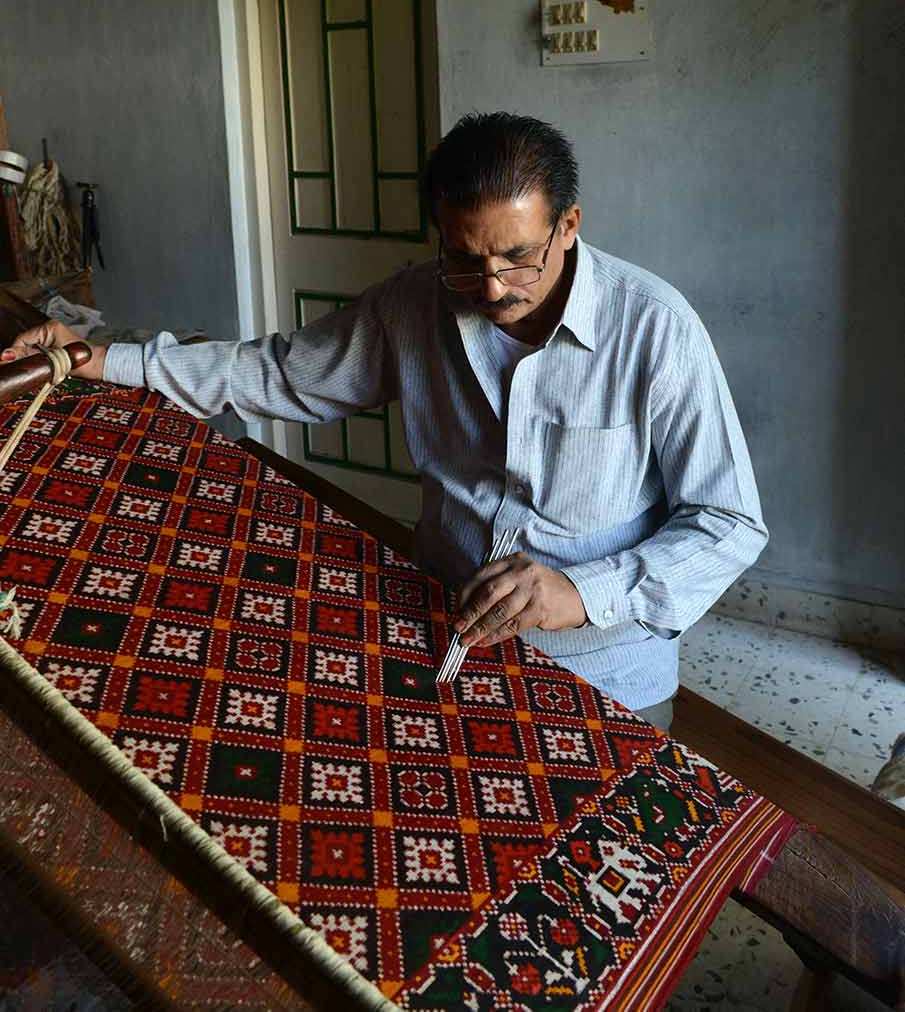

An artisan working on patola sari, Sam Panthaky/AFP[/caption]

An artisan working on patola sari, Sam Panthaky/AFP[/caption]

JOURNAL ARCHIVE

Why The Banarasi Sari Is Special,

Varanasi has had many names beginning with Baranasi in old Pali scripts, and many others like Avimytaka, Suranshana, Ramya and Kashi, before officially becoming Varanasi only in 1956. The city of Varanasi has an unquantifiable aura of being agelessly old, undefinably spiritual, and offering a sense of peace and continuity when you leave the chaos of the city and sit on the steps of any ghat along the banks, getting lost in the stillness of the ever-moving River Ganga. In the same way, possessing a brocade, a tissue or a tanchoi sari woven by a weaver from Varanasi, wearing it on your wedding day, or possessing one, is like having the reassurance of tradition and continuity in a life of full of sartorial changes. The names of different kinds of weaves and designs of the saris too lend a special story to the ‘Banarsi’ sari, as ubiquitous in a trousseau as the Banarsi paan is at a roadside kiosk. Like the multiple names of Varanasi, sari patterns, motifs and techniques like chaudani pallu, jangla, kinkhab, minakari, , konia shikargah, ashrafi , kadwa kairi, badam, ambi, pan buti, gendabuti, t name a few. Even colours have a variety of names, nilambari for the night sky and kapur safed for camphor white. The weave and the name combine to create a magical identity for each sari. I have always linked my love of the Indian textile aesthetic with pride in the skills of traditional weavers and the imperative to ensure the survival of the heritage they carry in their fingers. Unlettered and unsupported, they create beautiful fabrics to adorn priests, popes, monks and monarchs all over the world. Monasteries are decorated with gyasers woven on the looms of Varanasi, and upholsteries in Middle eastern kingdoms are covered in fabrics made of peacock feathers also woven in Varanasi. My future mother-in-law gave me a rich pink silk Banarsi with golden motifs all over, to wear on my engagement day. My mother showed me her old Banarsi. I chose to wear that on my wedding day and not a freshly bought one which I felt was just a waste of money. It was an old rose tissue in which gold and pink silk threads were interwoven, with a pallu and wide borders decorated with pure zari foliage in the jamdani style. The next day, for the reception I had a more elaborate dark pink and gold striped Banarsi that belonged to my great aunt. I felt I carried the weight of my family history. It was already quite old, so while the gold threads (actually real silver dipped in gold) held out, the ageing silk began giving way, parting company from the zari strips which weighed the silk down. Being from Kerala it was more natural to have chosen a rich Kanjeevaram to wear for one’s wedding, but somehow, Banarsis cropped up at each such auspicious occasion and made me feel much more comfortable than if I had worn a stiff newly bought sari that had no story to tell me. In any household that is sari-wearing, where women still hold on to some customary cultural practices involving the use of craft or textiles, which would be at least 70% of India, a Banarsi brocade is bound to have been bought for a special occasion, and treasured till it frays. Even today, elder women pull out their old handloom treasures, offering them to collectors, museums, exhibition curators, their daughters, and even to designers who want to replicate the intricate old weaves, motifs and tasteful colourways. But what about the weavers themselves? There are weavers living at many levels in Varanasi. At the lowest rung are those who earn a pittance when master weavers give them work. The subsist from order to order with no reassurance of regular work, and often desperation sets in. A rung above them come the weavers who are fortunate enough to be kept on by master weavers whether there are enough orders or not, simply because they need an assured work force at hand when orders are received. Production increases between September and March which encompasses the festive and wedding seasons for all communities. For those who do not wear saris, there is the salwar suit, sharara or lehngas to weave. Despite the buzz in large cosmopolitan cities that sari wearing is going down because ‘girls do not like wearing saris anymore’, there are master weavers, gaddidars, who have four-storied show rooms, selling only saris. They have customers who will buy over two dozen expensive saris at a time for a family wedding as giveaways, and aristocratic ladies of Bengal who demand reproductions of old heirlooms regularly. Bollywood couturiers rely heavily on Banarsi saris and film actors wearing them encourage trends among aspirational women. Fashion designers have been working for some years with their special weaving establishments in Varanasi. Often, I have found a beautiful, differently designed scarf among the master weaver’s routine collection. When asked where it is sold, he answers that it is specially ordered by a designer who forbids him from selling it to anyone else. The weaver’s name never appears and he has no idea at what price it is ultimately sold. The difference in cost and sale is most often ten times higher, and the brand label makes all the difference. While we flaunt the names of Indian and foreign designers on our handbags and evening gowns, why is the weaver, who holds the essential knowledge of its techniques in his hands, given the go-by? Even Bollywood boasts of wearing a Ralph Lauren or a Manish Malhotra but never a Maqbool Hussain or Mohamad Junaid of Varanasi, when no new design can evolve without their active involvement and even ideas. Even reproductions and renewals carry the designer’s name and not that of the original weaver’s establishment. Banarsi brocades are known for the rich glimmers of gold and are not every day wear, so my old saris are now holders of memories, wrapped in muslin cloth, and kept in a drawer. New developments in linen yarn and jute are adding to the repertoire, thanks to efforts of textile designers. But until the weaver has the respect and remuneration accorded to our designers, and better systems worked out to find fair space for handloom, powerloom, computerized systems, better yarn supply, efficient dyeing and processing centres, our love of the Banarsi should not be considered enough.

