JOURNAL ARCHIVE

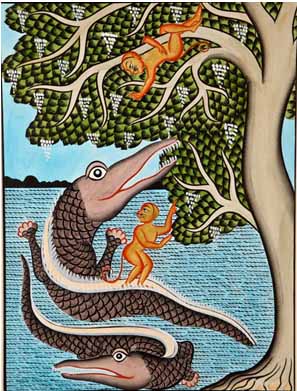

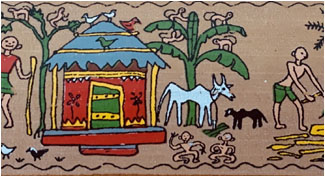

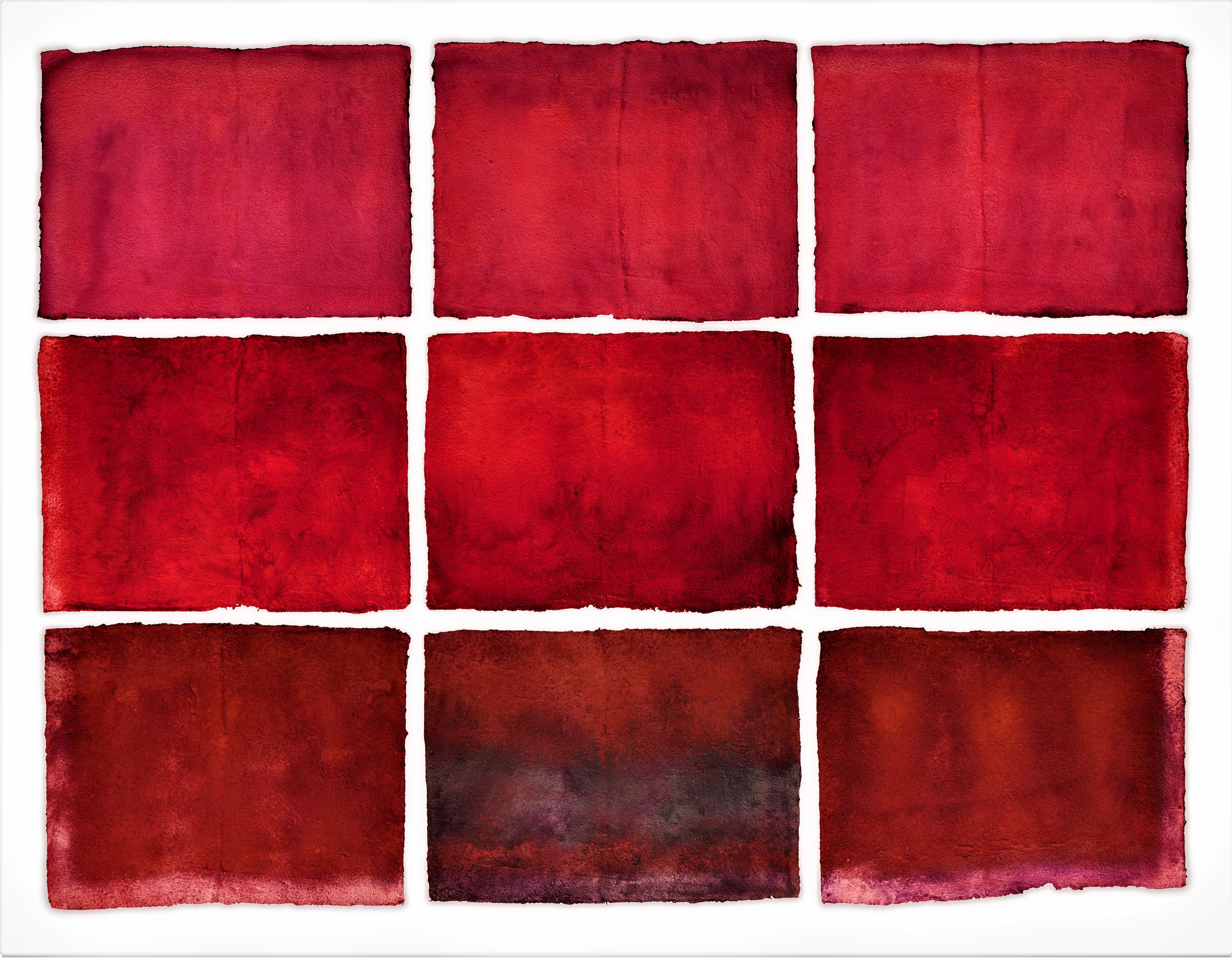

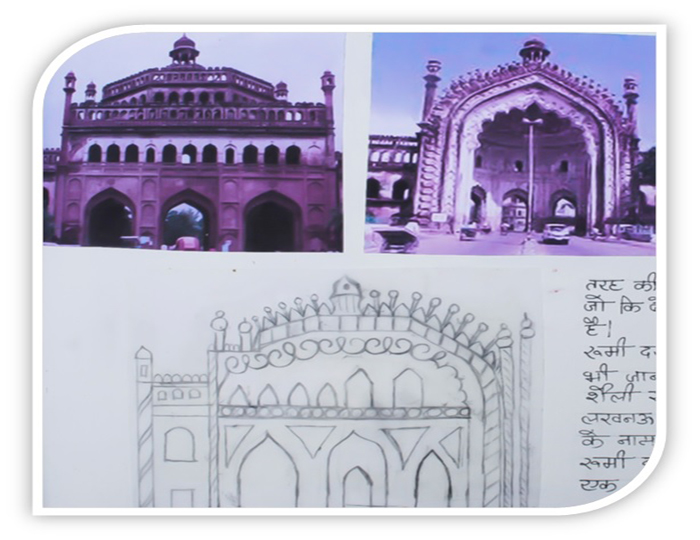

The "pahari rumal" or "chamba rumal" is the term used for embroidered coverlet in the Punjab Hills of Himalayan region (present Himachal Pradesh) in around eighteenth-nineteenth centuries. These rumals are embroidered with colourful floss silk threads on muslin or white cotton cloth (sometimes also red). Embroidered in double satin stitch these reversible rumals are the creation of women residing in this area in their leisure time. They used to produce these beautiful rumals to cover the gifts offered to God, bride and bridegroom on religious and ceremonial occasions. There are a few pahari paintings in which embroidered rumals have been depicted as coverlet. Two such excellent examples of miniature paintings are in the collection of the State Museum, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, and National Museum, New Delhi. In both the paintings of Pahari school, female devotees have been shown holding offering to God, which are covered with embroidered rumal. Apart from coverlet, these rumals are also used as handkerchief, as head dress6 and sometimes as patka (sash). The most fascinating aspect of these rumals is the depiction of vast subject theme, which is not usually found in any other kind of embroidered rumals. In the religious category of Pahari rumal, the famous religious themes are: Rasa, Krishna with flute, Krishna-Balarama-Subhadra," Rukmani Harana," Krishna, Holy Family, Gajantaka Shiva, Hanuman, Ganesha, Sakti, etc. Apart from religious category, wedding scene is the next important theme which often finds occurrence on embroidered pahari rumals. Some of the famous weddings depicted in rumals are: Krishna-Rukmani, Shiva-Parvati, Rama-Sita and Raja Jita Singh's (of Chamba) wedding with Rani Sarada Devi (of Jammu)." Besides these religious and wedding themes, there are rumals which illustrate hunting scene, floral and geometric pattern, etc. All these rumals are pictorially very beautiful and elegant due to which these had attracted the attention of art lovers and scholars. The rich subject theme and intricate embroidery, puts them in the category of classical style rumals. However, there is another very distinct category, which is different from the earlier ones and is known as folk style of rumals. In this group the folk element is reflected very prominently. The limited subject, bright colour, imbalanced composition and uneven long stitches are the features represented in these folk rumals. Although most of the museums have large number of folk style rumals in their collections the quality found in the classical rumals is much superior. Hence, the Pahari rumals have made a special place in the group of embroideries practised in Himachal Pradesh." Most of the scholars are of the opinion that rich tradition of painting done on paper, cloth and wall of this region might have inspired the women for embroidering the same subject on rumal. The strong line work and use of soft soothing colours are the main focus points of these rumals. When composition of rumal, is found in miniature paintings or wall paintings, it gives the impression that probably court artists of Pahari schools might have done the drawing on these rumals and even provided the supervision for colour scheme. Few such rumals like Nayaka-nayika-bheda, Krishna playing flute, holy family, Gajantaka Shiva, Rukmani-Harana and Rasa have been compared and studied by some scholars. The present paper is an attempt to look at some such rumals, housed in the collection of the National Museum, New Delhi. RAMA-SITA WORSHIPPED BY HANUMAN The impact of bhakti from 12th to 16th century and its acceptance by the masses was a factor that helped to sustain the manuscript and painting tradition of mythological subjects, through to the late 19th century."' People's great devotion to Rama influences the bhakti poets, cult leaders, epic poets and artists, who paint the theme on paper and wall. Some such subjects appearing in miniature paintings, have been beautifully embroidered on rumals also. The concept of enthroned Rama-Sita or Ramapattabhisekam is one such subject, which was popular all over India from North to South." Pahari artists have used this subject for miniature painting and wall painting, which has been copied on rumals by embroiderer. National Museum has white square muslin rumal, which is beautifully embroidered with Rama-Sita theme. Rama, incarnation of Lord Vishnu, and Sita, his wife, are sitting on throne and being worshipped by Hanuman in criss-cross narrow border frame (Pl. 19.1). The narrow border of the rumal has been worked with colourful floral pattern. The royal couple is sitting under chhatri (umbrella) and a small stool is placed near their feet. Hanuman is standing in front of them, while the chauri-bearer is standing at the back. A pair of peacocks, cyprus trees and other trees give the effect of Himalayan region. Powerful line drawing, use of metal thread and subdued colour indicate its workmanship of Chamba Kangra style of mid-eighteenth century. Similar subject, with much elaborate narration, has been embroidered on a Pahari rumal hanging which is in the collection of Chandigarh Museum. Although threads and colours of this rumal have faded at places, even then its charm has not been lost because of its superb composition, which gives the proper three-dimensional effect. It depicts Rama-Sita seated on throne and the coronation ceremony is being witnessed by a number of gods and courtesans. The heavenly gods, from boat-shaped Viman (vehicle of god) are showering flower-petals from the top while musicians and dancers are enjoying the occasion of Rama's coronation. The armed guards stand outside the palace and well dressed people around the pond give the royal ambience. The theme of Rama's coronation is often found in painting also. National Museum has a miniature painting (Kangra-Sikh style, nineteenth century) and wall painting (of Chamba Rang Mahal, eighteenth century) illustrating the same theme (Pl. 19.2). Composition in both the paintings illustrates the same subject and similar kind of treatment in which Rama-Sita are seated on a throne under umbrella. Hanuman is standing/sitting in front of Rama-Sita and the chauri-bearer is at the back and depiction of utensils is the other prominent feature of this composition. In the miniature painting, three princes, dressed in royal attire, are standing at the back and holding morchhal (fly-whisk made of peacock feather), weapon and danda (standard); probably they are the brothers of Rama. A similar depiction is found in the Chandigarh's rumal/hanging. In all the three examples, artist has not changed the main subject (Rama-Sita seated on throne). The only difference among miniature painting, wall painting and embroidered rumal is the treatment of the outer frame. In the case of wall painting, it has an arched frame; the miniature painting has oval frame, while the rumal has a criss-cross frame. Artists had followed the trend of their respective medium. The strong line work in this Pahari rumal embroidered with soft colours reminds one of the Pahari miniature of Kangra-Sikh style. LIFE SCENES OF KRISHNA The Vaishnava poetry of Jayadeva, Vidyapati, Chaitanya, Suradasa and Mirabai ranging from 12th century to 16th centuries found expression in paintings from the 17th-19th centuries in the Pahari paintings. Some of these paintings became the main inspirational source for women to embroider the same subject on cotton rumals. One such rumal is in the collection of the National Museum, which illustrates the life scenes from Krishna's life in a very interesting way. A small red rumal is divided in three rows and each row is further sub-divided in three compartments, which makes up nine divisions in all (Pl. 19.3). These divisions are uneven in size, something like a chaupar spread and each division depicts the life scenes of Krishna. Govardhandhari Krishna and baby Krishna with mother Yashoda have been embroidered in corner divisions in two rows. These two scenes have been repeated in diagonal compartments in opposite directions. In embroidery it is difficult to create three-dimensional effect, but here with the help of black outline on Govardhan Mountain, the artist has successfully been able to produce the effect of illusion. Four-armed Govardhandhari Krishna is playing on flute and is flanked by gopis on either side. Baby Krishna and gopis are standing near mother Yashoda, who is churning the butter. In between four big scenes, there are four smaller divisions; each one illustrates Krishna's different aspects. Baby