JOURNAL ARCHIVE

In two earlier articles readers were introduced to the Khatris of Kachchh district in Gujarat, western India. The first article described the history and development of their traditional vocation -block-printing and dyeing textiles - while the second discussed their experiences following the destruction of the Gujarat earthquake of January 2001. This article describes some of the technical processes of block-printing and the use of natural dyes. It features ajrakh, a resist-dyed cloth, colored predominantly red and blue with madder and indigo that is printed on both sides of the fabric. AJRAKH The origins of the term ajrakh remain unclear. The explanation favored by many scholars is that it derives from azrak, the Arabic for 'blue', and this would seem likely considering its indigo hue. Ajrakh is the traditional male attire of the maldharis, the Muslim animal herders of Kachchh. Highly prized for its enduring colour, it is attributed with protective properties against the district's harsh climate and is customarily given to a groom at the time of marriage. Traditionally ajrakh was printed on hand-woven cotton (khadi) made on pit looms by the Vankars (weavers). Due to the narrow width of khadi, the practice developed of joining two pieces of fabric together to make: a serviceable garment. The elaborate geometric and floral designs of ajrakh were further embellished by an embroidered centre seam, often worked in an interlacing stitch known as machi kantho (fish-bone stitch) by the women. Nowadays, the use of broad width mill cloth from the industrial belt of Gujarat has negated the need for joining the fabric, and a two-piece ajrakh is increasingly rare. Indeed, the local use of true ajrakh is in steep decline as ersatz versions - industrially printed on polyester - have taken over the home market. At about eighty rupees per piece, polyester ajrakh is a tenth of the price of the traditional cloth and it is this more than anything else that has eroded the Khatris' market. Previously, ajrakh was made throughout Kachchh, in parts of Rajasthan and Sindh province, Pakistan. The number of families still making it in Kachchh has dwindled to just two: there is a parallel decline in Rajasthan. Of the two families in Kachchh, only that of the late Mohammad Siddik at Dhamadka and Ajrakhpur still adheres to the lengthy procedure of dyeing and printing the cloth with natural colors. There is a healthy interest in block-prints and ajrakh from overseas and eighty percent of their goods are exported.

Issue #10, 2023 ISSN: 2581- 9410 By the end of the Pleistocene period (roughly 2.5 million years ago to 10,000 BC) historical references state that some of our ancestors had started using various kinds of traps, nets and snares for hunting.[1] These could have been of leather, hair, roots or natural fibres. This was also the period when man started settling down to practice agriculture. During this period, humans started using grass and wood to make their shelters in the form of tents or huts, particularly in the tropics and subtropics. Different kinds of fibres may have been discovered during this period. Flex, linen and hemp are believed to be the earliest cellulose plant fibres used for spinning and weaving for production of textiles and have been found across various excavated historical sites in India, China and Egypt. These were followed by cotton and silk (4500 BC to 2640 BC).[2] In Europe, the Swiss Lake Dwellers cultivated flax and wove linen into fabrics as early as 8000 BC.[3] These facts ascertain that people had the skill to extract fibre from plants at the very beginning of settled life. Apart from textiles, man used various fibres available from the local vegetation for agricultural use, housing, transportation and hunting. The wandering tribes moving across the forests and deserts also relied on material available in their immediate environment. For example the Rathwa Bhil Adivasi in eastern Gujarat still use Toddy Palm tree (Borassus flabellifer) leaf stalks to make twisted cords and strings for their hutments. Gond Adivasi in Madhya Pradesh use the roots of the Kesula (Butea monosperma) tree to extract fine fibre for tying their crop harvest like wheat and tendu leaf bundles, while the snake-charmer Kalbelia nomadic community in the desert of western Rajasthan use Akara (Calotropis procera)[4] plant stem fibre to make knotted sacks called Guna for carrying their clothes, quilts, utensils and babies on donkey back. The agriculturists in the same region use the Akara fibre for making slings called ‘Taant’ to make a whip cracking sound to frighten away birds eating their ripened crops. This is a most traditional and humane way of protecting the fields without harming any creature. The location featured in this article is ethno-geographically called Dhat and falls in parts of Barmer and Jallore, i.e. western districts of Rajasthan, and in neighbouring Pakistan. Akara grows on sand dunes, barren lands as well as on the semi-arid cultivated land. Locally in Dhati language the plant is called Akwala (deriving its name from Akara or Aak). Akara yields fine filaments of fibrous silky cotton from its ripe flower pods, which has various uses in the Tropics ranging from stuffing pillows to making skull caps. It is a natural cellulosic stem fibre and is said to have high tensile and abrasive strength, but is not preferred for textiles due to its heavier weight than cotton fibres[5] or wool. Akara has a small staple length, high percentage of small uneven fibres and is difficult to twist making it unfit for fine spinning of yarn. But a few research experiments have indicated that a good quality cloth could be prepared from Akara yarn if its evenness and fineness could be improved. Chemical experiments to improve the percentage of fibre recovered have resulted in success but industrial production has never been attempted. Appropriate technology could be used to improve the cleaning and beating of the fibre to make a more efficient and cost effective production method that could be scaled up. It should be noted that rope making in these regions of India is a gender specific job and the entire process from beginning to end is done by men. Like Akara, various grasses and shrubs are also used for making sturdy ropes meant for drawing water or making thatched huts in Rajasthan but, Akara is the preferred fibre because it is soft and freely available in abundance throughout the year. The fresh leaves of this plant serve as fodder for goats and camels in the desert, while the stems are used for making the underlying frame structure of the thatched huts and also serve as a source of fuel for cooking food. References to the toxicity of the plant in western sources are misleading. People have associated deserts with scarcity, but here people have found sustainability with available material in their surroundings. People value this plant highly and there are particular seasons and cycles when it is cut, collected, stored and used. For extraction of the Akara fibre, the selection of plants is an important criterion - only 6-8 month old stems are used. Thin, smooth, straight and node-less stems are cut just before the monsoon (May-June) leaving the main stalk of the plant intact.[6] The cutting of the Akara plants before the monsoon also heralds the time for ploughing of the fields and sowing of millet and pulses. These sticks are then stored carefully on raised ground without touching the sand to save them from termite attack during the monsoon when air moisture content is high. In Rajasthan there is also the danger of locust attacks in which case the Akara leaves and soft outer stems are eaten killing the plants. Unlike other places (like in Indonesia) where the stem fibre from this plant is separated by retting, in the desert this method cannot be applied due to the scarcity of water. Thus the plant is cut, collected and stored before the monsoon to allow rainfall on it. Each stem could be 15 feet long depending on the growth of the plant. The scanty rain drops of the desert loosen the fibre from the stem of Akara which is then removed in layers by peeling it from the outer surface of the stem. To remove the fibre the stem is broken from the thicker end to get access to the strands. These strands are peeled off carefully by further breaking the stem into portions of 9-12 inches successively. One to three feet length strands are collected depending on the quality of the stems. These strands break wherever there are leaf joints or nodes on the stem. Thus the stem has to be broken to pick up the strands again and again. The peeled strands are collected, fastened together, twisted and doubled to form a hank (Goti) and then beaten with a wooden stick by placing it over a wooden plank to remove the dirt and loose material. It is then opened and shaken to loosen the dirt. This process of making the hank and beating it is done two to three times which finally yields a softer fibre nearing to cotton quality. The colour also changes from greyish to white. The fibre is then spun clockwise into yarn with the help of a basic wooden tool called Dheri (spindle) made of Kumatiya tree (Senegalia senegal) wood. The yarn is then double plied to form a loose cord. It is dipped in water in a pot and left for one to two days (at least 24 Hrs.). Water absorbs all the alkalinity and dissolves the lignin in the fibre. It is then taken out and washed thoroughly for further removal of the finer dirt. This makes it very soft. It is dried and the second round of spinning takes place with the spindle which produces a strong cord. On completion the cord it is held up in one hand and squeezed inside a cotton cloth by the other using one directional strokes. This abrasive action of the cloth makes it further smooth and shiny removing any traces of dust or extra fibre left on it. It could be further plied to make a rope but generally two ply cords are used for general purposes. Akwala cord is mainly used for making cots (charpai)[7] and ropes for cattle by the villagers. A cot made of Akwala can last for 40 years if taken care of properly and repaired regularly whenever the cord breaks.[8] Unlike plastic it doesn’t become brittle when exposed to the sun and heat of the desert. People in the desert still prefer to use traditional fibres obtained from plants like Akara, Seeniya (Cassia augustiflora), Kheemp (Leptadenia pyrotechnica) and grasses which grow in the surroundings. Recently they have also started using cords made out of recycled cloth shreds which come from textile industries in Balotra, Pali and Jodhpur. It is an interesting fact, however, that people in the desert still prefer Akara cords and ropes for their household use due to its durability over plastic and jute. The raw material is freely available in the surroundings, thus it costs nothing. This is the most popular fibre of the desert due to its cotton like quality unlike any other natural fibres available locally. With investment and research into improving the processes the production of Akara fibre could provide livelihoods. With changing attitudes to gender specific jobs daughters and wives could be involved in collecting and other processes thus improving the lives of both men and women in the Dhat regions and in keeping alive a sustainable but dying craft. Akara has hope for the desert and also the environment.

