JOURNAL ARCHIVE

The landmark Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 showcased the best resources and products from over 33 British dominions. Inaugurated by Queen Victoria it received over 5.5 million visitors – an unprecedented record for an exhibition. The comprehensive catalogue that accompanied the exhibition while describing the magnificent array displayed at the Indian pavilion contained these cryptic words “3 pieces of the Benaras Kinkhabs or cloth of gold brocades call for no special remarks….” Going on to say “…but (they) command attention as the most effective of all the fabrics shown.” Elaborating further they described the fabrics as “the gorgeous and beautiful Kinkhabs and gold brocades from the looms of the holy Banaras” Kashi, Banaras, Varanasi - the many names of one of the oldest inhabited cities of the world whose textile links have been and remain an interinsic part of the city. From the c. 2nd century B.C when Patanjal, the great grammarian in his text Mahabhasya mentions kasika textiles as being more precious than others to references in ancient Buddhist and Jain literary sources that mention Kashi as an important weaving and trading centre, the glimpses continue through the ages. The principle history of Mahmud of Gazni, Tarikh –us –Subuktigin by Baihaqiin written in the 10th century listed the textiles of Banaras as one of the prized plunders of his raids. Kabir the great weaver-mystic poet lived and worked in Banaras in the 15th century. In his 16th century chronicle Ralph Fitch, merchant and trader wrote of the cloth is made there for the Mughal court. Though his visit to Banaras was brief Jean Baptiste Tavernier the French jeweler and merchant was struck by the wealth of Banaras that he credited to its textile industry. Accounts of weaving and the trade in the textiles of Banaras continued from the Storia Do Mogor by Nicolai Manucci, the Italian who wrote of the great trade of gold and silver fabrics from Banaras to other parts of India and overseas in his detailed account of the Mughal court in the late 17th century to writings on Banaras up to the present times the unchallengable links remain. The textiles that writers and traders exclaimed about were not only the sumptuous silk brocades or the Tarbana with its silk warp and metallic gold weft that created the fine, tissue textiles and the fine cotton weaves that Banaras was known for since antiquity but the legendary Kinkhab the jewel like cloth of gold and silver literally meaning 'little dreams' in Urdu. With over a hundred thousand people engaged in both the weaving and the pre and postloom activity the economy of Banaras remains inextricable connected to the loom. Using techniques that include the Kadwa which uses several weft shuttles of differently coloured threads to create the patterns to the Urtu where different grounds are made possible in individual patterns. The Fekwa throw shuttle method results in surface patterning to the Katraua cutwork patterning. The Nal Pherwa three shuttle technique where two of the shuttles wove the contrast borders while the third is used for the base the textiles are woven using a variety of loom structures from the pit looms with throw shuttles to the Gathwa thread frame and Jacquard looms. The continuing familial handloom traditions with weaves whose structures, techniques and physical quality remains related to the past can be seen in the 6th generation of the family that wove the cloth of gold that were displayed at the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition. Located in Pilli Kothi, the ancient stronghold of Banarasi weaving the family patriarch Badrudin Ansari of Kasim Silk Emporium strives to achieve a balance between the preservation of the established while innovating and adapting textures and patterns to the times and changing clientele. While Kinkhwab with specially commissioned real gold and silver metalic yarns continue to be woven – taking two months to complete a bolt of four meters - the family is now equally known for the weaving of the Gyasar brocades for Buddhist monasteries across the globe. The densely patterned silk with auspicious Buddhist symbols and floral imagery is rich with gold and silver threads. Usually woven in widths of 24 inches in pit-looms using the discontinuous supplementary warp technique it is used as altar pieces, drapery for walls, canopies, door and window frames, robes for the Buddhist clergy, as hangings, as a backing for Thankha paintings. The latest addition being the use of the textiles in building authentic film sets for Hollywood movies like Kundan and Back to Tibet. For the laity the weaves are woven for special wear as robes for women , capes for men and as trims.The weaving of the Gyasar was introduced at the time of Badrudin Ansari’s father Haji Nooruddin. Since the 1970’s the weaves have been supplied for traditional dress to the Royal family of Bhutan, while their Kinkhab are used across the globe for both dress and furnishing in palaces and luxury homes. The house of Kasim is also known for its Morpankhi, woven with peacock feathers combined with a silk warp. The textile shimmers in iridescent colors and Badrudin Ansari was awarded the Presidents National Award in 1987for his skill in weaving it. The feathers gathered in the monsoon when the peacock moults are painstaking woven in a time consuming process that allows for the completion of a 8 meter bolt taking about 2 months to complete with the furnishing fabric supplied to not only Rastrapati Bhavan but to the Kuwait Royal home. Continuing to nurture their ties and trade links with the world outside they now have a customer base spread across the globe that includes international designers to their the weaving of sacerdotal fabrics for Greek Orthodox churches. [gallery ids="165458,165459,165460,165461,165462,165463,165464"] First published in the Sunday Herald.