Krishna with mother Yashoda represents his childhood (in repeat), while Krishna-Radha in rain represents his youth and along Krishna with Balarama depicts his divinity aspects. This rumal has some interesting features like its unique composition, depiction of several subjects in a single frame and use of red colour background cloth. Usually Pahari rumals depict a single subject, which can be viewed from one direction only, while here the artist has depicted more than one subject and that too embroidered in such a way that it could be viewed from all directions. There are few such rumals in which elephant rider, Ganesha or Vishnu has been depicted in four/two different directions. Although these rumals also illustrate the composition of figures in different directions, these are single figure themes not the thematic narration. In the National Museum's rumal, depiction of Krishna's life scenes has been done with several human figures composed in different directions. Secondly, there is use of red colour cotton fabric instead of white cloth, which is less popular. Lahore Museum (Pakistan) has eighteenth century rumal having a red background, which depicts Ganesha seated under a canopy. Dr. V.C. Ohri suggests that use of red colour fabric for Chamba rumals is the tradition of Bilaspur or Mandi school rumals. The Mandi school depicts less Bhagavata theme in comparison to Bilaspur school. The illustration of Bhagavata theme, colour scheme, and narration of mountain appears to be the work of Bilaspur style line work, so it be Pahari embroidered Rumal done in probably Bilaspur style. Other important features of this rumal are: depiction of Balarama in the Krishna-Balarama division, illustration of architecture in Yashoda's churning division and Radha's costume and umbrella in Krishna's rain depiction division. The use of zari threads, for making compartments and for depicting jewellery of necklace, bangles, and bajuband makes this rumal rich. Use of blue and yellow silk thread along with black outline for illustrating figure work and silver gota on the edges makes it attractive. Krishna lifting mountain Govardhan, mother Yasodha churing butter and Radha-Krishna in rain are the famous themes often found in Pahari miniature paintings. A wall painting in the Chamba Rang Mahal depicts Radha-Krishna in rain. On the backdrop of mountain and dark clouds Radha-Krishna stand under an umbrella within an arched frame. Good line work and colourful attire makes it attractive. Floral creeper border around the wall painting reminds one of the border frame of Pahari rumals, which is the most essential and integral part of rumal. The embroiderer has used the subject theme of miniature painting, border of wall painting to create this rumal. However, embroidery work has its own limitation; therefore, the work of embroidery is not so fine as in a miniature or wall paintings. WEDDING OF SHIVA-PARVATI Wedding scene is yet another favourite theme of Pahari women, which they have often embroidered on the Pahari rumals. These rumals illustrate the celestial wedding of god-goddess and sometimes the royal wedding. Among celestial weddings, the popular ones are Krishna-Rukamani, Rama-Sita and Shiva-Parvati and the wedding of Raja Jita Singh of Chamba with Rani Sarada Devi of Jammu is the famous royal wedding. These rumals are important as they are a visual evidence of cultural history, matrimonial alliances, traditional costumes and social customs of a particular community and region. In the collection of National Museum, there is a rumal which illustrates the wedding of Shiva-Parvati (Pl. 19.5). This celestial wedding is being witnessed by Lord Brahma, Lord Vishnu, Ganas of Shiva and several other people. The wedding scene has been embroidered within a square centre frame, which is surrounded by a broad border of floral creeper. The bride and bridegroom are sitting under mandapa, which is decorated with parrots. This type of mandapa was very popular, as it can be noticed in a number of miniature paintings of this phase. Three-headed Brahma wears white clothes and Vishnu has been depicted in a red dhoti. They are standing in the centre of the mandapa and facing the bridegroom, Shiva. The wedding rituals have been witnessed by people standing around the bridal couple as well as people watching from windows of the palace. The man standing behind the groom wears red turban, long jama and blue sash, which resemble Kangra-Sikh school with effect of Jammu style of attire. Some people standing behind the groom's side, have animal head (horse?) instead of human. Musicians are at the back and playing musical instruments. Men and women behind the bride are wearing Kangra style turban, sash, jama and peshwaz, odhani, etc. A few people are walking near the wall, dressed in similar attire. The presence of Brahma and Vishnu inside the mandapa and depiction of horse-faced female figures behind the bridegroom gives the impression that this could be the wedding of Shiva-Parvati. Apart from embroidered rumal, the National Museum also has a rumal, painted on cloth, which depicts the wedding scene (Pl. 19.6). This off-white square rumal depicts bride and bridegroom in the centre and it is surrounded by divinities, musicians, elephants, horses, dowry, palanquins, etc. The bridal couple is sitting on a stool under the mandapa, which has been decorated with lots of parrots, and they hold each other's hand. A man dressed in jama, turban, sash and paijama, standing at the back of the bride seems to be the father of bride. The couple is surrounded by several women, who hold chhatari (umbrella), banner and chauri (fly-whisk). Some of them are sitting in the corner and playing various instruments. Different types of utensils, cot and chair are placed around the mandapa, as a part of marriage function. The upper portion of rumal has been worked out in small compartments, which depict Ganesha in centre and Sun, Moon and Rahu-Ketu around. The lower portion of rumal illustrates two palanquins, open and covered, for bridegroom and bride, respectively, and elephants, horses, musicians, banner and standard holders have been depicted around. Both embroidered and painted rumals have some similarities like composition of wedding scene, mandapa decorated with parrots, depiction of architectural dwelling, utensils placed near the bridal couple. Presence of Brahma and Vishnu, in embroidered rumal signifies the marriage of Shiva, Parvati and people dressed in colourful attire, in the painted rumal appear to be wedding of some royal personality. GAJANTAKA SHIVA Shaivite Gajantaka Shiva theme has been beautifully illustrated on white handspun yarn and hand-woven cotton cloth, which has been delicately embroidered with floss silk threads. The story of Gajantaka Shiva has been mentioned in many Puranas, here this rumal unfolds the same story, which is based on Shiva Purana. Entire Gajantaka theme has been embroidered within a rectangular frame, which starts from lower frame and moves upwards (Pl. 19.7). Done in narrative style, the artist had wisely chosen the three incidents to communicate the story. The lowermost portion depicts seven Shiva Ganas holding weapons, i.e., stick, battle-axe, rod, etc. and running after Gajasura who is chasing Nandi (the vehicle of Lord Shiva) and Lord Shiva is also trying to help Nandi. In the next sequence, demon Gajasura in his ferocious mood is chasing Nandi and Lord Shiva is running towards Nandi for rescue, while Paravati and her other female attendants are also running to help Nandi. Finally in the third scene, Lord Shiva and Parvati are shown seated on lion skin under the big tree, while Gaja's skin is lying on his shoulder. The uppermost portion illustrates a few gods and goddesses in their viman (vehicle), descending from heaven and showering the flowers on Shiva-Parvati and bowing before them with respect as he had killed asura. Shiva is embroidered with white, grey and pink coloured silk threads. He is adorned with a snake and holds stage/flag and damaru (small drum) in his two hands. Parvati and her attendants wear the orange/yellow/magenta pink lahanga-choli-odhani (long skirt-blouse-head covering) and usual ornaments. Kartikeya is represented by depiction of peacock in the scene. Line work of this coverlet is of a high quality, as the charcoal line work is clearly visual at places. On the whole, with such a high quality selective subject having good composition, strong line drawing work, good quality stitch work and wonderful colour balance makes this coverlet a very good example. It appears that it could be the line work of Guler Kangra artist and made for someone special, probably on order. The best part of this embroidered rumal is that it appears to be a