JOURNAL ARCHIVE

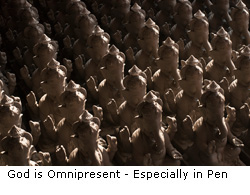

God is Omnipresent. Quite literally in Pen.

Everywhere you look in the quiet by-lanes of Pen, you see idols of the Hindu God of Luck and Prosperity, Ganesha, in various stages of production. Watching you from the parapets of houses while waiting for the the paint to dry; peeping through the windows, while the artisans provide finishing touches; and of course, establishing their presence in full glory atop the many small trucks which are transporting them, in various shapes, sizes and colors, to all parts of Maharashtra, and even to places as far as half way around the world to the US.

What culminates as 11 days of festivities, seen at its most pronounced form usually in Hindi movies, and felt at its most sublime form at Chowpatty in Mumbai every year, actually begins here

as soon as the festivities finish. Lives of more than 30,000 Indians in Pen are centered, directly or indirectly, around the creation of the idols. What culminates as 11 days of festivities, seen at its most pronounced form usually in Hindi movies, and felt at its most sublime form at Chowpatty in Mumbai every year, actually begins here

as soon as the festivities finish. Lives of more than 30,000 Indians in Pen are centered, directly or indirectly, around the creation of the idols. While the karkhana/ workshops exist aplenty, and one does get a feeling of industrialization due to the mass production through earthen casts, the process in its entirety is still largely a form of art. From the selection of pose, size and color of Ganesha, to accompanists, fragrances and time taken to make different idols, everything has a very human element in it, something that machines will find very hard to emulate.

Anything to do with Ganesha can, simply, not be taken lightly. For, he is the Lord of Good Luck. All Indian Gods have a charming physique and yet chequered mythology. And here is a God, pictured as pot-bellied, with a twisted trunk and mouse as the official vehicle, yet the first to be worshiped and never spoken grey of in any mythological literature.

Ganesh is the most unusual God in Indian mythology, and Pen is most unusual place for it to be the hub of Ganesha industry because no raw material is produced locally, and there is no long-tanding tradition of art in Pen. The clay used to come from distant places in Gujarat and the colors were bought from the market. I wonder if this is irony, or a rather fitting meeting of odd friends.

While the karkhana/ workshops exist aplenty, and one does get a feeling of industrialization due to the mass production through earthen casts, the process in its entirety is still largely a form of art. From the selection of pose, size and color of Ganesha, to accompanists, fragrances and time taken to make different idols, everything has a very human element in it, something that machines will find very hard to emulate.

Anything to do with Ganesha can, simply, not be taken lightly. For, he is the Lord of Good Luck. All Indian Gods have a charming physique and yet chequered mythology. And here is a God, pictured as pot-bellied, with a twisted trunk and mouse as the official vehicle, yet the first to be worshiped and never spoken grey of in any mythological literature.

Ganesh is the most unusual God in Indian mythology, and Pen is most unusual place for it to be the hub of Ganesha industry because no raw material is produced locally, and there is no long-tanding tradition of art in Pen. The clay used to come from distant places in Gujarat and the colors were bought from the market. I wonder if this is irony, or a rather fitting meeting of odd friends. Beginning 1970, the opening up of transport options from Pen to Mumbai and Pune gave the place a strategic locational advantage and turned this nascent art into a booming business.

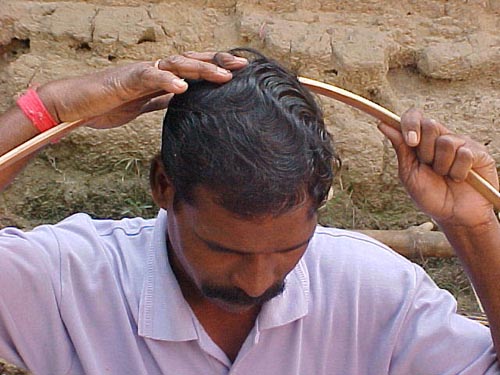

The artisans of Pen seem to firmly believe in the "Work is worship" dictat and have given it a different dimension by adding, "worship is work." Looking at the artisans go about their day with the concentration only a devout believer can portray, is transcendental in its own way. However, things have changed with time. Yet, the more things change, the more they remain the same. The process remains the same; the output looks a little different.

Beginning 1970, the opening up of transport options from Pen to Mumbai and Pune gave the place a strategic locational advantage and turned this nascent art into a booming business.

The artisans of Pen seem to firmly believe in the "Work is worship" dictat and have given it a different dimension by adding, "worship is work." Looking at the artisans go about their day with the concentration only a devout believer can portray, is transcendental in its own way. However, things have changed with time. Yet, the more things change, the more they remain the same. The process remains the same; the output looks a little different.  The God remains the same, worship is now more a festival. So while earlier, it was all about one design, but different sizes, it is now about adding fluorescence, modern crack resistant material like zinc oxide and sittings beyond the traditional "one-handed blessing" Ganesha. All in the lively spirit of festivities.

God created man. Pen is one of the few places where God accepts to be created by Man.

Acknowledgement: Mr. Shrikant Deodhar (Kalpana Kala Mandir, Pen) The God remains the same, worship is now more a festival. So while earlier, it was all about one design, but different sizes, it is now about adding fluorescence, modern crack resistant material like zinc oxide and sittings beyond the traditional "one-handed blessing" Ganesha. All in the lively spirit of festivities.

God created man. Pen is one of the few places where God accepts to be created by Man.