Varanasi has had many names beginning with Baranasi in old Pali scripts, and many others like Avimytaka, Suranshana, Ramya and Kashi, before officially becoming Varanasi only in 1956. The city of Varanasi has an unquantifiable aura of being agelessly old, undefinably spiritual, and offering a sense of peace and continuity when you leave the chaos of the city and sit on the steps of any ghat along the banks, getting lost in the stillness of the ever-moving River Ganga. In the same way, possessing a brocade, a tissue or a tanchoi sari woven by a weaver from Varanasi, wearing it on your wedding day, or possessing one, is like having the reassurance of tradition and continuity in a life of full of sartorial changes. The names of different kinds of weaves and designs of the saris too lend a special story to the ‘Banarsi’ sari, as ubiquitous in a trousseau as the Banarsi paan is at a roadside kiosk. Like the multiple names of Varanasi, sari patterns, motifs and techniques like chaudani pallu, jangla, kinkhab, minakari, , konia shikargah, ashrafi , kadwa kairi, badam, ambi, pan buti, gendabuti, t name a few. Even colours have a variety of names, nilambari for the night sky and kapur safed for camphor white. The weave and the name combine to create a magical identity for each sari. I have always linked my love of the Indian textile aesthetic with pride in the skills of traditional weavers and the imperative to ensure the survival of the heritage they carry in their fingers. Unlettered and unsupported, they create beautiful fabrics to adorn priests, popes, monks and monarchs all over the world. Monasteries are decorated with gyasers woven on the looms of Varanasi, and upholsteries in Middle eastern kingdoms are covered in fabrics made of peacock feathers also woven in Varanasi. My future mother-in-law gave me a rich pink silk Banarsi with golden motifs all over, to wear on my engagement day. My mother showed me her old Banarsi. I chose to wear that on my wedding day and not a freshly bought one which I felt was just a waste of money. It was an old rose tissue in which gold and pink silk threads were interwoven, with a pallu and wide borders decorated with pure zari foliage in the jamdani style. The next day, for the reception I had a more elaborate dark pink and gold striped Banarsi that belonged to my great aunt. I felt I carried the weight of my family history. It was already quite old, so while the gold threads (actually real silver dipped in gold) held out, the ageing silk began giving way, parting company from the zari strips which weighed the silk down. Being from Kerala it was more natural to have chosen a rich Kanjeevaram to wear for one’s wedding, but somehow, Banarsis cropped up at each such auspicious occasion and made me feel much more comfortable than if I had worn a stiff newly bought sari that had no story to tell me. In any household that is sari-wearing, where women still hold on to some customary cultural practices involving the use of craft or textiles, which would be at least 70% of India, a Banarsi brocade is bound to have been bought for a special occasion, and treasured till it frays. Even today, elder women pull out their old handloom treasures, offering them to collectors, museums, exhibition curators, their daughters, and even to designers who want to replicate the intricate old weaves, motifs and tasteful colourways. But what about the weavers themselves? There are weavers living at many levels in Varanasi. At the lowest rung are those who earn a pittance when master weavers give them work. The subsist from order to order with no reassurance of regular work, and often desperation sets in. A rung above them come the weavers who are fortunate enough to be kept on by master weavers whether there are enough orders or not, simply because they need an assured work force at hand when orders are received. Production increases between September and March which encompasses the festive and wedding seasons for all communities. For those who do not wear saris, there is the salwar suit, sharara or lehngas to weave. Despite the buzz in large cosmopolitan cities that sari wearing is going down because ‘girls do not like wearing saris anymore’, there are master weavers, gaddidars, who have four-storied show rooms, selling only saris. They have customers who will buy over two dozen expensive saris at a time for a family wedding as giveaways, and aristocratic ladies of Bengal who demand reproductions of old heirlooms regularly. Bollywood couturiers rely heavily on Banarsi saris and film actors wearing them encourage trends among aspirational women. Fashion designers have been working for some years with their special weaving establishments in Varanasi. Often, I have found a beautiful, differently designed scarf among the master weaver’s routine collection. When asked where it is sold, he answers that it is specially ordered by a designer who forbids him from selling it to anyone else. The weaver’s name never appears and he has no idea at what price it is ultimately sold. The difference in cost and sale is most often ten times higher, and the brand label makes all the difference. While we flaunt the names of Indian and foreign designers on our handbags and evening gowns, why is the weaver, who holds the essential knowledge of its techniques in his hands, given the go-by? Even Bollywood boasts of wearing a Ralph Lauren or a Manish Malhotra but never a Maqbool Hussain or Mohamad Junaid of Varanasi, when no new design can evolve without their active involvement and even ideas. Even reproductions and renewals carry the designer’s name and not that of the original weaver’s establishment. Banarsi brocades are known for the rich glimmers of gold and are not every day wear, so my old saris are now holders of memories, wrapped in muslin cloth, and kept in a drawer. New developments in linen yarn and jute are adding to the repertoire, thanks to efforts of textile designers. But until the weaver has the respect and remuneration accorded to our designers, and better systems worked out to find fair space for handloom, powerloom, computerized systems, better yarn supply, efficient dyeing and processing centres, our love of the Banarsi should not be considered enough.

Why We Must Call Out Craftwashing,

There is a problem when something digitally printed or mechanised is sold as handmade with a skill that takes years to learn

In these days of large industrial production anything handmade implies time and luxury. Weaving a handmade sari takes from three days to six months. Warping which is a necessary part of weaving, takes another five to fifteen days. Hand printing a sari takes from three to 30 days depending on the intricacy and technique. Learning an artisanal craft skill takes months if not years. And becoming good at it takes much longer. Even with an artisan earning only a subsistence wage as they often do, handmade products cost more and take much longer to make than those made on machines. Every single handmade piece looks different from the other and you need an informed customer who enjoys the distinction in these days of cookie cutter looks.

[caption id="attachment_198812" align="alignnone" width="714"] An artisan working on patola sari, Sam Panthaky/AFP[/caption]

An artisan working on patola sari, Sam Panthaky/AFP[/caption]

An artisan working on patola sari, Sam Panthaky/AFP[/caption]

An artisan working on patola sari, Sam Panthaky/AFP[/caption]

Traditionally, handcrafted designs in clothes were often community markers to be worn as made by specific communities and villages. There was an informal copyright in place and each village printed or wove the same few designs to be bought by the same communities. This has changed since the last fifty years or so and craftspeople now liberally borrow designs and techniques from each other. Over the years, prints like ‘Chaubundi’ and ‘Dhaniya’ from Kaladera village in Jaipur district have become familiar to us visually since the same designs have been worn for years and years. Customers may not know the names of these prints but somewhat recognize them. Just as the British used handmade Indian designs in the Lancashire mills and sold the familiar look back to India, designs traditionally used in handcrafted products are also made by mechanised production in India and sold within the country. There is no conversation yet about whether these traditional designs are independent of the handmade process and are available for all of us to use.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="696"] A close up image of 'Dhaniya' print, Meeta Mastani[/caption]

A close up image of 'Dhaniya' print, Meeta Mastani[/caption]

A close up image of 'Dhaniya' print, Meeta Mastani[/caption]

A close up image of 'Dhaniya' print, Meeta Mastani[/caption]

It’s no surprise then that hundreds of products on e-commerce websites and in stores big and small, claim to be handmade when they are not. From leading online marketplaces like Amazon to large retail chains like Fab India, to designers like Ritu Kumar and Anita Dongre or mid-range brands like Biba, everyone is selling products which they imply are handmade in a particular way, when they are not. Others like the humongous Surat saree industry use the handmade design vocabulary freely. All of them [except the Surat saree industry] also sell handmade products through their brands, which makes it difficult for consumers to figure out exactly which products are genuinely handmade and which are not. Even craftspeople themselves sometimes use a faster technique like screen printing in place of block printing or powerloom instead of handloom and then “craftwash” it. The pressure on everyone for large quantities, quick deliveries of pieces that look exactly the same at lower prices push many producers and retailers into this pretend craft. Sometimes the product description tells us about the exact modes of production and how hand crafted it is, and at other times it doesn’t.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="689"] Water painting of a cotton mill in Lancashire England,1885, Shutterstock[/caption]

Water painting of a cotton mill in Lancashire England,1885, Shutterstock[/caption]

Water painting of a cotton mill in Lancashire England,1885, Shutterstock[/caption]

Water painting of a cotton mill in Lancashire England,1885, Shutterstock[/caption]