|

|

| Illustration of Akara Plant by Waseem. © Kaner collection | Sack made by the nomadic Kalbelia community used for keeping quilts and household items. The cord has been dyed with natural red ochre. Barmer, Rajasthan. |

|

|

| Cot made with Akara stem cord dyed in red. |

| Process of extraction of Akara yarn and preparation of plied cord out of it. Demonstrated by Mahesh Singh Rathore, village Agenshah-ki-Dhani, Barmer, Rajasthan. | |

| 1 Cutting side branches of the Akara plant 2 Collection of the useful stems 3-5 Peeling of the fibre strands 6. Collected fibre 7 Hank of the loose fibre 8 Beating the fibre with wooden stump 9 Cleaning the fibre by loosening and opening | 10 Spinning of yarn 11 Double plying the yarn 12 Spinning of cord 13 Hank of double ply cord 14 Washing of the cord 15 Spinning of the washed cord 16 Rubbing and squeezing the cord with cloth piece 17 Bundle (deriya) of Ankara cord |

Globally, women and men are learning to bridge social, cultural and economic divides to find ways for their communities to survive and be sustainable. In Asia, Africa, Latin America and elsewhere, local economies are being strengthened through development of community enterprises. As a consequence, livelihoods and local cultural practices are being transformed. This article is based on research in Thailand, in which I investigated different approaches and common concerns of community organizations that work with rural artisans to ensure economic and cultural survival. The article profiles the role of the Northeastern Handicraft and Women’s Development Network (NWD) in encouraging and facilitating community businesses among women who are weavers in rural Northeast Thailand.Global economic forces have increased the number of people living in poverty and undermined traditional ways of life and livelihoods in rural villages of Northeast Thailand. A crisis of social, cultural and environmental degradation has prompted a search for solutions at the local level. Solutions, emerging in rural areas, are shaping alternative models of development by drawing on the resilience of the people and the relevance of their traditional skills and knowledge. The Northeastern Handicraft and Women’s Development Network plays a significant role in facilitating this process in Thailand. In the context of rural Thailand, alternative entrepreneurship is a socio-economic strategy of organizing, educating and empowering people to work collectively at the village level to strengthen their capacities to create sustainable livelihoods in their own communities. In particular, rural women weavers are learning to work together to build organizations that serve their needs and concerns for income and social security, health, safety and environmental protection. As a means of employment, alternative entrepreneurship promotes collective responsibility and involvement in management and marketing. As a forum for integrating new knowledge with local wisdom, alternative entrepreneurship fosters appropriate technology and environmentally sustainable practices. And as a counterforce to the devaluation of traditional rural ways of life, alternative enterprises are people’s organizations concerned with preserving cultural heritage. My purpose in this article is to focus on a number of the complex issues involved in creating and sustaining artisan enterprises in rural Thailand. RURAL ECONOMY AND THE CRAFTS SECTOR Globalization and the 1997 Asian economic crisis have profoundly affected the lives of millions in Asia. Poverty is severe in rural Thailand, especially in the North and Northeast regions, where people did not benefit from Thailand’s economic boom years. Rather, they became victims of environmental destruction, industrialization, marginalization and displacement as a direct result of the dominant development model promoted in the West and embraced by the Thai government in the 1970s, 80s and early 90s (Laird, 2000). Among the rural poor are artisans, many of whom are moving away from traditional livelihoods. Lack of access to raw materials and to markets, exploitation by middlemen, low prices for long hours of work, and the devaluing of rural ways of life, keep wages at poverty level and undermine the sustainability of artisan communities. In rural Northeast Thailand, known as Isaan, the majority of people are farmers who grow glutinous and white rice, cassava, sugar cane, maize, fruits, vegetables and jute. The region is considered the poorest in the country because of extreme temperatures, poor soil, and alternating droughts and floods. Despite harsh conditions, in the past Isaan farmers were able to adapt to their environment and they were self-reliant as a family unit, producing all their basic needs. Isaan women, known to be industrious, did household chores, worked in fields during planting and harvesting, cultivated cotton and mulberry plants, made household wares from clay and wove cotton and silk cloth. The women worked so their brothers could go to school, become monks or pursue higher education in cities. As self-reliant agriculture and ways of life have disappeared, rural debt in Thailand has soared (estimated at 100 billion baht or $4 billion US). Nearly every household needs money to buy rice, other food, medicine, household goods and clothes, most of which come from outside the village. Farmers borrow from the agriculture bank for items such as fertilizer and small tractors. Each year they try to earn a living from farm labour and grow enough to make a profit but the price for agricultural products is very low and they can’t cut the cycle of debt. After the four months of agricultural season men used to go outside the village to look for work in construction, in factories or as taxi drivers. However, since 1997, there has been no more work in construction or factories. Women stay home and do sub-contract homework, sometimes sewing school uniforms. But the wages are very low. Up to 85% of Isaan villagers earn less than they need to survive. (WAYANG, 1995, pp. 21-23) The crafts sector is a significant arena of rural non-farm employment, but it is largely neglected in national policies and development agendas. Increasingly, different levels of government and institutions such as the ILO recognize the importance of women’s home-basedwork in rural areas and their needs for education and training (Saeng-Ging, 2000). Craft activity fits the category of home-based work and for many women it is a primary source of income that contributes to the economic viability of their families and communities. Craft - redefined as an economic and development activity - has great potential to become a means of sustainable livelihood, particularly among women in rural areas who can use their traditional skills to become wage earners, manage small businesses, and take on leadership roles in their communities. Weaving has traditionally been a significant activity for Thai women. Weaving is part of the indigenous or local "science and technology" developed and handed down by women through generations. In traditional Isaan society, both the weaving process itself and the cloth produced were integral to their social, cultural and economic life. From birth to death, from individual to family to community, from secular to religious rites, woven materials were used (Conway, 1992). For Isaan women, weaving was not only a household duty; it was a way of gaining respect in this life and spiritual merit in the next. With the destruction of village ways of life, traditional weaving lost much of its importance and value and disappeared in some areas. This situation began to change, however, with the work of NGOs in the region that encouraged rural villagers to value their local knowledge and cultural heritage. Women began to organize themselves to participate in decision-making and contribute to community development. And traditional weaving became revitalized in the context of community enterprise development. Now, women use income from weaving to pay for their children to go to school and also to help relieve the family’s agricultural debt.