Acknowledgement: Mr. Shrikant Deodhar (Kalpana Kala Mandir, Pen) |

‘India’ and ‘international’: terms redolent with implications of tradition, modernity, identity, change, promise and challenge. The generation that participated in achieving Freedom, including the founders of the India International Centre, were confident that India had a message about the meaning of a democratic, syncretic society as well as what resurgent India could represent to the world outside. The Centre was intended as a space within which dialogue could enhance an understanding of diversity and tolerance, help develop capacities for managing difference, and assist measurements of progress relevant to a just society. Through the years, IIC has served this mission admirably. Yet recent events remind us that as a nation, managing difference and diversity is perhaps a greater challenge today than it was in 1947. IIC often appears as island of sanity surrounded by troubled waters, and a new generation cannot take for granted the concepts that brought the Centre into existence. They have come of age during years that have challenged the qualities and assumptions on which free India was founded. Additionally, they must deal with major new challenges: the degradation of our environment, the rise of terror, the impatience of communities left for too long at the margins of society, the impact of transforming technologies, the rush to convert citizens into consumers, and a pace of change that is entirely new to experience. The young are thus being challenged to re-discover their heritage, and to re-state the postulates on which India can move into its future. While unparalleled opportunities await them, youth seems caught between a society that lurches between alternative identities and histories of ‘India’ and the pressures that threaten their nation and planet. Within such chaos, can IIC be a catalyst for an Indian identity and an Indian confidence? Loss and Opportunity There are political, social, cultural, environmental and indeed spiritual dimensions to this quest that cannot be captured in a brief note. Amidst hope for alternatives free of ideological baggage, there is concern over values lost to cynicism and corruption. Alarming signs cannot be ignored. The abysmal state of Indian education inhibits turning classrooms and universities into spaces within which each generation rediscovers India. The implications are still with us of a masjid destroyed seventeen years ago and of pogroms conducted to establish majority dominance in 1984 and again in 2002. A great artist, his paintings celebrated at IIC, lives in exile. A great play performed at IIC is banned, even as its author’s passing is the loss of a national treasure. The largest sector of the economy after agriculture --- hand production, employing uncounted millions --- is confined to the margins as a ‘sunset’ activity irrelevant to super-power aspirations. Media promotes every conceivable notion of modernity (from western fashion to skin colour) that can degrade an Indian sense of self-worth. We remain unable to feed, clothe or house our citizens in anything approaching dignity while an expanding middle-class races toward waste and greed. A pattern of consumption is being thrust upon us that threatens everything we know about protecting the planet we will leave to our children. Millions suffer and die without sanitation, even as Gandhiji made this the foundation for true freedom more than a century ago. When IIC was founded, India could boost of a cadre of great Indian scholars. Today this class has diminished to the point of extinction, and India has begun to depend on foreigners to interpret its past. What does that portend for the future of an ‘India International Centre’ in which scholarship is accepted as the enduring foundation for understanding and peace? Surely we cannot continue to drift in this manner, afraid and incapable of taking greater charge of a “tryst with destiny”. Despite the gloom, there are forces that can support and lift a contemporary search for quality. History justifies the Indian experiment, and the global relevance of India’s commitment to managing diversity within democratic frameworks. The environmental movement has brought to the fore concepts of development that were first articulated in India’s struggle for freedom: sustainability understood as justice and as a balance between nature and human society. The understanding of progress has finally moved beyond measurements of production and income to indicators of human development that can track movement toward justice, security and identity within change --- just as Gandhiji had urged. Global movements to empower the marginalized and to protect the planet have supported and often been inspired by Indian example. The ‘idea of India’ has taken a universal relevance. “A discipline of Modernization” Thirty years ago Romesh Thapar, one of IIC’s founding spirits, examined the challenge of an Indian identity within the processes of modernization. He insisted that “the attempt to interpret modernisation in one stereotype model must be defeated”. He warned that “vulgarity, in all its frustrations, its duplicity and imitation” has “the propensity to return with redoubled fury. It returns on the basis of the slogan that variety is the spice of life. It returns by dressing bad taste in modernization, making it fashionable and competitive. It returns by surreptitiously entering other areas of creativity and aesthetic. It returns because of an embedded inferiority complex of people’s rule for long by alien powers…..” Romesh called for the need to “draw upon the great heritage of the world knowledge and experience to create a discipline of modernization which dissolves the division between rich and poor, the contrast between waste and want and the repetitive patterns of ugliness and beauty which constitutes the violated environment of our planet...” Romesh Thapar’s warning of thirty years ago has lost none of its urgency. A “discipline of modernization” is more critical to India’s survival than ever before. It can offer hope and opportunity. Can IIC pay itself and its founders the tribute of reviving a dialogue toward such a goal? I am suggesting a dialogue that reaches out beyond the Centre, appealing to young people in all parts of the country through like-minded institutions, and in as many languages as possible. The Centre can be a space that both initiates dialogue and then draws collective wisdom together, using that wisdom to help transform our nation and to inform IIC’s own agenda for the years ahead.

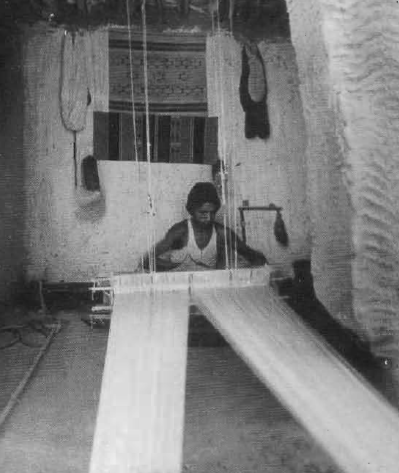

The Deccan Herald of Bengaluru last month published an excellent article by Geetha Rao on the Ilkal saree, which reminded me of my visit to that legendary weaving center in March 2001. Here are my notes of the visit: The Guleds of Ilkal are textile merchants. Phaniraj Konappa Guled’s father was Konappa Guled, and his father was Chandappa, son of Rajappa. Chandappa began working, while he was still a teenager, as a gumastha [clerk] in a saree business, and then went on to set up his own business at the age of 50 in 1875. Phaniraj, today, is about 60 years old. The next generation continues in the business: Phaniraj’s son Vijay Kumar and his brother’s son Praveen. Praveen has a degree in Textile technology from a Raichur college. The Guleds belong to the Swakula Sali jati. The product they deal in is just one, the Ilkal saree, characterized by its indigo dyed cotton yarn and its distinctive design of a plain, striped or checked body, the indigo cotton in both warp and weft being alternated with silk or with ‘chamka’, art silk [rayon]. At its peak, which Phaniraj reckons to have been in the 1950s, the family business was running a hundred looms and producing and selling about a thousand sarees a month, mostly to the Maharashtra market, but also to Gujarat. Even today there is a demand from these markets: just the other day someone came from Kutch looking for these sarees. In keeping with Maharashtrian and local tradition, most of the sarees are 7 metres long. On the streets of Ilkal about one in ten women that I see, all from the working class, are wearing the Ilkal saree, a few with khand cholis. Today the Guleds sell 300-400 sarees a month. The Guleds were different from most of the other entrepreneurs in the region in that they dyed the yarn, ran their own looms, and marketed the end product themselves. By controlling all the aspects, they were able to maintain the quality of each, and thus became the most respected as well as the largest merchants in Ilkal. The more common arrangement was for the entrepreneur to have the yarn dyed by an independent dyehouse, and then have it woven on his own looms. “What a business it was”, Phaniraj reminisces, “good weavers, good wages, good sarees, a good business and good returns!” The Guleds live in a spacious and well-ordered stone house with teak rafters, cornices, and columns, built on those ‘good returns’. They could not afford to build such a house today. Nor could R B Gottur, the dyer, nor on a much more modest scale the Muslim Patels, ex-weavers now following such trades as paan-shopkeeping and taxi driving. It was the thriving textile trade of the region on which they all prospered. The Patels’ houses, small though they are, are built of stone, and are their own. These are now being lost because of increase in debts. The main occupation in the villages around Ilkal: Ameengarh, Sillibari, Dotihara, Kamathgi, was indigo dyeing and weaving, with perhaps 400-500 looms in each village, and 5,000 in Ilkal town itself, making a total of around 10,000. It is Vijay Kumar’s opinion that even today there are the same number of looms, or even more, in Ilkal, though in the villages around, it has sharply declined. The new factor in the last five years is the emergence of the powerloom: according to Vijay there are 3,000 in Ilkal town, all weaving the Ilkal saree. In Guledgudd alone khand [brocade used for the choli blouse that is worn with the saree]is woven along with the indigo vat dyeing which is still practiced using German ‘indigo’. There were upto the 1970s some 3,000 looms weaving khand in Guledgudd, according to Phaniraj. For the dyeing the Guleds had a separate house, with 38 indigo pots, each 4’ deep. They used to dye the yarn, enough not only for the looms which they themselves ran, but also to be given out to the weavers in the villages around. The process of indigo vat dyeing began with the breaking up of the indigo cake into bits. The cake comes from Tamil Nadu, from Udayar, and the one they showed me was the usual heavy, adulterated indigo that the Tamil Nadu suppliers in recent years have been supplying. The bits are then soaked with chunam-water and sudda-matti water, warmed, and stone-ground. The appropriate quantity is then measured out into the pot, with more of the water, and left to ferment for 3-4 days. This stage, of vat preparation, is the most skilled part of the whole exercise, and needs years of experience to tell how much of each ingredient is to be added, how to correct the vat if it goes wrong, how to renew a running vat, when the vat is to be completely re-started, etc. Dregs of used vats are used to start new ones. The yarn is prepared by washing, and by soaking in an emulsion of soap-oil & water for a day, and then dipped into the pots, a dip a day, drying out in the sun in between each, upto 7-10 dips. The deep black of the Chandrakali needs 14-15 dips. German indigo replaced the natural product in the 70s, but that didn’t last long. The decline of indigo dyeing began at the same time. Why did the sarees we had got from them in Chandramouli’s time, about 1994, have white patches? And why were we having the same problem with our vat dyeing in Chinnur? “White patches come either from not loosening the tie of the hank enough, or from omitting the soap oil treatment”, says Guled.