copy of a Guler style of miniature painting (Pl. 19.8), which also illustrates the identical subject and more importantly in almost similar composition. This Guler painting also depicts the story of Gajantaka in narrative form. Here the miniature painting artist had used only two sequences: the first sequence illustrates Gajasura chasing Nandi, and Lord Shiva is shown helping Nandi and trying to tame demon Gaja, while in the second scene Shiva-Parvati are sitting under a tree on a lion skin and have covered themselves with Gaja skin. Kartikeya and Ganesha with their respective vehicles have been shown around. The entire story line has been developed around mountains, trees and clouds in embroidered rumal and miniature painting both, which is an interesting, striking and natural feature of the Pahari work of art. Gajantaka Shiva theme on Guler painting and embroidered rumal featuring Guler/Kangra style is an unusual finding. It is rare to have similar subjects done in two different mediums. HOLY FAMILY Shiva, Parvati, Ganesha and Kartikeya form the Holy family in Hindu pantheon, which became the popular subject for eighteenth-nineteenth centuries Pahari artists, to illustrate it in various mediums. The National Museum has an embroidered Pahari rumal, miniature painting on paper and wall painting depicting the holy family theme almost in a similar fashion. The coarse cotton nineteenth century rumal has been embroidered with holy family and Bhairava in the centre surrounded by a broad border (Pl. 19.9). The colourful floral creeper border is almost at the edges. Two-armed Shiva-Parvati sit together on a spread of lion skin and Shiva holds damaru and trisula having pataka (banner) in it. Parvati is dressed in lahanga-choli-odhani and jewellery like bangles and nose-ring, while three-eyed Shiva is also adorned with ornaments such as ear-ring, bangles and snake necklace. Kartikeya has been embroidered with six heads and six arms; Ganesha carries modaka and axe and Bhairava holds arms bowl and stick/sword. All of them have been shown with their vahanas: Nandi, lion, peacock, mouse and dog for Shiva, Parvati, Kartikeya, Ganesha and Bhairava, respectively. There are some interesting features in this rumal like depiction of Bhairava, crowned Ganesha (may be embroidery artist was a great devotee of him), nose-ring of Parvati (a common feature of Pahari women), and use of colour suitable on each God. He has composed the scene of winter night as White Mountain represents snow; moon, fire and tong indicate the dark cold night scene. This rumal appears to be a late nineteenth century work done in Chamba style, which is often found in miniature and wall paintings. A wall painting of Chamba Rang Mahal depicts Shiva-Parvati sitting on lion skin under a tree, at the backdrop of a mountain (P1. 19.10). The scene has been composed under an arched top, surrounded by floral border. It a beautiful illustration of Shiva as a loving father, where Ganesha is sitting on his lap and Kartikeya is also close to him. Parvati is looking towards Shiva with admiration. Their vahanas; Nandi, lion, peacock, and rat — are also embroidered nearby. Vaishnava, Bhagavata and Shaivite religion and literature have inspired the Pahari artists to create miniature paintings, which influenced the artist to create wall paintings in this region. These paintings might have inspired the women, in respect of caste, region and class, to do the embroidery work on rumal, hangings, choli, hand-fan, pillow cover, chaupar spread, etc. Among all the embroideries, rumals that too of classical style, became very popular. The intricate embroidery, soft soothing colours and pictorial qualities of these rumals have created a special place. All these qualities give the impression that women might have taken help from court artists for line drawing work and colour scheme. Although these classical rumals illustrate flora-fauna and hunting theme also, the picturesque qualities makes them unparalleled and outstanding. NOTES AND REFERENCES 1. Dr. Subhashini Aryan has suggested the term 'Pahari rumal', in her work (Himachal Embroidery, 1976, Delhi, p. 13). These embroidered rumals (coverlets) are not confined to Chamba region only. These are made all around the Himalayan region, such as Nurpur, Bhaohli, Kangra, Bilaspur, Mandi, etc., and therefore it is better to use the term Pahari rumals like Pahari paintings. 2. Chandigarh Museum has Rama's coronation hanging, which has inscription in Devanagari. It reads that this rumal was embroidered by Champakali, a palace maid. 3. A 19th century Kangra painting illustrates five sages and princess worshipping Shiva Lingam. It depicts women holding tray, which are covered with rumal (Dr. Daljeet, Immortal Miniatures, Delhi, 2002, p.106). A hanging depicting Mahabharata is a gift by Raja Gopal of Chamba in 1883. (Margaret, Hall, The Victoria and Albert Museum's Mahabharata Hanging, South Asian Studies 12, 1996, pp. 83-96) 4. M.S. Randhawa, Kangra Paintings of Bhagavat Purana, New Delhi, 1960, pl. xii; Dr. Daljeet, ibid p. 97 5. B.N. Goswamy and E. Fisher, Pahari Masters, Delhi, 1997, p. 198, p. 199. 6. K. Zarin, Chamba rumals in the Collection of Lahore Museum, Lahore Museum Bulletin, (ed.) S.R. Dar, Vol. 1, no. 1, Jan. June 1988, p. 11. 7. B.N. Goswamy, "Threads and Pigment: Rumals and Paintings in the Pahaii. Tradition', pp. 4-6, in exhibition catalogue; Rasa: The Chamba Rumal, New Delhi, 1999. 8. Other prominent variety of embroidered rumals is: chikan work of Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh; chakla of Gujarat, colourful rumal of banjara women and rumala from Punjab. In chikan rumals white cotton cloth is embroidered with white cotton thread, which illustrates floral and creeper patterns.Chakla is made of colourful satin silk cloth, which is embroidered with silk thread and generally it illustrates rasa or floral patterns. Cotton rumals, embroidered with colourful cotton threads, are used by women on the occasions of dances. Patterns are geometric and use of cowrie shells makes it beautiful. Rumala is usually satin silk rumal, which is embroidered with silk thread and depicts Guru Nanak Dev and other Sikh Gums. 9. A. Pathak, 'Rasa in Indian Textiles', National Museum Bulletin, no. 9, New Delhi, pp. 20-29. 10. A.K. Bhattacharya, Chamba Rumal, Calcutta, 1968, p. 22. 11. Ibid., p. 34. 12. J. Jain and Aarti Agrawal, National Museum of Handicraft and Handloom, Ahmedabad, 1989, p. 152. 13. A. Pathak, 'Holy Family Embroidered on Chamba Rumal', Puratan, No. 7, Bhopal, 1989-90, pp.136-138. 14. A. Pathak, 'A Unique Chamba Rumal on the Gajantaka Theme', Marg, Vol. 55, Number 3, March 2004. 15. Bhattacharya, ibid, p. 16. 16. Ibid., p. 36-45. 17. H. Geotz, An Early Basohli Chamba Rumal: The Wedding of Raja Jita Singh of Chamba and Rani Sarada Devi of Jammu AD 1783', Bulletin of the Baroda State Museum, Vol. III, Part 1, 1945-46, pp. 35-42. 18. The major museums having Pahari rumals are — Bhuri Singh Museum, Chamba, Himachal Pradesh; Calico Museum, Ahmadabad, Gujarat; Cincinnati Museum, U.S.A.; National Handicraft and Handloom Museum, New Delhi; Himachal State Museum, Shimla; Indian Museum, Kolkata, Lahore Museum, Lahore, National Museum, New Delhi; Victoria and Albert Museum, London. 19. Apart from rumals, Pahari women used to do the embroidery work on wall hangings, costumes, fans, chaupar, chapal (slippers), etc. John Irwin, Indian Embroideries, 1973, Ahmedabad; Aryan, ibid p. 22. 20. B.N. Goswamy and Eberhard Fischer, Pahari Masters, Zurich, 1992. 21. Tanjore and Mysore painting of south India, wood carving of Tamil Nadu, kalamkari painting on cloth of Andhra Pradesh and ivory carving of Mysore are some important art works of south India, while painted patta and terracotta of Bengal, miniature painting of Rajasthan, and stone sculptural evidences are from north India. 22. B.N. Goswamy, Piety and Splendour, Sikh Heritage in Art, Delhi, 2000, p. 230. 23. S.S. Kapur, `Chamba Wall Paintings', in The Times of India, Annual, Bombay, 1966, p. 63. 24. P. Banerjee, Krishna in Indian Art, Delhi, 1978. 25. Chaupar is a board game, which has a cross shape having some blocks and played by four people with the help of sixteen gamesmen and three dies. 26. Aryan, ibid., pl. 4; 44, 46. 27. Zarina, ibid., p. 16. 28. V.C. Ohri, The Technique of Pahari Painting, Delhi, 2001, p. 122. 29. W.G. Archer, Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills, Vol. I, Delhi, 1973, p. 86; Dr. Daljeet and Dr. P.C. Jain., Krishna (in Hindi), Delhi, 2002, p. 92. 30. Kurma Purana, A.S. Gupta, Varanasi, 1972, Vol. 31, pp. 16-18; Varaha Purana, A.S. Gupta, Varanasi, 1981, pp. 15-18 and Shiva Purana, J.L. Shastri, Varanasi, Part II, Khanda V, Ch. 57. 31. Kapur, ibid., p. 65.