NORTHEASTERN HANDICRAFT AND WOMEN'S DEVELOPMENT NETWORK

The Northeastern Handicraft and Women’s Development Network (NWD) was established in 1991 as a working committee under the NGO Coordinating Committee on Rural Development of the Northeast. The objectives were to: campaign on the importance of women's development among NGOs in the Northeast; establish a sustainable economic and marketing base for the Network; upgrade the knowledge, capacity and potential of rural women in the Northeast; and, promote the establishment of social services at the community level (NWD). Since its inception, NWD worked in areas of women’s health, education, and empowerment. Four founding member NGOs focused on handicraft development, drawing on the traditional weaving skills of village women to help preserve the crafts of the region. During 1994-5, NWD provided management and business skills training to support the development of community enterprises that were owned and run by the village weaving groups. By the year 2000, NWD represented thirty member organizations working with three thousand families in eight provinces of the Northeast. Twelve of the thirty member organizations are involved with natural resource management, sustainable agriculture, women’s rights and women’s homework; eighteen focus on handicraft and business development. Currently, the ILO and HomeNet, an international network of home-based workers, support NWD. (Saeng-Ging, 2000). The director of NWD is Suntharee Saeng-Ging, a community activist and administrator with a political science degree from University in Bangkok. Suntharee moved to the Northeast in 1990 to do community work in a village 100 km. from Khon Kaen. She worked many years helping women in the community to organize and start a local weaving group. In May 2000, I recorded a conversation with Suntharee at the Mae Ying Handicraft Shop in Khon Kaen where the NWD office is located. Following are issues that arose during our conversation, issues that concern NWD and the women involved in the weaving groups.WEAVING GROUPS

Panmai and Prae Pan are two highly active member organizations of NWD. They are large well- established weaving groups, known for their high quality woven products that sell in Bangkok and abroad. Panmai traces its origins to the 1985 initiative of the Appropriate Technology Association of Thailand, called the Local Weaving Development Project. Women’s lack of education, economic status, access to resources, and decision-making power were the impetus to develop a network of small businesses to work towards empowerment of rural women. In early stages of developing “alternative entrepreneurship” both Panmai and Prae Pan received strong support from NGOs for developing women’s leadership and managerial skills, as well as design training and contacting markets WAYANG, 1995). Other NWD member organizations are much smaller weaving groups that do not have the benefit of NGO support and funding for training and marketing. It takes almost ten years to establish a viable organization in the villages where the aim is to have the group work cooperatively. Rather than having weavers sell their work individually, prices are set and the work is sold as a group. Large groups that receive external funding can pay weavers for their work before it is sold. The weavers receive their wages monthly. For example, in Panmai and Prae Pan every piece that reaches a standard of quality set by the group is purchased from the weaver, and then the organization tries to sell the woven products. In contrast, small groups without funding cannot pay the weavers until the group sells the products. This often takes a long time or the goods may not sell at all and the weavers are not paid. The inability to pay outright for the weaving has a negative impact on the small groups and many of them have had to stop the weaving.NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

The availability of good quality raw materials for craft production is an essential ingredient of artisan enterprises. The transformation of cotton and silk fibres into thread, which occurs at an early stage of the production chain, is a precursor to the weaving process. Hand spinning is labour intensive, but factory produced thread is often imported. In addition, alternative enterprises, concerned about environmental impacts and eco-friendly products need to consider where and in what manner the cotton is grown and the silk reared. While the lives of Isaan women were traditionally interwoven with the art of silkworm rearing and local agriculture produced cotton fibre, recent economic and environmental factors impinge on access to raw materials and decisions about local production of thread. In the early 1990s, when the weaving groups were selling their products well, the weavers stopped producing silk and cotton thread themselves because they wanted to use their time for weaving instead of spinning. At first they bought thread from neighbours, then from local markets, and then from Laos and China even though they knew the quality of the thread they bought was very different from the quality they could make themselves. Now, they do not know, and they are concerned about, whether the imported cotton is organic, or whether pesticides, insecticides, or genetically modified seeds have been used in growing the cotton. Climate change and environmental degradation have increased the difficulties of growing cotton locally, raising silkworms and growing indigo, a traditional dye plant. The availability of water and quality of the soil has deteriorated to the extent that farmers cannot grow enough cotton to produce enough thread to be used in weaving. Only 10% of the cotton thread used in the Northeast comes from the farmers’ fields. Indigo, a plant traditionally used in the dyeing cotton and silk threads, is very sensitive to climatic conditions and the area conducive to growing indigo has become very limited. Indigo grows well in forest shade and needs a lot of rain at a particular stage of growth. However, forests have diminished, the climate is too hot and dry, and the rains come at unusual times. Indigo is sometimes grown in rice fields after the rice harvest when there is rain. But if the rain comes too early or there is too much rain the indigo plants die. NWD has started to encourage weavers to produce their own thread again. Even though growing and spinning cotton, looking after silkworms, and growing indigo each involves difficult time- consuming processes, and it is almost ten years since the women stopped producing cotton and silk thread, the weavers are beginning to agree that they need to produce the thread themselves once again. They realize they cannot control the price or quality of imported cotton and silk thread. The cost of cotton thread keeps rising and the weavers cannot always get good quality. However, Suntharee said, it will be a difficult slow transition for weavers to return to producing their own thread. If they have the choice, they would rather weave; they can earn more money from weaving than from spinning.Environment and Health Protection

Many NWD member organizations focus on weaving and business development, but an objective of the Network is to raise awareness through seminars and other activities about a range of issues that impact the lives of women. Panmai and Prae Pan, for example, began by developing the weaving groups, but when they became strong enough, NWD encouraged them to think about how to conserve their local environment. They tell the weavers that they must look after the environment or else they will no longer be able to do natural dyeing or grow cotton in the future. In the past, weavers used natural dyes from the bark, leaves or fruit of different plants. Their methods for achieving yellows, browns, blues, greens, reds and black were perfected and handed down through generations to give a distinctive character to Isaan fabrics. But natural dyeing takes a long time and hard work and many weavers changed to chemical dyes. These are easier to use, but they create pollution and health problems. Especially in dyeing silk, a variety of toxic chemicals are used to produce a shine or to whiten certain threads in a resist dye process. The chemical toxicity pollutes the land and water close to the women’s homes. How to solve the pollution problems of chemical dyeing is a key issue being raised by the weaving groups. When dyes are brought into the villages, there is no information about how to use them or how to protect dyers from the dangers of using these chemicals. Suntharee said that the dyes come in plastic bags that only say, “This is for shiny”, or, “This is for washing colour”. Dyers get serious nose and eye problems from working with the chemicals, which smell bad and make the eyes sting and run. Even the weavers who use the chemical-dyed threads put a cloth over their faces and wear eyeglasses to protect their lungs and eyes. As well as looking for ways to introduce non-toxic chemical dye colours, NWD has a program to train home workers about the dangers of toxic chemicals used in their work. NWD worked with the Health Ministry and the ILO to prepare a training program to teach about health risks, safety and protection in the use of chemicals. They have prepared a handbook that can be used in other groups that have not received this training.Education and Training in Product Development