Each design of the Ilkal saree has a name:

Rasta – fine warp lines

Double rasta – as above, double

Jhabra[zebra] – wider stripes

Popadi rik – squares in fine double lines with a different colour between them

Dhapda – a bolder version of the above

Kondichikki – fine checks

Chandrakali – indigo black body, the most prized of all Why indigo? I wondered if there was some ritual significance to it, but was told that it was because “women from all walks of life liked it”. An Ilkal saree was a valued possession, conferring status on the wearer. Richer ladies collected the silk version, and working women the cotton & chamka. The local kasuti embroidery was done on the black Chandrakali. The border is always red, and usually of silk or chamka, with either zari or thread design, and with a silk or art silk pallav. The pallav is always of the traditional design. Within these boundaries there are several permutations and combinations of colour, design and of the three materials, producing a pleasing variety. The Guleds have a rich collection of samples, collected over generations. The earlier ones are of course of indigo dyed cotton, mixed with silk, or of silk alone, some with zari. Some of the borders even in the sarees that are of chamka and cotton have silk pallavs in both warp & weft, entailing a costly attaching process. The border which is now in vogue is ‘pharas petti’ or ‘chikki pharas petti’, a narrower version and ‘godu pharas’. Before that was ‘Gomi’, and earlier ‘rui phool.’ The red border of the saree was originally dyed with a vegetable colour made from ‘piste ka phool’ and haldi, made into a paste, a process which took upto 8 days, according to the senior Guled. The material was imported from abroad, and was replaced in the 1950s by ‘kirminj’, a crimson acid dye from the factories of Geigy, ICI and others, sold through an agent from Bombay. “Ghadial [clock] chaap ‘Kirminj’ came in 50 kilo packs, and needed 2 days’ soaking,” says R B Gottur, of Hospet galli, Banikatti road, who still runs a dyehouse. Since the 1970s the acid dyes too have been replaced by naphthol dyes. “We had to stop indigo dyeing for only one reason,” says Phaniraj “and that was that the workers refused to do the hard work that indigo dyeing takes any more, even for good wages, they were just not prepared to work” The Guleds gave up indigo dyeing in the mid nineties. “Even one of the naphthol dyers quit yesterday”, complains Vijay Kumar. “It was hard work” confirms Gottur, “and the dyers used to get TB”. Gottur is not from a traditional dyeing family, but took it up when he was thirty, thirty years ago. “Pitambarsa Katwa, Vitthalsa Chauhan were traditional kshatriya dyers, now they are all dead and their children are running soda shops” I’m told, in Gottur’s dyehouse. Here chamka is dyed in vivid naphthol colours. On my way to the old town I cross a bridge over a dried-up stream bed strewn with discarded plastic. This is what remains of the Hirehalla stream. “The water of Hirehalla nala of Ilkal was what gave our indigo dyeing its sheen” says Phaniraj. “Fluoride,” adds Vijay Kumar,“it had a high fluoride content”. Now the stream is dry. It has been dammed upstream at Balkundi, sometime in the early 1970s. “The government’s policies are all wrong” says Guled senior, shaking his head. Debbie Tyagarajan of Dakshinachitra has been in touch with them, they have set up a loom for her at the Crafts Village in Chennai. She has invited them to take part in exhibitions there, from which they have had good sales. Dastkar used to invite them for exhibitions too, but hasn’t for a long time. The Spanish couple who stayed for 3 days and learnt the process from them does not reply to their post-cards, and when Guled visited them in Pondichery, they did not let them see the vat. They often get requests to explain the process of indigo dyeing, in fact a letter announcing the arrival of someone who wanted to set up her own vat arrived while I was there. But there is little done for them in return.By Design: Sustaining Culture in Local Environments