PANCHATANTRA

Why choose the Panchatantra as a theme for an exhibition of art? What is contemporary about a collection of animal fables that is over 2000 years old?

Visnusarma, its author and renowned sage speaks to us over the ages to tell us why:

Whosoever learns this work by heart,

Or through the story-tellers art,

Will never face defeat

Even if his foe

The King of Heaven be.

Charged with igniting the minds of three dull-witted princes whose political education was consigned to his charge Visnusarma’s Panchatantra has not yet finished saying what it has to say. Its philosophy, both profound and practical remains relevant today, not only for aspiring princelings and political hopefuls but for the rest of us as well.

This marvelous text on political thought niti shastra and the wise conduct of life comes to us fresh and vibrant over the millennia’s, its complexities cloaked in fables. The prose punctuated with maxims, proverbs and other wisdoms, the stories framed within stories, leading us on and enfolding into other stories.

Didactically powerful the five discourses of the Panchatantra stakeout a vast territory of statecraft. Book one covers the Loss of friends and discord among allies; Book two on Securing allies, winning friends; Book three is on War and peace; Book 4: On loosing what has been gained and the final discourse in Book V is on Hasty Actions and Rash Deeds.

Though the social, economic, political and popular pressures would have been very different when first imparted over two millennia ago, Vishnusarma’s teachings continue to resonate today as he begins to educate in order that

“No one undertake a deed

Ill considered, ill conceived,

Ill examined, ill done...”

While applying pedagogy to educate and awaken a seeking mind Vishnusarma additionally provides guidelines to the foundational principles from which an educator too can learn a lesson or two

Since verbal science has no final end

Since life is short and obstacles impend

Let central facts be picked and firmly fixed

Like swans that extract milk from water mixed.

Visnusarma at the end of the six months given to him makes good his boast of awakening the minds of the three dullards making them aware not only of niti shastra but teaching them

Better with the learned dwell

Even though it be in hell

Then with vulgar spirits roam

Palaces that kings call home

Over the millennia the source text of the Panchatantra with its universal truths spread across the boundaries of the sub-continent to be told and retold in the many tongues of travelers and courts and from teller to teller. The recensions of the fables are evident from the adaptations and versions that multiplied in the telling, which not including the numerous languages and dialects of the subcontinent itself, are said to be over two hundred in number, in more than fifty languages. From a Pehlevi version (550-578 CE) to a 570 CE Syriac one and then the Arabic Kalilahwa Dimnah dated to 750 CE; traveling further to medieval Europe and the Fables of Bidpai and thence to the German Das der Buch Beyspiele (1483), the Italian La Moral Philosophia (1552) and on to its influence on Aesops Fables, the Fables of La Fontaine, the Grimm Brothers tales and others. Altered to suit audiences and differing cultural milieus, adapting to the changing centuries remaining ageless in its sheer widespread popular appeal.

This exhibition refocuses our attention on this ageless and universal core of this great text and its continuing and continuous appeal two millennia later, schooling us, as he did the princes, on how to think and not on what to think.

GURUPADA CHIRAKAR |

For if there be no mind

Debating good and ill,

And if religion send

No challenge to the will,

….

How would you draw a line betwixt

Man-beast and the beast?

Tracing the Lineage

The intersection of the Panchatantra and the narration of epics, fables, stories and religious tenets through art has a long enduring antiquity. Evidence from the 3rd Century BCE attests to this ancient telling of tales through their visual imaginings.

ANWAR CHITRAKAR |

The link reinforced by literary evidence from the 4th Century Chitrasutra of VishnudharmottaraPurana. This great treatise on painting and image-making sets out the ideals and theories of painting, it states “Even religious teachers use paintings as the most popular means of communication that could be understood by the illiterate and the child”

From ancient India to the eleventh century the trend continued, adapting over the centuries to its times with the emergence of a new more personalized format of visual narration, the illustrated manuscript. This tradition took a hold on the imagination and from the development of the narrative manuscripts in Buddhist monasteries to the Jain texts that led to the setting up of great libraries with artists commissioned to illustrate canonical literature including the Kalpasutra and Kalakacarya Katha.

In medieval India the intersection between art and narration continued to flourish in the court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar (1556-1605). The enormous outpouring of illustrated manuscripts from the artistic studios established during his rule were eclectic in nature mirroring the Emperors own interests. From classical Persian literature to the great Hindu epics; from history, poetry and fables to stories from the Kathasaritsagar to the Tutinama, and to the best known of all, the Hamzanama were all illustrated. Included too in the long list was the very subject of this exhibition –the Panchatantra.

A parallel popular tradition with an equally long antiquity fulfilled similar aims, the visual narratives integral to the process of transmitting knowledge. Itinerant picture-narrators known by various names such as Saubhikas, Yamapatakas, Mankhas, Chitrakathis, Pratimadharins, Vagjivanusing scrolls and single sheet pictures dramatized didactic stories. As early as the second and first centuries BCE epic tales and dramas were being performed by itinerants who traveled across villages, acting and reciting stories from the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist traditions, from epics and from local legends.

The ancient Jain text the Bhagvata Sutra tells of legendary sage of the Ajivaka sect Mankaliputta Goshala, a contemporary of Mahavira and the Buddha who as the son of a Mankha was trained in the profession. Mankhas are mentioned in several other Jain Prakrit texts with the canonical text Ovaiya including them in its list of public entertainers.

|

|

|

Venkataraman Singh |

Purna Chandra |

|

|

| Premola Ghose | Mohan Kumar Verma |

Panini, the Indian grammarian of the fourth century BCE, refers to itinerant Brahmins, the Saubhikas, who earned their living by displaying religious images and by singing of the tales. Kautilya’s treatise on statecraft, the Arthasastra (c. 350 BCE) recognized the potential of the Mankha picture-reciters as spies, moving freely as they did from place to place. Both Patanjali’s Mahabhasya(140 BCE)and the Buddhist text Mahavastu (2nd century BCE- 4thcentury CE)refer to Saubhikaswho used pictures for their performances. With Bana’sHarshacharita (7th century CE) providing a vivid portrayal of the Yamapatika in a bazaar narrating from a painted picture scroll the retribution awaiting the wrong-doer in the next world

In the 12th Century Someshvara III the renowned Sanskrit scholar and Western Chalukya king in his great classic Manasollasa covered a wide range of subjects from kingship to the arts, statesOne who narrates a story with the help of paintings is a great Chitrakathak.

This custom of combining the visual with narrative is in continuum over the millennia’s. The Bards in Rajasthan recite the legendary exploits of the folklore hero Pabuji with the unfolding of the Phad scroll, the Jadu-patua of the Santhals, the Garoda picture-reciters in Gujarat, the Nakashi in Andhra, the Patua scroll painters and poets of Bengal, the Paithan Chitrakathi and this exhibition at the IIC continue to ignite minds, speaking not only to princes but to all of us - today.

Here at the India International Centre

The Panchatantra with its root in all our childhoods is renewed here at the India International Centre in New Delhi as this exhibition - ‘Painted Fables’ brings back a quality of new beginnings, enriching us all with fresh pleasure.

|

|

|

Prakash Joshi |

NoorjehanChitrakar |

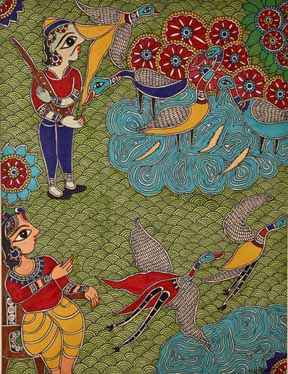

Despite their widely differing individual styles and diverse cultural geographies the artists here share a certain bond - the Panchatantra itself, its fables forming a part of their childhood universe. Therein lies the exhibitions remarkable unity and consistency. All the varied manifestations held together, inspired by this shared beginning, all contributing to the richness of the offering.