NGOs within the Network worked many years on the social and political issues of organizing women’s groups. When they began to establish community businesses, they faced problems related to a lack of expertise in business management. Over a ten-year period they solved many problems by acquiring experience and skills in management and administration. Currently, NGOs have a lack of knowledge about product design and marketing and they want consultants in product development to help the weaving groups. Although many design consultants work with private enterprises, there are only two or three in Thailand who work with NGOs on product design and marketing. Sometimes specialists from the university or business sector in Khon Kaen provide design training. Somyot Sapupornhemint, based in Bangkok, is an active consultant with NGOs. One of the original people who worked on establishing the Handicraft Centre in Northeast Thailand, Somyot is an advocate for organic farming and the preservation of craft skills in Thailand. He has written a handbook on product development, pricing and marketing for Thai NGOs and he gives workshops and advice to weavers groups, including cotton spinning and natural dyeing with indigo. Weaving groups need training in fabric design and colour and also tailoring, sewing and finishing. Value is added to their work when they make cloth into skirts and shirts and it is easier to sell products, such as, bedspreads, tablecloths and place mats rather than lengths of fabric. However, it is very difficult for the weaving groups to learn about modern urban lifestyles in order to design and make appropriate products. They do not know, for example, the size of the bed or the proportions of pillows for the urban market. Suntharee said they have to learn the right size to make things such as skirts and scarves, to avoid the problem of making something that is “too small to be a shawl, too big to be a scarf.” In addition, the groups cannot follow fashion design and colour trends because these change too quickly. There is too much for them to learn all at once. Marketing Since the 1997 economic crisis in Asia all the weaving groups have suffered from a drop in sales. This has been harder for the smaller groups than for Panmai and Prae Pan. However, each weaving organization is concerned about finding ways to improve their products and increase their access to markets. In the last few years NWD has initiated discussions among the weaving groups about the need to raise the quality of their products. They have also discussed how to make their products “more organic” because they know that more consumers in the world are becoming concerned about the environment. NWD is trying to reach a very specific market – people who understand social and environmental concerns and want to buy natural products. In general, cotton is sold more readily than silk, which is more difficult and costly to make in good quality. However, few Thai buy natural dyed products; they like bright colours that come from chemical dyes. NWD tries to increase consumer awareness of the environmental and health risks associated with chemical dyeing by disseminating information through newspapers, magazines or exhibitions. The younger generation, mainly university students, has a better understanding of these issues but their income is low, which means they cannot support the groups by buying NWD products. Marketing is a key issue for the weaving groups and it is especially difficult for small groups that do not have external funding to support training in product development and marketing. NWD has offered training programs to help member organizations with marketing and, since 1997, NWD has operated the Mae Ying Handicraft Shop in Khon Kaen where woven products are for sale and business management workshops are offered. However, the three years since they opened the shop have been the years of the economic crisis and a decrease in sales. NWD also tries to organize exhibitions for the weaving groups. Many times each year NWD sends their colleagues and products to Bangkok where there are more people who understand and support the work of rural community enterprises. Sometimes the Thai government or NGOs organize trade fairs or seminars and NWD participates. For example, in 1999 the Australian Embassy organized an exhibition for NGOs that they support and members of NWD went to Bangkok for the exhibition. However, taking part in this event was expensive, and NWD did not make enough money to cover the costs. A small number of the NWD weaving organizations, including Panmai and Prae Pan, participate in Thai Craft Fairs in Bangkok, which draw a large number of urban Thai, ex-patriots and foreigners. More than sixty craft producer groups from all regions of Thailand are represented at each ThaiCraft Fair. However, it is difficult for the smaller member organizations of NWD to go to ThaiCraft Fairs. First of all, ThaiCraft has a high standard for quality. Secondly, NWD cannot contact or participate in ThaiCraft on behalf of the weavers groups since ThaiCraft asks the groups to contact them directly. And thirdly, ThaiCraft wants members of the groups to come to Bangkok to sell their crafts themselves rather than send their products. However, going to Bangkok is more expensive than sending their goods and so only the large groups can take their products to ThaiCraft and make a profit. The large groups, such as Panmai and Prae Pan have overseas customers through the work of NGOs who contact Fair Trade Organizations. However, sales through Fair Trade Organizations are low because the woven products don’t change often enough. Some weaving groups have made the same designs for ten years and customers who bought items previously want to buy something new. Fair Trade Organizations ask for new designs but the weaving groups are not able to change their products quickly. It takes a long time to come up with original design ideas, communicate with the weavers about the new products, and make enough to supply the market. Strengthening the Network HomeNet , initiated in 1995 with the support of the ILO Rural Home Workers Project, has played an important role in campaigning internationally for policies that give security of work, wages or welfare to home-based workers. These are new issues in Thailand where there is no law to protect home workers. In 1998, HomeNet Thailand was set up as an NGO to coordinate a network of 89 home-based workers organizations in the North, Northeast and Bangkok municipality (Saen-Ging, 2000). The main funding for NWD - 50% from ILO and 50% from HomeNet - covers the costs of administration, building rental, electricity and telephone, and salaries for the director and a secretary. There is no ongoing financial support for programs for the weaving groups; the ILO funds only activities for home workers in the sub-contracting system. When groups in the Network ask for help to improve the quality of their products, for example, NWD tries to provide design training for both small and large groups. And every time they plan a training session, NWD has to make funding proposals to different organizations. If they receive the funding they can give a workshop, if not, they have to wait. Otherwise NWD has to ask the people to pay and only the large groups can pay. One sponsor for NWD training programs has been the Canada Fund, operated by the Canadian Embassy in Bangkok, which has a focus on women and has supported many NGO programs in Northeast Thailand. NWD is doing research on home workers in the seventeen provinces of the Northeast region to gain information about what kind of work they do. With support from the Science ministry, they are also conducting a survey of handicraft groups to find out about community-based techniques used in handicraft processes, group management and marketing. They are also inquiring about the problems craft groups have. NWD hopes that the government will use the information from this survey and make plans to support people to deal with problems of funding, designing and marketing, NWD encourages women to participate on committees in village and district organizations. Suntharee said that it is not enough for women to become strong in their own weaving groups; women have to share and participate at other decision-making levels. If they want to receive funds to support weaving they have to go through the decision making process in the district organizations. If the women are happy only to be in the local women’s group, and they don’t share and participate in the other organizations, they cannot reach the government funding. “So nearly all of our women are realizing they have to learn more and participate in higher levels of the network, not only the weaving groups.” Summary Reflection NWD works on a wide range of issues that impact women by providing a forum for discussion and initiatives for their support. In this article I have focused on issues that concern the weaving groups in particular, which are challenged to develop skills in management, ideas for design and product development and relevant strategies for marketing. Critical issues confronting the weavers also include the state of the local environment, availability of raw materials and risks from toxic chemicals. To address any of these concerns requires access to information, training and education. The development of community enterprises that utilize women’s traditional skills and aesthetics of weaving is not only providing income for families in the Northeast but also strengthening women’s confidence in their ability to learn and contribute to their communities. However, external funding for training and marketing support is needed to continue to establish a base for sustainable livelihoods within the existing weaving groups and within other village groups that want to join the Network. It is a sad irony that rural women who have been marginalized by the impact of the Western macro-economic development model require the financial support of national and international agencies and organizations that previously neglected them. Artisan enterprises are part of the informal economy, a sector of the globalizing economy that is rapidly expanding as a major source of employment, particularly for women in developing countries. For example, nearly 75% of manufacturing work in Southeast Asia is within the informal sector where women are home-based workers in the garment and electronic industries. As globalization has led to increased inequality within and between countries, a global movement has emerged in the past two decades to promote better programmes, policy and research in support of income and social security for women workers in the informal sector. The work of Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), founded 1972 in India, has been an impetus for recent international networks such as HomeNet, an international federation of home- based workers, and WEIGO -- Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing. (WEIGO, 2001. See also Lund & Srinivas) Although there are similar concerns among workers in the informal sector, artisans have unique challenges. And the difficulty of their situation needs to be appreciated as they seek to bridge the gap between rural village ways of life and the urban global marketplace in order to sell their products. As globalization promotes cultural homogenization, artisans have an important role in protecting cultural diversity, such as the example of women weavers in Northeast Thailand who are reclaiming the value of local production of handwoven textiles that bears the mark of ages- old indigenous traditions. In addition, international alternative trading organizations and fair trade networks are promoting consumer awareness of artisan products and the search for sustainable livelihoods in rural areas. Further research into community enterprises based on artisan skills and products will bring greater insight into development alternatives that are appropriate and sustainable; there is much more to learn about how people and cultural practices in rural areas can thrive as well as survive. References Conway, S. (1992). Thai Textiles. London: British Museum Press. Laird, J. (2000). Money Politics, Globalisation, and Crisis: The Case of Thailand. Singapore: Graham Brash Pte. Ltd. Local Weaving Development Project (WAYANG). (1995). Weaving for Alternatives. Thailand: Nutcha Publishing Co. Ltd. Jongeward, C. (2001). Prae Pan: Many Kinds of Fabrics. HomeNet, No. 15, January 2001. Lund, F. and Srinivas, S. (2000). Learning from Experience: A Gendered Approach to Social Protection for Workers in the Informal Economy. Geneva: ILO NWD. Women in Northeastern Thailand and their Participation in Community and Social Development.Brochure. (No date available). Saeng-Ging, S. (2000). Experiences in Community-based Skill Development of the Northeastern Women’s Development Network (HomeNet Northeast). Paper presented at ILO/APSDEP/TESDA Skill Development Workshop on Rural Employment Promotion for Women. Manila, Philippines, May 15-19, 2000. WIEGO.(2001). Women in the Informal Economy. Brochure End Notes While researching issues of artisan organizations in Thailand, I conversed with English speaking Thai people and ex-patriots working in Thailand. This article focuses on issues of weavers’ groups in Northeast Thailand and I am grateful to those who have informed this work, including: the director of NWD; 3 Thai rural development consultants involved in organizing weavers and developing artisan enterprises, 4 Isaan women weavers/managers of Prae Pan. (For an account of Prae Pan, see also Jongeward, 2001.) The book, Weaving for Alternatives, has been an important resource. My use of the term “alternative entrepreneurship” derives from this publication, which gives voice to the staff and women weavers involved in the Local Weaving Development Project that evolved into the community enterprise known as Panmai. This article was first published in Convergence, Volume 34(1), a publication of the International Council for Adult Education.|