Issue #004, Winter, 2020 ISSN: 2581- 9410

Many of the contributors to this collection of essays have highlighted the positive results of the efforts made in India since Independence to sustain traditional crafts and textiles. Abduljabbar Khatri and his son, Adam, for example, have expressed this most eloquently in their essay. But as I reflect on the business of craft and craft practice in today’s context, the tenor of my essay is cautionary. Injecting a note of prudence in this short piece, I focus on just four issues that may pose a threat to how the crafts are managed and sustained as they negotiate globalization, urbanization and an enhanced modernity in the years to come. 1 The Paradox of the Digital India has leapfrogged into the digital world like duck to water. As of January 2019, the country had over 560 million internet users, a figure that is projected to grow to over 660 million users by 2023. Second only to China, its current internet footprint covers up to eighteen thousand cities and over two hundred thousand villages. The power of the internet is increasingly reflected in new possibilities and greater opportunities on offer for communication, for business and the speeded-up transmission of ideas; it is unsurprising then that this is shaping and shifting traditional craft practice. Craftspeople are googling, carrying on business conversations, accessing new markets and materials, receiving designs, sending photographs and fulfilling orders online. While few craftspeople manage their own websites, large numbers have Facebook pages. However, the number of commercial online sites selling craft products has proliferated, opening up new channels of sale and often generating entirely new customer bases - all of which increases the digital footprint of their crafts. Online dissemination of information on crafts and its practitioners has also played a key role; one such effort is Asia InCH, the online encyclopedia of traditional craftsmanship in South Asia that is the initiative of the Craft Revival Trust (CRT), the organization with which I work (and founded in 1999). Asia InCH has information on over two thousand one hundred living and endangered crafts and their practitioners in the eight countries of region - India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Maldives, Laos, Sri Lanka. With mobile subscriptions in India topping 87% per 100 inhabitants further seismic shifts can be expected as plans for even more affordable smart phones are being rolled out. Ranked as having the lowest mobile data rates in the world (US$ 0.26 for 1 GB) we can expect far greater change as many more Indians come online. And therein lies the paradox; while there is an all-round delight with speeded-up communication, the other side of the coin is the disruptive force of digital technologies on the handmade – a threat perhaps equal to, or greater than that encountered at the time of the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth century when the great transition from hand production to new machine manufacturing processes took place which led to the proliferation of factories and the advent of mass production. Digital technologies are the disruptive phenomenon of our times. A double-edged sword, we cannot do without them anymore and yet, as we speak, new technologies are being developed to transfer and to reproduce with unimaginable accuracy and at lightning fast speeds: 3D printing is already old hat. The shifting digital sands are likely to bring in increasingly fundamental social and economic change in the way that we produce and consume. The question that faces us today, therefore, is what the effect of these juxtapositions between the traditional handcrafts and ever mushrooming digital developments will lead to? If I were to extrapolate into the future based on evidence from the present, two broad scenarios seem to be emerging: the first that excellence in crafts will continue to rule. Time taken to slow-produce handicrafts with minute attention to detail will continue to have a great cachet and the demand for bespoke, customisation heritage products will continue to excite attention in the future. On the other hand, the situation that we already face – that of copying and faking - will only escalate. 2 Copying and Faking Leading on from the digital is the age-old issue of replicated and fake craft products – now made more urgent. The stories are endless from power-loom copies of hand loom, resin casts duplicating wood carvings, digital and silk-screen prints of embroideries, of appliqués, of shawls and of weaves; transfers of tribal and folk art, lost wax metal figures made in molds, and the many other instances that are replicated in thousands and marketed as handcrafted, hand-woven and traditional at far lower prices than the original. Copying is a profitable business for many. This freely available cornucopia of heritage goods requires no investment in product development. Furthermore, the instant recognition and ageless appeal of these products and designs that are replete with cultural and symbolic value offers a ready market. This replication with no fear of reprisal thus makes for a win-win business model! For craftspeople and their communities who are at the receiving end of this free-riding it has led to a huge economic loss of income and livelihood - a loss that can and does threatened hand-production. This has clearly emerged in the NCAER Hand loom Census 2009-10 where over 33% of the weaver households interviewed felt that the greatest threat to their livelihoods was from the mill and power loom sector. This is further compounded by craftspeople’s feelings of marginalization and helplessness because of their inability to prevent or effectively deal with this copying and faking. It is equally a loss of the collective knowledge of their forefathers. . Stakeholders, craft communities and others no longer have the luxury of time to deal with these issues as we are now faced with a digital present in which these cases of copying and ‘passing off’ will only multiply. To illustrate the point, several images have been included in this essay that readers will recognize as some of the iconic crafts and weaves that have been replicated by machine processes but are passed off as handmade. In common with many other countries, India too has some legal recourse. The Geographical Indications of Goods Act (G.I. Act), a sui generis intellectual property right legislation was notified in 2003. This Act is applicable to products which corresponds to a specific geographical location or origin be it a village, town, region, or country. The use of a Geographical Indications Act as a certification that the product possesses certain qualities, is made according to traditional methods, or enjoys a certain reputation, due to its geographical origin. Often associated with agricultural and food products (Champagne, Basmati Rice, Mizo Chilli, Alphonso Mango, Darjeeling Tea, etc.) its extended protection includes products of traditional knowledge that are associated with or deriving from local cultural traditions. In the case of craft (and others) the Act protects the moral right and intellectual property of communities and the potential economic benefit arising from their creation. Of the 343 G.I.’s that have been granted to date in India a little over 60% of the total are in the area of heritage arts, crafts and textiles. A noteworthy number as IPR protection is being taken seriously by craft communities and as part of government policy. The G.I. Act is historic as for the first time in India it provides a means of protecting the trade-related intellectual property of communities as a public collective right as it confers exclusive legal right to the holders of that particular G.I. to produce and market the G.I. goods. Once a G.I. is registered it forms the basis for ownership and production and sale by anyone other than the producers concerned can form the basis for initiating action, thus curbing fakes as well as the entry of spurious goods into the market by others. I would go as far as to say that this Act has started the process of leveling the playing field for the creative producer community of traditional handicrafts, folk and tribal arts and the weavers, among the others it covers. However, more than sixteen years after the enactment of the Act we are confronted with many challenges. The first among these is a paradox; the registration of G.I.’s is developing apace yet no handicraft G.I. has been used as a powerful tool and a marketing opportunity: why? Iconic heritage crafts associations have not taken the next logical step after registration to benefit from the provisions of the Act to brand and market under their own powerful logo – a right conferred on them alone. Additionally, why have none of the registered handicraft G.I.’s used the law to proceed with legal action against counterfeiters infringing the Act? There has not been a single case to date. This under-utilisation of a powerful legal instrument is an indication of opportunities lost, rather than of competitive advantages gained. We need to close this G.I. gap, to acknowledge that heritage crafts are valuable business assets and prized brands and enforce the legislation. 3 Dealing with success: regulations and compliance In the past many of the traditional crafts were largely produced by extended families, within tight-knit patterns of professional kinship in which business and production was arranged. With craft production now increasing year-on-year, workshops and karkhanas (ateliers) are expanding and the old order is changing. In the rising production and export graph the share of hand loom in total cloth produced in the country has increase from 11.82% in 2015-16 to 12.61% in 2016-17. Export statistics of handicrafts too reflect a per annum increase of 10.8%. On the ground in Bagh, Madhya Pradesh, for example, Ibrahim Khatri, master block printer, states in his latest CV that he employees 4500 people to fulfil the many orders he receives from urban customers. With success comes greater scrutiny and like Caesar’s wife, heritage craft businesses need to be beyond reproach. The business of craft is required - like other businesses - to follow the law of the land. The Factories Act of 1948 applies to any workshop or karkhana that has 10 or more artisans. A plethora of other laws and Acts are also obligatory, including: Contract Labour Law (1970); Apprentice Act (1961); Child Labour Act (1986); Employees’ Provident Fund Act (1952); Minimum Wage Act (1948); Air Emission and Control of Pollution Rule (1982); Chemical Management (15 Acts and 19 rules have been laid down) ; Water Prevention and Control of Pollution Act (1974); Environment Protection Act (1986); and so on, and so on. While we talk of the ‘zero carbon footprint’ and the ecological- and environmentally friendly nature of the crafts, we will sooner rather than later have to back up these claims with on-the-ground proof supported by facts and figures. This is not helped by newspaper reports, field research and anecdotal evidence which reveal widespread water pollution, dismal work conditions, use of toxic chemical and dyes and in addition, below minimum level pay. For instance, the exploitative daily wages of weavers in Bodo land, Assam and in the outskirts of Banaras of INR 35-50, sweatshop type conditions, poor lighting and ventilation, lack of sanitation, are only some of the problems on a long-list. As large retailers themselves come under scrutiny to sell and source ethically, the onus will fall on them, as well as non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and master crafts persons and weavers, to ensure that norms are followed. Regulation will range from the use of responsibly-sourced raw material, pollution and environment standards to work conditions, better ergonomics, and fire and safety issues. Adherence to child labour laws, minimum wages, and basic human rights, etc, will, likewise, become essential. It is only a matter of time before heritage crafts producers will need to fulfill these basic expectations. In addition, with increasing interest overseas in heritage craft products, the need to comply with international codes of business will soon be the norm – or orders will dry up – as these are the necessary prerequisites that importers will demand. Regulatory compliance and standards are an essential part of an ethically-driven business approach – thus adherence to them will serve to make the cultural heritage tag more meaningful. 