The choices of the fables selected include not only old favorites, but the lesser remembered ones. Containing within their story-lines the essence of the frame that hold the narrative threads together within the structure of the five discourses.

As in the fables the values that this collection of artworks is concerned with include the fundamentals philosophies that govern earthly power, glory, worldly pleasures, political life, duty and action. Outlining the perils residing in the trusting of an enemy and the pitfalls of depending on false friends, drawing a fine balance between virtue and vice; the time and place for shrewd strategy to counter brute force, reality and causality. Questions of existence and illusion; of impermanence and the eternal; the significance of action versus repose. The ethics of wise living and moral teachings communicated within individual frames and by the exhibition as a whole.

This exhibition full of humor and wisdom, vivid in anthropomorphism and rich in human detail is peopled with kings, queens, ascetics, merchants, princesses, Brahmins , aam-admi and of course with animals standing in for human types, pinpointing human morals. The animals as metaphors and key to understanding the abstract principles of Niti Shastra and the wise way to lead life, helping us identify the cunning of the fox, the craftiness of the crab, the lion as king, the foolishness of donkeys, the selfishness of swans, the sneak in the jackal et al.

Within each frame of this richly imagined exhibition the artists open the gateway to the wonder that is Visnusarmas Panchatantra, engaging us like the princes of yore, to ask with bated breath, what happens next?

|

|

|

BharatiDayal (Madhubani) |

BharatiDayal (Madhubani) |

Note written for the exhibition Painted Fables. India International Centre (IIC), New Delhi - February 2014.

Exhibition Conceived by Gulshan Nanda, and organized in collaboration with IIC, Delhi Crafts Council and the Craft Revival Trust

The Poetics and Politics of Indian Folk and Tribal Art

Issue #005, Summer, 2020 ISSN: 2581- 9410

Long before modern modes of storytelling were available, religious preachers and artist-storytellers in many parts of India would travel from village to village singing folk, religious and moral stories illustrated in brightly painted scrolls. In the eastern part of India, two styles of this visual and performing art developed, one in Bengal and one in Odisha. The pattachitra, as the style was called, derived its nomenclature from Sanskrit, where ‘patta’ means cloth, and ‘chitra’ means painting. In Odisha, three painting traditions developed based on mediums used -- bhitichitra (wall paintings), tala pattachitra, (paintings on palm leaf) and pattachitra, (paintings on cloth). Stylistically, the tala pattachitra and the pattachitra are similar, with palm leaf paintings being of earlier origin since palm leaf manuscripts pertaining to Hindu, Buddhist and Jaina traditions were often illustrated. Shanta Acharya, an eminent poet from Odisha speaks of the ancient roots of pattachitra in her poem Painter of Gods“Tracing our ancestors back to the eighth century, When the painting of pattachitras as souvenirs For pilgrims turned into profession, And the craft was passed down generations, father instilled in me a hunger for perfection - A work of art being the true worship of the divine.”

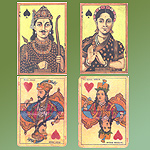

Interestingly, even though these art styles had been in existence for centuries, the establishment of the Jagannath Temple at Puri in 12th century CE brought them into prominence. These paintings evolved to serve specific ritual purposes in the temple, and some were painted as souvenirs for pilgrims and visitors. Only one community, the Chitrakaras, who believe they are the descendants of the cosmic architect, Vishwakarma can make these ritual paintings. The Chitrakaras have three groups or badas – the Jagannatha Bada, the Balabhadra Bada, and the Subhadra Bada, each associated with one of the three deities of the Puri temple triad – Jagannath (Krishna), Balabhadra (Balarama, Krishna’s elder brother), and Subhadra (their sister). The badas create paintings associated with their deity and are responsible for the requisite repainting of the images of the deities for the annual ratha yatra (chariot festival) in Puri. Pattachitra paintings usually depict themes from mythology, particularly stories about Jagannatha and Lord Vishnu including his dashavatara (ten incarnations) as well as episodes from the Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Other popular themes include the story of Buddha’s life and the Jataka tales and occasionally some folk stories. Stylistically, the paintings can be recognised by the characteristic beak like noses, beautifully elongated eyes, prominent chins on figures and stylised trees. The Chitrakaras use natural colours in accordance to strictures laid down in the Shilpshastras which are taught to each practicing artist. According to these canons, blue is for Krishna, yellow for the goddesses, white for the gods, light blue or white for Sri Ramachandra and yellow for the garments of Krishna (pitambar). The artists are free to use their creativity while choosing colours for garments of secular figures and gods and goddesses. Shanta Acharya in Painter of Gods eloquently shares the process of preparing colours.Father taught me all about colour –

conch shells for white, lamp soot for black,

yellow from the hartala stone, vermilion from cinnabar,

green a gift from the leaves of the neem tree,

blue from indigo and the khandaneela stone.

We made paintbrushes with keya root –

the finer brushes with carved wooden

handles have mouse hair. A dozen long hairs at the centre

give it a needle-point edge when dipped in paint.

The art of making the pattachitra is passed from one generation to the next, the knowledge and the skill of painting being important factors for even arranging marriage. The process of pattachitra painting begins with an arduous preparation of the cloth on which it is painted. As Shanta Acharya describes itIt takes five days for the spirit of the gods to descend,

for the readiness of the canvas –

from soaking the tamarind seeds in water,

grinding it to a thick pulp in a mortar,

stirring the paste on a gentle fire

until left with a residue,

the glue to stick two layers of cloth, cotton or tussar,

before buffing it with the fine powder of the soft clay stone from the Nilgiri mountains

that lends the piece its unique colour.

Once dried in the sun it is cut and polished

with a semi-precious stone,

then with a smooth pebble or piece of wood.

I’ve followed this ritual since my childhood.

Painting begins only when the cloth has been fully prepared. Earlier, there was a marked gendered division of labour in the making of the pattas, with women preparing the cloth while the men painted. In recent times, there are many more women artists. One factor has been the increasing use of tussar silk in place of the burnished cotton cloth since the early 1980s which has given women more time to pursue painting. The process of creating tala pattachitra or palm leaf paintings is also quite elaborate and involves great skill and dexterity. The delicate palm leaves are first carefully dried to provide a hard base for the drawings. The prepared palm leaves are then sewn together to become a foldable scroll. The artist then uses a sharp stylus to etch the paintings on the palm leaves. Colour, traditionally black, is smeared all over the leaf and gets deposited in the engraved grooves. The rest of the colour is wiped off, leaving only the etched part coloured in black. The artists have to be very skilled -- care has to be taken to exert the right amount of pressure while using the stylus– too much and the leaf will tear, too little, then the colour will adhere to the groove. Since the pattachitra traditions of Odisha developed around the cult of Jagannatha, the main artist clusters are in Puri, Raghurajpur and Bhubaneshwar. The Chitrakaras create scrolls for specific temple rituals. The anasara patti is painted on the occasion of Debasana Purnima, when it is believed that the gods and the goddess have a ritualistic bath, to beat the heat of summer. The story continues that because of the bath, the deities fall sick for a fortnight, and have to rest in a chamber called the anasara ghara, due to which the devotees are unable to worship the main idols, and are denied darshan. In place of the idols, the anasara patti, which is painted with large images of the main deities, is worshipped by the devotees. The Jagannatha temple also commissions the Krishna patti, which is worshipped on his birthday, Janmashtami. The Bamana Patti, celebrating the Vamana avatara or incarnation of Vishnu, is worshipped on his birthday, and the Kandarpa Patti, worshipping Kandarpa, the god of love, Kamadeva is worshipped. In addition to creating pattachitras for the Jagannath Puri temple, Chitrakaras also create paintings for personal use by devout Hindus. The Yama patti (the painting of Yama, the god of death), and Usha Kothi (depicting the story of the goddess, Mangala) are pattachitras, worshipped by women in Odisha. The artists also create paintings for the market such as the Jatripattis made exclusively pilgrims to the Jagannath Temple. Different types of Jatripattis are made - the anguthi paintings are circular and ring sized, the gola paintings, also circular but bigger in size depict the panchamandira (five shrines) of Puri, and the sankhanavi which depicts the Jagannath Puri temple on a conch shell. A popular ancient Indian card game, Ganjifa, consists of cards painted with Indian deities. The pattachitra artists also paint the cards for Ganjapa, as it is known in the region, for the elite to play. Life in Odisha, just like many other parts of India, revolves around religion, with Puri being one of the main centres of pilgrimage for Hindus, and Bhubaneshwar, the adjoining district and capital of the state, having more than 300 historic temples. The pattachitra is intertwined with the religious life of the people, and hence has become an inseparable part of the rituals. During weddings as well, the brides are married with the Jautuka pedi, a trousseau box adorned with pattachitra paintings. The Odisha pattachitra painting tradition has clearly been sustained by the religious narratives and rituals surrounding it. Unlike the Bengali style, the Odisha pattachitra has retained its form over the centuries and has remained free from any outside influences. Today, this indigenous style of painting continues to flourish, supported greatly by the religious tourism in Puri and government initiatives such as the establishment of heritage art village in Raghurajpur.The need for covering the floors of the houses with cotton rather than woollen spreads popular in Persia, brought in the durree and the khes. The hangings in the colourful tents led to the invention of the floral designs on rough cloth. The textiles for use in ceremonials became even more variegated under the Mughals; the animated bright colours of Haryana fabrics are likely to spread more and more to the entire world, as the drabness of the 'technology-run-mad' syndrome demands richness for the eyes. Panipat, a historical town of India, presently known as a city of Handloom was once famous for its khes weaving. These were woven in a double-cloth weave with cotton yarn, making it thick enough to be used as a shawl or a wrap. It was more popularly used as a bedding material. With the advent of the power-loom, the handloom sector of Panipat suffered a setback. However, while the carpet and durree weaving industries survived, khes weaving died out owing to its time consuming complex weaving.