It has now been a little over a year since I returned from India and started writing Postmark America. I remember the sensation I felt last year as fall set in and I was embraced by the warmth, tradition and spirit of autumn in America's Northeast. During this time of year people often pause to reminisce about their family and cultural traditions. They spend more time than usual decorating their houses with handmade crafts and take the time to enjoy a slower paced life. With this in mind, I embarked on an investigation of American folk art thinking that I would come across meticulously crafted quilts and craved wooden furniture representative early America. Instead, I found a kinship of folk artists very much in tune with the contemporary world, as well as an audience eager to be engaged by these creative masters. But what surprised me most was the depth and variety of art being created and of philosophies on what makes something folk art or someone a folk artist. To start with the most traditional representation of folk art, I did a little research on the American Folk Art Museum, located in the heart of cosmopolitan America: New York. Even this stronghold of traditional folk art displays pieces that vary from the norm. Their newest permanent exhibit, Folk Art Revealed, covers a wide array of folk art that was made throughout the eighteenth, ninetieth and twentieth centuries, with even a few pieces from our current age. The exhibit revolved around four themes that are found in all pieces of folk art throughout the centuries and relate to both conventional and unconventional manners of expression. The themes of symbolism, utility, individuality and community frame this exhibit in a way that allows comparison between objects as diverse as a mid-19th century Tooth trade sign and a 20th century piece titled Les Amis, that uses Masonic and Haitian cultural symbols to express the hope of growing positive interactions between Haiti and the US. The categories also highlight that folk art, although traditionally the beautification of utilitarian items, often has a deeper impact with its social commentary and individual expression. Pieces like Jessie Telfair's "Freedom Quilt" resonate a societal issue and speak for both the artist's individual struggle as well as a battle an entire community is fighting. The quilt depicts only the word "freedom" in bold, block letters and reference Jessie's plight to register to vote as black women in the South in the 1960s. Although the American Folk Art Museum has an extensive collection of folk art, it doesn't represent the entire gamut of American creativity. Much folk art can be described as being made by self-taught artists whose creativity is expression based and often a little bizarre. Take for example Jeff D. McKissack's "The Orange Show", a handmade personal space in Houston, Texas. Built over 25 years and now maintained by a foundation dedicated to the site,"The Orange Show" is a "folk art shrine" that consists of a series of structures which coverstwo city lots. Constructed from found objects and raw material like "old wheels, ceramic tiles, various bric-a-brac and discards", the epic work pays homage to McKissack's favorite fruit: the orange. At its opening in 1979, "The Orange Show" didn't draw many visitors which some people say ultimately caused McKissack to die of a broken heart. However, the site is now managed by The Orange Show Foundation which hosts tours, workshops and educational programs focused on Houston's cultural life. Houston is also home to other oddities in American folk art like the Beer Can House, created by John Milkovisch, as well as Cleveland Turner's "The Flower Man's Garden". Although the Intent Statement for Design Education is a massive step for the progress of Indian design education and implementation there seemed to me a point that was overlooked, put aside or at least just not directly addressed. The need for practical based experience for design students hovered just below the surface of the intent statement and was never clearly stated as necessary, important or eventual. For students coming from the top institutes in India, their designs are instilled with creativity, innovation and genius but can often fail in the market due to their impracticality or distance from market demands. These amazing sites, as well as the in-depth exhibit at the American Folk Art Museum, opened my eyes to the diversity of folk art that is still alive in America. It is always reassuring to realize that the holders of our cultural heritage and the cultivators of American creativity have not been overcome modernization but rather manipulated it to their own advantage. As nations the world over deal with globalization and a loss of traditions, these artists can stand testament to the fact that creativity cannot be homogenized. More information about the American Folk Art Museum and the exhibit Folk Art Revealed can be found at http:/www.folkartmuseum.org/. To learn more about "The Orange Show" and "The Beer Can House" visit http:/www.orangeshow.org/. |

The proceedings of the 1995 conference on the Tharu. The Meyer’s chapter gives an overview of Tharu wall art and architecture, with color photographs.

- “Who are the Tharu, National Minority and Identity as Manifested in Housing Forms and Practices?” In Harald O. Skar, ed., Nepal: Tharu and Tarai Neighbors. (Proceedings of the 1995 Conference on the Tharu, Oslo.) Bibliotheca Himalayica, Series III, v. 16. Kathmandu: EMR, 1999.

- The Myer’s documented one Tharu village’s song/dance version of the Mahabharata, last held in 1998, with a documentary video and with a translation of the song-poems into English:

- The Mahabharata: Tharu Barka Naach, documentary video. Producers; director: Deependra Gauchan. A Tharu rural version of the Mahabharata, performed in 1998 by the farmers of Dang Valley, Nepal. [Available at Insight Media under “Barka Naach” http:/www.insight-media.com/IMGroupDispl.asp. ], 1999

- Mahabharata: the Barka Naach, a rural folk art version told by the Dangaura Tharu people of Jalaura, Dang Valley, Nepal. Editors/publishers. A translation of the song-poems of this local Tharu interpretation of the Mahabharata. Kathmandu: Himal Press, 1999

- The Meyers contributed the Nepali element to the book and museum exhibit at the University of California/Los Angeles documenting rice-related artistic uses/themes in ten Asian countries. Their work focused on the Tharu granary. This is the 540 page catalogue for the exhibit, a rich documentation in writing and photography:

- “The Granary of the Tharu of Nepal.” In Roy W. Hamilton, ed., The Art of Rice: Spirit and Sustenance in Asia. The catalogue for the exhibit of the same name, to which the Meyers contributed the Nepal element. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 2003

- 3 articles, illustrated with photos, in Shangrila Magazine.

- “Ethnic Color: People of the Eastern Tarai.” Meyer + Meyer. Article and photographs. Kathmandu: Shangri-la Magazine, Vol. 7 no. 3, 1996

- “Tihar in the Tarai.” Meyer + Meyer. Article and photographs. Kathmandu: Shangri-la Magazine. Vol. 7 No. 4. , 1996

- “On the Home Front: House decorations in the Tarai.” Meyer + Meyer. Article and photographs. Kathmandu: Shangrila Magazine. Vol. 7 No. 1., 1996

- Tharu history. The history of the Tharu in the Tarai as revealed through the facsimiles of the original legal documents of grants from the kings of Nepal to Tharu over two and a half centuries. published in both Nepali and English versions.