Issue #002, Monsoon, 2019 ISSN: 2581- 9410 Design intervention has been an established initiative of development projects initiated by Governments and NGOs across the world as a means to enhance market reach and the livelihood of craft communities. However, these multiple initiatives which are meant to support craftspeople and their communities often end up benefiting the designer’s and other commercial interests. Innumerable instances have been cited by craftspeople and others on the ethics of engagement where design development of craft traditions has ended up publicizing the designer while the craftsperson has continued to remain unnamed and unknown. In the design world, practitioners and students are well aware of the moral issues and laws governing copying and design infringements. Design practitioners use all means to protect their designs and ideas as they are alert to their moral rights, economic benefits and future business potential. However, the same level of rigor does not seem to always apply when the designers deal with traditional craft communities. While marketing pundits eulogize brand identities and designer products are the current rage, charges of cheating and infringement of design are not infrequent in these circles and counter-charges grab headlines. However, amidst all this babble of newsprint and televised footage, there is a marked absence of any mention of copying associated with the many hundreds of indigenous crafts and textiles that exist in this country. Is this deafening silence because there is no copying of these hallowed traditions? Or is it because there is a widely accepted view that copying from traditional craftsperson’s and weavers is acceptable, and, in fact, even given tacit approval? We have all seen a Warli painting featured across the pallu of one famous designer’s sari, a Madhubani motif on a jacket of another; iconic block-prints that have been screen-printed, a handloom replicated on the power-loom. Craftspeople, artists and weavers who have sewn and embroidered, cast and molded, engraved and etched, printed and painted India’s millennia old cultural identity seem to have no place in popular conversations on ‘design’ and ‘brand’ and apparently, no perceived rights or ownership of their familial and community knowledge. Mainly located in rural1 areas, the craft sector in India provides employment to many millions of people. An overwhelming majority of whom belong to the weaker, more vulnerable sections of society, being either Scheduled caste or tribe or belonging to minorities or to ‘other backward classes’. It is an accepted truth that craftspeople and their communities are the holders and bearers of tradition, of skills and techniques, craft ritual and folklore. These hereditary skills are acquired through an inter-generational oral transmission, sharpened by apprenticeship and long practice. This amalgam of knowledge on material and processes, artistic expression and ritual meaning has responded and evolved with changing ecologies and environs over the ages, continuing to be an intrinsic part of craft practice today. Designers and manufacturers are alert to the values inherent in craft products, differing as they do from other goods. Endowed with symbolic meanings that are often greater than their inherent usefulness, these products play a special role in peoples’ lives. The Moosaris of Kerala who cast the bell metal Charakku cooking utensils in diameters of up to 8 feet, the Sthapatis of Swamimalia who cast the bronze idols are only some such examples. These craft genres are clearly delineated brand identities that have been honed over decades –often centuries – of aesthetic development, technological fine tuning, and innovation. Yet there is a strong perception within traditional craft communities of an inequality in their status as craft practitioners. While ‘new’ design input into the craft is assumed to be exclusively in the domain of the designer, crafts people, whose tradition is being explored, are relegated to a biddable, subservient role. This taxing paradox of value constantly confronts craftspeople wherein a high valuation is placed on the product, while they, the makers and holders of traditional craft knowledge are relegated to obscurity and anonymity. The additional challenge faced by crafts people is the ubiquitous availability of replicated and fake craft products that are marketed in high street stores in India and across the globe under the name of the craft or weaving cluster. Factory printed Bandhini, the traditional tied and dyed textile of Rajasthan and Gujarat to the rubber reproductions of the Kolahpuri chappals of Maharashtra, the textiles and T-shirts printed with Madhubani and Warli motifs, the iconic block prints of Bagh, Bagru, Sanganer, and other centers available in cheap screen printed copies to the famed hand woven brocades of Banaras now replicated on the power loom, are only a few such examples. The all-pervading availability of these fakes and ‘borrowings’ has hit craftspeople hard, not just economically by depriving them of the benefits of their traditional community knowledge but also deepening the perception of inequality and unfairness. Crafts people are ill-equipped to tackle this onslaught and this furthers their feeling of vulnerability. How to protect the moral right and intellectual property of craft communities over their millennium old creation and the potential economic benefit arising from it has been the subject of international debate since at least the 1982 when an expert group was convened and a sui generis model for intellectual property type protection of traditional cultural expressions was developed. (WIPO- UNESCO model provision law for folklore). After nearly three decades, however, debate still continues without any conclusive legal protective measure enacted so far. In view of the slow progress of debate at international level, some of the countries have taken initiatives at the national level to respond to their particular context and needs. Panama is one of a few countries in the world to have enacted a sui generis law to protect traditional cultural expressions and related knowledge2. Introduced in 2000, the law aims at protecting traditional dress, music, dance and major handicrafts. Just as in India, wide spread sale of cheap imitation of traditional handicrafts has been threatening the indigenous craftswomen of Panama, for whom the craft is often the sole means of income. A Label of Authenticity was introduced by the Government under the Law 20 to be attached to a numbers of indigenous crafts so as to guarantee their authenticity. Although the label of authenticity does not prevent the sales of cheap imitation, it allows people to differentiate authentic traditional products and encourages buyers to pay a fair price to the producers3. In New Zealand, where the Government has a clear policy to recognize Maori rights, the national Trade Marks Act 2002 is aimed, amongst others, “to address Maori concerns relating to the registration of trade marks that contain a Maori sign, including imagery and text”4. The Act foresees the appointment of Advisory Committee whose function is to “advise the Commissioner whether the proposed use or registration of a trade mark that is, or appears to be, derivative of a Maori sign, including text and imagery, is, or is likely to be, offensive to Maori”5. Besides, Maori is one example of a society that manages property law through customary rights (Ragavan S, 1999). In India, the enactment of Geographical Indication is expected to bring much needed legal protection of community knowledge. A family of Trade-Related Intellectual Properties Right, GI Act aims at identifying good as originating from a particular place, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristics of the good become essentially attributable to its geographical origin. GI is commonly given to natural, agricultural and manufactures goods. The GI tag enables producers to differentiate their products from competing products and is considered to be effective tool to protect those good associated with or deriving from local cultural traditions. Till July 2011, 153 goods have been registered under the Act out of which 99 belong to handicraft / folk art tradition including Chanderi weaving of Madhya Pradesh, Madhubani painting of Bihar and Pochampalli Ikat of Andhra Pradesh6. However it is still a new system. The number of registered GI is not yet sufficient to cover the wide range of traditional crafts of India7. Besides, the system is mean to certify the ‘place’ of origin of a product and not necessarily to recognize the specific group of ‘people’ who make it. Further, it is yet to be demonstrated how the registration system concretely benefit the craftspeople and protects their economic and cultural rights. A strong post-registration follow-up mechanism is necessary to effectively link GI recognition and the well-being of craft communities. We therefore continue to live and struggle in an imperfect world. In the meantime, examples of passing-off, misappropriation and borrowing of traditional designs continue to impede craftspeople and their communities. In the absence of appropriate institutional and legal protection for the time being, we need to explore alternatives to alleviate the situation. The Fair-trade movement, a global association with a growing membership and increasing awareness among consumers is a well-known example of ethical standard setting. Defining the relationship between producers and buyers, addressing issues ranging from fair wages, child labor to a healthy working environment its voluntary nature is an interesting example of changing dynamics. Then, why not establishing a similar ethical guideline between designers and artisans? This paper presents a case for change through the creation of a voluntary code of ethics governing design interaction. A self regulated mechanism that seeks to redress the basis of engagement between crafts people and designers, a moral binding, if we may, to create a fair and ethical sharing of benefits between designers and craftspeople. The guiding philosophy being encapsulated in the Co-creating Code of ethics for designers and others, based on an acknowledgment of the ownership of traditional cultural knowledge, creating parity and respecting the rights of craftspeople. The Co-creating Code, voluntarily signed up to by designers is in effect a moral bond that addresses the imbalances in the process of interaction and the benefits that accrue thereof. The Code serving as a practical guideline to the interactions and the issues that arise in the interface for a well-balanced and mutually beneficial relationship. The building blocks to the Co-creating Code are the recognition of the craftspeople as equal partner in the process of design development substantiated by parity in apportioning both credit and the economic benefits of design development. While the guiding values and standards need to be debated further, the Co-creating Code is a constructive move towards protection of the economic and moral interests of crafts people, who are vulnerable to powerful commercial interests. Creating the confidence that issues of misuse, borrowing and misappropriation of their traditional cultural knowledge is being addressed. The principals of the Co-creating Code work to ensure a level playing field between professional designers and traditional craftspeople, giving due acknowledgement to the craftsperson’s knowledge and skill, an equitable attribution, by naming and placing the craftsperson in the center of design development, recognizing their rights as holders of traditional knowledge. Craftspeople thereby receive fair credit and recognition on the one hand and just economic remuneration on the other. In the long run the principles of co-creating will prove to be a valuable business asset creating trust, mutual respect and economic gain in a balanced manner for both designer and crafts people. Re-defining the roles both in the sharing of economic benefit and in credit sharing. Developing in effect a broad strategic view wherein the rights of the craftspeople are balanced in an equitable way with the contribution of designers. This then is, we hope, the first step to a repositioning of the setting between craftspeople and designers, a recasting of their role where their knowledge systems can no longer be harnessed without acknowledging ownership or apportioning benefits to them. References Publications All Indian Artisans Craftworkers Welfare Association (AIACA), 2010, Policy Briefs, Geographical Indications of India, Socio-Economic and Development Issues Craft Revival Trust/Artesania de Colombia, 2005, Designer Meets Artisan, Delhi, India Government of New Zealand, Trade Marks Act 2002 Ragavan S., 1999, Protection of Traditional Knowledge, Center for Intellectual Property Rights Advocacy, National Law School of India University, Bangalore, India. Ranjan, Aditi and MP Ranjan (ED.), 2007, Handmade in India WIPO, (year unknown), Panama: Empowering Indigenous Women Through a Better Protection and Marketing of Handicrafts”

Websites Census of India: http/www.censusindia.gov.in Craft Revival Trust: http/www.craftrevival.org Geographical Indication Registry: http:/www.ipindia.nic.in/girindia/

Endnotes:- According to the 2001 census there are 6,38,365 villages spread across India

- Law No. 20 (June 26, 2000) on a special intellectual property regime for the collective rights of indigenous communities, for the protection of their cultural identities and traditional knowledge.

