teju are renowned world over for their folk music and art. The couple are folk artists that belong to the Pauva caste, also known as Jogi or Bharathari. Traditionally they moved from place to place-singing traditional folk and devotional songs at dawn. Today, this multi-talented couple is known internationally for their music and a form of art unique to them and their family- Jogi Art. |

| Birth of Jogi Art Haku Shah, a famous Indian artist and anthropologist, is responsible for the couple’s initiation into art. He frequently lived in the village where Ganesh and Teju lived, and after about five or six years of noticing him in their village, Ganesh arranged to meet him through a common friend – this was almost thirty years ago.Ganesh’s meeting with Haku Shah developed into a long association between the two. After singing a bhajan for Haku Shah, he was given a paper and pen and asked to draw. That was Ganesh’s first drawing ever, and is published in a book on him called Gopal. A few years later, encouraged by Haku Shah once again, Ganesh was encouraged to bring his wife Teju to draw with him, and together the couple under Haku Shah’s guidance gave birth to an art form unique to them. What is Jogi Art? Jogi Art is a unique art form that is named after the Jogi community that its creators- Ganesh and Teju belong to. The paintings by Ganesh and Teju are made using basic tools, such as a ballpoint pen and paper. However, their paintings have evolved over time, and today they paint on paper, cloth using not just blue/black ink, but also color. They have also started painting using cotton or cloth on a stick. The paintings are a reflection of the artists’ lives, with motifs from their daily lives appearing in their paintings- scenes from their village, the sun, sky, the earth, pictures of goddesses. The artists take inspiration from the songs they sing, their traditional stories, Indian mythology and the things they see around them. Usually, their paintings are composed on a single sheet of paper or cloth. Recently, while working on a painting based on the Ramayana, they decided to work on a single large sheet of canvas to accommodate all the images. The couple continues to experiment and improve their art. They recently tried working on canvas instead of paper, but found the medium unsuitable to their style, and financially unviable. About Ganesh and Teju Ganesh and Teju are vibrant, talented people and their paintings reflect this. With eight children, Teju reminisces about when her children were young and she would be happiest painting with her children around her or on her lap. The family works hard to develop their art and make a living off it at the same time. Even though their paintings are sold across the globe, making a living isn’t easy. The family lives off the income earned by the sale of their paintings, while they work on more paintings, sometimes, the children work as laborers to make ends meet. The whole family works in unison, handling the housework, the paintings as well as ensuring there is enough income to meet their basic needs. Ganesh and Teju have come a long way from traveling from place to place, singing songs to people at dawn, but they haven’t forgotten their music, it continues to be a part of their lives and their art. |

| 1 Teju Zeichnet, Aus Den Malheften einer indischen familie, Christina Brunner and Cornelia Vogelsanger with contributions by Haku Shah und Elisabeth Grossmann (Teju Zeichnet, Aus Den Malheften einer indischen familie, Christina Brunner and Cornelia Vogelsanger mit Beitragen von Haku Shah und Elisabeth Grossmann) |

|

|

|

|

|

|