1: RESEARCH OUTLINE

1. 1. Study Area This study focuses on the Panipat district of Haryana. There are regions in nearby Uttar Pradesh where khes is still being woven, but Panipat was chosen to study the traditional Panipat khes craft, which came, along with the weavers from that region, to India from the West Pakistan region after the Partition of 1947. 1. 2. Objectives

-

To study the geographical background of the region.

-

To study the historical background of the craft and the area.

-

To understand the social, cultural, and economic structure of the craft pocket.

-

To study the production process in detail, including material, tools, equipments and techniques.

-

To study design and quality.

-

To study the marketing scenario of the craft.

-

To identify different issues in the craft pocket.

-

To critically analyse the observations and recommend alternatives in the identified problem areas.

-

Field visits: Field studies were conducted by visiting handloom factories at Panipat. Power-loom factories working for export market were also visited since most of the entrepreneurs were traditional weavers who had come from Pakistan after partition and were a vital source of information.

-

Interviews: First generation immigrants from Pakistan were interviewed for they had come as weavers, had prospered to become entrepreneurs and had also seen the complete growth and decline cycle of khes weaving in Panipat. Industrialists were also interviewed to understand the present scenario of the handloom industry.

-

Observation: Visiting the factories at Panipat revealed that the condition of the weavers had changed drastically. The demands of the export market from the handloom sector also showed possible reason behind the death of the double cloth khes while the handloom sector prospered.

-

Photography: The traditional khes were available only in personal collections, whereas replicas of the traditional khes were made by the Weaver's Service Centre, Panipat.

-

Sketching And Drawing

-

Collection Of Samples: Since traditional kind of double cloth Khes were not available in the local market, these were made to order for sample. Samples of the raw material were also collected.

- Books And Journals: Various libraries were visited in Delhi to find out the route and source of introduction of the traditional khes in India. An intensive study of the pre-partition gazetteers was done to find out the various missing links in the history of khes weaving.

- Official Sources: Concerned government officers and other people were also interviewed to get the details of the various policies that have been implemented in the handloom sector and their effect.

- Museums

2: THE CRAFT

2.1. Evolution of The Craft The term khes has traditionally been used to describe any thick cotton cloth used as a spread or upper garment. It included a great variety of fabric worn by all classes in the Punjab. The North-western part of the country, particularly Multan Division of undivided Punjab before partition of India was known as the birthplace of khes. Noted centres of khes weaving included Dera Jat, Dera Ismail Khan, Jhang, Multan, Shahpur Kohat, Peshawar, Muzaffargarh, Lahore, Karnal, Ludhinia, and Patiala. The centres of great perfection were Multan, Shahpur Bhera, and the Khushaab in the Shahpur district and at Jhelum. Woven by the weavers, both Hindus and Muslims, as well as by some Kabir panthis also, the khes was in equal favour with the Sikh Sardar and the Musalman Jatt.

Traditionally the local people procured the khes for their requirements on barter system.

The good quality of the khes of the region had remained undisputed since 1888 as T.N. Mukherjee states in his Art Manufactures of India: in the context of comparing it to a Rampur khes which had won a gold medal at the Calcutta International Exhibition, Mukherjee states that though the Rampur Khes is not surpassed by any handwork in India, it is not as good as those woven in the Punjab.

Woven by the weavers, both Hindus and Muslims, as well as by some Kabir panthis also, the khes was in equal favour with the Sikh Sardar and the Musalman Jatt.

Traditionally the local people procured the khes for their requirements on barter system.

The good quality of the khes of the region had remained undisputed since 1888 as T.N. Mukherjee states in his Art Manufactures of India: in the context of comparing it to a Rampur khes which had won a gold medal at the Calcutta International Exhibition, Mukherjee states that though the Rampur Khes is not surpassed by any handwork in India, it is not as good as those woven in the Punjab.

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, Panipat stood witness to three extremely decisive battles. The first was that of the Babar, the founder of the Mughal Empire, against Ibrahim Lodi, the Pathan King of Delhi in 1526 A.D.; the second of his grandson, the young Akbar, out to wrest his father's shaky dominion from the Hindu general, Hemchandra, 30 years later in 1556; and the third of the Marathas and Ahmad Shah Abdali in 1761. In 1803, the power of the Marathas in North India was completely broken and Karnal district, including the present Panipat district, with Daulat Rao Scindia's other possessions west of the Yamuna, passed on to the British, by the treaty of Surji Arjungaon, signed on 30 December 1803. The district which was considered then to be 'the most turbulent district in the North-West Province' did not give as much trouble as was expected during the Uprising of 1857.

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, Panipat stood witness to three extremely decisive battles. The first was that of the Babar, the founder of the Mughal Empire, against Ibrahim Lodi, the Pathan King of Delhi in 1526 A.D.; the second of his grandson, the young Akbar, out to wrest his father's shaky dominion from the Hindu general, Hemchandra, 30 years later in 1556; and the third of the Marathas and Ahmad Shah Abdali in 1761. In 1803, the power of the Marathas in North India was completely broken and Karnal district, including the present Panipat district, with Daulat Rao Scindia's other possessions west of the Yamuna, passed on to the British, by the treaty of Surji Arjungaon, signed on 30 December 1803. The district which was considered then to be 'the most turbulent district in the North-West Province' did not give as much trouble as was expected during the Uprising of 1857.

| Name of Tehsil | No. of Villages | Name of Town |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The district is located 29º 23' 33'' North Latitude and 76º 58' 38" East Longitude.

| Population according to 1991 census | = 8,33,501 |

|

= 4,49,504 |

|

= 3, 83,997 |

-

The district has a sub-tropical continental monsoon climate, with hot summer, cool winter, unreliable rainfall and great variation in temperature.

SALIENT FEATURES OF PANIPAT'S INDUSTRIES:

-

Panipat is exporting about 50 per cent of the total export of the handloom products of the country.

-

Panipat has been awarded Gold Trophy by the Export Promotion Council for the highest export of the woollen hand tufted carpets.

-

The handloom industry of Panipat is meeting out 75 per cent demand of the barrack blankets of Indian Military.

-

Panipat town has got the distinction of having the maximum number of cotton thread or shoddy (rough yarn) spinning units at one particular place not only in the country but also in the world.

-

The pickle industry of the district of international fame; the Pachranga achara of Panipat is being exported to the Middle East European countries.

-

Samalkha, a small town of the district is nucleus place of the foundries and finds its name on the industrial map of the country.

Small-scale units, including those set up under Cottage and Village Rural Industries Scheme, account for 10,172 registered units. With the investment of Rs 640.80 crores, these units provide employment to 46,201 persons. The items manufactured by these units include handloom products,textiles (power loom and spinning), chemicals, engineering goods, electrical goods, leather and leather products, hosiery products, readymade garments, wood products, non-ferrous products, food products/agro-based products, paper and paper products, service industries, synthetic, tapestries, etc. Out of these 10,172 small-scale units, 1,400 units are under rural industries scheme. The items manufactured by them include cotton synthetic, blended fabrics, tapestry, woollen carpets and wooden furniture.

- CHARKHA

The bobbin or the pirn is fitted on the charkha s kept on the right of the swift. This is usually made of metal bicycle wheel, with a small metal or wooden handle in the centre of the wheel, to rotate it in clockwise direction. On the left hand side of the wheel, a metal spindle, having a pulley in its centre is fitted. A thick cotton cord is used to connect the large wheel to the pulley. When the wheel is rotated the spindle also revolves automatically.

- SWIFT This is a rotatable mound made of wood with a horizontal central axis, linked to six non- adjustable arms on either sides. The hank or lachhi is put on this with the loose end tied to a bobbin or pirns.

- WARP DRUM

This is a 5-5.5feet tall wooden rotatable mound with a horizontal central axis with non adjustable arms on either sides. These are connected to each other on either side. These are connected to each other with wooden arms on which the yarn gets wound.

- HECK

Heck is a wooden frame with a comb-like structure, through which the yarns from the bobbins on the creel passes to be wound on the warp drum.

- PIRNS Pirns are usually 2-3 inches long, made of wood or plastic, and used to wind the weft yarn on. It is then fitted inside the shuttle.

- BOBBINS

Bobbins are about 5 inches long, made of plastic and used to wind the warp yarn on.

- CREEL The creel is a rectangular wooden frame with an arrangement of thin metal rods, to hold the bobbins, jutting out from the space between the two arms.

-

WARP YARN WINDING The hank is put on the swift with the loose ends tied to a bobbin which is put on the metal spindle of the charkha. The handle of the charkha is rotated in a clockwise motion to fill the bobbin.