During the recent conversations around designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s collection for H&M, I thought of the term “craftwashing” It is the process of conveying a false impression, or providing misleading information about how a company's products are more handmade than they actually are. This can be done by referencing something entirely handmade and linking it to the product in question. It can also be done by speaking of a community that usually makes artisanal products and riding on their reputation. The products sold pretend to be hand crafted but are a more or less mechanised version of the hand skill they claim to be. Selling a digital printed version and implying it is a block print is craftwashing as is screen printing when it masquerades as block print. Mill made ‘faux’ silk sounds better than synthetic fabric and is craftwashing as well when it pretends to be handmade silk. Powerloom or mill made fabric projected as handloom is craftwashing.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="693"] A modern powerloom in a textile factory, Shutterstock[/caption]

A modern powerloom in a textile factory, Shutterstock[/caption]

A modern powerloom in a textile factory, Shutterstock[/caption]

A modern powerloom in a textile factory, Shutterstock[/caption]

Handcrafted products include both skill and designs which have culturally evolved over centuries. Many of us want both these aspects of handmade. There are enough customers who want a version of just the design, without the skill, at a cheaper price. A powerloom ikat saree may be good enough for many, despite many who shudder at the thought of it. Innovation is constant and techniques and designs change over time. There is no static ‘tradition’ which has stayed the same forever. Crafts are an expression [for both the maker and the user] just like any other art and are bound to change. The problem arises when it is implied that something is handmade, with a skill that takes years to learn, and it is not handcrafted. Weavers in Western Orissa at village and district levels have ensured that retailers display clear details of powerloom and handloom production for local sales. People are free to buy the cheaper powerloom versions in an informed manner.

[caption id="" align="alignnone" width="710"] An image of automatic embroidery machine in a textile factory, Shutterstock[/caption]

An image of automatic embroidery machine in a textile factory, Shutterstock[/caption]

An image of automatic embroidery machine in a textile factory, Shutterstock[/caption]

An image of automatic embroidery machine in a textile factory, Shutterstock[/caption]

At a time when anything goes in design and production, the best we can hope for and hold our producers and retailers to is transparency - both in process and in design. In a continuously evolving market, our craft associations need to bring out best practices keeping producers, retailers and customers in mind. And we need to reward the best and the most honest producers and retailers with our purchases.

Banner: Photo of a machine printing digitally used for representational purpose. Shutterstock.

Meeta Mastani the co-founder of Bindaas Unlimited works at the intersection of sustainable development, culture, craft, design, arts and retail.

First Published in The Voice of Fashion, September 28, 2021.

With a Change of Garb, Smriti Irani Could Transform Handlooms, From Irrelevant to Dynamic

[caption id="attachment_198244" align="aligncenter" width="480"] Mohammad Ismail, a handloom weaver in Varanasi. Credit: Anandamoy/ Flickr[/caption]

Social media is full of jokes about how, in the best traditions of Indian patriarchy, Smriti Irani was found unsuited for higher education and told to go make clothes for her dolls. Other memes have her locking her textbooks in a cupboard and sitting down to weave lotus symbols on saris. The jokes reveal two deeply entrenched public perceptions: first, that managing textiles – despite being the largest employment sector after agriculture – is a demotion; second, and more surprisingly, that the textile ministry is all about handlooms and the traditional weavers that make them. This is gratifying, but ironic.

In actual fact, the handloom sector is a small embattled section of a ministry in which handlooms are totally overshadowed by the overpowering presence of the mill and powerloom sector. Their aggressive, organised and well-funded lobbies make sure that the voice and needs of the handloom weaver are completely ignored. Bureaucrats in charge of the sector change seats quite rapidly; it attracts neither eyeballs nor kickbacks. They seldom understand its complex nature. One senior bureaucrat called it a ‘sunset industry’, ignoring the fact that everywhere else in the world ‘hand-spun’, ‘hand-woven’ and ‘handmade’ have become desired designer labels. In New York, pure Egyptian cotton sheets retail for the equivalent of Rs 25,000.

The 17th century traveller Francois Pyrard de Laval wrote that Indian “cotton cloth was the first global commodity”, and “the growing of cotton, the spinning of yarn and the weaving and finishing of cloth provided employment and income to millions … Everyone from the Cape of Good Hope to China, man and woman, is clothed from head to foot in the product of Indian looms.” Today, they are clothed in Chinese goods instead.

Always more savvy than us, China regularly imports Indian weavers to teach their own craftspeople our skills. Chinese Banarsis, pashminas, machine-made chikan embroidery and faux-Kutch mirror work are flooding the market and finding ready takers, even in India. Last year, when I was in China, it had just been announced that craft was one of the eight major sectors they were going to concentrate on over the next decade. Master craftspeople are given subsidised housing and work in luxurious fully-equipped environs – complete with air-conditioning and piped music. Their salaries reflect their perceived status in society. They are part of the professional middle-class, encouraged to think big and add value to their products, and given every means to learn to do so.

A tragedy on all fronts

Meanwhile, we in India ignore our own handlooms industry. It is ironic because this is precisely the sector that could make the ‘Make in India’ and ‘Skill India’ initiatives work. While we try to painfully acquire the skills and resources that other advanced countries acquired decades ago, we ignore this existing goldmine and the advantage we have of a foot in multiple centuries. Instead of investing in, developing and promoting our unique skill sets and knowledge systems, we are allowing them to die. For lack of equal opportunity, their owners are leaving the sector in droves.

The weavers in Nagpur – once a centre for wonderful handlooms – no longer weave saris because there are no longer skilled local artisans to make and repair the looms. And while we celebrate the wonderful Kashmiri shawl-makers, it is tragic that only 1% of the world’s production of pashmina yarn comes from India. And the quality is so poor that only 10% of this 1% is internationally graded as pashmina*. Shawl manufacturers in India, once the cradle of pashmina yarn, now import raw pashmina – from China and Mongolia, and even the UK.

Weavers and craftspeople are dismissed as ‘picturesque’ heritage and culture, or seen as part of a primitive technology that is irrelevant to a developing economy and will inevitably die. What a tragedy. Shortsighted, too, since the ‘modern’ skills currently being expensively promoted encourage wholesale migration to India’s overburdened cities, placing a further load on our already inadequate urban infrastructure. On the other hand, textile skills are based in rural India, with minimal carbon imprint, perfectly suited to rural production systems and social structures. They also – and this is crucially important – bring agriculturists and rural women into the economy, creating double-income households in otherwise poverty-stricken areas.

Apart from scaling up existing weaver communities, there is huge scope for creating ancillary skills that service them: (i) The cultivation and production of raw material (cotton, silk, hussar, linen, jute and wool yarn); (ii) pattern making, embroidery, block and screen printing dyeing; (iii) making of tools and equipment, including looms, spindles and shuttles; (iv) warping of looms, cutting, tailoring, accessorising, washing and dry cleaning; (v) packaging, entrepreneurship development for marketing; and, of course, (vi) cultivation and development of all those exciting new fibres such as banana leaves, nettle and water chestnuts.

This would create additional employment in crafts pockets, as well enable greater professionalism and more productivity in the existing crafts community.

Dastkar’s own intervention with Berozgar Mahila Kalyan Samiti in Bihar, and the transformation of rural spinners and weavers from bonded labour into a several-crore-turnover enterprise, is another example of undervalued traditional skills becoming a lucrative source of employment and earning. However, today, at the apogee of their demand, they are again facing problems due to the unavailability of raw Tussar, once found wild in their forests. This is a reminder of the dependency of craft traditions on many external factors: market linkages, access to finance, design and market information, appropriate raw material – all of which are necessary to build a prosperous India.

New ways of seeing

In order to realise the potential of our own unique skill-sets, creativity and expertise, we need to relook the whole way we deal with the sector. We need to realise that though handloom weavers number in the millions, each family is a unique specialised unit, working in hundreds of different traditions, often with their own special techniques and design directory – and with their own individual needs. To lump them together in generic government cluster development schemes or textile parks does not necessarily work. They should be treated like other entrepreneurs, with easy access to resources and investment.

A Kanjeeveram sari weaver with the potential to weave a brocaded wedding sari worth a lakh rupees is quite different from a weaver in Barabanki making coarse cotton bedsheets. Their raw materials, R&D requirements, production capacities, design references, storage needs and even potential markets are all quite different. To position them together in an open-air Handloom Expo is dumbing down the potential of both. One needs the hushed exclusivity of a carefully-lit showroom, saris wrapped in fine muslin covers, being reverently unfolded one by one; the other needs wholesale orders.