- This information on Panama is drawn from a document of WIPO– “Panama: Empowering Indigenous Women Through a Better Protection and Marketing of Handicrafts”.

- Trade Marks Act 2002, New Zealand.

- Ibid.

- Geographical Indication Registry: http:/www.ipindia.nic.in/girindia/

- Craft Revival Trust (http//www.craftrevival.org) documents more than 880 different craft forms while recently published “Handmade in India” identifies some 516 meta craft clusters across India.

The Coconut constitutes a plant that belongs to Palmae family and is widely grown in tropical regions as it needs proper living environment for its growth and production. Coconut is well-known as a multipurpose plant and has been utilized and developed in a manner that yields a high economic value. Even, for that part of the plant that could be considered as waste, such as its fiber which is utilized among other uses as active charcoal; while the shell is often processed to create remarkable art work.

Coconut shell or kotti in Konkani, has biological function as the protector of the main fruit. Located in the inner side of the coconut fiber with its thickness around 3-6 mm. Coconut shell can be categorized as hard wood, yet has higher lignin level and lower cellulose level, and water level about 6-9% (counted based on dry weight), and especially composed of lignin, cellulose, and hemi-cellulose.

With above composition, thus art works from coconut shell have excellent quality, imperishable, and relatively easy to be formed. These features have resulted in the development of the modern coconut shell handicraft industry.

Instead of being thrown away or used as firewood for cooking dry coconut shells are carved in different designs, varnished and colored. Coconut shell craftwork involves tremendous creativity and is used for the creation of utility and decorative items by artisans who use their creativity to create items from utility to artistic and decorative. The items produced include Table lamps, flowerpots, table clocks, different idols and decorative items.

Carving Coconut shell is very difficult and only highly skilled craftsmen can make products out of it due to its hardness.

Coconut shell or kotti in Konkani, has biological function as the protector of the main fruit. Located in the inner side of the coconut fiber with its thickness around 3-6 mm. Coconut shell can be categorized as hard wood, yet has higher lignin level and lower cellulose level, and water level about 6-9% (counted based on dry weight), and especially composed of lignin, cellulose, and hemi-cellulose.

With above composition, thus art works from coconut shell have excellent quality, imperishable, and relatively easy to be formed. These features have resulted in the development of the modern coconut shell handicraft industry.

Instead of being thrown away or used as firewood for cooking dry coconut shells are carved in different designs, varnished and colored. Coconut shell craftwork involves tremendous creativity and is used for the creation of utility and decorative items by artisans who use their creativity to create items from utility to artistic and decorative. The items produced include Table lamps, flowerpots, table clocks, different idols and decorative items.

Carving Coconut shell is very difficult and only highly skilled craftsmen can make products out of it due to its hardness.

Traditionally, crafting objects out of coconut shell is to make household objects which was practiced by coconut farmers. They would scoop out the copra by making a neat hole at the top of the shell, and use the shell, which was the waste or by-product.

It is believed that as a craft, coconut shell carving could have been experimented with by craftsmen from the Vishwakarma community in Kerala. Traditionally involved in sword making and carving wood and ivory, they may have tried out coconut wood and shell as well.

Coconut shell craft has gained popularity only in the last few decades, and hence does not have a long history to boast off. However, a report mentions this craft being brought in from Iraq almost 900 years ago. It could be that the wood carving artisans from the Middle East and Persia were the first ones to try carving on coconut shell.

While Coconut shell craft is practiced all over the world, the craft has evolved and is being highly used as means of creative employment in different places around the world such as Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, Java, Maldives and Sri Lanka.

In India, coconut crafts have gained immense popularity and have become rather fashionable for their novelty and uniqueness. Tamil Nadu and other coastal states have abundance of skilled artisans for making coconut crafts.

Traditionally, crafting objects out of coconut shell is to make household objects which was practiced by coconut farmers. They would scoop out the copra by making a neat hole at the top of the shell, and use the shell, which was the waste or by-product.

It is believed that as a craft, coconut shell carving could have been experimented with by craftsmen from the Vishwakarma community in Kerala. Traditionally involved in sword making and carving wood and ivory, they may have tried out coconut wood and shell as well.

Coconut shell craft has gained popularity only in the last few decades, and hence does not have a long history to boast off. However, a report mentions this craft being brought in from Iraq almost 900 years ago. It could be that the wood carving artisans from the Middle East and Persia were the first ones to try carving on coconut shell.

While Coconut shell craft is practiced all over the world, the craft has evolved and is being highly used as means of creative employment in different places around the world such as Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, Java, Maldives and Sri Lanka.

In India, coconut crafts have gained immense popularity and have become rather fashionable for their novelty and uniqueness. Tamil Nadu and other coastal states have abundance of skilled artisans for making coconut crafts.

Coconut shell craft is primarily prevalent in Kerala in and around Calicut, Trivandrum, Attingal, Neyyatinkara and Quilandy in Kozhikode district in north Kerala.Other states where this craft is practiced are Goa, Andaman and Nicobar islands, West Bengal, Pondicherry, Tamil Nadu and the tribal belt of Bastar. Here, intricately designed patterns in white metal are inlayed in the shell and cut to make bangles.

Goa produces beautiful, decorative and utility items made out of coconut fiber. Apart from consuming the flesh of the coconut in the meals it has done wonders to earn livelihood for the local artists. Artists prepare decorative to utility items from the shells and its fiber. Brooms prepared from this material have a good life span and do not produce any dust out of it. Locals have been using spoons or davlo as locally called and other vessels made out of shells. These are safe to use.

The success of Coconut craft is because it is eco-friendly, and available almost free of cost. It is easy to work with once it has been mastered; it is durable, beautiful and utilitarian; it is available in abundance. The craft makes use of non-exhaustible natural resources and makes available an option to the harmful effects of plastics

The Process

Raw Material

Coconut shell is bought from coconut growers and from farmers who scoop out the coconut for sale in the market, also selling the dried shell. The coconut is scooped out by making a small neat hole. Shells are available in different shapes and sizes. Prices also vary.

The coconut shells are obtained from various coconut farms located in Tiptur, Tumkur and Hasan. Raw material is normally available easily. However, coconut shell of a particular shape and size if required for an order takes a long time to collect.

Coconut shell craft is primarily prevalent in Kerala in and around Calicut, Trivandrum, Attingal, Neyyatinkara and Quilandy in Kozhikode district in north Kerala.Other states where this craft is practiced are Goa, Andaman and Nicobar islands, West Bengal, Pondicherry, Tamil Nadu and the tribal belt of Bastar. Here, intricately designed patterns in white metal are inlayed in the shell and cut to make bangles.

Goa produces beautiful, decorative and utility items made out of coconut fiber. Apart from consuming the flesh of the coconut in the meals it has done wonders to earn livelihood for the local artists. Artists prepare decorative to utility items from the shells and its fiber. Brooms prepared from this material have a good life span and do not produce any dust out of it. Locals have been using spoons or davlo as locally called and other vessels made out of shells. These are safe to use.