4 Hierarchies of value: formal education v. received knowledge At a seminar titled ‘Craft Nouveau : A decade of education for artisans’, a number of those who had been involved in some way or the other with design education for artisans in India came together. Organised by the Craft Revival Trust it was held in collaboration with Somaiya Kala Vidya (SKV) the artisan design and business management educational initiative in Kachchh district, Gujarat and its founder-director, Judy Frater. (See Ruth Clifford’s essay for discussion of SKV and other initiatives for artisans). The focus of the seminar was to reflect and take stock of the decade of education for crafts persons and to map the road ahead. There were many points of interest to take away but here I address only three that are of particular relevance to the discussion of how cultural heritage is managed and the role of design in sustaining India’s craft traditions. The first is to highlight the amazing vitalization wrought by education on young craftspeople and their transformation into designers and business graduates. themselves, by the SKV faculty and their advisers, as well as by representatives of NGOs, designers, domestic and international marketers and others who had interacted with them. The second point to address is the impact of education on status and power experienced by the SKV graduates, an issue returned to by many of them and the craft patriarchs present like Shyamji Vishramji Siju (master weaver), Dr Ismail M Khatri and Irfan Ahmed Khatri (both master ajrakh printers) and Dayabhai Kudecha (weaver and entrepreneur). While economic success was being achieved by many, without relevant and appropriate education there remained an inequality between their status as craft practitioners and others such as designers and design-entrepreneurs involved in crafts. “New” inputs into their craft were assumed to be exclusively in the ‘others’ domain while they - the craftspeople whose tradition was being explored - were relegated to a biddable, subservient role as labour hired to do a task directed by others. Education gave them back their rights. The third key point to take away from the seminar was the aspirations of these young men and women. Currently the Indian crafts sector is the second largest source of employment after agriculture; the numbers are uncertain but it is estimated that about twenty million craftspeople and weavers continue in twenty-first century India to be educated in skills that are learned through oral transmission and apprenticeships outside the mainstream educational system. There is no policy in place that recognizes and acknowledges this oral learning – now called ‘received knowledge’ – within the formal educational system or, indeed, the employment process. It is common knowledge in India that there is an increasing lack of interest in the younger generation to continue in craft practice; this is due to several reasons, not least among which is the perceived prejudice and inequalities of status experienced by craftspeople. Among the problems they have to contend with is the widespread belief that information garnered from text books is superior to received oral knowledge. The dissociation between these different forms of learning and knowledge has been inimical to us all but especially to the rising generation of crafts persons. The question that arises is - what can we do to fill this huge aspiration gap? It is not only critical that methodologies are developed that contribute to design education frameworks but also that they are sensitive to the sheer complexity of the sector. They need to make a meaningful and sustained contribution that is free from tokenism - taking a leaf from SKV and Kala Raksha Vidyalaya (KRV) in Kachchh, and the Hand loom School in Maheshwar, Madhya Pradesh which also offers design education for artisans. Study of the processes and models adopted in other countries that have realized the value of handicrafts now the number of craftspeople has been decimated may also be of benefit; for instance, Japan supports rigorous training in over two hundred traditional crafts; France awards the title of Master Of Master of Art (‘Maître d’Art’) to those with an exceptional mastery of techniques and know-how who further transmit their skills and knowledge to students who will be able to perpetuate them; Sweden has National Folk Craft institutions; Korea, and now increasingly China, invests heavily in training the next generation of craftspeople that are open to traditional practitioners and their families as well as new entrants There is an urgent need for a move towards greater equity between different types of learning and knowledge, requiring a removal of the barriers in academia, and elsewhere, that are currently weighted against the bearers of traditional knowledge. Similarly, it is imperative that we in India move beyond tokenism and create enduring and substantive change through institutional development, the formation of indigenous technology Conclusion While we in India have experienced the huge effort made by the Government of India (and other organisations) at sustaining traditional crafts and textiles, craft futures continue to present considerable challenges. As a nation we cannot forge ahead unless we push to establish a more equitable, even-handed and inclusive environment for craftspeople to work in. It will require meaningful initiatives and a concerted effort to ensure that this essential part of our cultural fabric is sustained and that these keepers of our traditional knowledge are nurtured, taking their rightful place in the near future. Our future depends on how these issues are tackled - we must build to our advantage and not let our unique cultural heritage be frittered away. List of illustrations laboratories, the endowment of University Chairs to the bearers of traditional knowledge as well as awarding them honorary doctorates in recognition of their expertise. In this collection of essays, we have a contribution by hereditary block printer, Abduljabbar M. Khatri and his son, Adam; Jabbar’s brother, Ismail Khatri, was conferred with an Honorary D. Art by De Montfort University, Leicester, UK in 2003 in recognition of his knowledge and contribution to textiles scholarship. Footnotes https://www.statista.com/statistics/265153/number-of-internet-users-in-the-asia-pacific-region/ Statista : The Statistics Portal. Accessed on 2 March,2019 The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) is a specialized agency of the United Nations. India Profile (Latest data available: 2018) https://cis-india.org/telecom/knowledge-repository-on-internet-access/intnl-telecom-union Accessed 2 March, 2019 Cable : https://www.cable.co.uk/mobiles/worldwide-data-pricing/ Accessed on 2, March 2019. Sethi, Ritu. Deconstructing GI to create value for the handmade. http://www.craftrevival.org/voiceDetails.asp?Code=219. National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER): Handloom Census of India 2009-2010. Table 6.14. Pps 136-137. NCAER, New Delhi. Report on Chikan embroidery of Lucknow :https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/national/lucknows-chikankari-industry-hit-by-cheap-chinese-imports/article8102824.ece Report on weaving in Sualkuch, Bodo weaving and Chennapatna Lacquer toys https://www.thebetterindia.com/69817/handlooms-and-handicrafts-in-india/ Accessed on March 5, 2019. Signatories to the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), administered by the World Trade Organization (WTO) can set in place international legal instruments like the GI to provide the judicial framework of rights and principles with associated policies and procedures to prevent misuse. Introduced in India in 1999. The GI Act was notified on 15th September 2003. Geographical Indications have been in existence, in various countries across the world for several decades GI is defined as “A geographical indication (GI) is a name or sign used on certain products which corresponds to a specific geographical location or origin (e.g. a town, region, or country). The use of a GI may act as a certification that the product possesses certain qualities, is made according to traditional methods, or enjoys a certain reputation, due to its geographical origin”. The GI has been granted to iconic products like Kancheepuram silk, bidri, Madhubani paintings, Molela clay plaques, Kani shawls, phulkari, chikan embroidery as well as to the lesser known Solapur terry towel and the Bhawani jamakkalam. http://ipindiaservices.gov.in/GirPublic/ Accessed on 15 March, 2019. Sethi, Ritu. Deconstructing GI to create value for the handmade. http://www.craftrevival.org/voiceDetails.asp?Code=219. Offences under the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999 are punishable with imprisonment for a term of not less than six months, extendable to three years. Also enforced is a fine – this may not be less than Rs. 50,000 but may extend to Rs.2 lakhs.Cases other than those relating to the traditional crafts on GI tagged products like Darjeeling Tea, Scotch Whiskey and other have been brought to the Law courts. Actual cloth production increased from 7638 million square meters to 8007 million square meters in the same period http://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/AnnualReport2017-18%28English%29.pdf. Ministry of Textiles Annual Report, 2017-18, p.51. Accessed: 30.3.19. An increase of Rs. 31038.52 crores (2015-16) to Rs. 34394.30 (2016-17) http://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/AnnualReport2017-18%28English%29.pdf. Ministry Of Textiles Annul Report 2017-18. Page 200. Accessed : March 30,2019 Also refer to Abduljabbar Khatri and Adam Khtri’s essay (http….). Organised by the Craft Revival Trust at the India International Centre, New Delhi on November 30, 2016. SKV was instituted in 2014. Kala Raksha Vidyalaya, its precursor, setup in 2003, was also founded and directed by Judy Frater. See also: Chatterjee, Ashoke – ‘Kala Raksha and Kala Raksha Vidyalaya’, 11 October 2017. https://asiainch.org/article/kala-raksha-kala-raksha-vidyalaya/ For YouTube link to the seminar, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3AU3FcuzTs Also read: Ashoke Chatterjee: The currency of Dil Bhavana. 11 October 2018 https://asiainch.org/article/the-currency-of-dil-bhavna/ see also: pallasmaa, Juhani (2009), The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture. London: Wiley. Created in 1994 by the French Ministry of Culture to preserve intangible cultural heritage, the title is awarded for life.| We understand that you employ craft techniques and processes in your collections. Which craft techniques have you worked with? I work with a variety of printing and embroideries - block, kantha, kutch embroidery etc. I employ women who have migrated to the city from smaller towns and rural areas. They all have some basic skills with the needle and at my studio they develop these skills to do intricate needlework using beads and creating patchwork patterns. | |