- The Kings of Nepal and the Tharu of the Tarai: Facsimiles of Royal Land Grant Documents issued from 1726-1971. Editors/publishers/contributors. The history of the role of the Tharu in developing Nepal’s Tarai lowlands is shown through the translation, explanation and full-color facsimile images of 50 old royal documents. Kathmandu: Rusca Press and the Center for Nepal and Asian Studies, Tribhuvan University, 2000

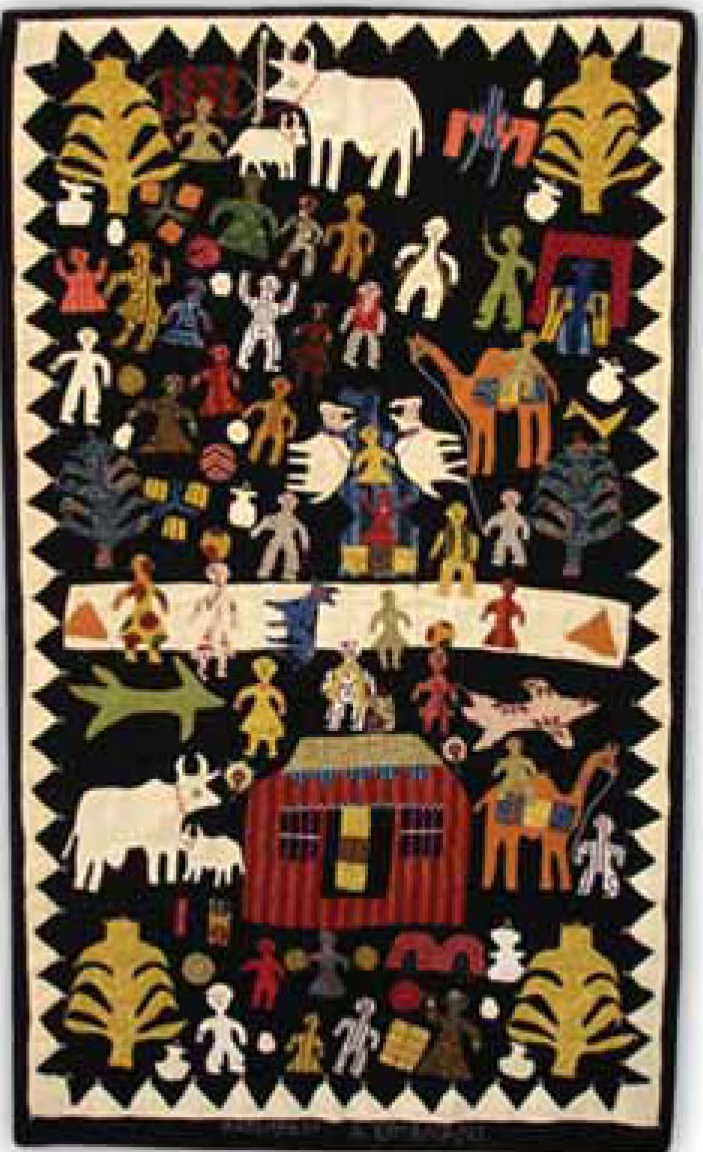

The harvest festival of Chherta held in the lunar month of Pus that falls in end–December is celebrated on the night of the full-moon. In Chhattisgarh women of the Rajwar agriculturalist community celebrate the event through creating Bhitti Chitras – the sculpted and painted clay relief figures. Decorating their homes for these festivities with reliefs of gods and goddesses, birds, animals, plants, trees and human forms the figures created vibrantly crowd their homes to bring the interiors and exteriors to life. Vividly painted in shades of orange, red, blue, green, yellow with the features delineated in black the reliefs are set against a stark contrasting white clay surface. From the walls of their homes, on storage spaces, doors, alcoves and additionally free standing bamboo screen structures these 3D images created are renewed each year with new figures added on. Living in mud homes the women apply a lipai/coating of wet clay mixed with cow dung on the floors and walls that is then covered with white Multani Mitti/ Fullers Earth. This forms the base of the work. While a variety of surfaces are covered, lattice bamboo fretwork structures are also constructed to form standalone artworks that are decorated with figures. The images are moulded into shape inspired by the makers’ imagination. Rice husk waste forms the base that is coated and shaped with clay before painting. The figures of birds and animals with their young often have very human expressions further adding to the spontaneity of the art created. Given the effect of time and the elements the art is constantly renewed, repainted, reformed and added on too. This Rajwar community tradition came to notice in the early 1980’s when Bharat Bhavan the arts complex opened in Bhopal under the leadership of Ashok Vajpeyi The Roopankar Museum that formed a part of the Bhavan was founded and led by the distinguished thinker, painter, poet and writer J. Swaminathan (1928 – 1994) who’s thinking on art challenged the established canon that divided the contemporary and modern from the folk and tribal. His contribution to this debate continues to inspire till today. It was Swaminathan along with students of art and others under his guidance who fanned across the the region travelling to its most remote parts to collect and documenting the folk and tribal arts. This collection formed the core of the Roopankar museum. The Bhitti Chitra tradition of the Sarguja district work thus came to the notice of the researchers from Bharat Bhavan and immediate interest was generated. It was Soonabai, a legend in her lifetime whose work had caught their eye as in her home she had created a universe of figures that she called her ‘companions.’ Some of her work was taken to Roopanker and further orders were placed. Soonabai’s travelled to Bhopal and then further afield, across India and overseas, demonstrating her art and creating artworks. Many distinctions followed and the recognition of the arts of the Rajwara community received worldwide acclaim. Today, much after the demise of Soonabai in 2007 one of the traditions foremost bearers is Sundaribai of Sirpotanga Village in Sarguja District who while from the Rajwara community belongs to a family that was traditionally engaged in restoration mud work for the local kachche makan/ mud houses in the area. As a young child she played with clay, this led her on to make pots, cups, jars and soon her clay moulded figurines developed into birds, parrots, monkeys, flowers and figures. Married at the age of 11 she continued her work. Her designs expanded to cover walls and doorways as well as standalone pieces. Practising commercially for almost 40 years now her family has followed in her footsteps - from her husband, her sister-in-law, her only son to her six grandchildren who are continuing their education while learning the finer points of the craft. Bhitti chitra today remains a vibrant tradition with the women continuing to sculpt and paint their homes during festivities. While the focus of attention is the deity – Lord Shiva and Lord Krishna among others placed within the profusion of flowers and leaves phool pati and trellis fretwork jaals that fill the background. Birds and animals – monkeys, buffalos, horses, dogs, cats and as well as human figures add to the scene. With the commercialisation of Bhitti Chitra the numbers involved have grown as can be seen in Sundaribai’s case where her whole family, including the men now are involved in the work. Showcased in museums, and exhibitions often in heights of several feet it is now has a widened clientele both nationally and internationally. With the artists now seasoned traveller whose themes have expanded to include a landscape that extends from the everyday village life to include other backdrops. SONA BAI'S WORK [gallery ids="165389,165390,165391,165392,165393"] SUNDARI BAI'S WORK [gallery ids="165394,165395,165396,165397,165398,165399"] First published in the Sunday Herald.

Kani shawls and Jamewars (yardage for robes), known for their fine pashmina wool, wonderful range of colors and intricate patterns in tapestry technique and twill weave, were once produced in Kashmir during the Mughal period. Considered unique, precious and royal, they received a special place amidst other rare textiles. The tradition of the Kani shawl journeyed to India from central Asia along with the Mughals and was influenced by local cultural mores, pushing the technique to its creative limit. By the end of the 19th century though this thriving shawl industry had gradually declined. Attempts at revival have been made but the socio-cultural conditions that had made such production possible have changed. Normal production of such exquisite pieces of such high quality is not possible anymore. The continuing tradition of darning itself becomes extremely significant in this context. The Rafoogars (darners) with their special darning skills have been responsible in keeping these exquisite pieces alive, in circulation and ensured their continued use through an interesting transformation of the product and the market.