The success of Coconut craft is because it is eco-friendly, and available almost free of cost. It is easy to work with once it has been mastered; it is durable, beautiful and utilitarian; it is available in abundance. The craft makes use of non-exhaustible natural resources and makes available an option to the harmful effects of plastics

The Process

Raw Material

Coconut shell is bought from coconut growers and from farmers who scoop out the coconut for sale in the market, also selling the dried shell. The coconut is scooped out by making a small neat hole. Shells are available in different shapes and sizes. Prices also vary.

The coconut shells are obtained from various coconut farms located in Tiptur, Tumkur and Hasan. Raw material is normally available easily. However, coconut shell of a particular shape and size if required for an order takes a long time to collect.

Selecting the Right Shell

While selecting the coconut shell, the following points need to be kept in mind:

Shape of the shell:

Select the shell of a required size, thickness and shade needed to complete the article. Irregularly shaped shells cannot be used to make symmetrical objects.

Un-cracked shells:

Check that the shell does not have cracks developed either due to direct sunlight or due to a wrong way of breaking. This can be tested by a sound-test. An iron nail, or any iron piece, is struck on the shell. A good, un-cracked shell will give a clear deep sound, whereas a cracked shell will give a distorted sound. One could also test a shell by dropping it on a cement floor, and judging by the sound-test. Very often, it is seen that the cracks are identified only when the shell is polished at the final stage. This means the entire effort goes in vain.

Oil-free shell:

Selected shells should not have oil-marks on them. Often, very dry coconut, or copra, releases oil inside the shell itself. This is easily absorbed by the shell. This oil mark remains for a long period and spoils the look of the craft. Besides, it is noticed that such shells do not join firmly and there is a chance of the joints being separated.

Tools needed:

Selecting the Right Shell

While selecting the coconut shell, the following points need to be kept in mind:

Shape of the shell:

Select the shell of a required size, thickness and shade needed to complete the article. Irregularly shaped shells cannot be used to make symmetrical objects.

Un-cracked shells:

Check that the shell does not have cracks developed either due to direct sunlight or due to a wrong way of breaking. This can be tested by a sound-test. An iron nail, or any iron piece, is struck on the shell. A good, un-cracked shell will give a clear deep sound, whereas a cracked shell will give a distorted sound. One could also test a shell by dropping it on a cement floor, and judging by the sound-test. Very often, it is seen that the cracks are identified only when the shell is polished at the final stage. This means the entire effort goes in vain.

Oil-free shell:

Selected shells should not have oil-marks on them. Often, very dry coconut, or copra, releases oil inside the shell itself. This is easily absorbed by the shell. This oil mark remains for a long period and spoils the look of the craft. Besides, it is noticed that such shells do not join firmly and there is a chance of the joints being separated.

Tools needed:

- Hand drill

- Files : Rough flat file

- Round file

- Half-round file

- Triangular file

- Smooth file

- Carving chisels : Carving chisels are used for intricate designs and sculpting; cutting edges are many; such as gouge, skew, parting, straight, paring, and

- V-groove.

- Mortice chisel

- Lock mortice chisel

- Carving gouge

- Saws –

- coping saw

- fret saw

- hack saw

- Metal mould

- Table vice

Process

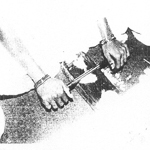

The process of coconut crafts involves sketching, cutting, sanding, and buffing to create the finished product. The craft production process for the shell craft is as follows:

Process

The process of coconut crafts involves sketching, cutting, sanding, and buffing to create the finished product. The craft production process for the shell craft is as follows:

- Choosing the right shell for the product that has to be developed.

- Scraping the inner surface of the shell with files to clean the husk on the shell, thus making it smooth.

- The shell is cut open with a hack-saw, the cut determined by the shape and size of the product to be made. The inner part is smoothened with a chisel.

- Smaller portions are cut from the hemispherical cut open shell with a hack-saw. The shape to be cut is drawn on the inside of the shell and the bow blade is inserted through a small hole. In case of a complicated design, for example if a piece of jewelry is to be made, a photocopied paper stencil is stuck on the inside surface of the shell and the design is curved out using a bow blade. If a circle is to be cut then a paper stencil is made. This is stuck on the inside surface of a cut portion of a shell, the bow blade is inserted and the circle curved out from the shell. Smaller elements are cut and stuck on to the main piece for ornamentation.

- After a shape is cut out, the edges are made smooth by filing or by sanding with sand paper.

- This process is followed repeatedly till the finish is satisfactory.

- After the article is made small hooks are attached if required. This is done by drilling a small hole and sticking the metal hook using a strong adhesive such as Fevikwik.

- In case of a bigger object such as an ice cream cup or a bowl, the whole shell is used by cutting it as per the required size. Various designs are engraved in the shell using a file.

- After the object is made it is sanded with sand paper till it is smooth. First boot polish is applied and then a final coating of French polish is given for high class finishing. Alternatively, if a glossy finish is desired, it is given a coat of synthetic varnish. If the surface is to have a dark finish then it is painted before the varnish coat is applied. The inside of the object in this case is first rubbed with sand paper to get the desired smoothness and then it is buffed on the machine. No varnish or bees wax is applied on the inside if the object is to hold foodstuff.

- The piece is dried in the sun.

Protecting the Shell

Durability of the shell craft

Protecting the Shell

Durability of the shell craft

- Due to the uniqueness of the shell, and its content, articles made from coconut shell have a very long life. These articles can remain for over a hundred years. Termites and other insects do not attack them. But one should protect them from rats.

- If the shell is dumped for a long period, it may catch fungus on the outer fibre or the inner side. But the hard portion of the shell remains unaffected.

- Shells should be protected from direct sunlight. Strong direct sunlight may lead the shell to develop cracks, which makes it useless to work with.

- Basic jewelry such as ear rings, ear drops, pendants and necklaces.

- Key rings, bowls, ice cream cups, spoons with a coconut wood handle.

- Car seat covers, pen holders, coasters, place mats and buttons.

Bibliography

Bibliography

- http:/xa.yimg.com/kq/groups/14872704/2065213887/name/coconutbook49withoutpics.pdf