- WEFT YARN WINDING If the weft is required of the same colour the pirns are fitted on the metal spindle of the charkha and the yarn is supplied from the bobbin which was filled earlier. If a different colour is required the same method is followed as for the warp yarn winding.

- WARPING The yarn from the bobbin is wound on the warp beam, which is similar to a large bobbin. An uninterrupted length of hundreds of warp yarn results, all lying parallel to one another. The length of the warp yarns has to be decided in advance.

-

PIT LOOM Traditionally a khes was woven on a pit-loom in which the weaver sits on the edge of the pit with his legs working on the treadles inside the pit. In the given diagram of a horizontal Indian loom A is the warp, B and B1 are two healds hanging over a supporting bar C. The two healds are connected with two heald horses or sticks D and D1. E and F are cloth and warp beams respectively. G and G1 are the cords which connect the healds with two treadles placed inside a pit, and H is the pit. P and P1 are two pulleys suspended from a cross bar C on the top of the loom.

In this loom the weaver throws a shuttle through the shed from one selvedge end across the width of the cloth by one hand, and catches the same at the opposite selvedge and by the other hand. This operation is repeated so long as the entire piece of fabric is woven.

The yarn for the woof or weft (bana) is welted, and wound on a small hollow spools, generally straws. The shuttle is shaped like a small boat pointed at each end, and having the intermediate space open. In this space the spool of yarn is placed and revolves on a wire which runs through it lengthwise. The end of the yarn passes out through a hole in the side of the shuttle.

This loom had been known to be in use in India 5,000 to 6,000 years BC and the uses of the reed, lease rods and temples were also known to the weavers by that time. But its production is considerably slow, say, 3 to 5 meters a day of 8 working hours, or in weaving finer fabrics still lower.

In this loom the weaver throws a shuttle through the shed from one selvedge end across the width of the cloth by one hand, and catches the same at the opposite selvedge and by the other hand. This operation is repeated so long as the entire piece of fabric is woven.

The yarn for the woof or weft (bana) is welted, and wound on a small hollow spools, generally straws. The shuttle is shaped like a small boat pointed at each end, and having the intermediate space open. In this space the spool of yarn is placed and revolves on a wire which runs through it lengthwise. The end of the yarn passes out through a hole in the side of the shuttle.

This loom had been known to be in use in India 5,000 to 6,000 years BC and the uses of the reed, lease rods and temples were also known to the weavers by that time. But its production is considerably slow, say, 3 to 5 meters a day of 8 working hours, or in weaving finer fabrics still lower. -

FLY-SHUTTLE FRAME LOOM

A fly shuttle frame loom or four poster fly shuttle loom is made of heavy wooden framing having an overhung slay. This loom is fitted over the floor with fixed pegs. A and B are the two healds connected to two treadles C and D. Cords from heald A pass over two pulleys E and F to the heald B. The slay G holds two shuttle boxes at two ends and is suspended from the top of the loom by means of two slay swords H and H1. I is the warp beam, J is the backrest, K is the reed, and L is the cloth beam. M is where the weaver sits and weaves.

A fly shuttle frame loom or four poster fly shuttle loom is made of heavy wooden framing having an overhung slay. This loom is fitted over the floor with fixed pegs. A and B are the two healds connected to two treadles C and D. Cords from heald A pass over two pulleys E and F to the heald B. The slay G holds two shuttle boxes at two ends and is suspended from the top of the loom by means of two slay swords H and H1. I is the warp beam, J is the backrest, K is the reed, and L is the cloth beam. M is where the weaver sits and weaves.

-

It has an increased speed as one hand of the weaver operates the picking handle, and the other hand remains free to operate the slay.

-

Fabrics of long width can be as conveniently woven as the narrow ones.

-

Large number of healds can conveniently be operated.

-

The structure of the loom is more compact and solid and it vibrates less. It can give more production, better quality of cloth and higher efficiency.

-

Let-off is done with a pawl and lever arrangement which can be operated by a weaver from his seat when the cloth is taken up on to the cloth beam at intervals.

-

It can be worked with dobby or jacquard attachment, which is mounted on the top of the loom frame.

-

It is suitable for weaving both fine and coarse fabrics.

-

DRAFTING The warp yarns are passed through the healds according to the desired design.

-

DENTING The warp yarns from the healds are passed through the reed.

2.13. Technique Khes weaving, a complicated compound weave with a double set of warp threads, is today a specialty of Haryana. This technique was practised all over Punjab in undivided India, the finest being from Multan (now in Pakistan). The khes was traditionally woven in double weave or double cloth, which is an unusual technique in which the front and back are actually woven as independent layers, one above the other, occasionally swapping places to inter link and create a pattern. Two sets of warps are set up one above the other and the weft is interchanged at the edge so that they are transferred from the upper layer to the lower layer of the fabric and vice versa. Both the warp and the weft can be interchanged. This results in the formation of common points of interlacing spread over the length and width of the fabric. Double cloth produced in this way have the same patterns on both sides, but with the colours interchanged, one face of the fabric is the negative of the other.

Sometimes a khes is also woven in a dense twill weave with very fine diagonal lines running all over the fabric. It is a balanced two up, two down twill with single set of warp and weft but both in a combination of colours, thus forming beautiful checks.

Khes is woven as a plain fabric in a balanced two up, two down twill with a single colour yarn used both in the warp and weft.

Earlier varieties of khes were woven using hand-spun yarn in warp and weft, which is equal to 2s or 3s in warp and 6s, 8s, or 10s in weft. Hank sizing was done to provide strength to the single ply warps and because two ply of single yarn was used in weft, these khes pieces were called do sutti. Generally in the regions of its origin, it was woven on smaller looms having reed space of 28 to 30 inches. Then to bring the khes to normal size of 54 x 90 inches or 60 x 90 inches, two or three width were stitched together. It was also known as Char Paira Khes as it was woven using four paddles in a loom. Slowly weavers started using mill-spun yarn in both warp and weft: common counts are 2/6s, 2/10s, 2/20s for warp, and 4s, 6s, 10s for weft, etc. Around 1950, when khes came to India with the weavers from West Pakistan and Multan it started being made on fly-shuttle frame looms.

Later, the jacquard machine was introduced for making figurative designs on the khes. This type of khes woven on plain double cloth principle and sometimes with rib effect were also popular. These also came to be known as Panipat Khes.

Sometimes a khes is also woven in a dense twill weave with very fine diagonal lines running all over the fabric. It is a balanced two up, two down twill with single set of warp and weft but both in a combination of colours, thus forming beautiful checks.

Khes is woven as a plain fabric in a balanced two up, two down twill with a single colour yarn used both in the warp and weft.

Earlier varieties of khes were woven using hand-spun yarn in warp and weft, which is equal to 2s or 3s in warp and 6s, 8s, or 10s in weft. Hank sizing was done to provide strength to the single ply warps and because two ply of single yarn was used in weft, these khes pieces were called do sutti. Generally in the regions of its origin, it was woven on smaller looms having reed space of 28 to 30 inches. Then to bring the khes to normal size of 54 x 90 inches or 60 x 90 inches, two or three width were stitched together. It was also known as Char Paira Khes as it was woven using four paddles in a loom. Slowly weavers started using mill-spun yarn in both warp and weft: common counts are 2/6s, 2/10s, 2/20s for warp, and 4s, 6s, 10s for weft, etc. Around 1950, when khes came to India with the weavers from West Pakistan and Multan it started being made on fly-shuttle frame looms.

Later, the jacquard machine was introduced for making figurative designs on the khes. This type of khes woven on plain double cloth principle and sometimes with rib effect were also popular. These also came to be known as Panipat Khes.

-

Char paira: In which 4 peddles are used in the loom for making the khes.

-

Aath paira: In which 8 peddles are used in the loom for making the khes.

-

Ek sutti: In which single ply of untwisted yarn is used.

-

Do sutti: In which double ply of untwisted yarn is used.

-

Do tahi: If by folding into two, or one across, the khes fits an ordinary sized charpai (bed)

-

Chau tahi: If it is so large that it requires to be folded in four to make it the size of the bed.

-

-

Sada Baafi: When the pattern is all in lines or checks and runs either straight down or straight across the webs.

-

Khes Baafi: Where the pattern may be either plain or check, but the thread of the weft entwined alternately with those of the warp, so that the make of the fabric appears to be diagonal or corner-wise across the fabric, instead of the threads crossing at right angles.

-

Bulbul Chashm Baafi: Where the fabric is damasked with a pattern of diamond shapes produced by interweaving the threads of warp and wefts. These are worn by the more wealthy who can afford them.

-

Khes Chandana: Black and white khes; pattern is of alternate diamond shapes of black and white.

-

Khes Gadra: A khes in which thread of two colours are woven together in a large check like a plaid shawl.

-

Khes Char Khana: Common check khes.

-

Other than losing its market, Khes has also lost its identity. Since the very beginning the Khes was popularly used as a bedding material. It was used as one of the layers along with chindi dari and bed sheets. Later with time when the original khes was

replaced by other kind of fabrics, these also, because of the similar usage were called khes. So, a figurative double cloth fabric woven on a jacquard loom is also called a khes, whereas in the early mentions of khes there is no description of a figurative khes, the only patterns

that were made traditionally and the only designs possible on a handloom were a combination of checks and stripes.