At a Symposium on Indian Textile Traditions at the Textile Museum, Washington DC recently, I came across this sign at the entrance to the exhibition:

At a Symposium on Indian Textile Traditions at the Textile Museum, Washington DC recently, I came across this sign at the entrance to the exhibition:

A Garden of Shawls: The Buta and its seeds

Welcome to the Textile Museum

We ask you not to touch the textiles on display. It is a privilege to view them outside the confines of cases and Plexiglas, a privilege we ask you to respect. Textile fibers are highly sensitive to damaging deposits of oil and dirt found on our hands. In addition, over exposure to light, heat and humidity is detrimental. As a result our galleries are cool and light levels are low. Please understand the needs of the textiles. Enjoy your visit and help us to preserve these important works of art for generations to come. Thank you.

In a flash, it brought back childhood memories of summer vacations in my grandfather’s ancestral house in Najibabad in Western Uttar Pradesh where it was a pleasure and great privilege to view, handle, touch, feel and smell these antique Kanishawls and robes brought by the Rafoogars, well known to repair and restore especially these shawls. They are also known as Shawlwale or the shawl people being in the shawl trade for many generations. Najibabad is home of several darners and hub for Kani shawl repair. Repair of these precious shawls is carried out throughout the year. The darners sit on the floors in their verandahs or in the open courtyard for sufficient daylight even in hot summer months, spread the shawls on the ground for inspection and then mend them according to the need. These pieces pass through several hands/over their knees in this intricate process of darning and restoration, before it is returned to its owner or sold to a new patron.Having spent long years of childhood there, old Kani shawls and robes were very much part of our life and held center stage amidst other crafts/ textiles from various regions of the country. The yearly ritual of airing our warm woolens after monsoon had always been a thrilling experience for us as children. Every winter we saw these exquisite shawls being pulled out of the storage with other warm clothes. They had a special storage place. Any faulty or careless storage was out of question lest mites and bugs caused damage to these priceless items, otherwise one had to inspect any destruction they had caused. However the sheer impact of age too often makes textiles fragile. Being worn and used they would inevitably require mending. No one missed a heart beat though because the shawl repairmen was a call away. When the Rafoogars visited our homes to repair the shawls they also brought along old shawls carefully wrapped in fine cottons, acquired cheap as rejects unfit for further use from earlier owners. With their skill and ability to mend and restore these priceless, tattered, discarded rags, the Rafoogars would restore, transform and renew these pieces for further sale to new patrons and collectors with expensive tastes. It was so natural then, as it is even now, to experience and admire the beauty and refined workmanship of these unique textiles Even if one could not afford to buy a shawl it was always a treat going through the bundle, mesmerized by their beauty, the intricacy and complexity of weaves and design, and of course the fine skills of the Rafoogars in repairing them. For us as children, these shawls were wonderful treasures and the men were like magicians showing one fine piece after another. Some of them never seemed to mind or feel offended if the pieces were not always bought but liked the involvement and respected ones love, interest, and appreciation for these pieces and were happy to share with us.

This interaction of generations continues to date.

One always appreciated the skills of the Rafoogars whose repair of the shawls was almost invisible to the naked eye. But along with the invisible repair, they too have remained invisible to the world at large. Possibly, ’sheer invisibility’ being the hallmark of good darning!

One wonders how shawls made in Kashmir reached these darners in Najibabad. Are they related to the Kashmiri darners or descendents of the seamsters or embroiderers of Kashmir who played a significant role during the original production of these shawls or their role shifted once such production stopped? Or did they master the special needlework skills of darning much later when the shawls needed maintenance, repair and renewal.

We have yet to find answers to establish these links with Kashmir but the fact is that few families settled in Najibabad about 250 years ago during the reign of Najibuddaulah, a Rohilla chief from Afghanistan in mid 18th century.Foster (1793) gives us interesting details as regards the situation of Najibabad and the climate of the surrounding country. “Najibuddaulah, who built this town, saw that its situation would facilitate the commerce of Kashmir, which having been diverted from its former channel of Lahore and Delhi, by the inroads of Sicques, Maharattas and Afghans, took course through the mountains at the head of the Punjab, and was introduced into the Rohilla (country) through the Lall Dong Pass. This inducement, with the desire of establishing a mart for the Hindoos of the adjacent mountains, probably influenced the choice of this spot, which otherwise is not favourable for the site of a capital town, being low and surrounded by swampy grounds…. since the death of its founder, Najibabad had fallen from its former importance and seems now to be chiefly upheld by the languishing trade of Kashmir.”

Thus, being on the trade route from Kashmir to Bengal, some Rafoogars, also in the shawl trade, migrated from Kashmir via Punjab and settled in Najibabad. One of the darners possesses a family record of nine generations, helping trace their ancestry to Timris Kala, Tabab-e-Bukhara who arrived in Najibabad via Ropar. Other families shifted here from the neighboring villages of Bijnor. An old haveli called Rafoogaran(home for rafoogars) still exists in Najibabad.

An entirely male occupation, most of the darners are Sunni Muslims, who settled in Rampura and Mohalla Dharamdas. Gradually, they spread to other areas of the town and migrated to other neighboring villages like Jalalabad, Kaleri, Alipura, Mandawar, Akbarabad and bigger towns/cities like Dehradun, Mussourie, Saharanpur, Meerut, Jodhpur, Lucknow, Benaras and Delhi in search of darning work.

These darners were earlier engaged in stitching cotton selvedges (kanni) on rafal and Pashmina woolen shawls manufactured in Amritsar. This led them to travel from one place to another to sell these new shawls or to repair old Pashminas, (especially Kanishawls) to eventually be involved in the Kani shawl trade. Some migrated to Pakistan during the partition in 1947 where they still work as darners in Karachi and Lahore.

Today they are also employed by museums, shawl traders or work in dry-cleaning shops. The onset of winter means renewed business for the darners when they travel to towns and cities, meeting old clients and making new ones. Some visit the hill resorts in the summer but the rest of the year they are back home busily mending and assembling fragments of tattered shawls or even procure shawls from princely states or families who cannot afford to maintain them any longer.

Many of the younger members in their families now opt for other professions, and therefore men from other communities have learnt the darning skill to meet the present needs in textile restoration.

The darners have been the conduits of time. Their special skills have been part of our living tradition. The practice of our Indian ways of ‘use, mend and re-use’ has kept their darning skills alive and are a key factor in rescuing a number of priceless pieces textiles from further destructions or till they are well preserved in the controlled environment of any museum

While the shawls of Kashmir have been elaborately and well researched, their unique weaving and fine needlework celebrated, an important role and major contribution of Rafoogars in the maintenance of these priceless shawls by highly intricate and laborious work of restoration and renewal of these pieces, practiced for generations has yet to be recognized.

Though there is an urgent need to understand the complexity of their skill and practice. The continuous demand in the market has been responsible for the cutting and destroying of many of these magnificent original Long shawls and Rumals to create smaller shawls, stoles and scarves catering to the present clientele who prefer it for the size and price.

With every generation, tradition evolves in order to survive. It is a challenge to preserve and continue with our inherited skills and knowledge of the past. The circulation and recycling of these shawls makes one realize their contribution in the survival of what remains of the Kani shawls today. There is a value addition to these restored priceless textiles, giving a new life to these textiles of the Past.

Perhaps we need to recognize darning as an independent practice and the contribution of these darners in preservation and continuation of their inherited skills, creativity and knowledge in the survival of what remain of the Kani shawls today.

Some of them never seemed to mind or feel offended if the pieces were not always bought but liked the involvement and respected ones love, interest, and appreciation for these pieces and were happy to share with us.

This interaction of generations continues to date.

One always appreciated the skills of the Rafoogars whose repair of the shawls was almost invisible to the naked eye. But along with the invisible repair, they too have remained invisible to the world at large. Possibly, ’sheer invisibility’ being the hallmark of good darning!

One wonders how shawls made in Kashmir reached these darners in Najibabad. Are they related to the Kashmiri darners or descendents of the seamsters or embroiderers of Kashmir who played a significant role during the original production of these shawls or their role shifted once such production stopped? Or did they master the special needlework skills of darning much later when the shawls needed maintenance, repair and renewal.