- http:/www.indianetzone.com/1/coconut_craft.htm

- http/www.aiacaonline.org/pdf/coconut-craft-extended-documentation.pdf

- http/www.vibrantnature.co.in/coconutshelldetails.htm

- http/www.craftandartisans.com › Coconut

- http/www.squidoo.com › So Crafty

- http/goahandicrafts.com/coconut-shell-craft

- http/www.indianetzone.com › ... › Types of Indian Crafts › Wood Craft

- http:/www.goodlifer.com/2009/07/the-ethical-fashion-forum

Coconut trees grow all over Kerala, and the coconut is a fruit which is used in its entirety. Smaller coconut shell articles are also made in Trivandrum, Attingal and Neyyatinkara, while larger items are made in Quilandy in Kozhikode district in north. Every part of the ubiquitous coconut tree is effectively utilized in this region - the flesh of the coconut is eaten, its fiber spun into coir, graded and used for a huge variety of uses or burnt for fuel; the stem turned into tables, chairs, banisters, vases, incense stick holders; the husk into figures of monkeys and Buddha heads; the shell with its natural concave shape converted into a enormous number of items that include paperweights, lidded containers with brass handles, cups, bowls, ladles, spoons, snuff boxes, sugar basins, powder boxes, trays with compartments, soap dishes, hookahs etc. The tools used are the Patiyaram the steel saw and a variety of chisels. The process followed is relatively simple though skill and a sure hand are necessary. First the outer surface of the hard coconut shell is smoothened with steel wool while the inner is smoothened with the aid of small chisels and the resultant surface is sandpapered. The separate pieces to make the final product are attached with screws. The first coat of polish is boot polish, after which a final coat of French polish is given. Craftspeople ingeniously make shapes by maximizing the natural curvature of the material. Koyilandi in the district of Kozhikode is renowned for its brass bordered coconut shell hookah these were made for the Arabs who had commercial trade links with Malabar Coast with the trend continuing till today, with most of the coconut shell products being produced for export. Other production centers are in Alappuzha; VaikomIrumbuzhikara in Koftayam district; Cherai in Ernakulam district; Koyilandi and Kozhikode and Thiruvananthapuram, Attungal and Neyyattinkara Thiruvananthapuram district. The ubiquitous use of coir in Kerala which is crafted into coir yarn, mats of all varities from simple to colored, embellished, inlaid to handwoven coir rope mats, mottled mats of yarn and compressed fiber mats to matting, rugs and carpets. In addition to organic, green, natural - a complete eco friendly material, coir is also exceptionally durable, being mothproof and resistant to fungi; additionally it is flame-retardant and anti static. Given its sterling natural qualities graded coir yarn is additionally used for different purposes such as the stuffing of couches and pillows, making cordage including large sized cables, saddles, brushes, fishing nets, upholstery, hats and finally, the manufacture of rubberized coil, a blend of coir and latex, which is used to pad mattress and cushioning. The coir craft can be largely seen in Chertala in Alappuzha district. Using tools that include air compressors, smoking chambers, hardboard moulds, gluing machine, traditional spinning wheels/raft, dyes, corridor mat press steel rods and weights the coir is treated and crafted into products. First the coconut husk is retted in the lagoons for between six to ten months. The softened husk is then beaten with wooden mallets and spun into coir yarn on the spinning wheel. The coir yarn is then woven into floor coverings either by handloom or by powerloom with colored coir yarn creating the patterns. During the finishing stage, the surface of the mats are sheared and then manually cut using clipping scissors. As in other weaving processes designs and patterns are also created through post weaving embellishment techniques such as hand beveling where the craftsmen manually trims the pile to define raised forms and stenciling. The edges of the coir mats are hand knotted; the craftsmen wears a home made rubber gloves for protection and support while pulling and pushing the thick needle through the tightly woven coir mat. Gandhi ji's three Monkeys who 'See No Evil, Speak no Evil and Hear no Evil' have found many forms and in Tiruvanathapuram they find form in coconuts. Each carved from a single un-joined coconut these sculptures are a rather incredible artistic feat. And they've got a shelf life of over a hundred years as coconut is an extremely resilient organic material, resistant to damage by termites and other insects.

After the initial carving of the surface is completed it is left in sun till its colour turns to a typical monkey brown. Then the edible portion of the coconut is removed. The hardest task is shaping the face as it need careful attention to give the monkey the desired expression. Though seemingly simple, there is great skill and attention required to carve the monkey to the right measurements because if the proportions get distorted the coconut must be discarded. There is no scope for rectification.

The entire process is done with a chisel, mallet, sickle and foreign cutting blades. The tools are prepared to the craftsman's own fashion & design. Sandpaper is used for the final touch. Ears and eyes and the foot are made from coconut nut shell. It is the hard wall protecting the edible portion which is tough to cut the determines the size of the monkey.

Manipur's coiled pottery is singular not only because the items are made without using a wheel or moulds, but also because Manipur is perhaps the only state in India where pottery is regarded as a woman's craft - the skill of making clay pots is said to be a divine gift bestowed on the women by their Goddess, Panthoibi. In Manipur, tribal Hindu women are traditionally considered to be 'potters', and are to be found in large numbers. Less than five per cent of the potters are men. The fact that basic forms are created without a wheel often permits greater flexibility and diversity in the forms worked out by the potters; equally, the burnished black surface, its starkness relieved only by carefully controlled detailing, is nothing short of stunning. The pottery includes clay objects, chiefly utilitarian pots, used for storing water, liquor and grain, as well as for cooking. Other objects like the hookah or dolls and toys are also made. The husband of Neelamani Devi, a national award winner, says that the first pot was made 1,400 years: the first clay object was a small mug which the king used for bathing. Mugs like that are still made today and used for drinking purposes, establishing a continuity that spans a millennium and a half of tradition, technique and artisanal activity.

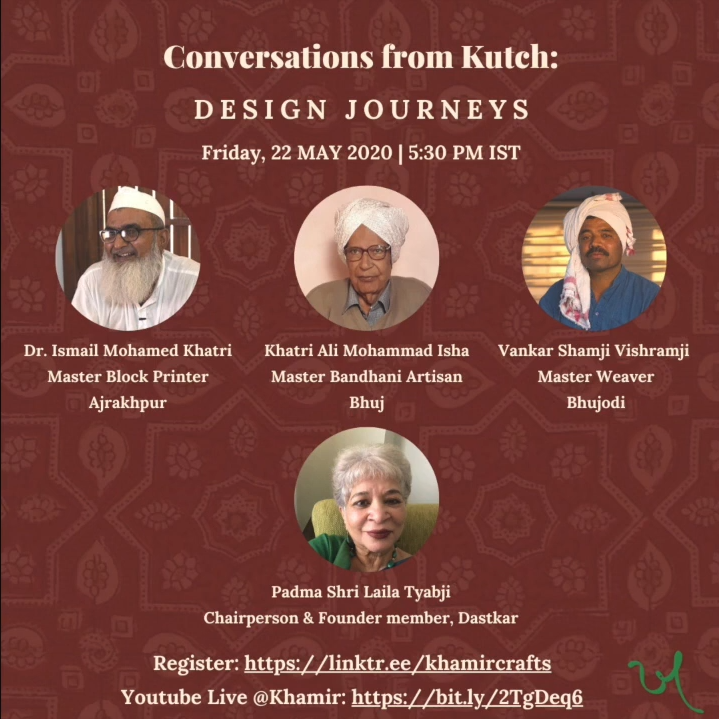

The dyeing and printing of fabric has been practiced on the Indian sub-continent since ancient times. Originally centred on Sind, part of Pakistan since Partition in 1947, the province is referred to as suvasa (‘the maker of good cloth’) in the Rig-Veda Samitha, written in the second millennium BC. The Romans were familiar with the Sindi cloths and, in the first century AD, cloth imported from the East was known as cendatus, or ‘Sindi cloth’. The earliest surviving examples of patterned cottons from the sub-continent were retrieved from Fostat, the harbour of Old Cairo. The provenance of the ‘Fostat’ textiles is Gujarat and they have recently been carbon dated to 1275 m (z75). Sind, Gujarat and neighboring Rajasthan, are centres for printing and dyeing cloth to this day. The business is dominated by the Khatri caste, who are predominantly Muslims in Sind and Gujarat, and Hindus in Rajasthan, One of the areas with the greatest, concentration of Khatri dyers and printers, is the desert region of Kachchh District in Gujarat.