One major factor in the decline in the numbers of young craftspeople leaving the sector (an estimated 10-15% every decade, an acknowledged fact, taken from the census and handicrafts board figures of the last several decades*) is the conflict between the need for formal education and learning the family craft skill. Either they become unlettered artisans, placed very low in the social and professional hierarchy, or – if they do opt for formal education – they lose their inherent dexterity, but often do not qualify for alternative occupations.

If craftspeople are to be on par with other professionals, they need skills other than simply craftsmanship, skills like entrepreneurship, merchandising, finance, IT know-how, access to technology and contemporary design. Where can they acquire these skills? How do we embed these functions in crafts communities, without impacting the cultural and social subtleties of their traditions and ways of life?

One example is comprised of the young craftspeople of Kutch and Kashmir, who have perceived the advantages of learning the terminology and practice of design, graphic communication and entrepreneurial skills, along with English and accountancy, as a way to upgrade and value-add to the skills they have inherited. Institutions like Judy Frater’s path-breaking Kala Raksha Vidyalaya, the Craft Development Institute in Srinagar, the Handloom School and now the Somaiya Kala Vidya, have given them the confidence and ability to use their creativity in new ways. They look at their traditions as a calling card, not a cage. We need to replicate these modules all over India sensitively, taking weavers and handlooms into the global marketplace and 21st century.

Philosopher historian Ananda Coomaraswamy said a century ago: “The most important thing that India can give to the rest of the world is simply its Indianness. If it were to substitute this for a cosmopolitan veneer, it would have to come before the world empty handed.” Politicians, bureaucrats and economists, trying to turn us from ‘developing’ to ‘developed’, need to recognise the value of existing indigenous technologies, skill sets and knowledge systems. If we can do it for yoga, we can surely do it for handlooms, which would benefit hundreds of millions.

Hopefully, Irani’s pugnacious, proactive nature will find an outlet combating the dominant view of handlooms as an irrelevant, outdated part of our past. If nurtured, they could be such a dynamic part of our economic future.

Mohammad Ismail, a handloom weaver in Varanasi. Credit: Anandamoy/ Flickr[/caption]

Social media is full of jokes about how, in the best traditions of Indian patriarchy, Smriti Irani was found unsuited for higher education and told to go make clothes for her dolls. Other memes have her locking her textbooks in a cupboard and sitting down to weave lotus symbols on saris. The jokes reveal two deeply entrenched public perceptions: first, that managing textiles – despite being the largest employment sector after agriculture – is a demotion; second, and more surprisingly, that the textile ministry is all about handlooms and the traditional weavers that make them. This is gratifying, but ironic.

In actual fact, the handloom sector is a small embattled section of a ministry in which handlooms are totally overshadowed by the overpowering presence of the mill and powerloom sector. Their aggressive, organised and well-funded lobbies make sure that the voice and needs of the handloom weaver are completely ignored. Bureaucrats in charge of the sector change seats quite rapidly; it attracts neither eyeballs nor kickbacks. They seldom understand its complex nature. One senior bureaucrat called it a ‘sunset industry’, ignoring the fact that everywhere else in the world ‘hand-spun’, ‘hand-woven’ and ‘handmade’ have become desired designer labels. In New York, pure Egyptian cotton sheets retail for the equivalent of Rs 25,000.

The 17th century traveller Francois Pyrard de Laval wrote that Indian “cotton cloth was the first global commodity”, and “the growing of cotton, the spinning of yarn and the weaving and finishing of cloth provided employment and income to millions … Everyone from the Cape of Good Hope to China, man and woman, is clothed from head to foot in the product of Indian looms.” Today, they are clothed in Chinese goods instead.

Always more savvy than us, China regularly imports Indian weavers to teach their own craftspeople our skills. Chinese Banarsis, pashminas, machine-made chikan embroidery and faux-Kutch mirror work are flooding the market and finding ready takers, even in India. Last year, when I was in China, it had just been announced that craft was one of the eight major sectors they were going to concentrate on over the next decade. Master craftspeople are given subsidised housing and work in luxurious fully-equipped environs – complete with air-conditioning and piped music. Their salaries reflect their perceived status in society. They are part of the professional middle-class, encouraged to think big and add value to their products, and given every means to learn to do so.

A tragedy on all fronts

Meanwhile, we in India ignore our own handlooms industry. It is ironic because this is precisely the sector that could make the ‘Make in India’ and ‘Skill India’ initiatives work. While we try to painfully acquire the skills and resources that other advanced countries acquired decades ago, we ignore this existing goldmine and the advantage we have of a foot in multiple centuries. Instead of investing in, developing and promoting our unique skill sets and knowledge systems, we are allowing them to die. For lack of equal opportunity, their owners are leaving the sector in droves.

The weavers in Nagpur – once a centre for wonderful handlooms – no longer weave saris because there are no longer skilled local artisans to make and repair the looms. And while we celebrate the wonderful Kashmiri shawl-makers, it is tragic that only 1% of the world’s production of pashmina yarn comes from India. And the quality is so poor that only 10% of this 1% is internationally graded as pashmina*. Shawl manufacturers in India, once the cradle of pashmina yarn, now import raw pashmina – from China and Mongolia, and even the UK.

Weavers and craftspeople are dismissed as ‘picturesque’ heritage and culture, or seen as part of a primitive technology that is irrelevant to a developing economy and will inevitably die. What a tragedy. Shortsighted, too, since the ‘modern’ skills currently being expensively promoted encourage wholesale migration to India’s overburdened cities, placing a further load on our already inadequate urban infrastructure. On the other hand, textile skills are based in rural India, with minimal carbon imprint, perfectly suited to rural production systems and social structures. They also – and this is crucially important – bring agriculturists and rural women into the economy, creating double-income households in otherwise poverty-stricken areas.

Apart from scaling up existing weaver communities, there is huge scope for creating ancillary skills that service them: (i) The cultivation and production of raw material (cotton, silk, hussar, linen, jute and wool yarn); (ii) pattern making, embroidery, block and screen printing dyeing; (iii) making of tools and equipment, including looms, spindles and shuttles; (iv) warping of looms, cutting, tailoring, accessorising, washing and dry cleaning; (v) packaging, entrepreneurship development for marketing; and, of course, (vi) cultivation and development of all those exciting new fibres such as banana leaves, nettle and water chestnuts.

This would create additional employment in crafts pockets, as well enable greater professionalism and more productivity in the existing crafts community.

Dastkar’s own intervention with Berozgar Mahila Kalyan Samiti in Bihar, and the transformation of rural spinners and weavers from bonded labour into a several-crore-turnover enterprise, is another example of undervalued traditional skills becoming a lucrative source of employment and earning. However, today, at the apogee of their demand, they are again facing problems due to the unavailability of raw Tussar, once found wild in their forests. This is a reminder of the dependency of craft traditions on many external factors: market linkages, access to finance, design and market information, appropriate raw material – all of which are necessary to build a prosperous India.

New ways of seeing

In order to realise the potential of our own unique skill-sets, creativity and expertise, we need to relook the whole way we deal with the sector. We need to realise that though handloom weavers number in the millions, each family is a unique specialised unit, working in hundreds of different traditions, often with their own special techniques and design directory – and with their own individual needs. To lump them together in generic government cluster development schemes or textile parks does not necessarily work. They should be treated like other entrepreneurs, with easy access to resources and investment.

A Kanjeeveram sari weaver with the potential to weave a brocaded wedding sari worth a lakh rupees is quite different from a weaver in Barabanki making coarse cotton bedsheets. Their raw materials, R&D requirements, production capacities, design references, storage needs and even potential markets are all quite different. To position them together in an open-air Handloom Expo is dumbing down the potential of both. One needs the hushed exclusivity of a carefully-lit showroom, saris wrapped in fine muslin covers, being reverently unfolded one by one; the other needs wholesale orders.

One major factor in the decline in the numbers of young craftspeople leaving the sector (an estimated 10-15% every decade, an acknowledged fact, taken from the census and handicrafts board figures of the last several decades*) is the conflict between the need for formal education and learning the family craft skill. Either they become unlettered artisans, placed very low in the social and professional hierarchy, or – if they do opt for formal education – they lose their inherent dexterity, but often do not qualify for alternative occupations.