We have yet to find answers to establish these links with Kashmir but the fact is that few families settled in Najibabad about 250 years ago during the reign of Najibuddaulah, a Rohilla chief from Afghanistan in mid 18th century.Foster (1793) gives us interesting details as regards the situation of Najibabad and the climate of the surrounding country. “Najibuddaulah, who built this town, saw that its situation would facilitate the commerce of Kashmir, which having been diverted from its former channel of Lahore and Delhi, by the inroads of Sicques, Maharattas and Afghans, took course through the mountains at the head of the Punjab, and was introduced into the Rohilla (country) through the Lall Dong Pass. This inducement, with the desire of establishing a mart for the Hindoos of the adjacent mountains, probably influenced the choice of this spot, which otherwise is not favourable for the site of a capital town, being low and surrounded by swampy grounds…. since the death of its founder, Najibabad had fallen from its former importance and seems now to be chiefly upheld by the languishing trade of Kashmir.”

Thus, being on the trade route from Kashmir to Bengal, some Rafoogars, also in the shawl trade, migrated from Kashmir via Punjab and settled in Najibabad. One of the darners possesses a family record of nine generations, helping trace their ancestry to Timris Kala, Tabab-e-Bukhara who arrived in Najibabad via Ropar. Other families shifted here from the neighboring villages of Bijnor. An old haveli called Rafoogaran(home for rafoogars) still exists in Najibabad.

An entirely male occupation, most of the darners are Sunni Muslims, who settled in Rampura and Mohalla Dharamdas. Gradually, they spread to other areas of the town and migrated to other neighboring villages like Jalalabad, Kaleri, Alipura, Mandawar, Akbarabad and bigger towns/cities like Dehradun, Mussourie, Saharanpur, Meerut, Jodhpur, Lucknow, Benaras and Delhi in search of darning work.

These darners were earlier engaged in stitching cotton selvedges (kanni) on rafal and Pashmina woolen shawls manufactured in Amritsar. This led them to travel from one place to another to sell these new shawls or to repair old Pashminas, (especially Kanishawls) to eventually be involved in the Kani shawl trade. Some migrated to Pakistan during the partition in 1947 where they still work as darners in Karachi and Lahore.

Today they are also employed by museums, shawl traders or work in dry-cleaning shops. The onset of winter means renewed business for the darners when they travel to towns and cities, meeting old clients and making new ones. Some visit the hill resorts in the summer but the rest of the year they are back home busily mending and assembling fragments of tattered shawls or even procure shawls from princely states or families who cannot afford to maintain them any longer.

Many of the younger members in their families now opt for other professions, and therefore men from other communities have learnt the darning skill to meet the present needs in textile restoration.

The darners have been the conduits of time. Their special skills have been part of our living tradition. The practice of our Indian ways of ‘use, mend and re-use’ has kept their darning skills alive and are a key factor in rescuing a number of priceless pieces textiles from further destructions or till they are well preserved in the controlled environment of any museum

While the shawls of Kashmir have been elaborately and well researched, their unique weaving and fine needlework celebrated, an important role and major contribution of Rafoogars in the maintenance of these priceless shawls by highly intricate and laborious work of restoration and renewal of these pieces, practiced for generations has yet to be recognized.

Though there is an urgent need to understand the complexity of their skill and practice. The continuous demand in the market has been responsible for the cutting and destroying of many of these magnificent original Long shawls and Rumals to create smaller shawls, stoles and scarves catering to the present clientele who prefer it for the size and price.

With every generation, tradition evolves in order to survive. It is a challenge to preserve and continue with our inherited skills and knowledge of the past. The circulation and recycling of these shawls makes one realize their contribution in the survival of what remains of the Kani shawls today. There is a value addition to these restored priceless textiles, giving a new life to these textiles of the Past.

Perhaps we need to recognize darning as an independent practice and the contribution of these darners in preservation and continuation of their inherited skills, creativity and knowledge in the survival of what remain of the Kani shawls today.

Introduction: Who I am & What I’m Doing

I came to India to learn about how the country, culture and currency of my birth are changing the rest of the world. I came to India to discover how a country three thousand years in the making could be loosing its traditional heritage to modern market forces and factory-made goods. I came to India to immerse myself in the ever evolving world of Indian arts and crafts and examine their makers’ statuses. When I applied for my Fulbright grant, now almost two years ago, I had in mind a project full of hope, of homegrown resistance to westernization; full of promise for a better life for the rural artisan with the increase of technology through rural development programs. Instead I found a few brave organizations that are working relentlessly against the odds to provide both increased income and/or cultural preservation. Among the most well known of these organizations is Seva Mandir and its craft/income generation program, Sadhna. So after spending half a year doing research on various Indian folk crafts and craft development programs in the bustling city of New Delhi, I set out for the much smaller and less hectic city of Udaipur, located in Southern Rajasthan. I was to spend the next two weeks working as a volunteer for Sadhna and discovering what goes on behind the scenes at a typical development NGO.Background Check: What Seva Mandir and Sadhna Really Do

Dr. Mohan Singh Mehta began Seva Mandir in 1966 in an attempt to raise awareness about the “particular backwardness and political stagnation of Rajasthan.” The organization started with a campaign for literacy but soon found that a steady income and proper nutrition and health were needed before villagers could concentrate on learning how to read. In the 1970s Seva Mandir’s popularity often encouraged its village level employees to run for government offices. Unfortunately, once there, the new office holders found they had little power to change the corruption. This prompted Seva Mandir to form village groups in the 1980s. Later that decade, Village Committees were established to help distribute aid from alternative organizations for poverty alleviation. Seva Mandir began to realize that the government alone could not solve the problems facing rural Udaipur. Currently, Seva Mandir is working in 583 villages in six block districts educating villagers about natural resource management, education, health, women and child development and institution building. |

The women did not see the lack of physical strain and the option of working from home as benefits that outweighed the income cut. However, the most common reason for drop-out was the shifting of villages at the time of marriage. Many of the women who worked for Sadhna had to leave their paternal village at marriage, sometimes into a village that was either too far removed from Sadhna or did not have a Seva Mandir block office in the district. |

Another problem arose when Sadhna began encouraging the women to attend exhibitions on their own. Formerly, a Sadhna staff member would accompany the women to exhibitions and manage the sales and stock records. Despite Sadhna’s care to match all illiterate women with literate ones, they still had a difficult time in managing the records and sorting the stock after the exhibition was over. The Sadhna staff, however, feels that with more training and exposure the women will be successful in the future.

A Personal Look: Interview with JayaI had the opportunity to catch up with the newest addition to the Sadhna team during one of the above mentioned power outages. Jaya, a recent graduate from NIFT in New Delhi, joined Sadhna as their design coordinator in January of this year. However, she spent her last semester of college working on her final project for graduation at Seva Mandir. So needless to say Jaya was well acquainted with the technicalities of working for a non-profit NGO. She explained that although she was trained as a designer, most of the design work done at Sadhna was generally spontaneous because there are no regular quotas for new designs as there are in other craft design firms. However, Sadhna does occasionally work with other designers and marketing agencies in order to make their products more viable in domestic city and international markets. Sadhna has affiliations with such NGOs as Aid to Artisan in the USA and Craftsbridge in Pune. What struck me most about Jaya during our short interview was her obvious passion for the work that she does. Not only the design and craft side of Sadhna, but more importantly the income generation and poverty alleviation aspect. |

|

| Jaya is in charge of production and distribution of work. She must calculate how many pieces are to be made each year and then break that down into the number of pieces to be made each month, each week and each day. She delegates the responsibility of creating these garments, bags and home-decor items to women from 10 different areas. However daunting this task might seem, what impressed me most about Jaya’s dedication to her work was summed up when she said, “We have three hundred women who need work. Giving them work is more important than profit.” Organizing and running workshops is another of Jaya’s many tasks at Sadhna. I had the occasion of witnessing the end of one of these workshops on the first day of my internship. The workshops were organized so that the women would generate images to be used on future fabric pieces. |  |