THE KHATRIS OF KUTCH

The Khatris of Kachchh are renowned for block-printing and tie-dyeing, locally known as bandhani. They originally came from ‘Sind at the behest of the Maharao, the ruler of the District. One of the most prominent members of the Khatri community is National Crafts Award winner, Mohammad Siddik of Dhamadka village in E. Kachcbh, who tells the story thus:

‘In Sind we were Hindus. At the invitation of the King of Kachchh, Rao Bharmalji (1586-1632), we moved to this village [Dhamadka] 300 years ago. We selected this village because it had a live river: we needed the water to wash the cloth. The King gave us all the facilities and he didn’t take any taxes. If there were problems with selling, he helped us and also gave us pee land to stay in Kachchh. After three generations in Kachchh, we converted to Islam under the influence of a Muslim saint [possibly the Sufi, Shah Murad of Bokhara]: this was at the time of Maharao Rayadhanji (1666-1698).’

TRADITIONAL TRADE

Under the auspices of the Rao, a regular trade was established with the maldharis (pastoralists) of Kachchh: Muslim clans such as Mutwa, Jat and Node, who are herders of cattle and buffaloes in the Banni region of N. Kachchh; and Hindu shepherds and camel-breeders like the Rabaris. One of the cloths for which the Khatris became famous is ajrakh, printed on both sides and coloured with indigo and madder. The name is derived from azrak meaning ‘blue’ in Arabic and Persian. Considered an essential item of cultural identity by the Muslim maldharis, they wear it as a turban or as a lunghi, like a sarong: ‘Before electricity, if you got dressed in the dark, you might put your lunghi on the wrong way round and make people laugh.’

Dyed and printed with vegetable and mineral colours, the properties of the cloth exceed the merely aesthetic, as Ismail, Mohammad Siddik’s son, explains ‘the colours of the ajrakh are such that in the heat they are cooling and in the cold, warming. That’s why they are popular in the desert.’

Similarly, the Rabaris value their rumal (turbans) which were originally tie-dyed but latterly have been replaced by a cloth that is block-printed to look like tie-dye.

In the past Khatri families would practice both block-printing and tie-dyeing but as markets have developed and changed, practitioners have specialised in one or the other skill. This distinction has occurred within living memory. Mohammad Siddik, who won his National Crafts Award for block-printing and vegetable dyeing, describes the relentless tying of his early career: ‘I didn’t have anything. At that time the maximum you could make was six rupees for 1000 kadi (equivalent to 4000 dots as the fabric is tied folded in four) per day. I used to tie those things day and night but could only manage 500 kadi, three rupees worth of work. It was difficult to do 4000 dots in a day. ’

His business started to take off with Rabaris, as his son Ismail explains: ‘He was poor and had no money to do blocks and block-printing of ajrakhs for the Banni people. He knew how to do it but just couldn’t afford to. For the Rabaris all he needed was two ceramic pots, he made plain red cloth, he just used to do this colour work and sell it. For ajrakh or printed cloth, he needed at least four blocks which were 150 rupees each then. During the month [of Janmashtami], he made money from the Rabaris and slowly, slowly, he used to make the blocks at night. Once the Rabari season was over, he would prepare ajrakh and other maldhari cloths, take them to Banni and sell them. He has walked all over Banni.’

New markets While royal patronage and good natural resources launched the craft of block-printing and vegetable dyeing in Dhamadka, it has been sustained by certain resilience on the part of the Khatris. They have also had the foresight to respond to new opportunities and develop these as old markets dwindle. Mohammad Siddik and his family have been particularly active in resurrecting -the practice of vegetable dyeing as interest, especially from overseas, has grown. Natural dyes are now used in tandem with aniline dyes: ‘In the past we made only vegetable colours but in 1950 synthetic colours came. Our production became faster and the colours were very good, so our customers accepted them immediately, and those colours are still going today … In 1975, we started vegetable colours again which the foreign customers preferred. In 1973, the government of Gujarat started Gurjari [state handicrafts emporium] and with the help of some designers from the National Institute of Design, they developed designs with Dhamadka. This proved very successful. Today 75% of our production is sold in foreign markets. ’

Innovations Overseas business has been a catalyst in revitalising a traditional practice. Ismail identifies the transformation of old designs into new products for the export market as an important factor in the success of his family’s business: ‘The patterns traditionally associated with these peoples have been re-adapted and mired together to make new designs for bedcovers, sheets and dress materials. ’

Awareness has grown of the need for quality control and this has prompted a number of innovations in the process of applying colour to fabric, although the constituents remain unchanged: ‘We have to use new ideas, quality is important for the foreign market. For example in the past, boiled pomegranate was wiped on the cloth and the colour was uneven. This was not considered a problem as the piece was multi-coloured and the locals accepted it. This kind of unevenness would not be accepted by foreigners, so the cloth is-placed on the sand and the colour is sprayed on.’

The natural resource that made Ismail’s forebears select Dhamadka, the river, has now dried-up. The rapid descent of the water table in Kachchh has alarmed craftspeople, pastoralists, and farmers alike. To overcome this problem for the time being, the family has sunk a well and installed an electric pump at their farm, a kilometre outside the village proper. Here they can still wash the cloths in flowing water, as tradition demands.

A secure future Ismail and his brothers, Razzak and Jabbal, are the ninth generation of Khatris in Dhamadka. They al1 work in the family business and are now instructing their own sons in the art of block-printing and dyeing. Outside of the sphere of Kachchh, there is a growing demand at national and international level, for these master dyers to demonstrate their skills. Modest of the family’s international acclaim, Ismail attributes their continued success to faith in God: ‘I am making cloth, people are wearing it and it makes them happy, brings them joy. If everyone had this philosophy, then everyone would be shanti (‘at peace’). In the world, god makes a border: inside that border everyone is happy, working and eating halal (‘pure’); outside that border, all is loss and sorrow. When a man is eating halal, his mind works well… if he is eating haram (‘impure’) then he is like a beggar, begging for food at everyone’s house and with no intention of doing an honest day’s business.’

First Published: Textiles Magazine, Issue 2, 1998These numbers should suffice to give policy makers a moment of pause - 135 lakh people, 70%, 6, 38,365 villages, 1000 clusters, 5000 years. In order they are, the hugh base of craftsperson’s and weavers, trained in skills that are learned outside the mainstream of the current educational system; over 70% of whom belong to the socially and economically deprived sections of our society; self employed and working across lakhs of villages, the second largest sector after agriculture in terms of employment; With over 1000 handloom and handicraft production centres spread throughout India; the sectors civilizational links that go back 5 millennia to ancient multi- cultural traditions and its continuing contemporary contribution not only as the wellspring of Indian creativity, but equally to rural economic development.

Yet in reports, statements, conversations on policy and development this sector is notable for its absence. It is time now to come out of the shadow to build a path to development, equity and growth for this sector.

The focus of this paper is on a particular thought - the pushing the frontiers of mainstream education to include the methodologies of creativity and technical hand-skills - mainstreaming the traditional knowledge systems of Indian craft, inculcating it into the curriculum, equitably combining the intellectual with the hand-skills.

The Indian craftsperson and weaver has till now belied all doomsday expectation, working persistently against difficult odds, combining entrepreneurial abilities, with technical virtuosity rooted in an in-depth understanding of materials and processes they continue to pursue their trade and create products that have marked our civilization and continue to do so till today. Across villages, hamlets, tribal swathes and urban fringes, in the most unlikely places indigenous and ancient technologies are preserved, orally handed down till today.