If craftspeople are to be on par with other professionals, they need skills other than simply craftsmanship, skills like entrepreneurship, merchandising, finance, IT know-how, access to technology and contemporary design. Where can they acquire these skills? How do we embed these functions in crafts communities, without impacting the cultural and social subtleties of their traditions and ways of life?

One example is comprised of the young craftspeople of Kutch and Kashmir, who have perceived the advantages of learning the terminology and practice of design, graphic communication and entrepreneurial skills, along with English and accountancy, as a way to upgrade and value-add to the skills they have inherited. Institutions like Judy Frater’s path-breaking Kala Raksha Vidyalaya, the Craft Development Institute in Srinagar, the Handloom School and now the Somaiya Kala Vidya, have given them the confidence and ability to use their creativity in new ways. They look at their traditions as a calling card, not a cage. We need to replicate these modules all over India sensitively, taking weavers and handlooms into the global marketplace and 21st century.

Philosopher historian Ananda Coomaraswamy said a century ago: “The most important thing that India can give to the rest of the world is simply its Indianness. If it were to substitute this for a cosmopolitan veneer, it would have to come before the world empty handed.” Politicians, bureaucrats and economists, trying to turn us from ‘developing’ to ‘developed’, need to recognise the value of existing indigenous technologies, skill sets and knowledge systems. If we can do it for yoga, we can surely do it for handlooms, which would benefit hundreds of millions.

Hopefully, Irani’s pugnacious, proactive nature will find an outlet combating the dominant view of handlooms as an irrelevant, outdated part of our past. If nurtured, they could be such a dynamic part of our economic future.

[caption id="attachment_198244" align="aligncenter" width="480"]

Mohammad Ismail, a handloom weaver in Varanasi. Credit: Anandamoy/ Flickr[/caption]

Social media is full of jokes about how, in the best traditions of Indian patriarchy, Smriti Irani was found unsuited for higher education and told to go make clothes for her dolls. Other memes have her locking her textbooks in a cupboard and sitting down to weave lotus symbols on saris. The jokes reveal two deeply entrenched public perceptions: first, that managing textiles – despite being the largest employment sector after agriculture – is a demotion; second, and more surprisingly, that the textile ministry is all about handlooms and the traditional weavers that make them. This is gratifying, but ironic.

In actual fact, the handloom sector is a small embattled section of a ministry in which handlooms are totally overshadowed by the overpowering presence of the mill and powerloom sector. Their aggressive, organised and well-funded lobbies make sure that the voice and needs of the handloom weaver are completely ignored. Bureaucrats in charge of the sector change seats quite rapidly; it attracts neither eyeballs nor kickbacks. They seldom understand its complex nature. One senior bureaucrat called it a ‘sunset industry’, ignoring the fact that everywhere else in the world ‘hand-spun’, ‘hand-woven’ and ‘handmade’ have become desired designer labels. In New York, pure Egyptian cotton sheets retail for the equivalent of Rs 25,000.

The 17th century traveller Francois Pyrard de Laval wrote that Indian “cotton cloth was the first global commodity”, and “the growing of cotton, the spinning of yarn and the weaving and finishing of cloth provided employment and income to millions … Everyone from the Cape of Good Hope to China, man and woman, is clothed from head to foot in the product of Indian looms.” Today, they are clothed in Chinese goods instead.

Always more savvy than us, China regularly imports Indian weavers to teach their own craftspeople our skills. Chinese Banarsis, pashminas, machine-made chikan embroidery and faux-Kutch mirror work are flooding the market and finding ready takers, even in India. Last year, when I was in China, it had just been announced that craft was one of the eight major sectors they were going to concentrate on over the next decade. Master craftspeople are given subsidised housing and work in luxurious fully-equipped environs – complete with air-conditioning and piped music. Their salaries reflect their perceived status in society. They are part of the professional middle-class, encouraged to think big and add value to their products, and given every means to learn to do so.

A tragedy on all fronts

Meanwhile, we in India ignore our own handlooms industry. It is ironic because this is precisely the sector that could make the ‘Make in India’ and ‘Skill India’ initiatives work. While we try to painfully acquire the skills and resources that other advanced countries acquired decades ago, we ignore this existing goldmine and the advantage we have of a foot in multiple centuries. Instead of investing in, developing and promoting our unique skill sets and knowledge systems, we are allowing them to die. For lack of equal opportunity, their owners are leaving the sector in droves.

The weavers in Nagpur – once a centre for wonderful handlooms – no longer weave saris because there are no longer skilled local artisans to make and repair the looms. And while we celebrate the wonderful Kashmiri shawl-makers, it is tragic that only 1% of the world’s production of pashmina yarn comes from India. And the quality is so poor that only 10% of this 1% is internationally graded as pashmina*. Shawl manufacturers in India, once the cradle of pashmina yarn, now import raw pashmina – from China and Mongolia, and even the UK.

Weavers and craftspeople are dismissed as ‘picturesque’ heritage and culture, or seen as part of a primitive technology that is irrelevant to a developing economy and will inevitably die. What a tragedy. Shortsighted, too, since the ‘modern’ skills currently being expensively promoted encourage wholesale migration to India’s overburdened cities, placing a further load on our already inadequate urban infrastructure. On the other hand, textile skills are based in rural India, with minimal carbon imprint, perfectly suited to rural production systems and social structures. They also – and this is crucially important – bring agriculturists and rural women into the economy, creating double-income households in otherwise poverty-stricken areas.

Apart from scaling up existing weaver communities, there is huge scope for creating ancillary skills that service them: (i) The cultivation and production of raw material (cotton, silk, hussar, linen, jute and wool yarn); (ii) pattern making, embroidery, block and screen printing dyeing; (iii) making of tools and equipment, including looms, spindles and shuttles; (iv) warping of looms, cutting, tailoring, accessorising, washing and dry cleaning; (v) packaging, entrepreneurship development for marketing; and, of course, (vi) cultivation and development of all those exciting new fibres such as banana leaves, nettle and water chestnuts.

This would create additional employment in crafts pockets, as well enable greater professionalism and more productivity in the existing crafts community.

Dastkar’s own intervention with Berozgar Mahila Kalyan Samiti in Bihar, and the transformation of rural spinners and weavers from bonded labour into a several-crore-turnover enterprise, is another example of undervalued traditional skills becoming a lucrative source of employment and earning. However, today, at the apogee of their demand, they are again facing problems due to the unavailability of raw Tussar, once found wild in their forests. This is a reminder of the dependency of craft traditions on many external factors: market linkages, access to finance, design and market information, appropriate raw material – all of which are necessary to build a prosperous India.

New ways of seeing

In order to realise the potential of our own unique skill-sets, creativity and expertise, we need to relook the whole way we deal with the sector. We need to realise that though handloom weavers number in the millions, each family is a unique specialised unit, working in hundreds of different traditions, often with their own special techniques and design directory – and with their own individual needs. To lump them together in generic government cluster development schemes or textile parks does not necessarily work. They should be treated like other entrepreneurs, with easy access to resources and investment.

A Kanjeeveram sari weaver with the potential to weave a brocaded wedding sari worth a lakh rupees is quite different from a weaver in Barabanki making coarse cotton bedsheets. Their raw materials, R&D requirements, production capacities, design references, storage needs and even potential markets are all quite different. To position them together in an open-air Handloom Expo is dumbing down the potential of both. One needs the hushed exclusivity of a carefully-lit showroom, saris wrapped in fine muslin covers, being reverently unfolded one by one; the other needs wholesale orders.

One major factor in the decline in the numbers of young craftspeople leaving the sector (an estimated 10-15% every decade, an acknowledged fact, taken from the census and handicrafts board figures of the last several decades*) is the conflict between the need for formal education and learning the family craft skill. Either they become unlettered artisans, placed very low in the social and professional hierarchy, or – if they do opt for formal education – they lose their inherent dexterity, but often do not qualify for alternative occupations.

If craftspeople are to be on par with other professionals, they need skills other than simply craftsmanship, skills like entrepreneurship, merchandising, finance, IT know-how, access to technology and contemporary design. Where can they acquire these skills? How do we embed these functions in crafts communities, without impacting the cultural and social subtleties of their traditions and ways of life?