|

You are a NIFT graduate. Were handlooms and traditional textiles included in your formal education at NIFT? I was in NIFT from 1994-97. In our first year we have to undertake the documentation of a craft. I researched the textiles in North Bengal, specifically the Tibetan community settled there. Though I have kept no direct links with them one does imbibe the design and colour sensibilities. I also work with Sasha in Kolkata and have had an association with Dastkar though I do not have a formal interaction with the crafts. I have also begun work with Karam Marg and that might develop. |

| Do you feel that an awareness of traditional hand skills is important for today's designers? Why? Any designer in any country must be aware of their specific cultural context, at the very least. If they don't then they are missing a vocabulary, a language.Do you actually employ craftspeople or do you work through commissions? I employ ten women at the moment. Most of my work is done inhouse. We have flexible working hours, they can take work home if they choose or if the need arises. I do not create in bulk. The work is about accents, details. For instance, in a skirt we might add details just at the end.Do you give them the designs or do you work with the existing traditional repertoire and then modify them within your creations? Though I give them a pattern, design is a symbiotic process where ideas grow while in process. They have an interesting colour sensibility. In the west colour is viewed mathematically, combinations strictly adhere to the codified colour palette. In India colour is more playful, more adventurous. | |

| While incorporating craft skills in your design, do you seek to retain the traditional character of the craft? And how much scope is there to incorporate the spontaneity/ creative instinct of the artisan, even as (s)he molds the skill as per your requirements. Some of the processes are instantly identifiable like embroideries of Kutch or Bengal. But I also innovate. Though I hand print I make my own blocks which have a geometric pattern. So I follow the technique not the design directory. |  |

| What is your experience with craftpersons? Do they deliver on time? Are they open to ideas and suggestions? The first point to remember is that you cannot hurry the craftsperson. They have their own pace at which they work and making it overtly professional would kill their work ethos. Yet on the other hand you have to set deadlines. This interaction requires sensitivity.Is the debate surrounding the ethics of isolating a living cultural tradition and using it as mere embellishment a valid one?It is a valid one. But it is tricky. The dichotomy lies between economics and purity. I have no answers. | |

|

What are your thoughts on the future of crafts in India? There are two kinds or categories of crafts. One is the highly specialized, very expensive which most people are unable to work with as they are hard to commercialise and sell cheaply. They need patrons. The other are easier to incorporate and sustain. |

Kolhapuri chappal look alikes made in rubber and sold by a large shoe chain, Ajrak hand-blocks printed on a roller machine, powerloom masquerading as a Banaras handloom, Kantha printed by silk screen, Dhokra lost wax statues made in moulds that replicate it in thousands…the stories are endless. For many copying is a profitable business. A freely available emporium of ready made goods that require no investment in product development ; goods with an ageless appeal with cultural and symbolic values that add up to a sum that is greater than its parts. The instant recognition and mass appeal of handcrafted products duplicated with mass production technologies churning out replicas at a low cost, with no fear of reprisal, makes for a win-win business model! Craft activists and craft communities no longer have the luxury of time to deal with issues of copying and faking. Faced with increasing consumerism and demand for new products cases of copying will only multiply. For craftspeople and their communities who are at the receiving end of this free-loading it has lead to not only huge economic loss, but even greater to a loss over their ancestral ‘property’ - the collective knowledge of their forefathers. This is further compounded by feelings of marginalisation and helplessness due to their inability to prevent or effectively deal with this copying and faking. We in India now have some recourse to this.

THE PURSUIT OF GI FOR PRODUCTS OF TRADITIONAL CRAFTSMANSHIP

The promulgation of the Geographic Indication Act (GI) of 1999 that came into play in September 2003 has provided some succour under the law as it affords GI holders protection under the law. This GI law protects the GI holder by conferring exclusive right to brand, market and certify the quality and genuineness of the GI goods to the holders of the registration. Production and sale by anyone other than the producers is a punishable offence under the GI Act. A decade after the promulgation of the Act, 155 arts, crafts and handlooms have received a GI status with 17 applications pending. Of the total GI’s registered across India 70% are of handicrafts and handlooms, a noteworthy number, implying that the application for a GI is being taken seriously by the sector. This then begs the question of why no handicraft GI’s have proceeded to use this powerful tool as a marketing opportunity? Why have none of the registered GI’s used the law to proceed with infringement action against cheats and counterfeiters? This is a huge gap, a space on post-GI registration action where joint action by NGO’s and GI holders is now the need of the hour. As pioneers who will have no markers to go on perhaps the first step could start with the adopting of a GI registered craft cluster, working with the community to develop a process methodology that leads to the leveraging of this powerful marketing tool. Developing the GI’s economic potential to help craftsperson’s regain their Rights over their community knowledge, provide guarantees to consumers on the genuineness and quality of the product, create a brand, promote and market it and empower the community. Developing a methodology for others to follow I have attempted to put together some questions on the challenging issues that confront us on the protection that needs to be awarded to products of craftsmanship and additionally to the protection of the traditional knowledge associated with the production of these products. A slow but careful understanding of GI is essential so that we do not rush in where angels fear to tread. Two criterions informed the framing of the questions. The first is the need to keep at the heart of this protection the ultimate well-being of the craftsperson in this rapidly globalised world. The second criterion used was to deliberately take a long view - so that through thoughtful deliberation we can get to the heart of the challenge and create a roadmap that stands us in good stead over the years to come.THE STATE OF PLAY

QUESTION 1: The first and fundamental question is to identify what to protect and why we need to protect it. Some of the reasons why crafts need protection could include:- The protection of crafts and craftsmanship could be to ascribe ownership to communities.

- The protection of crafts and craftsmanship could be to bring equity to essentially unjust and unequal relations.

- The protection could be to accord recognition of craftspeople as holders/authors of the knowledge associated with traditional craftsmanship

- The protection could be to prevent appropriation by controlling piracy, copying, faking and passing off

- The protection could be for Preservation of traditions and culture

- The protection could be for Promotion of crafts and craftsmanship

- The protection could be for Economic benefit

- The protection could be for any other considerations that is valid for craftspeople

- Does the rationale of the GI regime in India serve its objective of protecting the intellectual property of the holders of traditional craftsmanship and their product?

- Does it serve the broader objectives that civil society and other stake holders seek for the sector?

- What, if any, is the recourse of those crafts and craftspeople who are practitioners of the same/similar craft, but fall out of the ambit of the registered GI location?

- Can they apply for additional GI’s?