The excavations at the Harrapan sites in the Indus Valley and at Mohenjodaro are evidence that the seeding of craft and weaving traditions had already developed root. This base then formed the blueprint of the start of a 5000 year journey that continues till today. Developing ways of thinking and seeing, distinguished by syncretism, marked by multi-cultural pluralism and oral instruction, craftspersons have managed to preserve traditions while continuously absorbing and assimilating new systems, ideas and trends. Over the millennia waves of migrating peoples, successions of rulers and empires; explorers and merchants, traders and priests moulded the craftsperson’s vision and helped define their enormous vocabulary of form, material and design, echoing and amalgamating ideas, customs and cultures. Further with the development of trade routes both maritime and over-land influencing the development of skills and creation of product offerings, styles and colours the Indian craftsperson manufactured products for a spectrum of consumers - from those located close to home as well as extending far flung to markets across the world.

Crafts1 and craftspersons2 across India today, continue this journey.

Their oral knowledge systems extend across a wide continuum of learning - from the extremely complex with an understanding of the principles of mathematics, physics, chemistry and engineering to those that are based on usage and observation of the surrounding eco-system and ecology, all centred around the fundamental principles of community knowledge systems developed over generations of study and practice. From the building of ocean going ships in Beypore in Kerala to the casting of the largest metal cauldrons in the world, from the making of paper frf theom waste cotton in Jaipur and Pondicherry to the creation of dyes, colours and pigments from vegetaf theble and organic material, from enamelling metal in Varanasi to the fusing of metal on to glass in Pratapgarh, the precise tying and dyeing of yarn and its subsequent calligraphic weaving of on the loom in Orissa to the making of metal yarns for embroidery in Lucknow are only a few examples as the variety of techniques and processes is enormous.

The craftsperson’s mastery over their tools, using them in creative, inspired ways to change raw materials into three dimensional products. Tools usually locally produced, useing eco-friendly raw materials with a low wastage content, employing indigenous technological processes that include, to mention a few, smelting, weaving, beating, shaping, moulding, tempering, turning, varnishing, lacquering, twisting, welding, throwing forging, binding, dyeing, casting, tying, staining, soldering, embellishing, filigreeing, knotting, spinning, carving, plaiting, sculpting, painting etc. Working with a profound knowledge of these processes on materials as diverse as metal, wood, clay, stone, lac, wax, paper, glass, a range of grasses and fibres, bone and shell, leather, and textiles, each with enormous regional and individual variations within every group of specialization. The exhaustive understanding of material is based on usage and context, influenced by geography, historic traditions and cultural influences that are approached through a multitude of methodologies and processes.

Skills and techniques, craft ritual and folklore are handed down through oral instruction and rigorous on-the job training, within and across generations. Taught through alternate knowledge transmission systems that do not form part of mainstream educational systems prevalent today, with no brick and mortar buildings, no text books or ink these specialized crafts and handlooms are hereditary specialties passed on from generation to generation within communities and families. The women of the Lambani community who embroider and quilt, the Prajapati community of Molela who mould clay plaques, the Moosaris of Kerala who cast the bell metal Charakku cooking utensils in diameters of up to 8 feet, the Patola yarn resist saris woven by members of the Salvi family in Patan characterised by mathematical precision in the multiple tying, dying and weaving, the Sthapatis of Swamimalia who cast the bronze idols, the Paneka community who weave the Pata sari, the Meghwals who turn wood and decorate it with lac are only some such examples.

Mainly located in rural3 areas, the craft sector provides employment to many millions4 of people, an overwhelming majority of whom belong to the weaker, more vulnerable sections of society, being either Scheduled caste or tribe or belonging to minorities or to other backward classes. Craft production is widely dispersed across the length and breadth of the country, with the parallel coexistence of isolated individual family units, craft clusters, home/cottage industries, and small-scale and medium-scale enterprises. From rural hamlets outside the city of Banaras where brocade weaving is a home based activity involving family members to Bagh in Madhya Pradesh where the iconic block prints are produced in karkhanas with over a hundred persons employed, the lace makers of located in clusters in Warangal, the Kauna Phak reed mats weavers in the East district of Imphal to the painters of glass in Thanjavur, the carved and painted wood work of Gangtok, the tribal weavers of the Kotpad textile in Koraput, the community of Patachitra painters of Puri to Pethapur on the outskirts of Ahmedabad where seven families continue to treat the wood and carve the intricate blocks that form the basis of the hand block printed textile trade.

The continuing encounters of the traditional crafts with the demands of modern, urban living have resulted in a juxtaposition of ancient technologies that are catering to a globalised world. These immense numbers of self-employed, self-organised, skilled craftspersons are the bearers of India’s traditional knowledge, the source of our creativity and keepers of our national cultural identity.

Over the last few decades shifting dynamics have led to an erosion of livelihoods in the craft sector. The crisis in crafts has been ascribed to many reasons, not least being the disappearance of traditional markets with a dramatic shift in consumer choice from hand-crafted, woven goods to factory-made products. The customer base has shifted, with rural consumers accessing mill made products and high end urban customers being wooed by branded products. The economies of scale inherent to the factory sector result in the mass production of goods of uniform quality at prices unmatchable by craft people. Simultaneously, the availability of replicated and fake craft products that are marketed as handcrafted, hand-woven and traditional at far lower prices than the original has hit crafts people hard.

Industrialisation has changed forever the social systems that controlled caste and community linkages to specific occupations. Likewise, globalization and urbanisation has made alternative career options accessible. With an educational system de-linked from traditional knowledge systems this sector has experienced a systematic dwindling of its skills and accomplishments and a devaluation of their learning that constituted the repositories of the craft knowledge systems.

Crafting of objects and their associated technologies are often determined by geographical location to raw material. Materials were a local resource with skills evolving gradually and being handed down by families and communities. Economic growth has broken the link between sources of raw material and local communities, for instance cotton is no longer processed and woven in the areas in which is grown as it was in the past.

Compounding the crisis is the lack of interest in the younger generation of craft families in continuing in craft practice due to perceived prejudices and inequalities of status. The underlying belief that information garnered from text books is superior to received oral knowledge has added to the problem.

Globalization has brought in new influences and technologies, and increasingly rapid social transformations, the familial system of apprenticeship faces cracks and fissures without a suitable replacement in place. Urgent thought needs to be given to alternative formats for learning and training as we face a future of surging urban migration, issues of deskilling and unemployment.

To meet the challenges of the 21st century any developmental initiative while seeking meaningful formats to work in will have to grapple with these baseline issues and a sustainable growth trajectory cannot be isolated from this larger context.

It is hardly surprising that there are any number of debates around the appropriate path to development, equity and sustainability. This paper presents for discussion a particular focus – the deconstruction, codification and mainstreaming of the multi-dimensional oral traditional knowledge systems of craft practice into mainstream education, as an underlying premise for creating an enabling environment for the craft sector in India.

What is critical at this point is to explore the issues that confront the process as it exists right now, and to evolve methods of thinking and ideating that make the process viable and meaningful.

This knowledge based intervention though poised as a value-added and productive process is distinctly complicated by the fact that most craftsperson’s and weavers are located outside the ambit of conventional notions of what constitutes mainstream education – this disassociation has been inimical to all. The question arises as to where does one go from this point to a future where this creative, productive and high rural employment domain be brought equitably into the mainstream, by creating an even handedness between these repositories of creativity and the mainstream

It is time to remedy the relative neglect of this aspect at a time when – despite the value of crafts being recognised world-wide –innumerable factors continue to endanger their very experience.