One example is comprised of the young craftspeople of Kutch and Kashmir, who have perceived the advantages of learning the terminology and practice of design, graphic communication and entrepreneurial skills, along with English and accountancy, as a way to upgrade and value-add to the skills they have inherited. Institutions like Judy Frater’s path-breaking Kala Raksha Vidyalaya, the Craft Development Institute in Srinagar, the Handloom School and now the Somaiya Kala Vidya, have given them the confidence and ability to use their creativity in new ways. They look at their traditions as a calling card, not a cage. We need to replicate these modules all over India sensitively, taking weavers and handlooms into the global marketplace and 21st century.

Philosopher historian Ananda Coomaraswamy said a century ago: “The most important thing that India can give to the rest of the world is simply its Indianness. If it were to substitute this for a cosmopolitan veneer, it would have to come before the world empty handed.” Politicians, bureaucrats and economists, trying to turn us from ‘developing’ to ‘developed’, need to recognise the value of existing indigenous technologies, skill sets and knowledge systems. If we can do it for yoga, we can surely do it for handlooms, which would benefit hundreds of millions.

Hopefully, Irani’s pugnacious, proactive nature will find an outlet combating the dominant view of handlooms as an irrelevant, outdated part of our past. If nurtured, they could be such a dynamic part of our economic future.

Mohammad Ismail, a handloom weaver in Varanasi. Credit: Anandamoy/ Flickr[/caption]

Social media is full of jokes about how, in the best traditions of Indian patriarchy, Smriti Irani was found unsuited for higher education and told to go make clothes for her dolls. Other memes have her locking her textbooks in a cupboard and sitting down to weave lotus symbols on saris. The jokes reveal two deeply entrenched public perceptions: first, that managing textiles – despite being the largest employment sector after agriculture – is a demotion; second, and more surprisingly, that the textile ministry is all about handlooms and the traditional weavers that make them. This is gratifying, but ironic.

In actual fact, the handloom sector is a small embattled section of a ministry in which handlooms are totally overshadowed by the overpowering presence of the mill and powerloom sector. Their aggressive, organised and well-funded lobbies make sure that the voice and needs of the handloom weaver are completely ignored. Bureaucrats in charge of the sector change seats quite rapidly; it attracts neither eyeballs nor kickbacks. They seldom understand its complex nature. One senior bureaucrat called it a ‘sunset industry’, ignoring the fact that everywhere else in the world ‘hand-spun’, ‘hand-woven’ and ‘handmade’ have become desired designer labels. In New York, pure Egyptian cotton sheets retail for the equivalent of Rs 25,000.

The 17th century traveller Francois Pyrard de Laval wrote that Indian “cotton cloth was the first global commodity”, and “the growing of cotton, the spinning of yarn and the weaving and finishing of cloth provided employment and income to millions … Everyone from the Cape of Good Hope to China, man and woman, is clothed from head to foot in the product of Indian looms.” Today, they are clothed in Chinese goods instead.

Always more savvy than us, China regularly imports Indian weavers to teach their own craftspeople our skills. Chinese Banarsis, pashminas, machine-made chikan embroidery and faux-Kutch mirror work are flooding the market and finding ready takers, even in India. Last year, when I was in China, it had just been announced that craft was one of the eight major sectors they were going to concentrate on over the next decade. Master craftspeople are given subsidised housing and work in luxurious fully-equipped environs – complete with air-conditioning and piped music. Their salaries reflect their perceived status in society. They are part of the professional middle-class, encouraged to think big and add value to their products, and given every means to learn to do so.

A tragedy on all fronts

Meanwhile, we in India ignore our own handlooms industry. It is ironic because this is precisely the sector that could make the ‘Make in India’ and ‘Skill India’ initiatives work. While we try to painfully acquire the skills and resources that other advanced countries acquired decades ago, we ignore this existing goldmine and the advantage we have of a foot in multiple centuries. Instead of investing in, developing and promoting our unique skill sets and knowledge systems, we are allowing them to die. For lack of equal opportunity, their owners are leaving the sector in droves.

The weavers in Nagpur – once a centre for wonderful handlooms – no longer weave saris because there are no longer skilled local artisans to make and repair the looms. And while we celebrate the wonderful Kashmiri shawl-makers, it is tragic that only 1% of the world’s production of pashmina yarn comes from India. And the quality is so poor that only 10% of this 1% is internationally graded as pashmina*. Shawl manufacturers in India, once the cradle of pashmina yarn, now import raw pashmina – from China and Mongolia, and even the UK.

Weavers and craftspeople are dismissed as ‘picturesque’ heritage and culture, or seen as part of a primitive technology that is irrelevant to a developing economy and will inevitably die. What a tragedy. Shortsighted, too, since the ‘modern’ skills currently being expensively promoted encourage wholesale migration to India’s overburdened cities, placing a further load on our already inadequate urban infrastructure. On the other hand, textile skills are based in rural India, with minimal carbon imprint, perfectly suited to rural production systems and social structures. They also – and this is crucially important – bring agriculturists and rural women into the economy, creating double-income households in otherwise poverty-stricken areas.

Apart from scaling up existing weaver communities, there is huge scope for creating ancillary skills that service them: (i) The cultivation and production of raw material (cotton, silk, hussar, linen, jute and wool yarn); (ii) pattern making, embroidery, block and screen printing dyeing; (iii) making of tools and equipment, including looms, spindles and shuttles; (iv) warping of looms, cutting, tailoring, accessorising, washing and dry cleaning; (v) packaging, entrepreneurship development for marketing; and, of course, (vi) cultivation and development of all those exciting new fibres such as banana leaves, nettle and water chestnuts.

This would create additional employment in crafts pockets, as well enable greater professionalism and more productivity in the existing crafts community.

Dastkar’s own intervention with Berozgar Mahila Kalyan Samiti in Bihar, and the transformation of rural spinners and weavers from bonded labour into a several-crore-turnover enterprise, is another example of undervalued traditional skills becoming a lucrative source of employment and earning. However, today, at the apogee of their demand, they are again facing problems due to the unavailability of raw Tussar, once found wild in their forests. This is a reminder of the dependency of craft traditions on many external factors: market linkages, access to finance, design and market information, appropriate raw material – all of which are necessary to build a prosperous India.

New ways of seeing

In order to realise the potential of our own unique skill-sets, creativity and expertise, we need to relook the whole way we deal with the sector. We need to realise that though handloom weavers number in the millions, each family is a unique specialised unit, working in hundreds of different traditions, often with their own special techniques and design directory – and with their own individual needs. To lump them together in generic government cluster development schemes or textile parks does not necessarily work. They should be treated like other entrepreneurs, with easy access to resources and investment.

A Kanjeeveram sari weaver with the potential to weave a brocaded wedding sari worth a lakh rupees is quite different from a weaver in Barabanki making coarse cotton bedsheets. Their raw materials, R&D requirements, production capacities, design references, storage needs and even potential markets are all quite different. To position them together in an open-air Handloom Expo is dumbing down the potential of both. One needs the hushed exclusivity of a carefully-lit showroom, saris wrapped in fine muslin covers, being reverently unfolded one by one; the other needs wholesale orders.

One major factor in the decline in the numbers of young craftspeople leaving the sector (an estimated 10-15% every decade, an acknowledged fact, taken from the census and handicrafts board figures of the last several decades*) is the conflict between the need for formal education and learning the family craft skill. Either they become unlettered artisans, placed very low in the social and professional hierarchy, or – if they do opt for formal education – they lose their inherent dexterity, but often do not qualify for alternative occupations.

If craftspeople are to be on par with other professionals, they need skills other than simply craftsmanship, skills like entrepreneurship, merchandising, finance, IT know-how, access to technology and contemporary design. Where can they acquire these skills? How do we embed these functions in crafts communities, without impacting the cultural and social subtleties of their traditions and ways of life?

One example is comprised of the young craftspeople of Kutch and Kashmir, who have perceived the advantages of learning the terminology and practice of design, graphic communication and entrepreneurial skills, along with English and accountancy, as a way to upgrade and value-add to the skills they have inherited. Institutions like Judy Frater’s path-breaking Kala Raksha Vidyalaya, the Craft Development Institute in Srinagar, the Handloom School and now the Somaiya Kala Vidya, have given them the confidence and ability to use their creativity in new ways. They look at their traditions as a calling card, not a cage. We need to replicate these modules all over India sensitively, taking weavers and handlooms into the global marketplace and 21st century.

Philosopher historian Ananda Coomaraswamy said a century ago: “The most important thing that India can give to the rest of the world is simply its Indianness. If it were to substitute this for a cosmopolitan veneer, it would have to come before the world empty handed.” Politicians, bureaucrats and economists, trying to turn us from ‘developing’ to ‘developed’, need to recognise the value of existing indigenous technologies, skill sets and knowledge systems. If we can do it for yoga, we can surely do it for handlooms, which would benefit hundreds of millions.