- We need to study the case of Pochampally Ikat and all the other ikat traditions; study the files on Bandhini and other tie-dye traditions and many other instances where same/similar traditions exist in different geographies.

- Thewa in Pratapgarh, Rajasthan vs. the family that practices it in Madhya Pradesh

- What about those craftspeople who reside outside the the latitude and longitude specified in the GI

- By Government

- By the Holders themselves

WAY FORWARD

Besides working on GI as it is a tool we have in hand we need to take the long view. Once we have defined the different reasons for seeking protection, we need to determine the scope and the extent of protection required to achieve the objective? We need to ask ourselves the question:In an ideal world, what moral bindings, policies, legislations would we like to see in place that is appropriate for the crafts sector given the ethical, economic, environmental and social concerns?

Through the process of consultation with craftspeople, NGO’s and others articulate the requirements and principles that need to be followed for an effective system of protection. Determine the rights and consider the exceptionsThe hesitation I feel when taking up a tough challenge is outweighed by the excitement and intellectual curiosity of being able to explore new ideas to build upon older ones. Therefore, I must thank the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, and Prof Vijaya Ramaswamy, for offering me this opportunity and especially the honour of speaking at the opening of what I am sure will be a fascinating conference. Prof Ramaswamy has devoted a lot of time to the study of Visvakarma. You find her studies referring to the Visvakarma community often described as a unified grouping of five sub-groups - carpenters, blacksmiths, bell metalworkers, goldsmiths and stonemasons - who believe that they are descendants of Viswakarma, through his sons. Manu was said to have worked with iron, Maya in wood, Tvasta in brass, copper and alloys, Silpi in stone and Visvajna who was a goldsmith and jeweller. The kammalars in South India, who claim to be their descendants, are well versed in the shilpa shastras, the art treatises in Sanskrit laying out all the religious and technical processes to be followed in their work to achieve perfect results. Forms and formats were rigid and the process of creating an object was considered a part of a spiritual exercise. The Visvakarma community worships various forms of this deity and follow five Vedas: Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda, Atharvaveda, and Pranava Veda. While these are the specifics, Visvakarma has a grander title. It says in the Rig Veda (10, 81, 7) “Lord of sacred speech, thought swift Viswakarman: the All-maker, let us invoke him to our aid today. May he, the maker of Good Things and giver of great joy, may he gently hear these, our invocations”. He is the god of all architects, engineers and crafts people. He is the supreme architect of the universe, Brahma in another form. He thus provides an overarching umbrella to include everyone involved in the act of work and creative expression. Visvakarma has always held a fascination for me. It began when I saw simple workers from different artisanal professions, shop floors and construction sites pausing work for a day dedicated to his name to clean their machines, tools and instruments and adorning them with flowers. Then they prayed to them since Visvakarma enabled their skills to flourish through them. It seems so fundamental an act, imbued with the utmost respect for one’s own work environment, and recognition that the blessings of a higher being are needed to successfully execute one’s skills at work. Visvakarma is obviously a concept that is depicted as an elderly figure sporting a white beard. It is a concept honouring work and the encouragement of creativity and excellence. So we should see Visvakarma Day, celebrated immediately after Ganesh Chaturthi, as honouring creativity, manual skills and thus the dignity of labour. This day always seemed more important to me than the innumerable holidays accorded to appease different communities and religions in our secular country. To stop work for just a day in order to respect the workplace and the materials that enable the work to happen seems to me a highly sophisticated concept that is only partially matched by the western concept of Labour Day which refers essentially only to the working class in organized environments. Equally importantly, Visvakarma Day brings together artisans and crafts people, mechanics and carpenters, architects and artists of all communities and religions to celebrate their patron and guardian, the architect of the universe. Descendants of the professional artisan castes associated specifically with Visvakarma who today may be involved in wholly unrelated work also take pride in celebrating this day With the belief that all gods displaying different attributes in the Hindu pantheon are ultimately one, and the soul of the One resides in each of us, Visvakarma too can be appropriated by all artisan groups apart from the original five, and indeed, by anyone involved in creative expression. It is from this position that my study of what Visvakarma means to crafts people began. Being an activist in the field, and spending more time in dusty villages and narrow lanes of small and big towns in search of people who uphold India’s craft traditions than in libraries and among books, I found that not only is the ‘progeny’ of Visvakarma spread far and wide, but that crafts people do not need to go to temples to seek him. The true manifestation of ‘work is worship’ is found when one watches crafts persons at work. The silence, the meditative quality of their concentration, the systematic and meaningful application of techniques, the choice of traditional colours, make the final product an offering to a higher being. The earnings from this work are then attributed to this higher being thereby making traditional knowledge and skills, workmanship, spirituality, income, and livelihood part of an integral whole that constitutes a meaningful creative life. This perspective is wholly and satisfyingly Indian. It is this that has cradled and nurtured our crafts inclusive of and beyond castes and religions. We refer to the ‘mapping’ of crafts. I began my quest for the reach and spread of Visvakarma’s progeny and products through the very literal process of creating maps. It began when I saw a map of the markets of Bangkok presented in water colour art by an American artist Nancy Chandler in the early 90s. It struck me that if shopping in such a small country could be presented in this attractive fashion, India offered a multitude of crafts, arts and textiles that should be actually mapped to lead people to them. These maps took on a slow and steady momentum of their own. It took 15 years to complete all the states. Some new states were formed in between and Telangana now will have to be created separate from Andhra Pradesh. Political and geographical evolution repeats the evolution of India’s arts and crafts over millennia as an ever-changing phenomenon responding to the times and needs of the people. At one level these maps were meant as shopping guides, with locations of manufacture and sometimes even some guidance on how to get to a certain village or locality. At another level it had to bring out interesting differences in processes of manufacture depending on local cultures, availability of raw materials and histories. We discovered that in Odisha, women of a certain tribe wore similar blue saris for a festival, while their priestess wore saris specially woven in yellow. Colour becomes spiritually meaningful beyond mere aesthetics. I wanted these maps to be inexpensive and accessible to young students and travelers who cannot afford coffee table books that just look beautiful but serve no great purpose. By coincidence, they came in useful to UNDP and state governments after the Odisha super cyclone and the Gujarat earthquake to easily locate artisan pockets that could be provided relevant relief for crafts people to carry on their traditional vocations. I would like to believe that Visvakarma was ensuring the continuity of their creativity. Coming around full circle, these maps have now been combined with a new freshly expanded text to create the Craft Atlas of India. It was selected by Choice, the premier review journal in the USA which recommends books to colleges and universities all over the country in which they choose around 600 from over 25,000 publications for its excellence of scholarship and presentation. All the maps were done in different art forms of India by artists from the particular state, and every known craft, art and textile was covered. It was nice to know that knowledge about our crafts and their practitioners would reach many students through our initial and very modest attempts at mapping in an artistic way. The Surveyor General of India’s office had to certify all international boundaries of the maps as accurate so there was some scientific accuracy involved within the art work. The major caveat I will add here is that I am fully aware that we could not possibly have discovered all the crafts of India. Some crafts that have been recorded may have since disappeared. Others would have sprung up after the time of documentation and hence remain unrecorded on these maps. But that is the very beauty of the creative craft process of India. It is like a mighty river that forever absorbs new material, throws some away onto