The comtemperorary relevance of this focus is for five distinct reasons

First. At the outset, it is well-documented and proven that free and open access to information creates an environment that empowers individuals and societies; it is an instrument of constructive change a catalyst for introducing systematic and significant windows of opportunity. This could un-cage a sector where the range of learning and oral instruction covers areas as diverse as Thanka painting to Warli art, from the metal casting of temple gods to the creation of Dhokra work, from mask making to hand spinning, wood and stone carving, papier mache to glass blowing, the list is endless, all these practitioners would benefit from inclusion in the mainstream of knowledge as would the rest, equally if not in greater measure.

Second, an accessible framework of institutions, training and research material is a necessary prerequisite for growth. For this knowledge to be effectively used it needs to be understood in all its forms and to be presented in a manner that is relevant to student. It must stimulate ideas and allow for new creative connections to be made. Connections that could provoke innovation and innovative uses of these Indigenous technologies that demonstrated inspired ways of morphing materials into products. The tools used in conjunction with these technologies, all locally manufactured, need to be reassessed and re-evaluated and for the knowledge to be effectively used both in the laboratory, as a teaching instrument and in a manner that is relevant to its appropriate use; for this we need additionally to develop programs to upgrade and improve the tools.

The availability of an infrastructure of this kind works an effective mechanism for development, essentially as a means of removing bottlenecks to growth. Given the scale and potential of the sector, the absence of systematic training curriculum’s, and institutions that research, and provide the training, have been a major lacunae across the board and a considerable factor in why the sector has not taken its rightful place considering its considerable contribution to the economy in terms of employment but also its immense cultural significance.

A third reason for this approach is that at a time when the rest of India is going through a phase of resurgence facilitated by the growth of the general economy, the effects of economic reform and benefits of the rapid spread of information technology all these have largely bypassed the craftsperson, creating a new form of deprivation and impoverishment for those with no access. Although techniques and skills are abundant they need to be understood in all their forms. Craftsperson’s themselves often remain isolated owing to their inability to access information and training. While we have this vast skill pool on the one hand, the flip side of the coin is the glaring lack of formal mainstream training and educational institutions available to nurture and grow these skills while simultaneously building a cadre of young professionals. This fissure in the system thus curtails the ability of craft communities to respond effectively within the contemporary matrix, in effect crippling those who suffer from the twin drawback of information deprivation and poor outreach.

Fourth. There is an urgent need to research, analyse, categorise, and document craft traditions and developments as there is a very real danger of technologies and processes, motifs, designs and traditions dying out due to change, under use, or even the death of a specialised artisan or craft family/group. Moulding, shaping, weaving, forging, shaping are only some of the processes that India’s craftspersons have mastery over. Some seemingly simple yet classic, forming the backbone of technology to the interconnected and complex. Across the globe when we examine the seed source of modern manufacturing and technology you see the hands of a craftsperson – using the springboard of ancient technologies adapting and transforming them in innovative ways.The fact that many craft traditions are oral makes research and codification even more critical. In its absence of any documentation, oral traditions, once lost, can never be revived. It is a permanent loss. This cannot be overemphasised.

The fifth reason for the use of knowledge-based interventions is that India’s education system has been touted as one of the critical factors in its economic rise. Juxtaposed alongside is the passing of the momentous Right to Education Bill in Parliament in 2009. With 50% of India’s population below the age of 25 and the projection that by 2020 the average age in India will be 29 it is critical that the system be prepared to meet the hugh demand for education. It is time now to inculcate craft know-how and training into the curricula with an equal emphasis on the intellectual, cerebral, the technical and the hand skills. To take a leaf from other countries – Japan supports rigorous training in over 200 traditional crafts; France has a Master Of Arts, Sweden runs National Folk craft institutions while Korea invest heavily in training the next generation. The United Kingdom incorporated the arts and crafts movement into the mainstream curriculum in the mid 19th Century to further power their Industrial Revolution.

Though craft has moved ahead, not static or fossilised in time, all those who work in the area are aware that though change is constant its sheer speed and rapidity is resulting in fragmentation and disorientation of these long established synergies.

The challenge ahead lies in designing frameworks that are sensitive to the sheer complexity of the sector. What is critical at this juncture is to explore the process and to evolve methodologies that contribute to making it a significant exercise.

It would be necessary to start with a baseline documenting of community knowledge, traditionally transmitted orally, studying the process, its workings and its most notable features and then placing it in its mainstream curriculum context. Collating the information on the raw materials and their processing, colours and motifs used the ritual or symbolic significance, techniques employed, values ascribed, the associated norms, perceptions and beliefs are some of these. Presenting not only the skills and techniques involved but the specific meanings of the form of expression, meanings derived from the local context in which the craftspersons operate and the purpose for which they produce. By analysing the pros and cons and key features with its qualities and characteristics including degrees of process accuracy we take the first steps in building and amalgamating its scientific principles. A small step in this direction has already been taken by the Craft Revival Trust to create an accessible knowledge infrastructure for the crafts. Making information available on craftspersons and on a wide variety of craft subjects. The process involves all the constituents while rooting the work in a development framework with the craftsperson at the centre of the exercise.

The next step would be to build a theoretical framework that ‘legitimises’ and amalgamates the principles and concepts of oral, and local community knowledge of these eco-technologies of craft practice within the commonly accepted scientific and technological infrastructure. In effect researching the science that underlies the craftsperson’s arts. This knowledge, an intrinsic part of craft practice developed over the ages has responded and evolved to changing ecologies and environs. For instance the understanding of plant material by craftsperson’s to weave baskets, thatch homes, make furniture, build bridges, make music, create colour and a myriad other uses is only one such example. We need to apply scientific rigour to the study of processing of materials and techniques of craft production whether it be plant or metal, leather or clay, stone or wood by uncovering and studying the underlying principles at the heart of the technicalities of craft. Studying the parameters, creating benchmarks and applications, retaining the creative, while removing the subjective approach through a process of standardisation. This collaboration among scientists, technologists and the bearers of oral craft knowledge through application of stringent scientific principles to traditional hereditary knowledge to document concepts, principles, applications and practices could lead to a uniquely Indian knowledge system, creating networks and linkages both within and outside the sector giving India a global edge.

Concurrently we need the introduction of craft technology study in the curricula of schools and colleges, recognising that the current lack of awareness is a form of deprivation for everyone of us. Re-recognizing indigenous technologies is a vital part of this process. This need has become even more immediate with the passing by Parliament in July 2009 of the Right to Education bill and the push to universalise access to education at the secondary level.

Simultaneously, there has to be a move towards greater equity, a removal of barriers within academia and scientific and technological laboratories, which are weighted against the bearers of traditional craft knowledge for a more equitable, even-handed inclusive education. Moving beyond tokenism to create substantive change through institutional development, formation of indigenous technology laboratories, the endowment of Chairs in Universities to bearers of traditional knowledge to the awarding of honorary doctorates, as for instance in 2003 De’MontFort University, Leicester, UK recognised the master Ajrak hand block printer and natural dye revivalist, Ismail Khatri by awarding him an Honorary Doctorate. Thereby creating a movement and an environment that stimulates ideas that allow for new creative constructs to be built and make connections that could provoke the use of appropriate technologies in manufacturing.

With steady economic development and a 9% rate of growth has come increased prosperity, but we as a nation cannot forge ahead unless we push the boundaries of education policy in an equitable and inclusive way. It will require a concerted and sustained effort to ensure that this essential part of our cultural fabric and these keepers of our traditional knowledge are nurtured and take their rightful place for the next millennia.

The future depends on how we tackle this massive skilled human resource whether we build to our advantage or let it all be frittered away.

|