Hopefully, Irani’s pugnacious, proactive nature will find an outlet combating the dominant view of handlooms as an irrelevant, outdated part of our past. If nurtured, they could be such a dynamic part of our economic future.

- These statistics are from a report previously accessed by the author.

Wood Carving of Basti Pathuria Sahi, Odisha,

Looking back into a tradition of craftsmanship going back generations National Award Winner Ashok Kumar Mohapatra, 37, speaks with pride of his craft and vocation of wood carving. Born into a family of traditional stone carvers at Basti Pathuria Sahi in the historic town of Puri (Odisha) he received his first lessons and training from his father and uncles, who in turn had learnt their consummate art from Shri Giridhari Lal Mohapatra his talented and distinguished grandfather. The Mohapatras have earned a name for excellence in stone carving, statue making and temple building. They trace their ancestry to the builders of the acclaimed temple of Lord Jagganath at Puri. A smile of satisfaction touches Ashok Kumars face as he reminisces how as a child he enjoyed polishing stones on way to school and even at that young age earned a little money selling small images of Lord Jagganath near the beach. The excellence in his craft came later under the careful guidance of his father Madan Mohan Mohapatra who recognized in his son talent and capability to take on the family inheritance. While the older generation had mastered the craft of carving granite, sandstone and red stone Ashok Kumar made a niche for himself as an entrepreneur carving in wood. Interestingly this happened when a businessman marketing his fathers carvings suggested that he try his hand at wood as many Japanese tourists were looking for crafts in a lighter medium.

The wood’s he chose to work on are ‘pani gambhari’ a soft creamish white teak along with the harder ‘phula gambhari’ and the darker sisu or rosewood for heavier pieces, which he buys from Puri. While features in painted wood carvings are usually less defined and diffuse, those done on ‘gambhari’ are sharp and fine and attain an exquisite work finish resembling the workmanship of sculptors.

The motifs include various stylized animals and birds, elephant, lion, tiger, bull, peacock etc, Radha, Krishna and sakhis and the three most popular deities of the Puri temple, Jaganath, Balabhadra and Subhadra. The three chariots of the Puri car festival are decorated with wooden images depicting various deities as parswadevatas. A popular image is from the Mahabharata, of Krishna the sarathi or charioteer teaching Arjuna the tenets of the Gita while guiding the horses harnessed in front. Excellently proportioned and finished to fine smoothness these wood carvings depicting myths, legends and folklore are a collector’s delight. Good examples of the work of the wood carvers of Odisha can be found in temple ceilings and carved wooden beams and doors in places like Charchika temple, Buguda, Banki, Birnchinarayan temple, Kapilas, Siva temple and the Laxmi Nrusingha temple at Berhampur.

Ashok Kumar’s winning work is the ‘Buddha Kila’ a mural composed of many scenes from the life of the Buddha. A relief work composed on a single plaque of wood it has taken him two years and seven months to complete. With grace, delicacy and beauty the figures present different stages of Bhagwan Buddha’s life. The serene Buddha and his life fascinated the young Ashok Kumar. Seeing images brought to life in stone by his father brought in him a dream of some day doing the same. While many craftsmen were depicting the life stories of Gods and Goddesses of the Hindu pantheon the life of Buddha was ignored for reasons unknown. His award winning Buddha collage is culmination of single minded devotion to his art.

Ashok Kumar is happy being in Delhi to show his craft to a wider audience and to receive the National Award for Master Craftsperson’s given by the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. This exposure gives him an opportunity to reach out to a wider audience and contact more buyers. His one regret as he says is “works such as mine with an earthy character and rough texture, with no lacquer finish do not find too many ready buyers anymore. Buyers are today looking for glitter and shine…even in engravings and carvings. The market is changing fast and I will have to consider innovating”. But then cheerfully adds” however there still are a few who appreciate that not all that glitters is gold”.

A smile of satisfaction touches Ashok Kumars face as he reminisces how as a child he enjoyed polishing stones on way to school and even at that young age earned a little money selling small images of Lord Jagganath near the beach. The excellence in his craft came later under the careful guidance of his father Madan Mohan Mohapatra who recognized in his son talent and capability to take on the family inheritance. While the older generation had mastered the craft of carving granite, sandstone and red stone Ashok Kumar made a niche for himself as an entrepreneur carving in wood. Interestingly this happened when a businessman marketing his fathers carvings suggested that he try his hand at wood as many Japanese tourists were looking for crafts in a lighter medium.

The wood’s he chose to work on are ‘pani gambhari’ a soft creamish white teak along with the harder ‘phula gambhari’ and the darker sisu or rosewood for heavier pieces, which he buys from Puri. While features in painted wood carvings are usually less defined and diffuse, those done on ‘gambhari’ are sharp and fine and attain an exquisite work finish resembling the workmanship of sculptors.

The motifs include various stylized animals and birds, elephant, lion, tiger, bull, peacock etc, Radha, Krishna and sakhis and the three most popular deities of the Puri temple, Jaganath, Balabhadra and Subhadra. The three chariots of the Puri car festival are decorated with wooden images depicting various deities as parswadevatas. A popular image is from the Mahabharata, of Krishna the sarathi or charioteer teaching Arjuna the tenets of the Gita while guiding the horses harnessed in front. Excellently proportioned and finished to fine smoothness these wood carvings depicting myths, legends and folklore are a collector’s delight. Good examples of the work of the wood carvers of Odisha can be found in temple ceilings and carved wooden beams and doors in places like Charchika temple, Buguda, Banki, Birnchinarayan temple, Kapilas, Siva temple and the Laxmi Nrusingha temple at Berhampur.

Ashok Kumar’s winning work is the ‘Buddha Kila’ a mural composed of many scenes from the life of the Buddha. A relief work composed on a single plaque of wood it has taken him two years and seven months to complete. With grace, delicacy and beauty the figures present different stages of Bhagwan Buddha’s life. The serene Buddha and his life fascinated the young Ashok Kumar. Seeing images brought to life in stone by his father brought in him a dream of some day doing the same. While many craftsmen were depicting the life stories of Gods and Goddesses of the Hindu pantheon the life of Buddha was ignored for reasons unknown. His award winning Buddha collage is culmination of single minded devotion to his art.

Ashok Kumar is happy being in Delhi to show his craft to a wider audience and to receive the National Award for Master Craftsperson’s given by the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. This exposure gives him an opportunity to reach out to a wider audience and contact more buyers. His one regret as he says is “works such as mine with an earthy character and rough texture, with no lacquer finish do not find too many ready buyers anymore. Buyers are today looking for glitter and shine…even in engravings and carvings. The market is changing fast and I will have to consider innovating”. But then cheerfully adds” however there still are a few who appreciate that not all that glitters is gold”.

Looking back into a tradition of craftsmanship going back generations National Award Winner Ashok Kumar Mohapatra, 37, speaks with pride of his craft and vocation of wood carving. Born into a family of traditional stone carvers at Basti Pathuria Sahi in the historic town of Puri (Odisha) he received his first lessons and training from his father and uncles, who in turn had learnt their consummate art from Shri Giridhari Lal Mohapatra his talented and distinguished grandfather. The Mohapatras have earned a name for excellence in stone carving, statue making and temple building. They trace their ancestry to the builders of the acclaimed temple of Lord Jagganath at Puri.

A smile of satisfaction touches Ashok Kumars face as he reminisces how as a child he enjoyed polishing stones on way to school and even at that young age earned a little money selling small images of Lord Jagganath near the beach. The excellence in his craft came later under the careful guidance of his father Madan Mohan Mohapatra who recognized in his son talent and capability to take on the family inheritance. While the older generation had mastered the craft of carving granite, sandstone and red stone Ashok Kumar made a niche for himself as an entrepreneur carving in wood. Interestingly this happened when a businessman marketing his fathers carvings suggested that he try his hand at wood as many Japanese tourists were looking for crafts in a lighter medium.

The wood’s he chose to work on are ‘pani gambhari’ a soft creamish white teak along with the harder ‘phula gambhari’ and the darker sisu or rosewood for heavier pieces, which he buys from Puri. While features in painted wood carvings are usually less defined and diffuse, those done on ‘gambhari’ are sharp and fine and attain an exquisite work finish resembling the workmanship of sculptors.