Other than losing its market, Khes has also lost its identity. Since the very beginning the Khes was popularly used as a bedding material. It was used as one of the layers along with chindi dari and bed sheets. Later with time when the original khes was

replaced by other kind of fabrics, these also, because of the similar usage were called khes. So, a figurative double cloth fabric woven on a jacquard loom is also called a khes, whereas in the early mentions of khes there is no description of a figurative khes, the only patterns

that were made traditionally and the only designs possible on a handloom were a combination of checks and stripes.

SOME SUGGESTIONS TO REVIVE THE DEAD CRAFT:

-

Change the target market Khes used to be sold in the local market for household consumption and it did not had the grandeur of a craft product because of its use. Khes should be aimed at the high end niche market, which has a better purchasing power.

-

Alter the look of the khes Traditionally colours of the khes were of great significance. Khes with blue stripes in the border was preferred by Muslims and that with red stripes was preferred by Hindus. The names of some of the khes like Khes Chandana (black and white khes) were based on the colours of the yarns used to weave it. The colours should be based on the demand of the market it is aimed at.

-

Improve the finish of the khes Since khes was woven and sold in pairs of two, the warps between the pairs was left uncut, and the loose ends unfinished. To add to the value of the khes the warps between the pairs should be cut and loose ends should be knotted.

-

Diversify the raw material being used Since khes was mainly meant for the household purpose it was made in cotton, then the cheapest and the most easily available yarn. But early descriptions reveal that khes was also woven in silk with gold borders for the zamidaars, the high-end market of yesteryears. There is a need to revive the rich look of the khes. Also, the product range should be different for varied market segments.

Askari, Nasreen & Liz Arthur, Uncut Cloth

Banerjee, N. N., Weaving Mechanism

Bhatt, S C., District Gazetters of India, 1997

Dhamija, Jasleen & Jyotindra Jain, Hand-Woven Fabrics of India.

Dheer V.P. (State Editor), Sudarshan Kumar and B Raj Bajaj (Editor), The Gazetteer of India Karnal District Gazeetter, 1976

District and State Gazetteer of Undivided Punjab, Vol. IV, Karnal District, 1918

Gillow, John & Bryan Sentanz, World Textiles

Mukherjee, T. N., Art Manufacturers of India

Nisbet, H., Grammar of Textile Designs

Panipat District Action Plan, 1997-2003 (District Industrial Centre).

Powell, Baden, Punjab Manufacturers

Saraswati, S.K., Indian Textiles

Sundrayial, Khemraj, Panipat Khes

Watson, J. Forbes, The Textile Manufacturers and the Costume of the People

Watt, George, Indian Art at Delhi

3.3. Libraries

Development Commission (Handicrafts), New Delhi

National Archives, New Delhi

National Museum, New Delhi

Crafts Museum, New Delhi

IGNCA, New Delhi

JNU, New Delhi

Askari, Nasreen & Liz Arthur, Uncut Cloth

Banerjee, N. N., Weaving Mechanism

Bhatt, S C., District Gazetters of India, 1997

Dhamija, Jasleen & Jyotindra Jain, Hand-Woven Fabrics of India.

Dheer V.P. (State Editor), Sudarshan Kumar and B Raj Bajaj (Editor), The Gazetteer of India Karnal District Gazeetter, 1976

District and State Gazetteer of Undivided Punjab, Vol. IV, Karnal District, 1918

Gillow, John & Bryan Sentanz, World Textiles

Mukherjee, T. N., Art Manufacturers of India

Nisbet, H., Grammar of Textile Designs

Panipat District Action Plan, 1997-2003 (District Industrial Centre).

Powell, Baden, Punjab Manufacturers

Saraswati, S.K., Indian Textiles

Sundrayial, Khemraj, Panipat Khes

Watson, J. Forbes, The Textile Manufacturers and the Costume of the People

Watt, George, Indian Art at Delhi

3.3. Libraries

Development Commission (Handicrafts), New Delhi

National Archives, New Delhi

National Museum, New Delhi

Crafts Museum, New Delhi

IGNCA, New Delhi

JNU, New Delhi

- aath - eight

- achar - pickle

- baafi - name of a khes

- bazaar - market

- bulbul - nightingale

- char/chau - four

- chandana - moonlight

- charkha - spinning Wheel

- chashm - eye

- chindi - fragment, small piece

- do - two

- durree - carpet, floor covering

- ek - one

- gadra - name of a Khes

- gaanth - bundle, sack

- Hindi - Indian language

- jaat - caste

- Kabir panthis - followers of Kabir

- khana - partition, compartment

- khes - wrap, shawl

- lachhi - hank

- Mahabharata - Great epic war between the Pandavas and Kurus, described in epic tale of the same name

- Marathas - warrior cast from Maharashtra, India

- Musalman - Mohammedan, Muslim

- Sikh - followers of Sikhism

- pachranga - five-coloured

- paira - from pair (leg), foot

- prasthas - a journey, setting out

- pucca - Bitumen road

- Punjabi - People belonging to Punjab, India

- sada - plain, simple

- sutti - from sut (cotton yarn), strands

- tahi - folded

- tehsil - revenue office

- zamidaar - landholder

Research and Writing by Meghna Jain

PANIYAN TRIBE OF NILGIRIS, TAMIL NADUAny inquiry into Indian culture is definitely incomplete without a study of the country’s tribal communities. India boasts of the largest concentration of tribal population in the world, with tribal communities constituting 8.2% of India’s population. Tribal groups in India are characterized by a distinctive culture, exhibit primitive traits and usually live in geographical isolation in the hilly and forested areas. Their unique way of life is revealed in various ways – their appearance, language, attire, ornaments, habitat, food habits and belief systems. Tribal communities across India are at different stages of economic and social development. While some have adopted mainstream ways of living, others are still in transition and some others are yet to step away from their time-honored lifestyle. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs recognizes 75 tribal groups as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PTGs), due to their pre-agricultural level of technology, stagnant population, low level of literacy and subsistence level of economy. The Paniyan tribes, identified as PTG in Tamil Nadu, are a small population of 5541 individuals. They are distributed mainly in Gudalur and Pandalur districts of the state. |

| Appearance & Language The Paniyans resemble African Negroes in their features – short, dark-skinned, broad noses, wavy or curly hair and thick lips. There are many speculations regarding the lineage of the tribe. Popular legend traces their ancestry to survivors wrecked on the ‘Malabar Coast’. However, their origin is still debatable.The men’s dress typically consists of a waist-cloth (‘mundu’). The women also usually wear single-cloth attire, thrown over their shoulder and knotted across the breast. Women wear ear rings, nose rings and colored beads around their neck. Their ornaments are usually made of base metal. Their ear ornaments are rolled palm leaves, fitted in their dilated ear lobes. This unique ear adornment is made at home by the women and is a skill passed on between generations.The Paniyans speak a dialect of Malayalam, with a mixture of Tamil, Kannada and Tulu words. They are socially isolated and usually shy to talk to strangers. |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Habitat Paniyan settlements are usually built at an elevation of 3000 to 4500 ft., and located amidst tea plantations or close to the fields where they work. Their huts are made of bamboo wattle, plastered with mud and thatched with grass. Dwelling in hilly areas, Paniyans run the risk of their settlements being destroyed by wild animals. Attacks by groups of wild elephants are common, and Paniyans need to be prepared for such exigencies.Recently, most Paniyans have moved to government-built modern houses. These houses are single-roomed. Cooking is typically done outside the home. |

| Economy & Social Organization The word ‘Paniyan’ originated from the Malayalam word ‘Panikkar’ (meaning labourer), and agricultural labor was the original occupation of this tribe. Paniyans earned their livelihood by working in fields and on estates of the Chetti landowners. The Paniyans were earlier famous for hunting tigers and panthers. They usually do not have landed assets. Older studies on the tribes of the Malabar describe Paniyans as “agrestic slaves, bought and sold with the land, to which they were attached as slave labourers.”They are now freed from bonded labor. However, they do not have permanent employment and engage in seasonal casual labor. This added to their economic backwardness, and forced them to look for secondary sources of income. This has also led to women participating in economic activity. Apart from agricultural labor, Paniyans engage in the collection and sale of fuel wood to coal depots and self-cultivation of spices (chiefly pepper).Paniyans follow community-level endogamy i.e. a Paniyan marries within one’s own community. To regulate this system, they have matrilineal descent groups called ‘illam’. However, Paniyans today do not remember their illam. Monogamy is the most common form of marriage found among the Paniyans. |  |

|

|

Food Habits Rice is the staple diet of the Paniyans. Paniyans are non-vegetarians and relish fish, crab and prawns in their meal. They smoke cigarettes and chew tobacco regularly. |

| Belief System Paniyans believe in ancestral and supernatural beings, and identify them with the physical environment. The Paniyan temple consists of layers of stones at the foot of the sacred tree. These stones represent images of the spirits.‘Kuliyan’ or ‘Kulikan’, the soul of a Paniyan legendary hero is worshipped for prosperity in their agricultural work. ‘Velliyam’, the female soul is revered for fertility and welfare of the children.Paniyans also worship ‘Kattu Bagavathy’, the goddess of the woods. Due to close proximity to Hindu societies, and also to suit their landlords, Paniyans believe themselves to be Hindu. Today, Paniyans worship various forms of Hindu deities like Mariamman and Kaliamman. |  |