its banks, changes course and meanders as it wishes depending on the pulls and pressures of the surrounding environment. Sometimes, like the Varuna and Assi rivers that gave Varanasi its name, crafts dry up and become pathetic and sullied representations of their initial selves. At other times new channels open, providing people with fresh opportunities for creativity and earnings. This is their beauty, and discovering them brings constant excitement. Change too is constant and the search for ever evolving progenies and legacies of Visvakarma continues, like a river, forever. I have come across cultural histories in unintended and interesting ways. Some of you may have heard of a project I did in 2012 called Akshara, Crafting Indian Scripts. It was inspired by my reaction to the constant lack of self-worth expressed by crafts people who felt they were poor and illiterate despite being excellent in craftsmanship. They felt at a disadvantage not knowing English or the computer. They also believed that if their children went to school, craft skills were no longer relevant and yet there were hardly any honourable ‘jobs’ available for many of the literate let alone the semi or neo literate. To persuade them to turn to their linguistic roots, study the scripts of their regional tongues, and apply these through creative calligraphy using their craft skills, we mobilized more than 70 practitioners, in 21 different skills like weaving, embroidery, carving, metal work, ceramics, folk art, and many other forms, using 15 of the 22 official Indian languages. Out of this exploration came over 150 museum-quality objects that opened up a whole new design vocabulary. But this was not all. When I told them to use their own scripts in the form of alphabets, verses, names, phrases, shlokas, songs and local stories deeply embedded in their local cultures a wealth of ideas and cultural histories turned up from this freshly tilled soil. To give you some examples: Bihar’s women do simple forms of embroidery which are being developed into more sophisticated products than mere quilts for a charpai. Applique is one of them. I asked them to create wall hangings based on local stories or festivals and embroider the words of songs in their local dialects. They came out with religious songs sung while standing in the water at Chhat puja and Madhushravani, a festival when a newly married girl first returns to her mother’s home to be seated among flowers. They also brought out a moving old folk song telling of a potter, a farmer and a boatman, lamenting the fact that Sita’s fate would have been very different had she been married into their family where she would have been tended with love and care, rather than meet the unhappy end after marrying into a royal household. The intelligent nuances of challenging existing attitudes of caste, class, and gender set to verse in gentle tones and accompanied by poignant embroidered images are as sophisticated as any brought out by the intellectual community. Likewise traditional artists came up with calligraphy in Kalamkari offering snippets of a song that described a bride’s face adorned with turmeric as yellow as a marigold. In Kashmir kani weaving we created a shawl in the colours of a pigeon. The weaver found a dead pigeon since he could not capture the colours of a live one on his mobile phone. He took it to the dyer who faithfully created yarn in shades of grey with touches of salmon pink since the pigeon’s legs were that colour. A new colour palate came into being. An old folk song welcoming the monsoon in Gujarat when it was advisable to eat karela to ward off malaria, and a hidden welcome to visitors to a home lovingly carved into a wooden door handle were the many forms of communication through craft and calligraphy that came about. Crafts found a new avenue of expression on fresh artefacts and objects of daily use and have since spawned a variety of spin offs that took inspiration from a single idea of how to apply old skills in a new way within a very Indian, very local, perspective. A search for traditional names given by handloom weavers to colours of their saris evoked an era of aesthetic sophistication that would far outshine any Parisian fashion palette or marketing phrase. To express the subtle differences in shades within a similar colour old documents reveal names like kapursafed, camphor white, makkai, creamy corn and subzkishmish, fresh raisins. Old texts describe white further by referring to the colour of white mist, or of steam rising from boiled milk. To neglect, and worse, to ignore such subtle and sophisticated terminology coming from often non-literate weavers and dyers who honour hand work and creativity, and to do this in the face of seasonal colour diktats from the fashion world of the West, is to do disservice to our own heritage that Visvakarma encompasses. Looking at trends in the publishing world, and in government policy-making for the development of crafts, I began to spot a gaping hole that was widening as crafts became more commercialized, imitative and export oriented. To be like the Chinese seemed to be the goal. How can we be like them? We are Indian. We have our own identities and cultural histories from which our crafts are created. It came to me that the Visvakarma’s terrain had no institution of national importance to recognize research, document and add value to crafted objects. Cultural histories and stories add immense economic value to the object. Everyone wants the story behind its maker and its making. I proposed the idea of setting up the Hastkala Akademi on the lines of the Sangeet Natak, Lalit Kala and Sahitya Akademis, but in a new environment free of unwarranted governmental influence, and bureaucratic death traps. Happily the 2014 budget announced its allocation of Rs 30 crore for this purpose with the intention of a public-private partnership model where enlightened patrons would fund but not control the work of the Akademi. It is still in its baby pram - not even taking baby steps yet - but I sincerely hope we can collectively relate the outcomes of conferences such as this to enrich and enlighten such an institution when it begins its work. Every journey into the crafts persons world is one of discovery and wonderment. There must be something that drives these children of Visvakarma to remain true to their traditions and processes of work, never mind how harsh, difficult or tedious they may appear to be. On recent tours to 25 places in India to photo-document different craft, art and textile forms that expressed the meaning of success, for a Google Project for its Art& Culture platform, we found practices motivated by the drive for excellence, marketing opportunities, community demand and support and a love of their own heritage. If anyone visits a tiny village in Chhattisgarh called ……….they will find an indigenous craft form that sprang simply from a woman’s desire to express herself in a world where she found herself isolated. Her eyes roamed over the soil she stood on, the water that flowed nearby, the colours made by leaves and spices in her kitchen. Putting all these to work, her fingers deftly created toys for her child, then a shelf, or a lamp, and finally a wonderland of birds, animals, gods and mortals, leaves and flowers and geometric shapes that became a home that was a museum of her skills. It did not stop there. Her work took her across the world, and inspired others in the village who are today creating similar magical decorations on their walls, windows and doorways . A new art form, close to tradition rather than modernity, was born. In a weaver’s home in Bengal or a terracotta artisan’ hut in Odisha, there will always be a decorated area at the entrance or in the courtyard, where the tulsi plant grows and the evening lamp is lit in prayer. There are no images of gods or goddesses there, but an aura of prayer and the seeking of blessings automatically and wordlessly, are directed towards the god who takes care of artisans. In Bagh, In Madhya Pradesh, printing processes go through 16 stages, with hard labour involved in soaking meters of cloth, drying them, treating the surface, printing in many stages with carved wooden blocks, drying them again, then washing them in a stream of clear water, and drying them yet again. Bell metal workers in Kerala go through many elaborate processes to make lamps that adorn the nearby temple, and ornaments for traditional dancers. These cultures, fostered by the all-pervading spirit of Visvakarma, keeps Indian heritage and culture alive amidst a fast changing world of automation and technology. But here again, the person who uses these work, will pray to it as a tool he needs to use to earn an honest livelihood. To end, I would like to complete the lines of what Prof Viyaya Ramaswamy has quoted at the beginning of her concept note for this conference. They are Ananda K Coomaraswamy’s words on Visvakarma: ....Beauty, rhythm, proportion, idea have an absolute existence in an ideal plane, where all who seek may find. The reality of things exists in the mind, not in the detail of their appearance to the eye. Their inward inspiration upon which the Indian artist is taught to rely, appearing like the still, small, voice of god, that god was conceived of as Visvakarma. He may be thought of as that part of divinity which is conditioned by a special relation to artistic expression: or in another way, as the sum total of consciousness, the group soul of the individual craftsmen of all times and places. Conference on Vishwakarma at Nehru Memorial Centre and Library.