The motifs include various stylized animals and birds, elephant, lion, tiger, bull, peacock etc, Radha, Krishna and sakhis and the three most popular deities of the Puri temple, Jaganath, Balabhadra and Subhadra. The three chariots of the Puri car festival are decorated with wooden images depicting various deities as parswadevatas. A popular image is from the Mahabharata, of Krishna the sarathi or charioteer teaching Arjuna the tenets of the Gita while guiding the horses harnessed in front. Excellently proportioned and finished to fine smoothness these wood carvings depicting myths, legends and folklore are a collector’s delight. Good examples of the work of the wood carvers of Odisha can be found in temple ceilings and carved wooden beams and doors in places like Charchika temple, Buguda, Banki, Birnchinarayan temple, Kapilas, Siva temple and the Laxmi Nrusingha temple at Berhampur.

Ashok Kumar’s winning work is the ‘Buddha Kila’ a mural composed of many scenes from the life of the Buddha. A relief work composed on a single plaque of wood it has taken him two years and seven months to complete. With grace, delicacy and beauty the figures present different stages of Bhagwan Buddha’s life. The serene Buddha and his life fascinated the young Ashok Kumar. Seeing images brought to life in stone by his father brought in him a dream of some day doing the same. While many craftsmen were depicting the life stories of Gods and Goddesses of the Hindu pantheon the life of Buddha was ignored for reasons unknown. His award winning Buddha collage is culmination of single minded devotion to his art.

Ashok Kumar is happy being in Delhi to show his craft to a wider audience and to receive the National Award for Master Craftsperson’s given by the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. This exposure gives him an opportunity to reach out to a wider audience and contact more buyers. His one regret as he says is “works such as mine with an earthy character and rough texture, with no lacquer finish do not find too many ready buyers anymore. Buyers are today looking for glitter and shine…even in engravings and carvings. The market is changing fast and I will have to consider innovating”. But then cheerfully adds” however there still are a few who appreciate that not all that glitters is gold”.

A smile of satisfaction touches Ashok Kumars face as he reminisces how as a child he enjoyed polishing stones on way to school and even at that young age earned a little money selling small images of Lord Jagganath near the beach. The excellence in his craft came later under the careful guidance of his father Madan Mohan Mohapatra who recognized in his son talent and capability to take on the family inheritance. While the older generation had mastered the craft of carving granite, sandstone and red stone Ashok Kumar made a niche for himself as an entrepreneur carving in wood. Interestingly this happened when a businessman marketing his fathers carvings suggested that he try his hand at wood as many Japanese tourists were looking for crafts in a lighter medium.

The wood’s he chose to work on are ‘pani gambhari’ a soft creamish white teak along with the harder ‘phula gambhari’ and the darker sisu or rosewood for heavier pieces, which he buys from Puri. While features in painted wood carvings are usually less defined and diffuse, those done on ‘gambhari’ are sharp and fine and attain an exquisite work finish resembling the workmanship of sculptors.

The motifs include various stylized animals and birds, elephant, lion, tiger, bull, peacock etc, Radha, Krishna and sakhis and the three most popular deities of the Puri temple, Jaganath, Balabhadra and Subhadra. The three chariots of the Puri car festival are decorated with wooden images depicting various deities as parswadevatas. A popular image is from the Mahabharata, of Krishna the sarathi or charioteer teaching Arjuna the tenets of the Gita while guiding the horses harnessed in front. Excellently proportioned and finished to fine smoothness these wood carvings depicting myths, legends and folklore are a collector’s delight. Good examples of the work of the wood carvers of Odisha can be found in temple ceilings and carved wooden beams and doors in places like Charchika temple, Buguda, Banki, Birnchinarayan temple, Kapilas, Siva temple and the Laxmi Nrusingha temple at Berhampur.

Ashok Kumar’s winning work is the ‘Buddha Kila’ a mural composed of many scenes from the life of the Buddha. A relief work composed on a single plaque of wood it has taken him two years and seven months to complete. With grace, delicacy and beauty the figures present different stages of Bhagwan Buddha’s life. The serene Buddha and his life fascinated the young Ashok Kumar. Seeing images brought to life in stone by his father brought in him a dream of some day doing the same. While many craftsmen were depicting the life stories of Gods and Goddesses of the Hindu pantheon the life of Buddha was ignored for reasons unknown. His award winning Buddha collage is culmination of single minded devotion to his art.

Ashok Kumar is happy being in Delhi to show his craft to a wider audience and to receive the National Award for Master Craftsperson’s given by the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. This exposure gives him an opportunity to reach out to a wider audience and contact more buyers. His one regret as he says is “works such as mine with an earthy character and rough texture, with no lacquer finish do not find too many ready buyers anymore. Buyers are today looking for glitter and shine…even in engravings and carvings. The market is changing fast and I will have to consider innovating”. But then cheerfully adds” however there still are a few who appreciate that not all that glitters is gold”.

Wood Carving of Odisha,

Looking back into a tradition of craftsmanship going back generations National Award Winner Ashok Kumar Mohapatra, 37, speaks with pride of his craft and vocation of wood carving. Born into a family of traditional stone carvers at Basti Pathuria Sahi in the historic town of Puri (Odisha) he received his first lessons and training from his father and uncles, who in turn had learnt their consummate art from Shri Giridhari Lal Mohapatra his talented and distinguished grandfather. The Mohapatras have earned a name for excellence in stone carving, statue making and temple building. They trace their ancestry to the builders of the acclaimed temple of Lord Jagganath at Puri. A smile of satisfaction touches Ashok Kumars face as he reminisces how as a child he enjoyed polishing stones on way to school and even at that young age earned a little money selling small images of Lord Jagganath near the beach. The excellence in his craft came later under the careful guidance of his father Madan Mohan Mohapatra who recognized in his son talent and capability to take on the family inheritance. While the older generation had mastered the craft of carving granite, sandstone and red stone Ashok Kumar made a niche for himself as an entrepreneur carving in wood. Interestingly this happened when a businessman marketing his fathers carvings suggested that he try his hand at wood as many Japanese tourists were looking for crafts in a lighter medium. The wood’s he chose to work on are ‘pani gambhari’ a soft creamish white teak along with the harder ‘phula gambhari’ and the darker sisu or rosewood for heavier pieces, which he buys from Puri. While features in painted wood carvings are usually less defined and diffuse, those done on ‘gambhari’ are sharp and fine and attain an exquisite work finish resembling the workmanship of sculptors. The motifs include various stylized animals and birds, elephant, lion, tiger, bull, peacock etc, Radha, Krishna and sakhis and the three most popular deities of the Puri temple, Jaganath, Balabhadra and Subhadra. The three chariots of the Puri car festival are decorated with wooden images depicting various deities as parswadevatas. A popular image is from the Mahabharata, of Krishna the sarathi or charioteer teaching Arjuna the tenets of the Gita while guiding the horses harnessed in front. Excellently proportioned and finished to fine smoothness these wood carvings depicting myths, legends and folklore are a collector’s delight. Good examples of the work of the wood carvers of Odisha can be found in temple ceilings and carved wooden beams and doors in places like Charchika temple, Buguda, Banki, Birnchinarayan temple, Kapilas, Siva temple and the Laxmi Nrusingha temple at Berhampur. Ashok Kumar’s winning work is the ‘Buddha Kila’ a mural composed of many scenes from the life of the Buddha. A relief work composed on a single plaque of wood it has taken him two years and seven months to complete. With grace, delicacy and beauty the figures present different stages of Bhagwan Buddha’s life. The serene Buddha and his life fascinated the young Ashok Kumar. Seeing images brought to life in stone by his father brought in him a dream of some day doing the same. While many craftsmen were depicting the life stories of Gods and Goddesses of the Hindu pantheon the life of Buddha was ignored for reasons unknown. His award winning Buddha collage is culmination of single minded devotion to his art. Ashok Kumar is happy being in Delhi to show his craft to a wider audience and to receive the National Award for Master Craftsperson’s given by the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. This exposure gives him an opportunity to reach out to a wider audience and contact more buyers. His one regret as he says is “works such as mine with an earthy character and rough texture, with no lacquer finish do not find too many ready buyers anymore. Buyers are today looking for glitter and shine…even in engravings and carvings. The market is changing fast and I will have to consider innovating”. But then cheerfully adds” however there still are a few who appreciate that not all that glitters is gold”.